ABSTRACT

Engineering microbial hosts for the production of fungible fuels requires mitigation of limitations posed on the production capacity. One such limitation arises from the inherent toxicity of solvent-like biofuel compounds to production strains, such as Escherichia coli. Here we show the importance of host engineering for the production of short-chain alcohols by studying the overexpression of genes upregulated in response to exogenous isopentenol. Using systems biology data, we selected 40 genes that were upregulated following isopentenol exposure and subsequently overexpressed them in E. coli. Overexpression of several of these candidates improved tolerance to exogenously added isopentenol. Genes conferring isopentenol tolerance phenotypes belonged to diverse functional groups, such as oxidative stress response (soxS, fpr, and nrdH), general stress response (metR, yqhD, and gidB), heat shock-related response (ibpA), and transport (mdlB). To determine if these genes could also improve isopentenol production, we coexpressed the tolerance-enhancing genes individually with an isopentenol production pathway. Our data show that expression of 6 of the 8 candidates improved the production of isopentenol in E. coli, with the methionine biosynthesis regulator MetR improving the titer for isopentenol production by 55%. Additionally, expression of MdlB, an ABC transporter, facilitated a 12% improvement in isopentenol production. To our knowledge, MdlB is the first example of a transporter that can be used to improve production of a short-chain alcohol and provides a valuable new avenue for host engineering in biogasoline production.

IMPORTANCE

The use of microbial host platforms for the production of bulk commodities, such as chemicals and fuels, is now a focus of many biotechnology efforts. Many of these compounds are inherently toxic to the host microbe, which in turn places a limit on production despite efforts to optimize the bioconversion pathways. In order to achieve economically viable production levels, it is also necessary to engineer production strains with improved tolerance to these compounds. We demonstrate that microbial tolerance engineering using transcriptomics data can also identify targets that improve production. Our results include an exporter and a methionine biosynthesis regulator that improve isopentenol production, providing a starting point to further engineer the host for biogasoline production.

INTRODUCTION

Isopentenol (3-methyl-3-buten-1-ol) is an important target compound as a precursor to pharmaceuticals, flavor compounds, such as prenol and isoamyl alcohol, and industrial chemicals, such as isoprene, and also for its tremendous potential as an immediately usable biofuel (1, 2). However, the microbial production of such compounds in bulk from renewable biomass is challenging, especially when considering the required yields for an economically viable process. Isopentenol production in Escherichia coli has been reported to use two different metabolic routes: via the amino acid biosynthetic pathway (3) and by refactoring the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mevalonate pathway in E. coli (4–6). The reported titers for isopentenol production in E. coli using the heterologous yeast-based mevalonate pathway now range in the gram-per-liter scale (4, 6). The inherent toxicity of these solvent-like compounds to the host microbe may limit the titer as production titers approach toxic concentrations. The lower limit of short-chain-alcohol toxicity in E. coli ranges from 2 to 8 g liter−1 (7), concentrations too low to be industrially relevant. In order to achieve economically viable product titers, it is necessary to engineer production strains to tolerate high titers of the product. To our knowledge, no tolerance candidates for C5 alcohols have been reported to date.

Here we determined if improved isopentenol tolerance would lead to increased titers. Several recent reports of the microbial production of solvent-like compounds indicate the toxicity of these compounds to be a key limitation in obtaining desirable production levels (8, 9). Cellular transport specifically has emerged as a direct yet effective mechanism for improved tolerance and, where pertinent, production of solvent-like compounds. We have shown in previous studies that a highly effective strategy of using RND (resistance-nodulation-division) efflux pumps for solvent tolerance may not be applicable to shorter-chain alcohols (7). Other classes of pumps have been discovered and described for tolerance engineering of aromatic acids, terpenes, and ionic liquids (10–12) but have not been evaluated for short-chain alcohols.

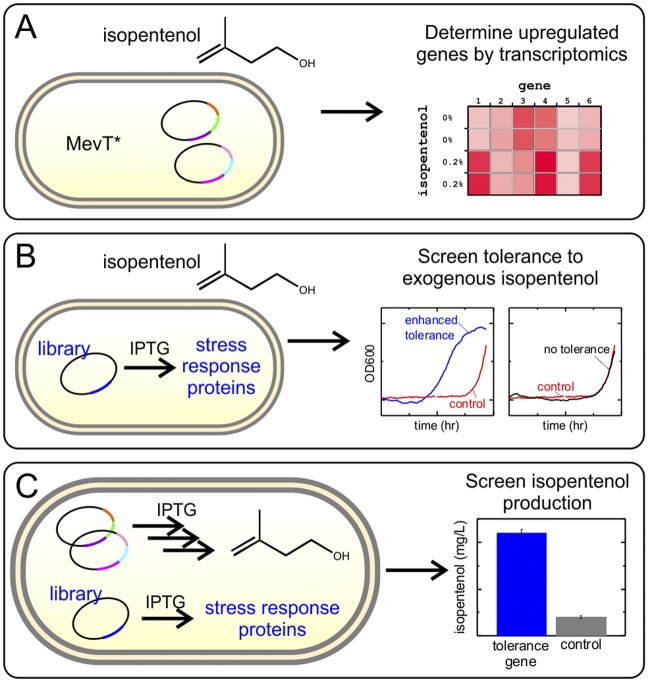

Functional genomics measurements reveal a large number of responses to toxic compounds, including many other modes of alleviating solvent stress (13, 14). Due to the promise of utilizing systems biology to engineer alcohol-tolerant strains (15), we used transcriptomics data to identify genes that may serve as candidates for tolerance engineering for isopentenol. Whole-genome transcriptomics revealed several genes that were responsive to exogenous isopentenol (Fig. 1A). We then tested the efficacies of the most highly induced candidates to improve tolerance to exogenous isopentenol (Fig. 1B). The candidates that successfully alleviated growth lag when overexpressed in the presence of isopentenol were then integrated with an isopentenol production strain (Fig. 1C) (6). Several candidate genes improved isopentenol tolerance, and one candidate, MetR, improved the isopentenol titer by 55%. The putative ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter MdlB increased the titer by 12% and is, to our knowledge, the first example of an exporter that has improved the titer of a short-chain alcohol. The knowledge of even one such transporter for a desirable final product can lead to considerable additional discoveries, such as bioprospecting for homologs (7) and utilizing directed evolution (12, 16). These results demonstrate the importance of utilizing transcriptomics data for improving short-chain alcohol production as a guide for host engineering.

FIG 1 .

Scheme for screening tolerance and increasing titer of isopentenol. (A) First, transcriptomics of E. coli DH1 expressing an inactive mevalonate pathway (MevT*; see Materials and Methods) in the presence of exogenous isopentenol was used to determine what genes are upregulated in response to isopentenol stress. (B) A library of those genes was overexpressed in the presence of exogenous isopentenol. Growth curves were used to measure enhanced tolerance. (C) Finally, genes that conferred tolerance were tested for their ability to increase the isopentenol titer in a production strain.

RESULTS

Identification of E. coli genes that confer tolerance to isopentenol.

An E. coli isopentenol production strain with an inactive mevalonate-based isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway due to a mutation in the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-coenzyme A (CoA) synthase (17, 18) was treated with 0.2% (wt/vol) isopentenol. Changes in transcriptional levels of the genes in response to isopentenol stress were determined by microarray analysis. The distribution of COGs (clusters of orthologous groups) and the top 100 up- and top 100 down-regulated genes are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Forty of the top hundred significantly upregulated genes (log2 value > 1.9) were selected for further evaluation in improving isopentenol tolerance (see Table S2). The gene candidates were cloned into pBbA5k for overexpression using the Plac promoter to investigate their potential in improving isopentenol tolerance in E. coli DH1.

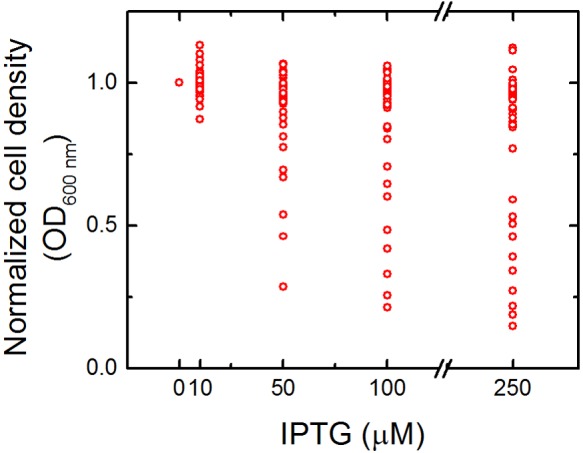

The expression burden of the 40 candidates expressed using medium-copy-number pBbA5k (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) was evaluated to avoid potential protein expression toxicity in the host. At 50 µM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and greater, a subset of strains showed decreased final cell density after 21 h of growth, indicating expression toxicity (Fig. 2; see also Fig. S1). Thus, 10 µM IPTG was chosen as a suitable induction concentration to reduce potential protein toxicity in subsequent tolerance analysis.

FIG 2 .

Induction of tolerance genes is toxic above 10 µM IPTG. E. coli DH1 harboring each of the 40 genes cloned into pBbA5k was induced with 0, 10, 50, 100, and 250 µM IPTG and grown for 21 h. For each strain, the OD600 was measured and normalized to growth without IPTG. The only concentration of IPTG that did not decrease growth across all strains was 10 µM IPTG; thus, all subsequent tolerance assays were performed with 10 µM IPTG. For OD600 data for a specific strain, see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

The control strain, E. coli DH1 harboring pBbA5k-rfp (red fluorescent protein [RFP]), was used to determine the concentration of isopentenol to be used for growth impact assays. The growth rate of the control strain was measured with exposure to 0 to 0.3% (wt/vol) isopentenol. The MIC was determined to be 0.24% (wt/vol) isopentenol for DH1 pBbA5k-rfp (Fig. 3A). In addition to slowing the growth rate, isopentenol lengthened the growth lag (Fig. 3B). The addition of 0.15% (wt/vol) exogenous isopentenol caused a sufficient change in growth rate and lag, and thus 0.15% (wt/vol) exogenous isopentenol was used for all subsequent growth impact assays.

FIG 3 .

Addition of isopentenol decreases the growth rate and causes growth lag. (A) Maximum growth rates (μmax) of DH1 pBbA5k-rfp induced with 10 µM IPTG were determined with exposure to 0 to 0.3% (wt/vol) isopentenol. Error bars represent standard errors from at least 4 replicates. The MIC under these growth conditions is 0.24% (wt/vol) isopentenol. (B) Representative growth curves of E. coli DH1 harboring pBbA5k-rfp induced with 10 µM IPTG and grown in the presence of 0% (wt/vol), 0.10% (wt/vol), 0.15% (wt/vol), and 0.20% (wt/vol) isopentenol. The addition of 0.15% exogenous isopentenol caused a sufficient lag in growth recovery, and thus 0.15% isopentenol was chosen as the concentration of isopentenol for tolerance assays.

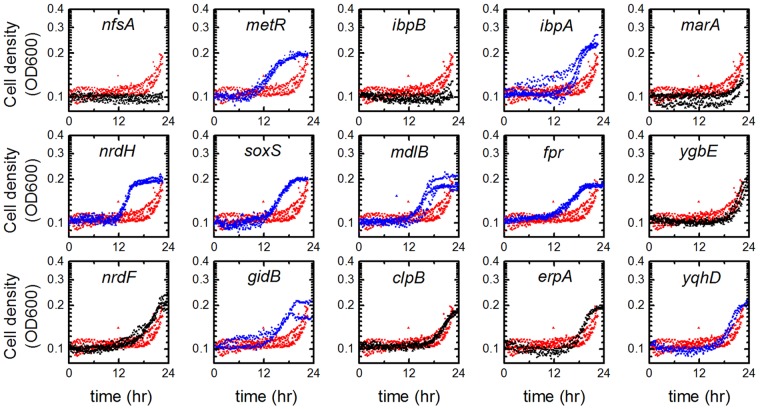

Growth impact assays of the 40 strains overexpressing the tolerance candidates revealed many strains with reduced growth lag compared to that of the control strain in the presence of 0.15% (wt/vol) isopentenol (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The strains that demonstrated shortened growth lag in the initial screen were assayed again in triplicate (Fig. 4). The eight genes that reduced the isopentenol-related growth lag were metR, ibpA, nrdH, soxS, mdlB, fpr, gidB, and yqhD.

FIG 4 .

Eight gene candidates demonstrated tolerance to 0.15% (wt/vol) isopentenol. Strains that demonstrated isopentenol tolerance in the initial screen were screened in triplicate for their tolerance to 0.15% (wt/vol) isopentenol (black or blue) in comparison to an rfp-expressing strain (red traces). The eight genes that conferred the greatest growth lag shortening, shown in blue, are metR, ibpA, nrdH, soxS, mdlB, fpr, gidB, and yqhD.

The majority of tolerance-conferring genes increase isopentenol production.

Next, we tested the potential of the tolerance-conferring genes to improve isopentenol production. To avoid plasmid compatibility issues upon cotransformation with the isopentenol pathway plasmids (specifically, pJBEI-6830 [6]), the confirmed tolerance genes were subcloned into a low-copy-number plasmid, pBbS5k, prior to transformation into the production strain. The isopentenol production pathway is induced with a high IPTG concentration (500 µM IPTG) (6); however, the tolerance-conferring genes expressed on the medium-copy plasmid pBbA5k had demonstrated toxicity when induced with as little as 50 µM IPTG (Fig. 2). DH1 harboring only the tolerance-enhancing genes on the low-copy-number plasmid pBbS5k was tested for toxicity when induced with 500 µM IPTG (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). These strains grew similarly to the RFP-expressing control strain and thus allowed the use of the 500 µM concentration of IPTG required for isopentenol induction without the previously measured toxicity that had been observed during candidate tolerance protein expression (see Fig. S3).

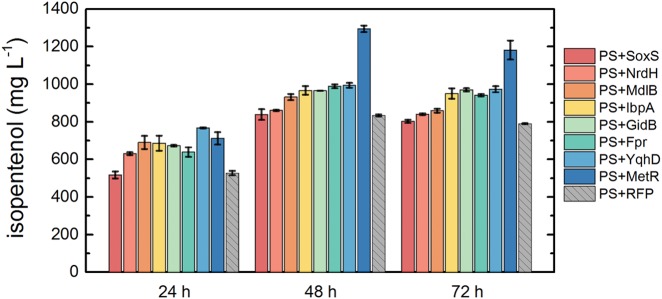

The eight genes with confirmed tolerance phenotypes were individually expressed in an isopentenol production strain, specifically E. coli DH1 harboring the isopentenol production plasmids pJBEI-6830 and pJBEI-6833 (6), here referred to as the production strain (PS). Production strains coexpressing a given tolerance gene on pBbS5k are here referred to as PS+[gene product]. These strains were induced over a range of IPTG concentrations to determine the dose-response effect of induction on titer. The maximum titer for most strains plateaued after 500 µM IPTG; thus, all subsequent production strains were induced with 500 µM IPTG (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The production of isopentenol was quantified in triplicate for all PS strains at 24, 48, and 72 h after 500 µM IPTG induction (Fig. 5). The PS strain coexpressing RFP on the pBbS5k plasmid (PS+RFP) was used as a titer control. Production of isopentenol was highest at 48 h after induction, after which the quantity of isopentenol in the cultures decreased slightly, likely due to volatility (Fig. 5). At the 48-h time point, the isopentenol titer in the PS+SoxS and PS+NrdH strains were statistically similar to that of PS+RFP. The remaining 6 strains show an increase in the isopentenol titer over that of the PS+RFP control, producing 12 to 55% more isopentenol after 48 h (Fig. 5 and Table 1).

FIG 5 .

MetR increases production of isopentenol by 55%. The eight tolerance genes were individually coexpressed with the isopentenol production pathway. The tolerance genes and the production pathway were simultaneously induced with 500 µM IPTG in triplicate, and the isopentenol concentration was measured 24, 48, and 72 h after induction. The production strain coexpressing metR (PS+MetR) improved the isopentenol titer 55% over that for the rfp-expressing strain (PS+RFP).

TABLE 1 .

Isopentenol tolerance-enhancing genes

| Gene | Description | Microarray log2, z score | Isopentenol production (mg liter−1)a | Improvement in titer (%)b | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| soxS | DNA-binding transcriptional dual regulator | 3.51, 2.81 | 838 ± 29 | 0 | 28, 42, 43 |

| nrdH | Glutaredoxin-like protein | 2.17, 2.08 | 860 ± 3 | 3 | 44 |

| mdlB | Predicted multidrug ABC transporter | 3.75, 2.31 | 931 ± 16 | 12 | 25 |

| ibpA | Heat shock chaperone | 4.80, 2.82 | 967 ± 23 | 16 | 26, 27 |

| gidB | Glucose-inhibited division protein B | 5.32, 2.64 | 965 ± 1 | 16 | 29, 45, 46 |

| fpr | Ferredoxin-NADP reductase | 2.30, 2.07 | 989 ± 10 | 19 | 28 |

| yqhD | Alcohol dehydro-genase, NAD(P) dependent | 2.40, 2.39 | 994 ± 13 | 19 | 14, 30, 31 |

| metR | DNA-binding transcriptional activator | 2.57, 2.55 | 1,290 ± 20 | 55 | 32, 33 |

Averages from triplicates after 48 h.

Percent improvement in titer is in comparison to result for PS+RFP at 48 h (834 ± 5 mg liter−1).

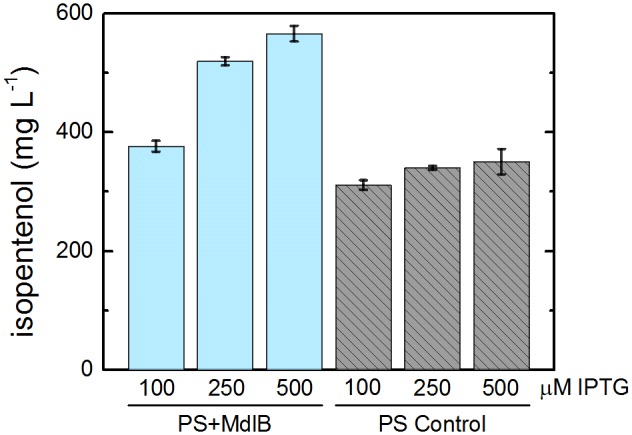

Transporters have emerged as a powerful and simple mechanism to engineer tolerance toward solvent-like molecules (7, 16). The putative ABC transporter MdlB (expressed by PS+MdlB) increased isopentenol titer by 12% over that of the control strain (PS+RFP). To determine if the effect of MdlB was titratable, the titer was measured for PS+MdlB and PS+RFP over a range of IPTG concentrations after 25 h. In this time frame, all IPTG concentrations produced statistically similar titers; thus, we infer that any change in the titer produced by PS+MdlB is due to increasing levels of MdlB. PS+MdlB produced more isopentenol than the control strain at all IPTG concentrations (Fig. 6), increasing the titer over that for the control strain by about 20%, 50%, and 60% when induced with 100 µM, 250 µM, and 500 µM IPTG, respectively.

FIG 6 .

The putative ABC transporter MdlB increases isopentenol production. The isopentenol titer was measured in triplicate in PS+MdlB and PS+RFP over a range of IPTG concentrations to determine if the increase in production is titratable. Isopentenol titer is significantly increased in PS+MdlB at 100 µM, 250 µM, and 500 µM IPTG (P value =8 × 10−4, 2 × 10−6, and 1 × 10−4, respectively, two-sided t test).

mdlB but not metR is specific to isopentenol tolerance.

MdlB and MetR are particularly interesting because both methionine biosynthesis regulation and pumps have been implicated as candidates to improve tolerance to other alcohols (7, 19–21). To determine specificity, we investigated if MdlB or MetR conferred tolerance to other short-chain alcohols. While MdlB and MetR expression reduced the growth lag in the presence of isopentenol, the alternate alcohols did not cause a growth lag, and thus the growth rate was used as a metric for tolerance (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Expression of MdlB did not improve the growth rate or final cell density for any other alcohol tested. Expression of MetR slightly improved the growth rate in the presence of ethanol and butanol by 2.5 and 15% (see Fig. S5). This suggests that the mechanism for MdlB improving isopentenol tolerance is specific to isopentenol but that MetR may have broader applications in improving alcohol tolerance.

DISCUSSION

Systems biology can play an important role in metabolic and host engineering. In the past decade, a growing number of reports have successfully used genome-wide methods to discover and utilize pathways, genes, and regulatory mechanisms to obtain superior host platforms or to optimize metabolic pathways. Ranging from genome-wide response changes implemented using altered (22) or heterologous (23) regulators to recombineering-based genome editing (24), there are powerful methods to develop host microbes with a desirable phenotype that complements bioproduction pathways. Traditional transcriptomics remains part of this toolbox and has been used extensively to understand cellular responses to final products that are also stressors (13–15). However, candidates that show high differential expression in response to these compounds may not necessarily improve tolerance (15). Increased tolerance also may not correspond invariably with increased production. Therefore, most candidates shortlisted from such efforts must be examined further for their efficacy in improving tolerance and production.

Studies of E. coli stress responses to other alcohols, such as n-butanol, have shown that short-chain alcohols primarily cause protein misfolding, cell envelope stress, and oxidative stress (14). The most highly responsive candidates during isopentenol exposure spanned several functional categories. Upregulated genes were dominated by chaperones (ibpA and ibpB), redox and energy balance genes (soxS, frmB, nrdH, and yqhD), and membrane proteins (mdlB, tauC, and mdtC). Several transcriptional factors, some of which are known to regulate genes in response to solvent tolerance, were also upregulated (marA, yqhC, and metR). The transcriptomics in response to exogenous isopentenol are summarized in the supplementary section (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Of the 100 upregulated candidates (log2 value > 1.9), 40 candidates, distributed over several functional groups, were selected for further evaluation. The selected candidates included proteins involved in oxidative stress relief, RNA/DNA repair and synthesis (e.g., ribonucleotide reductase and redox coenzymes), the prevention and refolding of misfolded protein (e.g., heat shock proteins and chaperones), transport, metabolism, and growth, as well as several hypothetical proteins (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Of the 40 candidates screened, 8 candidates were found to confer tolerance to exogenously added isopentenol: metR, ipbA, nrdH, soxS, mdlB, fpr, gidB, and yqhD. Table 1 and also Text S1 in the supplemental material briefly describe the native functions of these genes. These genes were then overexpressed in an isopentenol production strain (6) to determine if any genes that conferred tolerance also improved the isopentenol titer (Fig. 5). Since the tolerance phenotype was selected using the exogenous addition of isopentenol, a priori, it is challenging to predict the candidates that may also have an impact on production.

The tolerance genes that did not increase production of isopentenol were soxS and nrdH. The overexpression of these genes allowed the strain to recover from the sudden high concentration of exogenously added isopentenol (Fig. 4), which suggests that the resulting proteins are directly or indirectly involved in ameliorating isopentenol stress. However, the lack of corresponding change in production suggests that the mechanisms by which these candidates function may not impose a net impact on the efficiency of the pathway or the flux of carbon toward this final product (Fig. 5).

The genes that increased both tolerance and isopentenol production were mdlB, ibpA, gidB, fpr, yqhD, and metR (Fig. 4 and 5). Broadly, these genes have been implicated in stress response or cellular repair mechanisms. MdlB is a predicted multidrug transporter subunit of the ABC transporter superfamily (25). IbpA is a heat shock protein and a molecular chaperone (26, 27). GidB is glucose-inhibited division protein B and is induced under stress conditions known to stimulate ppGpp accumulation (28, 29). Fpr is a ferredoxin-NADP reductase and contributes to damage repair during the SoxRS response of E. coli (28). YqhD is an NADPH-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase that has been implicated in increased titers of other biofuel candidates (14, 30, 31). The most notable increase in titer was observed with the overexpression of MetR. MetR is an activator of MetE and MetH of the methionine synthesis pathway (32). Inactivation of MetE by oxidative stress has been reported to result in methionine auxotrophy (33). Based on the reported roles of these genes, no one function may be universally applied to engineering strains to increase the isopentenol titer. Rather, this subset of proteins demonstrates the importance of screening libraries of potential candidates for improving both tolerance and titers.

MdlB is, to our knowledge, the first native pump that has been shown to increase both tolerance and production of short-chain alcohols (Fig. 6) (7). The native function and regulation of MdlB are largely unknown. A survey of existing gene array data for E. coli (Ecogene 3.0 [34]) indicates that MdlB is typically upregulated in response to antibiotics such as novomycin or mutations such as ΔgyrB that uncoil DNA (35). Short-chain alcohols may passively diffuse through the membrane, making them difficult targets for active export. Further investigation is required to determine the mechanism of MdlB improving the isopentenol titer, perhaps as a pump.

The availability of methionine is known to be limited under stress conditions, such as heat shock, oxidative stress, and solvent stress (19, 33, 36). Here, we have shown that MetR expression increases both isopentenol tolerance and titers (Fig. 5) and MetR slightly improves growth in the presence of butanol (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Methionine biosynthesis was shown to be upregulated in the presence of exogenous furfural, and it was proposed that inhibition of sulfur assimilation limited cysteine and methionine biosynthesis (19). Additionally, ethanol was shown to stall translation at nonstart AUG codons, proposed to be the cause of methionine auxotrophy under solvent stress (20). Furthermore, a deletion in the methionine biosynthesis repressor MetJ increased ethanol tolerance (20). Given that methionine biosynthesis regulation is altered under solvent stress, future work is required to determine amino acid dependence in an isopentenol production strain.

In conclusion, we used transcript level measurements to screen gene candidates that respond to a key biogasoline candidate, isopentenol. Using tolerance and production studies, we identified several genes that enhanced isopentenol tolerance and in some cases production. This strategy improved the isopentenol titer by up to 55%, and subsequent host engineering will focus on combining these genes for further improvement in the titer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, oligonucleotides, chemicals, and culture media.

See Table S3 in the supplemental material for a complete list of plasmids and strains used in this study. The host strain used for plasmid construction was E. coli DH10B (Invitrogen). For microarray studies of isopentenol tolerance, the MevT* strain [E. coli DH1 harboring pMevT(C159A), pMevB, and pC9b] was used. The MevT* strain expresses an inactive version of the mevalonate-based isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway due to a mutation in HMG-CoA synthase on pMevT(C159A) (17, 18). The MevT* strain also harbors pMevB (17, 18) and pC9b (5). All vectors in the MevT* strain are expressed on an IPTG-inducible lacUV5 promoter. For growth assays and isopentenol production, E. coli DH1 (ATCC 33849) was used. Gene candidates that could potentially improve isopentenol tolerance were cloned into the BioBrick vectors pBbA5k and pBbS5k (37). Both vectors have a lacUV5 promoter and kanamycin resistance marker, but the replication origins are p15A and SC101, respectively. The isopentenol production strains all harbor plasmids pJBEI-6830 and pJBEI-6833 (6). The mevalonate pathway genes were cloned into vectors pBbA5c and pTrc99A. This strain was transformed with tolerance-conferring genes cloned into vector pBbS5k for production assays. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (USA) (see Table S4). All strains used in this study are listed in Table S3. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) unless otherwise stated.

Luria broth (LB) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics was used during cell cultivation for plasmid construction and preparation of precultures for cell adaptation in minimal medium. Growth assays were performed in M9 minimal medium, which consisted of 1× M9 salt (Difco), 2 mM MgSO4, 100 µM CaCl2, 0.5 mg liter−1 thiamine, and 0.4% glucose. Isopentenol production strains were grown in a modified M9 3-morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid (MOPS) minimal medium (MM9), which consisted of 1× M9 salt (Difco), 75 mM MOPS (pH 7.40, 2 mM MgSO4, 10 µM CaCl2, 10 µM FeSO4, 1× micronutrient, and 1% glucose. The 1× micronutrient was composed of 4 µM boric acid, 0.8 µM manganese chloride, 0.3 µM cobalt chloride, 0.15 µM cupric sulfate, 0.1 µM zinc sulfate, and 0.03 µM ammonium molybdate.

Where appropriate, chloramphenicol (50 µg ml−1), carbenicillin (100 µg ml−1), and kanamycin (15 µg ml−1 for isopentenol production or 30 µg ml−1 otherwise) were added to the medium.

Microarray sample preparation and data analysis.

E. coli DH1 MevT* was used to determine genes upregulated in the presence of exogenous isopentenol. The strain was grown in MM9 with 1% glucose, 2 mM Mg, and 0.5 mM IPTG and treated with 0% or 0.2% isopentenol added exogenously. Samples were collected at 150 min and 390 min after isopentenol addition. mRNA preparation and microarray analysis for whole-genome transcript response were performed as described previously (38).

Cloning and expression of genes.

Gene candidates to be tested for improving isopentenol tolerance were PCR amplified using E. coli MG1655 genomic DNA purified using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Life Bio, New York) as the template. The vector backbones and the sequences of the oligonucleotides used for amplifying the genes are listed in Table S4 in the supplemental material. J5 was used to design the assembly of the gene candidates into the vector backbones (39). The vector backbones were prepared by PCR amplification from pBbA5k-RFP and pBbS5k-RFP (37), using the oligonucleotides pBb5-F and pBb5-R. iProof high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Bio-Rad, California) was used for the PCRs according to the manufacturer’s recommendation.

The genes were cloned into the selected vectors by following an adapted Golden Gate protocol (40, 41). Specifically, for each cloning reaction, 50 ng of the vector backbone was mixed with an equimolar amount of the amplified gene fragment in a solution consisting of 1.5 µl 10× T4 DNA ligase reaction buffer (NEB), 0.15 µl bovine serum albumin (10 mg/ml; NEB), 1 µl BsaI (Fermentas), and 1 µl T4 DNA ligase (2000 cohesive end units/μl; NEB) and made up with deionized water to a final volume of 15 µl. The mixture was subjected to the following program for ligation: 25 cycles at 37°C for 3 min and 16°C at 4 min, followed by 1 cycle at 50°C for 5 min and 80°C for 5 min. DH10B chemically competent cells were transformed with 5 µl of the ligation reaction mixture and recovered in SOC (super optimal broth with catabolite repression) for 1 h at 37°C. The transformants were plated on LB-kanamycin agar plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. Single colonies were inoculated into LB-kanamycin and grown overnight at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Plasmids were isolated, and the genes were verified by DNA sequencing.

Transformation of cells and adaptation of cells to M9 minimal medium.

Plasmids expressing tolerance gene candidates were transformed into chemically competent E. coli DH1 containing the plasmids for isopentenol production, pJBEI-6830 and pJBEI-6833 (6), resulting in a three-plasmid-containing strain. The transformants were recovered in SOC medium (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 37°C and plated on LB agar supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics.

The strains were adapted to defined M9 minimal medium by subcultivating single colonies in minimal medium. Single colonies were inoculated into 5 ml LB medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics and were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking. The overnight cultures were diluted 100-fold in 5 ml minimal medium (M9 for the single-plasmid strains and MM9 for the production strains) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics and grown for 24 h at 37°C with shaking. Subcultivation was repeated twice more to fully adapt the cells. The adapted cells were centrifuged (3,000 × g, 2 min), resuspended in the respective minimal medium with 10% glycerol added, and stored at −80°C in 50-µl aliquots.

Effect of gene overexpression on strain growth.

For each strain harboring a single plasmid with the tolerance gene candidate cloned into pBbA5k, a 50-µl aliquot of adapted cells was inoculated into 2 ml M9 supplemented with kanamycin. The cultures were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking at 225 rpm. The cells were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ~0.05 in fresh M9-kanamycin with 0, 10, 50, 100, or 250 µM IPTG. The plates were sealed with breathable clear film (Thermo Scientific) and grown for 21 h at 37°C with shaking at 225 rpm. The OD600 of the cultures was read on a microplate reader (SpectraMax M2; Molecular Devices).

Impact of gene candidates on isopentenol tolerance.

Precultures were prepared as described in the previous section and diluted to an OD600 of ~0.05 in fresh M9-kanamycin with 10 µM IPTG and 0 to 0.3% (wt/vol) isopentenol, as indicated. All growth curves were measured in 24-well plates sealed with breathable clear film (Thermo Scientific), and the OD600 was measured every 10 min while the cells were grown for 24 h at 37°C with shaking in a microtiter plate reader (Tecan Infinite F200). The MIC of isopentenol was determined by calculating the maximum growth rate for at least 4 growth curves per concentration of isopentenol. Subsequent isopentenol growth impact experiments were performed using 0.15% (wt/vol).

Isopentenol production titer in whole culture.

Precultures of the production strains were prepared as described in the previous section in MM9 minimal medium supplemented with the appropriated antibiotics and diluted to an OD600 of ~0.08 in 5 ml of fresh medium. The cultures were grown at 37°C with shaking until an OD600 of ~0.4 was reached. Expression of the production and tolerance genes was then simultaneously induced with 500 µM IPTG. The cultures were subsequently grown at 30°C with shaking for isopentenol production. After 24, 48, and 72 h of induction, 200-µl aliquots of the cultures were extracted using 200 µl ethyl acetate (with 10 mg liter−1 n-butanol as an internal standard), and the organic extracts were diluted 5-fold with ethyl acetate before they were analyzed by gas chromatography, as described previously (2), to quantify the isopentenol production titer. IPTG dose-response experiments were performed similarly using 100, 250, 500, or 1,000 µM IPTG.

Tolerance to other alcohols.

Precultures were prepared as described in previous sections and diluted to an OD600 of ~0.08 in fresh M9-kanamycin with 10 µM IPTG and an alcohol of interest. The alcohols chosen and the concentrations used were as follows: ethanol at 3% (vol/vol), n-butanol at 0.7% (vol/vol), n-pentanol at 0.15% (vol/vol), isopropanol at 2% (vol/vol), isobutanol at 0.8% (vol/vol), and isopentanol at 0.25% (vol/vol). The inhibitory concentrations were derived from previous reports (7, 16). The plates were sealed with breathable clear film (Thermo Scientific), and the OD600 was measured every 20 min while the cells were grown for 18 h at 37°C with shaking in a microtiter plate reader (Tecan Infinite F200). Maximum growth rates were calculated for each growth curve.

Microarray data accession number.

Complete data obtained in this work are available in the GEO database under accession number GSE53138 and at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE53138.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental Materials and Methods. Download

Expression of select tolerance library genes is toxic when induced with 50 µM or more IPTG. E. coli DH1 harboring plasmids of the 40 genes in pBbA5k was induced with 0, 10, 50, 100, and 250 µM IPTG and grown for 21 h. For each strain, the OD600 was measured and normalized to that for growth without IPTG. In this color map, genes are ordered in increasing OD600 for the 50 µM IPTG condition. The only condition that did not significantly change the final OD600 across all cultures was 10 µM IPTG, for which it ranged from 0.87 (mdtG) to 1.1 (yhcN). Thus, we performed all following experiments with pBbA5k at 10 µM IPTG to ensure that expression of the tolerance gene was not toxic. Download

Growth curves of all 40 candidates reveal 8 potential targets for improved tolerance. The 40 genes were individually overexpressed in E. coli DH1 with 10 µM IPTG and grown in the presence of 0.15% (wt/vol) isopentenol. The growth of the strains (black) was monitored in two sets over 24 h (A) or 48 h (B). The tolerance strains were compared to the control strain expressing RFP (gray) from the same growth condition. Strains with growth lags shorter than that of the control were selected for secondary selection. Download

Inducing the eight selected tolerance genes in the low-copy-number pBbS5k vector with 500 µM IPTG does not cause significant toxicity. The growth curves of the selected eight tolerance-enhancing genes (black) show that overexpression with 500 µM IPTG does not significantly alter growth compared to that of the rfp-expressing strain (red). Only metR and mdlB are associated with a slight defect in growth. Swapping the tolerance-enhancing genes into the low-copy-number pBbS5k plasmid backbone allows for the high IPTG concentration necessary for isopentenol production without significant toxicity. Download

Dose-response relationship of inducer to isopentenol titer shows a plateau in titer after 500 µM IPTG. Production strains coexpressing tolerance genes were induced over a range of IPTG concentrations to determine the maximum titer for each strain. The titer plateaued for most strains between 500 and 1,000 µM IPTG after 48 h; thus, all subsequent production strains were induced with 500 µM IPTG. Download

MetR and MdlB specifically confer tolerance to isopentenol. MdlB (blue), MetR (orange), and RFP (red) were overexpressed on pBbA5k in E. coli DH1 with 10 µM IPTG and grown in the presence of other alcohols in triplicate. The RFP growth curve with no alcohol added is shown in grey. (A) MdlB did not improve the growth rate when grown in the presence of any of the alcohols tested. (B) The growth rates of pBbA5k-rfp and pBbA5k-metR in the presence of ethanol are 0.151 ± 0.001 h−1 and 0.155 ± 0.001 h−1, respectively. The growth rates of pBbA5k-rfp and pBbA5k-metR in the presence of butanol are 0.103 ± 0.004 h−1 and 0.119 ± 0.007 h−1, respectively. MetR statistically improved the growth rate in the presence of ethanol by 2.5% and that in the presence of butanol by 15% (P = 0.008 and 0.03, respectively; two-sided t test). Growth of the RFP-expressing control strain in the absence of alcohol is indicated by “RFP no –OH.” Download

Description of microarray GEO GSE53138

Genes selected for cloning to investigate their abilities to confer isopentenol tolerance

Plasmids and strains

Sequences of oligonucleotides used in plasmid construction of tolerance genes

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nathan Hillson and Victor Chubukov for helpful discussions and Kim Ho for generating the Plac version of pMevT(C159A).

This work was part of the DOE Joint BioEnergy Institute partnership (http://www.jbei.org) supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, through contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 between Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the U.S. Department of Energy. Jee Loon Foo was supported by the Competitive Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Singapore (NRF-CRP5-2009-03).

Footnotes

Citation Foo JL, Jensen HM, Dahl RH, George K, Keasling JD, Lee TS, Leong S, Mukhopadhyay A. 2014. Improving microbial biogasoline production in Escherichia coli using tolerance engineering. mBio 5(6):e01932-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01932-14.

REFERENCES

- 1. Peralta-Yahya PP, Zhang F, del Cardayre SB, Keasling JD. 2012. Microbial engineering for the production of advanced biofuels. Nature 488:320–328. 10.1038/nature11478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chou HH, Keasling JD. 2012. Synthetic pathway for production of five-carbon alcohols from isopentenyl diphosphate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:7849–7855. 10.1128/AEM.01175-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cann AF, Liao JC. 2010. Pentanol isomer synthesis in engineered microorganisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85:893–899. 10.1007/s00253-009-2262-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zheng YN, Liu Q, Li LL, Qin W, Yang JM, Zhang HB, Jiang XL, Cheng T, Liu W, Xu X, Xian M. 2013. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for high-specificity production of isoprenol and prenol as next generation of biofuels. Biotechnol. Biofuels 6:57. 10.1186/1754-6834-6-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Withers ST, Gottlieb SS, Lieu B, Newman JD, Keasling JD. 2007. Identification of isopentenol biosynthetic genes from Bacillus subtilis by a screening method based on isoprenoid precursor toxicity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:6277–6283. 10.1128/AEM.00861-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. George KW, Chen A, Jain A, Batth TS, Baidoo EEK, Wang G, Adams PD, Petzold CJ, Keasling JD, Lee TS. 2014. Correlation analysis of targeted proteins and metabolites to assess and engineer microbial isopentenol production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 111:1–11. 10.1002/bit.25226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dunlop MJ, Dossani ZY, Szmidt HL, Chu HC, Lee TS, Keasling JD, Hadi MZ, Mukhopadhyay A. 2011. Engineering microbial biofuel tolerance and export using efflux pumps. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7:487. 10.1038/msb.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Atsumi S, Hanai T, Liao JC. 2008. Non-fermentative pathways for synthesis of branched-chain higher alcohols as biofuels. Nature 451:86–89. 10.1038/nature06450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yim H, Haselbeck R, Niu W, Pujol-Baxley C, Burgard A, Boldt J, Khandurina J, Trawick JD, Osterhout RE, Stephen R, Estadilla J, Teisan S, Schreyer HB, Andrae S, Yang TH, Lee SY, Burk MJ, Van Dien S. 2011. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for direct production of 1,4-butanediol. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7:445–452. 10.1038/nchembio.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Dyk TK, Templeton LJ, Cantera KA, Sharpe PL, Sariaslani FS. 2004. Characterization of the Escherichia coli AaeAB efflux pump: a metabolic relief valve? J. Bacteriol. 186:7196–7204. 10.1128/JB.186.21.7196-7204.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doshi R, Nguyen T, Chang G. 2013. Transporter-mediated biofuel secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:7642–7647. 10.1073/pnas.1301358110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Foo JL, Leong SS. 2013. Directed evolution of an E. coli inner membrane transporter for improved efflux of biofuel molecules. Biotechnol. Biofuels 6:81. 10.1186/1754-6834-6-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brynildsen MP, Liao JC. 2009. An integrated network approach identifies the isobutanol response network of Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5:277. 10.1038/msb.2009.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rutherford BJ, Dahl RH, Price RE, Szmidt HL, Benke PI, Mukhopadhyay A, Keasling JD. 2010. Functional genomic study of exogenous n-butanol stress in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:1935–1945. 10.1128/AEM.02323-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zingaro KA, Terry Papoutsakis E. 2013. GroESL overexpression imparts Escherichia coli tolerance to i-, n-, and 2-butanol, 1,2,4-butanetriol and ethanol with complex and unpredictable patterns. Metab. Eng. 15:196–205. 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fisher MA, Boyarskiy S, Yamada MR, Kong N, Bauer S, Tullman-Ercek D. 2013. Enhancing tolerance to short-chain alcohols by engineering the Escherichia coli AcrB efflux pump to secrete the non-native substrate n-butanol. ACS Synth. Biol. 3:30–40. 10.1021/sb400065q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kizer L, Pitera DJ, Pfleger BF, Keasling JD. 2008. Application of functional genomics to pathway optimization for increased isoprenoid production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:3229–3241. 10.1128/AEM.02750-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pitera DJ, Paddon CJ, Newman JD, Keasling JD. 2007. Balancing a heterologous mevalonate pathway for improved isoprenoid production in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 9:193–207. 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miller EN, Jarboe LR, Turner PC, Pharkya P, Yomano LP, York SW, Nunn D, Shanmugam KT, Ingram LO. 2009. Furfural inhibits growth by limiting sulfur assimilation in ethanologenic Escherichia coli strain LY180. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6132–6141. 10.1128/AEM.01187-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haft RJ, Keating DH, Schwaegler T, Schwalbach MS, Vinokur J, Tremaine M, Peters JM, Kotlajich MV, Pohlmann EL, Ong IM, Grass JA, Kiley PJ, Landick R. 2014. Correcting direct effects of ethanol on translation and transcription machinery confers ethanol tolerance in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111:E2576–E2585. 10.1073/pnas.1401853111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watanabe R, Doukyu N. 2014. Improvement of organic solvent tolerance by disruption of the lon gene in Escherichia coli. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 118:139–144. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alper H, Stephanopoulos G. 2007. Global transcription machinery engineering: a new approach for improving cellular phenotype. Metab. Eng. 9:258–267. 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pan J, Wang J, Zhou Z, Yan Y, Zhang W, Lu W, Ping S, Dai Q, Yuan M, Feng B, Hou X, Zhang Y, Ma R, Liu T, Feng L, Wang L, Chen M, Lin M. 2009. IrrE, a global regulator of extreme radiation resistance in Deinococcus radiodurans, enhances salt tolerance in Escherichia coli and Brassica napus. PLoS One 4:e4422. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boyle NR, Reynolds TS, Evans R, Lynch M, Gill RT. 2013. Recombineering to homogeneity: extension of multiplex recombineering to large-scale genome editing. Biotechnol. J. 8:515–522. 10.1002/biot.201200237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Allikmets R, Gerrard B, Court D, Dean M. 1993. Cloning and organization of the abc and mdl genes of Escherichia coli: relationship to eukaryotic multidrug resistance. Gene 136:231–236. 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90470-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laskowska E, Wawrzynów A, Taylor A. 1996. IbpA and IbpB, the new heat-shock proteins, bind to endogenous Escherichia coli proteins aggregated intracellularly by heat shock. Biochimie 78:117–122. 10.1016/0300-9084(96)82643-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kitagawa M, Miyakawa M, Matsumura Y, Tsuchido T. 2002. Escherichia coli small heat shock proteins, IbpA and IbpB, protect enzymes from inactivation by heat and oxidants. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:2907–2917. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Giró M, Carrillo N, Krapp AR. 2006. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and ferredoxin-NADP(H) reductase contribute to damage repair during the soxRS response of Escherichia coli. Microbiology 152:1119–1128. 10.1099/mic.0.28612-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Okamoto S, Tamaru A, Nakajima C, Nishimura K, Tanaka Y, Tokuyama S, Suzuki Y, Ochi K. 2007. Loss of a conserved 7-methylguanosine modification in 16S rRNA confers low-level streptomycin resistance in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 63:1096–1106. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pérez JM, Arenas FA, Pradenas GA, Sandoval JM, Vásquez CC. 2008. Escherichia coli YqhD exhibits aldehyde reductase activity and protects from the harmful effect of lipid peroxidation-derived aldehydes. J. Biol. Chem. 283:7346–7353. 10.1074/jbc.M708846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jarboe LR. 2011. YqhD: a broad-substrate range aldehyde reductase with various applications in production of biorenewable fuels and chemicals. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 89:249–257. 10.1007/s00253-010-2912-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maxon ME, Redfield B, Cai XY, Shoeman R, Fujita K, Fisher W, Stauffer G, Weissbach H, Brot N. 1989. Regulation of methionine synthesis in Escherichia coli: effect of the MetR protein on the expression of the metE and metR genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:85–89. 10.1073/pnas.86.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hondorp ER, Matthews RG. 2004. Oxidative stress inactivates cobalamin-independent methionine synthase (MetE) in Escherichia coli. PLoS Biol. 2:e336. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou J, Rudd KE. 2013. EcoGene 3.0. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:D613–D624. 10.1093/nar/gks1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peter BJ, Arsuaga J, Breier AM, Khodursky AB, Brown PO, Cozzarelli NR. 2004. Genomic transcriptional response to loss of chromosomal supercoiling in Escherichia coli. Genome Biol. 5:R87. 10.1186/gb-2004-5-11-r87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gur E, Biran D, Gazit E, Ron EZ. 2002. In vivo aggregation of a single enzyme limits growth of Escherichia coli at elevated temperatures. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1391–1397. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee TS, Krupa RA, Zhang F, Hajimorad M, Holtz WJ, Prasad N, Lee SK, Keasling JD. 2011. BglBrick vectors and datasheets: a synthetic biology platform for gene expression. J. Biol. Eng. 5:12. 10.1186/1754-1611-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Joshua CJ, Dahl R, Benke PI, Keasling JD. 2011. Absence of diauxie during simultaneous utilization of glucose and xylose by Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. J. Bacteriol. 193:1293–1301. 10.1128/JB.01219-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hillson NJ, Rosengarten RD, Keasling JD. 2011. j5 DNA assembly design automation software. ACS Synth. Biol. 1:14–21. 10.1021/sb2000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Engler C, Gruetzner R, Kandzia R, Marillonnet S. 2009. Golden gate shuffling: a one-pot DNA shuffling method based on type IIs restriction enzymes. PLoS One 4:e5553. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Engler C, Kandzia R, Marillonnet S. 2008. A one pot, one step, precision cloning method with high throughput capability. PLoS One 3:e3647. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu J, Weiss B. 1991. Two divergently transcribed genes, soxR and soxS, control a superoxide response regulon of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173:2864–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Eaves DJ, Ricci V, Piddock LJ. 2004. Expression of acrB, acrF, acrD, marA, and soxS in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium: role in multiple antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1145–1150. 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1145-1150.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jordan A, Aslund F, Pontis E, Reichard P, Holmgren A. 1997. Characterization of Escherichia coli NrdH. A glutaredoxin-like protein with a thioredoxin-like activity profile. J. Biol. Chem. 272:18044–18050. 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Romanowski MJ, Bonanno JB, Burley SK. 2002. Crystal structure of the Escherichia coli glucose-inhibited division protein B (GidB) reveals a methyltransferase fold. Proteins 47:563–567. 10.1002/prot.10121.abs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Benítez-Páez A, Villarroya M, Armengod ME. 2012. Regulation of expression and catalytic activity of Escherichia coli RsmG methyltransferase. RNA 18:795–806. 10.1261/rna.029868.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Materials and Methods. Download

Expression of select tolerance library genes is toxic when induced with 50 µM or more IPTG. E. coli DH1 harboring plasmids of the 40 genes in pBbA5k was induced with 0, 10, 50, 100, and 250 µM IPTG and grown for 21 h. For each strain, the OD600 was measured and normalized to that for growth without IPTG. In this color map, genes are ordered in increasing OD600 for the 50 µM IPTG condition. The only condition that did not significantly change the final OD600 across all cultures was 10 µM IPTG, for which it ranged from 0.87 (mdtG) to 1.1 (yhcN). Thus, we performed all following experiments with pBbA5k at 10 µM IPTG to ensure that expression of the tolerance gene was not toxic. Download

Growth curves of all 40 candidates reveal 8 potential targets for improved tolerance. The 40 genes were individually overexpressed in E. coli DH1 with 10 µM IPTG and grown in the presence of 0.15% (wt/vol) isopentenol. The growth of the strains (black) was monitored in two sets over 24 h (A) or 48 h (B). The tolerance strains were compared to the control strain expressing RFP (gray) from the same growth condition. Strains with growth lags shorter than that of the control were selected for secondary selection. Download

Inducing the eight selected tolerance genes in the low-copy-number pBbS5k vector with 500 µM IPTG does not cause significant toxicity. The growth curves of the selected eight tolerance-enhancing genes (black) show that overexpression with 500 µM IPTG does not significantly alter growth compared to that of the rfp-expressing strain (red). Only metR and mdlB are associated with a slight defect in growth. Swapping the tolerance-enhancing genes into the low-copy-number pBbS5k plasmid backbone allows for the high IPTG concentration necessary for isopentenol production without significant toxicity. Download

Dose-response relationship of inducer to isopentenol titer shows a plateau in titer after 500 µM IPTG. Production strains coexpressing tolerance genes were induced over a range of IPTG concentrations to determine the maximum titer for each strain. The titer plateaued for most strains between 500 and 1,000 µM IPTG after 48 h; thus, all subsequent production strains were induced with 500 µM IPTG. Download

MetR and MdlB specifically confer tolerance to isopentenol. MdlB (blue), MetR (orange), and RFP (red) were overexpressed on pBbA5k in E. coli DH1 with 10 µM IPTG and grown in the presence of other alcohols in triplicate. The RFP growth curve with no alcohol added is shown in grey. (A) MdlB did not improve the growth rate when grown in the presence of any of the alcohols tested. (B) The growth rates of pBbA5k-rfp and pBbA5k-metR in the presence of ethanol are 0.151 ± 0.001 h−1 and 0.155 ± 0.001 h−1, respectively. The growth rates of pBbA5k-rfp and pBbA5k-metR in the presence of butanol are 0.103 ± 0.004 h−1 and 0.119 ± 0.007 h−1, respectively. MetR statistically improved the growth rate in the presence of ethanol by 2.5% and that in the presence of butanol by 15% (P = 0.008 and 0.03, respectively; two-sided t test). Growth of the RFP-expressing control strain in the absence of alcohol is indicated by “RFP no –OH.” Download

Description of microarray GEO GSE53138

Genes selected for cloning to investigate their abilities to confer isopentenol tolerance

Plasmids and strains

Sequences of oligonucleotides used in plasmid construction of tolerance genes