Abstract

Objective(s)

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the relationship of a history of falls (a geriatric syndrome) to postoperative outcomes in older adults undergoing major elective operations.

Design

Prospective, cohort study.

Setting

Referral medical center.

Patients

Persons 65 years and older undergoing elective colorectal and cardiac operations were enrolled. The predictor variable was having fallen in the six months prior to the operation.

Interventions

None.

Main Outcome Measures

Postoperative outcomes measured included thirty-day complications, need for discharge institutionalization and thirty-day readmission.

Results

There were 235 subjects with a mean age of 74±6 years. Pre-operative falls occurred in 33%. One or more postoperative complications occurred more frequently in the group with prior falls compared to the non-fallers following both colorectal (59% vs. 25%; p=0.004) and cardiac (39% vs. 15%; p=0.002) operations. These findings were independent of advancing chronologic age. Need for discharge to an institutional care facility occurred more frequently in the group that had fallen in comparison to the non-fallers in both the colorectal (52% vs. 6%; p<0.001) and cardiac (62% vs. 32%; p=0.001) groups. Similarly, 30-day readmission was higher in the group with prior falls following both colorectal (p=0.043) and cardiac (p=0.016) operations.

Conclusions

A history of one or more falls in the six months prior to an operation forecasts increased postoperative complications, need for discharge institutionalization and thirty-day readmission across surgical specialties. Utilizing a history of prior falls in preoperative risk assessment for an older adult represents a shift from current preoperative assessment strategies.

Introduction

More than one third of all inpatient operations in the United States are performed on patients 65 years and older,1 a proportion which will increase over the next several decades.2 Existing preoperative risk assessment strategies are not adequate to meet the needs of the aging population. Current tactics either quantify risk of a single organ system (e.g., the American Heart Association cardiovascular risk assessment3) instead of the whole patient, or they sum chronic disease burden (e.g., cumulative illness rating scale4) as the measure of risk rather than quantifying global reduced physiologic reserve of the older adult termed frailty.

Falling represents one of the five core geriatric syndromes which reflect reduced physiologic reserve unique to the older adult.5–6 A geriatric syndrome is a “multifactorial health condition that occur[s] when the accumulated impairments in multiple systems render [older] persons vulnerable to situational challenges”.5 In short, geriatric syndromes are clinical symptoms which represent the frail older adult.6 In community dwelling older adults, the presence of a geriatric syndrome is closely linked to the development of functional dependence.5 While there is some data evaluating the relationship of these symptoms to outcomes in surgical7–8 and medical9 hospitalized older adults, no literature directly addresses the relationship of a history of prior falls to postoperative outcomes.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the relationship of a history of falls to surgical outcomes in older adults undergoing major elective colorectal and cardiac operations. The specific aims were to compare outcomes of patients with and without a fall within the six months prior to their operation including: thirty-day morbidity, need for discharge to an institutional care facility and thirty-day readmission.

Methods

This prospective cohort study was performed at the Denver Veteran Affairs Medical Center. Regulatory approval was obtained through the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB 08-1071). Participants were enrolled between January 2005 and October 2010. Inclusion criteria were patients 65 years and older undergoing an elective colorectal or cardiac operation. Exclusion criteria for both groups were emergent (defined as an operation within 12 hours of admission) and urgent (defined as an operation between 12 and 72 hours following admission) operations. Additional exclusion criterion for the colorectal group was the performance of an additional procedure in combination with the segmental colectomy (e.g., liver resection, exenteration).

A fall was defined as unintentionally coming to rest on the ground, floor or other lower level.10 Patients were considered to have had a fall if they had a history of one or more falls in the six-months preceding surgery. A history of falls was recorded preoperatively. In addition to the fall history, other routine pre- and intra-operative variables were recorded.

Postoperative complications were defined using the following Veterans Affairs Surgery Quality Improvement Program (VASQIP) definitions that were recorded prospectively by the research team: cardiac (cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CDARREST] or myocardial infarction [CDMI]); respiratory (pneumonia [OUPNEUMO], pulmonary embolism [PULEMBOL] or reintubation for respiratory/cardiac failure [REINTUB]); renal insufficiency [RENAINSF]; neurologic (cerebral vascular accident/stroke [CNSCVA] or coma >24 hours [CNSCOMA]); postoperative infection (deep wound surgical site infection[WNDINFD], superficial surgical site infection [SUPINFEC] or urinary tract infection[URNINFEC]); sepsis [OTHSYSEP]; deep vein thrombosis [OTHDVT] and reoperation (Return to OR [RETURNOR]). Institutionalization was defined as discharge to an institutional care facility (e.g., not home). If a patient resided in an institutional care facility preoperatively, they were not considered newly institutionalized postoperatively.

Statistical analysis was performed using bivariate comparisons for the presence or absence of a fall within six-months of the operation (the independent variable). Pre-, intra- and post-operative variables were analyzed using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. Logistic regression was performed with the dependent variable of the occurrence of one or more complication and both prior falls and age as predictor variables in order to determine if falls were related to the occurrence of one or more complications independent of advancing age. The variable age was tested separately as a continuous variable and a categorical variable (65–69 years, 70–74 years, 75–79 years and 80+ years) in bivariable and multivariable logistic regression models for both the colorectal and cardiac groups to look at age as a single predictor and to adjust for age in the relationship of having fallen in relation to the occurrence of a postoperative complication. The non-parametric Spearman correlation test was used to determine how the number of falls related to the number of complications. Finally, the ability of a fall history to forecast one or more postoperative complications was compared to established variables used to predict risk (the Charlson score, the ASA score and chronologic age). To accomplish this comparison, a multivariable logistic regression was used in which the dependent variable was the occurrence of one or more complications and the independent variables were fall history, dichotomized Charlson and ASA scores for which 3 or greater indicated the high risk category and age (used as a continuous variable). Separate analyses were performed for the colorectal and cardiac groups.

Results

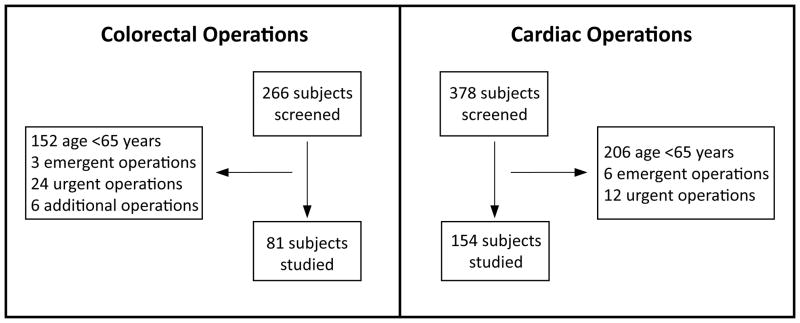

A total of 235 patients were included in the study (81 colorectal and 154 cardiac). (See Figure 1) Mean age was 74±6 years and 98% (231/235) were male. One or more falls occurred in 33% (78/235) of patients in the six months prior to the operation. One or more complications occurred in 28% (65/235). Postoperative inpatient mortality occurred in 2% (5). Baseline characteristics of fallers and non-fallers were compared. Among patients undergoing colorectal operations, baseline characteristics different in the faller’s group were: older age, higher ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) class, lower albumin, higher creatinine, lower hematocrit and higher Charlson score. (see Table 1) Among patients undergoing cardiac operations, baseline characteristics different in the faller’s group were: older age, lower albumin, lower hematocrit and higher Charlson score. (see Table 2)

Figure 1.

Study Enrollment Flowchart

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics - Colorectal Operations

| Fallen in 6-months prior to operation? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Fallers | Non-Fallers | p-value | |

| (n=81) | (n=29) | (n=52) | ||

| Pre-Operative Variables | ||||

| Age (years) | 74±7 | 80±7 | 71±6 | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 10% (8) | 14% (4) | 8% (4) | 0.448 |

| Hypertension | 72% (58) | 66% (19) | 75% (39) | 0.443 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 12% (10) | 14% (4) | 12% (6) | 0.740 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 7% (6) | 7% (2) | 8% (4) | 1.000 |

| Insulin Dependent Diabetes | 7% (6) | 10% (3) | 6% (3) | 0.661 |

| COPD | 20% (16) | 28% (8) | 15% (8) | 0.246 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.2±0.5 | 1.4±0.7 | 1.1±0.2 | 0.023 |

| ASA Score ≥3 | 74% (60) | 93% (27) | 63% (33) | 0.002 |

| Body Mass Index | 25.7±4.8 | 25.3±4.1 | 26.0±5.2 | 0.491 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.7±0.5a | 3.4±0.6 | 3.8±0.4 | 0.006 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 40.0±6.1 | 36.1±5.9 | 42.2±5.1 | <0.001 |

| Charlson Indexb | 2.9±1.7 | 3.9±1.4 | 2.4±1.6 | <0.001 |

| Intra-Operative Variables | ||||

| Laparoscopic (not open) | 47% (38) | 38% (11) | 52% (27) | 0.254 |

| OR Time (minutes) | 178±48 | 169 ±47 | 182±49 | 0.236 |

| Blood Loss (mL) | 183±155 | 208±182 | 170±137 | 0.329 |

| Blood Transfusion (units) | 0.1±0.5 | 0.1±0.5 | 0.1±0.5 | 0.847 |

| Type of Operation | ||||

| Right Colectomy | 30% (24/81) | 27.6% (8/29) | 30.8% (16/52) | 0.805 |

| Left Colectomy | 68% (55/81) | 72.4% (21/29) | 65.4% (34/52) | 0.623 |

| Subtotal Colectomy | 2% (2/81) | 0% | 3.8%(2/52) | 0.535 |

| Disease State | ||||

| Benign | 30% (24/81) | 24% (7/29) | 33% (17/52) | 0.611 |

| Stage 1 | 19% (15/81) | 17% (5/29) | 19% (10/52) | 1.000 |

| Stage 2 | 28% (23/81) | 35% (10/29) | 25% (13/52) | 0.443 |

| Stage 3 | 20%(16/81) | 24% (7/29) | 17% (9/52) | 0.563 |

| Stage 4 | 4% (3/81) | 0% | 6% (3/52) | 0.549 |

The p value compares the groups of fallers and non-fallers.

n=79 because two participants did not have a preoperative albumin level within 30 days of their operation.

Charlson Index is a measure of burden of co-morbidities (range of 0=no co-morbidities, 19=severe co-morbidities).

Abbreviations – COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; OR: operating room.

Table 2.

Baseline Demographics - Cardiac Operations

| Fallen in 6-months prior to operation? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Fallers | Non-Fallers | p-value | |

| (n=154) | (n=49) | (n=105) | ||

| Pre-Operative Variables | ||||

| Age (years) | 74±6 | 76±5 | 72±5 | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 9% (14) | 14% (7) | 7% (7) | 0.141 |

| Hypertension | 90% (139) | 90% (44) | 91% (95) | 1.000 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 66% (102) | 69% (34) | 65% (65) | 0.354 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 20% (31) | 14% (7) | 23% (24) | 0.282 |

| Insulin Dependent Diabetes | 20% (31) | 27% (13) | 17% (18) | 0.199 |

| COPD | 30% (46) | 31% (15) | 30% (31) | 1.000 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.4±0.8 | 1.5±0.9 | 1.4±0.7 | 0.406 |

| ASA Score ≥3 | 96% (147) | 98% (48) | 94% (99) | 0.432 |

| Body Mass Index | 29±5 | 28±5 | 29±5 | 0.662 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.7±0.5a | 3.5±0.5 | 3.8±0.4 | 0.001 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 41±5 | 38±5 | 42±4 | <0.001 |

| Charlson Index | 2.7±1.5 | 3.4±1.5 | 2.3±1.3 | <0.001 |

| Intra-Operative Variables | ||||

| OR Time (minutes) | 314±86 | 314 ±84 | 314±87 | 0.966 |

| Blood Transfusion (units) | 1.1±1.7 | 0.1.3±2.0 | 1.0±1.5 | 0.273 |

| Type of Operation | ||||

| Coronary Artery Bypass | 59% (91) | 63% (31/49) | 57% (60/105) | 0.488 |

| Cardiac Valve | 29% (44) | 22% (11/49) | 31% (33/105) | 0.338 |

| CAB & Valve | 12% (19) | 14% (7/49) | 11% (12/105) | 0.610 |

The p value compares the groups of fallers and non-fallers.

n=152 because two participants did not have a preoperative albumin level within 30 days of their operation.

Abbreviations – COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; OR: operating room; CAB: coronary artery bypass.

Operative characteristics for patients undergoing colorectal and cardiac operations were compared. Type of operation, operative time, blood loss, and transfusion requirements were similar for fallers and non-fallers in both the colorectal (see Table 1) and cardiac (see Table 2) groups. In the colorectal group, disease state was similar in the faller and non-faller groups. (see Table 1)

Postoperative characteristics were compared between the fallers and non-fallers. Preoperative falls were associated with higher incidence of the occurrence of one or more postoperative complications and higher rates of discharge institutionalization in both the colorectal and cardiac groups. (see Table 3) Thirty-day readmission rates were higher in patients with a history of falls following both colorectal (p=0.043) and cardiac (p=0.016) operations. (see Table 3)

Table 3.

Post-Operative Outcomes

| Fallen in 6-months prior to operation? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Fallers | Non-Fallers | p-value | |

| Colorectal Operations | (n=81) | (n=29) | (n=54) | |

| One or more complications | 37% (30) | 59% (17) | 25% (13) | 0.004 |

| Cardiac | 5% (4) | 10% (3) | 2% (1) | |

| Respiratory | 11% (9) | 28% (8) | 2% (1) | |

| Renal | 4% (3) | 7% (2) | 2% (1) | |

| Neurologic | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Infection | 31% (25) | 45% (13) | 23% (12) | |

| Sepsis | 15% (12) | 31% (9) | 6% (3) | |

| DVT | 3% (2) | 7% (2) | 0 | |

| Re-Operation | 10% (8) | 21% (6) | 4% (2) | |

| 30-Day Readmission | 9% (7) | 19% (5) | 4% (2) | |

| Institutionalization | 22% (17) | 52% (14) | 6% (3) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac Operations | (n=154) | (n=49) | (n=105) | |

| One or more complications | 23% (35) | 39% (19) | 15% (16) | 0.002 |

| Cardiac | 3% (5) | 8% (4) | 1% (1) | |

| Respiratory | 5% (7) | 10% (5) | 2% (2) | |

| Renal | 3% (5) | 8% (4) | 1% (1) | |

| Neurologic | 2% (3) | 4% (2) | 1% (1) | |

| Infection | 15% (23) | 25% (12) | 11% (11) | |

| Sepsis | 3% (4) | 4% (2) | 2% (2) | |

| DVT | 1% (2) | 0 | 2% (2) | |

| Re-Operation | 6% (9) | 6% (3) | 6% (6) | |

| 30-Day Readmission | 12% (19) | 23% (11) | 8% (8) | |

| Institutionalization | 41% (62)e | 62% (29) | 32% (33) | 0.001 |

n=79 because two patients died during hospital stay in the colorectal group and neither discharge institutionalization nor 30-day re-admission were applicable

n=151 because three patients died during hospital stay in the cardiac group and neither discharge institutionalization nor 30-day re-admission were applicable

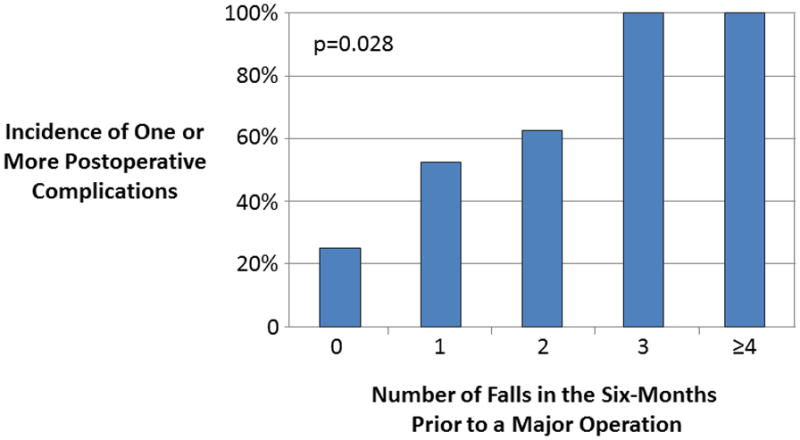

In the bivariable analysis, increasing age (where age is used as a continuous variable) was found to not be associated with the occurrence of one or more postoperative complications in both the colorectal (p=0.509) and cardiac groups (p=0.057). Logistic regression was performed to adjust for the effect of advancing age on the relationship of the occurrence of one or more post-operative complications and having fallen in the six-months prior to the operation. In the colorectal group when age was used as a continuous variable, a history of falls remained associated with the occurrence of one or more complications (OR=7.380; 95% CI: 1.994 to 27.311; p=0.003) and advancing age remained non-significant (p=0.178). In the cardiac group when age was used as a continuous variable, a history of falls remained associated with the occurrence of one or more complications (OR=3.095; 95% CI: 1.361 to 7.042; p=0.007) and advancing age remained non-significant (p=0.326). Because the age of those who had fallen was an average of 9 years greater than the non-fallers in the colorectal group, additional statistical analysis was performed where age was used as a categorical variable (65–69 years, 70–74 years, 75–79 years and the reference group was 80+ years) in the logistic regression model rather than as a continuous variable (results reported above). In the bivariable analysis, increasing age was again not found to be associated with the occurrence of one or more post-operative complications in both the colorectal (p=0.976) and cardiac groups (p=0.228). When adjusting for age, a history of falls remained associated with the outcome (OR=10.214; 95% CI: 2.401 to 43.455; p=0.002) and advancing age remained non-significant in all groups (p=0.319). Adjusting for age in the cardiac group, a history of falls remained associated with the occurrence of one or more complications (OR=3.372; 95% CI: 1.481 to 7.678; p=0.004) and advancing age remained non-significant in all groups. The correlation between the number of fall events in the six-months prior to the operation and the number of complications was determined. There was a positive correlation between number of prior falls and number of complications in both the colorectal (Spearman’s rho=0.411; p<0.001) and cardiac (Spearman’s rho=0.260; p=0.001) groups. (see Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Number of Prior Falls and Postoperative Complications – Colorectal Operations

The ability of a fall history to forecast one or more postoperative complications was compared to currently used methods to assess a patient’s risk including the Charlson score, the ASA score and chronologic age. (see Table 4)

Table 4.

Comparing a Fall History to Established Risk Predictors at Forecasting One or More Postoperative Complications

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COLORECTAL | Lower | Higher | ||

| Positive fall history | 10.436 | 2.214 | 49.193 | 0.003 |

| Charlson Score ≥3 | 7.020 | 1.524 | 32.340 | 0.012 |

| ASA Score ≥3 | 0.116 | 0.024 | 0.563 | 0.008 |

| Age | 0.915 | 0.828 | 1.012 | 0.083 |

| CARDIAC | ||||

| Positive fall history | 2.295 | 0.967 | 5.449 | 0.060 |

| Charlson Score ≥3 | 3.026 | 1.228 | 7.458 | 0.016 |

| ASA Score ≥3 | 0.898 | 0.097 | 8.346 | 0.925 |

| Age | 1.025 | 0.952 | 1.103 | 0.514 |

Discussion

The current study examined the association of a history of falling to postoperative adverse outcomes in individuals 65 years and older undergoing elective colorectal and cardiac operations. The main result is that having fallen in the six months prior to an operation is related to the occurrence of one or more postoperative complications regardless of what procedure is performed. This finding is independent of advancing age in both groups. Having fallen was also associated with increased thirty-day readmission and need for discharge to an institutional care facility. In addition, a positive correlation between an increased number of falls and an increased number of complications exists for both the colorectal and cardiac groups. Finally, having fallen in the six-months prior to an operation was compared to established methods to define a patient’s risk. The history of falls was comparable to the Charlson score, and was favorable to both the ASA score and chronologic age at forecasting one or more postoperative complications.

The concept of a common group of symptoms reflecting the breakdown of frail older adult was first described by Dr. Bernard Isaacs’ four Giants of Geriatrics: incontinence, immobility, instability (falls) and intellectual impairment.11 Gerontologists now recognize five geriatric syndromes (pressure ulcers, incontinence, falls, functional decline, and delirium) to represent symptoms which clinically unify a core geriatric concept.6 While these five clinical presentations are disparate, they all result from an accumulation of subtle impairments across multiple systems. For example, the cause of a fall in an older adult is not due to single cause; but instead results from the interaction of subclinical deficiencies in multiple systems (e.g., decreased proprioception, reduced neuromuscular response, slowed mobility and weakened skeletal muscles). From the standpoint of the clinician, the presence of a geriatric syndrome reflects a frail individual with reduced physiologic reserves and its’ expression may be instigated by acute illness. An example of a geriatric syndrome encountered in the peri-operative setting is when an older adult with appendicitis presents with delirium and not right lower quadrant pain.

Geriatric syndromes have been directly linked to adverse outcomes in hospitalized medical patients. Campbell and colleagues12 performed a multi-center trial studying patients 65 years and older undergoing non-elective medical admissions and found that the presence of the “geriatric giants” (problems with falling, mobility, continence or cognition) prior to admission was at least as important as the presenting diagnosis at forecasting need for discharge institutionalization. Subsequently, Anpalahan and Gibson9 found in 110 medical patients 75 years and older that the presence of a geriatric syndrome (impaired cognition, having fallen, impaired mobility, dependence in an activity of daily living or urinary incontinence) was associated with the occurrence of adverse outcomes (longer length of stay, institutionalization, unplanned three-month readmission and increased three-month mortality). In addition to the geriatric giants, the geriatric syndrome of pressure ulcers has also been related to adverse hospitalized outcomes.13

There is a paucity of data relating pre-existing geriatric syndromes to surgical outcomes. To our knowledge, no study in the literature directly relates geriatric syndromes to surgical outcomes. However, multiple single center studies examine frailty and adverse postoperative outcomes. To quantify frailty, these studies sum the number of frailty characteristics (some of which are geriatric syndromes) present in an older adult prior to an operation. In these studies, the geriatric syndromes of impaired cognition, 7–8, 14–16, poor mobility,7–8, 16–18 incontinence,14 functional decline7–8, 14–15 and having fallen7–8 are abnormal characteristics used in sum to define frailty which has been closely related to adverse postoperative outcomes.

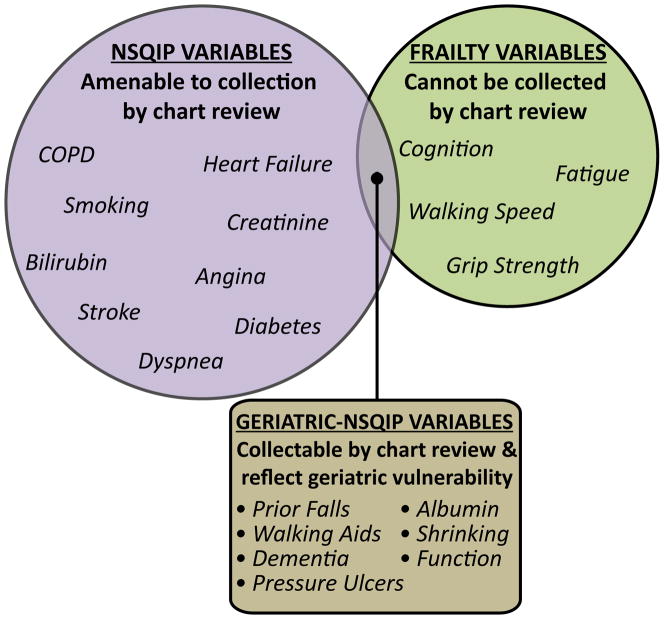

The importance of the current study is twofold. First, this study directly implicates the presence of a geriatric syndrome falling to adverse postoperative outcomes; a finding not altered by the operation performed. Using the presence of geriatric syndromes to forecast adverse postoperative outcomes instead of chronic disease burden or single end-organ dysfunction is a departure from current strategies. Second, a history of falls has the potential to be incorporated into surgical “risk calculators” (the method which most likely represents the future of preoperative risk assessment). The key difference between a fall history and other characteristics which define the frail older adult (e.g., gait speed) is that a history of falls, routinely documented by nursing assessments for inpatient fall risk, can be collected retrospectively from the chart. This property allows such a variable to be recorded in retrospective surgical datasets (e.g., the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, NSQIP, database) from which preoperative risk calculators are developed. The addition of variables specific to geriatric physiologic vulnerability would allow these “risk calculators” to move beyond quantifying surgical risk in older adults using chronic diseases (e.g. hypertension) and single end organ dysfunction (e.g., end stage renal disease) to using frailty characteristics which more appropriately quantify physiologic vulnerability of the older adult. A schematic of additional geriatric-specific variables which can be recorded retrospectively, thereby being amenable to inclusion in retrospective surgical outcome databases, can be found in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Falls and Surgical Outcomes: The First Clue of Surgical Outcomes Database Modifications Needed to Accommodate Older Adults.

The traditional variables used to quantify surgical risk include chronic diseases and single end-organ dysfunction (left side circle in graphic). These variables are amenable to retrospective chart review collection by looking at the surgeon’s history/physical note or the pre-anesthesia evaluation, and as a result are currently used by the NSQIP dataset to forecast surgical risk. Relying solely on chronic disease burden to quantify surgical risk in older adults is inadequate. Frailty-specific variables reveal reduced physiologic reserve specific to the older adult (right side circle in graphic). These frailty variables are not currently used in surgical risk calculators because they are not commonly recorded in the surgical chart, and therefore cannot be collected through retrospective chart review. There are a small number of variables that both quantify the unique physiologic vulnerability of the older adult, and can be collected by retrospective chart review which allows for their inclusion in surgical outcomes datasets (area where two circles overlap). Potential variables to include in a geriatric-specific surgical outcome’s dataset are listed in the graphic’s box. These variables are often accessible by reading nursing inpatient admission notes which include nutrition, mobility, fall and pressure sore risk assessments. Examples of two commonly recorded nursing assessment scales include: [1] the Morse Fall Risk Score (used to quantify inpatient fall risk) documents fall history, ambulatory aid use, gait/transfer difficulties and mental status, and [2] the Braden Score (used to quantify pressure sore risk) documents activity, mobility and nutrition.

There are two main limitations of this study. First, this data shows efficacy and not effectiveness of preoperative falls at forecasting adverse postoperative outcomes. In other words, data on falls collected by a research team focused on quantifying the frail older adult (efficacy) may or may be similar to falls data retrospectively collected out of the nursing notes in the clinical chart (effectiveness). Second, the majority of patients in this study were male; a fact which does not allow a gender bias of the relationship of falls to postoperative outcomes to be detected. The gender distribution of our study reflects the gender distribution of a veteran’s affairs medical center and not selection bias.

Given the high volume of surgical care provide for the elderly population, improving preoperative risk assessment for the older adult is becoming increasingly important. Incorporating geriatric specific variables which reflect physiologic vulnerability of the older adult into large surgical outcomes datasets used to construct preoperative “risk calculators” has real potential to improve the accuracy of these tools at forecasting risk in older adults. A history of falls has the unique property of both being a marker of physiologic frailty and being amenable to retrospective data collection; facts which make a history of falls an ideal candidate for incorporation into large surgical outcomes datasets. Future directions include assessing the relationship of other geriatric specific variables amenable to retrospective chart review to surgical outcomes (see Figure 3) and to begin geriatric specialty collaborative within the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program to test the effectiveness of geriatric specific variables at improving the accuracy of surgical risk calculator for older adults.

Footnotes

The abstract of this manuscript was presented at the American College of Surgeons Annual Clinical Congress on October 1, 2012.

References

- 1.Hall MJ, DeFrances CJ, Williams SN, Golosinskiy A, Schwartzman A. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2007 summary. National health statistics reports. 2010;(29):1–20. 24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobbs F, Stoops N. Commerce USDo, editor. Demographic Trends in the 20th Century. Washington, D.C: 2002. http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/censr-4.pdf ed. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1971–1996. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1968;16(5):622–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, Doucette JT. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273(17):1348–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55(5):780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson TN, Eiseman B, Wallace JI, et al. Redefining geriatric preoperative assessment using frailty, disability and co-morbidity. Annals of surgery. 2009;250(3):449–455. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b45598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson TN, Wallace JI, Wu DS, et al. Accumulated frailty characteristics predict postoperative discharge institutionalization in the geriatric patient. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2011;213(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.056. discussion 42–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anpalahan M, Gibson SJ. Geriatric syndromes as predictors of adverse outcomes of hospitalization. Internal medicine journal. 2008;38(1):16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duthie EH, Katz PR, Malone ML, editors. Practice of Geriatrics: Chapter 17 - Instability and Falls. 4. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isaacs B. The Giants of Geriatrics: A Study of Symptoms in Old Age. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell SE, Seymour DG, Primrose WR, et al. A multi-centre European study of factors affecting the discharge destination of older people admitted to hospital: analysis of in-hospital data from the ACMEplus project. Age Ageing. 2005;34(5):467–475. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alarcon T, Barcena A, Gonzalez-Montalvo JI, Penalosa C, Salgado A. Factors predictive of outcome on admission to an acute geriatric ward. Age Ageing. 1999;28(5):429–432. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dasgupta M, Rolfson DB, Stolee P, Borrie MJ, Speechley M. Frailty is associated with postoperative complications in older adults with medical problems. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;48(1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kristjansson SR, Nesbakken A, Jordhoy MS, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict complications in elderly patients after elective surgery for colorectal cancer: a prospective observational cohort study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;76(3):208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee DH, Buth KJ, Martin BJ, Yip AM, Hirsch GM. Frail patients are at increased risk for mortality and prolonged institutional care after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2010;121(8):973–978. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.841437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2010;210(6):901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afilalo J, Eisenberg MJ, Morin JF, et al. Gait speed as an incremental predictor of mortality and major morbidity in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(20):1668–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]