Novel molecular-targeted agents have recently been approved. This review summarizes and assesses the effects of molecular agents in metastatic colorectal cancer based on the available phase II and III trials, pooled analyses, and meta-analyses/systematic reviews. The future challenge will be a better selection of the population that will benefit the most from specific anti-vascular endothelial growth factor or anti- epidermal growth factor receptor treatment and a careful consideration of therapy sequence.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Bevacizumab, Cetuximab, Panitumumab, Aflibercept, Regorafenib

Abstract

Background.

Survival of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) has been significantly improved with the introduction of the monoclonal antibodies targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Novel molecular-targeted agents such as aflibercept and regorafenib have recently been approved. The aim of this review is to summarize and assess the effects of molecular agents in mCRC based on the available phase II and III trials, pooled analyses, and meta-analyses/systematic reviews.

Methods.

A systematic literature search was conducted using the meta-database of the German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information. Criteria of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network were used to assess the quality of the controlled trials and systematic reviews/meta-analyses.

Results.

Of the 806 retrieved records, 40 publications were included. For bevacizumab, efficacy in combination with fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy in first- and subsequent-line settings has been shown. The benefit of continued VEGF targeting has also been demonstrated with aflibercept and regorafenib. Cetuximab is effective with fluoropyrimidine, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) in first-line settings and as a single agent in last-line settings. Efficacy for panitumumab has been shown with oxaliplatin with fluoropyrimidine in first-line settings, with FOLFIRI in second-line settings, and as monotherapy in last-line settings. Treatment of anti-EGFR antibodies is restricted to patients with tumors that do not harbor mutations in Kirsten rat sarcoma and in neuroblastoma RAS.

Conclusion.

Among various therapeutic options, the future challenge will be a better selection of the population that will benefit the most from specific anti-VEGF or anti- EGFR treatment and a careful consideration of therapy sequence.

Implications for Practice:

Introduction of targeted agents in treatment algorithms of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) has significantly improved median overall survival. Emerging therapeutic options are available for patients with mCRC in 2014. This article reviews and assesses the available phase II and III data in order to elucidate the best combination and sequence modalities of targeted therapies in patients with mCRC.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers and the second leading cause of cancer worldwide [1]. Approximately 25% of newly diagnosed patients have already developed metastases, and 50% of all CRC patients will develop metastases over time as the disease progresses [2]. Systemic therapy was restricted to fluoropyrimidine (5-FU)-based regimens alone or in combination with oxaliplatin or irinotecan for many years [3, 4].

Development and introduction of monoclonal antibodies targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in treatment algorithms have significantly improved median overall survival (OS) of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer [5]. Bevacizumab is a recombinant humanized antibody against VEGF that improves survival in first- and second-line therapy [6, 7]. Cetuximab and panitumumab are two monoclonal antibodies that target and bind the extracellular domain of the EGFR, thereby inhibiting its dimerization and activation. Both improve the outcome of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) either as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy [8–11]. In contrast to bevacizumab, cetuximab and panitumumab are only efficient in a subset of patients whose tumors are wild-type (WT) for Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS) and neuroblastoma rat sarcoma (NRAS) [12–14].

Recently, the recombinant fusion protein aflibercept has been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for combination therapy with 5-FU, leucovorin (LV), and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) after failure of oxaliplatin-based treatment [15]. Moreover, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the multityrosine kinase inhibitor regorafenib for the treatment of patients with mCRC in late 2012, followed by the EMA in August 2013. Because of this development and current wide application of molecular agents, the OS of patients with mCRC has increased to more than 30 months in recent phase II and III clinical trials.

In this review, we summarize the efficacy of the currently approved targeted therapies bevacizumab, cetuximab, panitumumab, aflibercept, and regorafenib in mCRC. Based on the available phase II and phase III trials, as well as meta-analyses and systematic reviews, we will assess and elucidate their eligibility in clinical practice.

Methods

Identification of Publications

A systematic literature search in AMED, BIOSIS Previews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, DAHTA-Database, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, EMBASE, EMBASE Alert, Health Technology Assessment Database, MEDLINE, NHS Economic Evaluation Database, SciSearch, and SOMED database was done using the meta-database of the German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information. Manual search was additionally performed to keep the review up to date. The full-text search included works published in English and German during 2000–2014. The following German and English search terms were used and finally combined with AND: (a) (Darmkrebs OR Rektumkrebs OR mCRC OR CRC OR [{colorectal? OR kolorektal? OR colon OR kolon OR Rectum OR Bowel} AND {Cancer OR Carcinom? OR Karzinom OR Tumor OR Tumor OR Neoplasm?}]); (b) (stadium III OR stadium IV OR stadium 3 OR stadium 4 OR stage III OR stage Iv OR stage 3 OR stage 4 OR metasta? OR advanced); and (c) (cetuximab OR panitumumab OR bevacizumab OR Regorafenib OR Aflibercept). The question mark is used as a wild card to represent any number of characters. In addition, a hand search was conducted.

Titles and abstracts of all identified publications were reviewed independently by two researchers. Only full-text, randomized, controlled phase II and phase III original studies and their relevant pooled or updated analyses, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were included. Early publications concerning EGFR targeting with the so far unknown predictive quality of KRAS were excluded. Moreover, only studies randomizing patients into arms either with or without a targeted agent were included. Studies combining and/or comparing targeted agents were excluded. The eligibility of the studies for the review was also assessed independently. Data were collected for each included article across a range of elements, including, authors, journal, study question, population, intervention, setting, and perspective, among others.

Assessment of Publications

Checklists of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) were used to assess the quality of the controlled trials and systematic reviews/meta-analyses. The methodological assessment is based on 10 questions that focus on certain aspects of the study design that have been shown to have a significant influence on the validity of the results reported and conclusions drawn. For overall assessment of the controlled trials, 8 of 10 checkpoints for internal validity (from the checklist for controlled trials) were included. Points 1.8 and 1.10 were not taken into account because point 1.8 was to be answered as free text and was therefore not objectively comparable, and the information necessary to give an answer to point 1.10 was rarely available. For controlled trials, ++ was defined as “very well conducted,” indicating that 6–8 of 8 checkpoints were assessed as “well covered.” + was defined as “well conducted,” indicating that 3–5 checkpoints were “well covered,” and − was defined as “poorly conducted,” indicating that 0–2 checkpoints were “well covered.” For our overall assessment of the identified reviews and meta-analyses, we included all five checkpoints for internal validity from the checklist for reviews and meta-analyses. ++ indicated that 4 or 5 of 5 checkpoints were assessed as “well covered.” + indicated that 2 or 3 checkpoints were “well covered,” − was defined by 0 or 1 “well covered” checkpoints. The study quality of pooled analyses was not separately assessed as originated from the controlled trials.

Results

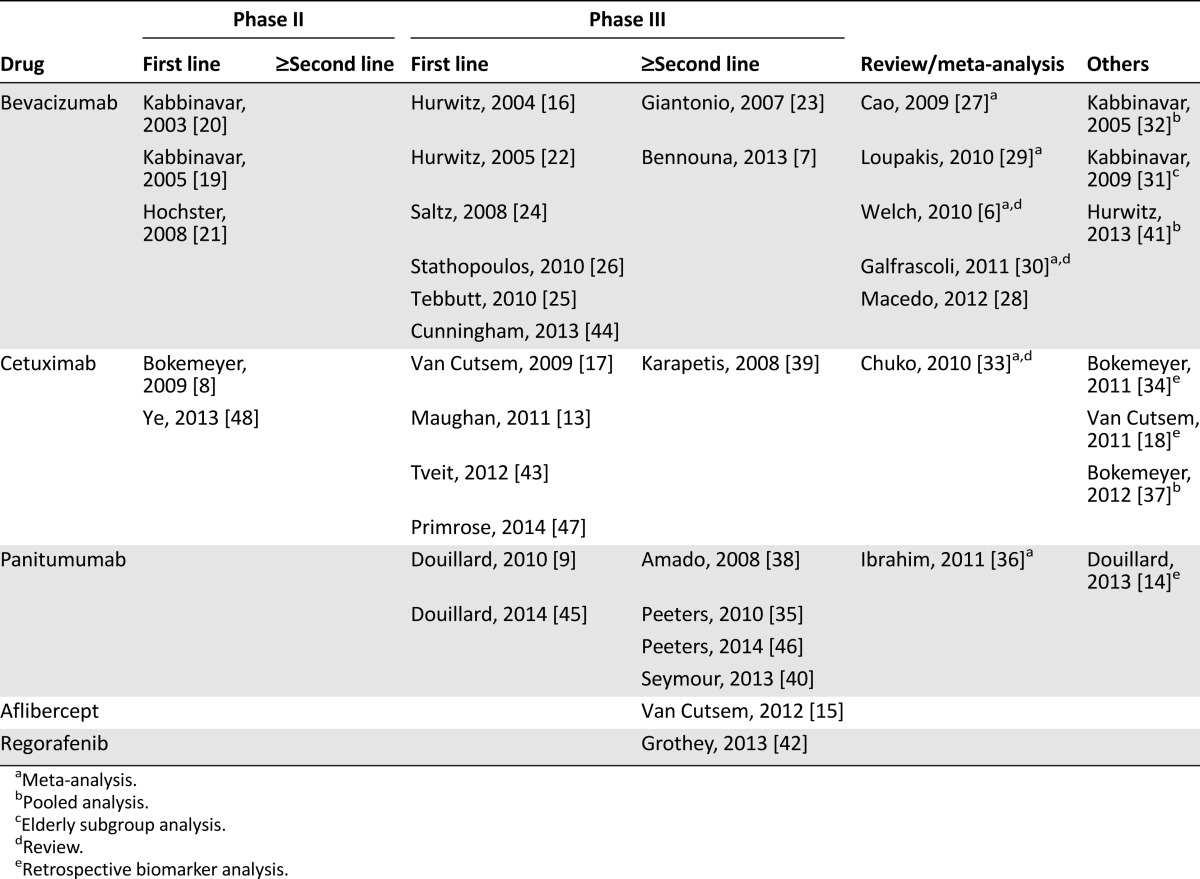

Altogether, 40 publications of the 806 retrieved records were included after selection [6–9, 13–48]. The selection consisted of 24 randomized controlled trials, 2 long-term survival analyses, 7 reviews/meta-analyses, and 7 pooled, updated, or subgroup analyses of the included randomized controlled trials. An overview of the identified publications is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the included full-text articles

Bevacizumab

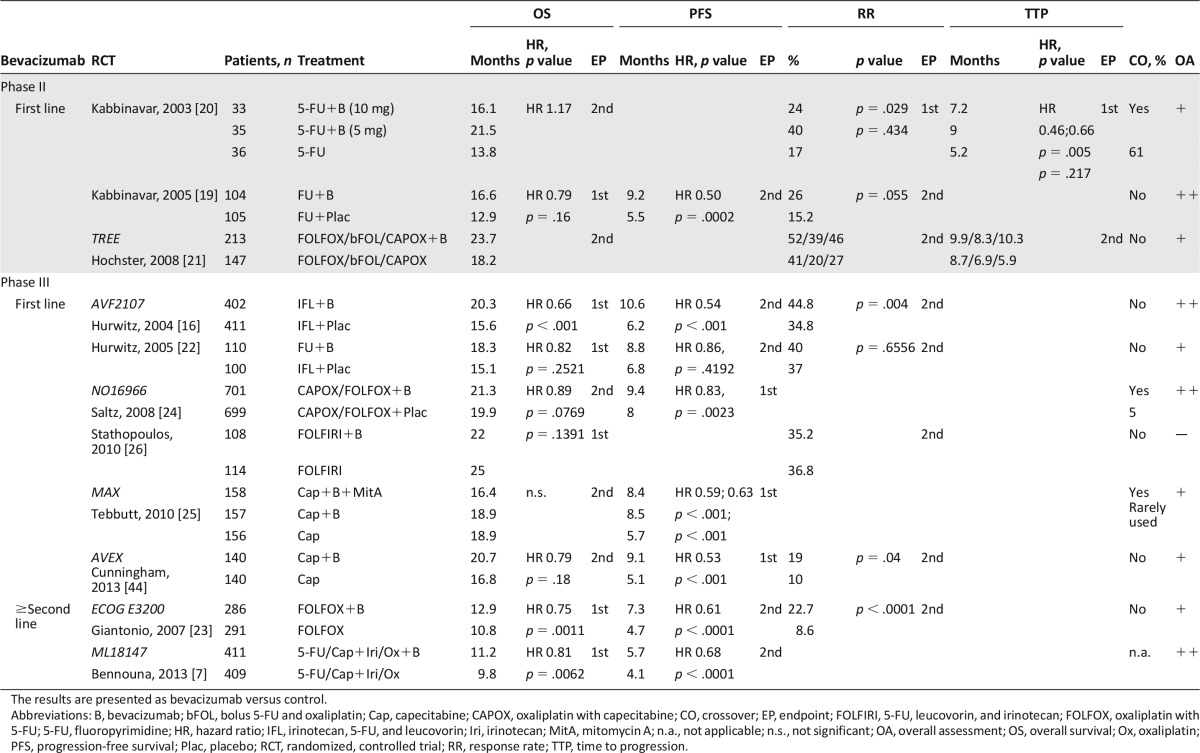

For bevacizumab, three phase II trials in first-line settings were analyzed. Kabbinavar et al. investigated bevacizumab in combination with 5-FU-based chemotherapy in two clinical trials. The first study reached its primary endpoint time to progression in contrast to the secondary endpoint OS. Best results were obtained with 5 mg of bevacizumab [20]. More than 60% of the patients from the control group received bevacizumab in subsequent therapy. The second phase II trial by Kabbinavar et al. [19] investigated 5 mg of bevacizumab in a larger patient population reaching a significant improvement of progression-free survival (PFS) and a trend for a better OS and median duration to response with bevacizumab. Three oxaliplatin-based regimens with or without bevacizumab were compared within the TREE study [21]. This study was focused on adverse events, which were not significantly modified by bevacizumab.

Among eight phase III trials evaluating bevacizumab in various treatment settings, significant improvements of major outcome parameters could be demonstrated. Hurwitz et al. [16] analyzed bevacizumab versus placebo in combination with irinotecan, 5-FU, and LV (IFL) as first-line therapy. In this study, the primary endpoint OS as well as the secondary endpoints PFS and response rate (RR) were significantly improved by bevacizumab. Analysis of the third cohort of the Hurwitz study, 5-FU/LV and bevacizumab, revealed that 5-FU/LV plus bevacizumab was at least as effective as the IFL regimen without bevacizumab [22]. This arm, however, was discontinued after the first interim analysis revealed an acceptable safety profile for the combination of IFL with bevacizumab. The NO16966 trial compared oxaliplatin with capecitabine (CAPOX) or oxaliplatin with 5-FU (FOLFOX) plus bevacizumab or placebo [24]. Bevacizumab significantly improved the primary endpoint PFS, whereas the secondary endpoint OS was nonsignificantly improved. Stathopoulos et al. [26] investigated bevacizumab in combination with FOLFIRI in a small, single center trial with only 222 patients. There was no statistical difference in the primary endpoint OS between the arms with a better trend for chemotherapy alone in this poorly conducted study, which did not provide important information such as dose intensity and treatment duration. Moreover, treatment was stopped after eight cycles of therapy until disease progression. The MAX study analyzed the effects of bevacizumab on capecitabine-based chemotherapy first-line setting in a three-arm design [25]. Bevacizumab significantly improved the primary endpoint PFS, whereas the secondary endpoint OS remained unchanged. Overall, more than 60% of the patients received subsequent therapies. Recently, the AVEX study provided evidence for a safe and efficient administration of capecitabine with bevacizumab in elderly patients. PFS and RR were significantly improved. In contrast, the OS benefit of 4 months did not reach statistical significance. However, the study with only 280 patients was not powered to detect differences in OS [44].

For second-line treatment, the three-arm phase III ECOG E3200 trial compared FOLFOX with and without bevacizumab in irinotecan-resistant patients [23]. The bevacizumab-alone arm of the study was closed to accrual after an interim analysis that suggested an inferior survival compared with the chemotherapy-containing arm. The addition of bevacizumab significantly improved all defined endpoints OS, PFS, and RR. Recently, the ML18147 trial provided evidence for a continuation of bevacizumab after progression in first-line therapy [7]. The four chemotherapy regimens FOLFOX, FOLFIRI, CAPOX, and capecitabine with irinotecan were evaluated with or without bevacizumab, whereas the choice between oxaliplatin-based or irinotecan-based second-line chemotherapy depended on the first-line regimen (switch of chemotherapy). Both OS and PFS were significantly improved.

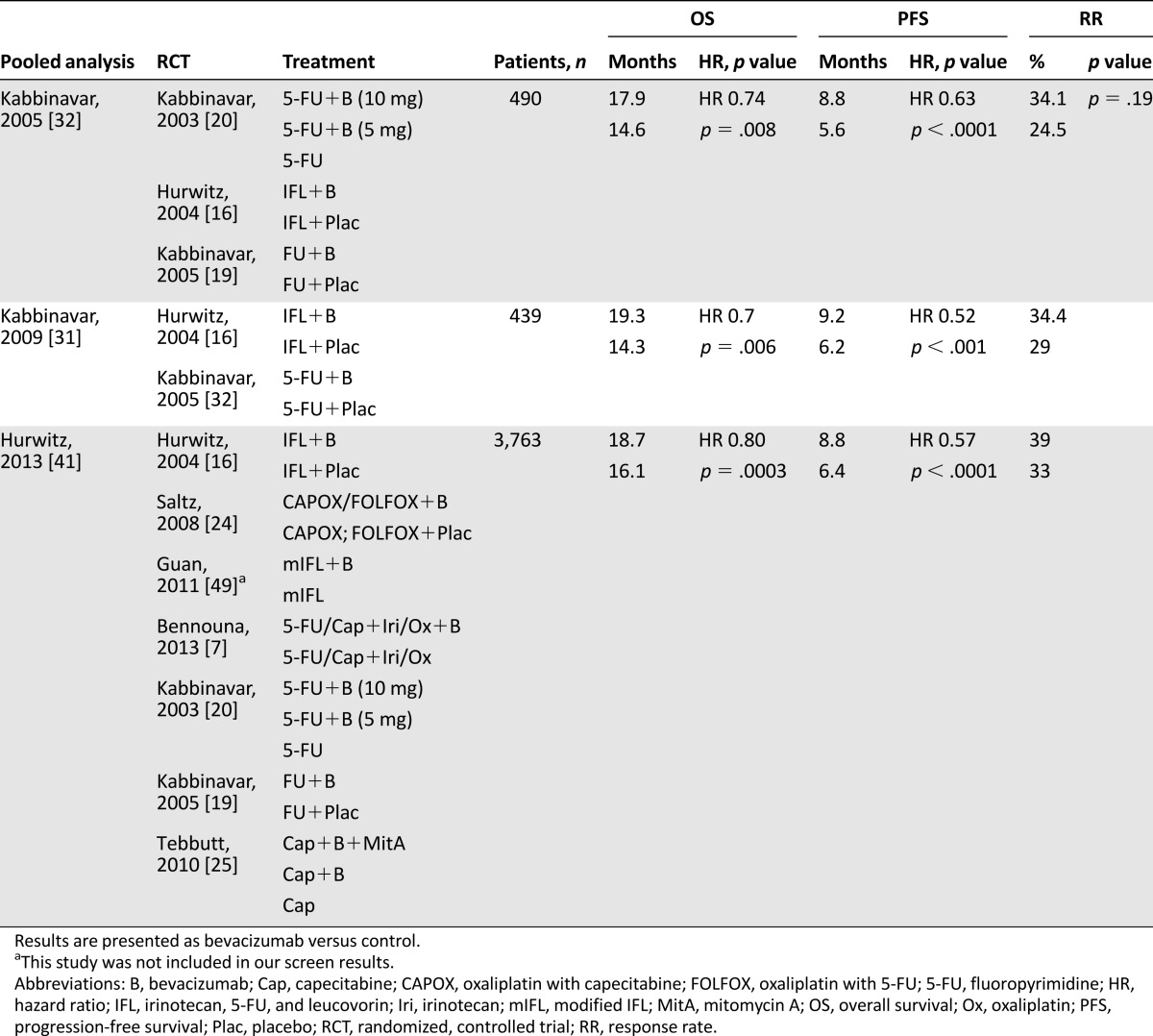

Three pooled analyses and five systemic reviews and meta-analyses were analyzed for bevacizumab. All analyses suggest a significant benefit of bevacizumab to any chemotherapy on OS and PFS [6, 27–32, 41]. The toxicity was modestly higher in the bevacizumab-containing arms. The most common adverse events (AEs) for bevacizumab were bleeding, hypertension, thromboembolic events, and proteinuria/albuminuria.

All trials but one and all reviews and meta-analyses for bevacizumab were assessed very well or well conducted by the SIGN checklist. The main contents and assessments of the trials pooled analyses, reviews, and meta-analyses are listed in Tables 2 and 3 and supplemental online Table 1.

Table 2.

Summary of the selected randomized, controlled trials, and according assessments by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network for bevacizumab

Table 3.

Summary of the selected pooled/subgroup analyses and according assessments by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network for bevacizumab

Aflibercept

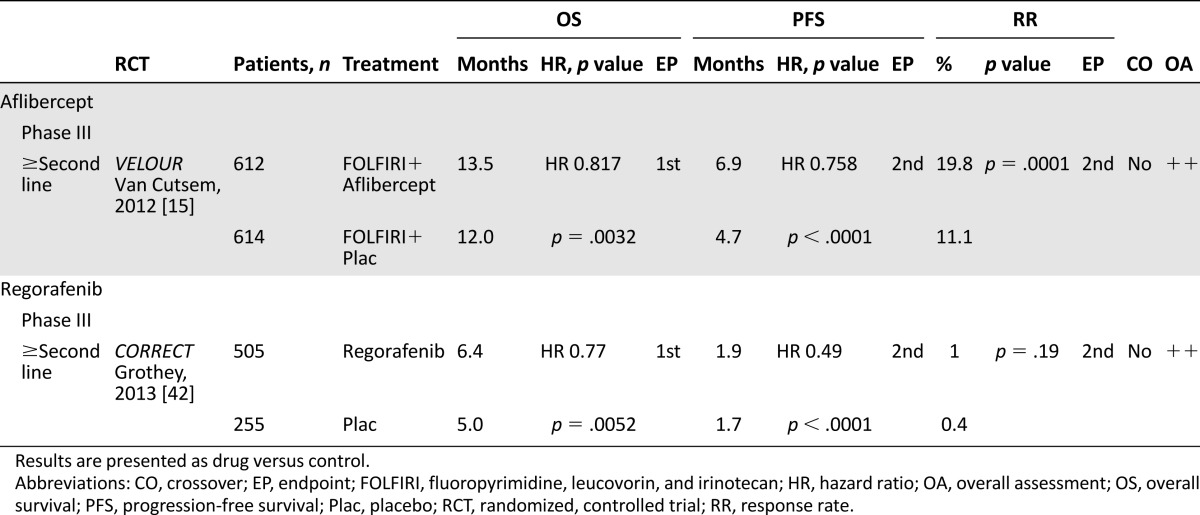

Aflibercept was assessed so far only in one phase III trial in patients with mCRC previously treated with oxaliplatin [15]. Aflibercept in combination with FOLFIRI conferred a statistically significant OS and PFS benefit over FOLFIRI combined with placebo. Adverse effects reported with aflibercept combined with FOLFIRI included the characteristic anti-VEGF effects, such as bleeding and hypertension, and also reflected an increased incidence of some chemotherapy-related toxicities.

The trial was assessed as very well conducted by the SIGN checklist. The main characteristics and assessment of the trial are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of the selected randomized, controlled trial, and according assessments by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network for aflibercept and regorafenib

Regorafenib

One phase III trial analyzed the multityrosine kinase inhibitor regorafenib as last-line therapy in patients with chemorefractory mCRC [42]. Regorafenib significantly improved the primary endpoint OS and the secondary endpoint PFS. Together with the VELOUR and ML18147 studies, the CORRECT trial provided further evidence for the benefit of continued VEGF targeting in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. In the CORRECT trial, adverse events (3°–4°) such as hand-foot skin reaction, diarrhea, and fatigue occurred more frequently in the regorafenib arm. Measurements of patients’ health-related quality-of-life and health utility values suggested, however, that deterioration in patients’ quality of life and health status were similar in both arms and were not negatively affected by regorafenib.

Together with the VELOUR and ML18147 studies, the CORRECT trial provided further evidence for the benefit of continued VEGF targeting in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer.

The trial was assessed as very well conducted by the SIGN checklist. The main contents and assessment of the trial are listed in Table 4.

Anti-EGFR Therapy

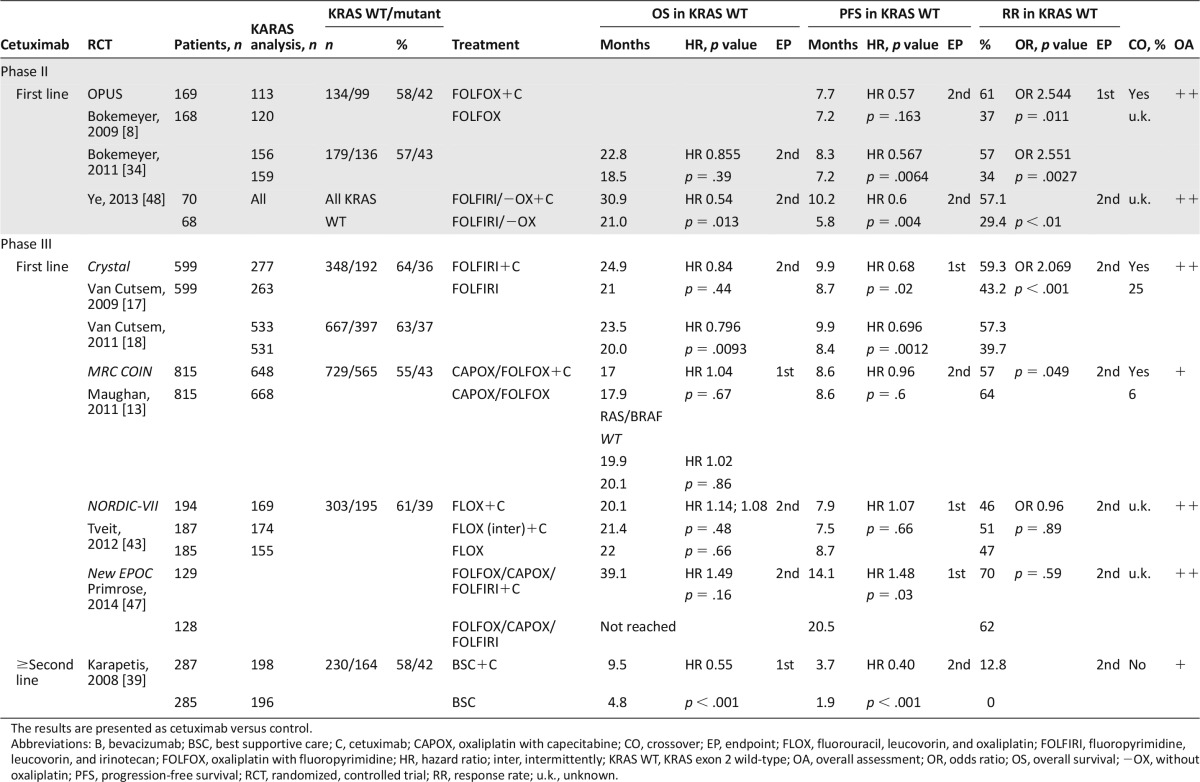

For first-line EGFR-targeted treatment, two phase II trial for cetuximab, four phase III trials for cetuximab, and one phase III trial for panitumumab were included. The phase II Opus study evaluated the addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX in EGFR-expressing tumors [8]. Within the retrospective analysis in patients with KRAS WT exon 2 (KRAS WT) tumors, the addition of cetuximab was associated with a significant increase in RR and a significantly lower risk of disease progression [34]. Emerging evidence indicates that extended RAS testing in KRAS exons 2–4 and in NRAS exons 2–4 is required to identify appropriate patients for anti-EGFR therapy. Overall, 179 patients with KRAS and 87 patients with RAS WT were evaluated in the OPUS trial [50]. In both populations, however, the addition of cetuximab did not significantly improve OS.

Three years later, the three-arm MRC COIN study was performed evaluating cetuximab in combination with FOLFOX/CAPOX continuously or intermittently in patients with KRAS WT tumors [13]. The comparison of intermittent FOLFOX/CAPOX with or without cetuximab was described in a companion paper. In this study, cetuximab increased RR but did not improve PFS or OS in KRAS WT patients. Improved PFS with cetuximab was, however, seen in patients treated with fluorouracil-based therapy and zero or one metastatic site. In the retrospective analysis of the COIN study, 581 patients were WT for KRAS exons 2, 3, and 4 and NRAS exons 2 and 3 and B-rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (BRAF). Even in the extended RAS and BRAF WT population, there was no significant OS benefit.

Another first-line combination of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy with cetuximab was investigated within the three-arm NORDIC-VII study [43]. Arm A received fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FLOX), whereas arm B received FLOX plus cetuximab continuously. In arm C, FLOX was usually stopped after 16 weeks of treatment, and cetuximab was continued as maintenance therapy. Endpoints were not significantly changed in the intention-to-treat population and irrespective of the KRAS mutational status. In patients with KRAS WT tumors, cetuximab did not provide any additional benefit compared with FLOX alone, and OS was similar in all three arms.

Recently, two studies evaluating the efficacy of cetuximab in combination with chemotherapy in patients with liver-limited disease were published. In the New EPOC study, the efficacy of perioperative oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy with or without cetuximab was evaluated in patients with potentially resectable liver metastases [47]. Patients who had received oxaliplatin as adjuvant therapy were permitted to be treated with irinotecan. Altogether, 51 patients received irinotecan-based therapy, and 182 patients received oxaliplatin-based therapy. Interestingly, despite a moderate improvement of response preoperatively, addition of cetuximab significantly reduced the primary endpoint PFS, and there was also a trend to a reduced OS. The second study evaluated the efficacy of cetuximab in Chinese patients with synchronous nonresectable liver metastasis [48]. After resection of the primary tumors, patients with KRAS WT were randomly assigned to receive chemotherapy FOLFIRI or FOLFOX with or without cetuximab. The primary endpoint was the rate of patients converted to resection for liver metastases, which was significantly improved by the addition of cetuximab. In contrast to the New EPOC study, cetuximab also significantly improved OR, PFS, and OS regardless of the applied chemotherapy regimen.

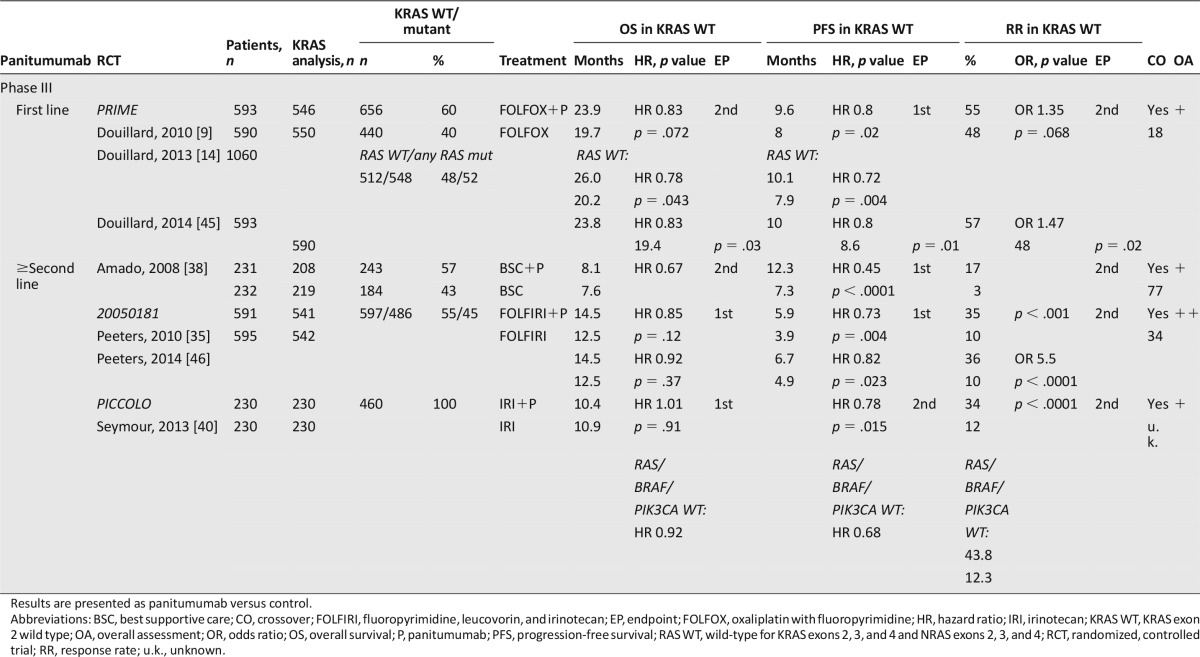

The phase III PRIME study evaluated panitumumab in combination with FOLFOX as first-line treatment [9, 14, 45]. In contrast to cetuximab, panitumumab in combination with FOLFOX significantly improved not only the primary endpoint PFS but also the secondary endpoint OS in patients with KRAS WT tumors. In the retrospective analysis of the PRIME study for KRAS and NRAS mutations beyond KRAS exon 2, 17% of the initially KRAS WT diagnosed patients had RAS mutation in other exons of KRAS and NRAS [14]. In patients with RAS WT, the benefit in OS provided by panitumumab increased by 6 months to a OS of 26 months in patients with RAS WT. In the RAS mutant groups receiving panitumumab, OS was significantly shorter compared with placebo.

As first-line combination of EGFR-targeted therapies with FOLFIRI, the phase III Crystal study analyzed the efficacy of cetuximab in patients with EGFR-expressing tumors [17]. In the retrospectively ascertained KRAS WT population, the addition of cetuximab significantly improved OS, PFS, and RR in patients with KRAS WT tumors [18]. Similar to the PRIME study, a retrospectively performed RAS analysis identified 63 patients with additional KRAS and NRAS mutations among 430 RAS evaluable, KRAS WT patients. OS increased in the RAS WT populations to 28.4 months [51].

Panitumumab was analyzed in three phase III trials in subsequent treatment lines. Peeters et al. [35, 46] analyzed the role of panitumumab in combination with FOLFIRI as second-line treatment in the 20050181 study. Patients were prospectively analyzed for KRAS mutations in exon 2. Panitumumab significantly improved PFS and RR in patients with KRAS WT tumors, whereas OS was only nonsignificantly improved. The results of the extended RAS analysis have very recently been presented; however, even in the subpopulation of patients with RAS WT tumors, panitumumab did not significantly improve OS [52]. In this study, 34% of the patients in the control arm received anti-EGFR antibodies in subsequent treatment.

Irinotecan with or without panitumumab was analyzed in a KRAS WT population following failure to FOLFOX therapy within the PICCOLO trial [40]. Only very few patients (2%) in each arm received bevacizumab prior to study inclusion. Addition of panitumumab to irinotecan did not improve the primary endpoint OS but improved the secondary endpoints PFS and RR. Similar results were obtained in the extended WT (RAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA) population. In patients with all WT tumors, panitumumab improved RR and PFS but did not prolong OS. In patients with any mutation, panitumumab had no effect on PFS and an adverse effect on OS.

Amado et al. [38] analyzed the efficacy of panitumumab as monotherapy versus BSC in chemoresistant patients with KRAS WT and mutated tumors. PFS and RR were improved by panitumumab in KRAS WT patients, although the difference was not evaluated for statistical significance. An OS benefit by panitumumab in KRAS WT patients was not shown; however, crossover of panitumumab in the control arm was higher than 70%. Similarly, cetuximab monotreatment significantly improved the primary endpoint OS and the secondary endpoints PFS and RR as last-line therapy in patients with KRAS WT compared with BSC within one phase III trial [53].

Together, in the first-line setting, there are very good results for a panitumumab-FOLFOX combination, whereas the phase III evidence for the combination of cetuximab with FOLFOX remains poor. Efficacy has been shown for cetuximab in combination with FOLFIRI in the first-line setting and as single agent in last-line setting. Similarly, efficacy has been shown for panitumumab in combination with FOLFIRI in second-line settings, albeit without a significant improvement in OS, and as monotherapy in last-line settings.

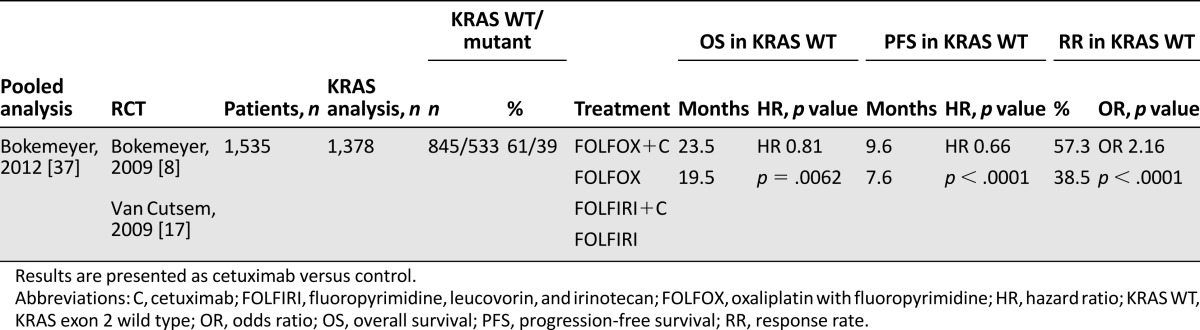

One review and meta-analysis and one pooled analysis for cetuximab were assessed that included the OPUS and Crystal trials and several biomarker analyses [33, 37]. In a pooled analysis on the combined population of patients evaluable for KRAS mutation status from the OPUS and Crystal study OS, PFS and RR were all significantly improved by cetuximab [37]. The heterogeneity was high among studies analyzed in the review. No analysis of OS was performed in KRAS WT patients with cetuximab versus no-cetuximab treatment. PFS and RR were both improved in this group. Cetuximab treatment achieved a statistical improvement in RR, PFS, and OS in patients with KRAS WT tumors compared with cetuximab-treated patients with mutated KRAS. Patients with mutated KRAS tumors and cetuximab treatment had a shorter OS and lower RR compared with the placebo group. The most common AEs related to cetuximab were skin toxicity/rash and gastrointestinal disorders, such as diarrhea and stomatitis. All trials were designed a priori open label because of the obvious anti-EGFR-related skin reactions. All trials for cetuximab were assessed very well or well conducted, whereas the review and meta-analysis for cetuximab was assessed poorly conducted by the SIGN checklist. The main contents and assessments of the trials for cetuximab are listed in Table 5, of the pooled analysis in Table 6, and of the review and meta-analysis in supplemental online Table 2.

Table 5.

Summary of the selected randomized, controlled trials, and according assessments by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network for cetuximab

Table 6.

Summary of the selected extended biomarker/pooled analyses and according assessments by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network for cetuximab

For panitumumab, one meta-analysis was assessed [36]. All patients included in the analysis had KRAS WT tumor status. Used in subsequent-line setting, panitumumab was associated with a significant improvement in PFS, a nonsignificant OS benefit, and a significant increase in RR. AE rates were generally comparable across arms with the exception of known toxicities associated with anti-EGFR therapy. The trials and the meta-analysis for panitumumab were assessed as very well and well conducted by the SIGN checklist. The main contents and assessments of the trials and meta-analysis are listed in Table 7 and supplemental online Table 3.

Table 7.

Summary of the selected randomized, controlled trials, and according assessments by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network for panitumumab

BRAF Testing

Considering BRAF mutations, its predictive role for anti-EGFR treatment in mCRC is still controversial. Being detected in only 6%–9% of tumor samples [18, 37], there is so far only evidence for a poor prognosis for patients with BRAF mutated tumors [13, 18, 37, 54–59].

Conclusion

When chemotherapy was the sole therapeutic option for patients with mCRC, OS was stagnant at approximately 16–19 months. With the introduction of targeted therapies, OS in selected patient populations increased to more than 30 months in most recent trials. Here, we summarized the currently available evidence for the addition of targeted therapies to chemotherapy in first and subsequent treatment lines.

The efficacy of bevacizumab plus any 5-FU-based chemotherapy was proven as first- and second-line therapy by means of several large, well and very well conducted phase II and III trials. Therapy with bevacizumab alone resulted in an poorer survival compared with combinations with chemotherapy and hence did not enter into clinical practice [16]. In first-line settings, addition of bevacizumab significantly improved OS in combination with the IFL regimen [16]. Meanwhile, IFL has largely been replaced by FOLFIRI, which is more effective and better tolerated than the IFL regimen [60]. Formally, it has not been shown that bevacizumab in combination with FOLFIRI as first-line treatment increases OS [26]. Three phase III trials presented as abstracts: TRIBE [61], FIRE-3 [62], and SAKK41/06 [63] consistently revealed a median OS of 25 months in patients receiving bevacizumab in combination with infusional 5-FU/irinotecan-based first-line chemotherapy. The addition of bevacizumab to 5-FU-based therapy alone or in combination with oxaliplatin improved PFS and RR in four assessed trials [20, 22, 24, 25]. These results are further supported by the recently published AVEX phase III trial analyzing the efficacy of bevacizumab in combination with capecitabine in elderly patients [44]. In second-line settings, bevacizumab improved OS, PFS, and RR in combination with FOLFOX and irinotecan-based therapy [7, 23]. Moreover, the ML18147 and the phase II BEBYP study [64] trial provided evidence to the hitherto controversial approach to maintain therapy with bevacizumab beyond progression in combination with chemotherapy.

Aflibercept has been identified as an additional option to target angiogenesis in mCRC [15]. Based on the VELOUR trial, aflibercept has been established as second-line treatment in combination with FOLFIRI after oxaliplatin failure. Its efficacy was independent of bevacizumab in first-line settings. The magnitude of benefit on OS and PFS was similar to what was seen with bevacizumab in the ML18147 study, although this study also included more difficult-to-treat patients with rapid progression in first line.

Lately, the tyrosine kinase inhibitor regorafenib targeting VEGF receptors and Tie-2 among other pathways has been approved as monotherapy, based on a significant improved OS compared with placebo in patients who failed all standard therapies including bevacizumab and anti-EGFR agents in KRAS WT [42]. These two trials provide further evidence to continue VEGF targeting in subsequent therapy beyond progressive disease.

Cetuximab has here been analyzed in six large, well and very well conducted phase II and III trials providing evidence for its efficacy to prolong OS in first-line therapy in combination with FOLFIRI and in last-line therapy as a single agent. Similarly, efficacy on OS has been shown for panitumumab in combination with FOLFOX in first-line therapy and as a single agent in last-line therapy [9, 38, 45, 65]. Concerning the combination of cetuximab with FOLFOX in first-line settings, the phase II OPUS trial demonstrated a significant increase in RR and PFS and a nonsignificant benefit for OS in the retrospectively ascertained patients with KRAS WT tumors. Neither of the subsequent phase III trials, Nordic-VII and MCR COIN, were able to confirm the benefit in PFS and OS by the addition of cetuximab to oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy [13, 43]. Moreover, the addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy in patients with liver-limited disease remains controversial. Cetuximab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy was detrimental to KRAS WT patients with resectable liver metastases receiving perioperative therapy within the NEW EPOC trial [47]. In contrast to these findings, the addition of cetuximab to oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-based chemotherapy significantly improved not only the R0-resection rate but also OS in Chinese patients with synchronous nonresectable liver-limited metastases.

In second-line settings, the efficacy of cetuximab in combination with irinotecan after failure of irinotecan- or oxaliplatin-based pretreatment is based on the results of the BOND and EPIC studies [11, 66]. Cetuximab alone or in combination with irinotecan improved RR and PFS, whereas OS remained unchanged. The BOND study lacked a noncetuximab control arm, and the KRAS status was only available in a minority of patients in both studies. The efficiency of panitumumab in second-line settings has been determined in combination with FOLFIRI or irinotecan revealing a significant benefit in PFS and RR in KRAS WT patients [35, 40]. However, OS was not significantly improved in both studies.

Cetuximab as single agent significantly improved OS and PFS as compared with BSC in patients with KRAS WT tumors in last-line therapy [53]. Likewise single-agent panitumumab has been shown to be effective in patients with chemotherapy-refractory KRAS WT tumors as last-line treatment [38]. OS was not improved, most likely because of the high crossover rate in the placebo group. Accordingly, the efficacy of panitumumab and cetuximab was similar in patients with KRAS WT tumors in the recently published phase III ASPECCT trial [67].

Emerging data strongly support further refinement in molecular selection to derive substantial benefit from any EGFR-targeted therapy. The first evidence for additional mutations in KRAS and NRAS in up to 18% of patient with KRAS exon 2 WT tumors was provided by retrospective analyses of the PRIME and 181 trials [14, 68]. In the PRIME study, the updated analyses revealed a more pronounced benefit in OS for patients with RAS WT tumors compared with patients with KRAS WT treated with panitumumab. Moreover, the analysis confirmed the detrimental effects of the antibody for patients with any mutation in the NRAS and KRAS genes. These data are supported by updated analysis from the FIRE-3 [69] and Crystal trials [51], in which patients with RAS WT tumors treated with the EGFR antibodies had a greater therapeutic benefit compared with patients with KRAS WT tumors. In the extended RAS analysis of the 181 study, the benefits in the RAS WT population became more definite as compared with the KRAS WT population, but the benefit for OS still did not reach statistical significance. Similarly, the more stringent RAS analysis did not identify a subpopulation in the OPUS and PICCOLO trials that would benefit from the addition of EGFR antibodies in terms of OS and did not significantly improve the detrimental effects observed in the KRAS WT population with liver metastasis treated with cetuximab.

In the PRIME study, the updated analyses revealed a more pronounced benefit in OS for patients with RAS WT tumors compared with patients with KRAS WT treated with panitumumab.

Finally, the trials published so far also provide evidence that the RAS analysis is not only of predictive importance but also of prognostic significance: patients with KRAS WT tumors survived longer compared with patients with KRAS mutant tumors, and patients with WT tumors in the extended RAS analysis survived longer compared with patients with mutations in any RAS gene [13, 35, 70]. Accordingly, several studies revealed a longer OS in patients with KRAS WT tumors compared with patients with KRAS mutated tumors treated with bevacizumab and regorafenib [41, 42, 71–74].

Altogether, several therapeutic options are available for patients with mCRC in 2014. The addition of targeted therapies to chemotherapy has not always resulted in significant improvement of OS. Some of the trials were not powered to detect differences in OS, whereas unexpected toxicity or high crossover rates may have contributed to the lack of OS benefit in other trials. Nevertheless, physicians need to be aware of all available evidence to choose the best treatment and the best treatment strategy for patients with mCRC.

Of great interest and controversy, the first head-to-head comparisons of EGFR antibodies and bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy in patients with KRAS WT tumors, the phase III FIRE-3 trial [62], the phase II PEAK trial [61], and the CALGB/SWOG 80405 trial [75] have been presented. All trials were negative for their primary endpoints OR, PFS, and OS, respectively. Moreover, there was no significant difference in OR and PFS (not yet reported for the CALGB/SWOG 80405 trial). In contrast, OS was significantly better in the RAS WT population of the FIRE-3 study treated with cetuximab compared with patients treated with bevacizumab in first-line settings (nonsignificant benefit in the PEAK trial). The OS curves separated after approximately 2 years in all three trials, suggesting that not only first-line but also second-line treatment may have contributed to the OS difference. Finally, all three studies did not incorporate treatment strategies such as the ML18147 concept for bevacizumab, which makes it difficult to give a definitive answer to the question of which antibody should be used in the first-line setting in RAS WT patients. The future challenge therefore remains to identify the patients that will benefit the most from specific targeted treatment among the emerging combinations and treatment sequences.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Supplementary Material

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Martha M. Kirstein, Ansgar Lange, Anne Prenzler, Michael P. Manns, Stefan Kubicka, Arndt Vogel

Provision of study material or patients: Martha M. Kirstein, Ansgar Lange, Anne Prenzler, Michael P. Manns, Stefan Kubicka, Arndt Vogel

Collection and/or assembly of data: Martha M. Kirstein, Ansgar Lange, Anne Prenzler, Michael P. Manns, Stefan Kubicka, Arndt Vogel

Data analysis and interpretation: Martha M. Kirstein, Ansgar Lange, Anne Prenzler, Michael P. Manns, Stefan Kubicka, Arndt Vogel

Manuscript writing: Martha M. Kirstein, Ansgar Lange, Anne Prenzler, Michael P. Manns, Stefan Kubicka, Arndt Vogel

Final approval of manuscript: Martha M. Kirstein, Ansgar Lange, Anne Prenzler, Michael P. Manns, Stefan Kubicka, Arndt Vogel

Disclosures

Stefan Kubicka: Roche, Amgen, Merck, Sanofi, Bayer (H); Roche, Amgen, Merck, Bayer (C/A); Roche (other); Arndt Vogel: Roche, Bayer, Merck (H); Roche, Bayer, Amgen (C/A); Roche, Bayer (other). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, et al. Cancer statistics, 2011: The impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim HJ, Gill S, Speers C, et al. Impact of irinotecan and oxaliplatin on overall survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A population-based study. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:153–158. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0942001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poston GJ, Figueras J, Giuliante F, et al. Urgent need for a new staging system in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4828–4833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.6453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colucci G, Gebbia V, Paoletti G, et al. Phase III randomized trial of FOLFIRI versus FOLFOX4 in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: A multicenter study of the Gruppo Oncologico Dell’Italia Meridionale. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4866–4875. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3677–3683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welch S, Spithoff K, Rumble RB, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for patients with advanced colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1152–1162. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennouna J, Sastre J, Arnold D, et al. Continuation of bevacizumab after first progression in metastatic colorectal cancer (ML18147): A randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:663–671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J, et al. Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) versus FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: The PRIME study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4697–4705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonker DJ, O’Callaghan CJ, Karapetis CS, et al. Cetuximab for the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2040–2048. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:337–345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, et al. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:753–762. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maughan TS, Adams RA, Smith CG, et al. Addition of cetuximab to oxaliplatin-based first-line combination chemotherapy for treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: Results of the randomised phase 3 MRC COIN trial. Lancet. 2011;377:2103–2114. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60613-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1023–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Cutsem E, Tabernero J, Lakomy R, et al. Addition of aflibercept to fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan improves survival in a phase III randomized trial in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3499–3506. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Láng I, et al. Cetuximab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: Updated analysis of overall survival according to tumor KRAS and BRAF mutation status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2011–2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabbinavar FF, Schulz J, McCleod M, et al. Addition of bevacizumab to bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin in first-line metastatic colorectal cancer: Results of a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3697–3705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabbinavar F, Hurwitz HI, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Phase II, randomized trial comparing bevacizumab plus fluorouracil (FU)/leucovorin (LV) with FU/LV alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:60–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hochster HS, Hart LL, Ramanathan RK, et al. Safety and efficacy of oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine regimens with or without bevacizumab as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: Results of the TREE Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3523–3529. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurwitz HI, Fehrenbacher L, Hainsworth JD, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with fluorouracil and leucovorin: An active regimen for first-line metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3502–3508. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giantonio BJ, Catalano PJ, Meropol NJ, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: Results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1539–1544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saltz LB, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: A randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2013–2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tebbutt NC, Wilson K, Gebski VJ, et al. Capecitabine, bevacizumab, and mitomycin in first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: Results of the Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group Randomized Phase III MAX Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3191–3198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.7723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stathopoulos GP, Batziou C, Trafalis D, et al. Treatment of colorectal cancer with and without bevacizumab: A phase III study. Oncology. 2010;78:376–381. doi: 10.1159/000320520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao Y, Tan A, Gao F, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing chemotherapy plus bevacizumab with chemotherapy alone in metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:677–685. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0655-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macedo LT, da Costa Lima AB, Sasse AD. Addition of bevacizumab to first-line chemotherapy in advanced colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis, with emphasis on chemotherapy subgroups. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loupakis F, Bria E, Vaccaro V, et al. Magnitude of benefit of the addition of bevacizumab to first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:58. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galfrascoli E, Piva S, Cinquini M, et al. Risk/benefit profile of bevacizumab in metastatic colon cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabbinavar FF, Hurwitz HI, Yi J, et al. Addition of bevacizumab to fluorouracil-based first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: Pooled analysis of cohorts of older patients from two randomized clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:199–205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabbinavar FF, Hambleton J, Mass RD, et al. Combined analysis of efficacy: the addition of bevacizumab to fluorouracil/leucovorin improves survival for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3706–3712. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chuko JYM, Chen BJ, Hu KY. Efficacy of cetuximab on wild-type and mutant kras in colorectal cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Sci. 2010;30:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Hartmann JT, et al. Efficacy according to biomarker status of cetuximab plus FOLFOX-4 as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: The OPUS study. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1535–1546. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peeters M, Price TJ, Cervantes A, et al. Randomized phase III study of panitumumab with fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) compared with FOLFIRI alone as second-line treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4706–4713. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.6055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ibrahim EM, Abouelkhair KM. Clinical outcome of panitumumab for metastatic colorectal cancer with wild-type KRAS status: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Med Oncol. 2011;28(suppl 1):S310–S317. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9760-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bokemeyer C, Van Cutsem E, Rougier P, et al. Addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy as first-line treatment for KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: Pooled analysis of the CRYSTAL and OPUS randomised clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1466–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1626–1634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.7116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seymour MT, Brown SR, Middleton G, et al. Panitumumab and irinotecan versus irinotecan alone for patients with KRAS wild-type, fluorouracil-resistant advanced colorectal cancer (PICCOLO): A prospectively stratified randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:749–759. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hurwitz HI, Tebbutt NC, Kabbinavar F, et al. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer: Pooled analysis from seven randomized controlled trials. The Oncologist. 2013;18:1004–1012. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): An international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:303–312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61900-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tveit KM, Guren T, Glimelius B, et al. Phase III trial of cetuximab with continuous or intermittent fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (Nordic FLOX) versus FLOX alone in first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: The NORDIC-VII study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1755–1762. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cunningham D, Lang I, Marcuello E, et al. Bevacizumab plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in elderly patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer (AVEX): An open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J, et al. Final results from prime: Randomized phase 3 study of panitumumab with folfox4 for first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1346–1355. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peeters M, Price TJ, Cervantes A, et al. Final results from a randomized phase 3 study of folfiri {+/–} panitumumab for second-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:107–116. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Primrose J, Falk S, Finch-Jones M, et al. Systemic chemotherapy with or without cetuximab in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastasis: The New EPOC randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:601–611. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye LC, Liu TS, Ren L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of cetuximab plus chemotherapy for patients with KRAS wild-type unresectable colorectal liver-limited metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1931–1938. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.8308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guan ZZ, Xu JM, Luo RC, et al. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab plus chemotherapy in Chinese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A randomized phase III ARTIST trial. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:682–689. doi: 10.5732/cjc.011.10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tejpar S, Lenz H, Köhne C, et al. Effect of KRAS and NRAS mutations on treatment outcomes in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) treated first-line with cetuximab plus FOLFOX4:New results from the OPUS study. ASCO. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 3):LBA444a. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ciardiello F, Lenz H, Köhne C, et al. Effect of KRAS and NRAS mutational status on first-line treatment with FOLFIRI plus cetuximab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): New results from the CRYSTAL trial. ASCO. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 3):LBA443a. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peeters M, Oliner KS, Price TJ, et al. Analysis of KRAS/NRAS mutations in phase 3 study 20050181 of panitumumab (pmab) plus FOLFIRI versus FOLFIRI for second-line treatment (tx) of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). ASCO GI. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 3):LBA387a. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karapetis C, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker D, et al. Kras mutation status is a predictive biomarker for cetuximab benefit in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: Results from ncic ctg co.17: A phase III trial of cetuximab versus best supportive care. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(suppl):v2–v5. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, et al. Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5705–5712. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saridaki Z, Tzardi M, Papadaki C, et al. Impact of KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutations, PTEN, AREG, EREG expression and skin rash in ≥ 2 line cetuximab-based therapy of colorectal cancer patients. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Souglakos J, Philips J, Wang R, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of common mutations for treatment response and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:465–472. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perrone F, Lampis A, Orsenigo M, et al. PI3KCA/pten deregulation contributes to impaired responses to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:84–90. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sartore-Bianchi A, Martini M, Molinari F, et al. PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with clinical resistance to EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1851–1857. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prenen H, De Schutter J, Jacobs B, et al. PIK3CA mutations are not a major determinant of resistance to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3184–3188. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fuchs CS, Marshall J, Barrueco J. Randomized, controlled trial of irinotecan plus infusional, bolus, or oral fluoropyrimidines in first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: Updated results from the BICC-C study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:689–690. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Falcone A, Cremolini C, Masi G, et al. FOLFOXIRI/bevacizumab (bev) versus FOLFIRI/bev as first-line treatment in unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients (pts): Results of the phase III TRIBE trial by GONO group. ASCO. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl):3505a. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heinemann V, Fischer von Weikersthal L, Decker T, et al. Randomized comparison of FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment of KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: German AIO study KRK-0306 (FIRE-3) ASCO. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl):LBA3506. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koeberle D, Betticher DC, Von Moos R, et al. Bevacizumab continuation versus no continuation after first-line chemo-bevacizumab therapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A randomized phase III noninferiority trial (SAKK 41/06). ASCO. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl):3503. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Masi G, Loupakis F, Salvatore L, et al. Second-line chemotherapy (CT) with or without bevacizumab (BV) in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients (pts) who progressed to a first-line treatment containing BV: Updated results of the phase III “BEBYP” trial by the Gruppo Oncologico Nord Ovest (GONO). ASCO. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl):3615. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Douillard JY, Sienna S, Davison C, et al. Benefit of adding panitumumab to folfox4 in patients with kras/nras wild-type (wt) metastatic colorectal cancer (mcrc): A number-needed-to-treat (nnt) analysis. Value Health. 2013;16:A395. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sobrero AF, Maurel J, Fehrenbacher L, et al. EPIC: Phase III trial of cetuximab plus irinotecan after fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin failure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2311–2319. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Price TJ, Peeters M, Kim TW, et al. Panitumumab versus cetuximab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory wild-type KRAS exon 2 metastatic colorectal cancer (ASPECCT): A randomised, multicentre, open-label, non-inferiority phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:569–579. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peeters M, Oliner KS, Price TJ, et al. Updated analysis of KRAS/NRAS and BRAF mutations in study 20050181 of panitumumab (pmab) plus FOLFIRI for second-line treatment (tx) of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). ASCO. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl):3568a. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stintzing S, Jung A, Rossius L, et al. ECC 2013 LBA 17: Analysis of KRAS/NRAS and BRAF Mutations in FIRE-3: A Randomized Phase III Study of FOLFIRI Plus Cetuximab or Bevacizumab as First-Line Treatment for Wild-Type (WT) KRAS (Exon 2) Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (mCRC) Patients. ESMO. . 2013:LBA17a. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schwartzberg LS, Rivera F, Karthaus M, et al. PEAK: A randomized, multicenter phase II study of panitumumab plus modified fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX6) or bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with previously untreated, unresectable, wild-type KRAS exon 2 metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2240–2247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Díaz-Rubio E, Gómez-España A, Massutí B, et al. Role of Kras status in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy plus bevacizumab: A TTD group cooperative study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Petrelli F, Coinu A, Cabiddu M, et al. KRAS as prognostic biomarker in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with bevacizumab: A pooled analysis of 12 published trials. Med Oncol. 2013;30:650. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0650-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bruera G, Cannita K, Di Giacomo D, et al. Worse prognosis of KRAS c.35 G > A mutant metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC) patients treated with intensive triplet chemotherapy plus bevacizumab (FIr-B/FOx) BMC Med. 2013;11:59. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hurwitz HI, Yi J, Ince W, et al. The clinical benefit of bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer is independent of K-ras mutation status: Analysis of a phase III study of bevacizumab with chemotherapy in previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. The Oncologist. 2009;14:22–28. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz H, et al. CALGB/SWOG 80405: Phase III trial of irinotecan/5-FU/leucovorin (FOLFIRI) or oxaliplatin/5-FU/leucovorin (mFOLFOX6) with bevacizumab (BV) or cetuximab (CET) for patients (pts) with KRAS wild-type (wt) untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum (MCRC) J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 5):LBA3a. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.