Abstract

Astrocytes, an abundant form of glia, are known to promote and modulate synaptic signaling between neurons. They also express α7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7-nAChRs), but the functional relevance of these receptors is unknown. We show here that stimulation of α7-nAChRs on astrocytes releases components that induce hippocampal neurons to acquire more a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors post-synaptically at glutamatergic synapses. The increase is specific in that no change is seen in synaptic NMDA receptor clusters or other markers for glutamatergic synapses, or in markers for GABAergic synapses. Moreover, the increases in AMPA receptors on the neuron surface are accompanied by increases in the frequency of spontaneous miniature synaptic currents mediated by the receptors and increases in the ratio of evoked synaptic currents mediated by AMPA versus NMDA receptors. This suggests that stimulating α7-nAChRs on astrocytes can convert ‘silent’ glutamatergic synapses to functional status. Astrocyte-derived thrombospondin is necessary but not sufficient for the effect, while tumor necrosis factor-α is sufficient but not necessary. The results identify astrocyte α7-nAChRs as a novel pathway through which nicotinic cholinergic signaling can promote the development of glutamatergic networks, recruiting AMPA receptors to post-synaptic sites and rendering the synapses more functional.

Keywords: AMPA receptors, astrocytes, cholinergic, glutamatergic, nicotinic, synapse formation

Astrocytes previously thought to provide primarily structural and nutritive support for neurons now are recognized both to modulate neuronal signaling and to support synapse formation (Fellin 2009; Eroglu and Barres 2010; Paixao and Klein 2010; Lo et al., 2011; Clarke and Barres 2013). They can release a variety of neurotransmitters and modulators, including glutamate, GABA, D-serine, and ATP (Fellin et al. 2004; Pascual et al. 2005; Jourdain et al. 2007; Perea and Araque 2007; Gordon et al. 2009; Hamilton and Attwell 2010; Henneberger et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2010; Panatier et al. 2011) and can produce synaptogenic components, including secreted proteins and cholesterol (Mauch et al. 2001; Stellwagon et al. 2005; Garrett and Weiner 2009; Jones et al. 2011; Kucukdereli et al. 2011). Astrocyte components that promote specific aspects of glutamatergic synapse formation include thrombospondin (Christopherson et al. 2005; Eroglu et al. 2009), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα; Beattie et al. 2002; Stellwagon and Malenka 2006; Santello et al. 2011), and glypicans 4/6 (Allen et al. 2012).

Astrocytes express multiple classes of neurotransmitter receptors that may subject astrocytic output to neuronal control. One is the homopentameric α7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7-nAChR; Sharma and Vijayaraghavan 2001; Teaktong et al. 2003; Oikawa et al. 2005; Xiu et al. 2005), which has a high relative permeability to calcium (Bertrand et al. 1993; Seguela et al. 1993), appears early in development (Zhang et al. 1998; Adams et al. 2002; Albuquerque et al. 2009), and regulates many neuronal events in a calcium-dependent manner. These include regulation of transmitter release, enhancement of synaptic plasticity, and control of gene expression (McGehee et al. 1995; Gray et al. 1996; Chang and Berg 2001; Hu et al. 2002; Dajas-Bailador and Wonnacott 2004; Dickinson et al. 2008; Zhong et al. 2008; Albuquerque et al. 2009; Gu and Yakel 2011). Endogenous signaling through α7-nAChRs on neurons also helps determine when GABAergic transmission converts from being excitatory/depolarizing to inhibitory/hyperpolarizing during development (Liu et al. 2006), promotes glutamatergic synapse formation during development (Lozada et al. 2012a, b), and supports maturation and integration of adult-born neurons (Campbell et al. 2010). The significance of α7-nAChRs on astrocytes, however, is unknown.

We show here that activation of α7-nAChRs on astrocytes induces them to secrete components that recruit both GluA1- and GluA2-containing AMPA receptors (GluA1s, GluA2s) to synaptic sites on hippocampal neurons. The recruitment of a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors confers functionality on what appear to be pre-existing, but functionally silent, synapses. Thrombospondin is necessary but not sufficient for the effect, while TNFα is sufficient but not necessary. The results raise the prospect of nicotinic signaling acting through novel astrocytic component(s) to promote maturation of functional glutamatergic networks.

Methods

Cell cultures and conditioned media

Dissociated hippocampal cell cultures were prepared from embryonic day 18 Sprague–Dawley male and female rat embryos as described (Massey et al. 2006). Dissociated astrocyte cultures were prepared from the cerebral cortex of embryonic day 18 rats as described (McCarthy and DeVellis 1980). The astrocyte cultures had no neurons revealed by immunostaining for microtubule-associated protein 2, no NG2-positive cells, and very few microglia as revealed by Iba1 immunostaining (Figure S1; antibodies described below). Astrocyte-conditioned medium (ACM) was generated by replacing the medium on 1-week-old astrocyte cultures with hippocampal culture medium and collecting it 1 week later. ACM from nicotine-treated astrocytes (A/Nic) was prepared identically except that 1 μM nicotine was included during the 1-week incubation prior to collection.

Slice culture

Hippocampal tissue for slice culture was obtained from post-natal day (P) 2 male and female mouse brains as described (Lozada et al. 2012a). Sections (150 μm), obtained with a vibratome, were plated onto Millicell inserts (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) in culture medium (Neurobasal plus 10% horse serum), and incubated at 37°C in a humidified chamber with 5% CO2 for 7 days. The slices were then treated with either ACM or A/Nic, and maintained for seven more days prior to fixation and immunostaining. A sindbis viral construct encoding green fluorescent protein was introduced 12 h before the end of the incubation, using a borosilicate glass microelectrode attached to a Nanoject (Drummond Scientific Company, Broomall, PA, USA) to deliver 70 nL per injection into the CA1 region.

Immunostaining

GluA1s, NR1-containing NMDA receptors (NR1s), and GABAA-α1 receptors on the surface were stained by incubating live cells with rabbit anti-GluA1 antibody (1 : 20; Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ, USA), mouse anti-NR1 antibody (1 : 100; NeuroMab, UC Davis, Davis, CA, USA), or rabbit anti-GABAA-α1 antibody (1 : 200; Alomone, AGA001, Jerusalem, Israel), respectively, on ice for 1 h. GluA2s on the surface were stained by incubating live cells with mouse anti-GluA2 antibody (1 : 100; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) for 15 min in 37°C. Acid wash of intact cells removed the antibody labeling when analyzed subsequently, confirming its confinement to the cell surface. Cells were then washed three times with ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Fixed cells were incubated with antibodies for post-synaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95; 1 : 1000, MA1-045; Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), vesicular glutamate transporter (VGluT; 1 : 1000, AB5905; Millipore), microtubule-associated protein 2 (1 : 5000, ab5392; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), vesicular GABA (Leica Microsystem, Wetzlar, Germany) transporter (VGAT; 1 : 1000, 131004; SyaSys, Goettingen, Germany), glial fibrillary acidic protein (1 : 2000, G3892; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), AMPA receptor subunits GluA 1-4 (GluA; 1 : 500, 182403; SyaSys), Ng-2 (1 : 1000, AB5320; Chemicom, Zug, Switzerland) or Iba1 (1 : 1000, 019-19741; Wako, Osaka, Japan) for 1 h at 21–23°C. Cells were then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated in donkey secondary antibodies (1 : 500; Jackson, West Grove, PA, USA) for 2 h. Fluorescence images were obtained using a Zeiss microscope with 3I software, or with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystem). Labeled puncta number and size were quantified by ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) in a region of interest (20 μm long segment along a dendrite). Labeled puncta were defined as areas containing at least five contiguous pixels with staining above background. Backgrounds were set at three SD above the mean staining intensity of six nearby non-cellular regions. Two puncta were scored as co-localized if they contained at least one pixel in common.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch-clamp recording was performed as described (Zhang and Berg 2007) on hippocampal neurons. For miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents (mEPSCs), neurons in culture were perfused with HEPES-buffered artificial cerebrospinal fluid solution (in mM: NaCl 140, KCl 1, CaCl2 1, HEPES 10, MgCl2 1, glucose 10, with pH adjusted to 7.4). Internal solution contained (in mM): Cs gluconate 122.5, CsCl 10, NaCl 5, MgCl2 1.5, HEPES 5, EGTA 1, Na2-Phosphocreatine 10, MgATP 3, NaGTP 0.3. Data were acquired at 10 kHz. Tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μm) and 20 μm gabazine were included to block action potentials and GABAA receptor-mediated responses, respectively. Neurons were clamped at −70 mV with an Axon 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data were recorded with pClamp 8.0 (Molecular Devices) and analyzed by Mini Analysis Program software (Synaptosoft, Inc., Decatur, GA, USA). For recordings in slices, the bath contained (in mM): NaCl 119, KCl 2.5, CaCl2 2.5, MgSO4 1.3, NaH2PO4 1.0, NaHCO3 26.2, and glucose 11, and was saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2 (to yield pH 7.4). TTX and gabazine were again included when recording mEPSCs. Neurons were clamped at −70 mV with an Axon 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices). Data were recorded with pClamp 9.2 (Molecular Devices). For evoked EPSCs and paired-pulse ratio recordings, a bipolar stimulating electrode was positioned over the Schaffer collaterals ~ 400 μm from the patch-clamped neuron. Gabazine was included to block the GABAA receptors. To compare AMPA and NMDA receptor contributions to EPSCs in the same cell, the AMPA component was recorded as the peak response to a given stimulus at −70 mV, while the NMDA component was taken to be the response 60 ms after the same stimulus but recorded at +40 mV. Blockade of NMDA receptors with the specific antagonist APV caused the stimulus-induced current to decline to 0 mV within 60 ms, confirming that no AMPA-mediated current contaminated the NMDA component at this time (data not shown). Evoked EPSCs were analyzed with Clampfit 9.2 (Molecular Devices).

Immunoblots and immunoprecipitations

Immunoblots were performed as described (Conroy et al. 2003). Briefly, cell samples were scraped in lysis buffer, transferred into sample buffer, boiled, and stored at −20°C before gel electrophoresis and blotting. Blots were probed for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1 : 1000, AB2302; Millipore) to compare protein levels, and for TNFα (1 : 200, N-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and GluA1 (1 : 3000, AB1504, Millipore). Bands were quantified by ImageJ (NIH) Gel Analysis tool. Bradford total protein measurement on the astrocyte plates was done with Bio-Rad Quickstart Bradford protein assay kit (500-0201; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Immunoprecipitation of α7-nAChRs followed by radiolabeled quantification using I125-α-bungarotoxin was performed as described (Conroy et al. 2003; Campbell et al. 2010).

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from primary astrocytic cultures using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Total RNA was eluted by adding 30 μL of RNase-free water onto the silica-gel membrane. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed by using random hexamer primers (RETROscript kit; Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The level of candidate astrocyte-released molecules was assessed via Universal Probe Library Taqman Assays (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) on a Light Cycler 480 system (Roche), as described (Lippi et al. 2011). Primers used were the following (forward and reverse, respectively): TNFα, catcttctcaaaactcgagtg and tgggagtagataaggtacagc; GPC4, caagcactgtctgcaatgatg and aatccgtttcctgtcactgc; GPC6, cacgtttgtgtcaaggcataag and tcgtttagggacttctctgcat; Thbs1, actatgc tggctttgttttcg and ctgggtgacttgtttccaca; Thbs2, agacctcaagtatgagtgcagaga and cgtccaggaaggggtgtt; GAPDH, ggagaaacctgccaagtatga and gtagcccaggatgccctttag. Relative quantification was performed using the comparative DCT method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). Triplicate PCR reactions were made from a single condition, and the experiment repeated four times.

Statistical analysis

Data represent means ± SEMs. Unless otherwise indicated, statistical significance was assessed with Student’s t-test for unpaired values and with one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Materials

Animals were purchased from Harlan Laboratory. All reagents were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise indicated. Soluble TNFα receptor fragment R1 (TNFαR1) was purchased from R&D Systems (636-R1, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Thrombospondin 1 was purchased from Haematologic Technologies (HCTP-0200; Essex Junction, VT, USA). Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). The ARRIVE guidelines have been followed throughout.

Results

A/Nic recruitment of AMPA receptors

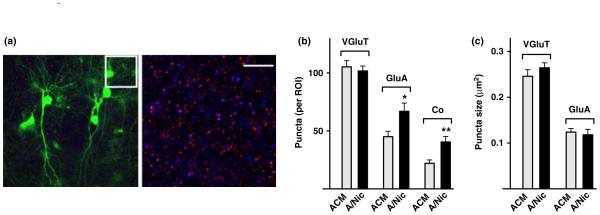

To test whether nAChR stimulation on astrocytes releases synaptogenic components, we incubated astrocyte cultures with 1 μm nicotine for 1 week and then transferred the conditioned medium, A/Nic, to hippocampal slices in organotypic culture. To block direct effects of residual nicotine on the slices, we added the α7-nAChR antagonist methyllycaconitine (MLA, 200 nM) and the β2-containing nAChR antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE, 10 μm) both to the A/Nic and control ACM immediately before application to slices. After a 1-week exposure, we permeabilized and immunostained the slices for AMPA receptor subunits GluA1-4 (GluA) to reveal all AMPA receptor subtypes. We co-stained for the pre-synaptic marker VGluT, scoring co-localization with AMPA receptor puncta as an indicator of glutamatergic synapse number (Fig. 1a) as routinely done (Christopherson et al. 2005; Eroglu et al. 2009; Lozada et al. 2012a, b). Sparse infection with sindbis viral construct encoding green fluorescent protein was used to illuminate individual cells. Slices receiving A/Nic displayed significantly more GluA puncta than did those receiving control ACM (Fig. 1b). No change was seen in the number of VGluT puncta, but the incidence of co-localization for the two was increased by an amount close to the increase in GluA puncta. No change was seen in mean puncta size for either AMPA receptors or VGluT (Fig. 1c). The results suggest that nicotinic stimulation of astrocytes induces them to secrete components that cause hippocampal neurons to generate more AMPA receptor clusters and apparently position more of them at glutamatergic synapses.

Fig. 1.

ACM from nicotine-treated astrocyte (A/Nic) increases the number of α-amino-3-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor puncta in hippocampal slices. P2 slices in culture for 7 days were treated with either astrocyte-conditioned medium (ACM) or A/Nic for an additional 7 days, infected with sindbis viral construct encoding green fluorescent protein (sindbis-GFP) (green), and 12 h later fixed and immunostained for GluA (red) and VGluT (blue). (a) Representative images showing low magnification (left) and high magnification (right; boxed region from left panel) in A/Nic-treated slice. Scale bar: 10 μm. (b) quantification of puncta number per region of interest (ROI) showing a substantial increase in GluA puncta and their co-localization with VGluT puncta, but no change in the overall number of VGluT puncta for A/Nic treatment versus ACM. (c) Sizes of VGluT and GluA puncta, showing no difference between ACM and A/Nic treatments. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01.

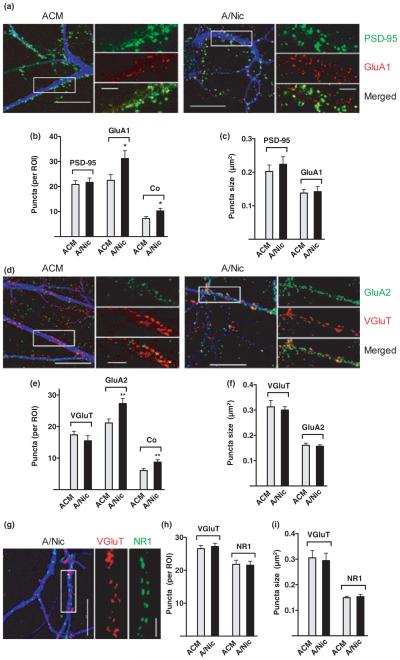

To determine whether the A/Nic-induced increase in GluA puncta specifically included surface receptors, we turned to cell culture. First, comparing A/Nic versus ACM again showed that A/Nic increased the total number of GluA puncta co-localized with VGluT as it did in slice culture and, further, that it also increased the number co-localized with the post-synaptic marker PSD-95 (Figure S2). Labeling only surface GluA1 prior to permeabilizing the cells showed that A/Nic did increase the number of GluA1 puncta on the cell surface and the number at synapses, judging by co-localization with PSD-95 (Fig. 2a–c). In addition, it increased the number of GluA2 puncta and the number at synapses, judged by co-localization with VGluT (Fig. 2d–f). No change was seen in puncta size. Adding nicotine directly to the cells in the presence of MLA and DHβE had no effect on AMPA receptor puncta, ruling out the possibility that residual nicotine in the A/Nic directly acted on hippocampal neurons to produce the observed effects (data not shown). The blockers had no effect on their own (30.5 ± 3.2 vs. 27.7 ± 2.5 for GluA1 puncta number/region of interest in cultures treated with ACM vs. ACM + MLA/DHβE; n = 3 experiments). Interestingly, A/Nic produced no change in the number or size of NR1 puncta (Fig. 2g–i). This suggested that the increase in GluA colocalization with VGluT and PSD-95 represented AMPA receptors appearing at pre-existing glutamatergic synapses that contained NMDA receptors but lacked detectable numbers of AMPA receptors. Consistent with this, A/Nic did not increase the number of VGluT puncta, PSD-95 puncta, or their co-localization, suggesting the total number of glutamatergic synaptic structures had not increased (Fig. 2b, e, h; Figure S3). Also, no change was seen in the number of GABA synapses, judged by total number of VGAT puncta as a pre-synaptic marker, GABAA-α1 puncta as a post-synaptic marker, and their co-localization (Figure S4).

Fig. 2.

ACM from nicotine-treated astrocyte (A/Nic) increases the number of GluA1 and GluA2 puncta on the neuron surface without changing the number of VGluT, post-synaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95), or NR1 puncta. One-week-old hippocampal cultures were incubated with either astrocyte-conditioned medium (ACM) or A/Nic for a week and then live stained for GluA1, GluA2, or NR1 before fixation. Scale bars: 20 μm (left), 5 μm (right). Either the pre-synaptic marker VGluT or the post-synaptic marker PSD-95 was co-stained. (a) Images showing GluA1 (red), PSD-95 (green), and MAP2 (blue). (b) Quantification of puncta number. (c) Mean puncta size. (d) Images showing GluA2 (green), VGluT (red), and MAP2 (blue). (e) quantification of puncta number, and (f) mean puncta size as in (d). (g) Images showing NR1 (green), VGluT (red), and MAP2 (blue). (h) quantification of puncta number, and (i) mean puncta size as in (g). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01.

Nicotinic signaling through astrocytes

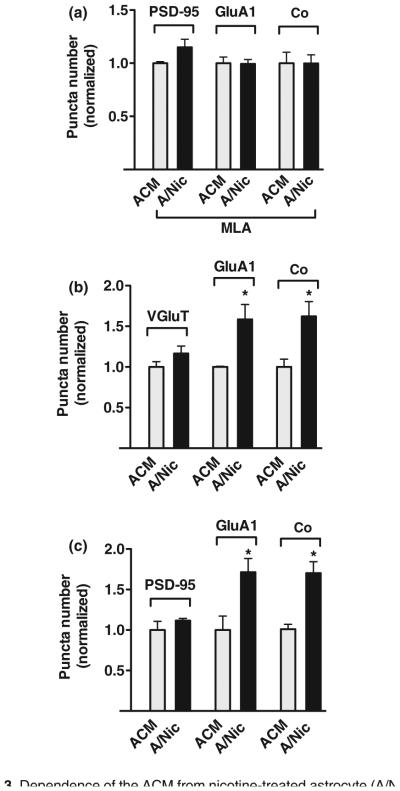

Astrocytes express α7-nAChRs (Sharma and Vijayaraghavan 2001; Teaktong et al. 2003; Oikawa et al. 2005; Xiu et al. 2005). We biochemically confirmed the presence of α7-nAChRs in the astrocyte cultures, using I125-α-bungarotoxin binding and immunoprecipitation (Conroy et al. 2003), obtaining values of 1.27 ± 0.01 fmol/mg protein as opposed to a background value of 0.31 ± 0.03 when nicotine was co-applied with I125-α-bungarotoxin. The nicotine treatment did not change the amount of astrocyte protein as reflected either by GAPDH levels on western blots or by total protein assays (Figure S5). To determine if astrocyte α7-nAChRs were responsible for the effects of A/Nic, we included MLA with nicotine during the production of A/Nic and then transferred the resulting A/Nic/MLA to neuron cultures under normal test conditions. The A/Nic/MLA was not able to increase GluA1 levels on neurons (Fig. 3a). This confirmed that functional α7-nAChRs are necessary for the astrocytes to generate effective A/Nic.

Fig. 3.

Dependence of the ACM from nicotine-treated astrocyte (A/Nic) effect on astrocyte α7-nAChRs, longevity of the induced increase in GluA1 puncta, and the continuing responsiveness of cultures. (a) A/Nic obtained from astrocytes treated with methyllycaconitine (MLA) was unable to increase the number of GluA1 puncta or their co-localization with post-synaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) puncta over the usual 1-week period in hippocampal cultures (values normalized to astrocyte-conditioned medium (ACM)/MLA: 16.2 ± 0.2 puncta/region of interest (ROI) for PSD-95, 15.5 ± 0.9 for GluA1, and 7.1 ± 0.7 for co-localization), indicating the requirement for astrocyte α7-nAChRs. (b) Cultures treated with A/Nic under the normal protocol and then continued an additional week in standard culture medium (no ACM or A/Nic) still displayed the A/Nic-induced increase in GluA1 puncta and their co-localization with vesicular glutamate transporter (VGluT) puncta increase (normalized to ACM: 15.7 ± 0.9 puncta/ROI for VGluT, 13.3 ± 0.1 for GluA1, and 6.8 ± 0.6 for co-localization), indicating the stability of the effect. (c) Hippocampal cultures receiving A/Nic during their third week showed the same increase in GuA1 puncta and co-localization with PSD-95 as did cultures receiving A/Nic during their second week (normalized to ACM, 18.8 ± 2.0 puncta/ROI for PSD-95, 14.1 ± 2.4 for GluA1, and 7.4 ± 0.4 for co-localization), illustrating the continuing responsiveness of the cells to A/Nic. *p ≤ 0.05.

A short-term exposure to A/Nic was insufficient to elevate GluA1 puncta. Applying A/Nic to hippocampal cultures for 1 day either at the beginning or at the end of the week-long incubation period produced no change in the number of GluA1 puncta compared to those in cultures receiving ACM for the entire week (data not shown). The full week-long exposure to A/Nic did, however, have long-lasting effects as seen by replacing the A/Nic with control medium at the end of the normal incubation period, and continuing the cultures for an additional week prior to immunostaining. In such cases, A/Nic-treated cultures displayed the same elevations in GluA1 puncta and co-localization with VGluT puncta seen immediately after A/Nic removal (Fig. 3b). In addition, the hippocampal cultures remain responsive to A/Nic effects at subsequent times. Applying the A/Nic to hippocampal cultures during the third week (instead of second week) yielded the same increases in GluA1 puncta (Fig. 3c).

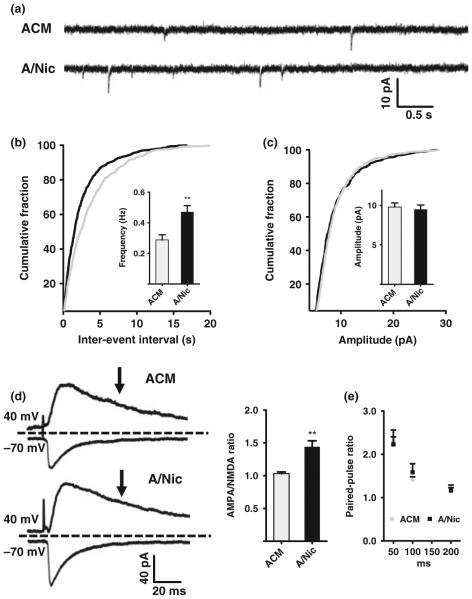

A/Nic-induced increases in glutamatergic transmission

If A/Nic recruits AMPA receptors to synapses previously lacking them, this would be expected to score as an increase in the number of functional synapses and produce an increase in the frequency of mEPSCs. To test this, we used patch-clamp recording to monitor mEPSCs in the presence of TTX and gabazine to block action potentials and GABAA receptors, respectively. Neurons treated with A/Nic for 1 week in cell culture had significantly more events than those receiving ACM, with no change in mean amplitude (Figure S6). We then examined hippocampal slices in organotypic culture. Again A/Nic exposure for 1 week significantly increased mEPSC frequency without changing mean amplitude (Fig. 4a–c), consistent with more glutamatergic synapses being functional. The effects of A/Nic were not because of residual nicotine directly acting on neuronal receptors because the routine addition of MLA and DHβE immediately prior to applying the A/Nic and ACM to neurons blocked direct action. Confirmation of this was obtained by finding that addition of 1 μm nicotine directly to hippocampal cultures for 1 week produced a 53 ± 16% (n = 4; p ≤ 0.05) increase in the frequency of mEPSCs compared to controls, whereas inclusion of MLA and DHβE along with the nicotine prevented the increase (2 ± 8% over controls; n = 4). The A/Nic-induced increase in mEPSC frequency is consistent with an increase in the number of functional glutamatergic synapses because of recruitment of AMPA receptors.

Fig. 4.

ACM from nicotine-treated astrocyte (A/Nic) increases the a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) component of glutamatergic transmission. (a) Patch-clamp recordings of miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents (mEPSCs) in organotypic slices at −70 mV in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing 1 μm tetrodotoxin (TTX) and 10 μm gabazine. quantification of AMPA receptor-mediated mEPSC frequency (b) and amplitude (c) in astrocyte-conditioned medium (ACM) and A/Nic-treated slices. (d) Left: Patch-clamp recordings of evoked EPSCs at −70 mV and +40 mV in ACSF containing 10 μm gabazine. Right: Ratio of evoked EPSC amplitudes for the AMPA peak component at -70 mV and NMDA component at +40 mV, 60 ms after the stimulus. A/Nic, increased the ratio, compared to ACM. (e) Paired-pulse ratios of evoked EPSC amplitudes at the indicated intervals for cells treated with A/Nic versus ACM revealed no differences, suggesting equivalent release probabilities. **p ≤ 0.01.

An additional prediction is that A/Nic treatment should increase the proportion of whole-cell evoked EPSC amplitude caused by AMPA receptors, as opposed to NMDA receptors. This was tested in slices by using a bipolar stimulating electrode to evoke synaptic currents in the presence of gabazine after the 1-week treatment with A/Nic or ACM (Fig. 4d). The peak response at −70 mV was used to assess the AMPA component. The response in the same cell at +40 mV after the AMPA current had diminished, i.e. at 60 ms post-stimulus, was used for the NMDA component. Comparing the ratio of AMPA/NMDA components in this manner indicated that A/Nic-treated neurons had a substantially higher relative contribution of AMPA receptors to evoked EPSCs than found in ACM-treated neurons (Fig. 4d). These A/Nic-induced effects on mEPSCs and evoked EPSCs were unlikely to represent differences in the probability of glutamate release because the paired-pulse ratio measured at several intervals was found to be equivalent under the two conditions (Fig. 4e). The results indicate that A/Nic increases the contribution of AMPA receptors to EPSCs, and may do so by rendering previously silent synapses functional.

A/Nic candidate components

Synaptogenic components known to be secreted by astrocytes and relevant for glutamatergic synapses include TNFα, which can recruit AMPA receptors to post-synaptic sites (Beattie et al. 2002; Stellwagon and Malenka 2006; Santello et al. 2011), and the glypicans 4/6 which specifically recruit GluA1-containing AMPA receptors to synapses (Allen et al. 2012). Another astrocyte-secreted component, thrombospondin, can promote glutamatergic synapse formation on retinal ganglion cells in culture, but the synapses appear to lack AMPA receptors (Christopherson et al. 2005; Eroglu et al. 2009). We first used qPCR analysis to determine whether the extended nicotine treatment elevated transcript levels for any of these candidate proteins in astrocytes. No significant differences were seen in TNFα, glypicans 4/6, or thrombospondin 1 or 2 mRNA levels in nicotine-treated astrocytes versus controls (1.1 ± 0.3, 1.0 ± 0.1, 1.0 ± 0.1, 1.1 ± 0.2, and 0.9 ± 0.2 for TFNα, glypicans 4/6, and thrombospondin 1 and 2, respectively, for A/Nic values normalized to those in ACM). Enhanced availability of these components through nicotine-induced transcriptional up-regulation in astrocytes is unlikely to account for the A/Nic affect.

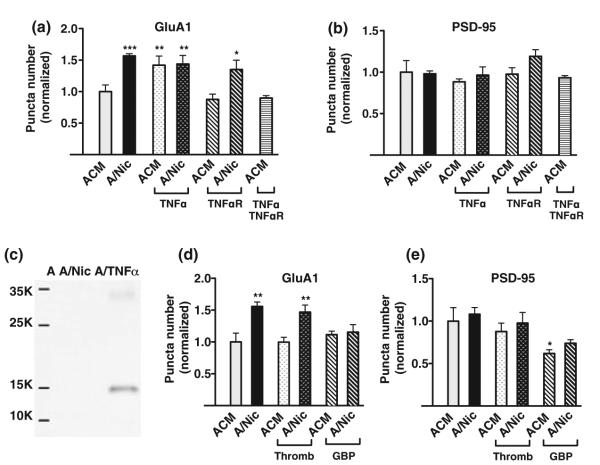

Because TNFα was a logical component for mediating the A/Nic-induced increase in AMPA receptors, given its ability to recruit AMPA receptors to synapses (Beattie et al. 2002; Stellwagon and Malenka 2006; Santello et al. 2011), we tested the protein directly. Adding TNFα to ACM did increase the number of GluA1 puncta, equivalent in magnitude to that obtained with A/Nic (Fig. 5a). When added to A/Nic, however, TNFα did not further increase the number of GluA1 puncta. More telling were blockade experiments with an extracellular domain fragment of the TNFα receptor, namely TNFαR1 which absorbs TNFα and blocks its action (Stellwagon et al. 2005; Santello et al. 2011). Adding TNFαR1 to the culture medium completely prevented the increase in GluA1 puncta caused by TNFα added to ACM but had no effect on the equivalent increase produced by A/Nic (Fig. 5a). None of the manipulations had any effect on PSD-95 puncta (Fig. 5b). Moreover, western blot analysis failed to detect significant TNFα either in ACM or in A/Nic, though the blot analysis readily detected the amount of TNFα added to ACM and A/Nic in the culture experiments (Fig. 5c). These results exclude TNFα as the component in A/Nic responsible for elevating the number of AMPA receptor puncta on hippocampal neurons.

Fig. 5.

Neither tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) nor thrombospondin can account for the unique synaptogenic properties of ACM from nicotinetreated astrocyte (A/Nic). Hippocampal cultures were incubated with astrocyte-conditioned medium (ACM) or A/Nic plus the indicated compounds for 7 days and then quantified for the indicated puncta revealed by immunostaining. (a) Effects of TNFα, TNFαR, and the two together on GluA1 puncta in ACM-versus A/Nic-treated cultures, normalized for ACM ±20.3 ± 2.01 puncta/region of interest (ROI)]. (b) Effects of (a) conditions on post-synaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) puncta, normalized for ACM (19.9 ± 2.79 puncta/ROI). (c) Western blots indicating relative amounts of TNFα in ACM (A), A/Nic, and the 100 ng/mL TNFα added to the culture medium (A/TNFα). (d) Effects of thrombospondin (Thromb) and gabapentin (GBP) as a thrombospondin blocker, added with either ACM or A/Nic to the cultures for 1 week and then immunostained for GluA1 and normalized to ACM (23.4 ± 3.25 puncta/ROI). (e) Conditions as in (d) but immunostained for PSD-95 and normalized for ACM (21.9 ± 3.5 puncta/ROI). TNFα replicated the effects of A/Nic on GluA1 puncta but was not the component responsible for them, and thromobospondin was necessary for the effects of A/Nic but did not alone produce them. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001

Thrombospondin, in contrast, appears to be necessary but not sufficient to produce the A/Nic effect. When thrombospondin was added directly to ACM, it produced no increase in either the number of GluA1 puncta (Fig. 5d) or PSD-95 puncta (Fig. 5e), indicating that it was unlikely to be the active component in A/Nic responsible for the GluA1 increase. Gabapentin, a specific blocker of thrombospondin synaptogenic effects in retinal ganglion cell culture (Eroglu et al. 2009), however, did prevent A/Nic from increasing the number of GluA1 puncta (Fig. 5d). Furthermore, gabapentin decreased the number of PSD-95 puncta seen in ACM, though it did not reduce the number of GluA1 puncta seen in ACM (Fig. 5e). This is consistent with thrombospondin increasing the number of glutamatergic synaptic structures which serve as scaffolds for A/Nic to assign AMPA receptors, converting the structures to functional synapses. In this sense thrombospondin can be considered necessary but not sufficient for the A/Nic effect.

Discussion

Astrocytes are increasingly found to play unexpected roles in modulating synaptic transmission and supporting synapse formation (Araque et al. 2001; Newman 2003; Volterra and Steinhauser 2004; Barres 2008; Allen et al. 2012; Clarke and Barres 2013). The results presented here show for the first time that activation of α7-nAChRs on astrocytes induces them to release components that increase the number of AMPA receptor clusters on neurons and to localize the clusters at post-synaptic sites. Neurons expressing these additional post-synaptic AMPA receptors both in cell culture and in organotypic slices display a higher frequency of spontaneous mEPSCS, consistent with the cells having an increased number of functional glutamatergic synapses. Furthermore, neurons under these conditions in slice culture display a larger AMPA receptor-mediated component of their whole-cell EPSC, relative to the NMDA receptor-mediated component. No change was seen in GABAergic synapses or in several structural components of glutamatergic synapses, namely VGluT, PSD-95, and NMDA receptors. The results suggest a new and unique role for astrocytes in promoting functional maturation of existing glutamatergic synapses.

The immunostaining methods used to quantify synaptic contacts based on juxtaposed pre- and post-synaptic markers are in widespread use for these purposes (Christopherson et al. 2005; Stevens et al. 2007; Eroglu et al. 2009; Lozada et al. 2012a, b). The results showed increases in the numbers of both GluA1 and GluA2 puncta associated with the presynaptic glutamatergic marker VGluT and the post-synaptic marker PSD-95 on neurons grown in A/Nic, compared to ACM alone. Particularly striking, however, was the observation that A/Nic treatment did not change the total numbers of VGluT, PSD-95, and NR1 puncta or their incidence of pair-wise co-localization, where examined. Importantly, A/Nic both increased the frequency of mEPSCs without changing mean mEPSC amplitude and increased the ratio of AMPA receptor versus NMDA receptor contributions to evoked EPSCs. These results suggest that a number of glutamatergic contacts (presumptive synapses) had formed in the absence of A/Nic but lacked sufficient AMPA receptors to mediate synaptic transmission. Sustained exposure to the astrocyte components in A/Nic enabled the neurons to recruit AMPA receptors to such sites, rendering them functional. Consistent with this, A/Nic did not increase the mean size of GluA1 or GluA2 puncta, only their number. The results suggest that A/Nic acts on ‘silent synapses’, previously described as a platform for induction of long-term potentiation (Isaac et al. 1995; Liao et al. 1995) converting them to functional status.

The effects of A/Nic did not represent an acute direct action of residual nicotine on the neurons. This was excluded by adding the nicotinic blockers MLA and DHβE along with the A/Nic to hippocampal cultures. The effectiveness of the blockers was confirmed by showing that nicotine added directly to the cultures in the presence of the blockers did not alter mEPSC frequency. Glia express multiple classes of nicotinic receptors (Sharma and Vijayaraghavan 2001; Xiu et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2007), including α3*-containing nAChRs which are thought to trigger nitric oxide production (MacEachern et al. 2011). The generation of A/Nic capable of increasing AMPA receptor levels clearly depended on astrocyte α7-nAChRs. This was demonstrated by showing that the α7-nAChR blocker MLA prevented nicotine from enabling astrocytes to produce effective A/Nic. At the concentration used, MLA would block only α7-nAChRs and rare α6-containing nAChRs; the latter appear to be absent from the hippocampus (Klink et al. 2001; Dani and Bertrand 2007), and not reported for astroctyes.

Endogenous nicotinic activation of α7-nAChRs has recently been shown necessary for normal acquisition of glutamatergic synapses both in the hippocampus and cortex during development (Lozada et al. 2012a). That α7-nAChR effect was cell-autonomous, requiring the receptors to be expressed by the post-synaptic neuron, and it affected multiple aspects of glutamatergic synapses as revealed by immunostaining for synaptic markers and recording synaptic activity. The A/Nic effect reported here differs in being dependent on astrocyte α7-nAChRs and specifically promoting appearance of AMPA receptor clusters at what are likely to be pre-existing but non-functional glutamatergic synapses.

How might astrocyte α7-nAChRs induce the release of synaptogenic components? The high relative calcium permeability of α7-nAChRs (Bertrand et al. 1993; Seguela et al. 1993) enables them to activate a variety of calciumdependent processes, including transmitter release from presynaptic terminals (McGehee et al. 1995; Gray et al. 1996; Dajas-Bailador and Wonnacott 2004; Dickinson et al. 2008; Albuquerque et al. 2009). Astrocytes are capable of calciuminduced calcium release, potentially augmenting calcium effects (Sharma and Vijayaraghavan 2001). Calcium-dependent release of components from astrocytes, however, is still controversial (Hamilton and Attwell 2010). An alternative possibility is that α7-nAChR activation changes gene transcription (Chang and Berg 2001; Hu et al. 2002; Dajas-Bailador and Wonnacott 2004; Albuquerque et al. 2009), promoting greater availability of the component(s) for constitutive release.

What might the component(s) be? TNFα can increase AMPA receptors levels and is released by astrocytes (Beattie et al. 2002; Stellwagon and Malenka 2006; Santello et al. 2011). It cannot, however, account for the effects of A/Nic seen here. While adding TNFα to ACM did mimic the effects of A/Nic, inactivation of TNFα by co-incubation with TNFαR1 did not block A/Nic. TNFαR1 did, in contrast, prevent the effects of TNFα added to ACM, confirming the effectiveness of the blocker. Moreover, western blot analysis failed to detect TNFα either in ACM or A/Nic, though it readily detected the TNFα added in the culture experiments. Accordingly, TNFα cannot be considered the component in A/Nic responsible for the recruitment of AMPA receptors.

Glypicans 4/6 were reported to be released by astrocytes and capable of increasing the number of GluA1s on retinal ganglion cells (Allen et al. 2012). Their effects differ, however, from those of A/Nic. Glypicans 4/6 increase both mEPSC frequency and amplitude, whereas A/Nic affects only frequency and not amplitude. Furthermore, the glypicans fail to increase GluA2 receptors, unlike A/Nic, and they are relatively fast acting, achieving effects within 24 h whereas A/Nic requires multiple days. PCR analysis of astrocytes revealed no nicotine-induced differences in glypicans 4/6 transcription levels. Taken together, the results indicate that glypicans 4/6 are unlikely to be responsible for the A/Nic effect.

A final astrocyte component considered here was thrombospondin. It too is made and released by astrocytes, and can induce glutamatergic synapses on retinal ganglion cells, though the synapses appear to be deficient in AMPA receptors (Christopherson et al. 2005; Eroglu et al. 2009). Thrombospondin added either to ACM or to A/Nic had no effect on the number of AMPA receptor clusters, indicating it was not the relevant component. Adding the blocker gabapentin to A/Nic, however, did prevent A/Nic from increasing the number of AMPA receptor clusters. A likely explanation was provided by the observation that gabapentin also reduced the number of PSD-95 puncta supported by ACM. The results suggest that ACM contains thrombospondin and that it is likely to be responsible for at least some of the PSD-95-containing glutamatergic precursor synapses but is not itself responsible for the additional AMPA receptor puncta induced by A/Nic. Rather, those precursor synapses may be an obligatory platform for accumulating the AMPA receptor clusters induced by A/Nic, as noted above. Accordingly, thrombospondin appears to be necessary but not sufficient for the A/Nic effect. Though astrocytes are known to release a variety of components (see Introduction), no other obvious candidates have been identified, with the possible exception of hevin which, like thrombospondin, can recruit synaptic components but not AMPA receptors (Kucukdereli et al. 2011).

Astrocytes are widely expressed in the CNS, and cholinergic projections extend across the brain early on, driving waves of excitation (Bansal et al. 2000; Hanson and Landmesser 2003, 2006; Myers et al. 2005; Le Magueresse et al. 2006; Witten et al. 2010). If volume transmission is a common occurrence for cholinergic signaling (Descarries et al. 1997; Umbriaco et al. 1995), the amount and duration of agonist exposure could approach those achieved here with nicotine. As a result, endogenous signaling through astrocyte α7-nAChRs must be considered a potentially important factor determining the formation of functional glutamatergic pathways. Notably, this could extend to the adult nervous system as well, contributing to plasticity by recruiting AMPA receptors to synaptic sites. In line with this, A/Nic was still found to be effective when applied to more mature neuronal cultures, e.g. those in which GABAergic signaling would have been inhibitory. The effects of astrocyte α7-nAChRs on synaptic plasticity in adult pathways will be an important issue for the future.

The concentration of nicotine used here was in the range found in heavy smokers (Rose et al. 2010). Because nicotine can be sequestered in the fetus during pregnancy, even higher concentrations may be experienced by the embryo (Luck et al. 1985; Wickström 2007). Early exposure to nicotine is known to have long-lasting behavioral effects (Laviolette and van der Kooy 2004; Albuquerque et al. 2009; Gotti et al. 2009; Heath and Picciotto 2009; Changeux 2010). Excessive stimulation of astrocyte α7-nAChRs by tobacco-derived nicotine at early times may account for a substantial part of those effects, given the impact it has on glutamatergic synapse formation. An important challenge for the future will be assessing the biomedical consequences of early nicotine exposure on developmental events regulated by astrocytes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest. We thank Xiao-Yun Wang and Jeff Schoellerman for expert technical assistance, and Andrew Halff for confirming nicotinic receptors on astrocytes. Grant support was provided by the US National Institutes of Health (NS012601, NS034569, and DA034216) and the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (16KT-011617, FT-0053, and 19XT-0072).

Abbreviations

- A/Nic

ACM from nicotine-treated astrocyte

- ACM

astrocyte-conditioned medium

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- ANOVA

one-way analysis of variance

- CNQX

6-cyano-7-nitroqui-noxaline-2,3-dione

- DHβE

dihydro-β-erythroidine

- GAPDH

glyceral-dehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GluA1s

GluA1-containing AMPA receptors

- GluA2s

GluA2-containing AMPA receptors

- GluA

AMPA receptor subunits GluA1-4

- MAP2

microtubule-associated protein 2

- mEPSCs

miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents

- MLA

methyllycaconitine

- NR1s

NR1-containing NMDA receptors

- P

post-natal day

- ROI

region of interest

- sindbis-GFP

sindbis viral construct encoding green fluorescent protein

- TNFαR1

TNFα receptor fragment R1

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-α

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- VGAT

vesicular GABA transporter

- VGluT

vesicular glutamate transporter

- α7-nAChRs

α7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

Footnotes

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

References

- Adams CE, Broide RS, Chen Y, Winzer-Serhan UH, Henderson TA, Leslie FM, Freedman R. Development of the α7 nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat hippocampal formation. Dev. Brain Res. 2002;139:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque EX, Pereira EFR, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 2009;89:73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NJ, Bennett ML, Foo LC, Wang GX, Chakraborty C, Smith SJ, Barres BA. Astrocyte glypicans 4 and 6 promote formation of excitatory synapses via GluA1 AMPA receptors. Nature. 2012;486:410–414. doi: 10.1038/nature11059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Carmignoto G, Haydon PG. Dynamic signaling between astrocytes and neurons. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2001;63:795–813. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal A, Singer JH, Hwang B, Feller MB. Mice lacking specific nAChR subunits exhibit dramatically altered spontaneous activity patterns and reveal a limited role for retinal waves in forming ON/OFF circuits in the inner retina. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7672–7681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07672.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres BA. The mystery and magic of glia: a perspective on their roles in health and disease. Neuron. 2008;60:430–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie EC, Stellwagen D, Morishita W, Bresnahan JC, Ha BK, Zastrow MV, Beattie MX, Malenka RC. Control of synaptic strength by glial TNFα. Science. 2002;295:2282–2285. doi: 10.1126/science.1067859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D, Galzi JL, Devillers-Thiéry A, Bertrand S, Changeux JP. Mutations at two distinct sites within the channel domain M2 alter calcium permeability of neuronal alpha 7 nicotinic receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:6971–6975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell NR, Fernandes CC, Halff AW, Berg DK. Endogenous signaling through α7-containing nicotinic receptors promotes maturation and integration of adult-born neurons in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:8734–8744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0931-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K, Berg DK. Voltage-gated channels block nicotinic regulation of CREB phosphorylation and gene expression in neurons. Neuron. 2001;32:855–865. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00516-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux J-P. Nicotine addiction and nicotinic receptors: lessons from genetically modified mice. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:389–401. doi: 10.1038/nrn2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson KS, Ullian EM, Stokes CC, Mullowney CE, Hell JW, Agah A, Lawler J, Mosher DF, Bornstein P, Barres BA. Thrombospondins are astrocyte-secreted proteins that promote CNS synaptogenesis. Cell. 2005;120:421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke LE, Barres BA. Emerging roles of astrocytes in neural circuit development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013;14:311–312. doi: 10.1038/nrn3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy WG, Liu Q-s, Nai Q, Margiotta JF, Berg DK. Potentiation of α7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by select albumins. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;63:419–428. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dajas-Bailador F, Wonnacott S. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and the regulation of neuronal signalling. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;25:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;47:699–729. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descarries L, Gisiger V, Steriade M. Diffuse transmission by acetylcholine in the CNS. Prog. Neurobiol. 1997;53:603–625. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson JA, Kew JN, Wonnacott S. Presynaptic alpha 7- and beta 2-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors modulate excitatory amino acid release from rat prefrontal cortex nerve terminals via distinct cellular mechanisms. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;74:348–359. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.046623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu C, Barres BA. Regulation of synaptic connectivity by glia. Nature. 2010;468:223–231. doi: 10.1038/nature09612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu C, Allen NJ, Susman MW, et al. Gabapentin receptor a2d-1 is a neuronal thrombospondin receptor responsible for excitatory CNS synaptogenesis. Cell. 2009;139:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin T. Communication between neurons and astrocytes: relevance to the modulation of synaptic and network activity. J. Neurochem. 2009;108:533–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin T, Pascual O, Gobbo S, Pozzan T, Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Neuronal synchrony mediated by astrocytic glutamate through activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2004;43:729–743. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett AM, Weiner JA. Control of CNS synapse development by c-protocadherin-mediated astrocyte-neuron contact. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:11723–11731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2818-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon GR, Iremonger KJ, Kantevari S, Ellis-Davies GC, MacVicar BA, Bains JS. Astrocyte-mediated distributed plasticity at hypothalmic glutamate synapses. Neuron. 2009;64:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Clementi F, Fornari A, Gaimarri A, Guiducci S, Manfredi I, Moretti M, Pedrazzi P, Pucci L, Zoli M. Structural and functional diversity of native brain neuronal nicotinic receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009;78:703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray R, Rajan AS, Radcliffe KA, Yakehiro M, Dani JA. Hippocampal synaptic transmission enhanced by low concentrations of nicotine. Nature. 1996;383:713–716. doi: 10.1038/383713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Yakel JL. Timing-dependent septal cholinergic induction of dynamic hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2011;71:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton NB, Attwell D. Do astrocytes really exocytose neurotransmitters? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:227–238. doi: 10.1038/nrn2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MG, Landmesser LT. Characterization of the circuits that generate spontaneous episodes of activity in the early embryonic mouse spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:587–600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00587.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MG, Landmesser LT. Increasing the frequency of spontaneous rhythmic activity disrupts pool-specific axon fasciculation and pathfinding of embryonic spinal motoneurons. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:12769–12780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4170-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath CH, Picciotto MR. Nicotine-induced plasticity during development: modulation of the cholinergic system and long-term consequences for circuits involved in attention and sensory processing. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneberger C, Papoulin T, Oliet SH, Rusakov DA. Long-term potentiation depends on release of D-serine from astrocytes. Nature. 2010;463:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature08673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Liu QS, Chang KT, Berg DK. Nicotinic regulation of CREB activation in hippocampal neurons by glutamatergic and nonglutamatergic pathways. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2002;21:616–625. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac JTR, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Evidence for silent synapses: implications for the expression of LTP. Neuron. 1995;15:427–434. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EV, Bernardinelli Y, Tse YC, Chierzi S, Wong TP, Murai KK. Astrocytes control glutamate receptor levels at developing synapses through SPARC-b-integrin interactions. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:4154–4165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4757-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdain P, Bergersen LH, Bhaukaurally K, Bezzi P, Santello M, Domercq M, Matute C, Tonello F, Gundersen V, Volterra A. Glutamate exocytosis from astrocytes controls synaptic strength. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:331–339. doi: 10.1038/nn1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klink R, de Kerchove d’Exaerde A, Zoli M, Changeux J-P. Molecular and physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the midbrain dopaminergic nuclei. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1452–1463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01452.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucukdereli H, Allen NJ, Lee AT, et al. Control of excitatory CNS synaptogenesis by astrocyte-secreted proteins Hevin and SPARC. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:E440–E449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104977108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviolette SR, van der Kooy D. The neurobiology of nicotine addiction: bridging the gap from molecules to behavior. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:55–65. doi: 10.1038/nrn1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Magueresse C, Safiulina V, Changeux J-P, Cherubini E. Nicotinic modulation of network and synaptic transmission in the immature hippocampus investigated with genetically modified mice. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2006;576:533–546. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.117572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Yoon B-E, Berglund K, Oh S-J, Park H, Shin H-S, Augustine GJ, Lee CJ. Channel-mediated tonic GABA release from glia. Science. 2010;330:790–796. doi: 10.1126/science.1184334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Hessler NA, Malinow R. Activation of postsynaptically silent synapses during pairing-induced LTP in CA1 region of hippocampal slice. Nature. 1995;375:400–404. doi: 10.1038/375400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi G, Steinert JR, Marczylo EL, Fiore R, D’Oro S, Forsythe ID, Schratt G, Zoli M, Nicotera P, Young KW. Targeting of the Arpc3 actin nucleation factor by microRNA-29a/b regulates dendritic spine morphology. J. Cell Biol. 2011;194:889–904. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Neff RA, Berg DK. Sequential interplay of nicotinic and GABAergic signaling guides neuronal development. Science. 2006;314:1610–1613. doi: 10.1126/science.1134246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-CT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo FS, Zhao S, Erzurumlu RS. Astrocytes promote peripheral nerve injury-induced reactive synaptogenesis in the neonatal CNS. J. Neurophysiol. 2011;106:2876–2887. doi: 10.1152/jn.00312.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozada AF, Wang X, Gounko NV, Massey KA, Duan J, Liu X, Berg DK. Glutamatergic synapse formation is promoted by α7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Neurosci. 2012a;32:7651–7661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6246-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozada AF, Wang X, Gounko NV, Massey KA, Duan J, Liu X, Berg DK. Induction of dendritic spines by β2-containing nicotinic receptors. J. Neurosci. 2012b;32:8391–8400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6247-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck W, Nau H, Hansen R, Steldinger R. Extent of nicotine and cotinine transfer to the human fetus, placenta and amniotic fluid of smoking mothers. Dev. Pharmacol. Ther. 1985;8:384–395. doi: 10.1159/000457063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacEachern SJ, Patel B, McKay DM, Sharkey KA. Nitric oxide regulation of colonic epithelial ion transport: a novel role for enteric glia in the myenteric plexus. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2011;589:3333–3348. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.207902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey K, Zago WM, Berg DK. BDNF up-regulates nicotinic receptor levels on subpopulations of hippocampal interneurons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2006;33:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauch DH, Nagler K, Schumacher S, Goritz C, Muller E-C, Otto A, Pfrieger FW. CNS synaptogenesis promoted by glia-derived cholesterol. Science. 2001;294:1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5545.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy KD, DeVellis J. Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J. Cell Biol. 1980;85:890–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee D, Heath MJ, Gelber S, Role LW. Nicotine enhancement of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in CNS by presynaptic receptors. Science. 1995;269:1692–1696. doi: 10.1126/science.7569895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers CP, Lewcock JW, Hanson MG, Gosgnach S, Aimone JB, Gage FH, Lee KF, Landmesser LT, Pfaff SL. Cholinergic input is required during embryonic development to mediate proper assembly of spinal locomotor circuits. Neuron. 2005;46:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA. New roles for astrocytes: regulation of synaptic transmission. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:536–542. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikawa H, Nakamichi N, Kambe Y, Ogura M, Yoneda Y. An increase in intracellular free calcium ions by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in single cultured rat cortical astrocytes. J. Neurosci. Res. 2005;79:535–544. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paixao S, Klein R. Neuron-astrocyte communication and synaptic plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010;20:466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panatier A, Vallee J, Haber M, Murai KK, Lacaille J-C, Robitaille R. Astrocytes are endogenous regulators of basal transmission at central synapses. Cell. 2011;146:785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual O, Casper KB, Kubera C, Zhang J, Revilla-Sanchez R, Sul JY, Takano H, Moss SJ, McCarthy K, Haydon PG. Astrocytic purinergic signaling coordinates synaptic networks. Science. 2005;310:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1116916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea G, Araque A. Astrocytes potentiate transmitter release at single hippocampal synapses. Science. 2007;317:1083–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1144640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Mukhin AG, Lokitz SJ, Turkington TG, Herskovic J, Behm FM, Garg S, Garg PK. Kinetics of brain nicotine accumulation in dependent and nondependent smokers assessed with PET and cigarettes containing 11C-nicotine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2010;107:5190–5195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909184107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santello M, Bezzi P, Volterra A. TNFα controls glutamatergic gliotransmission in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neuron. 2011;69:988–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguela P, Wadiche J, Dineley-Miller K, Dani JA, Patrick JW. Molecular cloning, functional properties, and distribution of rat brain alpha 7: a nicotinic cation channel highly permeable to calcium. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:596–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G, Vijayaraghavan S. Nicotinic cholinergic signaling in hippocampal astrocytes involves calcium-induced calcium release from intracellular stores. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:4148–4153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071540198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellwagon D, Malenka RC. Synaptic scaling mediated by glial TNA-α. Nature. 2006;440:1054–1059. doi: 10.1038/nature04671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellwagon D, Beattie EC, Seo JY, Malenka RC. Differential regulation of AMPA receptor and GABA receptor trafficking by tumor necrosis factor-α. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:3219–3228. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4486-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens B, Allen NJ, Vazquez LE, et al. The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell. 2007;131:1164–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaktong T, Graham A, Court J, Perry R, Jaros E, Johnson M, Hall R, Perry E. Alzheimer’s disease is associated with a selective increase in alphα7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor immunoreactivity in astrocytes. Glia. 2003;41:207–211. doi: 10.1002/glia.10132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbriaco D, Garcia S, Beaulieu C, Descarries L. Relational features of acetylcholine, noradrenaline, serotonin and GABA axon terminals in the stratum radiatum of adult rat hippocampus (CA1) Hippocampus. 1995;5:605–620. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450050611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volterra A, Steinhauser C. Glial modulation of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Glia. 2004;47:249–257. doi: 10.1002/glia.20080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang ZY, Wang Y. Expression of alphα7-nAChR on rat hippocampal astrocytes in vivo and in vitro. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2007;27:591–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickström R. Effects of nicotine during pregnancy: human and experimental evidence. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2007;5:213–222. doi: 10.2174/157015907781695955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten IB, Lin SC, Brodsky M, Prakash R, Diester I, Anikeeva P, Gradinaru V, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K. Cholinergic interneurons control local circuit activity and cocaine conditioning. Science. 2010;330:1677–1681. doi: 10.1126/science.1193771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu J, Nordberg A, Zhang J-T, Guan ZZ. Expression of nicotinic receptors on primary cultures of rat astrocytes and up-regulation of the alphα7, alpha4 and beta2 subunits in response to nanomolar concentrations of the beta-amyloid peptide. Neurochem. Int. 2005;47:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Berg DK. Reversible inhibition of GABAA receptors by alphα7-containing nicotinic receptors on vertebrate postsynaptic neurons. J. Physiol. 2007;579:753–763. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Liu C, Miao H, Gong Z-H, Nordberg A. Postnatal changes in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α2, α3, α4, α7 and β2 subunits genes expression in rat brain. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 1998;16:507–518. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(98)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong C, Du C, Hancock M, Mertz M, Talmage DA, Role LW. Presynaptic type III neuregulin 1 is required for sustained enhancement of hippocampal transmission by nicotine and for axonal targeting of alphα7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:9111–9116. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0381-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.