The prevalence of diabetes mellitus worldwide is increasing, in part due to an obesity epidemic. Thus, prevention and treatment of vision loss from diabetic retinopathy, including proliferative diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema (DME), has become more important.1 Diabetic macular edema, a swelling of the central part of the macula, affects approximately 746,000 adults aged 40 or older in the United States (approximately 4% with diabetes).2

For some patients, progression or worsening of diabetic retinopathy can be prevented or improved through control of diabetes or blood pressure.3 For others, the standard treatment for DME since the mid-1980s has been laser photocoagulation (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study guidelines).4 Laser photocoagulation, applied to microaneurysms and other areas within a thickened macula, can diminish the risk of moderate visual loss by approximately 50% and improve vision in approximately 30% of eyes with vision impairment, although approximately 15% have vision loss despite this treatment.4

About ten years ago, intravitreal injections of corticosteroids were tested as an alternative to laser photocoagulation because it was suspected that diabetic retinopathy involved an inflammatory component. Intravitreal corticosteroids often decrease macular edema and improve vision but at least half of these patients will develop adverse effects, including elevated intraocular pressure, which can lead to glaucoma.5 Furthermore, almost all patients without prior cataract surgery will develop cataracts. Cataract extraction in the presence of DME may result in further vision loss from worsening edema. A clinical trial from the NIH-sponsored Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net) (NCT00444600) involving 691 participants showed an initial benefit of corticosteroids plus prompt laser over laser alone in the first six months after treatment; however, by two years, the effects of corticosteroids plus laser were not superior to laser alone on vision or macular edema.5

About 7 years ago, following recognition that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays a major role in both retinal neovascularization and DME, investigators evaluated the use of intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF medications. The first FDA-approved anti-VEGF medication for intravitreal use, pegaptanib, had limited efficacy. Bevacizumab, which was already approved as an intravenous anti-cancer therapy, was subsequently evaluated via intravitreal injection for the neovascular stage of age-related macular degeneration and for DME. Subsequently an FDA approved VEGF inhibitor; ranibizumab became available. There now is widespread use of 3 anti-VEGF drugs for DME including, aflibercept (not yet FDA approved), bevacizumab (not FDA approved), and ranibizumab (FDA approved).

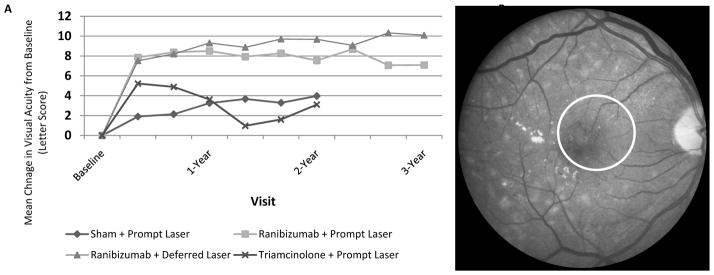

The efficacy of anti-VEGF treatment compared with laser photocoagulation was evaluated in studies by the DRCR.net and by industry. A DRCR.net randomized clinical trial played a role in changing the treatment approach for DME. The trial, involving 691 participants, compared the following: 1) sham intravitreal injection plus laser (control), 2) intravitreal ranibizumab injection with prompt laser, 3) intravitreal ranibizumab injection with deferred laser (beyond 24 weeks only in eyes that were not responding well to ranibizumab alone), and 4) intravitreal triamcinolone with prompt laser photocoagulation. Results demonstrated that ranibizumab was more effective in improving mean visual acuity (Figure 1a), preventing central vision loss, and increasing the percentage of eyes with substantial visual improvement.6 At the 2-year visit, 49% of eyes (n = 139) treated with ranibizumab plus deferred laser showed substantial improvement compared with 36% of eyes (n = 211) in the sham injection plus laser group. Furthermore, 3% of eyes treated with ranibizumab plus deferred laser had substantial loss of vision compared with 13% of eyes in the sham plus laser group.5 Mean vision improvements were maintained over at least 3 years.6 The median numbers of intravitreal injections in the first, second, and third years in the ranibizumab groups were 8 to 9, 3 to 4, and 1 to 2, respectively.6 Serious adverse events were rare; 3 eyes (0.8% [n = 375]) had injection-related endophthalmitis in the ranibizumab groups while no systemic events attributable to study treatment were apparent.5

Figure 1.

Based on Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network results,6 a. mean visual acuity change from baseline among 4 groups randomized to prompt focal/grid laser plus a sham intravitreal injection, prompt laser plus intravitreal ranibizumab, deferred laser (for at least 24 weeks) plus intravitreal ranibizumab, or prompt laser plus intravitreal corticosteroids through 2 years with a three year comparison of the two ranibizumab groups; b. fundus photograph of case with diabetic macular edema and lipid (circle), i.e., hard exudates, near the center of the macula.

The DRCR.net developed a treatment algorithm for ranibizumab in eyes with visual acuity loss from DME that recommends that treatment be continued while DME is improving, discontinued when edema stabilizes, and reinitiated when edema worsens.7 Studies by Genentech using monthly injections of ranibizumab (approved by the FDA for this indication) for at least two years, by Novartis using ranibizumab with an as needed algorithm similar to the DRCR.net, and by Regeneron using aflibercept, showed similar benefits.

Intravitreal anti-VEGF injections have now replaced laser as standard treatment for DME,8 however laser photocoagulation may still be used when a complete response is not seen. Not all eyes that receive anti-VEGF or laser photocoagulation show complete resolution of DME with improvement of vision. Therefore, other treatments are being considered, including combination corticosteroids with anti-VEGF agents, switching anti-VEGF agents, increasing the frequency of injections, utilization of surgical approaches, and others.

Many persons with DME in the United States are not receiving recommended care that can help prevent visual impairment and blindness.9 Therefore, health care professionals managing patients with diabetes should be aware of the importance of retinal examinations to diagnose diabetic retinopathy including DME and proliferative retinopathy. Periodic examinations by a vision specialist (who can accurately assess the severity of diabetic retinopathy as well as whether DME is present) are necessary. Although controlling diabetes and hypertension can have a positive effect on diabetic retinopathy, these actions do not replace ophthalmic examinations, which should occur every 1 to 2 years in persons with diabetes but without diabetic retinopathy. Patients with retinopathy require more frequent examinations by vision specialists skilled in the management of diabetic retinopathy.

What does the future hold for DME? In a randomized multi-center clinical trial (www.clinicaltrials.gov; identifier NCT01627249, registration June 21, 2012), the DRCR.net is studying the relative efficacy of three different anti-VEGF agents including aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab. Results of this trial of 660 study participants should be available in the fall of 2014. Additionally, the DRCR.net has begun a randomized, controlled, clinical trial (www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT01909791, registration July 23, 2013) to determine whether prompt initiation of treatment with anti-VEGF or laser before loss of vision in eyes with central DME gives a more favorable outcome compared with observation until vision loss occurs. The search for agents to prevent the development or worsening of diabetic retinopathy continues, although no agent is nearing approval. Additionally, since the current standard care, especially within the first two years after initiating treatment, requires frequent visits and ocular intravitreal injections, better medication delivery systems are under investigation by many groups. Possibilities include uses of nanotechnology, depot deposits, uveoscleral delivery, transcleral delivery, use of topical or systemic treatments, and others. While recent advances in controlling vision loss in DME are apparent, the near future will likely show rapid progress.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Supported through cooperative agreements from the National Eye Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services EY14231, EY14229, EY18817

Footnotes

Disclaimer: Dr Bressler is the Editor of JAMA Ophthalmology and on The JAMA Network Editorial Board. He was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to accept this article for publication.

Financial Disclosures: The funding organization (National Institutes of Health) did not participate in the preparation of the manuscript. Lee M. Jampol: no disclosures. Neil M. Bressler: Grants to investigators at The Johns Hopkins University are negotiated and administered by the institution (such as the School of Medicine) which receives the grants, typically through the Office of Research Administration. Individual investigators who participate in the sponsored project(s) are not directly compensated by the sponsor, but may receive salary or other support from the institution to support their effort on the projects(s). Dr. Neil Bressler is Principal Investigator of grants at The Johns Hopkins University or has agreements sponsored by the following entities (not including the National Institutes of Health): American Medical Association, Bayer, EMMES Corporation, Genentech, Novartis, and Regeneron. Adam R. Glassman: no disclosures.

References

- 1. [Accessed: March 11, 2012];National Diabetes Fact Sheet. 2011 Available at: < http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/factsheet11.htm>.

- 2.Varma R, Bressler NM, Doan Q, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic macular edema in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.2854. accepted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317(7160):703–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study report number 1. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103:1796–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elman MJ, Bressler NM, Qin H, et al. Expanded 2-year follow-up of ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:609–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elman MJ, Qin H, Aiello LP, et al. Intravitreal ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema with prompt versus deferred laser treatment: three-year randomized trial results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2312–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aiello LP, Beck RW, Bressler NM, et al. Rationale for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network treatment protocol for center-involved diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:e5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. [Accessed February 12, 2014];Diabetic Retinopathy PPP. 2012 Available at: http://one.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/diabetic-retinopathy-ppp--september-2008-4th-print.

- 9.Bressler NM, Varma R, Doan QV, et al. Underuse of the health care system by persons with diabetes mellitus and diabetic macular edema in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.6426. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]