Abstract

Background

The world faces the challenge to develop sustainable technologies to replace thousands of products that have been generated from fossil fuels. Microbial cell factories serve as promising alternatives for the production of diverse commodity chemicals and biofuels from renewable resources. For example, polylactic acid (PLA) with its biodegradable properties is a sustainable, environmentally friendly alternative to polyethylene. At present, PLA microbial production is mainly dependent on food crops such as corn and sugarcane. Moreover, optically pure isomers of lactic acid are required for the production of PLA, where D-lactic acid controls the thermochemical and physical properties of PLA. Henceforth, production of D-lactic acid through a more sustainable source (CO2) is desirable.

Results

We have performed metabolic engineering on Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 for the phototrophic synthesis of optically pure D-lactic acid from CO2. Synthesis of optically pure D-lactic acid was achieved by utilizing a recently discovered enzyme (i.e., a mutated glycerol dehydrogenase, GlyDH*). Significant improvements in D-lactic acid synthesis were achieved through codon optimization and by balancing the cofactor (NADH) availability through the heterologous expression of a soluble transhydrogenase. We have also discovered that addition of acetate to the cultures improved lactic acid production. More interestingly, 13C-pathway analysis revealed that acetate was not used for the synthesis of lactic acid, but was mainly used for synthesis of certain biomass building blocks (such as leucine and glutamate). Finally, the optimal strain was able to accumulate 1.14 g/L (photoautotrophic condition) and 2.17 g/L (phototrophic condition with acetate) of D-lactate in 24 days.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated the photoautotrophic production of D-lactic acid by engineering a cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803. The engineered strain shows an excellent D-lactic acid productivity from CO2. In the late growth phase, the lactate production rate by the engineered strain reached a maximum of ~0.19 g D-lactate/L/day (in the presence of acetate). This study serves as a good complement to the recent metabolic engineering work done on Synechocystis 6803 for L-lactate production. Thereby, our study may facilitate future developments in the use of cyanobacterial cell factories for the commercial production of high quality PLA.

Background

Fossil fuels helped literally ignite the industrial revolution, and from then on radically changed the way we live; today, thousands of products are generated from fossil fuels [1]. Unfortunately, fossil fuels are non-renewable and their reserves will foreseeably run dry. Moreover, the reckless use of this resource has resulted in a tremendous release of greenhouse gases leading to adverse effects to our earth’s climate and to the creatures living on our planet. These drawbacks have driven researchers to look for alternative renewable replacements for petroleum and petroleum-derived products. Amongst the petroleum-derived products; polyethylene with an annual productivity of 80 million metric tons per annum stands out as one of the most commonly used plastics [2]. Polylactic acid (PLA) is made by the polymerization of lactic acid and has the potential to replace polyethylene as a biodegradable alternative [3]. Lactic acid is a chiral compound and exists in two isomeric forms: D (-) lactic acid and L (+) lactic acid. The various properties of polylactic acid are modulated by the mixing ratio of the D (-) and L (+) lactic acid and, henceforth, it is essential to produce both the isomers [4]. It has been estimated that for the PLA production to be profitable, the lactic acid price should be less than 0.8$/kg [5]. This necessitates the production of lactic acid from a cheaper source. Although microbial fermentation can produce lactate from sugar-based feedstock, such process may compete with global food supplies. Therefore, this work focuses on cyanobacterial process development for the sustainable synthesis of D (-) lactic acid, with CO2 as the carbon substrate and sunlight as an energy source.

Cyanobacteria have the ability to reduce atmospheric CO2 into useful organic compounds by using solar energy and have been engineered to synthesize a number of value-added products [6-9]. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (hereafter Synechocystis 6803) with its ability to uptake foreign DNA naturally, has been the model organism of choice for various metabolic engineering works [10-12]. Synechocystis 6803 also has the ability to grow mixotrophically with glucose and acetate [13]. Therefore, along with CO2, its versatile carbon metabolism allows the co-utilization of cheap organic compounds for product biosynthesis. For example, acetate abundant wastewater generated from biomass hydrolysis and anaerobic digestion [14] can be potentially used for promoting cyanobacterial productivity. More importantly, there are numerous molecular biology tools for Synechocystis 6803, making it an attractive organism for metabolic engineering works [15,16].

Synechocystis 6803 has recently been engineered for the production of L-lactate (a maximal titer of 1.8 g/L and a maximal productivity of 0.15 g/L/day) [17-19]. However, engineering Synechocystis 6803 for the production of optically pure D-lactate synthesis is more difficult due to the lack of an efficient D-lactate dehydrogenase. Recently, a mutated glycerol dehydrogenase (GlyDH*) was discovered by Wang et al. [20] and this enzyme was found to behave as a D-lactate dehydrogenase, exhibiting an unusually high specific activity of 6.9 units per mg protein with pyruvate and NADH as substrates. This enzyme allows a Bacillus coagulans strain to produce 90 g/L of D-lactate. Their work served as a motivation for us to engineer Synechocystis 6803 through the heterologous expression of gldA101 (encodes GlyDH*). We found that this original enzyme was able to synthesize optically pure D-lactate in Synechocystis 6803. To further improve cyanobacterial productivity, we employed three strategies: 1. Codon optimization of gldA101 (Additional file 1: Figure S1); 2. Heterologous expression of a transhydrogenase; 3. Supplementing cultures with extracellular carbon sources (such as glucose, pyruvate and acetate). The final engineered strain demonstrated a high D-lactic acid productivity and titer (titer >1 g/L).

Results and discussion

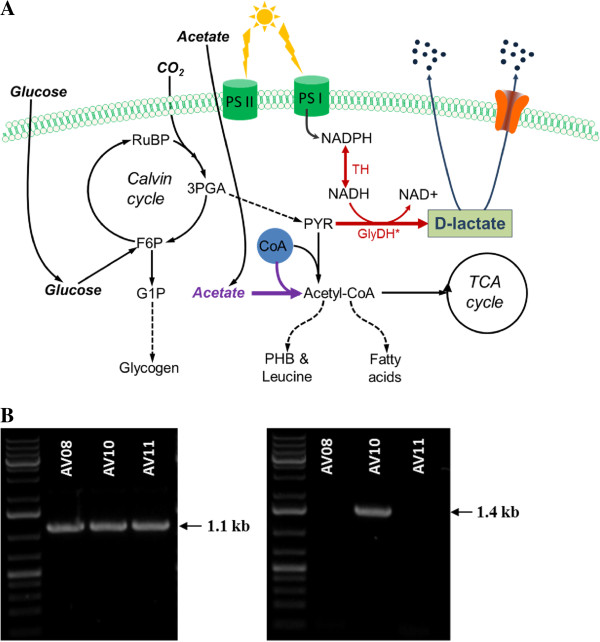

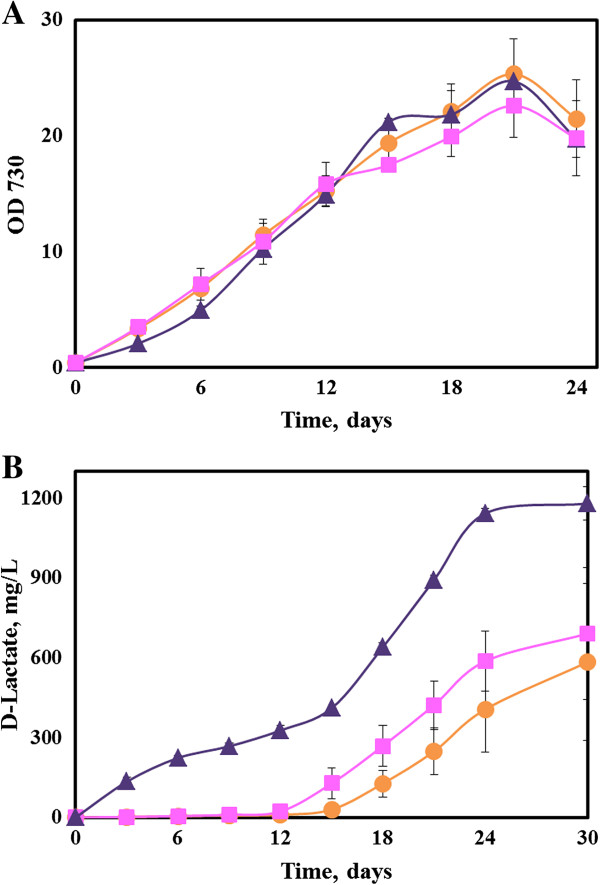

Cyanobacteria need a lactate dehydrogenase to synthesize lactate from pyruvate (Figure 1). Earlier works on Synechocystis 6803 for lactate production involved the expression of an ldh from Bacillus subtilis for synthesis of L-lactate [18]. As a first step, we tested the activity of GlyDH* for D-lactate production [20] by transferring the gene from Bacillus coagulans to Synechocystis 6803. A plasmid pYY1 was constructed that contained the gene gldA101 under the control of an Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) inducible promoter, Ptrc. The gldA101 gene was then subsequently transferred to the glucose tolerant wild type Synechocystis 6803 through natural transformation, generating the strain AV08. The optical density and the D-lactate concentration of the AV08 cultures were monitored in shake flasks. As can be verified from Figure 2, AV08 did not show any significant levels of D-lactate in the initial 12 days. The D-lactate levels started increasing steadily at the late autotrophic growth phase and reached a final titer of 0.4 g/L, whereas a wild type strain of Synechococcus 7002 was able to produce only ~ 7 mg/L of D-lactate through glucose fermentation [21].

Figure 1.

Metabolic engineering of Synechocystis 6803 for the synthesis of D-lactic acid. (A) Metabolic pathway for D-lactate synthesis. Lactate permeation through the cell membrane occurs either via a lactate transporter or by passive diffusion [22,23]. Red arrows indicate the heterologous pathway engineered into Synechocystis 6803. Abbreviations: GlyDH*, mutant glycerol dehydrogenase; TH, Transhydrogenase; 3PGA, 3-phosphoglycerate; CoA, Coenzyme A; G1P, glucose 1-phosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; PHB, poly-β-hydroxybutyrate; RuBP, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate. (B) Colony PCR to verify the presence of the heterologous genes of the mutant glycerol dehydrogenase (Left picture) and transhydrogenase (Right picture) in the engineered strains of Synechocystis 6803. gldA101 was amplified with primers gldA-o-F3 and gldA-o-R; gldA101-syn was amplified with primers gldA-o-F and gldA-o-R2; sth was amplified with primers tranNADH-F and tranNADH-R (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Autotrophic production of D-Lactate in the engineered strains of Synechocystis 6803. (A) Growth curves and (B) D-lactate production in the engineered strains (n = 3). Circles: AV08 (with gldA101). Triangles: AV10 (with gldA101-syn and sth) and Squares: AV11 (with gldA101-syn).

A familiar strategy to increase the synthesis of a target product would be to increase the levels of the heterologous enzyme inside the cell. This can be achieved by modifying the enzyme regulation either at the transcriptional level or at the translational level. Cyanobacteria are known to have their own preference in the use of codons for synthesizing amino acids [24]. Lindberg et al. [25] have employed codon optimization for the isoprene synthase gene IspS and have found a 10-fold increase in the IspS expression level. More recently, this strategy was applied to increase the expression of the efe gene (from Pseudomonas syringae) in Synechocystis 6803 for ethylene production [26]. Since the gene involved in this work was borrowed from a gram-positive organism and Synechocystis 6803 being gram-negative, we hypothesized that this would be a useful strategy. The codon optimized gene gldA101-syn (synthesized by Genewiz Inc, South Plainfield, NJ) was integrated into the psbA1 gene loci in the genome of the WT Synechocystis 6803 using the plasmid pDY3 to obtain the strain AV11.

Further improvements in product synthesis can be achieved by rectification of bottlenecks in the metabolic pathway. The lactate dehydrogenase enzyme utilizes NADH as its cofactor, whereas the ratio of NADH to NADPH is reported to be much lower in cyanobacteria. For example, the ratio of NADH to NADPH in Synechococcus 7942 under light conditions was estimated to be 0.15, and in Synechocystis 6803 under photoautotrophic conditions the intracellular NADH concentration was only 20 nmol/g fresh weight, whereas the intracellular NADPH concentration was about 140 nmol/g fresh weight [27-29]. This lower concentration of NADH in cyanobacteria, points to the fact that availability of NADH could be a major limiting factor for synthesizing D-lactate. Henceforth, a soluble transhydrogenase, sth from Pseudomonas aeruginosa[30], was introduced downstream of the gene gldA101-syn. This engineered strain was called AV10. The heterologous genes in AV10 and AV11 are under the control of the same single promoter, Ptrc, located upstream of gldA101-syn and sth in AV10 and located upstream of gldA101-syn in AV11.

The three strains (AV08, AV10 and AV11) showed similar growth rates to wild type strain under photoautotrophic conditions, and thus the production of D-lactate did not introduce growth defects in the engineered strains (Figure 2A and Additional file 1: Figure S2). However, the three strains differed in the production rate of D-lactic acid. The strain AV11 with codon optimization (gldA101-syn) had an improved productivity for D-lactate compared to the AV08 strain (Figure 2B). Both strains produced D-lactate mainly during the later growth stage. Introduction of the transhydrogenase improved the D-lactate synthesis further in AV10, and this strain produced D-lactate in both the growth phase and non-growth phase. The rate of photoautotrophic D-lactate production by AV10 increased significantly (achieving a maximum productivity of ~0.1 g/L/day and ~0.2 mmol/g cell/day) during the late phase of the culture and the final titer of D-lactate reached 1.14 g/L.

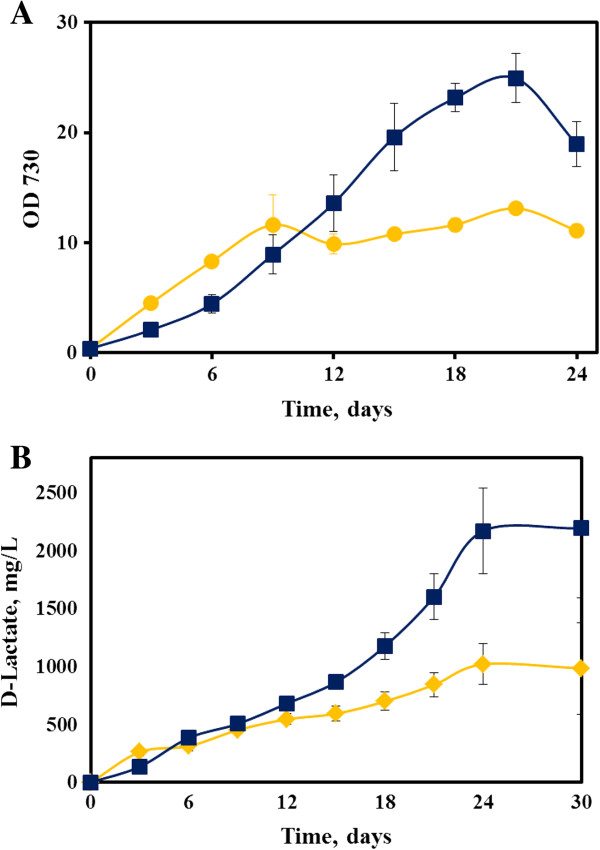

We observed that the D-lactate production rate reached its peak in the later stages of cultivation, suggesting that more carbon flux has been directed to lactate production during the non-growth phase. This increased flux was expected because the lactate precursor (pyruvate) is a key metabolic node occupying a central position in the synthesis of diverse biomass components, and more pyruvate becomes available for lactate synthesis when biomass growth becomes slow. Therefore, an obvious thought would be to enhance lactate production by supplementing the cultures with pyruvate [31]. However, our experiments found that addition of pyruvate did not yield apparent improvements in D-lactate synthesis (data not shown), possibly because Synechocystis 6803 may lack an effective pyruvate transporter. The alternate option would be to grow AV10 with glucose and increase the glycolysis flux for pyruvate synthesis. In our previous study, addition of glucose was found to increase isobutanol production in Synechocystis 6803 [32]. However in this study, when we grew the AV10 strain under mixotrophic conditions (with 5 g/L glucose), it did not show a higher growth rate or display improvements in the final D-lactate titer compared to the autotrophic condition. The AV10 cultures grown in the presence of glucose instead showed an impaired growth, possibly because the engineered pathways caused a metabolic imbalance during glucose catabolism (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mixotrophic production of D-Lactate by AV10. (A) Growth and (B) D-lactate production in the engineered Synechocystis 6803 strain AV10 (n = 3), with the provision of additional organic carbon source, i.e., with glucose and acetate (Mixotrophic metabolism). Squares: with acetate. Circles: with glucose.

We also hypothesized that the intracellular pyruvate pool can be increased for lactate production by addition of exogenous acetate. Supplementing cultures with acetate can redirect more carbon from pyruvate to lactate in three possible ways [33]: (1) acetate is used as a building block for lactate production; (2) acetate provides additional carbon source for biomass synthesis and reduce pyruvate consumption; (3) acetate conversion by acetyl-CoA synthetase consumes Coenzyme-A (CoA), decreasing the CoA pool available for pyruvate decarboxylation. To test this hypothesis, the AV10 cultures were supplemented with 15 mM acetate. We found that growth rate of the AV10 cultures with acetate (Figure 3A) remained comparable to their growth rate under autotrophic condition, but there was substantial improvement in the synthesis of D-lactate (the maximal titer reached 2.17 g/L and the peak productivity reached ~0.19 g/L/day, Figure 3B).

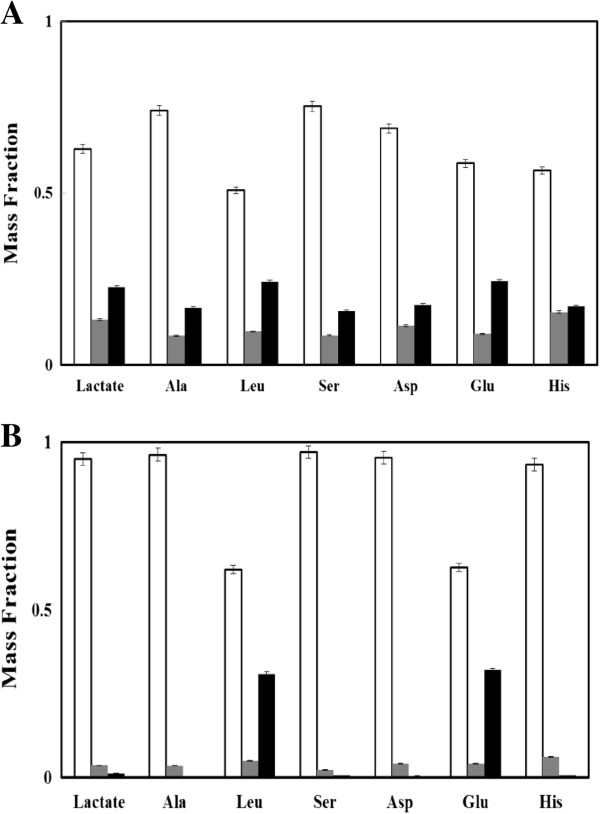

To further understand the role played by glucose and acetate in D-lactate synthesis, AV10 cultures were grown with [1,2-13C] glucose and [1,2-13C] acetate (Sigma, St. Louis). Cultures were collected from the mid-log phase and were used for amino acid and D-lactate analysis. As an example, mass spectrum of D-lactate from a cyanobacterial culture is shown in Additional file 1: Figure S3. The 13C abundance in the amino acids and lactate were obtained as mass fraction mi, where 'i’ indicates the number of 13C in the molecule. As can be seen from Figure 4A, glucose-fed cells have significant 13C-carbon distributed in amino acids (indicated by an increase in m1 and m2). Also, D-lactate from glucose-fed cultures was partially 13C-labeled (m2 ~0.22). The isotopomer data in Figure 4A proved that 13C-glucose provided the carbon source for both biomass and lactate production. However, glucose-based mixotrophic fermentation is not beneficial to D-lactate production compared to autotrophic cultures, possibly because carbon flux from glycolysis may cause some carbon and energy imbalance [32]. As for the acetate-fed cultures, only leucine and glutamate (which both use acetyl-CoA as their precursor) were significantly labeled (an m2 of 0.31 and 0.32 respectively), while other amino acids (e.g., aspartate and alanine) were nonlabeled (Figure 4B). Interestingly, D-lactate from acetate-fed culture was almost nonlabeled, indicating that the carbons of lactate molecules were mainly derived from CO2. Therefore, the observed enhancement of lactate synthesis in the presence of acetate can be explained by two complementary mechanisms. First, acetate is an additional carbon source for synthesizing biomass building blocks, such as fatty acids and some amino acids, thus redirecting the extra carbon flux from CO2 to lactate. Secondly, acetate may limit the pyruvate decarboxylation reaction by reducing the CoA pool by the formation of acetyl-CoA and thus improve pyruvate availability for lactate synthesis.

Figure 4.

Isotopomer analysis showing the mass fraction of isotopomers for selected proteinogenic amino acids [TBDMS based measurement] and D-lactate [MSTFA based measurement]. Standard abbreviations are used for amino acids in the figure. (A) Cultures grown with 5 g/L of [1,2-13C] glucose and (B) Cultures grown with 15 mM of [1,2-13C] acetate. "white bar" m0 – mass fraction without any labeled carbon; "grey bar" m1 – mass fraction with one labeled carbon; "black bar" m2 – mass fraction with two labeled carbon. (Note: natural 13C makes up about 1.1% of total carbon as measurement background).

Conclusions

The results reported here are for the autotrophic production of D-lactate in cyanobacteria via the heterologous expression of a novel D-lactate dehydrogenase (GlyDH*) and by balancing the precursors and cofactors. Other molecular strategies may also be applied to further improve the D-lactate production: (1) by seeking stronger promoters [16]; (2) optimizing ribosomal binding sites [34]; (3) improving activity of GlyDH* via protein engineering; (4) introducing powerful lactate transporter [22]; (5) knocking out competing pathways (such as the glycogen and polyhydroxybutyrate synthesizing pathways); (6) duplicating the heterologous genes by integrating at multiple sites [35]; and (7) limiting biomass production by knocking down the pyruvate decarboxylation reaction. Also, considering the future outdoor algal processes for scaled up D-lactate production, we hypothesize that knocking out metabolic pathways that synthesize carbon storage molecules (polyhydroxybutyrate and glycogen) may be deleterious to algal growth during the night phase in day-night cultivation [36]. On the other hand, process optimization by employing better light conditions, along with proper CO2 concentration, pH and temperature control, may also be employed to increase the D-lactate productivity in a scaled-up system.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Restriction enzymes, Phusion DNA polymerase, T4 DNA ligase and 10-Beta electro-competent E. coli kit were purchased from Fermentas or New England BioLabs. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). All organic solvents, chemicals, 13C-labeled acetate, and glucose used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Medium and growth conditions

E. coli strain 10-Beta was used as the host for all plasmids constructed in this study. E. coli cells were grown in liquid Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C in a shaker at 200 rpm or on solidified LB plates. Ampicillin (100 μg/mL) or kanamycin (50 μg/mL) was added to the LB medium when required for propagation of the plasmids in E. coli. The wild-type (glucose-tolerant) and the recombinant strain of Synechocystis 6803 were grown at 30°C in a liquid blue-green medium (BG-11 medium) or on solid BG-11 plates at a light intensity of 100 μmol of photons m-2 s-1 in ambient air. Kanamycin (20 μg/mL) was added to the BG-11 growth medium as required. Growth of the cells was monitored by measuring their optical density at 730 nm (OD730) with an Agilent Cary 60 UV–vis spectrophotometer. 10 mL cultures for the synthesis of D-lactate were grown (initial OD730, 0.4) in 50-mL shake flasks without any antibiotic and 1 mM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added for induction. Mixotrophic cultures of Synechocystis 6803 were started in BG-11 medium containing a known amount of glucose (0.5%) or acetate (15 mM) as an organic carbon source.

Plasmid construction and transformation

The vector pTKA3 [32] served as the backbone for all the plasmids constructed in this study. The gene gldA101 encoding GlyDH* [20], was amplified from the plasmid pQZ115 with the primers gldA-o-F2 and gldA-o-R (Tables 1 and 2). The obtained 1.2 kb fragment was digested with BamHI/NheI and cloned into the same restriction sites of pTKA3, yielding the vector pYY1. A gene cassette, which consists of the codon optimized gldA101 (i.e., gldA101-syn) with the promoter Ptrc in the upstream and the transhydrogenase (sth) gene from Pseudomonas aeruginosa[30] in the downstream, was chemically synthesized by Genewiz Inc (South Plainfield, NJ) and cloned into the commonly used E. coli vector pUC57-kan resulting in the plasmid vector pUC57-glda_sth. The vector pUC57-glda_sth was digested with BamHI/NheI, and the yielding 2.6 kb fragment was cloned into the corresponding restriction sites of pTKA3, resulting in the vector pDY2. The vector pDY3 was constructed by self-ligation of the 8.2 kb fragment obtained through the digestion of pDY2 with KpnI.

Table 1.

Primer sequences

| Primer name | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|

| gldA-o-F |

GGATCCTTGACAATTAATCATCCGGCTCG |

| gldA-o-F2 |

GGATCCTTGACAATTAATCATCCGGCTCGTATAATGTGTGGAATTGTGAGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGGAGATATAATCATATGACGAAAATCATTACCTCTCCAAGCAAGTTTATACAAGG |

| gldA-o-F3 |

ATGACGAAAATCATTACCTCTCCAAG |

| gldA-o-R |

GCTAGCTCATGCCCATTTTTCCTTATAATACCGCCCG |

| gldA-o-R2 |

TTAGGCCCACTTTTCCTTGTAATAGC |

| tranNADH-F |

CCTAAGCTAGCGGAGGACTAGCATGG |

| tranNADH-R |

GCTAGCGGTACCTCAAAAAAGCCGG |

| ptka3-F |

CCCGAAGTGGCGAGCCCGAT |

| CO-F |

TTGATGTTGCCTTTGAACCC |

| O-F |

ATGGATACGAAAGTGATTGC |

| sth-F |

GAGCTACCACCTGCGCAACA |

| AMV17R |

GCGCGACTCCCCGTCTTTGACTATCCTTTTTAGGATGGGGCA |

| ps1_up_fwda | TACCGGAACAGGACCAAGCCTT |

Table 2.

Plasmids and strains

|

Plasmids/Strains |

Description |

Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC57-glda_sth |

Chemically synthesized gene cassette consisting of Ptrc, gldA101-syn and sth. |

Genewiz;

[20,30,37] |

| pQZ115 |

Plasmid carrying gldA101 |

[20] |

| pTKA3 |

Backbone plasmid for all vectors constructed in this study, with psbA1 as the integration loci. |

[32] |

| pYY1 |

Derived from pTKA3 with gldA101 and the promoter, Ptrc. |

This study |

| pDY2 |

Derived from pTKA3 with gldA101-syn, sth and the promoter, Ptrc. |

This study |

| pDY3 |

Derived from pTKA3 with gldA101-syn and the promoter, Ptrc. |

This study |

|

Strains | ||

|

E. coli 10-Beta |

Cloning host strain. |

New England Biolabs |

|

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 |

Glucose tolerant wild type, naturally competent. |

This study |

| AV08 |

Synechocystis Ptrc::gldA101::Kmr, GlyDH* of Bacillus. |

This study |

| AV10 |

Synechocystis Ptrc::(gldA101-syn)-sth::Kmr, GlyDH* of Bacillus, transhydrogenase of Pseudomonas. |

This study |

| AV11 | Synechocystis Ptrc::gldA101-syn::Kmr, GlyDH* of Bacillus. | This study |

Natural transformation of Synechocystis 6803 was performed by using a double homologous-recombination procedure as described previously [38]. Recombinant colonies appeared between 7 and 10 days post inoculation. The genes of interest were finally integrated into the psbA1 gene loci (a known neutral site under normal growth conditions) in the genome of Synechocystis 6803 [32]. For segregation, the positive colonies were propagated continuously onto BG-11 plates containing kanamycin and segregation of colonies was verified through a colony PCR with the primers AMV17R and ps1_up_fwda (Table 1). The promoter and the heterologous genes in the engineered strains were PCR amplified with respective primers (ptka3-F, CO-F, O-F, sth-F) (Table 1) and sent for sequencing to Genewiz to verify the cloning accuracy.

D (-) lactate analysis

D(-)/L(+) lactic acid detection kit (R-biopharm) was used to measure the D-lactate concentration. Samples of the cyanobacterial culture (50 μL) were collected every 3 days and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and the D-lactate concentration assay was performed following the manufacturer’s instruction. All the reactions were performed in a 96-well plate reader at room temperature (Infinite 200 PRO microplate photometer, TECAN).

13C isotopomer experiment

To estimate the carbon contributions of glucose and acetate for biomass and D-lactic acid synthesis a 13C labeling experiment was performed. The mutant AV10 was grown in a BG-11 medium with 0.5% glucose (1,2-13C2 glucose) or 15 mM acetate (U-13C2 acetate) (Sigma, St. Louis). Cultures were started at an OD730 of 0.4 and were grown with labeled glucose or acetate for over 48 hours. The biomass samples and supernatant were collected for measurement of lactate and amino acid labeling.

The proteinogenic amino acids from biomass were hydrolyzed and then derivatized with TBDMS [N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-N-methyl-trifluoroacetamide], as described previously [39]. The derivatized amino acids were analyzed for their 13C mass fraction by GC-MS (Hewlett Packard 7890A and 5975C, Agilent Technologies, USA) equipped with a DB5-MS column (J&W Scientific) [39]. The fragment [M-57]+ containing information of the entire amino acid was used for calculating the 13C mass fractions (M: the molecular mass of the derivatized amino acids). The fragment [M-15]+ was used only for leucine, since its [M-57]+ overlaps with other mass peak [40]. To analyze extracellular D-lactic acid labeling, the supernatant (0.2 mL) was first freeze-dried at -50°C. The dried samples were then pre-derivatized with 200 μL of 2% methoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine for 60 minutes at 37°C and then derivatized with 300 μL N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl) trifluroacetamide (TMS) for 30 minutes at room temperature. The natural abundance of isotopes, including 13C (1.13%), 18O (0.20%), 29Si (4.70%) and 30Si (3.09%) changes the mass isotopomer spectrum. These changes were corrected using a published algorithm and the detailed measurement protocol can be found in our previous paper [41].

Competing interests

The authors declare competing financial interests since this work is being covered by a pending patent application from Washington University in St. Louis.

Authors' contributions

AMV conceived the initial idea for this research. AMV, YY, and YJT designed the experiments. AMV, YY, and YL performed the experiments. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Nuleotide sequence alignment of gldA101 and the codon-optimized gldA101 (i.e., gldA101-syn, synthesized by Genewiz Inc). Conserved nucleotide sequences in gldA101-syn are indicated as dotted lines. Figure S2. Autotrophic growth curve for Synechocystis 6803 strains shows similar growth of the engineered D-lactate producing strains as compared to the wild type strain. Diamond: Wild type. Square: AV08. Triangle: AV10. Circle: AV11. Figure S3. Mass spectra obtained via GC-MS confirm the presence of lactate in the cell culture supernatant of AV10 strain. D/L lactate enzyme kit (R-Biopharm) was used to further confirm that the product is an optically pure D-lactate.

Contributor Information

Arul M Varman, Email: avarman@go.wustl.edu.

Yi Yu, Email: yu_yi@whu.edu.cn.

Le You, Email: leyou@go.wustl.edu.

Yinjie J Tang, Email: yinjie.tang@seas.wustl.edu.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor K. T. Shanmugam for offering us the plasmid pQZ115. We thank Professor Himadri Pakrasi at WUSTL for his advice on this project. We also thank Dianyi Liu, Kanimozhi, and Zach Hembree for their help with experiments, and Sandra Matteucci from the WUSTL Engineering Communication Center, for her close reading of the manuscript. This research was funded by an NSF Career Grant (MCB0954016).

References

- Frost JW, Draths KM, Knop DR, Harrup MK, Barker JL, Niu W. Carbon management: implications for R & D in the chemical sciences and technology (a workshop report to the chemical sciences roundtable) Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2001. Chemicals from plants. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piringer OG, Baner AL. Plastic packaging: interactions with food and pharmaceuticals. 2. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar J, Aravindan R, Viruthagiri T. Recent trends in the production, purification and application of lactic acid. Chem Biochem Eng Q. 2008;22:245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Garlotta D. A literature review of poly (lactic acid) J Polym Environ. 2001;9:63–84. doi: 10.1023/A:1020200822435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taskila S, Ojamo H. In: Lactic acid bacteria - R & D for food, health and livestock purposes. Kongo M, editor. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech; 2013. The current status and future expectations in industrial production of lactic acid by lactic acid bacteria. [Google Scholar]

- Atsumi S, Higashide W, Liao JC. Direct photosynthetic recycling of carbon dioxide to isobutyraldehyde. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:1177–1180. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan EI, Liao JC. Metabolic engineering of cyanobacteria for 1-butanol production from carbon dioxide. Metab Eng. 2011;13:353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Pugh S, Nielsen DR, Zhang W, Meldrum DR. Engineering cyanobacteria for photosynthetic production of 3-hydroxybutyrate directly from CO2. Metab Eng. 2013;16:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusakabe T, Tatsuke T, Tsuruno K, Hirokawa Y, Atsumi S, Liao JC, Hanai T. Engineering a synthetic pathway in cyanobacteria for isopropanol production directly from carbon dioxide and light. Metab Eng. 2013;20C:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Wang J, Zhang W, Meldrum DR. Application of synthetic biology in cyanobacteria and algae. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:344. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, You L, Liu D, Hollinshead W, Tang Y, Zhang F. Development of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 as a Phototrophic Cell Factory. Mar Drugs. 2013;11:2894–2916. doi: 10.3390/md11082894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berla BM, Saha R, Immethun CM, Maranas CD, Moon TS, Pakrasi HB. Synthetic biology of cyanobacteria: unique challenges and opportunities. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:246. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu GF, Shen ZY, Wu QY. Modification of carbon partitioning to enhance PHB production in Synechocystis sp PCC6803. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2002;30:710–715. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(02)00044-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Ruan ZH, Liu ZG, Wu SG, Varman AM, Liu Y, Tang YJJ. Engineering Escherichia coli to convert acetic acid to free fatty acids. Biochem Eng J. 2013;76:60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Huang H-H, Camsund D, Lindblad P, Heidorn T. Design and characterization of molecular tools for a synthetic biology approach towards developing cyanobacterial biotechnology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2577–2593. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HH, Lindblad P. Wide-dynamic-range promoters engineered for cyanobacteria. J Biol Eng. 2013;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph A, Aikawa S, Sasaki K, Tsuge Y, Matsuda F, Tanaka T, Kondo A. Utilization of lactic acid bacterial genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 in the production of lactic acid. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77:966–970. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermayr SA, Paszota M, Hellingwerf KJ. Engineering a cyanobacterial cell factory for production of lactic acid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7098–7106. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01587-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermayr SA, Hellingwerf KJ. On the use of metabolic control analysis in the optimization of cyanobacterial biosolar cell factories. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:11169–11175. doi: 10.1021/jp4013152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Ingram LO, Shanmugam KT. Evolution of D-lactate dehydrogenase activity from glycerol dehydrogenase and its utility for D-lactate production from lignocellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:18920–18925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111085108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely K, Xu Y, Bennette N, Bryant DA, Dismukes GC. Redirecting reductant flux into hydrogen production via metabolic engineering of fermentative carbon metabolism in a cyanobacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:5032–5038. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00862-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederholtmeyer H, Wolfstadter BT, Savage DF, Silver PA, Way JC. Engineering cyanobacteria to synthesize and export hydrophilic products. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:3462–3466. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00202-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axe DD, Bailey JE. Transport of lactate and acetate through the energized cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1995;47:8–19. doi: 10.1002/bit.260470103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WH, Gowri G. Codon usage in higher-plants, green-algae, and cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol. 1990;92:1–11. doi: 10.1104/pp.92.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg P, Park S, Melis A. Engineering a platform for photosynthetic isoprene production in cyanobacteria, using Synechocystis as the model organism. Metab Eng. 2010;12:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerer J, Tao L, Davis M, Ghirardi M, Maness P-C, Yu J. Sustained photosynthetic conversion of CO2 to ethylene in recombinant cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5:8998–9006. doi: 10.1039/c2ee22555g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vermaas WFJ. Photosynthesis and respiration in cyanobacteria. In eLS: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tamoi M, Miyazaki T, Fukamizo T, Shigeoka S. The Calvin cycle in cyanobacteria is regulated by CP12 via the NAD(H)/NADP(H) ratio under light/dark conditions. Plant J. 2005;42:504–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Uchimiya H, Hihara Y. Difference in metabolite levels between photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic cultures of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 examined by capillary electrophoresis electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:3009–3018. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wermuth B, Kaplan NO. Pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: purification by affinity chromatography and physicochemical properties. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1976;176:136–143. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker TM, Zhang S, Laborde SM, Mayer PR, Frankel LK, Moroney JV. The malic enzyme is required for optimal photoautotrophic growth of Synechocystis sp. Strain PCC 6803 under continuous light but Not under a diurnal light regimen. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:8144–8148. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.8144-8148.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varman AM, Xiao Y, Pakrasi HB, Tang YJ. Metabolic engineering of Synechocystis sp. Strain PCC 6803 for isobutanol production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;79:908–914. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02827-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendisch VF, de Graaf AA, Sahm H, Eikmanns BJ. Quantitative determination of metabolic fluxes during coutilization of two carbon sources: comparative analyses with Corynebacterium glutamicum during growth on acetate and/or glucose. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3088–3096. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.11.3088-3096.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidorn T, Camsund D, Huang HH, Lindberg P, Oliveira P, Stensjo K, Lindblad P. Synthetic biology in cyanobacteria engineering and analyzing novel functions. Methods Enzymol. 2011;497:539–579. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385075-1.00024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Zhao H, Li Z, Tan X, Lu X. Photosynthetic production of ethanol from carbon dioxide in genetically engineered cyanobacteria. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5:9857–9865. doi: 10.1039/c2ee22675h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gründel M, Scheunemann R, Lockau W, Zilliges Y. Impaired glycogen synthesis causes metabolic overflow reactions and affects stress responses in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Microbiology. 2012;158:3032–3043. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.062950-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosius J, Erfle M, Storella J. Spacing of the -10 and -35 regions in the tac promoter. Effect on its in vivo activity. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3539–3541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang XN, Liu B, Liu SM, Arunakumara K, Zhang XC. Optimum conditions for transformation of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Microbiol. 2007;45:241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You L, Page L, Feng X, Berla B, Pakrasi HB, Tang YJ. Metabolic pathway confirmation and discovery through 13C-labeling of proteinogenic amino acids. J Vis Exp. 2012;59:e3583. doi: 10.3791/3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G. Accurate assessment of amino acid mass isotopomer distributions for metabolic flux analysis. Anal Chem. 2007;79:7554–7559. doi: 10.1021/ac0708893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Shui W, Myers S, Feng X, Bertozzi C, Keasling J. Central metabolism in Mycobacterium smegmatis during the transition from O2-rich to O2-poor conditions as studied by isotopomer-assisted metabolite analysis. Biotechnol Lett. 2009;31:1233–1240. doi: 10.1007/s10529-009-9991-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Nuleotide sequence alignment of gldA101 and the codon-optimized gldA101 (i.e., gldA101-syn, synthesized by Genewiz Inc). Conserved nucleotide sequences in gldA101-syn are indicated as dotted lines. Figure S2. Autotrophic growth curve for Synechocystis 6803 strains shows similar growth of the engineered D-lactate producing strains as compared to the wild type strain. Diamond: Wild type. Square: AV08. Triangle: AV10. Circle: AV11. Figure S3. Mass spectra obtained via GC-MS confirm the presence of lactate in the cell culture supernatant of AV10 strain. D/L lactate enzyme kit (R-Biopharm) was used to further confirm that the product is an optically pure D-lactate.