Abstract

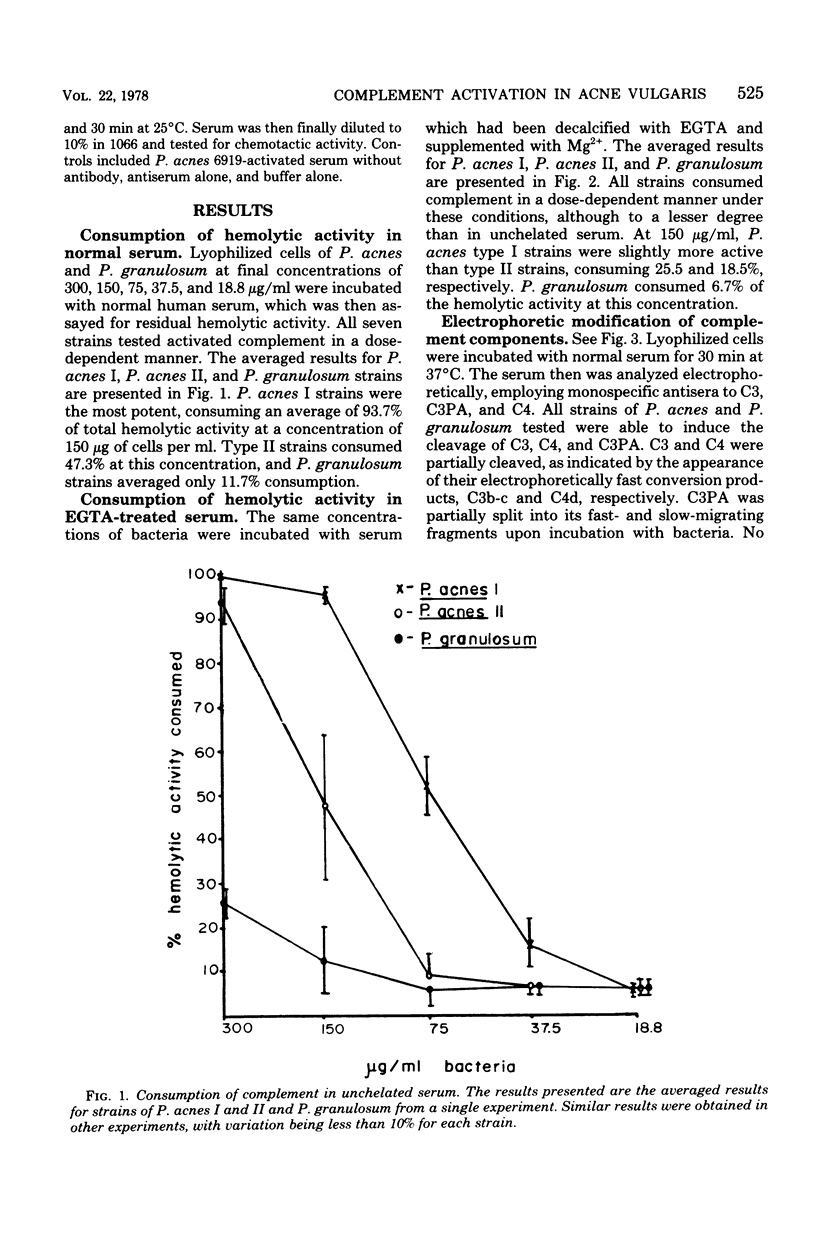

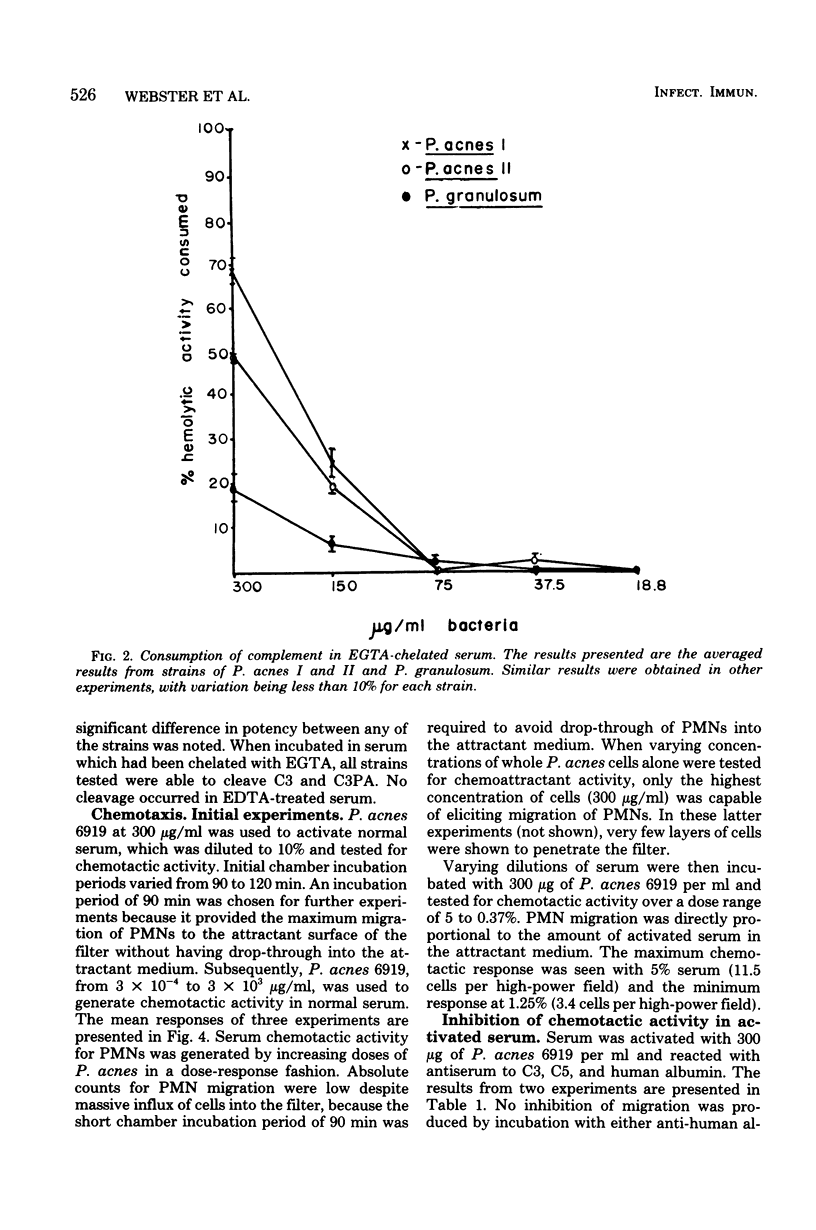

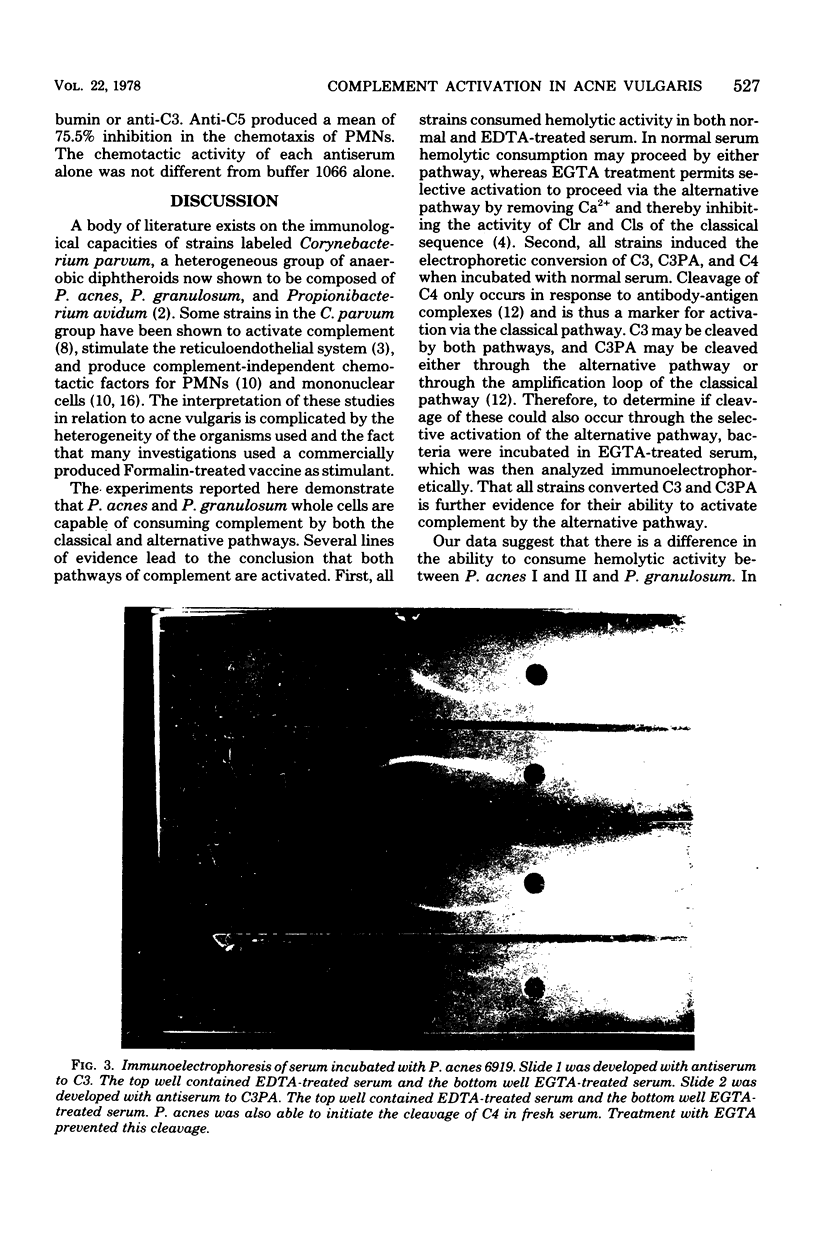

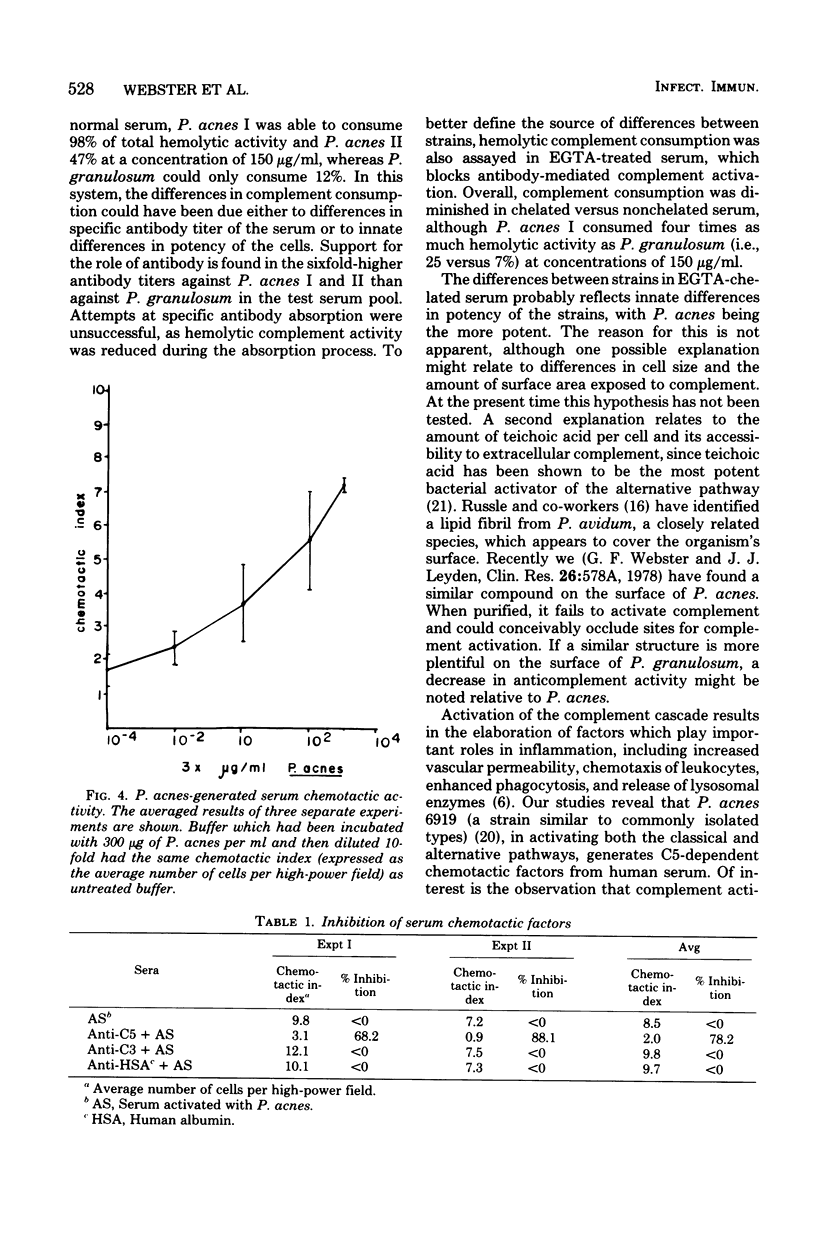

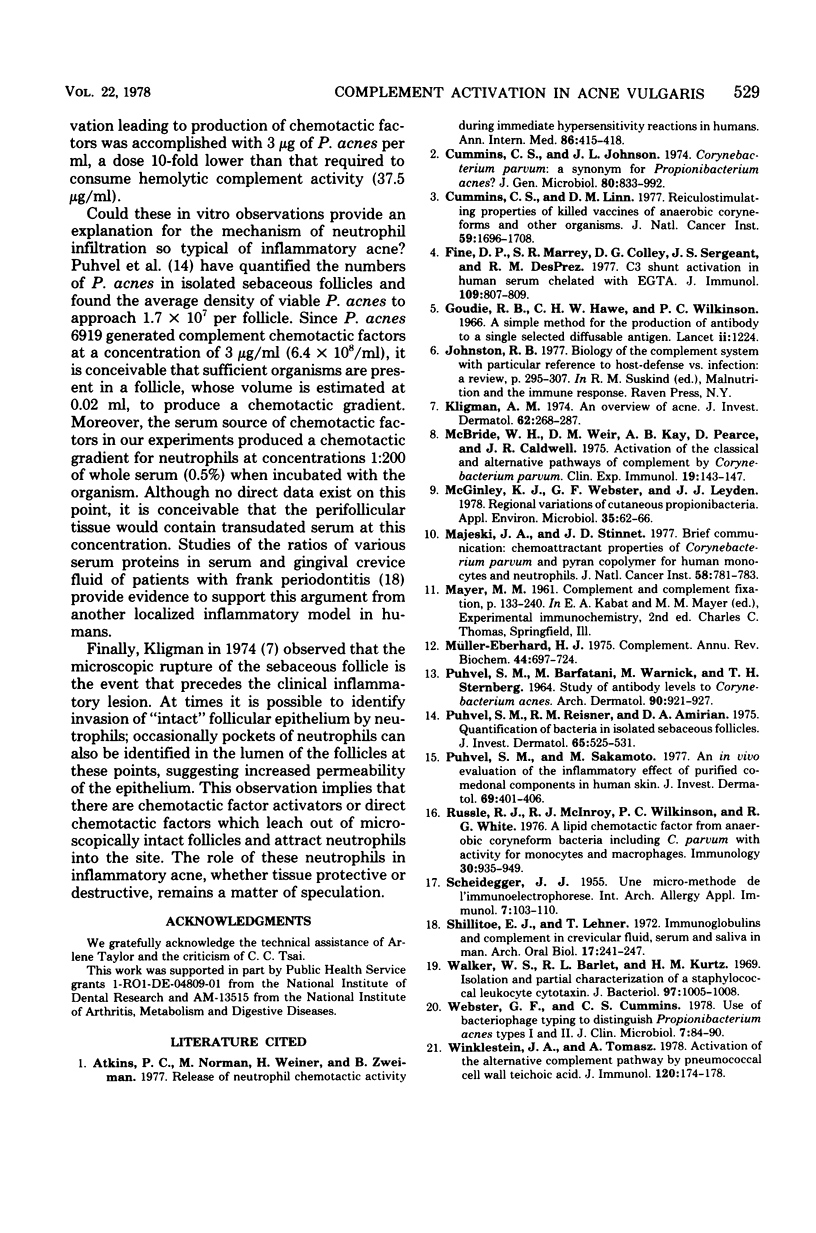

To better define the role of bacteria in inflammatory acne vulgaris, we have investigated the ability of four strains of Propionibacterium acnes and three strains of Propionibacterium granulosum to activate complement. Complement activation was assayed by incubating normal human serum with varying concentrations of each strain and measuring residual total hemolytic complement activity. When serum was tested unaltered, P. acnes strains were approximately threefold more potent than an equal weight of P. granulosum in consuming complement, which could reflect classical and/or alternative pathway activation. All strains also consumed complement in serum chelated with ethyleneglycol-bis (beta-aminoethyl ether)-N,N'-tetraacetic acid, which selectively assays alternative pathway activation. Incubation of unaltered serum with both P. acnes and P. granulosum resulted in immunoelectrophoretic conversion of C4, C3, and factor B of the alternative pathway. Incubation of chelated serum resulted in conversion of C3 and factor B. These data taken together suggest that both species can activate complement through either pathway. Serum incubated with P. acnes was chemotactic for polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and this chemotactic activity was largely C5 dependent as shown by antibody inhibition. It is suggested that complement activation may occur in vivo in acne, and the inflammatory response may be contributed to by the generation of C5-dependent chemotactic factors.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Atkins P. C., Norman M., Weiner H., Zweiman B. Release of neutrophil chemotactic activity during immediate hypersensitivity reactions in humans. Ann Intern Med. 1977 Apr;86(4):415–418. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-4-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins C. S., Linn D. M. Reticulostimulating properties of killed vaccines of anaerobic coryneforms and other organisms. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977 Dec;59(6):1697–1708. doi: 10.1093/jnci/59.6.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine D. P., Marney S. R., Jr, Colley D. G., Sergent J. S., Des Prez R. M. C3 shunt activation in human serum chelated with EGTA. J Immunol. 1972 Oct;109(4):807–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudie R. B., Horne C. H., Wilkinson P. C. A simple method for producing antibody specific to a single selected diffusible antigen. Lancet. 1966 Dec 3;2(7475):1224–1226. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)92305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kligman A. M. An overview of acne. J Invest Dermatol. 1974 Mar;62(3):268–287. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12676801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeski J. A., Stinnett J. D. Chemoattractant properties of Corynebacterium parvum and pyran copolymer for human monocytes and neutrophils. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977 Mar;58(3):781–783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/58.3.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride W. H., Weir D. M., Kay A. B., Pearce D., Caldwell J. R. Activation of the classical and alternate pathways of complement by Corynebacterium parvum. Clin Exp Immunol. 1975 Jan;19(1):143–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley K. J., Webster G. F., Leyden J. J. Regional variations of cutaneous propionibacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978 Jan;35(1):62–66. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.1.62-66.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Eberhard H. J. Complement. Annu Rev Biochem. 1975;44:697–724. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.44.070175.003405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhvel S. M., Reisner R. M., Amirian D. A. Quantification of bacteria in isolated pilosebaceous follicles in normal skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1975 Dec;65(6):525–531. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12610239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhvel S. M., Sakamoto M. An in vivo evaluation of the inflammatory effect of purified comedonal components in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1977 Oct;69(4):401–406. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12510326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R. J., McInroy R. J., Wilkinson P. C., White R. G. A lipid chemotactic factor from anaerobic coryneform bacteria including Corynebacterium parvum with activity for macrophages and monocytes. Immunology. 1976 Jun;30(6):935–949. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHEIDEGGER J. J. Une micro-méthode de l'immuno-electrophorèse. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1955;7(2):103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillitoe E. J., Lehner T. Immunoglobulins and complement in crevicular fluid, serum and saliva in man. Arch Oral Biol. 1972 Feb;17(2):241–247. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(72)90206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker W. S., Barlet R. L., Kurtz H. M. Isolation and partial characterization of a staphylococcal leukocyte cytotaxin. J Bacteriol. 1969 Mar;97(3):1005–1008. doi: 10.1128/jb.97.3.1005-1008.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster G. F., Cummins C. S. Use of bacteriophage typing to distinguish Propionibacterium acne types I and II. J Clin Microbiol. 1978 Jan;7(1):84–90. doi: 10.1128/jcm.7.1.84-90.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelstein J. A., Tomasz A. Activation of the alternative complement pathway by pneumococcal cell wall teichoic acid. J Immunol. 1978 Jan;120(1):174–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]