Abstract

Inherited ataxias are heterogeneous disorders affecting both children and adults, with over 40 different causative genes, making molecular genetic diagnosis challenging. Although recent advances in next-generation sequencing have significantly improved mutation detection, few treatments exist for patients with inherited ataxia. In two patients with adult-onset cerebellar ataxia and coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) deficiency in muscle, whole exome sequencing revealed mutations in ANO10, which encodes anoctamin 10, a member of a family of putative calcium-activated chloride channels, and the causative gene for autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia-10 (SCAR10). Both patients presented with slowly progressive ataxia and dysarthria leading to severe disability in the sixth decade. Epilepsy and learning difficulties were also present in one patient, while retinal degeneration and cataract were present in the other. The detection of mutations in ANO10 in our patients indicate that ANO10 defects cause secondary low CoQ10 and SCAR10 patients may benefit from CoQ10 supplementation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00415-014-7476-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Autosomal recessive ataxia, Mitochondrial, Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) deficiency, ANO10

Introduction

Despite major advances in understanding the genetic forms of ataxia, approximately half of the patients with recessive ataxia—in particular, adults—do not receive a molecular diagnosis [1]. Given the numerous etiologies, genetic diagnosis requires the performance of a wide range of analyses and consensus on the diagnostic value of these examinations is lacking. Recent advances in next-generation sequencing have significantly improved the mutation detection rate of inherited ataxias, but treatments for inherited ataxia remain inadequate. Clinical characterization and evaluation for subtle additional features can provide clues to the precise diagnosis [2].

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) deficiencies comprise a heterogeneous group of autosomal recessive conditions with primary deficiencies caused by mutations in genes encoding CoQ10 biosynthesis enzymes and secondary forms caused by genetic defects not directly related to CoQ10 biosynthesis [3].Ataxia is the most common clinical phenotype associated with CoQ10 deficiency [3]. The first causative mutations identified in the ataxic form of CoQ10 deficiency were detected in APTX, which encodes aprataxin and is the causative gene for ataxia with oculomotor apraxia 1 (AOA1) [4]. Reduced CoQ10 levels were reported in some but not all AOA1 patients with confirmed pathogenic APTX mutations [4]. Autosomal recessive mutations in ADCK3, which encodes a kinase involved in CoQ10 biosynthesis, have been identified in several families with juvenile- or adult-onset ataxia, confirming the link between ataxia and CoQ10 deficiencies [3, 5]. Some patients improved on CoQ10 supplementation [3, 5]; the lack of improvement in some patients has been attributed to the reduced bioavailability of CoQ10 and its limited ability to cross the blood brain barrier; however, worsening has been reported for one patient treated with Idebenone, a short-chain CoQ analog [6].

In our genetic characterization of a group of patients with unexplained recessive or sporadic cerebellar ataxia and low muscle CoQ10, we identified pathogenic mutations in ANO10 in two families.

Case series

This study had institutional and ethical review board approval and all the patients gave informed consent.

Patients and methods

We studied 40 unrelated patients with unexplained ataxia and low CoQ10 in skeletal muscle biopsies without a dominant family history, in whom well-known genetic causes of spinocerebellar ataxias (SCA1,2,3,6,7,17, DRPLA and Friedreich ataxia) and other possible causes of a progressive ataxia were excluded by clinical and laboratory investigations (brain MRI, CSF analyses, normal routine biochemistry, blood cell counts, metabolic screening for acyl-carnitine profiles, urine organic acids, very long chain fatty acids, phytanic acid, vitamins E, A, B12, alpha-fetoprotein, serum protein electrophoresis, lipoproteins, lysosomal enzymes, copper, ceruloplasmin, ferritin, iron, and paraneoplastic antibodies).

CoQ10 measurement in plasma, fibroblasts and skeletal muscle was performed as described [7].

Molecular genetics

Genetic analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) for deletions, depletion, and point mutations in muscle DNA as well as direct sequencing of POLG, PDSS1, PDSS2, COQ2, COQ9, CABC1/ADCK3 and APTX in blood DNA were normal in all patients [3]. In patient 1, whole exome sequencing was performed in genomic DNA, isolated from lymphocytes (DNeasy®, Qiagen, Valencia, CA), fragmented and enriched by Illumina TruSeq™ 62 Mb exome capture, and sequenced (Illumina HiSeq 2000, 100 bp paired-end reads). The in-house bioinformatics pipeline included alignment to the human reference genome (UCSC hg19), reformatting, and variant detection (Varscan v2.2, Dindel v1.01), as described previously [8]. On-target variant filtering excluded those with minor allele frequency greater >0.01 in several databases. Rare homozygous and compound heterozygous variants were defined, and protein altering and/or putative ‘disease causing’ mutations, along with their functional annotation, were identified using ANNOVAR [8]. Putative pathogenic variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing, using custom-designed primers (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu) on an ABI 3130XL (Life Technologies, CA, USA), allowing segregation analyses (Fig. 1a). The primers used for genomic DNA (NG_028216.1) and cDNA (NM_018075.3) analysis of ANO10 are listed in the Supplementary Materials (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

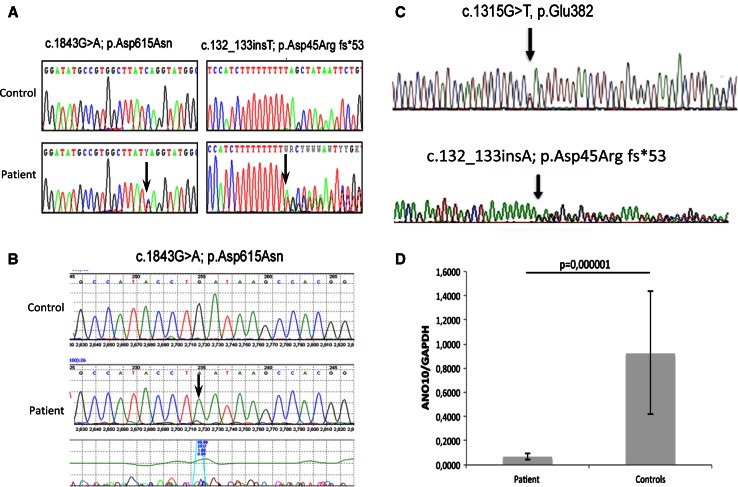

Fig. 1.

Detection of heterozygous ANO10 variants in genomic DNA of patient 1 (a). cDNA analysis of patient 1 detected the c.1843G>A, p.Asp615Asn mutation in hemizygous form, confirming compound heterozygosity (b), Compound heterozygous mutations were detected in patient 2 (c), Q-RT-PCR showed significantly decreased ANO10 mRNA levels in patient 2’s fibroblast, compared with controls (d). Values are expressed as mean ± SD of patient and controls (N = 3)

To measure ANO10 mRNA expression level, skin fibroblasts from the patients were grown and total RNA was extracted using the Pure Link™ RNA Mini Kit (Ambion, Life Technologies). RNA concentration was measured using a Nanodrop. Subsequently, 100 ng of RNA was converted into cDNA using SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using TaqMan Assays for ANO10 and GAPDH (Applied Biosystems).

Results

Patient 1 is a 57-year-old English woman who is the second child of healthy, non-consanguineous parents and has a healthy brother. After normal early development she developed generalized epilepsy and learning difficulties at 7 years of age. Her epilepsy was well-controlled, but at age 45 years, she developed gait disturbance, ataxia and slurred speech. She became wheelchair-bound from age 50 years. On examination she had slow saccades but no nystagmus, dysarthria, bilateral dysmetria and a severe trunk ataxia. Although she had no weakness and deep tendon reflexes were normal, she was permanently wheelchair-bound and could not stand or walk due to severe trunk ataxia and had some cognitive dysfunction. Brain MRI revealed marked parieto-occipital and cerebellar atrophy. Nerve conduction studies and electromyography were normal. Skeletal muscle biopsy was performed at age 53 years and showed normal histology, but an isolated complex III deficiency (158 normalize to citrate synthase, normal mean ± standard deviation 554 ± 345) and low CoQ10 (104 pmol/mg protein, normal range 140–580). CoQ10 in fibroblasts was normal (147 pmol/mg protein, normal range 75–190 pmol/mg protein).

Supplementation with 1,000 mg/day CoQ10 had beneficial effects on the patient’s fatigue and mobility within 3–4 months. She was able to stand up and do a few steps and her cognition has slightly improved. She had no seizures and no epileptic activity on her follow-up EEG, therefore, antiepileptic medication was slowly withdrawn.

Genetic analysis

Whole exome sequencing detected potentially disease causing variants in nine genes, but only the variants in ANO10 segregated with the disease and alter a known disease gene. Two potentially disease causing variants (c.132_133insT; p.Asp45Arg fs*53 and c.1843G>A; p.Asp615Asn) were detected in ANO10 (Fig. 1a), which were not present in her healthy brother. Unfortunately, both parents of patient 1 had died and she did not have any children. One of the detected mutations was a frame-shift mutation leading to a premature stop codon. The other mutation c.1843G>A; p.Asp615Asn is a missense change of a conserved amino acid that has been detected extremely rarely (rs138000380—1,000 genomes shows only 1 heterozygous) and both mutation taster (0.999) and PolyPhen (0.559) predicted that it is disease causing. cDNA analysis for ANO10 detected only one allele, which was supported by the hemizygous state of the c.1843G>A; p.Asp615Asn change (Fig. 1b).

The detection of pathogenic ANO10 mutations in our patient with the ataxic form of CoQ10 deficiency prompted us to perform sequencing of ANO10 in 36 further patients with low CoQ10 in muscle, fibroblasts, or CSF [3], and we detected pathogenic mutations in one additional patient.

Patient 2 is a 52-year-old woman with neurologically normal non-consanguineous parents, and two healthy siblings. At the age of 30 years, she presented with walking difficulties, slurred speech, and oscilloscopia. The walking instability progressed slowly and she developed retinal detachments that were treated with multiple surgeries. At age 50, because of frequent falls, she started to use a walker to ambulate long distance. Other ocular problems include: retinal fibrosis, cataracts, vitreous fluid opacity and possible macular degeneration. Neurological examination revealed a stiff-legged wide-based gait with scissoring, slight eyelid ptosis, primary gaze down-beat nystagmus, and brisk tendon reflexes with ankle clonus, crossed hip adductors, and bilateral Hoffmann signs but Babinski signs were absent. Dysmetria and intention tremor on finger-nose-finger and heel-to-shin test were present. Brain MRI revealed marked cerebellar atrophy involving both lobes and the vermis. Muscle biopsy showed fiber type 2 atrophy. Respiratory chain complex activities measured in muscle tissue were normal.

CoQ10 level in the fibroblasts of the patient (50.6 ± 7.3 nmol/μg protein) was normal (concurrent controls 48.3 ± 27.8 nmol/μg protein); however, levels of CoQ10 were decreased in plasma (0.41 μg/ml, normal range 0.8 ± 0.35 μg/ml) and CSF (410 μg/l, normal range 450–1420 μg/l); and borderline in muscle (21.2 μg/g, normal range 32 ± 6 μg/g).

CoQ10 supplementation (120–180 mg/day) led to an initial mild improvement of the ataxia and gait. Evaluation by the international co-operative ataxia rating scale (ICAR), showed an improvement in the oculomotor movement score (from 4/6 to 3/6) and in the dysarthria score (from 6/8 to 5/8).

Genetic analysis

Direct sequencing of ANO10 in genomic DNA from patient 2 revealed two heterozygous variants, c.132_133insT; p.Asp45Argfs*53 in exon 2, also present in patient 1, and c.1315G>T, p.Glu382*, in exon 6 (Fig. 1d). Both variants generate premature stop codons with truncated protein of 53 aa and 382 aa, respectively (wild-type protein: 660 aa).

The 2 mutations segregated with the disease in the family (the mother was heterozygous for the c.132_133insT; p.Asp45Argfs*53 variant, both healthy siblings were homozygous wild type; and the father’s DNA was not available) and were not detected in 124 ethnically-matched control alleles. cDNA analysis showed a significant reduction of ANO10 expression level in cultured skin fibroblast from patient 2 compared to controls (Fig. 1d).

Measurement of CoQ10 in fibroblasts of a previously published patient (family B, II:5) [9] in carrying pathogenic ANO10 mutations was normal result (156 pmol/mg protein, normal range 75–190 pmol/mg protein), however, muscle was not available for CoQ10 analysis.

Discussion

Anoctamin 10 (ANO10), also known as TMEM16 K, is a member of the human anoctamin (ANO) family of proteins, which consists of at least nine other proteins, all containing eight transmembrane domains and a DUF590 domain [9, 10]. It has been suggested that the anoctamin genes encode cell- and tissue-specific calcium-activated chloride channels, however, experimental data are limited [10]. The clinical presentations of mutations in the various anoctamin genes are very heterogeneous, and include limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (ANO5), skeletal abnormalities (Gnathodiaphyseal dysplasia due to ANO5 mutations), blood cell disorders (Scott syndrome caused by ANO6 defects), as well as progressive neurological presentations of autosomal dominant dystonia (DYT24 due to ANO3 mutations) and cerebellar ataxia and atrophy (ANO10 defects) [10].

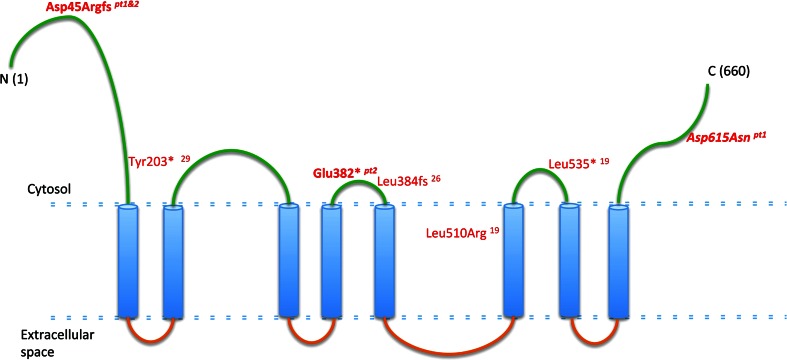

Mutations in ANO10 (Fig. 2) has been associated with autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia in only five families [9, 11, 12]. The clinical presentation of the previously reported patients showed cerebellar ataxia and atrophy with variable age-at-onset between 13 and 45 years, brisk reflexes, and eye movement abnormalities. Additional features included: intellectual deficit, motor neuron involvement and epilepsy in some but not all patients, illustrating the significant clinical variability (Table 1). Although the clinical presentation of our patients resembles the previously reported cases, and confirms the clinical phenotype of ANO10 deficiency, muscle biopsies and measurement of CoQ10 have never been assessed before in this condition. Because 2 out of 40 patients (5 %) from our cohort carried mutations in ANO10, we suggest that defects in this gene should be considered in patients with unexplained ataxia and low CoQ10 in skeletal muscle.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of ANO10. In green: putative intra-cytoplasmic region, in blue: putative transmembrane domains, in orange: putative extracellular domains. Text in red: previously reported mutations; in bold italic: mutations found in our patients

Table 1.

Clinical summary of patients 1 and 2 reported in this study and the previously reported patients carrying pathogenic ANO10 mutations

| Ref | Age of onset (years) | Country of origin | Genotype | Gait ataxia | Dysarthria | Limb ataxia | Cortico-spinal tract | MRI | Opthalmologic features | EMG | Mental retardation | Other features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 25 | Netherlands | c.1529T>G; p.Leu510Arg | ++ | ++ | ++ | ↑DTR EPR | CA | Downbeat nys | II MU involvement | – | Cold and blue toes |

| 6 | 20 | Netherlands | c.1529T>G; p.Leu510Arg | ++ | ++ | ++ | ↑DTR | CA | Downbeat nys | II MU involvement | – | Wasting and fasciculations proximal leg muscles |

| 6 | 32 | Netherlands | c.1529T>G; p.Leu510Arg | + | + | + | ↑DTR | CA | Downbeat nys | NP | – | Cold and blue toes |

| 6 | 15 | Serbia | c.1150_1151del; p.Leu384 fs | ++ | ++ | + | ↑DTR | CA | Hor and ver nys | NP | + | Inspiratory stridor |

| 6 | 15 | Serbia | c.1150_1151del; p.Leu384 fs | ++ | + | + | ↑DTR | CA | Hor and ver nys | NP | + | Pes cavus |

| 6 | 13 | Serbia | c.1150_1151del; p.Leu384 fs | ++ | ++ | + | ↑DTR | CA | Hor nys | II MU involvement | – | Fasciculations proximal leg muscles, inspiratory stridor, vocal cord paresis |

| 6 | 45 | France |

c.1476 + 1G>T c.1640del; p.Leu535* |

+++ | ++ | ++ | ↑DTR | NP | Saccadic pursuit, nys | NP | – | Rest tremor, pes cavus |

| 6 | 25 | France |

c.1476 + 1G>T c.1640del; p.Leu535* |

++ | ++ | ++ | ↑DTR | CA | Multi-dir nys | Normal | – | Episodic diplopia, pes cavus |

| 8 | 16 | Bulgaria | c.1150_1151del; p.Leu384 fs | +++ | ++ | + | ↑DTR | NP | Hor and ver nys | NP | – | NR |

| 8 | 17 | Bulgaria | c.1150_1151del; p.Leu384 fs | ++ | ++ | + | ↑DTR EPR | CA | Downbeat nys | II MU involvement | + | NR |

| 8 | 17 | Bulgaria | c.1150_1151del; p.Leu384 fs | ++ | ++ | + | ↑DTR | NP | Downbeat nys | Normal | + | NR |

| 9 | 46 | Japan | c.609C>G; p.Tyr203* | ++ | ++ | NA | ↑DTR | Mild CA | Saccadic pursuit | Normal | – | Seizures, constipation |

| P1 (this paper) | 7 | United Kingdom |

c.132_133insT; p.Asp45Argfs c.1843G>A; p.Asp615Asn |

+++ | ++ | ++ | Normal | Parieto-occipital, CA | Saccadic pursuit | Normal | + | Seizures, Low CoQ10 in muscle |

| P2 (this paper) | 30 | United States |

c.132_133insT; p.Asp45Argfs c.1315G>T; p.Glu382* |

++ | ++ | ++ | ↑DTR Hoffman sign | Marked CA | Downbeat nys | Normal | – | Retinal degen, cataract, low CoQ10 in blood and CSF |

Ref reference, Age of onset (years), MRI magnetic resonance imaging, + Mild, ++ Moderate,+++ Severe, ↑ increased, DTR deep tendon reflexes, EPR extension plantar reflex, NP not preformed, hor horizontal, ver vertical, nys nystagmus, Multi-dir multi-directional, MU motor unit, NA not available, CoQ10 coenzyme Q10, CSF cerebral spinal fluid

The low CoQ10 levels and the beneficial effect of CoQ10 supplementation in our patients carrying ANO10 mutations are unexpected findings and raise the question whether low CoQ10 contributes to the disease pathomechanism, potentially by affecting CoQ10 dependent functions, which was supported by slightly low CoQ10 in fibroblasts of a previously reported patient [9]. Interestingly, in one of our patients, seizures disappeared after CoQ10 supplementation, as previously reported in a patient with CoQ10 deficiency and cerebellar ataxia due to APTX mutations [4]. It has been postulated that cerebellar ataxia in patients with ANO10 deficiency may be due to abnormal calcium signaling in Purkinje cells [10]. Calcium signaling has been shown to be important for mitochondria, and this year, mutations in the gene encoding for the mitochondrial calcium uptake 1 (MICU1) protein have been identified in some families with proximal myopathy, learning difficulties and a progressive extrapyramidal movement disorder [13]. The role of ANO10 and CoQ10 in calcium signaling need to be further investigated. Functional studies in additional patients or animal models will be helpful to characterize the pathomechanism of ANO10 mutations and will define the role of CoQ10 deficiency in ANO10-related disease. The observations of low CoQ10 levels and the beneficial effect of high-dose CoQ10 supplementation in our patients suggest that CoQ10 should be considered in the therapy of ANO10 deficiency.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

RH was supported by the Medical Research Council (UK) (G1000848) and the European Research Council (309548). PFC is a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow in Clinical Science and an NIHR Senior Investigator who also receives funding from the Medical Research Council (UK), the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society, and the UK NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Ageing and Age-related disease award to the Newcastle upon Tyne Foundation Hospitals NHS Trust. RWT receives support from the Wellcome Trust Centre for Mitochondrial Research (096919Z/11/Z) and the UK NHS Highly Specialized “Rare Mitochondrial Disorders of Adults and Children” Service. MA is funded by an NIHR CSO Healthcare Scientist research fellowship. VMR was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Republic of Serbia (Project No. 17 3016; 17 508). HL was supported by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement No. 305444 (RD-Connect) and 305121 (Neuromics). We are grateful for the Medical Research Council (MRC) Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases Biobank Newcastle for providing patient cell lines for this project. CMQ is supported by K23HD065871 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), and from a Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) grant. MH is supported by NIH Grants R01HD057543, R01HD056103 and U54 NS078059, a MDA grant, and by the Marriott Mitochondrial Disorder Clinical Research Fund (MMDCRF).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

A. Balreira and V. Boczonadi joint as first authors. C. M. Quinzii and R. Horvath contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Catarina M. Quinzii, Phone: +12123421296, Email: cmq2101@cumc.columbia.edu

Rita Horvath, Phone: +44 191 2418855, Email: rita.horvath@ncl.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Anheim M, Tranchant C, Koenig M. The autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxias. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(7):636–646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1006610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Németh AH, Kwasniewska AC, Lise S, et al. Next generation sequencing for molecular diagnosis of neurological disorders using ataxias as a model. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 10):3106–3118. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emmanuele V, López LC, Berardo A, et al. Heterogeneity of coenzyme Q10 deficiency: patient study and literature review. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(8):978–983. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinzii CM, Kattah AG, Naini A, et al. Coenzyme Q deficiency and cerebellar ataxia associated with an aprataxin mutation. Neurology. 2005;64(3):539–541. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150588.75281.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mignot C, Apartis E, Durr A, et al. Phenotypic variability in ARCA2 and identification of a core ataxic phenotype with slow progression. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:173. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auré K, Benoist JF, Ogier de Baulny H, et al. Progression despite replacement of a myopathic form of coenzyme Q10 defect. Neurology. 2004;63(4):727–729. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000134607.76780.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.López LC, Schuelke M, Quinzii CM, et al. Leigh syndrome with nephropathy and CoQ10 deficiency due to decaprenyl diphosphate synthase subunit 2 (PDSS2) mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79(6):1125–1129. doi: 10.1086/510023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfeffer G, Elliott HR, Griffin H, et al. Titin mutation segregates with hereditary myopathy with early respiratory failure. Brain. 2012;135(Pt6):1695–1713. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vermeer S, Hoischen A, Meijer RP, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of a 12.5 Mb homozygous region reveals ANO10 mutations in patients with autosomal-recessive cerebellar ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(6):813–819. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duran C, Hartzell HC. Physiological roles and diseases of Tmem16/Anoctamin proteins: are they all chloride channels? Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32(6):685–692. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamova T, Florez L, Guergueltcheva V, et al. ANO10 c.1150_1151del is a founder mutation causing autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia in Roma/Gypsies. J Neurol. 2012;59(5):906–911. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maruyama H, Morino H, Miyamoto R, et al. Exome sequencing reveals a novel ANO10 mutation in a Japanese patient with autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia. Clin Genet. 2014;85(3):296–297. doi: 10.1111/cge.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Logan CV, Szabadkai G, Sharpe JA, et al. UK10 K Consortium. Loss-of-function mutations in MICU1 cause a brain and muscle disorder linked to primary alterations in mitochondrial calcium signaling. Nat Genet. 2014;46(2):188–193. doi: 10.1038/ng.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.