Abstract

Objective:

This article discusses why CSF biomarkers found in normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) can be misleading when distinguishing NPH from comorbid NPH with Alzheimer disease (AD).

Methods:

We describe NPH CSF biomarkers and how shunt surgery can change them. We hypothesize the effects that hydrocephalus may play on interstitial fluid space and amyloid precursor protein (APP) fragment drainage into the CSF based on a recent report and how this may explain the misleading CSF NPH biomarker findings.

Results:

In NPH, β-amyloid protein 42 (Aβ42) is low (as in AD), but total tau (t-tau) and phospho-tau (p-tau) levels are normal, providing conflicting biomarker findings. Low Aβ42 supports an AD diagnosis but tau findings do not. Importantly, not only Aβ42, but all APP fragments and tau proteins are low in NPH CSF. Further, these proteins increase after shunting. An increase in interstitial space and APP fragment drainage into the CSF during sleep was reported recently.

Conclusions:

In the setting of hydrocephalus when the brain is compressed, a decrease in interstitial space and APP protein fragment drainage into the CSF may be impeded, resulting in low levels of all APP fragments and tau proteins, which has been reported. Shunting, which decompresses the brain, would create more room for the interstitial space to increase and protein waste fragments to drain into the CSF. In fact, CSF proteins increase after shunting. CSF biomarkers in pre-shunt NPH have low Aβ42 and tau protein levels, providing misleading information to distinguish NPH from comorbid NPH plus AD.

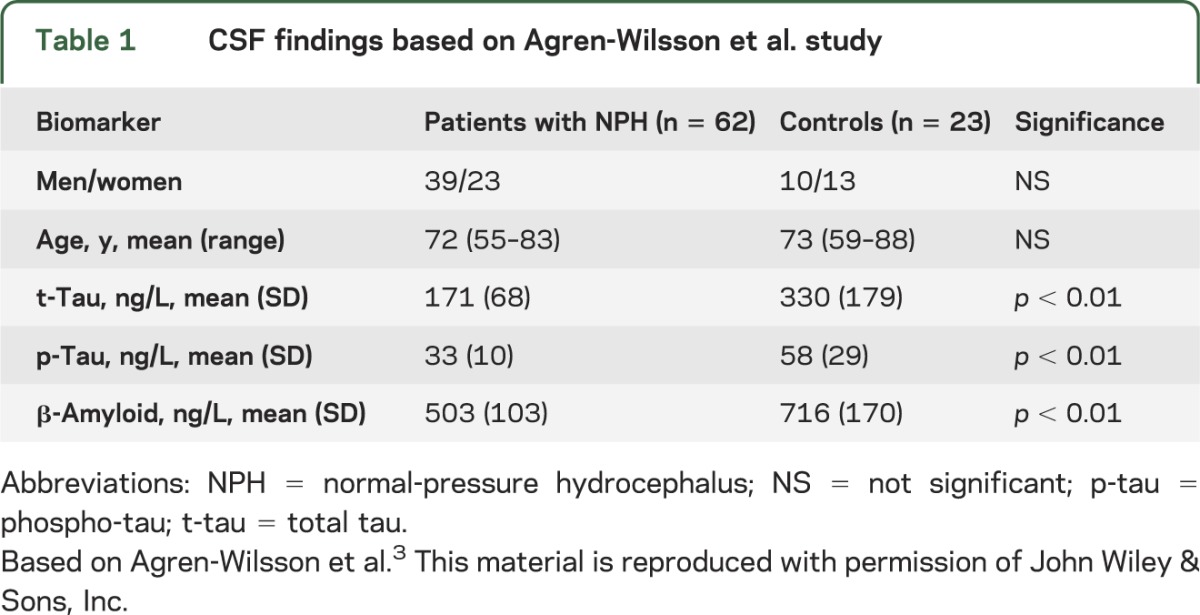

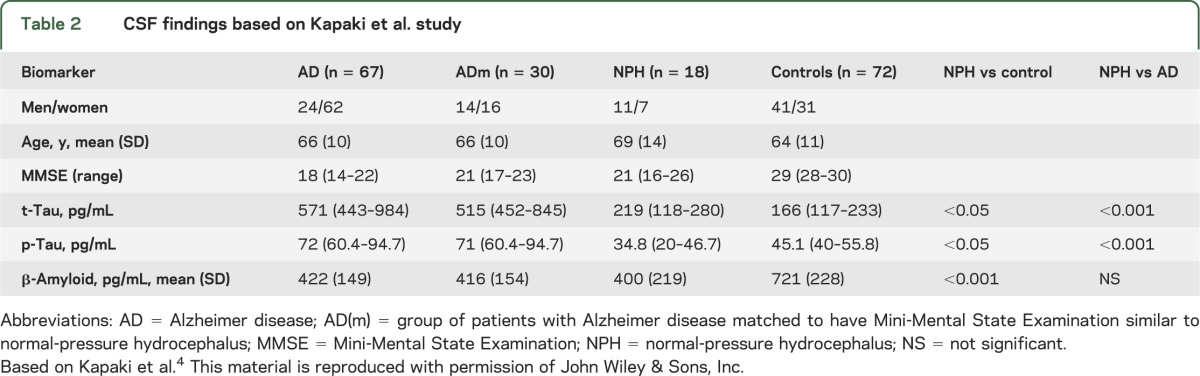

To date, CSF biomarkers have not been helpful in distinguishing patients with normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) from those with NPH and comorbid Alzheimer disease (AD). The landmark article by Xie et al.1 may provide an explanation for this. In AD, CSF characteristically has low β-amyloid 42 (Aβ42) and high total tau (t-tau) and phospho-tau (p-tau) levels.2 The low Aβ42 is thought to reflect brain Aβ42 deposition, while the high t-tau and p-tau levels indicate nerve cell and nerve ending (neurite) damage. In NPH, CSF has similar low Aβ42 as in AD, but t-tau and p-tau levels are not increased as in AD. In fact, the levels are similar to those in normal controls.3,4 See tables 1 and 2 based on articles by Agren-Wilsson et al.3 and Kapaki et al.,4 respectively, which we chose because they have large numbers of patients and controls to compare.

Table 1.

CSF findings based on Agren-Wilsson et al. study

Table 2.

CSF findings based on Kapaki et al. study

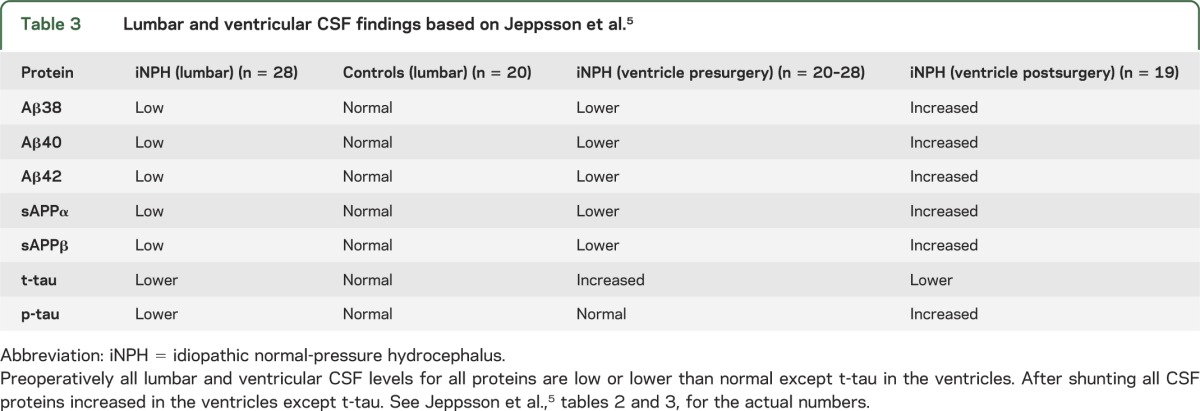

A recent article by Jeppsson et al.5 confirmed that NPH has low CSF Aβ42 and t-tau and p-tau, but their study went further, showing that all the amyloid precursor protein (APP) fragments (Aβ38, Aβ40, Aβ42, sAPPα, and sAPPβ) were low in NPH CSF. In addition, they showed that levels of these proteins were all lower in the ventricle than the lumbar CSF. Importantly, after shunting, all the proteins (except t-tau) increased in the ventricle CSF (table 3).

Table 3.

Lumbar and ventricular CSF findings based on Jeppsson et al.5

Jeppsson et al.5(p1387) speculated that the low protein levels that increased with shunting may have had one of two explanations:

…reduced production of APP-derived proteins, possibly due to reduced brain metabolism in the periventricular zone, as seen in PET and MRI studies. Another possible explanation for the observed reductions in Aβ peptide and soluble APP fragment and tau protein levels could be reduced clearance from extracellular fluid due to reduced centripetal flow of extracellular fluid caused by the retrograde CSF dynamics in iNPH.

DISCUSSION

Let us now analyze how the Xie et al.1 report may reflect on this problem. They point out that the brain lacks a conventional lymphatic system, yet CSF interchanges with interstitial fluid (ICF) and removes interstitial proteins, including APP fragments. The CSF fluid enters the brain in spaces around the arteries, and the ICF leaves along pathways adjacent to veins. This is called the glymphatic system. Xie et al. found that Aβ clearance from the ICF is increased during sleep because at that time, the interstitial space increases 60% in size. This occurs because cells shrink during sleep but upon awakening return to their normal size. The increase cell size is mediated by the noradrenergic pathways. We hypothesize in the setting of NPH where the brain is tight in the skull (as supported by imaging findings called disproportionate enlarged subarachnoid hydrocephalus in the Japanese NPH studies and guideline in which they show imaging evidence of tight sulci over the convex6), it is likely that the extracellular space is smaller and has less room to expand during sleep. This would compromise convective CSF/ICF fluxes and APP fragment clearance. This is in keeping with the Jeppsson et al.5 report (see table 3); specifically, all APP fragments and tau proteins are low prior to shunt surgery. Thus in NPH, the low CSF Aβ42 (and other APP fragments) are not necessarily related to Aβ brain deposition, but rather could be from impaired clearance. The low tau proteins have the same explanation. When the patient has a shunt placed, the CSF levels of almost all the proteins increase (see table 3), likely due to room for the ICF space to increase during sleep and the ability for the proteins to better drain into the CSF.

The hypothesis proposed in this article does not exclude the hypothesis proposed by Jeppsson et al. They suggest that periventricular hypometabolism seen on PET and MRI may also play a role in having low APP fragments in NPH CSF.

CSF AD-related biomarkers are not useful in separating patients with NPH from those with comorbid AD. The low CSF Aβ42, t-tau, and p-tau are likely because these fragments cannot drain adequately from the ICF into the CSF when the patient has hydrocephalus. Doctors should not rely on AD CSF biomarkers to differentiate NPH from NPH with comorbid AD. Prospective Aβ brain PET studies should be evaluated to determine if these distinguish NPH from comorbid NPH with AD and it would be interesting to compare amyloid PET with CSF biomarkers. Further, good standardization of CSF biomarkers should be accomplished for future CSF biomarker studies.7,8

GLOSSARY

- Aβ42

β-amyloid 42

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- ICF

interstitial fluid

- NPH

normal-pressure hydrocephalus

- p-tau

phospho-tau

- t-tau

total tau

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURE

N. Graff-Radford has been on the Scientific Advisory Committee of Codman, but there is no conflict related to this article. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 2013;342:373–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blennow K, Hampel H. CSF markers for incipient Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol 2003;2:605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agren-Wilsson A, Lekman A, Sjoberg W, et al. CSF biomarkers in the evaluation of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neurol Scand 2007;116:333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapaki EN, Paraskevas GP, Tzerakis NG, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau, phospho-tau181 and beta-amyloid1-42 in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: a discrimination from Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Neurol 2007;14:168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeppsson A, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Wikkelso C. Idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus: pathophysiology and diagnosis by CSF biomarkers. Neurology 2013;80:1385–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mori E, Ishikawa M, Kato T, et al. Guidelines for management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: second edition. Neurol Med Chir 2012;52:775–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klinge P, Berding G, Brinker T, Weckesser E, Knapp WH, Samii M. Regional cerebral blood flow profiles of shunt-responder in idiopathic chronic hydrocephalus: a 15-O-water PET-study. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2002;81:47–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanderstichele H, Bibl M, Engelborghs S, et al. Standardization of preanalytical aspects of cerebrospinal fluid biomarker testing for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis: a consensus paper from the Alzheimer's Biomarkers Standardization Initiative. Alzheimers Dement 2012;8:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]