Abstract

The MAPK/ERK pathway is activated by upstream genomic events and/or activation of multiple signaling events where information coalesces at this important nodal pathway point. This pathway is tightly regulated under normal conditions by phosphatases and bidirectional communication with other pathways, such as the AKT/m-TOR pathway. Recent evidence indicates that the MAPK/ERK signaling node can function as a tumor suppressor as well as the more common pro-oncogenic signal. The effect that predominates depends on the intensity of the signal and the context or tissue in which the signal is aberrantly activated. Genomic profiling of tumors has revealed common mutations in MAPK/ERK pathway components, such as BRAF. Currently approved for the treatment of melanoma, inhibitors of B-RAF kinase (BRAFi) are being studied alone and in combination with inhibitors of the MAPK and other pathways to optimize treatment of many tumor types. Therapies targeted toward MAPK/ERK components have variable response rates when used in different solid tumors, such as colorectal cancer and ovarian cancer. Understanding the differential nature of activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway in each tumor type is critical in developing single and combination regimens, as different tumors have unique mechanisms of primary and secondary signaling and subsequent sensitivity to drugs.

Keywords: MAPK, BRAF, ERK, MEK, signaling, melanoma, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer

Introduction

Great advances have been made toward understanding the genomic characterization of solid and hematological malignancies. Collaborative projects, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)1, have revealed the molecular complexity of tumors, and also the challenges inherent in data interpretation and clinical application. Differentiation of targetable driver mutations from genetic and genomic noise and passenger mutations is one of the most important goals of genome and epigenome analysis.2, 3 Driver mutations lead to dysregulation of signaling pathways, increasing malignant behavior4. Many of these gain-of-function driver mutations have been shown to be druggable, leading to the development of small molecules and antibodies that target specific events such as the ligand-binding site of the receptor, or the ATP binding site in the kinase domain of specific kinase proteins.

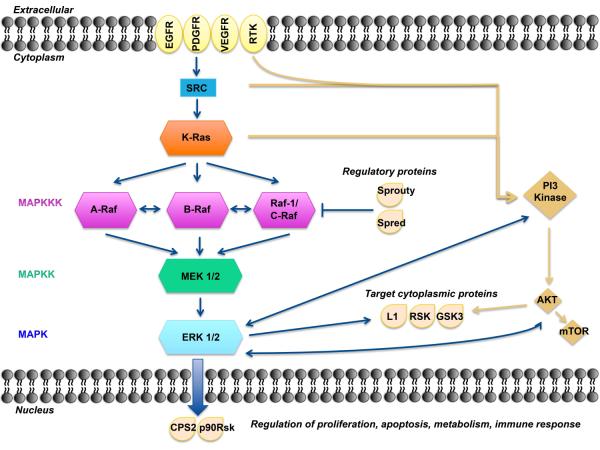

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade is a critical pathway for human cancer cell survival, dissemination, and resistance to drug therapy.5 The MAPK/ERK (extracellular signal regulated kinases) pathway is a convergent signaling node receiving input from numerous stimuli, including internal metabolic stress and DNA damage pathways, and altered protein concentrations, as well as via signaling from external growth factors, cell-matrix interactions, and communication from other cells.6 Mutated genes responsible for regulation of cell fate, genome integrity, and survival can lead to increased protein amplification and alter the tumor microenvironment, thus over-activating the pathway.7 These mutations can occur upstream in membrane receptor genes, such as epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR)8, in signal transducers (RAS)9, regulatory partners (Sprouty)10, and in downstream kinases belonging to MAPK/ERK pathway itself (BRAF; Figure 1).11,12 Several mutations involving the MAPK/ERK pathway have been identified in human cancers and are ripe for targeting. Current and future drug development efforts will need to alter and regulate tumor signaling in this complex network of co-dependent pathways.

Figure 1.

A model of the MAPK/ERK pathway. After membrane receptor activation, adaptor proteins recruit RAS proteins to activate steps concluding with ERK activation. Successive steps of phosphorylation amplify the signal, Raf→MEK→ERK, until ERK activates its cytoplasmic and/or nuclear targets. Regulatory phosphatases, Sprouty and Spred, modulate the intensity of the signal. The PI3K-AKT pathway interacts with the MAPK/ERK node under normal conditions and in the cancer cell. Target cytoplasmic proteins include RSK, ribosomal S6 kinases; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; L1, adhesion molecule L1. Additional proteins in nucleus include CPS2, p90Rsk.

The MAPK pathway and its regulation

There are four independent MAPK pathways composed of four signaling families: the MAPK/ERK family or classical pathway, and Big MAP kinase-1 (BMK-1), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 signaling families.13 These families share a basic organization composed of two serine/threonine kinases and one double specificity threonine/tyrosine kinase.14 Generically, these kinases are designated from upstream to downstream, closer to the nucleus, as MAPK kinase-kinase (MAPKKK), MAPK kinase (MAPKK) and MAPK (Figure 1).5 The canonical MAPK/ERK pathway is composed of three types of MAPKKK: A-RAF, B-RAF and RAF-1 or C-RAF kinases. BRAF is the gene most commonly mutated at this level in human cancer. One level below are the MAPKKs, which are composed of MEK1 and MEK2. Finally, further downstream are ERK1 and ERK2, which are the final effectors of the MAPK pathway.15

ERK phosphorylation results in the activation of multiple substrates that are responsible for stimulation of cell proliferation. Spatial localization of ERK determines target substrates and later effects within the cell.6 When located in the cytoplasm, ERK phosphorylates cytoskeletal proteins that affect cell movement and trafficking,16 metabolism, cell adhesion, and nodal regulation of other pathways.17 Cytoplasmic substrates include ribosomal S6 kinases (RSK) that regulate glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) involved in metabolism, and L1 adhesion molecule, a protein of neural origin, that participates in cell adhesion.18, 19 Minutes after MAPK/ERK activation, ERK detaches from cytoplasmic anchoring proteins, and translocates to the nucleus to exert its transcriptional regulation.20 Active ERK in the nucleus causes phosphorylation and activation of various transcription factors, such as carbamoyl phosphate synthetase II (CPS II) linking with synthesis of DNA or p90RSK and promoting cell cycle progression. These two events are integral in MEK/ERK stimulation of cell proliferation.21, 22 In immune cells, activated ERK is also a component of the innate response in different steps of the inflammatory cascade, increasing the expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS).23

In addition to spatial activation, the final effect of MAPK/ERK pathway is modulated by timing, duration, and intensity of its signal. Winters et al examined the MAPK/ERK cascade in different times points in colorectal cancer cell lines under the combination of carboxyamidotriazole, a intracellular calcium regulator, plus the selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor, celecoxib. Suppression of ERK activation occurred in the first hour of treatment, in contrast with the sustained ERK phosphorylation after 9 days of treatment.24 Indeed cells interpret and respond differently to small changes in the levels of MAPK/ERK activation. As described by Murphy et al, c-FOS, an early gene product of MAPK/ERK activation, works as a sensor of the duration of ERK stimulation. When the MAPK/ERK signal is transient, c-FOS is unstable and degraded in the nucleus, but if the signal is sustained c-FOS is phosphorylated, and specific domains are exposed promoting more ERK activation. 25 The pro-carcinogenic or pro-apoptotic signaling of this pathway is dependent upon the timing and duration of MAPK/ERK activation.

Specific proteins, such as kinase suppressor Ras-1 (KSR1), work as the main scaffold for proteins related to MAPK/ERK pathway activation. Cytoplasmic proteins, Sprouty and Spred, directly inhibit the pathway26 by removing activating phosphate groups from ERK, therefore decreasing its ability to phosphorylate its substrates.12 Thus, there are regulatory events both in the cytoplasm and the nucleus, along with spatial and temporal regulation that fine tune the output of the MAPK/ERK pathway.

Overactivated and oncogenic drivers of the MAPK pathway as therapeutic targets

Cellular proliferation is driven by an intricate network of regulated, interdependent signals. The complexity of the MAPK pathway is not random; it allows for the periodic environmental adaptation necessary for activation and regulation of the coordinated events critical for cell survival.27 MAPK/ERK pathway activation and subsequent interactions are highly regulated processes that are deregulated in cancer cells. Stimulation of growth factor receptors in the cell membrane leads to activation of two different but interconnected pivotal pathways: the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signal causing activation of AKT and its downstream substrates, and the MAPK/ERK pathway (Figure 1). Both drive cell proliferation, survival, and dissemination. The PI3K/AKT pathway also promotes anabolism; whereas, the MAPK/ERK pathway is more active in proliferation and invasion.5 Upregulation of MAPK/ERK signaling occurs as a result of overexpression or aberrant activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) or their immediate downstream targets, PI3K, SRC, and RAS.

Normal MAPK/ERK function is also responsible for tumor suppression through induction of senescence and ubiquitinization and degradation of proteins necessary for cell cycle activity and survival.28 Senescence involves the inhibition of cell proliferation through terminal cell cycle arrest.29 Abnormal activation of MAPK/ERK by RAS causes degradation of proteins required for both migration and progression through the cell cycle, as shown in a model of normal fibroblasts and validated in prostate benign tumors. In these tumors, high levels of phospho-ERK were found coexpressed with markers of senescent p16INK4a and PML, a marker of protein degradation.28 In addition, a screening study using a panel of silencing RNAs (shRNAs) against MEK1 increased lymphomagenesis in MYC-expressing lymphoid cells, demonstrating that MEK1 has tumor suppressor properties, and that the function of MEK1 kinase is context dependent. 30

Genetic mutations can dysregulate kinase activity and hyperactivate the MAPK pathway during induction and progression of tumorigenesis. Many oncogenic driver mutations have been identified in genes upstream of MAPK/ERK, varying across cancer types, as shown in Table 1. These may include exon 21 mutations in EGFR or del19EGFR, mutations in KRAS, and the classic V600EBRAF mutation. These mutated genes lead to downstream overactivation of the MAPK/ERK pathway. In general, mutations affecting MAPK/ERK pathway are singular, independent events. Infrequently, two mutations can be found in the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway within the same tumor, demonstrating tumoral molecular heterogeneity.31 The sensitivity of mutation detection depends upon the dominant population of cells represented in the tumor sample that is tested and thus may not be illustrative of the tumor as a whole.32

Table 1.

Frequency of mutations in the activators and components of MAPK/ERK pathway across different tumors.

Discovery of specific oncogene mutations that activate the MAPK pathway has spurred development of targeted therapies that apply to multiple tumor types. Studies in tumor cells with mutant V600EBRAF have demonstrated that RAF kinase inhibitors prevent ERK signaling.33 The selective MEK inhibitor, PD0325901, decreased cyclin D1 protein expression, and thereby decreased cell proliferation in BRAF mutant melanoma xenograft models.34 High plasma concentrations of the RAF inhibitor, vemurafenib, are associated with strong ERK pathway inhibition. Patients with advanced stage, V600EBRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma receiving vemurafenib treatment who achieved >80% inhibition of cytoplasmic ERK phosphorylation, shown in paired pre- and on-treatment biopsy samples, demonstrated clinical evidence of partial remission.35 Recently, immunomodulatory effects of BRAF inhibition were examined and shown to explain part of the efficacy of vemurafenib in melanoma. BRAF and MEK inhibition increased the expression of melanoma antigens in melanoma cell lines. This could increase T cell recognition of the tumor leading to a successful immunotherapeutic approach. 36

The next proteins downstream, MEK1 and MEK2, have now been successfully targeted. Selumetinib has shown some activity in metastatic biliary cancers in a study of 28 patients yielding a response rate (RR) of 12% and progression free survival (PFS) of 3.7 months. Only two patients were found to have RAS mutations and neither responded to therapy.37 Selumetinib was also studied in 24 patients with metastatic papillary or poorly differentiated thyroid cancer refractory to radioiodine treatment. It increased the iodine-124 uptake in twelve patients with responses to radioiodine in 5 of 8. Mutations were detected in seven of the eight patient treated; responses were reported in four patients with NRAS and one with a BRAF mutation.38 Docetaxel with or without selumetinib was examined in a randomized phase II trial of 87 patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with KRAS mutations. The RR was 37% in the experimental arm vs 0 (p < 0.0001), with PFS 5.3 versus 2.1 months (p=0.014).39 There are currently many ongoing phase II clinical trials exploring the use of agents targeting BRAF (Table 3) and MEK kinases (Table 4). Many of these trials apply mutational analyses for study eligibility to enrich for patients who may be most likely to benefit. Data suggest that this pathway behavior is not consistent in all settings, making targeting the addictive oncogenic pathway a challenge across different tumor types.

Table 3.

Phase II Ongoing Clinical trials for BRAF inhibitors in patients with solid tumors

| Tumor type | ||

|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | Other Tumor Types | |

| BRAF inhibitors | ||

| Vemurafenib |

|

|

| Dabrafenib |

|

|

Table 4.

Phase II trials of MEK inhibitors across tumor types

| Tumor type | ||

|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | Other Tumor Types | |

| Selumetinib |

|

|

| Trametinib |

BRAF inhibitor + trametinib: |

BRAF inhibitor + trametinib:

|

| Pimasertib |

|

|

| Refametinib |

|

|

The MAPK/ERK pathway is a double-edged sword. Generally, therapeutic inhibition of elements within this pathway has yielded some benefit. However, small molecule inhibitor therapy aimed at specific protein targets within the MAPK/ERK pathway has resulted in development of secondary malignancies. RAF inhibitors, as a class, may cause abnormal skin cell proliferation leading to keratoacanthomas or squamous cell cancers in approximately 10 to 20% of the patients.40-42 The development of these lesions is due to paradoxical activation of the normal MAPK/ERK pathway in the genomically normal skin keratinocytes.42 The combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors in metastatic melanoma resulted in improved treatment safety by counterbalancing the activation of the normal MAPK/ERK pathway yielding a marked reduction in the frequency of the paradoxical oncogenic skin changes.43, 44 The combination of dabrafenib (BRAFi) with trametinib (MEKi) caused keratoacanthomas in 7% and rare squamous cell skin cancers compared with a 19% frequency with dabrafenib alone.43 This safer combination is now under evaluation in numerous other cancers.

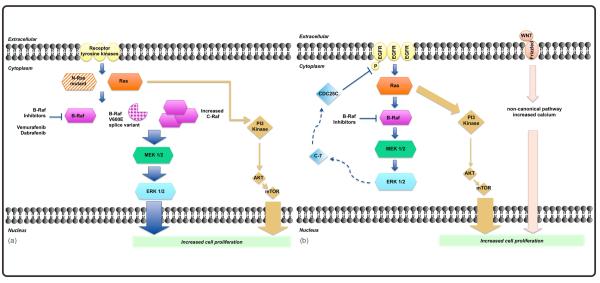

MAPK/ERK pathway susceptibility varies by tumor type

Different morphomolecular human tumors have demonstrated unexpected differential responses to signal interruption and may develop unique mechanisms of primary and secondary resistance (Table 2).45-47 Colorectal and low grade serous ovarian cancers harbor the same mutations as seen melanoma, KRAS and BRAF, with very different responses to inhibition of the MAPK/ERK pathway (Figure 2). The relative importance of MAPK/ERK in cancer cells is thus dependent on the cell and/or tissue of origin, magnitude of addictive dependence to the pathway, and mechanisms of escape or alternative signaling.

Table 2.

Mechanisms of primary and secondary resistance to TKIs in different tumor types.

| Tumor | Mechanism of resistance | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | |

| Lung | MET amplification90 BIM polymorphism91, 92 |

T790M mutation93 EGFR amplification94 Her2 amplification95 PIK3CA mutations94 MET amplification96 |

| Melanoma | NF1 loss97, 98 PTEN loss48 |

BRAF amplification55 NRAS amplification Increase in CRAF52 Splice variant BRAF54 Increase activation AKT99 NF1 loss97 |

| Colorectal | EGFR activation62, 100 PI3K/AKT activation63 Wnt/Ca++ activation64 |

N/A |

| Ovarian | PI3K activation101 Activation of ERα74 |

N/A |

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of resistance to BRAF inhibitors. A) In melanoma mechanisms of secondary resistance to BRAF inhibitors include BRAF splice variants expression, CRAF activation (all of which activate MAPK/ERK) or signaling trough alternatives pathways AKT/m-TOR etc. (see table 2) B) In Colorectal cancer, primary resistance to BRAF inhibitors is caused by direct activation of EGFR and AKT/m-TOR pathway.

Melanoma

The success of RAF kinase inhibition was a turning point in the treatment of melanoma. But, as with other agents, resistance to treatment occurred and was mapped to the MAPK/ERK pathway. Primary resistance to vemurafenib in V600EBRAF melanomas can occur through increased cellular proliferation in response to loss of function of tumor suppressors or dysregulation of mechanisms that prevent apoptosis. PTEN deficiency is a major mechanism through which the prosurvival AKT signaling pathway becomes constitutively activated. This was observed in melanoma cell lines treated with vemurafenib. This PTEN deficiency was accompanied by loss of induction of the pro-apoptotic BIM/BCL2L11 protein, and resulted in primary resistance in these cell lines.48 Selective cytoplasmic redistribution of the transcription factor FOXO3a led to decreased transcription of pro-apoptotic proteins.49, 50 These findings, coupled with the fact that not every mutation-positive tumor will respond to B-RAF inhibitor therapy despite activating mutations in BRAF, underscores the need for future research into mechanisms of primary resistance.

Tumors with oncogenic driver mutations in the MAPK/ERK pathway have been observed to progress despite initial response to targeted intervention, secondary resistance. Multiple secondary mechanisms of resistance have been identified in melanoma, including new activating mutations in MAPK/ERK pathway genes 51 and NRAS 52, increased dimers of splice variants of wild type BRAF 33, 53, 54, amplification of wild type BRAF and MEK 55, and increased CRAF.56 New studies have demonstrated that C-RAF activates the MAPK/ERK pathway through acquisition of secondary mutations that increase its half-life, avoiding degradation, and allowing hetero-dimerization with B-RAF.57 Many of these mechanisms result in paradoxical hyperactivation of ERK.13 Intratumoral heterogeneity allows multiple mechanisms to be found within a single patient’s tumor, such as unique mutations in NRAS and an alternative splice variant of BRAF. 58 These findings support the concept that tumors demonstrate clonal evolution and plasticity over time, adapting to microenvironment and pharmacologic exposures.59

Colorectal Cancer

Targeted kinase inhibitors (KIs) that have been beneficial in melanoma have not yielded similar activity in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC). RAF signaling is downstream of RAS in the MAPK/ERK pathway, such that the presence of BRAF and KRAS mutations in CRC should lead to sensitivity to RAF-targeted agents and to circumvent inhibition of upstream signals, such as those emanating from receptor kinases. Consistent with that latter expectation, BRAF and KRAS mutations were demonstrated to be negative predictors of benefit to cetuximab and panitumumab, EGFR inhibitor therapy, in phase III clinical trials.60, 61 They did not predispose to susceptibility to inhibitor therapy as observed in melanoma. It is now routine clinical practice to test for KRAS mutation prior to initiation of EGFR inhibitors. Thus, rather than functioning as therapeutic targets in CRC, these genomic events in the MAPK/ERK pathway are validated negative predictive biomarkers for EGFR inhibitor intervention.

CRC resistance to B-RAF inhibition has been attributed to differential activation of EGFR in the cell membrane, reinforcing the differential relevance of EGFR expression across tumor types. Treatment of BRAF-mutant CRC cell lines with vemurafenib resulted in a strong increase in 1068Y-EGFR phosphorylation and receptor activation, through inhibition of CDC25C phosphatase that regulates 1068Y-EGFR phosphorylation. Blockade of MAPK/ERK by BRAF or MEK inhibitors prevented CDC25C activation resulting in increased 1068Y-EGFR and subsequent activation of other downstream pathways, such AKT. The combination of suppression of EGFR in combination with vemurafenib markedly inhibited proliferation in CRC cells and may be a mechanism to increase clinical activity. 62

Cross-communication between the MAPK/ERK pathway and parallel pathways, such as the PI3K-AKT and Wnt-Ca++ pathways, is critical to abnormal proliferation and therapy resistance. These parallel pathways are activated when the MAPK/ERK pathway is attenuated, and drive cellular proliferation. Inhibition of PI3K or AKT, or use of hypomethylating agents that secondarily block AKT signaling, can overcome this mechanism of resistance in vitro.63 Understanding of mechanisms of induction of parallel signaling is needed to guide development of combination therapies. Recently, Spreafico et al demonstrated a potential role of noncanonical Wnt/Ca++ signaling pathway in overcoming resistance of CRC to MEK inhibitors using cyclosporine (Wnt/Ca++ modulator) in a model of patient-derived tumor xenografts.64 These models demonstrated that drug combinations blocking both a targeted pathway and its associated counter-regulatory signal can effectively abrogate resistance of CRC to BRAF or MEK inhibitors.

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancers can be classified into distinct types, some of which are characterized by genetic mutations that may involve the MAPK/ERK pathway. Type II ovarian cancers include high-grade serous tumors, with defects in DNA repair via loss of normal p53 regulation in almost all tumors. 65,66 Type I ovarian tumors include low grade serous and endometrioid, clear cell, mucinous and borderline tumors (BOT); low grade serous cancers have mutations in KRAS (27-36%) and BRAF (33-50%), and in PIK3CA, whereas nearly all mucinous tumors may have KRAS mutations. 67-69 One study reported that 57% of BOT or low-grade serous tumors had V600BRAF or KRAS codon 12 mutations. Provocatively, patients with BRAF mutation had no recurrence after a median follow up of 3.6 years.70 Ho et al showed KRAS or BRAF mutations in 86% of cystadenomas adjacent to borderline tumors, and BOT had mutations in 88% of cases.71 There is a loss of frequency of BRAF and KRAS mutations in the transition from nonmalignant to malignant disease, from cystadenoma or BOT to invasive low grade serous cancer. The mechanism of this selective process by which there is loss of an otherwise recognized oncogenic mutation during the process of acquisition of an invasive phenotype is unknown. This is the only example identified where there is such loss of a perceived gain-of-function mutation.

The identification of these mutations led to the logical hypothesis that such ovarian neoplasms were a new frontier for experimentation with targeted BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapy. Gynecologic Oncology Group study 239, a phase II trial of the MEK inhibitor, selumetinib, in 52 previously treated patients with low grade serous ovarian tumors yielded a 15% overall response rate and a median progression free survival of 11 months. This was compared to a historical PFS of 7 months. Mutational analysis was performed in tumor from 34 patients; KRAS and BRAF mutations were found in 41% and 6%, respectively, although mutation did not correlate with response or longer PFS.72 These examples argue against a preponderant role of the MAPK/ERK pathway as a targeting oncogenic driver in these tumors, despite the presence of mutations. Studies of sorafenib in predominantly high serous histology recurrent ovarian cancer patients did not demonstrate biochemical activity of reduced ERK activation pre and on-treatment, perhaps consistent with the lack of genomic events in the MAPK/ERK pathway in those tumors.73

Interactions between the MAPK/ERK pathway and estrogen receptor-α (ERα) have also been identified in preclinical studies. MEK inhibition caused an increase in ERα expression independent of AKT signaling in ovarian cell lines positive for ERα. The addition of the ER inhibitor fulvestrant caused synergistic suppression of tumor growth in vitro and in an in vivo model.74 This may be a direction for clinical study using modulation of the MAPK/ERK pathway to secondarily regulate a parallel pathway. This reinforces how ovarian cancer is a challenging environment in which to study the tumor specific effects of MAPK/ERK pathway activation. Its broad range of cellular diversity and complexity of pathways activation lends itself to combination therapy, necessitating greater understanding of the interaction of the pathways.

Conclusion

The downstream MAPK/ERK signaling node, predominantly activated by upstream SRC/RAS/RAF signaling, is also regulated by modulation through parallel pathways. This creates a complexity within and between tumors that impedes the ability to translate therapeutic findings across tumors. Tissue and subtype specificity in signaling adds a level of complexity to application of novel targeted agents, even against an otherwise dominant pathway. The MAPK/ERK pathway stimulates cellular proliferation and invasion; however, its activation also can increase cellular apoptosis or antagonize pro-oncogenic input from other signals. The MAPK/ERK pathway demonstrates both oncogene and tumor suppressor effects depending on the tissue-specific tumor microenvironment. While cancers share common mutations, different cell types have developed unique responses to the mutations. These mutations may behave as oncogenic drivers, passenger mutations, or regulatory events. The role of the MAPK/ERK pathway in the tumor microenvironment has long been recognized. This pathway is critical in the process of physiologic and malignant invasion, angiogenesis, and most recently, a clear role for MAPK/ERK has been demonstrated in the tumor-immune system interactions. Hence, MAPK/ERK activation is a multi-faceted target under varied regulatory bodies. Regulatory mechanisms may lead to activation of alternative pathways, and paradoxical hyperactivation of the normal MAPK/ERK pathway. One unintended and unexpected consequence of KRAS/BRAF inhibitor drug therapy is increased activity of the normal MAPK/ERK pathway, which can lead to the development of secondary malignancies. Some novel combination therapies have demonstrated increased treatment efficacy by addressing both a specific target and its counter-regulatory effect in the complex milieu of cellular signaling. In shaping future approaches toward personalized medicine, the challenge is clear: we must strike a delicate balance between exploiting shared genetic targets and acknowledging unique features of human cancers.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: No financial disclosures

References

- 1.Hudson TJ, Anderson W, Artez A, et al. International network of cancer genome projects. Nature. 2010;464(7291):993–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciriello G, Miller ML, Aksoy BA, Senbabaoglu Y, Schultz N, Sander C. Emerging landscape of oncogenic signatures across human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45(10):1127–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstein IB, Joe A. Oncogene addiction. Cancer Res. 2008;68(9):3077–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3293. discussion 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Luca A, Maiello MR, D’Alessio A, Pergameno M, Normanno N. The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and the PI3K/AKT signalling pathways: role in cancer pathogenesis and implications for therapeutic approaches. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(Suppl 2):S17–27. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.639361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang SH, Sharrocks AD, Whitmarsh AJ. MAP kinase signalling cascades and transcriptional regulation. Gene. 2013;513(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Jr., Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339(6127):1546–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tebbutt N, Pedersen MW, Johns TG. Targeting the ERBB family in cancer: couples therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(9):663–73. doi: 10.1038/nrc3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):459–65. doi: 10.1038/nrc1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muram-Zborovski TM, Stevenson DA, Viskochil DH, Dries DC, Wilson AR, Rong M. SPRED 1 mutations in a neurofibromatosis clinic. J Child Neurol. 2010;25(10):1203–9. doi: 10.1177/0883073809359540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wan PT, Garnett MJ, Roe SM, et al. Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell. 2004;116(6):855–67. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farooq A, Zhou MM. Structure and regulation of MAPK phosphatases. Cell Signal. 2004;16(7):769–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cossa G, Gatti L, Cassinelli G, Lanzi C, Zaffaroni N, Perego P. Modulation of sensitivity to antitumor agents by targeting the MAPK survival pathway. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(5):883–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhanasekaran N, Premkumar Reddy E. Signaling by dual specificity kinases. Oncogene. 1998;17(11 Reviews):1447–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson MJ, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9(2):180–6. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pullikuth AK, Catling AD. Scaffold mediated regulation of MAPK signaling and cytoskeletal dynamics: a perspective. Cell Signal. 2007;19(8):1621–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pandolfi PP. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2005;121(2):179–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu B, Soncin F, Price BD, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. Sequential phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase and glycogen synthase kinase 3 represses transcriptional activation by heat shock factor-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(48):30847–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmid RS, Pruitt WM, Maness PF. A MAP kinase-signaling pathway mediates neurite outgrowth on L1 and requires Src-dependent endocytosis. J Neurosci. 2000;20(11):4177–88. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04177.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf I, Rubinfeld H, Yoon S, Marmor G, Hanoch T, Seger R. Involvement of the activation loop of ERK in the detachment from cytosolic anchoring. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(27):24490–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zassadowski F, Rochette-Egly C, Chomienne C, Cassinat B. Regulation of the transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors by the MEK/ERK1/2 pathway. Cell Signal. 2012;24(12):2369–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sigoillot FD, Evans DR, Guy HI. Growth-dependent regulation of mammalian pyrimidine biosynthesis by the protein kinase A and MAPK signaling cascades. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(18):15745–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arthur JS, Ley SC. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(9):679–92. doi: 10.1038/nri3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winters ME, Mehta AI, Petricoin EF, 3rd, Kohn EC, Liotta LA. Supra-additive growth inhibition by a celecoxib analogue and carboxyamido-triazole is primarily mediated through apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65(9):3853–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy LO, Smith S, Chen RH, Fingar DC, Blenis J. Molecular interpretation of ERK signal duration by immediate early gene products. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(8):556–64. doi: 10.1038/ncb822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy T, Hori S, Sewell J, Gnanapragasam VJ. Expression and functional role of negative signalling regulators in tumour development and progression. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(11):2491–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz M, Amit I, Yarden Y. Regulation of MAPKs by growth factors and receptor tyrosine kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773(8):1161–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deschenes-Simard X, Gaumont-Leclerc MF, Bourdeau V, et al. Tumor suppressor activity of the ERK/MAPK pathway by promoting selective protein degradation. Genes Dev. 2013;27(8):900–15. doi: 10.1101/gad.203984.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88(5):593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bric A, Miething C, Bialucha CU, et al. Functional identification of tumor-suppressor genes through an in vivo RNA interference screen in a mouse lymphoma model. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(4):324–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts PJ, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26(22):3291–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bedard PL, Hansen AR, Ratain MJ, Siu LL. Tumour heterogeneity in the clinic. Nature. 2013;501(7467):355–64. doi: 10.1038/nature12627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, Shokat KM, Rosen N. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010;464(7287):427–30. doi: 10.1038/nature08902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solit DB, Garraway LA, Pratilas CA, et al. BRAF mutation predicts sensitivity to MEK inhibition. Nature. 2006;439(7074):358–62. doi: 10.1038/nature04304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bollag G, Hirth P, Tsai J, et al. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature. 2010;467(7315):596–9. doi: 10.1038/nature09454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boni A, Cogdill AP, Dang P, et al. Selective BRAFV600E inhibition enhances T-cell recognition of melanoma without affecting lymphocyte function. Cancer Res. 2010;70(13):5213–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bekaii-Saab T, Phelps MA, Li X, et al. Multi-institutional phase II study of selumetinib in patients with metastatic biliary cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2357–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.9473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho AL, Grewal RK, Leboeuf R, et al. Selumetinib-enhanced radioiodine uptake in advanced thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(7):623–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janne PA, Shaw AT, Pereira JR, et al. Selumetinib plus docetaxel for KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(8):707–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):358–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60868-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vin H, Ching G, Ojeda SS, et al. Sorafenib Suppresses JNK-Dependent Apoptosis through Inhibition of ZAK. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(1):221–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(18):1694–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Trametinib and Dabrafenib approbal. 2014.

- 45.Thomas RK, Baker AC, Debiasi RM, et al. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39(3):347–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(21):2129–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA, et al. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med. 2005;2(3):e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paraiso KH, Xiang Y, Rebecca VW, et al. PTEN loss confers BRAF inhibitor resistance to melanoma cells through the suppression of BIM expression. Cancer Res. 2011;71(7):2750–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang JY, Hung MC. A new fork for clinical application: targeting forkhead transcription factors in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(3):752–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fedorenko IV, Paraiso KH, Smalley KS. Acquired and intrinsic BRAF inhibitor resistance in BRAF V600E mutant melanoma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82(3):201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Daouti S, Li WH, et al. Identification of the MEK1(F129L) activating mutation as a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to MEK inhibition in human cancers carrying the BRafV600E mutation. Cancer Res. 2011;71(16):5535–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Montagut C, Sharma SV, Shioda T, et al. Elevated CRAF as a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to BRAF inhibition in melanoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68(12):4853–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roskoski R., Jr RAF protein-serine/threonine kinases: structure and regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399(3):313–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poulikakos PI, Persaud Y, Janakiraman M, et al. RAF inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly spliced BRAF(V600E) Nature. 2011;480(7377):387–90. doi: 10.1038/nature10662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corcoran RB, Dias-Santagata D, Bergethon K, Iafrate AJ, Settleman J, Engelman JA. BRAF gene amplification can promote acquired resistance to MEK inhibitors in cancer cells harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Sci Signal. 2010;3(149):ra84. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosell R, Bivona TG, Karachaliou N. Genetics and biomarkers in personalisation of lung cancer treatment. Lancet. 2013;382(9893):720–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Antony R, Emery CM, Sawyer AM, Garraway LA. C-RAF mutations confer resistance to RAF inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2013;73(15):4840–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Romano E, Pradervand S, Paillusson A, et al. Identification of Multiple Mechanisms of Resistance to Vemurafenib in a Patient with BRAFV600E-Mutated Cutaneous Melanoma Successfully Rechallenged after Progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meacham CE, Morrison SJ. Tumour heterogeneity and cancer cell plasticity. Nature. 2013;501(7467):328–37. doi: 10.1038/nature12624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, et al. Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(35):5705–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richman SD, Seymour MT, Chambers P, et al. KRAS and BRAF mutations in advanced colorectal cancer are associated with poor prognosis but do not preclude benefit from oxaliplatin or irinotecan: results from the MRC FOCUS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):5931–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483(7387):100–3. doi: 10.1038/nature10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mao M, Tian F, Mariadason JM, et al. Resistance to BRAF inhibition in BRAF-mutant colon cancer can be overcome with PI3K inhibition or demethylating agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(3):657–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spreafico A, Tentler JJ, Pitts TM, et al. Rational combination of a MEK inhibitor, selumetinib, and the Wnt/calcium pathway modulator, cyclosporin A, in preclinical models of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(15):4149–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kohn EC, Romano S, Lee JM. Clinical implications of using molecular diagnostics for ovarian cancers. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(Suppl 10):x22–26. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee JM, Ledermann JA, Kohn EC. PARP Inhibitors for BRCA1/2 mutation-associated and BRCA-like malignancies. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(1):32–40. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shih Ie M, Kurman RJ. Ovarian tumorigenesis: a proposed model based on morphological and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(5):1511–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63708-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bell DA. Origins and molecular pathology of ovarian cancer. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(Suppl 2):S19–32. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singer G, Oldt R, 3rd, Cohen Y, et al. Mutations in BRAF and KRAS characterize the development of low-grade ovarian serous carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(6):484–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grisham RN, Iyer G, Garg K, et al. BRAF mutation is associated with early stage disease and improved outcome in patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(3):548–54. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ho CL, Kurman RJ, Dehari R, Wang TL, Shih Ie M. Mutations of BRAF and KRAS precede the development of ovarian serous borderline tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64(19):6915–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Farley J, Brady WE, Vathipadiekal V, et al. Selumetinib in women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(2):134–40. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70572-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matei D, Sill MW, Lankes HA, et al. Activity of sorafenib in recurrent ovarian cancer and primary peritoneal carcinomatosis: a gynecologic oncology group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(1):69–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hou JY, Rodriguez-Gabin A, Samaweera L, et al. Exploiting MEK inhibitor-mediated activation of ERalpha for therapeutic intervention in ER-positive ovarian carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e54103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Colombino M, Capone M, Lissia A, et al. BRAF/NRAS mutation frequencies among primary tumors and metastases in patients with melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2522–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Edlundh-Rose E, Egyhazi S, Omholt K, et al. NRAS and BRAF mutations in melanoma tumours in relation to clinical characteristics: a study based on mutation screening by pyrosequencing. Melanoma Res. 2006;16(6):471–8. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000232300.22032.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417(6892):949–54. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Murugan AK, Dong J, Xie J, Xing M. MEK1 mutations, but not ERK2 mutations, occur in melanomas and colon carcinomas, but none in thyroid carcinomas. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(13):2122–4. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.13.8710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nikolaev SI, Rimoldi D, Iseli C, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic MAP2K1 and MAP2K2 mutations in melanoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44(2):133–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seo JS, Ju YS, Lee WC, et al. The transcriptional landscape and mutational profile of lung adenocarcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22(11):2109–19. doi: 10.1101/gr.145144.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cardarella S, Ogino A, Nishino M, et al. Clinical, pathologic, and biologic features associated with BRAF mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(16):4532–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tol J, Nagtegaal ID, Punt CJ. BRAF mutation in metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):98–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0904160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sieben NL, Macropoulos P, Roemen GM, et al. In ovarian neoplasms, BRAF, but not KRAS, mutations are restricted to low-grade serous tumours. J Pathol. 2004;202(3):336–40. doi: 10.1002/path.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bansal M, Gandhi M, Ferris RL, et al. Molecular and histopathologic characteristics of multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(10):1586–91. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318292b780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xing M, Alzahrani AS, Carson KA, et al. Association between BRAF V600E mutation and mortality in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. JAMA. 2013;309(14):1493–501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cohen Y, Xing M, Mambo E, et al. BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(8):625–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.8.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xi L, Arons E, Navarro W, et al. Both variant and IGHV4-34-expressing hairy cell leukemia lack the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood. 2012;119(14):3330–2. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tiacci E, Trifonov V, Schiavoni G, et al. BRAF mutations in hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(24):2305–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Turke AB, Zejnullahu K, Wu YL, et al. Preexistence and clonal selection of MET amplification in EGFR mutant NSCLC. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(1):77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ng KP, Hillmer AM, Chuah CT, et al. A common BIM deletion polymorphism mediates intrinsic resistance and inferior responses to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer. Nat Med. 2012;18(4):521–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nakagawa T, Takeuchi S, Yamada T, et al. EGFR-TKI resistance due to BIM polymorphism can be circumvented in combination with HDAC inhibition. Cancer Res. 2013;73(8):2428–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(8):786–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(75):75ra26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Takezawa K, Pirazzoli V, Arcila ME, et al. HER2 amplification: a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to EGFR inhibition in EGFR-mutant lung cancers that lack the second-site EGFRT790M mutation. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(10):922–33. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316(5827):1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Whittaker SR, Theurillat JP, Van Allen E, et al. A genome-scale RNA interference screen implicates NF1 loss in resistance to RAF inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(3):350–62. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maertens O, Johnson B, Hollstein P, et al. Elucidating distinct roles for NF1 in melanomagenesis. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(3):338–49. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Atefi M, von Euw E, Attar N, et al. Reversing melanoma cross-resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors by co-targeting the AKT/mTOR pathway. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Corcoran RB, Ebi H, Turke AB, et al. EGFR-mediated re-activation of MAPK signaling contributes to insensitivity of BRAF mutant colorectal cancers to RAF inhibition with vemurafenib. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(3):227–35. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sheppard KE, Cullinane C, Hannan KM, et al. Synergistic inhibition of ovarian cancer cell growth by combining selective PI3K/mTOR and RAS/ERK pathway inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]