Abstract

Escherichia coli swarmer cells coordinate their movement when confined in thin layers of fluid on agar surfaces. The motion and dynamics of cells, pairs of cells, and packs of cells can be recapitulated and studied in polymer microfluidic systems that are designed to constrain swarmer cell movement in thin layers of fluid between no-slip surfaces. The motion of elongated, smooth swimming E. coli cells in these environments reproduces the behavior of packs of cells observed at the leading edge of swarming communities and demonstrates the delicate balance between the physical dimensions of fluids and bacterial cell behavior.

Introduction

Escherichia coli is a model organism for studies of the biophysics, mechanics, and behavior of the movement of bacterial cells in bulk fluids.1 This rod-shaped bacterium (~ 2 μm long, 800 nm wide) uses multiple flagella oriented axially along the cell body to propel cells through bulk liquids at low Reynolds number at a velocity that approaches 20–30 μm s−1.2,3 The counterclockwise rotation of the flagella (as viewed from behind the cell) bundles these filaments, performs work on the surrounding fluid, and pushes the cell forward in a direction parallel to its long axis. The clockwise motion of flagella alters the structure of the bundle, reduces the linear velocity of cells, and causes them to ‘tumble’.

Bacteria however are typically not solitary organisms and in their native ecological habitats they form large, dense communities of cells in contact with or in close proximity to surfaces.4 The resulting cells may be physiologically and morphologically different from the same strains of cells grown in liquid culture in the lab. For example, in close contact with surfaces, many genera of motile bacteria use a mechanism referred to as ‘swarming’ to access new sources of nutrients, to increase the size of the community, and to colonize niches.5,6 The phenotype is evident when E. coli K12 strains are grown on low-percentage Eiken agar gels—the surface triggers their differentiation into swarmer cells, their movement through a thin layer of fluid on the polymer surface, and the formation of unique cellular patterns.7 Some bacteria, such as Proteus mirabilis, form swarming communities in which the coordination of swarmer cell behavior has been hypothesized to facilitate infections.8,9

Swarming colonies of different bacterial genera share several common dynamic characteristics: (1) the alignment of adjacent cells and their coordinated movement in multicellular rafts; (2) the low curvature of their trajectories; (3) the low frequency of cell tumbles; (4) the formation of dynamic, circular vortices of cells; and (5) the cooperative motility of cells across surfaces.5,6 Many of the physical forces and interactions that shape the collective motion in these communities have not been identified and characterized, in part because of limitations of available experimental techniques. Consequently, much of what we understand about this area of microbiology comes from theory, simulations, and models. New experimental systems are needed.

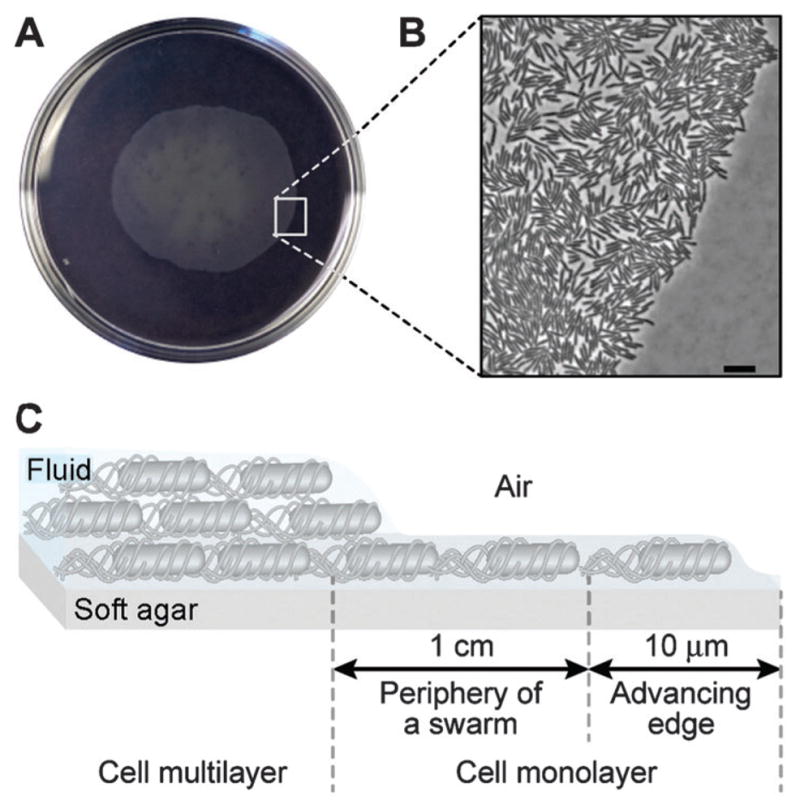

In this article, we study the coordination of vegetative E. coli cells swimming in thin layers of fluid that are structured to resemble the region at the periphery of swarming bacterial colonies (< 1 cm from the advancing edge). This region of a swarming colony consists of a monolayer of motile E. coli cells that assemble into transient, dynamic rafts (Fig. 1).10–12

Fig. 1.

Organization of an E. coli swarming colony. (A) An image of a swarming colony of E. coli strain MG1655 on the surface of a soft agar gel. The diameter of the Petri dish is 10 cm. (B) Higher magnification images depicting the advancing edge of the E. coli colony; scale bar = 10 μm. (C) A schematic diagram depicting the organization of cells in a swarming colony. Cells are in a monolayer at the periphery and advancing edge of the swarming community. Swarming cells in this region migrate through a thin film of fluid that is ~ 1 μm tall.

Two approaches have been described previously to study the dynamics of cells in similar physical regimes: (1) Sokolov et al. developed a mechanical system for drawing out thin films of fluid containing suspensions of bacteria;13 and (2) Wu and Libchaber studied bacteria in thin films of soap.14 We complement these studies by introducing an approach for studying interactions between planktonic and swarmer cells that is widely available to experimentalists and theorists, provides a stable environment for cell studies, and enables the user to control the height of fluid to recapitulate different regions within a swarming community of bacteria.15 We used a bottom-up approach by designing a microfluidic system in the optically transparent elastomer, poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) that confines motile E. coli cells in layers of fluid that were 1.7–5.0 μm tall. In addition to mimicking the height of the swarm at the edge of a colony, these channels position cells within approximately one imaging focal plane and enable us to quantitatively study the movement of cells at interfaces and interactions between cells using optical microscopy.

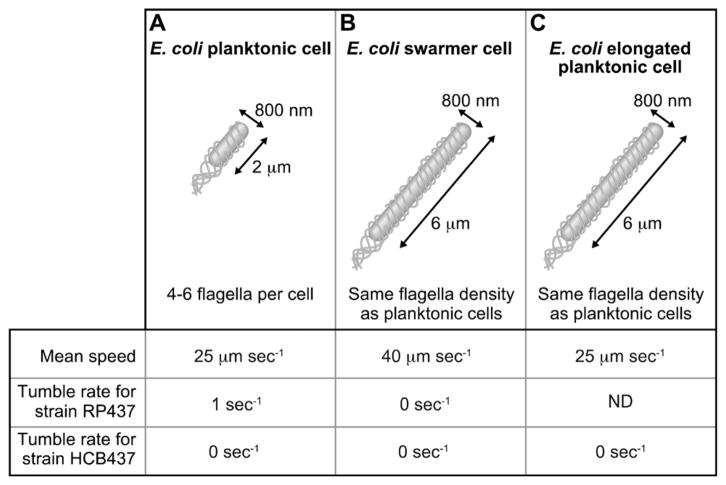

We manipulated vegetative E. coli cells to reproduce two of the most characteristic physical features of E. coli swarmer cells: cell length and tumble frequency (Fig. 2). By inhibiting cell division using the antibiotic cephalexin, we created E. coli cells with a length (mean length, 6.0 μm) that matched swarmer cells (mean length, 5.2 μm).7,16 To reproduce the low tumble frequency of E. coli swarmer cells, we used strain HCB437, in which the deletion of the chemosensory system yields smooth-swimming cells that do not tumble.17 This approach enabled us to avoid complications associated with growing and harvesting E. coli swarmer cells from plates and suspending them in fluids for motility studies. Using planktonic cells, we demonstrate that characteristic features of the motility and dynamics of swarmer cells at the edge of a colony can be captured in a suspension of elongated smooth-swimming E. coli cells confined in microfluidic environments.

Fig. 2.

Phenotypic comparison of E. coli cell motility parameters for: (A) planktonic cells (i.e., swimmer cells), (B) swarmer cells, and (C) elongated planktonic cells that were created by dosing cells with cephalexin. ‘ND’, not determined.

Results and discussion

Design of the microfluidic device and experimental conditions

We grew cells of E. coli HCB437 overnight at 37 °C in lysogeny broth (LB), consisting of: 1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 0.5% NaCl. We diluted the saturated culture 1:100 into 5 mL of tryptone broth (TB, Difco) and grew cells at 33 °C to an absorbance of 0.6 (λ = 600 nm), which indicated cells were at the mid-exponential phase of cell growth. As needed, we elongated E. coli cells by adding cephalexin (60 μg mL−1) to the cell culture at mid-exponential phase. The mean cell length was 6.0 μm after shaking the culture at 200 rpm for 20 min. We centrifuged cells at 4000 rpm for 5 min at 25 °C, and gently resuspended the cell pellet in motility buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM glucose, pH 7.0); we repeated this step twice.

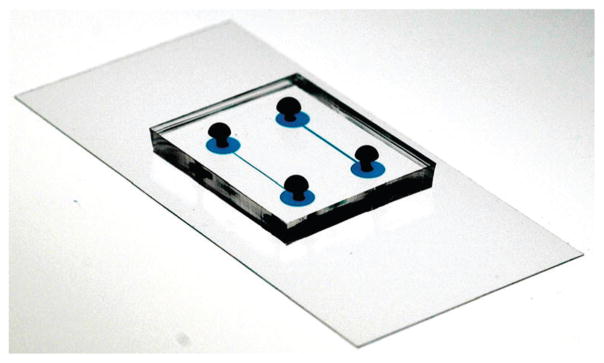

We imaged cells suspended in fluids in PDMS microfluidic channels created using soft lithography.18 Briefly, we used a Heidelberg mask writer to produce a mask for photolithography that consisted of a glass slide containing a pattern of chrome features that defined the microfluidic channels. We transferred the pattern from the photomask to a layer of photoresist using standard photolithography techniques. We spin-coated SU-8 photoresist 2002 or 2005 (Microchem) on a silicon wafer (Silicon Sense) at various angular velocities to create photoresist structures with a height that was 1.7–5 μm. Setting the angular velocity of the spin-coater enabled us to control the height of the photoresist layer, which defined the height of the microfluidic channels. We illuminated the photo-resist with UV light through the mask to cross-link specific regions of the polymer and dissolved the unexposed photoresist in the remaining areas using a solvent; the height of the photo-resist features were measured using a profilometer (Tencor Instruments Alpha Step 200). We cast PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning; 10:1 ratio of base:curing agent) on the master, cured it thermally, and peeled it away to reveal a layer of PDMS containing embossed microfluidic channels with defined height. We treated the PDMS layer with an oxygen plasma and bonded it to a glass coverslip coated with a thin layer of PDMS that had been oxidized in an oxygen plasma (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Picture of the microfluidic device. The device consists of two layers: a layer of PDMS containing the channels bonded to a glass slide covered with PDMS. The length of one channel is 1 cm and the channels were filled with blue dye to make them easy to visualize.

After bonding, we immediately filled the microfluidic channels with a solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA; 1% in PBS buffer) to decrease the adherence of cells to the surfaces of the channel. Before performing experiments, we replaced the BSA solution with motility buffer. We loaded a small volume of the suspension of elongated E. coli HCB437 cells into the PDMS device. We imaged bacteria using the 20× objective of a phase contrast microscope (Nikon Axioskop) equipped with a digital camera (Marshall Electronics MTV-1802CA) and analyzed cell trajectories using ImageJ.19

We configured several parameters of the device to ensure that the system was consistent with the physical constraints present during swarming. First, to mimic the thin layer of fluid near the edge of a swarming colony—where the liquid is 1–5 μm tall—we created PDMS microfluidic channels with a height that constrained cell motion in a thin layer of fluid (1.7–5.0 μm).20 We set the width of the channel at 200 μm to fit within the field of view of a 20× microscope objective.

Swarming cells move between agar–fluid and fluid–air interfaces. The interface of agar and fluid presents a no-slip surface. Air–fluid interfaces are typically slip surfaces and are not easily mimicked by the physical boundaries presented by materials, such as polymers.21 Zhang et al. demonstrated recently that the upper surface of an E. coli swarming colony is stationary and thus can be considered a no-slip boundary.22 To mimic swarmer cells between no-slip surfaces, we confined motile E. coli cells in a thin layer of liquid between two PDMS surfaces.

One complication of using channels, however is that motile vegetative and swarmer E. coli cells have a tendency to move close to surfaces,23–25 including along lateral walls in microfluidic systems, which changes the local concentration of cells over time.26 To avoid concentrating bacterial cells at the channel walls, we created serrated walls that projected cells toward the center of the channel by altering their trajectory (Fig. 4). We designed serrated projections with an angle, α which directed cells toward the center of the channel (α < 120°) and avoided trapping bacteria in the features (α > 80°).

Fig. 4.

Design of the PDMS microfluidic device. The serrated projections prevent the concentration of motile cells near the side walls. The characteristic dimensions of channels are defined using photolithography (here, channel length = 1 cm, channel width = 200 μm, and channel height = 2.5 μm). A typical trajectory of an E. coli cell swimming in close proximity to the wall is shown. Cells appear as black rods in the background (image acquired using phase contrast microscopy).

Behavior of a single swimming E. coli cell in the microfluidic device

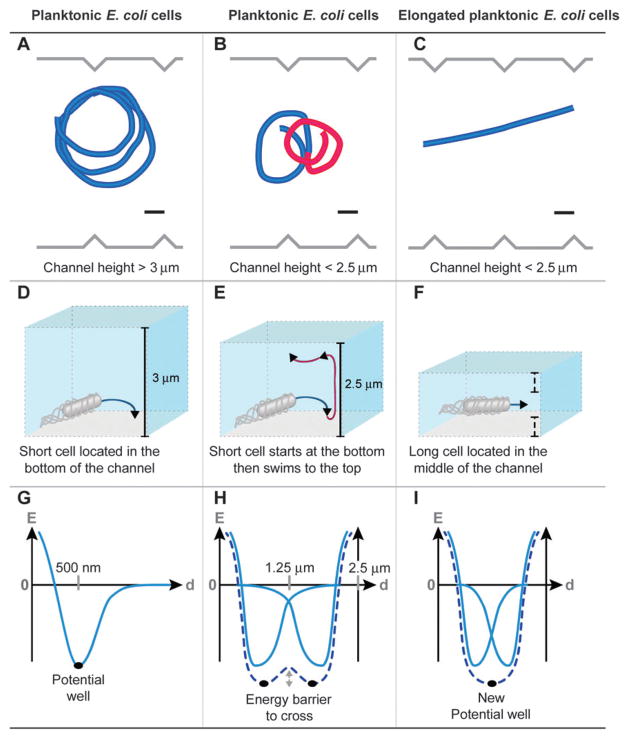

The behavior of swimming E. coli cells changed dramatically depending on the height of the channels. In the tallest channels we studied (height > 3 μm), the majority of cells moved in circular trajectories (Fig. 5A). The circular motion of bacterial cells at interfaces is well characterized.27–29 The counterclockwise rotation of flagella—as viewed from behind the cell—bundles the filaments and the torque created by this structure is balanced by the counter-rotation of the cell body at ~ 25 Hz.30 The rotation of the bundle and the opposite rotation of the cell body produce a characteristic circular motion in close proximity to surfaces (~ 100 nm) (Fig. 5D).31 The residence time of a cell swimming smoothly (i.e., not tumbling) near a surface is relatively long (~ 60 s),32 and is principally due to hydrodynamic forces between cells and surfaces, which creates a potential well (Fig. 5G).

Fig. 5.

Typical trajectories observed for E. coli HCB437 smooth-swimming cells in serrated microfluidic channels. Different cell trajectories are observed depending on the channel height and cell length: (A) a planktonic cell swimming in a characteristic circular trajectory in channels > 3 μm tall; (B) a planktonic cell swimming in a characteristic figure-eight pattern in channels < 2.5 μm tall; and (C) an elongated planktonic cell swimming in a characteristically straight trajectory in channels < 2.5 μm tall (scale bars = 10 μm). These trajectories are explained in panels D–F. (D) Bacteria swim in circles in close proximity to surfaces due to the opposite rotation of the bundle and cell body. (E) Figure eight-like patterns (i.e., change in the direction of cell rotation) are observed as cells transition between the floor (clockwise movement) and ceiling (counterclockwise movement) of channels. (F) Elongated cells swim in straight trajectories when they are positioned an equal distance between the two surfaces. Panels G–I describe the physical interpretation of these phenotypes. (G) In close proximity to a surface, the swimming bacteria are trapped in a potential well principally arising from hydrodynamic forces. (H) The presence of two surfaces introduces two equilibrium positions for bacteria and rotational diffusion enables cells to move between the floor and ceiling. (I) If the two surfaces are in close proximity, the two potential wells merge and the equilibrium position is located in the middle of the channel.

E. coli cells with length < 2 μm moved in both circular and figure eight-like trajectories in channels with a height < 3 μm (Fig. 5B). We deconstructed the motion of cells into three steps (Fig. 5E). (1) Cells moved in circular trajectories near surfaces and became trapped in a potential energy well. (2) Rotational diffusion enabled cells to cross the energy barrier (Fig. 5H) and contact the other surface where they became trapped in another potential energy well. (3) Upon contacting the other surface, cells moved in circular trajectories in which the direction of motion remained clockwise in relation to the surface. This hypothesis was confirmed by our observation that cells leaving the first surface and contacting the second surface moved out of the focal plane of the microscope (see ESI†movies). The frequency at which cells performed loops depended on the distance between the two surfaces: for 3 μm long cells, the frequency of the loops increased from 0.02 s−1 (channel height, 3 μm) to 0.15 s−1 (channel height, 1.9 μm).

When the height of the channels was < 2.5 μm and E. coli cells were > 3 μm long, the cells moved in a linear trajectory (Fig. 5C). This phenomenon has been mentioned in passing for tumbling bacterial cells.33 This phenotype can be explained by the merging of the potential energy wells for the cell at each surface to create a global energy minimum positioned half way along the z-axis of the channel (Fig. 5I). Berg and coworkers hypothesized that the characteristically low-curvature trajectories of swarmer cells in close contact to surfaces could be due to the frequent collision of cells with the surface or by cells moving in liquids surrounded by no-slip surfaces.22 Our observations are in agreement with the second hypothesis, and provide a value for the maximum height of fluid in which linear cell trajectories are possible.

From pairwise interaction to the behavior of a dense colony of motile E. coli cells

During swarming, E. coli perform four different types of maneuvers: (1) cells at the very edge of a swarm stall due to the lack of fluid surrounding them; (2) cells move in characteristically straight trajectories; (3) cells may move laterally if they collide with adjacent cells;11,12 and (4) cells reverse abruptly as the motors that actuate the flagella change direction.11 We recapitulated several of these characteristic features of swarms in the microfluidic device using elongated E. coli HCB437 cells.

As the microfluidic channels were taller than the diameter of E. coli cells and filled with motility buffer, we were unable to observe cells stall in the device; however, we recapitulated the other three characteristic features. Isolated E. coli cells moved through fluid in the device with linear trajectories. When the trajectory of a cell overlapped with another cell, the collision was inelastic and the cells frequently aligned.34 After colliding, the cells moved together through the fluid in a pair-wise interaction. We observed that the cells eventually separated from each other due principally to the difference in speed between cells (~ 80% of the interactions, n = 100) or due to rotational diffusion (~ 20% of the interactions, n = 100). Pair-wise interactions between E. coli cells can be considered a minimal cell raft. This phenotype is only possible in a two-dimensional geometry as near-field interactions in three-dimensional fluids inhibit the parallel motion of pairs of cells and produce twisted cell trajectories.35

We observed reversals in the motion of elongated E. coli HCB437 cells, however they occurred infrequently compared to reports of reversals during swarming.10 This observation was not surprising as this maneuver requires that flagella motors switch between counter-clockwise and clockwise motions, and E. coli strain HCB437 is unable to reverse the direction of its motors due to the deletion of the principal genes responsible for chemotaxis.17 Reversals only occurred in our system when cells collided forcefully with other cells, the cell body was jammed into the bundle of flagella, and the polarity of the cell was reversed.36

In a dilute suspension of cells (~ 10−3 cells per μm2), we primarily observed rafts consisting of two cells interacting through pair-wise interactions. As we increased the density of bacteria inside the channel to > 10−3 cells per μm2, we observed a progressive increase in the size of the cell rafts. At a cell density approaching the density of cells in a swarming colony (~ 5 × 10−2 cells per μm2),10 we observed the formation of large rafts of cells that traveled through the channel cohesively and in a linear trajectory (see ESI†movies). The collision of cells with the raft increased the size of the raft. Cells moving at a velocity that differed from the mean velocity of cells in the raft separated and moved away. We observed that the number of cells present in rafts in our device (~ 10) was smaller than the number of cells in rafts in a swarming colony (~ 30), presumably because of the influence of the walls: rafts of E. coli cells that collided with walls fragmented into smaller rafts.

Elongated E. coli HCB437 cells displayed behaviors that were similar to swarming E. coli cells moving across an agar surface. Yet in our system short-range hydrodynamic interactions are dampened due to the boundaries (i.e., BSA-coated PDMS surfaces).9,32 Our observations are in agreement with the hypothesis that steric interactions have a profound effect on swarming. Collisions are a determinant parameter for explaining the organization of a swarm at the periphery of the colony, and the devices described in this manuscript open the door for understanding the mechanisms that coordinate multicellular behavior in dynamic bacterial communities.

Conclusions

In summary, we designed a microfluidic device which confines E. coli cells in a quasi two-dimensional layer of motility buffer. In such environment, a colony of elongated E. coli smooth swimming cells reproduces several of the salient characteristics of the complex behavior of E. coli swarmer cells at the edge of a colony. Using a bottom-up approach, we demonstrated that the linear trajectories of swarmer cells are influenced by the interactions with each single cell and the two non-slip surfaces surrounding it (the agar–fluid and the fluid–air interfaces). This particular motion is due to the height of the layer of fluid in which cells evolve. In ‘tall’ layers of fluid, single cells exhibit circular or figure eight-like trajectories. We observed several other features of swarmer cell behavior in this device, including: cell reversals and formation and dynamics of cell rafts. We demonstrated that the formation of rafts of cells is caused by frequent inelastic collision between cells, which induce the alignment of cells. In the device, the disassembly of rafts is due to differences in speed between cells and collisions between cells and the lateral walls. We envision that this device will be useful for the identification and characterization of key parameters and mechanisms underlying the complex behavior observed during bacterial swarming.

Supplementary Material

Insight, innovation, integration.

Biological insight: this paper studies how the physical dimensions of the fluid around bacterial cells guides their individual and collective behavior. The approach presented in this paper provides an experimental system for studying the transition between individual and emergent behavior. Technological innovation: to study this area, we developed a microfluidic system in which to study the individual and collective behavior of motile bacterial cells. The system is designed to suspend cells in fluids with a user-defined height between two non-slip surfaces. This configuration mimics the physical features of swarming communities of bacteria. Benefit of integration: the integration of microfluidics, microscopy, and microbiology enables us to study the physical mechanisms that underlie the complex behavior of motile bacteria.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for input from Mike Graham and Pieter Janssen. The National Science Foundation (MCB-1120832) and the USDA (WIS01594) supported this research. The authors gratefully acknowledge use of facilities and instrumentation supported by the University of Wisconsin Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (DMR-1121288). D.B. Weibel acknowledges support from an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Fellowship.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Movies of (1) eight-like trajectory and (2) formation of cell rafts. See DOI: 10.1039/c3ib40130h

Notes and references

- 1.Berg HC. Random Walks in Biology. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg HC. E coli in Motion. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purcell EM. Am J Phys. 1977;45:3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renner LD, Weibel DB. MRS Bull. 2011;36:347. doi: 10.1557/mrs.2011.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Copeland MF, Weibel DB. Soft Matter. 2009;5:1174. doi: 10.1039/B812146J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kearns DB. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:634. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harshey RM, Matsuyama T. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones B, Young R, Mahenthiralingam E, Stickler DJ. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3941. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.3941-3950.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuson HH, Copeland MF, Carey S, Sacotte R, Weibel DB. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:368. doi: 10.1128/JB.01537-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darnton NC, Turner L, Rojevsky S, Berg HC. Biophys J. 2010;98:2082. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner L, Zhang R, Darnton NC, Berg HC. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:3259. doi: 10.1128/JB.00083-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Copeland MF, Flickinger ST, Tuson HH, Weibel DB. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:1241. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02153-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sokolov A, Aranson IS, Kessler JO, Goldstein RE. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;98:158102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.158102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu XL, Libchaber A. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;84:3017. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y, Berg HC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118238109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maki N, Gestwicki JE, Lake EM, Kiessling LL, Adler J. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4337. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4337-4342.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfe AJ, Conley MP, Berg HC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:6711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia Y, Whitesides GM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1998;37:550. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980316)37:5<550::AID-ANIE550>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/.

- 20.Fauvart M, Phillips P, Bachaspatimayum D, Verstraeten N, Fransaer J, Michiels J, Vermant J. Soft Matter. 2012;8:70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemelle L, Palierne JF, Chartre E, Place C. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:6307. doi: 10.1128/JB.00397-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang R, Turner L, Berg HC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912804107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li G, Tang JX. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;103:078101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.078101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li G, Bensson J, Nisimova L, Munger D, Mahautmr P, Tang JX, Maxey MR, Brun YV. Phys Rev E. 2011;84:041932. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.84.041932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berke AP, Turner L, Berg HC, Lauga E. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;101:038102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.038102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiLuzio WR, Turner L, Mayer M, Gartecki P, Weibel DB, Berg HC, Whitesides GM. Nature. 2005;435:1271. doi: 10.1038/nature03660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg HC, Turner L. Biophys J. 1990;58:919. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82436-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauga E, DiLuzio WR, Whiteside GM, Stone HA. Biophys J. 2006;90:400. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.069401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li G, Tam LK, Tang JX. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807305105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berg HC. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R689. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vigeant MAS, Wagner M, Tamm LK, Ford RM. Langmuir. 2001;17:2235. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drescher K, Dunkel J, Cisneros LH, Ganguly S, Goldstein RE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019079108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Binz M, Lee AP, Edwards C, Nicolau DV. Microelectron Eng. 2010;87:810. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aranson IS, Sokolov A, Kessler JO, Goldstein RE. Phys Rev E. 2007;75:040901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.040901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishikawa T, Sekiya G, Imai Y, Yamaguchi T. Biophys J. 2007;93:2217. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cisneros L, Dombrowski C, Golstein RE, Kessler JO. Phys Rev E. 2006;73:030901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.73.030901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.