Abstract

Reverse phase HPLC coupled to negative mode electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry (MS) was used to quantify 16 flavonoids and 2 phenolic acids from almond skin extracts. Calibration curves of standard compounds were run daily and daidzein was used as an internal standard. The inter-day relative standard deviation (RSD) of standard curve slopes ranged from 13% to 25% of the mean. On column (OC) limits of detection (LOD) for polyphenols ranged from 0.013 to 1.4 pmol, and flavonoid glycosides had a 7-fold greater sensitivity than aglycones. Limits of quantification were 0.043 to 2.7 pmol OC, with a mean of 0.58 pmol flavonoid OC. Mean inter-day RSD of polyphenols in almond skin extract was 6.8% with a range of 4% to 11%, and intra-day RSD was 2.4%. Liquid nitrogen (LN2) or hot water (HW) blanching was used to facilitate removal of the almond skins prior to extraction using assisted solvent extraction (ASE) or steeping with acidified aqueous methanol. Recovery of polyphenols was greatest in HW blanched almond extracts with a mean value of 2.1 mg/g skin. ASE and steeping extracted equivalent polyphenols, although ASE of LN2 blanched skins yielded 52% more aglycones and 23% less flavonoid glycosides. However, the extraction methods did not alter flavonoid profile of HW blanched almond skins. The recovery of polyphenolic components that were spiked into almond skins before the steeping extraction was 97% on a mass basis. This LC-MS method presents a reliable means of quantifying almond polyphenols.

Keywords: almond, flavonoid, LC-MS, polyphenols, quantification

Introduction

Tree nuts, including almonds, are advocated as health-promoting foods (King and others 2008). Health promotion derived from the antioxidant properties of almonds has been demonstrated in several nutritional intervention trials. For example, almond supplementation enhanced antioxidant defenses and reduced biomarkers of oxidative stress in smokers (Li and others 2007). Almond consumption decreased lipid peroxidation in hyperlipidemic men (Jenkins and others 2008). While almonds are an excellent source of the antioxidant vitamin E, the polyphenols in almonds skins may also contribute to their antioxidant capacity and health-promoting actions (Chen and others 2005; Milbury and others 2006; Chen and Blumberg 2008).

Almond polyphenols are a mixture of phenolic acids, flavonoids, and tannins that contribute to the antioxidant capacity of almonds in an additive or even synergistic manner (Milbury and others 2006; Garrido and others 2008). Thus, reliable and accurate quantification of almond polyphenols is important to estimate their contribution to dietary intakes, particularly because the polyphenolic content and antioxidant activity of almonds is dependent on the cultivar (Milbury and others 2006; Barriera and others 2008). Improved routine quantitative measures for these polyphenols can also provide more accurate information for nutrient databases and be helpful for distinguishing optimal harvesting, processing, and storage parameters to promote or maintain these almond phytochemicals.

Liquid chromatography-electrochemical detection (LC-ECD), capillary liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), and LC-MS identification coupled with UV analysis have been employed to quantify almond polyphenols. However, for this purpose, these methods are limited in applicability and specificity. An LC-ECD method based on redox potential required 2 h of analysis, which is not suitable for high-throughput analysis (Milbury and others 2006). Garrido and others (2008) also measured almond polyphenols by a 2-h LC method and quantified flavonoids through UV and fluorescence detection. Similarly, Prodanov and others (2008) utilized LC-MS for polyphenol identification coupled with UV analysis and further analyzed high-molecular-weight polyphenols such as proanthocyanidins oligomers. A capillary LC-MS method decreased the time and sample volume requirement of previous LC methods, but required specialized equipment not available in most analytical laboratories (Milbury and others 2006; Hughey and others 2008).

The objective of the present study was to develop a routine, conventional, noncapillary LC-MS method for quantifying almond skin polyphenols. Previous almond polyphenol extraction methods have included different procedures, including blanching, steeping, sonication, and solvent-assisted extraction (Milbury and others 2006; Chen and Blumberg 2008; Hughey and others 2008). Therefore, determining reproducibility and accuracy of polyphenol extraction methods was a secondary objective.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, quercetin-3-O-galactoside, isorhamnetin, kampferol-3-O-rutinoside, kaempferol-3-O-glucoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside, and naringenin-7-O-glucoside were from Extrasynthese (Genay, France). Naringenin, quercetin, eriodictyol, and daidzein were from Indofine (Belle Mead, N.J., U.S.A.). (+)-Catechin, protocatechuc acid, (−)-epicatechin, kaempferol, formic acid, and acetic acid were from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo., U.S.A.). Methanol was high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade from Fischer (Fair Lawn, N.J., U.S.A.). Water was ultrapure grade.

Extraction and sample preparation

Raw Nonpareil and butte almond samples were provided by the Almond Board of California. Whole almonds were immersed in liquid nitrogen (LN2) for 10 min and thawed to room temperature or cooler by incubating at 60 °C for 10 min. The freeze thaw cycle was repeated 3 times and almond skins were hand peeled, pulverized using a mortar and pestle under LN2, and stored at −80 °C in darkness until extraction.

To compare the results of this study to our previous work, almond skins were also removed using a method of hot water blanching (HW) (Milbury and others 2006). Aliquots of the blanch water were immediately frozen at − 20 °C and thawed before analysis. Blanched almond skins were air-dried at room temperature for approximately 24 h, powdered under LN2, and stored at −80 °C until extraction.

Polyphenols in almond skin powder were extracted using assisted solvent extraction (ASE) or steeping. Using our previous method, ASE was performed by mixing 0.2 mg aliquots with 5 parts diatomaceous earth, and sequentially extracting at 100 °C and 1500 psi with 90%, 60%, and 30% aqueous methanol in 5% acetic acid for 3 cycles of 15 min each (Accelerated Solvent Extraction System 200, Dionex, Sunnyale, Calif., U.S.A.) (Chen and Blumberg 2008). For steeping extraction, 0.2 g aliquots of pulverized almond skin were placed in glass screw-capped amber vials with 5 mL 3.5% acetic acid in 50% aqueous methanol. Extraction vessels were agitated at 4 °C on a Speci-mix rocker (Thermolyne, Dubuque, Iowa, U.S.A.) for 8 h. Vessels were then centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was removed and the pellet was resuspended in 5 mL of the extraction solvent and similarly agitated for an additional 10 h. After centrifugation, the supernatants were combined and 500 μL aliquots of extracts from both extraction methods were dried under nitrogen gas in microcentrifuge tubes. Dry matter was stored at −20 °C in darkness, for less than 2 mo until analysis. On the days of LC-MS analysis, samples were resuspended in 497 μL 50% methanol and 3 μL of 1 mM daidzein as an internal standard, diluted 10-fold in 1% formic acid, and centrifuged at 12000 × g for 10 min to pellet any residue.

The polyphenol recovery of the steeping method was estimated by spiking standards in 0.2 mg of almond skin samples, 0.2 mg cellulose or the extraction solvent only. Spiked concentrations were equivalent to those obtained from the acidified aqueous methanol extraction of an almond skin sample.

LC-MS conditions

An Agilent 1100 MSD quadrupole, with electrospray ionization (ESI) was fitted with a 250 × 4.60 mm Synergi 4u MAX-RP 80A column (Phenomenex, Torrance, Calif., U.S.A.) set to a constant temperature of 25 °C. Mobile phase A consisted of formic acid (1%) in ultrapure water and mobile phase B was 100% methanol. Following a 30-μL injection of appropriately diluted samples, a gradient of 50% to 100% B was run from 0 to 20 min, and then held at 100% B for 10 min, decreased to 50% B in 5 min and held for another 15 min for a total run time of 50 min at 0.2 mL/min. For detection, capillary current was set at 16 nA with a quadrupole temperature at 100 °C. MSD signals were acquired in selection ion monitoring mode in 3 groups as negative ions: m/z 137, 153, and 289 from retention time (Rt) of 0 to 22.6 min; m/z 137, 287, 433, 447, 463, 477, 593, 609, and 623 from Rt 22.6 to 28.2 min; and m/z 253, 271, 285, 287, 301, and 315 from Rt 28.2 to 50 min. The fragmentor was set at 100 V and detector gain was 15.

Prior to calibration curve runs, all standards were mixed in a stock solution of methanol, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C in amber screw-capped glass vials. On each day of analysis, different concentrations of standard solutions were serially diluted with 1% aqueous formic acid. The final starting concentrations of standards (μg/mL) were: (+)-catechin (6.50), (−)-epicatechin (3.80), daidzein (1.50), eriodictyol (0.500), p-hyroxybenzoic acid (1), isorhamnetin (0.600), isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside (1.00), isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside (12.0), kaempferol (0.250), kaempferol-3-glucoside (2.00), kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside (6.14), naringenin (2.60), naringenin-7-glucoside (3.50), protocatechuic acid (2.10), quercetin (0.180), quercetin-3-galactoside (0.200), and rutin (0.500).

Limits of detection (LOD) and limits of quantification (LOQ)

Signal (S) to noise (N) ratios were calculated by the area under the curve (AUC) values of standards. The LODs (S/N > 3) and LOQs (S/N > 10) were determined by at least 3 injections of serial dilutions of the calibration curve, where S/N = (SDAUC/AUC) (Long and Winefordner 1983).

Statistical analysis

Raw data or a logarithmic transform of data with unequal variation were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When P was ≤0.05, significance was by Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.01, La Jolla, Calif., U.S.A.). Relative standard deviation (RSD) was defined as: SD/mean × 100%.

Results and Discussion

Chromatography

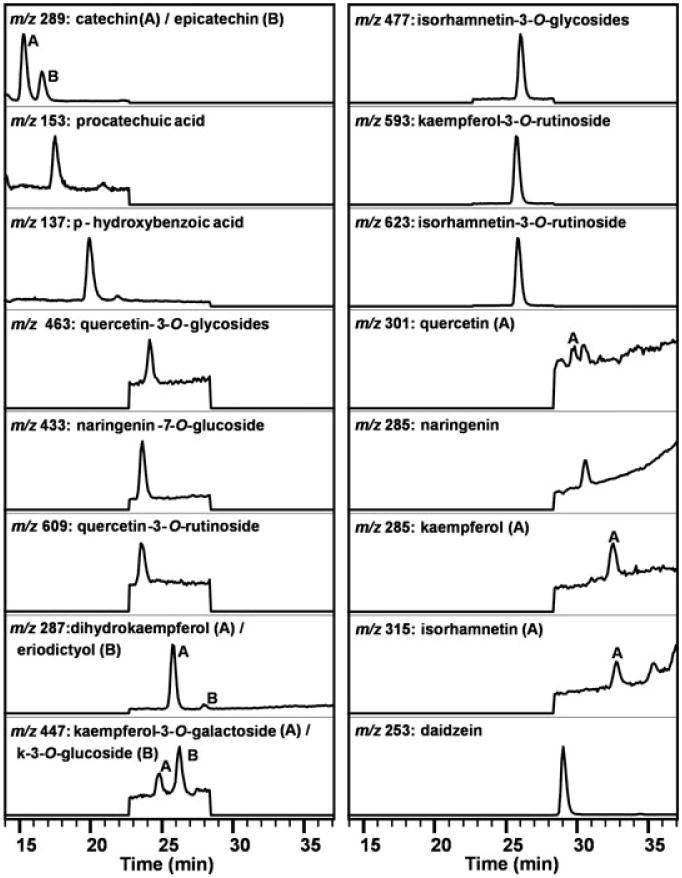

The LC-MS method described here reduced the analysis time for almond skin polyphenols to 50 min from the 120 min required by our reported LC-ECD method (Milbury and others 2006). Phenolic acids and flavonoids characterized in the present study eluted from Rt 15 to 32 min (Figure 1, Table 1), whereas our previous method these eluted from Rt 21 to 90 min. While the present method is longer than the 11 min achieved by a capillary LC-MS method for quantification of almond skin flavonoids (Hughey and others 2008), after our analysis time is similar to other reported methods of LC-MS flavonoid quantification in strawberry and spinach (Seeram and others 2006; Cho and others 2008). Thus, the present method accomplishes quantification of almond skin polyphenols in less than half the time of the LC-ECD method and with comparable time to other methods of flavonoid analysis.

Figure 1. LC-MS chromatogram of Nonpareil almond skin extract from 14 to 37 min.

Table 1. Retention times, standard curve slopes and RSD, inter-day RSD, and intra-day RSD for an LC-MS method of analysis for almond skin polyphenols.

| Peak, polyphenols | Mol. ion [M-H]− | Rt (min) | Mean slope (n = 18) | Standard slope % RSD | Inter-day % RSD (n = 7) | Intra-day % RSD (n = 3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (+)-catechin | 289 | 15.21 | 4.05E + 06 | 16 | 10.3 | 2.4 |

| (2) | (−)-epicatechin | 289 | 16.46 | 5.08E + 06 | 15 | 10.6 | 2.7 |

| (3) | procatechuic acid | 153 | 17.37 | 3.68E + 06 | 13 | 7.1 | 1.3 |

| (4) | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | 137 | 21.67 | 4.38E + 06 | 15 | 5.1 | 5.8 |

| (5) | quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | 609 | 23.30 | 1.04E + 07 | 15 | 4.1 | 2.6 |

| (6) | naringenin-7-O-glucoside | 433 | 23.40 | 7.55E + 06 | 14 | 5.2 | 1.4 |

| (7) | quercetin-3-O-galactosidea | 463 | 23.88 | 1.23E + 07 | 16 | 5.2 | 2.5 |

| (8) | kaempferol-3-O-galactosideb | 447 | 24.20 | NAc | NA | 4.3 | 3.4 |

| (9) | kaempferol-3-O-rutinioside | 593 | 24.52 | 1.64E + 07 | 15 | 5.7 | 2.0 |

| (10) | dihydrokaempferold | 287 | 25.49 | NA | NA | 8.1 | 1.2 |

| (11) | isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside | 623 | 25.51 | 1.07E + 07 | 15 | 5.8 | 1.4 |

| (12) | isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | 477 | 25.60 | 1.69E + 07 | 14 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| (13) | kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | 447 | 25.67 | 9.86E + 06 | 18 | 6.3 | 2.4 |

| (14) | eriodictyol | 287 | 25.81 | 1.17E + 07 | 17 | 5.6 | 3.0 |

| daidzein (internal standard) | 253 | 27.71 | 3.81E + 06 | 16 | 7.4 | 3.8 | |

| (15) | quercetin | 301 | 30.26 | 1.07E + 07 | 25 | 5.0 | 1.3 |

| (16) | naringenin | 271 | 30.33 | 7.37E + 06 | 14 | 10.5 | 2.3 |

| (17) | kaempferol | 285 | 32.27 | 2.44E + 07 | 20 | 9.9 | 2.8 |

| (18) | isorhamnetin | 315 | 32.53 | 3.17E + 07 | 19 | 6.8 | 2.4 |

| Average | 16 | 6.8 | 2.4 | ||||

Quercetin-3-O-galctoside was not resolved from quercetin-3-O-glucoside.

Kaempferol-3-O-glactoside concentration was determined on the basis of kaempferol-3-O-glucoside equivalents.

NA = not applicable.

Dihydrokaempferol was quantified on the basis of eriodictyol equivalents.

The ESI conditions employed in this study for analysis of flavonoid glycosides and aglycone did not sufficiently ionize vanillic acid. Therefore, vanillic acid was not quantified, although it was detected in almond skin extracts by our previous ECD method (Milbury and others 2006). Further, this LC-MS method was unable to resolve isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside from isorhamnetin-3-O-galactoside and quercetin-3-O-galactoside from quercetin-3-O-glucoside, even though our previous LC-ECD method was able to resolve these glycosides (Milbury and others 2006). Similarly, isorhamnetin and kaempferol glycosides in almond skins were not resolved by capillary LC-MS (Hughey and others 2008). Although it may be desirable in some cases to achieve resolution of these compounds, they were quantified here as sum of glycosides to reduce the time for analysis. Thus, this method readily provides key composition data by resolving 18 almond skin polyphenols.

Method reproducibility

Calibration curves were run daily to correct for instrument variability. Over a course of 18 d, the analysis duration in this study, the inter-day RSD of standard curve slopes ranged from 13% to 25% (Table 1). However, after the adjustment for instrument variation with an internal standard daidzein, the average inter-day RSD for 18 polyphenols in a control almond sample was decreased to 6.8% with a range of 4% to 11% (n = 7) (Table 2). The intra-day RSD average was 2.4%, and ranged from 1% to 6%. Variation of the present method was similar to the range of 2% to 11% for inter-assay and 1% to 5% for intra-assay RSD reported using an HPLC-ECD method (Milbury and others 2006) and 6% intra-assay RSD reported using capillary LC-MS (Hughey and others 2008) for quantifying almond skin polyphenolics.

Table 2. Limits of detection (LOD) and limits of quantification (LOQ) for a 30-μL injection of standard compounds using an LC-MS method of analysis for almond skin polyphenols.

| Peak, polyphenols | LOD (n = 3) | LOQ (n = 3) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| nM | ng/mL | pmol OCa | pg OC | nM | ng/mL | pmol OC | pg OC | ||

| (1) | (+)-catechin | 1.1 | 0.32 | 0.033 | 9.6 | 44 | 13 | 1.3 | 380 |

| (2) | (−)-epicatechin | 1.3 | 0.38 | 0.039 | 11 | 6.5 | 1.9 | 0.19 | 57 |

| (3) | procatechuic acid | 6.8 | 1.1 | 0.20 | 32 | 68 | 11 | 2.0 | 320 |

| (4) | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | 13 | 2.0 | 0.38 | 60 | 31 | 5.0 | 0.94 | 150 |

| (5) | quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | 0.8 | 0.50 | 0.025 | 15 | 4.1 | 2.5 | 0.12 | 75 |

| (6) | naringenin-7-O-glucoside | 1.6 | 0.70 | 0.048 | 21 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 0.12 | 53 |

| (7) | quercetin-3-O-galactoside | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.017 | 12 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.043 | 30 |

| (9) | kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.015 | 9.2 | 5.2 | 3.1 | 0.15 | 92 |

| (11) | isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside | 1.0 | 0.60 | 0.029 | 18 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 0.11 | 72 |

| (12) | isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.013 | 6.0 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 0.13 | 60 |

| (13) | kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.067 | 30 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 0.27 | 120 |

| (14) | eriodictyol | 3.5 | 1.0 | 0.10 | 30 | 8.7 | 2.5 | 0.26 | 75 |

| (15) | quercetin | 3.0 | 0.90 | 0.089 | 27 | 6.0 | 1.8 | 0.18 | 54 |

| (16) | naringenin | 48 | 13 | 1.4 | 390 | 96 | 26 | 2.7 | 780 |

| (17) | kaempferol | 4.4 | 1.3 | 0.13 | 38 | 8.7 | 2.5 | 0.26 | 75 |

| (18) | isorhamnetin | 3.8 | 1.2 | 0.11 | 36 | 9.5 | 30 | 0.28 | 90 |

| Average | 5.7 | 1.6 | 0.17 | 47 | 19 | 5.2 | 0.58 | 160 | |

OC = on column.

Method sensitivity

On column (OC) LOD for polyphenols ranged from 0.013 to 1.4 pmol (Table 3). Flavonoid glycosides were detected with 9-fold greater sensitivity than aglycones on average, with mean OC of 0.031 and 0.27 pmol, respectively. The LOQ for determination of almond skin polyphenols ranged from 0.043 to 2.7 pmol OC, and with a mean of 0.58 pmol. The average 47 pg LOD of almond skin polyphenols was similar to the 60 pg LOD achieved by capillary LC-MS (Hughey and others 2008). Not all compounds had sensitivity similar to the capillary method. The present method had 20-fold greater sensitivity for isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside and 13-fold less sensitivity for naringenin compared to capillary LC-MS (Hughey and others 2008). Further, other methods of analysis exceed our LOQ for flavonols. Quercetin, kaempferol, and isorhamnetin measured in plasma following administration of Ginko biloba had lower OC LOQ of 1.3, 1.3, and 0.4 pg, respectively, as reported by Zhao and others (2007). Nonetheless, the polyphenol LOQ of the present LC-MS method appears sufficient for routine analysis of almond polyphenols.

Table 3. Quantification of almond skin polyphenols from raw almonds and comparison of extraction and blanching methods (n = 3).

| Peak, polyphenols (μg/g) | Methanol steeping 24 h | Assisted solvent extraction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Liquid N2 | Hot water | Liquid N2 | Hot water | ||

| (1) | (+)-catechin | 157.93 | 331.22 (66)a | 345.22 | 366.26 (63) |

| (2) | −)-epicatechin | 94.88 | 232.01 (74) | 145.90 | 266.08 (69) |

| (3) | procatechuic acid | 12.88 | 41.52 (65) | 39.34 | 61.92 (49) |

| (4) | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | 3.97 | 9.37 (76) | 8.38 | 12.30 (58) |

| (5) | quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | 12.64 | 16.59 (80) | 10.30 | 16.22 (80) |

| (6) | naringenin-7-O-glucoside | 30.40 | 49.31 (72) | 36.94 | 58.84 (62) |

| (7) | quercetin-3-O-galactoside | 9.91 | 13.64 (73) | 8.80 | 13.69 (74) |

| (8) | bkaempferol-3-O-galactoside | 7.24 | 19.90 (65) | 14.16 | 21.69 (60) |

| (9) | kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside | 151.92 | 232.52 (83) | 130.30 | 219.64 (84) |

| (10) | cdihydrokaempferol | 71.84 | 97.89 (85) | 53.31 | 97.06 (86) |

| (11) | isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside | 538.23 | 741.36 (77) | 416.82 | 717.63 (79) |

| (12) | isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | 149.27 | 145.39 (75) | 88.83 | 147.03 (76) |

| (13) | kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | 26.74 | 37.39 (73) | 28.98 | 37.71 (73) |

| (14) | eriodictyol | 4.53 | 4.60 (70) | 3.01 | 4.35 (75) |

| (15) | quercetin | 1.73 | 1.04 (78) | 0.01 | 1.25 (65) |

| (16) | naringenin | 97.04 | 97.36 (76) | 65.71 | 94.70 (78) |

| (17) | kaempferol | 3.72 | 4.86 (65) | 3.66 | 4.36 (64) |

| (18) | isorhamnetin | 13.31 | 32.00 (53) | 13.10 | 13.72 (75) |

| Sum of polyphenols | 1388.17 | 2107.96 (75) | 1412.76 | 2154.47 (73) | |

Percentage of component recovered in the residual blanch water.

Kaempferol-3-O-glactoside concentration was determined on the basis of kaempferol-3-O-glucoside equivalents.

Dihydrokaempferol concentration was determined on the basis of eriodictyol equivalents.

Extraction methods

LN2 or HW blanching facilitated removal of almond skins prior to aqueous methanol extraction by steeping or ASE. We hypothesized that LN2 blanching would limit heat-induced degradation of almond skin polyphenols induced by HW blanching. Removal of skins by LN2 also reduces the number of samples required for analysis, as it avoids the necessity of testing the blanch water to obtain the concentration of polyphenols extracted into the HW.

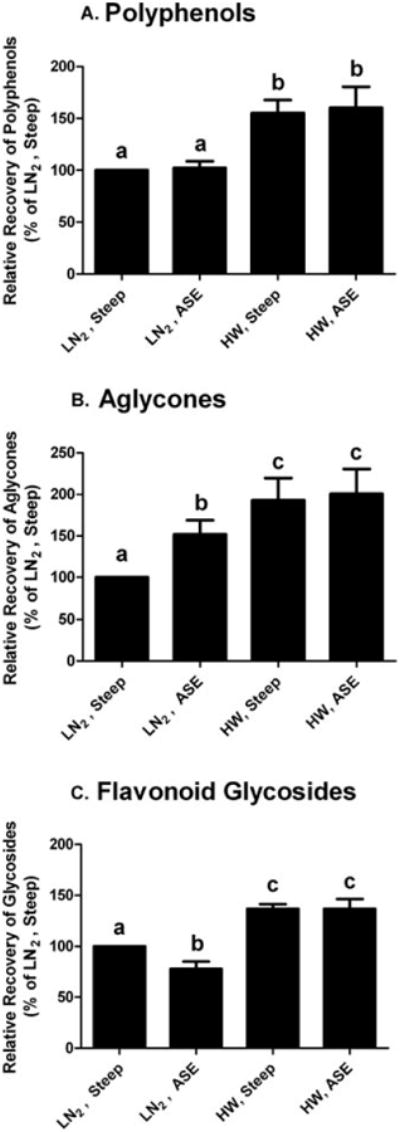

Polyphenol concentration was the greatest in the HW blanched almond extracts, with a mean value of 2.1 mg polyphenols/g skin (Figure 2). On average, HW blanching extracted 74% of the polyphenol content, and steeping or ASE accounted for the remainder (Table 4). Flavonoid glycosides are more polar than the corresponding aglycones, a characteristic consistent with HW blanching extracting 9% more glycosides than aglycones. In contrast to our hypothesis that LN2 blanching would diminish the degradation of polyphenols associated with HW treatment, LN2 blanched almond skin extract had 67% lower polyphenol recovery after both ASE and steeping extraction, than corresponding HW blanching. The additional extraction step of blanching skins in HW likely accounts for the increased recovery rate. Further, it is possible that LN2 blanching may induce a physical change to the almond skin fiber, making polyphenols less extractable.

Figure 2.

Relative recovery of polyphenols (A), aglycones (B), and flavonoid glycosides (C) from almond skin extraction methods. Groups of analysis were as defined as the numbered constituents from Table 1, polyphenols: 1 to 18; aglycones: compounds 3, 4, 10, 14 to 18; glycosides: 1, 2, 5 to 9, 11 to 13. Data are mean ± SD of 3 almond samples. HW = hot water blanching; LN2 = liquid nitrogen blanching; ASE = assisted solvent extraction; steep = extraction by steeping. Bars bearing different letters are significantly different by Tukey's HSD (P ≤ 0.05).

Table 4. Recovery of polyphenol standards and RSD from steeping extraction method using spiked samples (n = 3)*.

| Peak, polyphenols | No matrix | Cellulose | Almond skin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| % recovery | RSD | % recovery | RSD | % recovery | RSD | ||

| (1) | (+)-catechin | 97 | 14 | 98 | 4 | 86 | 5 |

| (2) | (−)-epicatechin | 104 | 15 | 105 | 5 | 107 | 7 |

| (3) | procatechic acid | 89 | 11 | 89 | 4 | 84 | 3 |

| (4) | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | 97 | 35 | 95 | 10 | 83 | 2 |

| (5) | quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | 104 | 12 | 98 | 10 | 116 | 2 |

| (6) | naringenin-7-O-glucoside | 97 | 12 | 95 | 6 | 102 | 4 |

| (7) | quercetin-3-O-galactoside | 83 | 13 | 76 | 7 | 98 | 5 |

| (9) | kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside | 119 | 12 | 117 | 6 | 117 | 1 |

| (11) | kaempferol-3-O-glucoside | 132 | 13 | 129 | 5 | 130 | 0 |

| (14) | eriodictyol | 95 | 14 | 96 | 4 | 106 | 2 |

| (16) | quercetin | 9a | 44 | 23a | 27 | 72b | 1 |

| (17) | kaempferol | 83 | 20 | 72 | 6 | 96 | 1 |

| (18) | isorhamnetin | 28a | 43 | 37a | 11 | 89b | 6 |

| Mean recovery % | 87 | 15 | 87 | 6 | 99 | 5 | |

| aglyconesa | 92 | 14 | 102 | 5 | 92 | 2 | |

| aglyconesa | 110 | 12 | 97 | 6 | 114 | 1 | |

| polyphenolsa | 97 | 14 | 100 | 5 | 97 | 1 | |

Values bearing different letters within rows are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Peaks 1 to 4, 14, 16 to 18.

Peaks 5 to 9, 11.

Peaks 1 to 9, 11, 14, 16 to 18.

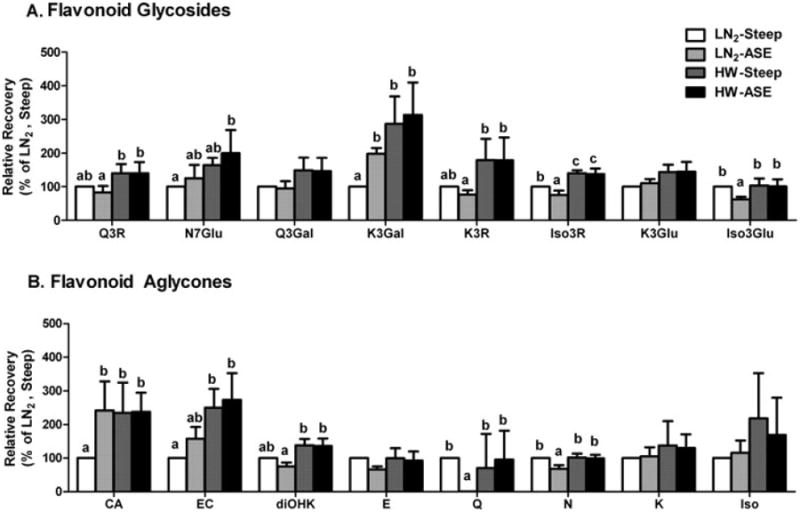

The ASE method extracts phytochemicals with greater efficiency than conventional methods because it can operate at higher temperatures and pressures, and can employ a wider range of solvent polarity during extraction (Peres and others 2006). Thus, we hypothesized ASE would recover more almond polyphenols than methanol steeping. Contrary to our expectations, ASE and steeping extracted equivalent quantities of polyphenols from HW and LN2 blanched almond skins (Figure 2). The flavonoid profiles of HW-ASE and HW-steeping almond skin extracts were similar (Figure 3). Since 75% of the polyphenols were extracted by HW blanching prior to ASE or steeping extraction, the contributions of extraction methods to the profile of polyphenols were minor.

Figure 3.

Relative recovery rates of flavonoid glycosides (A) and flavonoid aglycones (B) from almond skin extraction methods. Data are mean ± SD of 3 almond samples. Abbreviations are as Figure 2 and Q3R = quercetin-3-O-rutinoside; N7Glu = naringenin-7-O-glucoside; Q-3Gal = quercetin-3-O-galactoside; K3Gal = kaempferol-3-O-galactoside; K3R = kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside; Iso3R = isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside; K3Glu = kaempferol-3-O-glucoside; Iso3Glu = isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside; CA = (+)-catechin; EC = (−)-epicatechin; diOHK = dihydrokaempferol; E = eriodictyol; Q = quercetin; N = naringenin; K = kaempferol; Iso = isorhamnetin. Bars bearing different letters are significantly different by Tukey's HSD (P ≤ 0.05).

Although HW extracts had similar polyphenol profiles, ASE and steeping LN2 blanched almond skin extracts were different. The LN2-ASE almond skin extracts had 52% more aglycones but 23% less flavonoid glycosides than the LN2-steeping extracts (Figure 2). The greater yield of aglycones in LN2-ASE extract was primarily due to increased (−)-epicatechin (140%) and (+)-catechin (60%) (Figure 3). The less abundant flavonols, dihydrokaempferol, quercetin, and naringen, were decreased to 76%, 1%, and 68% of LN2-steeping extracts, respectively. The most abundant glycoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside, also decreased 25% in LN2-ASE extracts. Similarly, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, and isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside were also 17% to 38% of the LN2-steeping extracts. Not all flavonol glucosides in LN2-ASE extracts had reduced yields relative to LN2-steeping, as quercetin-3-O-galactoside increased 98% and naringenin-7-O-glucoside increased 25%. Overall, ASE extraction of LN2 blanched almonds may have catalyzed degradation or reduced the extraction efficiency of the majority of flavonoid glycosides.

Method accuracy

Previous descriptions of almond skin polyphenol quantification have not reported the recovery of polyphenols from extraction methods. The steeping extraction method used less solvent and was more cost effective for routine analysis than ASE. Since concentration of polyphenols extracted from almond skin was similar between these methods, we further examined the recovery of polyphenols spiked into samples extracted by steeping. In the present study, 97% of polyphenols (mass basis) were recovered spiking almond skins with standards during the steeping extraction process (Table 4). This indicates the majority of polyphenols by weight were stable during steeping extraction. However, recovery rates of the flavonols quercetin and isorhamnetin were at least 2-fold greater when they were spiked into almond skins rather than cellulose or solvent (P ≤ 0.05). The antioxidant activity of the almond skin extract (Chen and Blumberg 2008) might have prevented the degradation of flavonol standards. Since quercetin rapidly degrades in aqueous solution, additional antioxidants such as ascorbic acid or butylated hydroxytoluene should be added to flavonoid extracts and standards, particularly when they are stored for a long period, even under refrigeration temperatures.

Reports of the quantity of polyphenols extracted from almond skins vary greatly. The present LC-MS method measured 1.4 to 2.2 mg polyphenols/g almond skin. Using comparable extraction methods, Milbury and others (2006) recovered 3.2 to 6 mg polyphenols/g almond skin. The higher values may be an overestimation of flavonoid glycosides by the ECD method resulting from co-elution of oxidizable constituents or because of different almond sources. Monagas and others (2007) reported 0.5 to 0.8 mg polyphenols/g from roasted almond skin and 0.2 to 0.4 mg polyphenols/g from blanched almond skins, which did not include blanch water. Hughey and others (2008) recovered 9.4 and 6.4 mg flavonoids/g of Carmel and Nonpareil almond skins, but employed a more vigorous extraction method by sonicating in aqueous methanol at 4 to 6 °C, which may have led to greater recoveries of flavonoids. The present LC-MS method measured at least 9-fold more kaempferol, isorhamnetin-glucoside, and isorhamnetin-rutinoside in almond skin isolates than reported by Frison-Norrie and Sporns (2002) after extraction with 70% aqueous methanol. Furthermore, flavan-3-ol dimers and oligomers, along with high molecular-weight almond skin polyphenols were not quantified by the current method (Garrido and others 2008; Prodanov and others 2008). The current and previously published methods are in agreement that the major flavonoids in almond skins are isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside, kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, catechin, and epicatechin.

Conclusions

The LC-MS method described here provides a reliable means for quantifying almond skin polyphenols. Comparing our results with those of others indicates that care should be taken to choose extraction conditions and skin removal methods appropriate to the desired application of the results. More research is required to ascertain the relationship of the quantity and profile of polyphenols measured in almond skins by this and other methods to those polyphenols that are bioavailable and bioactive during digestion and metabolism.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by U.S. Dept. of Agriculture (USDA)/Agricultural Research Service under Cooperative Agreement nr 58-1950-7-707 and a grant from the Almond Board of California. Dr. Bolling was supported from NIH IRACDA training grant nr K12 GM074869. The authors are grateful to Guisy Mandalari for consultation on methodology and for the technical assistance of Jennifer O'Leary, Desire Kelley, and Sisca Bolling.

Supported by the Almond Board of California and U.S. Dept. of Agriculture (USDA)/Agricultural Research Service under Cooperative Agreement nr 58-1950-7-707. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the USDA nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

References

- Barreira JC, Ferreira IC, Oliveira MB, Pereira JA. Antioxidant activity and bioactive compounds of ten Portuguese regional and commercial almond cultivars. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:2230–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Blumberg JB. In vitro activity of almond skin polyphenols for scavenging free radicals and inducing quinone reductase. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:4427–34. doi: 10.1021/jf800061z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Milbury PE, Lapsley K, Blumberg JB. Flavonoids from almond skins are bioavailable and act synergistically with vitamins C and E to enhance hamster and human LDL resistance to oxidation. J Nutr. 2005;135:1366–73. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.6.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MJ, Howard LR, Prior RL, Morelock T. Flavonoid content and antioxidant capacity of spinach genotypes determined by high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. J Sci Food Agric. 2008;88:1099–106. [Google Scholar]

- Frison-Norrie S, Sporns P. Identification and quantification of flavonol glycosides in almond seedcoats using maldi-tof MS. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:2782–7. doi: 10.1021/jf0115894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido I, Monagas M, Gomez-Cordoves C, Bartolome B. Polyphenols and antioxidant properties of almond skins: influence of industrial processing. J Food Sci. 2008;73:C106–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughey CA, Wilcox B, Minardi CS, Takehara CW, Sundararaman M, Were LM. Capillary liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry for the rapid identification and quantification of almond flavonoids. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1192:259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Marchie A, Josse AR, Nguyen TH, Faulkner DA, Lapsley KG, Singer W. Effect of almonds on insulin secretion and insulin resistance in nondiabetic hyperlipidemic subjects: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Metabolism. 2008;57:882–7. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JC, Blumberg JB, Ingwersen L, Jenab M, Tucker KL. Tree nuts and peanuts as components of a healthy diet. J Nutr. 2008;138:1736S–40S. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.9.1736S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Jia X, Chen CY, Blumberg JB, Song Y, Zhang W, Zhang X, Ma G, Chen J. Almond consumption reduces oxidative DNA damage and lipid peroxidation in male smokers. J Nutr. 2007;137:2717–22. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.12.2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GL, Winefordner JD. Limit of detection. A closer look at the IUPAC definition. Anal Chem. 1983;55:713A–24A. [Google Scholar]

- Milbury PE, Chen CY, Dolnikowski GG, Blumberg JB. Determination of flavonoids and phenolics and their distribution in almonds. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:5027–33. doi: 10.1021/jf0603937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monagas M, Garrido I, Lebron-Aguilar R, Bartolome B, Gomez-Cordoves C. Almond (prunus dulcis (mill.) d.A. Webb) skins as a potential source of bioactive polyphenols. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:8498–507. doi: 10.1021/jf071780z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peres VF, Saffi J, Melecchi MI, Abad FC, de Assis Jacques R, Martinez MM, Oliveira EC, Caramao EB. Comparison of soxhlet, ultrasound-assisted and pressurized liquid extraction of terpenes, fatty acids and vitamin E from piper gaudichaudianum kunth. J Chromatogr A. 2006;1105:115–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.07.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodanov M, Garrido I, Vacas V, Lebron-Aguilar R, Duenas M, Gomez-Cordoves C, Bartolome B. Ultrafiltration as alternative purification procedure for the characterization of low and high molecular-mass phenolics from almond skins. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2008;609:241–51. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2007.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeram NP, Lee R, Scheuller HS, Heber D. Identification of phenolic compounds in strawberries by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2006;97:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Wang L, Bao Y, Li C. A sensitive method for the detection and quantification of ginkgo flavonols from plasma. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:971–81. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]