Abstract

Tetrathiomolybdate (TM), a potent copper-chelating drug, was initially developed for the treatment of Wilson’s disease. Our working hypothesis is that the fibrotic pathway is copper-dependent. Because biliary excretion is the major pathway for copper elimination, a bile duct ligation (BDL) mouse model was used to test the potential protective effects of TM. TM was given in a daily dose of 0.9 mg/mouse by means of intragastric gavage 5 days before BDL. All the animals were killed 5 days after surgery. Plasma liver enzymes and total bilirubin were markedly decreased in TM-treated BDL mice. TM also inhibited the increase in plasma levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 seen in BDL mice. Cholestatic liver injury was markedly attenuated by TM treatment as shown by histology. Hepatic collagen deposition was significantly decreased, and it was paralleled by a significant suppression of hepatic smooth muscle α-actin and fibrogenic gene expression in TM-treated BDL mice. Although the endogenous antioxidant ability was enhanced, oxidative stress as shown by malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxyalkenals, hepatic glutathione/oxidized glutathione ratio, was not attenuated by TM treatment, suggesting the protective mechanism of TM may be independent of oxidative stress. In summary, TM attenuated BDL-induced cholestatic liver injury and fibrosis in mice, in part by inhibiting TNF-α and TGF-β1 secretion. The protective mechanism seems to be independent of oxidative stress. Our data provide further evidence that TM might be a potential therapy for hepatic fibrosis.

Tetrathiomolybdate (TM) was first developed as an anti-copper drug for the treatment of neurological symptoms in patients with Wilson’s disease (Brewer et al., 1991). Because of its fast action and low toxicity, TM may prove to be a useful drug for the initial treatment of Wilson’s disease. Later, it was found to have anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and immune-mediating effects.

TM was shown to have anticancer effects in both tumor models (Pan et al., 2002; Cox et al., 2003) and a phase I clinical study (Brewer et al., 2000). One mechanism for the anticancer effects is through inhibition of angiogenesis (Lowndes and Harris, 2005), with copper serving as an important cofactor for angiogenesis. Many proangiogenic cytokines, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor, IL-6, and IL-8, are copper-dependent (Pan et al., 2002). One mechanism of suppression of cytokine signaling is through inhibition of nuclear factor-κB (Pan et al., 2002). Based on its antiangiogenic property, TM was determined to be an effective treatment in retinal neovascularization (Elner et al., 2005).

Antifibrotic effects of TM were also observed in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis (Brewer et al., 2003) and carbon tetrachloride-induced cirrhosis mouse models (Askari et al., 2004). Both studies showed that TM protected against fibrosis by inhibition of TGF-β, the key cytokine in fibrogenesis.

In some other animal experiments, TM was shown to protect against liver injury induced by concanavalin A (Con A) (Askari et al., 2004) and acetaminophen (Ma et al., 2004), and heart injury induced by doxorubicin in mice (Hou et al., 2005). In these studies, levels of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β were significantly decreased by TM treatment.

TM was also shown to have protective effects in autoimmune disease animal models, including a type I diabetes model in nonobese diabetic mice (Brewer et al., 2006), an autoimmune arthritis model (Omoto et al., 2005; McCubbin et al., 2006), and a Con A autoimmune hepatitis model (Askari et al., 2004).

The mechanism of action of TM involves forming a stable tripartite complex with copper and protein that is unavailable for cellular uptake (Mills et al., 1981). Given with food, TM binds copper in food and endogenously secreted copper with protein in the alimentary tract, and it prevents copper absorption. Given away from food, TM is absorbed into the blood and complexes free copper with plasma albumin. This complex is primarily degraded in the liver, with copper excretion in the bile.

Copper is an essential trace element for many biological processes. It serves as a cofactor for a number of enzymes, such as cytochrome oxidase, copper/zinc SOD (SOD1), metal-lothionein, and several transcription factors (Linder and Hazegh-Azam, 1996). In general, copper is taken up into hepatocyte and incorporated into ceruloplasmin in the Golgi apparatus, and then it is secreted into the serum as holoceruloplasmin, a mature form of ceruloplasmin (Murata et al., 1995). Because the synthesis of ceruloplasmin is directly regulated by the bioavailability of copper to the liver, it is a good surrogate marker of body copper status. The copper in ceruloplasmin accounts for approximately 90% of the total plasma copper (Goodman et al., 2004). Because 80% of the copper leaving the liver is excreted via the bile, biliary excretion represents the major pathway of copper elimination (Luza and Speisky, 1996). Excessive copper accumulation in the liver secondary to cholestasis has been well documented in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (Deering et al., 1977). Copper levels are also elevated in a variety of other clinical and experimental liver diseases, probably due to impaired excretion (Togashi et al., 1992; Ebara et al., 2003).

The present study investigated the potential use of TM in an animal model of hepatic cholestasis. The working hypothesis is that the hepatic fibrotic pathway is modulated by copper (Brewer et al., 2004). Our objective was to test the potential protective effects of TM in a bile duct ligation (BDL) mouse model of hepatic fibrosis.

Materials and Methods

Animal Surgery and Experimental Protocol

Male C57BL/6J mice weighing 20 to 25 g were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). They were housed in the animal facilities of University of Louisville Research Resources Center on a 12-h light/ dark cycle, and they were fed food and water ad libitum for 1 week before beginning the experiments. All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, which is certified by the American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. The animals were randomly divided into four groups: five for sham operation alone, five for sham operation plus TM, 10 for BDL plus TM, and 10 for BDL alone. Tetrathiomolybdate [TM, (NH4)2MoS4, PubChem Substance ID 24859366], as an ammonium salt (kindly provided by Dr. George Brewer, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), was dissolved in deionized water. In TM-treated animals, it was given in a daily dose of 0.9 mg/mouse by means of intragastric gavage, beginning 5 days before BDL. Mice were fed a low copper diet (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) with copper content of 2 mg/kg.

Bile duct ligation was performed using a standard technique (Uchinami et al., 2006). In brief, mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine. After midline laparotomy, the common bile duct was exposed and twice ligated with 6-0 silk suture. Sham operation was performed by gently touching the bile duct. The abdomen was closed in layers, and the animals were allowed to recover on a heat pad. All the animals were killed 5 days after surgery, and blood and liver samples were harvested.

Copper Status

Ceruloplasmin was used as a surrogate marker of copper status because the liver secretes ceruloplasmin into the blood in an amount that depends on copper availability (Hou et al., 2005), and it was measured on the basis of its oxidase activity (Schosinsky et al., 1974) in blood from retro-orbital sinus bleeding.

Liver Enzyme Assay

Plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP), and total bilirubin assays were performed using commercially available kits (Infinity; Thermo Electron Corporation, Melbourne, Australia) based on a colorimetric method.

Cytokine Assay

Plasma TNF-α and TGF-β1 levels were determined using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded liver sections were cut at 3 μm in thickness using a routine procedure. Liver injury was determined by staining with Masson’s trichrome. Extracellular matrix accumulation in liver sections was determined by staining with Sirius red-fast green (López-De León and Rojkind, 1985). The area of positive Sirius red staining of liver section was quantified using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). In particular, a Molecular Devices Image-1/AT image acquisition and analysis system incorporating an Axioskop 50 microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) was used to capture and analyze eight nonoverlapping fields per section at 400× magnification. Data from each section were pooled to determined means. Image analysis was performed using techniques described previously (Bergheim et al., 2006).

For immunohistochemical analysis, sections were incubated with anti-α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) (1/1000; Dako North America, Inc., Carpenteria, CA), for 30 min. Staining was visualized using the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated Dako staining system (Dako In-Vision; Dako North America, Inc.).

Isolation of RNA and Real-Time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from liver tissues using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For real-time RT-PCR, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using TaqMan Reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The reverse transcription was carried out using 1× TaqMan RT buffer (5.5 mM MgCl2, 500 mM each dNTP, 2.5 mM random hexamer, 8 U of RNase inhibitor, and 25 U of Multiscribe reverse transcriptase with 200 ng of total RNA). The RT conditions were 10 min at 25°C, 30 min at 48°C, and 5 min at 95°C. Reactions in which the enzyme or RNA was omitted were used as negative controls. Real-time PCR was performed with an ABI Prism 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) and SYBR Green I dye reagents. Primers were designed by Primer Express Software, version 3.0 (Applied Biosystems) (Table 1). The parameter threshold cycle was defined as the fraction cycle number at which the fluorescence passed the threshold. The relative gene expression was analyzed using 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) by normalizing with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene expression in all the experiments.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for real-time RT-PCR detection of gene expression

| Gene | GenBank Accession No. | Direction | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIMP-1 | NM_011593 | Forward | CGCCTACACCCCAGTCATG |

| Reverse | TGCGGTTCTGGGACTTGTG | ||

| MMP-9 | NM_013599 | Forward | AGTGGGACCATCATAACATCACAT |

| Reverse | TCTCGCGGCAAGTCTTCAG | ||

| Procollagen I α1 | NM_007742 | Forward | CTTCACCTACAGCACCCTTGTG |

| Reverse | TGACTGTCTTGCCCCAAGTTC | ||

| PAI-1 | M33960 | Forward | TCTCCAATTACTGGGTGAGTCAGA |

| Reverse | GCAGCCGGAAATGACACAT | ||

| GAPDH | XR_004428 | Forward | CTGACATGCCACCTGGAGAA |

| Reverse | TGCCTGCGTCACCACCTT |

Western Blot

Western blot analysis was carried out in liver homogenates. Equal amounts of protein were loaded and resolved on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA). The membrane was blocked and probed with primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) for SOD1 (dilution 1:500) overnight at 4°C, and then it was incubated with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Protein signals were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Hepatic Lipid Peroxidation and GSH/GSSG Assay

Lipid peroxidation was assessed by measuring MDA and 4-HAE using commercial kits (Oxford Biomedical Research, Oxford, MI). Reduced glutathione (GSH) and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography as described previously (Richie and Lang, 1987).

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

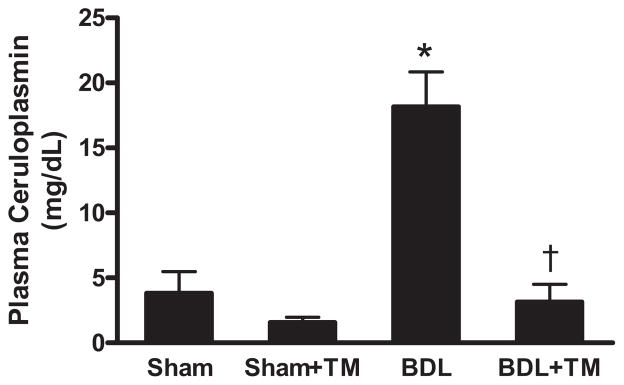

Copper Status

The plasma ceruloplasmin level was significantly elevated (approximately 5-fold) in the mice 5 days after BDL. The mean ceruloplasmin level in TM-treated BDL animals was markedly lower than that of animals with BDL alone (approximately 20% BDL) (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Plasma ceruloplasmin levels after 5-day bile duct ligation. BDL or sham surgery (Sham) was performed in male C57BL/6J mice as described under Materials and Methods. Some mice were pretreated with tetrathiomolybdate (TM) at 0.9 mg/mouse/day by intragastric gavage 5 days before BDL until 5 days after BDL (BDL + TM), and some mice received the same amount of tetrathiomolybdate from the day of sham surgery (sham + TM). Ceruloplasmin levels were determined in plasma samples. Data represent means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *, significantly different from sham group; †, significantly different from BDL group.

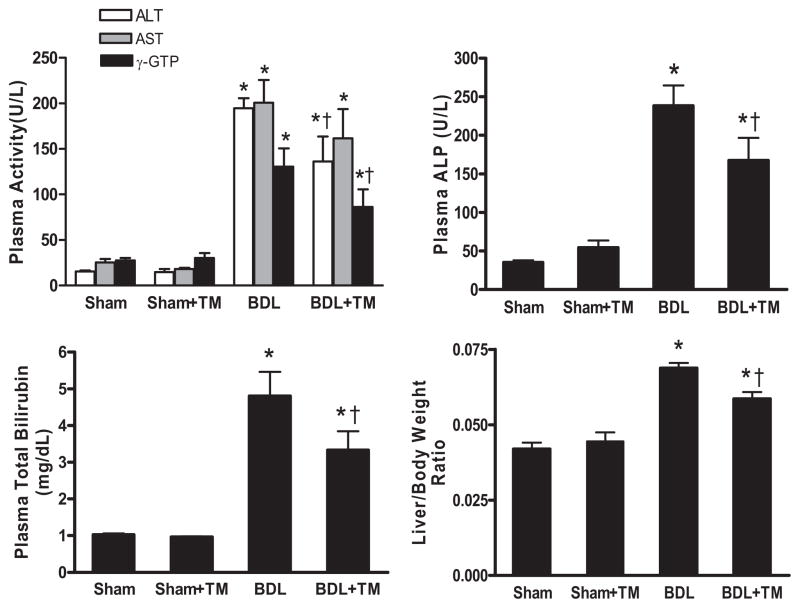

TM Attenuated Cholestatic Liver Injury Induced by BDL

Liver injury was assessed by plasma levels of liver enzymes (ALT, AST, γ-GTP, and ALP), total bilirubin, liver/ body weight ratio, and histology. As expected, after 5 days, BDL significantly increased plasma levels of these enzymes and total bilirubin compared with sham-operated animals (Fig. 2). These parameters were within normal ranges in both sham-operation and sham-operation plus TM-treated mice. The increase in plasma ALT, γ-GTP, ALP, and total bilirubin caused by BDL was significantly reduced by 30 to 34% in TM-treated BDL mice. Liver/body weight ratio in TM-treated BDL mice was also significantly lower than that of BDL mice, suggesting that tissue remodeling was more effective in TM-treated mice compared with untreated BDL mice (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of TM on plasma liver enzymes, total bilirubin, and liver/body weight ratio on sham-operated and BDL mice. The animals were subjected to the same treatment protocol as described in Fig. 1. ALT, AST, γ-GTP, ALP, and total bilirubin were determined in plasma samples by colorimetric assay. Data represent means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *, significantly different from sham group; †, significantly different from BDL group.

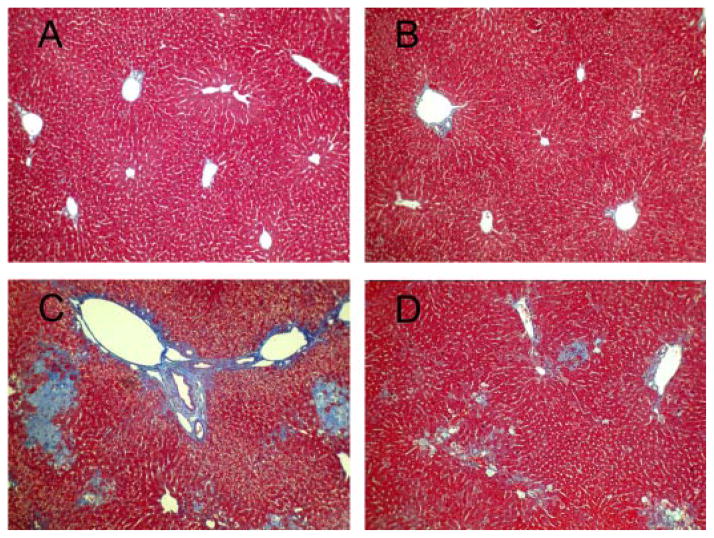

Masson’s trichrome staining showed extensive bile infarcts, which are confluent foci of hepatocyte feathery degeneration due to bile acid cytotoxicity, bile duct proliferation, and bridging fibrosis in untreated BDL mice (Fig. 3C). All these lesions were markedly attenuated in TM-treated BDL mice (Fig. 3D). No pathological changes were observed in liver tissues from mice with sham operation and sham operation plus TM (Fig. 3, A and B).

Fig. 3.

BDL-induced histopathological changes in the livers 5 days after surgery. Representative photomicrographs of liver sections processed for Masson’s trichrome staining: sham (A), sham + TM (B), BDL (C), and BDL + TM (D). Extensive bile infarcts, bile duct proliferation, and bridging fibrosis in untreated BDL mice is shown in C. All these lesions were markedly attenuated in TM-treated BDL mice (D). No pathological changes were observed in liver tissues with sham operation and sham + TM (A and B). Original magnification, 100×.

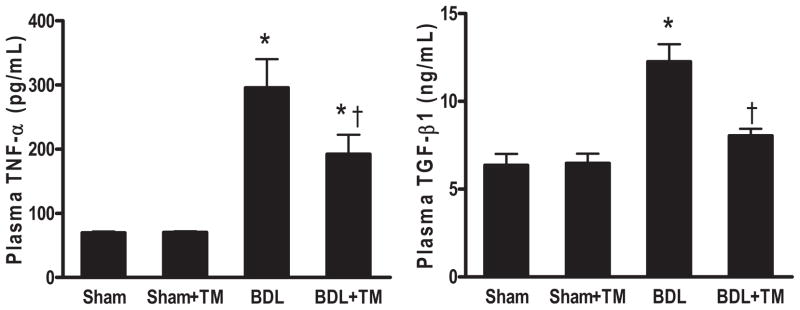

TM Attenuated Increased Plasma TNF-α and TGF-β1 Levels Induced by BDL

Plasma inflammatory and fibrogenic cytokines, TNF-α and TGF-β1, which play important roles in the activation of hepatic stellate cells, were significantly increased by 4- and 2-fold after 5 days BDL (Fig. 4). However, both TNF-α and TGF-β1 production were significantly blunted in TM-treated BDL mice compared with untreated BDL mice. TNF-α was decreased by 35% in TM-treated BDL mice. TGF-β1 production was almost completely blocked compared with control level, suggesting that TM may protect against cholestatic liver injury and fibrogenesis by inhibiting increases in inflammatory and fibrogenic cytokines.

Fig. 4.

Plasma TNF-α and TGF-β1 levels after 5 days BDL or sham surgery. Plasma TNF-α and TGF-β1 levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. There is no significant difference between sham and sham + TM group in both TNF-α and TGF-β1 levels. Plasma TGF-β1 in BDL + TM group is significantly decreased compared with BDL group. There is no significant difference among BDL + TM, sham, and sham +TM group. Data represent means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *, significantly different from sham group; †, significantly different from BDL group.

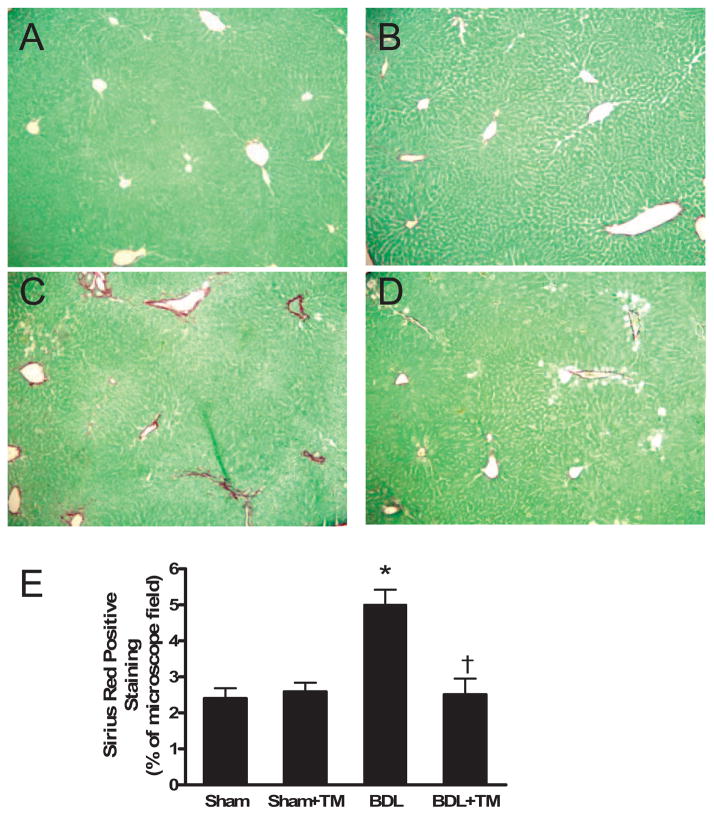

TM Attenuated Hepatic Fibrosis Induced by BDL

Collagen content was assessed by morphometrical analysis of Sirius red staining of liver sections. Five days after BDL, the accumulation of collagen was discernible in the liver sections stained with Sirius red. In sham-operated mouse livers, only normal staining around vessels was observed (Fig. 5, A and B), whereas mild bridging fibrosis was seen in livers from BDL mice (Fig. 5C), which was markedly reduced in TM-treated BDL mouse livers (Fig. 5D). Quantification of Sirius red staining by image analysis showed that collagen content was significantly increased by 2-fold in the livers of BDL mice compared with sham and sham plus TM-treated mice, and it was significantly decreased with TM treatment in BDL mouse livers (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

Hepatic collagen accumulation after 5 days BDL. Representative photomicrographs of liver sections processed for Sirius red staining: sham (A), sham + TM (B), BDL (C), and BDL + TM (D). In sham-operated and sham-operated plus TM mouse livers (A and B), only normal staining around vessels was observed, whereas mild bridging fibrosis was seen in livers from BDL mice (C), and it was markedly reduced in TM-treated BDL mouse livers (D). Original magnification, 100×. Quantification of Sirius red-positive staining showed that collagen content in BDL + TM group is significantly decreased compared with BDL group (E). There is no significant difference among BDL + TM, sham, and sham + TM group. Data represent means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *, significantly different from sham group; †, significantly different from BDL group.

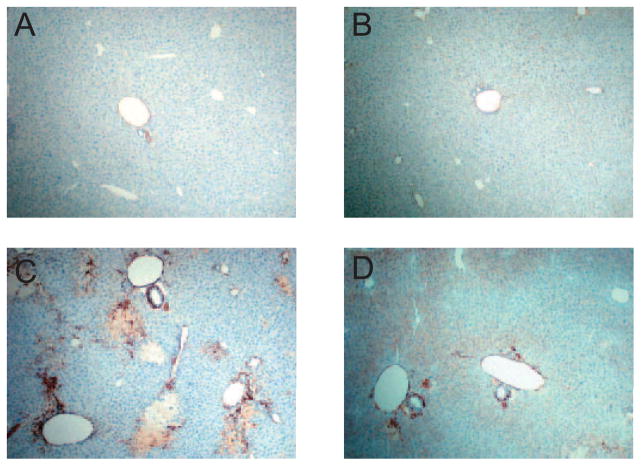

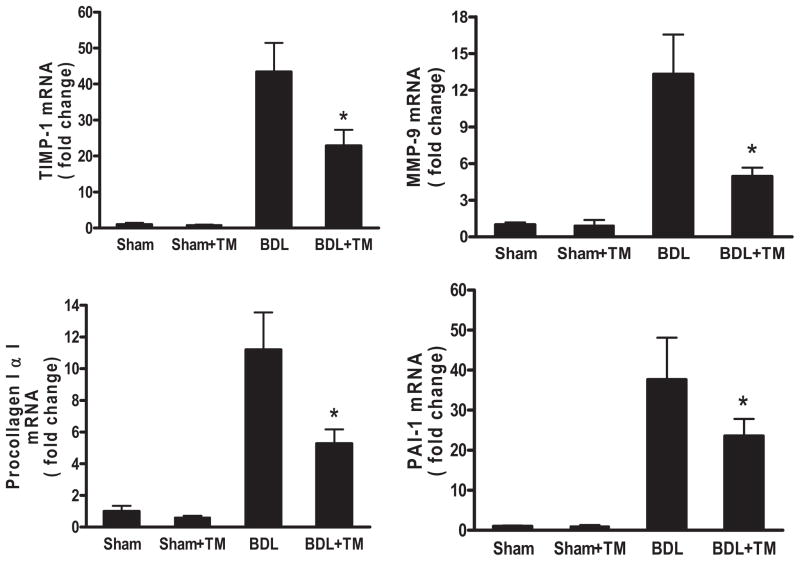

Immunohistochemical staining for α-SMA, a marker of hepatic stellate cell activation, showed that its expression was significantly increased in the livers of mice with BDL (Fig. 6, C and D) compared with that in sham-operated mice (Fig. 6, A and B). However, it was markedly diminished in the livers of TM-treated BDL mice (Fig. 6D) compared with BDL mice (Fig. 6C). We further evaluated the gene expression implicated in fibrogenesis (Fig. 7). Real-time RT-PCR data showed that the mRNA expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease (TIMP)-1, which inhibits collagen degradation by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and protects hepatic stellate cells from apoptosis (Yoshiji et al., 2002), was significantly up-regulated 40-fold in the livers of BDL mice, and it was decreased to 43% in TM-treated BDL mice. MMP-9, one of the members of MMP family, also called gelatinase B, is known to regulate cell matrix composition by degrading components of the extracellular matrix (Roderfeld et al., 2006). The level of MMP-9 mRNA expression was significantly up-regulated 13-fold in the livers of BDL mice, and it was decreased to 37% in TM-treated BDL mice. Pro-collagen I α1 mRNA expression, which encodes the major collagen type in fibrosis, increased approximately 11-fold in the livers of BDL mice compared with sham-operated mice, and this increase was reduced by 46% in TM-treated BDL mice, which was paralleled by a significant attenuation of liver collagen content, as assessed by Sirius red staining. Plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1), a key regulator of fibrinolysis by plasmin (Bergheim et al., 2006), showed a 40-fold mRNA level increase in BDL mouse livers, which decreased to 62% with TM treatment.

Fig. 6.

Hepatic α-SMA expression after 5 days BDL. Representative photomicrographs of immunohistochemistry staining for liver α-SMA. A, sham. B, sham + TM. C, BDL. D, BDL + TM. α-SMA expression was significantly increased in the liver of mice with BDL (C) compared with that in sham-operated mice (A and B), and it was markedly diminished in the liver of BDL mice treated with TM (D). Original magnification, 100×.

Fig. 7.

Hepatic fibrogenic gene expression after 5 days BDL. Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described under Materials and Methods to determine hepatic TIMP-1, MMP-9, procollagen I α1, and PAI-1 mRNA expression. The expression was normalized as a ratio using GAPDH as housekeeping gene. A value of 1 for this ratio was arbitrarily assigned to the data obtained from sham-operated mice. Data represent means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *, significantly different from BDL group.

TM Protects against Cholestatic Hepatic Injury and Fibrosis Induced by BDL May Be Independent of Oxidative Stress

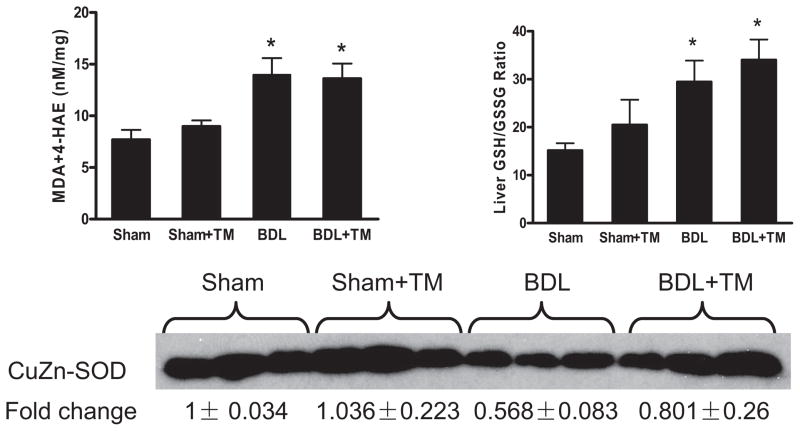

To evaluate the possible effects of TM on the state of oxidative stress, measurements of lipid peroxidation products, GSH/GSSG ratio, and SOD1 were carried out in liver homogenates. MDA and 4-HAE are the end products of lipid peroxidation, and they can serve as markers of lipid peroxidation (Esterbauer et al., 1991). As shown in Fig. 8, MDA and 4-HAE increased approximately 2-fold in the livers of BDL mice compared with sham-operated mice. However, TM pretreatment did not prevent the increase of hepatic MDA and 4-HAE. GSH/GSSG ratio, which is an indicator of oxidative stress (Barón and Muriel, 1999), significantly increased in BDL mice compared with those with sham operation, and there was no significant change with TM treatment. SOD1, one of the three eukaryotic SOD enzymes, which plays an important role in the antioxidant defense system in the liver by eliminating superoxide anion radicals (Zelko et al., 2002), was significantly decreased in BDL mouse livers compared with sham-operated mice, which have abundant expression as shown by Western blot analysis (Fig. 8, bottom). This decrease in BDL mouse livers was abolished by TM treatment. Despite enhanced endogenous antioxidant capacity in terms of SOD1, oxidative stress as assessed by lipid peroxidation and GSH/GSSG ratio was not affected by TM treatment in BDL mice. These data suggest that TM protection against hepatic injury and fibrosis induced by BDL may be independent of oxidative stress.

Fig. 8.

Oxidative Stress after 5 days BDL. Lipid peroxidation was assessed by MDA + 4-HAE in liver homogenate. Liver GSH/GSSG ratio was determined by HPLC. SOD1 expression was examined by Western blot analysis using whole liver extract, and optical density of band was quantified by ImageJ software. A value of 1 was arbitrarily assigned to the data obtained from sham-operated mice. MDA + 4-HAE and liver GSH/GSSG ratio are significantly increased in both BDL and BDL + TM group compared with sham and sham + TM group. There is no significant difference between BDL and BDL + TM group. Data represent means ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *, significantly different from sham group.

Discussion

TM was first introduced as an anticopper drug for the initial treatment of patients with Wilson’s disease. Later, it was found to be effective in murine models of carbon tetra-chloride-induced liver fibrosis and bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. At this time, there is no ideal drug therapy for hepatic fibrosis. We postulated that copper may be important in the development/evolution of hepatic fibrosis. Our objective was to test the potential protective effects of TM in BDL mouse model. We showed that TM effectively protected against liver injury as assessed by histologic examination (Fig. 3), and that it attenuated fibrosis as evaluated by Sirius red staining (Fig. 5), α-SMA (Fig. 6), and fibrogenic gene expression, such as TIMP-1, MMP-9, procollagen I α1, and PAI-1 (Fig. 7). The increase in the plasma inflammatory cytokine and fibrogenic cytokine, TNF-α and TGF-β1, was markedly blocked by TM pretreatment in BDL mice, suggesting that TM can exert both anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects (Fig. 4). This is consistent with previous reports in other models (Askari et al., 2004; Brewer et al., 2004). Because TM seems to have both anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects, it was important to study TM in a system such as the BDL model, which induces rapid hepatic fibrosis with only a modest inflammatory response. TM previously has been shown to be protective in models of liver injury that involve acute inflammation/necrosis/apoptosis such as that caused by acetaminophen, Con A, and carbon tetrachloride (Askari et al., 2004; Ma et al., 2004). If the major therapeutic target for TM is hepatic fibrosis, then evaluating a model such as BDL that causes reproducible fibrosis was critical.

It currently seems that a goal of TM therapy is to maintain ceruloplasmin at midrange, which is between 20 and 70% of baseline. Reducing copper to this level can inhibit some copper-containing angiogenic promoters, such as VEGF and fibroblast growth factor, which require higher levels of copper to be active, and yet they meet the basic cellular needs for copper (Brewer et al., 2003). In this study, the copper level in BDL mice treated with TM was maintained at approximately 30% of that normal mouse with standard diet (10 –11 mg/dl ceruloplasmin; unpublished data). Maintaining ceruloplasmin at this level was effective at attenuating liver injury and fibrosis induced by BDL. In sham-operated mice treated with TM, copper level dropped to approximately 15% of baseline, and weight loss was observed compared with sham-operated mice without TM therapy. However, there was no further weight loss in BDL mice treated with TM compared with untreated BDL mice.

Evidence of oxidative stress has been reported in cholestatic liver disease such as in primary biliary cirrhosis patients (Kawamura et al., 2000) and in BDL animal models (Barón et al., 1999; Uchinami et al., 2006), and it is often associated with decreased antioxidant defenses. We observed enhanced lipid peroxidation 5 days after BDL (Fig. 8). GSH/ GSSG ratio, an indicator of antioxidant defenses, was significantly increased in BDL mouse livers (Fig. 8). This increase may be a compensatory response to enhanced lipid oxidation. TM treatment did not influence this glutathione response. However, SOD1, one of the oxygen radical scavenging enzymes in liver, which is copper-related, was markedly suppressed after BDL, and it was partially rescued by anticopper treatment (Fig. 8, bottom). Collectively, despite some improvement in antioxidant defenses, enhanced lipid peroxidation was not attenuated by TM treatment, suggesting the protective mechanism involving anticopper therapy for BDL mice may be independent of oxidative stress. It is interesting to note that although lipid peroxidation can be attenuated by antioxidants such as vitamin E and N-acetylcysteine, liver injury or fibrosis generally is not prevented (Barón et al., 1999; Tahan et al., 2007). A recent study by Zhong et al. (2002) showed that gene delivery of mitochondrial-SOD (SOD2) blocked formation of oxygen radicals and TNF-α and TGF-β synthesis, thereby attenuating liver injury caused by cholestasis. However, those effects cannot be attained by gene delivery of cytosolic SOD1, suggesting mitochondrial oxidative stress may be playing a role in cholestasis-induced liver injury and fibrosis.

The mechanism(s) of anticopper therapy for fibrosis remain to be elucidated. It is already known that the fibrogenic cytokines, connective tissue growth factor, and TGF-β are copper-dependent (Brewer et al., 2006). However, how copper regulates the fibrotic pathway is still unknown. It has been reported that hypoxia-induced activation of hepatic stellate cells occurs through the TGF-β signaling pathway, and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α gene expression was significantly up-regulated in cultured stellate cells in response to hypoxia (Shi et al., 2007). HIF-1 is a ubiquitously expressed transcriptional master regulator of many genes involved in mammalian oxygen homeostasis. It was originally identified as a regulatory factor for the erythropoietin gene. Other target genes of HIF-1 are involved in iron metabolism, angiogenesis, control of blood flow, glucose uptake, and glycolysis. HIF-1 also is a metal-responsive transcription factor, and it may play an important role in metal-induced carcinogenesis. HIF-1 is an α1β1 heterodimer with the α subunit the regulatory component, which is unique to the hypoxic response (Martin et al., 2005). In cultured human cardiomyocytes, copper-stimulated VEGF expression and angiogenesis is mediated via activating HIF-1α (Jiang et al., 2007). Copper also has been shown to modulate HIF-1 transcriptional activity in hepatoma cells by stabilizing nuclear HIF-1α under normoxic condition (Martin et al., 2005). In the present study, copper/ceruloplasmin levels and plasma TGF-β1 were markedly increased after BDL. Whether high copper can induce HIF-1α expression and whether HIF-1α induces TGF-β expression and activation of hepatic stellate cells in cholestatic liver diseases require further investigation.

In summary, our data provide evidence that TM is effective at attenuating BDL-induced cholestatic liver injury and fibrosis, in part by reducing TNF-α and TGF-β1. The protection may be independent of oxidative stress. The molecular mechanism(s) involving copper modulation of fibrotic pathways is an important area for future investigation, and it represents a potential therapeutic target for hepatic fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant AA015970 (to C.J.M.). G.J.B. is the recipient of research support from Pipex Therapeutics, Inc. The University of Michigan has recently licensed the antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory uses of TM to Pipex Therapeutics, Inc. (Ann Arbor, MI). G.J.B. has equity in and is a paid consultant to Pipex Therapeutics, Inc.

We thank Sheron C. Lear and co-workers for technical support on histology.

ABBREVIATIONS

- TM

tetrathiomolybdate

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- IL

interleukin

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- Con A

concanavalin A

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- BDL

bile duct ligation

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- γ-GTP

γ-glutamyl transpeptidase

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- 4-HAE

hydroxyalkenal

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

- α-SMA

smooth muscle α-actin

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease

- MMP

matrix metalloprotease

- PAI

plasminogen activator inhibitor

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

Footnotes

This manuscript was presented as a poster presentation as follows: Song M, Deaciuc IV, Song Z, Barve S, Zhang J, Lin M, Chen T, Arteel GE, Brewer G, and McClain CJ (2007) Tetrathiomolybdate protects against hepatic fibrosis induced by bile duct ligation in mice. Digestive Disease Week; 2007 May 19 –24; Washington, DC. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), Alexandria, VA.

References

- Askari FK, Dick R, Mao M, Brewer GJ. Tetrathiomolybdate therapy protects against concanavalin A and carbon tetrachloride hepatic damage in mice. Exp Biol Med. 2004;229:857– 863. doi: 10.1177/153537020422900820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barón V, Muriel P. Role of glutathione, lipid peroxidation and antioxidants on acute bile-duct obstruction in the rat. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1472:173–180. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergheim I, Guo L, Davis MA, Duveau I, Arteel GE. Critical role of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in cholestatic liver injury and fibrosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:592– 600. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.095042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Dick RD, Grover DK, LeClaire V, Tseng M, Wicha M, Pienta K, Redman BG, Jahan T, Sondak VK, et al. Treatment of metastatic cancer with tetrathiomolybdate, an anticopper, antiangiogenic agent: phase I study. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Dick R, Ullenbruch MR, Jin H, Phan SH. Inhibition of key cytokines by tetrathiomolybdate in the bleomycin model of pulmonary fibrosis. J Inorg Biochem. 2004;98:2160–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Dick RD, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkin V, Tankanow R, Young AB, Kluin KJ. Initial therapy of patients with Wilson’s disease with tetrathiomolybdate. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:42– 47. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530130050019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Dick R, Zeng C, Hou G. The use of tetrathiomolybdate in treating fibrotic, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases, including the non-obese diabetic mouse model. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:927–930. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Ullenbruch MR, Dick R, Olivarez L, Phan SH. Tetrathiomolybdate therapy protects against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. J Lab Clin Med. 2003;141:210–216. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2003.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C, Merajver SD, Yoo S, Dick RD, Brewer GJ, Lee JS, Teknos TN. Inhibition of the growth of squamous cell carcinoma by tetrathiomolybdate-induced copper suppression in a murine model. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:781–785. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.7.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deering TB, Dickson ER, Fleming CR, Geall MG, McCall JT, Baggenstoss AH. Effect of D-penicillamine on copper retention in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:1208–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebara M, Fukuda H, Hatano R, Yoshikawa M, Sugiura N, Saisho H, Kondo F, Yukawa M. Metal contents in the liver of patients with chronic liver disease caused by hepatitis C virus. Reference to hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2003;65:323–330. doi: 10.1159/000074645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elner SG, Elner VM, Yoshida A, Dick RD, Brewer GJ. Effects of tetra-thiomolybdate in a mouse model of retinal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:299–303. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman VL, Brewer GJ, Merajver SD. Copper deficiency as an anti-cancer strategy. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:255–263. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0110255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou G, Dick R, Abrams GD, Brewer GJ. Tetrathiomolybdate protects against cardiac damage by doxorubicin in mice. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;146:299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Reynolds C, Xiao C, Feng W, Zhou Z, Rodriguez W, Tyagi SC, Eaton JW, Saari JT, Kang YJ. Dietary copper supplementation reverses hypertrophic cardiomyopathy induced by chronic pressure overload in mice. J Exp Med. 2007;204:657– 666. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura K, Kobayashi Y, Kageyama F, Kawasaki T, Nagasawa M, Toyokuni S, Uchida K, Nakamura H. Enhanced hepatic lipid peroxidation in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3596–3601. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder MC, Hazegh-Azam M. Copper biochemistry and molecular biology. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:797S– 811S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods. 2001;25:402– 408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-De León A, Rojkind M. A simple micromethod for collagen and total protein determination in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 1985;33:737–743. doi: 10.1177/33.8.2410480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowndes SA, Harris AL. The role of copper in tumour angiogenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2005;10:299–310. doi: 10.1007/s10911-006-9003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luza SC, Speisky HC. Liver copper storage and transport during development: implications for cytotoxicity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:812S– 820S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.5.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Hou G, Dick RD, Brewer GJ. Tetrathiomolybdate protects against liver injury from acetaminophen in mice. J Appl Res Clin Exp Ther. 2004;4:419– 426. [Google Scholar]

- Martin F, Linden T, Katschinski DM, Oehme F, Flamme I, Mukhopadhyay CK, Eckhardt K, Troger J, Barth S, Camenisch G, et al. Copper-dependent activation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1: implications for ceruloplasmin regulation. Blood. 2005;105:4613– 4619. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin MD, Hou G, Abrams GD, Dick R, Zhang Z, Brewer GJ. Tetrathiomolybdate is effective in a mouse model of arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2501–2506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills CF, El-Gallad TT, Bremner I, Weham G. Copper and molybdenum absorption by rats given ammonium tetrathiomolybdate. J Inorg Biochem. 1981;14:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)80037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Yamakawa E, Iizuka T, Kodama H, Abe T, Seki Y, Kodama M. Failure of copper incorporation into ceruloplasmin in the Golgi apparatus of LEC rat hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;209:349–355. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoto A, Kawahito Y, Prudovsky I, Tubouchi Y, Kimura M, Ishino H, Wada M, Yoshida M, Kohno M, Yoshimura R, et al. Copper chelation with tetrathiomolybdate suppresses adjuvant-induced arthritis and inflammation-associated cachexia in rats. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R1174–R1182. doi: 10.1186/ar1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Q, Kleer CG, van Golen KL, Irani J, Bottema KM, Bias C, De Carvalho M, Mesri EA, Robins DM, Dick RD, et al. Copper deficiency induced by tetrathiomolybdate suppresses tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4854– 4859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie JP, Jr, Lang CA. The determination of glutathione, cyst(e)ine, and other thiols and disulfides in biological samples using high-performance liquid chromatography with dual electrochemical detection. Anal Biochem. 1987;163:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roderfeld M, Weiskirchen R, Wagner S, Berres ML, Henkel C, Grotzinger J, Gressner AM, Matern S, Roeb E. Inhibition of hepatic fibrogenesis by matrix metalloproteinase-9 mutants in mice. FASEB J. 2006;20:444– 454. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4828com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schosinsky KH, Lehmann HP, Beeler MF. Measurement of ceruloplasmin from its oxidase activity in serum by use of o-dianisidine dihydrochloride. Clin Chem. 1974;20:1556–1563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YF, Fong CC, Zhang Q, Cheung PY, Tzang CH, Wu RS, Yang M. Hypoxia induces the activation of human hepatic stellate cells LX-2 through TGF-beta signaling pathway. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahan G, Tarcin O, Tahan V, Eren F, Gedik N, Sahan E, Biberoglu N, Guzel S, Bozbas A, Tozun N, et al. The effects of N-acetylcysteine on bile duct ligation-induced liver fibrosis in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3348–3354. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9717-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togashi Y, Li Y, Kang JH, Takeichi N, Fujioka Y, Nagashima K, Kobayashi H. D-Penicillamine prevents the development of hepatitis in Long-Evans Cinnamon rats with abnormal copper metabolism. Hepatology. 1992;15:82– 87. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchinami H, Seki E, Brenner DA, D’Armiento J. Loss of MMP 13 attenuates murine hepatic injury and fibrosis during cholestasis. Hepatology. 2006;44:420–429. doi: 10.1002/hep.21268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Yoshii J, Ikenaka Y, Noguchi R, Nakatani T, Tsujinoue H, Yanase K, Namisaki T, Imazu H, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 attenuates spontaneous liver fibrosis resolution in the transgenic mouse. Hepatology. 2002;36:850– 860. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.35625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelko IN, Mariani TJ, Folz RJ. Superoxide dismutase multigene family: a comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:337–349. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00905-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z, Froh M, Wheeler MD, Smutney O, Lehmann TG, Thurman RG. Viral gene delivery of superoxide dismutase attenuates experimental cholestasis-induced liver fibrosis in the rat. Gene Ther. 2002;9:183–191. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]