Abstract

Objective:

In the current exploratory study, we longitudinally measured immune parameters in the blood of individuals with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS), and investigated their relationship to disease duration and clinical and radiologic measures of CNS injury.

Methods:

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and plasma were obtained from subjects with RRMS, SPMS, and from healthy controls on a monthly basis over the course of 1 year. MRI and Expanded Disability Status Scale evaluations were performed serially. PBMCs were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay to enumerate myelin basic protein–specific interleukin (IL)-17- and interferon (IFN)-γ-producing cells. Plasma concentrations of proinflammatory factors were measured using customized Luminex panels.

Results:

Frequencies of myelin basic protein–specific IL-17- and IFN-γ-producing PBMCs were higher in individuals with RRMS and SPMS compared to healthy controls. Patients with SPMS expressed elevated levels of IL-17–inducible chemokines that activate and recruit myeloid cells. In the cohort of patients with SPMS without inflammatory activity, upregulation of myeloid-related factors correlated directly with MRI T2 lesion burden and inversely with brain parenchymal tissue volume.

Conclusions:

The results of this exploratory study raise the possibility that Th17 responses and IL-17–inducible myeloid factors are elevated during SPMS compared with RRMS, and correlate with lesion burden. Our data endorse further investigation of Th17- and myeloid-related factors as candidate therapeutic targets in SPMS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS), an inflammatory disease of the CNS, typically presents with a relapsing-remitting course. During this early stage of disease, peripheral blood leukocytes cross the blood-brain barrier to drive the formation of demyelinating plaques. Disease-modifying agents (DMAs) that modulate or suppress the peripheral immune system provide therapeutic benefit in relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).1

The majority of individuals with RRMS ultimately enter a secondary progressive (SP) stage, characterized by gradual accumulation of neurologic disability independent of clinical relapses. The cellular and molecular basis for this transition is unclear, and the role of inflammation during the SP stage is a subject of considerable debate. DMAs lose efficacy after transition to SPMS,2,3 prompting the hypothesis that clinical deterioration in SPMS is driven by a neurodegenerative process, possibly unconnected to the autoimmune assault that predominates earlier.4 In contrast, a growing body of data suggests that immune dysregulation is a salient feature of progressive MS, although the proinflammatory pathways involved and consequent pattern of injury differ from those that typify relapsing forms of the disease.5–13 In the current study, we performed immune assays on plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) serially collected from individuals with RRMS, SPMS, and healthy controls (HCs). In parallel, patients with MS were monitored via the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and cranial MRI scans to investigate associations between immune abnormalities and disease progression.

METHODS

Subjects and clinical assessments.

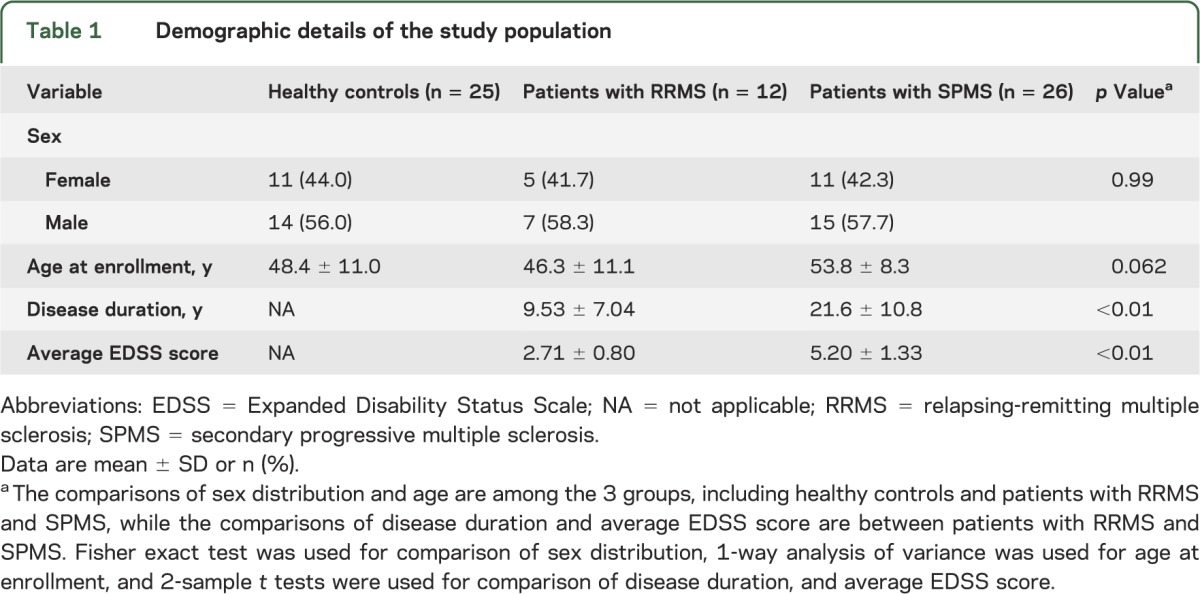

Patients with RRMS (n = 12) and SPMS (n = 26) were recruited from the Multiple Sclerosis Clinics at the University of Rochester and the University of Michigan. More complete demographic details are displayed in table 1. Patients were diagnosed with RRMS or SPMS based on the revised McDonald Diagnostic Criteria and clinical course.14 Secondary progression was defined by a progressive increase in disability (of at least 6 months' duration) in the absence of relapses. Based on our inclusion/exclusion criteria, subjects with SPMS had not experienced a clinical relapse or had an MRI scan demonstrating a gadolinium-enhancing lesion within 2 years of study enrollment. Blood was collected from study subjects and from 25 age- and sex-matched HCs on a monthly basis. Every patient with MS underwent EDSS scoring by a board-certified neurologist blinded to the results of MRI scanning and immune assays. Cranial MRI and clinical assessments were performed every other month and every third month, respectively, on all 38 patients with MS. None of the participants experienced a clinical relapse or received corticosteroids during the 1-year study. Six of 12 patients with RRMS had at least one enhancing lesion on one or more MRI scans. Three of the 12 had a significant increase in T2 lesion burden between initial and final MRI scans; all 3 had enhancing lesions on multiple MRI scans.

Table 1.

Demographic details of the study population

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The institutional review boards of the University of Michigan and the University of Rochester approved our study protocol. All study subjects provided written informed consent after the nature and possible consequences of the study were explained.

Cell preparation.

PBMCs were isolated from the blood of patients and HCs using CPT Vacutainer tubes (BD, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). PBMCs were suspended in fetal bovine serum with 20% dimethyl sulfoxide and stored in liquid nitrogen until thawed for enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assays. Plasma was stored at −80°C until thawed for Luminex assays.

ELISPOT assays.

Ninety-six–well, filter-bottom plates (MSIPN4W; Millipore, Billerica, MA) were coated with anti-IFN-γ or anti-IL-17A antibodies at 3 μg/mL (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). PBMCs were plated at 1–5 × 105 cells per well either alone or with whole human myelin basic protein (MBP) (50 μg/mL; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or tetanus toxoid (1.5 μg/mL; Fisher Scientific). In preliminary studies, PBMCs were plated across serial dilutions to determine the optimal conditions for eliciting reproducible antigen-specific responses in the linear range of the dose-response curve. Plates were incubated for 24 hours (interferon [IFN]-γ) or 48 hours (interleukin [IL]-17) at 37°C with 5% CO2 after which they were washed and incubated with biotinylated detection antibodies (eBioscience) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). Plates were developed with the Vector alkaline phosphatase substrate kit (SK5300; Vector, Burlingame, CA). Spots were counted and analyzed using the ImmunoSpot analyzer (Cellular Technology Limited, Shaker Heights, OH). All assays were performed in triplicate and data were normalized to 106 cells/well. Technicians performing ELISPOT assays were blinded to the identity of patients.

Luminex assays.

Plasma levels of cytokines and chemokines were measured with customized multiplex magnetic bead-based arrays (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Data were collected using the Bio-Plex 200 system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Standards were run in parallel to allow quantification of individual factors. The data shown indicate levels that fell within the linear portion of the corresponding standard curve. Technicians performing Luminex assays were blinded to the identity of patients.

MRI protocol and image analysis.

All patients were evaluated with cranial MRI examination on a 1.5-tesla–strength magnet using axial T2-weighted and axial and sagittal T1-weighted sequences. Brain parenchymal and CSF volumes and T2 lesion load were measured using commercially available software developed by VirtualScopics (Rochester, NY). This involved coregistering each MRI to a presegmented anatomical atlas with manual refinement of automated brain boundaries by an expert analyst where necessary, as previously described.15 Lesion boundaries were identified in 3 dimensions using geometrically constrained region growth.15,16 T2 lesion volume was normalized to total brain parenchymal tissue volume.

Statistical analysis.

Descriptive analyses were conducted to examine group differences among HCs and patients with RRMS and SPMS for demographic variables. Summary statistics were computed for continuous measures as mean ± SD, and for categorical variables as frequency and proportion (%). One-way analysis of variance was used to assess whether group differences existed among the 3 cohorts for continuous variables (age), and Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables (sex). EDSS and disease duration are not relevant to HCs, and were compared only between patients with RRMS vs SPMS using 2-sample t tests. Personal average and personal variation over a 1-year observation period were calculated for immune parameters of interest. We evaluated group differences in personal average and personal variance using Wilcoxon nonparametric tests, considering the limited group-specific sample sizes and the fact that some of the distributions are skewed. The group-specific mean longitudinal trajectories of plasma levels of chemokines and neutrophil elastase were assessed and compared using linear mixed models with random effects to account for within-subject correlations. When fitting longitudinal models, more observations were available because of repeated measurements for each patient, and we were able to adjust for the effect of age when appropriate. Comparisons were made between chemokine levels and disease duration, EDSS, T2 lesion volume, or brain parenchymal tissue volume using all available measurements. The analysis was performed using within-cluster resampling methodology, considering the concern of the intraclass correlation. Specifically, we randomly chose one observation per patient, and calculated Spearman correlations. This process was repeated 200 times, and we merged all 200 estimated correlations to obtain the final results using established methods.17,18 Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the R 2.15.2 software program.

RESULTS

MBP-specific IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing PBMCs are prevalent in RRMS and SPMS.

Prior studies on the frequency of autoreactive T cells in MS are conflicting; some investigators report a significantly higher incidence of myelin-specific PBMCs in individuals with MS compared with age- and sex-matched HCs, while others report no significant difference.19–23 Most are cross-sectional studies that used proliferation or IFN-γ production as a measure of antigenic responsiveness.19 Because Th1 and Th17 cells have both been implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmune demyelination,24 we revisited this question by performing both IFN-γ and IL-17 ELISPOT assays on PBMCs collected longitudinally over the course of 1 year from individuals with RRMS or SPMS in comparison to HCs. None of the patients with SPMS were receiving treatment with a DMA or had received a DMA within the last year. The same was true for 7 of 12 subjects with RRMS; the remainder had been treated with glatiramer acetate for 3 months or longer at the time of enrollment, and remained on this medication through the duration of the study. For each assay, personal average and variation were calculated across multiple blood samples from each subject, thereby minimizing the introduction of artifact produced by spurious background fluctuations in immune parameters.

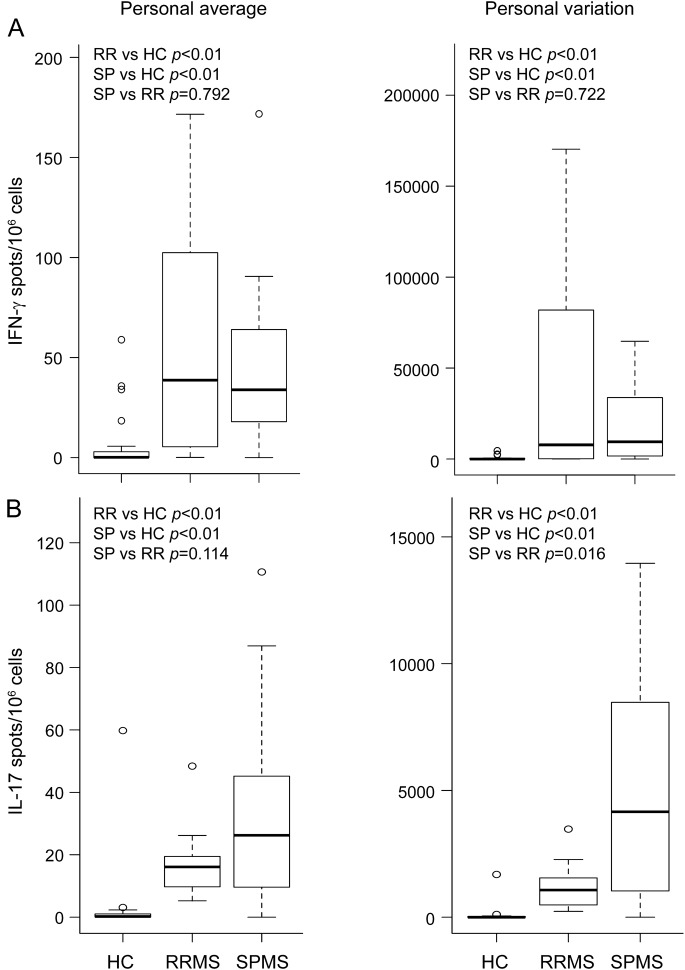

We found that the mean frequencies of PBMCs that produced IL-17 or IFN-γ in response to challenge with MBP were higher in subjects with RRMS or SPMS than in HCs (figure 1, left panels). MBP-reactive IL-17–producing cells tended to be more abundant in SPMS than RRMS, although this difference fell short of statistical significance (p = 0.114). The mean frequency of MBP-reactive IL-17, but not IFN-γ, producers correlated with disease duration when the data were analyzed across all patients with MS (R = 0.323, p = 0.05). The same was true of the Th17 polarizing monokine, IL-23 (R = 0.366, p = 0.026). Personal variation of both the IL-17 and IFN-γ responses were greater in the MS cohorts (figure 1, right panels). There was no significant difference in cytokine responses between untreated patients with RRMS and those treated with glatiramer acetate, or between patients recruited in Rochester and those recruited in Michigan (data not shown). Our results appeared specific for MBP-reactive cells, because the mean frequency and variance of tetanus toxoid–reactive IL-17- and IFN-γ-producing PBMCs were comparable across all 3 cohorts (figure e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org).

Figure 1. Frequencies of MBP-reactive IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing PBMCs are elevated in RRMS and SPMS compared with HCs.

PBMCs were collected from individuals with RRMS (n = 12) and SPMS (n = 26) as well as from HCs (n = 25) on a monthly basis over the course of 1 year. PBMCs were analyzed using ELISPOT to measure the frequencies of MBP-reactive IFN-γ (A) and IL-17 (B) producers. To determine antigen specificity, the number of spots counted in wells without antigen was subtracted from the corresponding spots in MBP-pulsed wells. Mean frequency (left panels) and variation (right panels) were calculated for each subject from all blood samples collected during the course of the study. Wilcoxon nonparametric tests were used to determine statistical significance, in consideration of the limited group-specific sample sizes and the fact that some of the distributions are skewed. ELISPOT = enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot; HC = healthy control; IFN = interferon; IL = interleukin; MBP = myelin basic protein; PBMC = peripheral blood mononuclear cell; RR = relapsing-remitting; RRMS = relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; SP = secondary progressive; SPMS = secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Plasma levels of myeloid factors increase with disease duration and EDSS score.

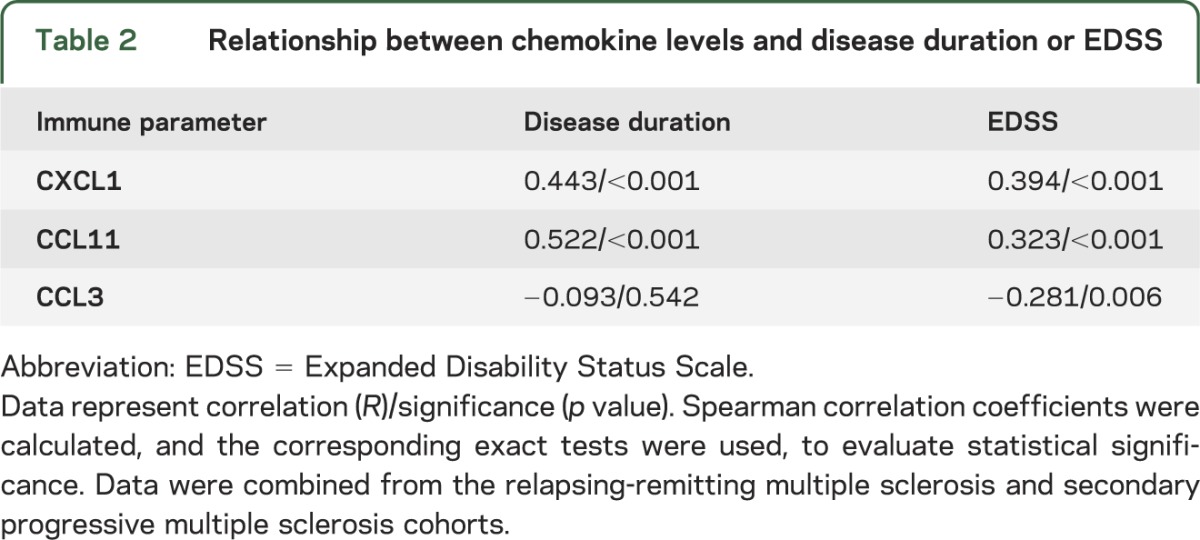

The above data suggest that autoreactive Th17 responses are prominent late in the course of MS. Innate immune dysregulation has been described in SPMS.7–11,25,26 A major biological function of IL-17 is to stimulate the production of chemokines and growth factors that activate, mobilize, and recruit myeloid cells to sites of inflammation, including CXCL1 and CCL11.24,27,28 We found that mean plasma levels of CXCL1 and CCL11 increased with disease duration when data were analyzed across all patients with MS (table 2). In contrast, there was no significant correlation between length of disease and expression of CCL3.

Table 2.

Relationship between chemokine levels and disease duration or EDSS

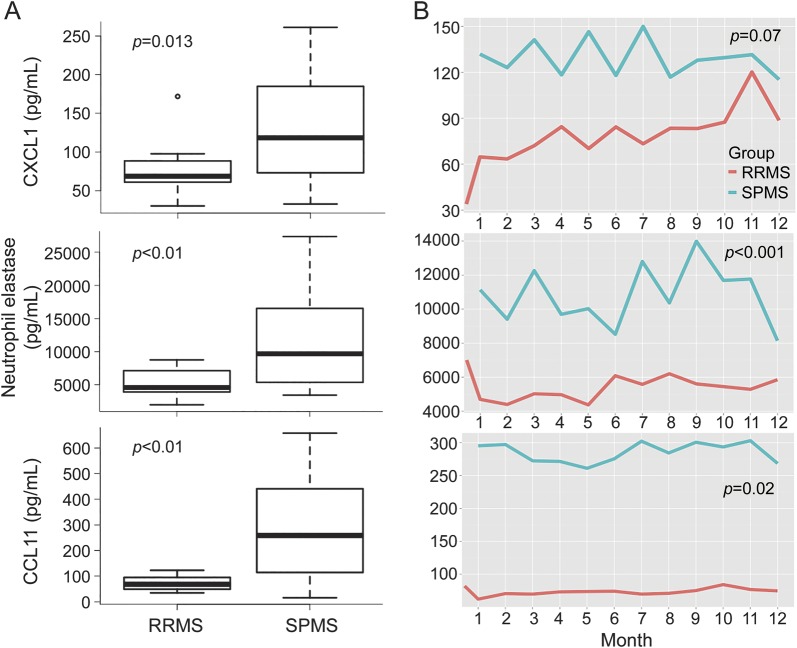

Participants in our longitudinal study underwent an EDSS assessment at the time of enrollment and every 3 months thereafter. Plasma levels of CXCL1 and CCL11 also directly correlated with EDSS score (table 2). Conversely, CCL3 inversely correlated with EDSS. Based on these results, we compared the expression of myeloid factors in RRMS and SPMS. Mean plasma levels of CXCL1 and CCL11, as well as neutrophil elastase (a marker of neutrophil activity), were all significantly higher in patients with SPMS compared to those with RRMS (figure 2). Similar to our results with MBP-specific PBMC responses, expression of CXCL1, CCL11, and neutrophil elastase did not differ significantly between untreated and glatiramer acetate–treated patients with RRMS, or between patients recruited from different sites (data not shown).

Figure 2. IL-17–inducible, myeloid-related factors are expressed at significantly higher levels in SPMS compared with RRMS.

The levels of the indicated immune parameters were averaged over all plasma samples collected from each subject with RRMS or SPMS during the course of the study. The box plots show the mean personal average of patients in each cohort (A). Longitudinal expression of CXCL1, neutrophil elastase, and CCL11 is shown on a month-to-month basis (B). In A, p values were calculated using Wilcoxon nonparametric tests, in consideration of the limited group-specific sample sizes and the fact that some of the distributions are skewed. In B, p values were calculated using longitudinal mixed-effects models, adjusting for age. IL = interleukin; RRMS = relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; SPMS = secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Myeloid chemokine expression correlates with radiologic lesion burden in SPMS.

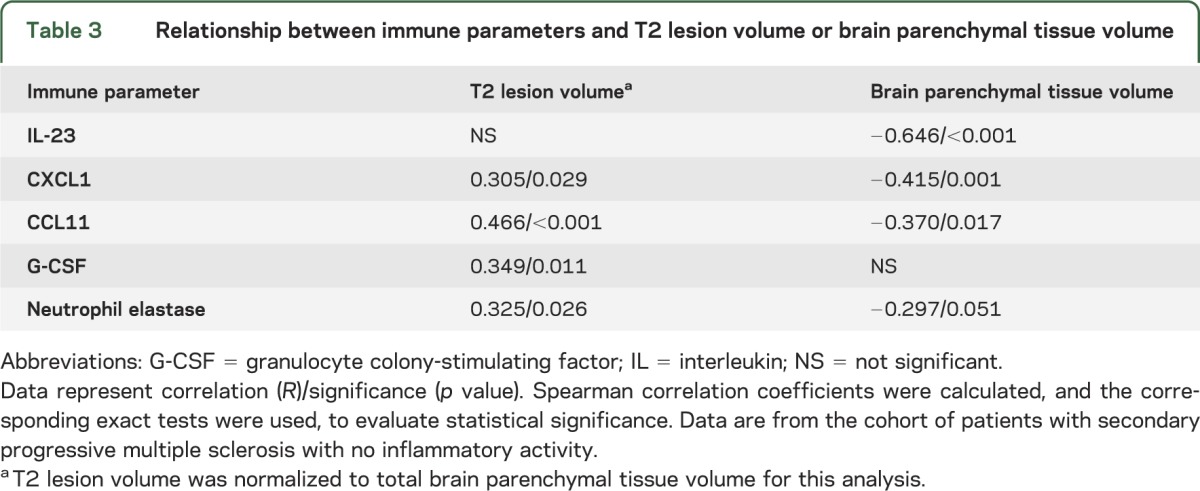

We next investigated the relationship between plasma levels of innate immune molecules and radiologic measures of CNS damage in subjects with SPMS who had no evidence of inflammatory activity over the 1-year observation period. Plasma CXCL1, CCL11, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and neutrophil elastase correlated with normalized T2 lesion volume, a radiologic measure of global tissue damage (table 3). Consistent with this finding, plasma IL-23, CXCL1, CCL11, and neutrophil elastase were negatively associated with total brain parenchymal tissue volume (table 3).

Table 3.

Relationship between immune parameters and T2 lesion volume or brain parenchymal tissue volume

DISCUSSION

A controversial topic in MS is whether accumulation of disability during progressive stages is primarily mediated by an autoimmune or a degenerative process.4 Our findings contribute to a growing body of data indicating that inflammation is still relevant, and associated with CNS damage, in at least some patients with SPMS. We found increased frequencies of circulating MBP-reactive Th1 and Th17 cells in individuals with SPMS, as well as with RRMS, compared with age- and sex-matched HCs. Moldovan et al.,21 studying an independent cohort of patients with RRMS, detected high frequencies of PBMCs producing IFN-γ in response to challenge with libraries of overlapping 9-mer peptides spanning the length of MBP. In contrast, other investigators found no difference in myelin-specific T-cell responses between patients with MS and controls.19,22 These discrepancies could be attributed, at least in part, to technical and methodologic inconsistencies between studies. Hence, discordant results have been obtained when cytokine production and proliferation were used as measures of myelin antigen–specific responses in the same cohort of patients with MS.29 We chose IFN-γ and IL-17 production as our primary outcome measures because of emerging data implicating both Th1 and Th17 cells in MS pathogenesis.30 It has been suggested that IFN-γ/IL-17 double-producing CD4+ T cells are the critical effectors in MS.30,31 We used single-color ELISPOT assays to measure MBP-specific cytokine responses and therefore could not enumerate the frequency of IFN-γ/IL-17 double-producing cells in comparison to single producers.

Recent publications attest to the plasticity of Th17 cells and their propensity to acquire Th1-like properties over time.32,33 Consequently, we anticipated that IFN-γ–producing autoreactive PBMCs would preferentially accumulate, and that IL-17–producing PBMCs would contract, in patients with MS who had longer disease duration. Contrary to our expectations, the mean frequency of MBP-reactive IL-17, but not IFN-γ, producers correlated directly with disease duration. This might be driven by IL-23, the expression of which also increased with disease duration. IL-23 stabilizes Th17 cells, resulting in their preferential accumulation in vivo.34 In support of our results, independent studies have found elevated frequencies of circulating IL-23 receptor+ CD4+ T cells (consistent with Th17 cells) and high serum IL-17 levels in patients with progressive MS compared to patients with RRMS or HCs.35–37 Furthermore, IL-17 messenger RNA and protein have been detected in autopsy brain specimens from patients with progressive MS.38 These findings, in conjunction with our data, are particularly intriguing in light of the discovery of lymphoid-like follicles in the sulci of brain specimens from patients with SPMS, but not RRMS.5 Myelin-reactive Th17 cells induce ectopic follicles in the CNS during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis.39 By extension, increased Th17 frequencies in individuals with SPMS might facilitate the formation of meningeal follicles. It remains to be demonstrated whether differences in the immune response are a cause, or consequence, of the transition from an RR to an SP clinical course. A clinical trial of a monoclonal antibody specific for the IL-12p40 subunit (which neutralizes both IL-12 and IL-23) showed no beneficial effect in RRMS.40 A monoclonal antibody specific for IL-17 is under investigation in RRMS. However, IL-23 and IL-17 neutralizing agents have yet to be assessed as therapeutic agents in progressive MS.

In addition to harboring myelin-reactive Th17 responses, patients with SPMS expressed elevated plasma levels of chemokines and growth factors that activate, mobilize, and recruit myeloid cells. A number of these factors, including CXCL1, CCL11, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, can be induced by IL-17,27,28 providing a hypothetical causative link between their upregulation and enrichment of circulating Th17 cells. Such a pattern of immune dysregulation suggests the existence of a vicious cycle whereby IL-23 produced by activated myeloid cells induces IL-17, and IL-17 induces chemokines and growth factors that mobilize and activate myeloid cells. Our study did not reveal a significant correlation between plasma levels of IL-17 and myeloid-related factors. It is possible that such associations exist, but our study was underpowered to detect them. Alternatively, IL-17 could induce production of innate chemokines and growth factors in a sequestered microenvironment such as the bone marrow and/or CNS, not reflected in plasma expression patterns.

A potential weakness of this exploratory study is its relatively small sample size. This is a reflection, in part, of stringent selection criteria and the extensive resources necessary to rigorously monitor each subject (with serial clinical and radiologic evaluations, as well as immunologic profiles) over the course of 1 year. Despite that limitation, we were able to detect statistically robust correlations between clinical and immune parameters. Our results will need to be validated in independent cohorts of patients with larger sample sizes and a wider diversity of clinical courses and treatment histories. Although we found no statistically significant differences in the levels of immune parameters when comparing untreated patients with RRMS to those treated with glatiramer acetate, the inclusion of the latter group might have contributed to the differences we observed between the RRMS and SPMS cohorts. In addition, we did not observe a significant difference in age between cohorts, but subjects with SPMS had significantly higher EDSS scores and longer disease duration than subjects with RRMS (table 1). Hence, it is possible that expression of IL-17 is more closely associated with degree of disability and/or disease duration than with disease stage. Future studies could be helpful in clarifying these issues.

Pathologic engagement of the innate arm of the immune system, and particularly cells of the myeloid/granulocyte lineage, has previously been recognized as a distinctive feature of SPMS. Other investigators have found enhanced expression of costimulatory molecules and cytokines by peripheral blood monocytes from patients with SPMS compared to those from patients with RRMS or HCs.7–11,26 More recently, it was shown that myeloid dendritic cells isolated from patients with SPMS secrete greater quantities of IL-12 than the same cells from patients with RRMS or HCs.10 Collectively, these data are consistent with our finding of elevated plasma levels of myeloid-related factors in SPMS, and their association with MRI metrics of CNS damage. However, such associations do not definitively demonstrate cause and effect. It is possible that some of the immune abnormalities in SPMS represent an epiphenomenon, or are even part of a counter-regulatory pathway. Furthermore, cytokine profiles in the periphery may differ from, and even oppose, those in the CNS, which might explain the negative correlation between EDSS and proinflammatory mediators such as CCL3 (table 2). To resolve these and related matters, we advocate that further efforts be directed at documenting how the autoimmune response evolves during the course of MS and at identifying stage-specific biomarker, neuropathologic, and therapeutic response profiles. The goal is that such investigations will lead to the development of novel pharmaceutical approaches that ameliorate SPMS, possibly by targeting Th17 cells, myeloid factors, and/or the interactions between them.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- DMA

disease-modifying agent

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- ELISPOT

enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot

- HC

healthy control

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- RRMS

relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

- SP

secondary progressive

- SPMS

secondary progressive multiple sclerosis

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.H. performed immunologic assays and critically reviewed the manuscript. L.W. supervised the statistically analyses, interpreted data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. P.H. performed statistical analyses. X.Z. performed statistical analyses. S.E. supervised MRI studies and critically reviewed the manuscript. A.S. supervised MRI studies and critically reviewed the manuscript. D.I. critically reviewed the manuscript. B.M.S. designed the study, supervised analyses, and wrote the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported by grants from the NIAID, NIH (Autoimmunity Centers of Excellence U19 A1056390, Project 2) (Segal) and the Dana Foundation (Segal) as well as from the David and Donna Garrett Multiple Sclerosis Research Fund.

DISCLOSURE

A. Huber, L. Wang, P. Han, X. Zhang, and S. Ekholm report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. A. Srinivasan is funded by NIH grant R01 NS064973. D. Irani is funded by NIH grants R21 NS074008 and R01 AI089417, and a grant from the Michael J. Fox Foundation. B. Segal has served as a consultant for Novartis and Biogen Idec. He has received investigator-initiated educational grants from Teva Neurosciences and Biogen Idec. He is currently funded by the NIH (grant R01NS057670) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation and Development Service (I01BX001387), and Biomedical Laboratory and Development Service (I01RX000416). Dr. Segal has also received support from the Dana Foundation and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fox EJ, Rhoades RW. New treatments and treatment goals for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol 2012;25(suppl):S11–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panitch H, Miller A, Paty D, Weinshenker B. Interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive MS: results from a 3-year controlled study. Neurology 2004;63:1788–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paolillo A, Coles AJ, Molyneux PD, et al. Quantitative MRI in patients with secondary progressive MS treated with monoclonal antibody Campath 1H. Neurology 1999;53:751–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trapp BD, Nave KA. Multiple sclerosis: an immune or neurodegenerative disorder? Annu Rev Neurosci 2008;31:247–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serafini B, Rosicarelli B, Magliozzi R, Stigliano E, Aloisi F. Detection of ectopic B-cell follicles with germinal centers in the meninges of patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol 2004;14:164–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magliozzi R, Howell O, Vora A, et al. Meningeal B-cell follicles in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis associate with early onset of disease and severe cortical pathology. Brain 2007;130:1089–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaknin-Dembinsky A, Weiner HL. Relationship of immunologic abnormalities and disease stage in multiple sclerosis: implications for therapy. J Neurol Sci 2007;259:90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filion LG, Matusevicius D, Graziani-Bowering GM, Kumar A, Freedman MS. Monocyte-derived IL12, CD86 (B7-2) and CD40L expression in relapsing and progressive multiple sclerosis. Clin Immunol 2003;106:127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karni A, Koldzic DN, Bharanidharan P, Khoury SJ, Weiner HL. IL-18 is linked to raised IFN-gamma in multiple sclerosis and is induced by activated CD4(+) T cells via CD40-CD40 ligand interactions. J Neuroimmunol 2002;125:134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karni A, Abraham M, Monsonego A, et al. Innate immunity in multiple sclerosis: myeloid dendritic cells in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis are activated and drive a proinflammatory immune response. J Immunol 2006;177:4196–4202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner HL. A shift from adaptive to innate immunity: a potential mechanism of disease progression in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2008;255(suppl 1):3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kutzelnigg A, Lucchinetti CF, Stadelmann C, et al. Cortical demyelination and diffuse white matter injury in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2005;128:2705–2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frischer JM, Bramow S, Dal-Bianco A, et al. The relation between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brains. Brain 2009;132:1175–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashton EA, Takahashi C, Berg MJ, Goodman A, Totterman S, Ekholm S. Accuracy and reproducibility of manual and semiautomated quantification of MS lesions by MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2003;17:300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashton EA, Parker KJ, Berg MJ, Chen CW. A novel volumetric feature extraction technique with applications to MR images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 1997;16:365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman EB, Sen PK, Weinberg CR. Within-cluster resampling. Biometrics 2001;88:1121–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieger RH, Weinberg CR. Analysis of clustered binary outcomes using within-cluster paired resampling. Biometrics 2002;58:332–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grau-López L, Raïch D, Ramo-Tello C, et al. Myelin peptides in multiple sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev 2009;8:650–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Rosbo NK, Ben-Nun A. T-cell responses to myelin antigens in multiple sclerosis: relevance of the predominant autoimmune reactivity to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. J Autoimmun 1998;11:287–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moldovan IR, Rudick RA, Cotleur AC, et al. Interferon gamma responses to myelin peptides in multiple sclerosis correlate with a new clinical measure of disease progression. J Neuroimmunol 2003;141:132–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diaz-Villoslada P, Shih A, Shao L, Genain CP, Hauser SL. Autoreactivity to myelin antigens: myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein is a prevalent autoantigen. J Neuroimmunol 1999;99:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bielekova B, Sung MH, Kadom N, Simon R, McFarland H, Martin R. Expansion and functional relevance of high-avidity myelin-specific CD4+ T cells in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 2004;172:3893–3904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke MA, Carlson TJ, Andjelkovic AV, Segal BM. IL-12- and IL-23-modulated T cells induce distinct types of EAE based on histology, CNS chemokine profile, and response to cytokine inhibition. J Exp Med 2008;205:1535–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balashov KE, Comabella M, Ohashi T, Khoury SJ, Weiner HL. Defective regulation of IFNgamma and IL-12 by endogenous IL-10 in progressive MS. Neurology 2000;55:192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balashov KE, Smith DR, Khoury SJ, Hafler DA, Weiner HL. Increased interleukin 12 production in progressive multiple sclerosis: induction by activated CD4+ T cells via CD40 ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997;94:599–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saleh A, Shan L, Halayko AJ, Kung S, Gounni AS. Critical role for STAT3 in IL-17A-mediated CCL11 expression in human airway smooth muscle cells. J Immunol 2009;182:3357–3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onishi RM, Gaffen SL. Interleukin-17 and its target genes: mechanisms of interleukin-17 function in disease. Immunology 2010;129:311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venken K, Hellings N, Hensen K, Rummens JL, Stinissen P. Memory CD4+CD127high T cells from patients with multiple sclerosis produce IL-17 in response to myelin antigens. J Neuroimmunol 2010;226:185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kebir H, Ifergan I, Alvarez JI, et al. Preferential recruitment of interferon-gamma-expressing TH17 cells in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2009;66:390–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duhen R, Glatigny S, Arbelaez CA, Blair TC, Oukka M, Bettelli E. Cutting edge: the pathogenicity of IFN-gamma-producing Th17 cells is independent of T-bet. J Immunol 2013;190:4478–4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirota K, Duarte JH, Veldhoen M, et al. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol 2011;12:255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee YK, Turner H, Maynard CL, et al. Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity 2009;30:92–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haines CJ, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, et al. Autoimmune memory T helper 17 cell function and expansion are dependent on interleukin-23. Cell Rep 2013;3:1378–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christensen JR, Börnsen L, Ratzer R, et al. Systemic inflammation in progressive multiple sclerosis involves follicular T-helper, Th17- and activated B-cells and correlates with progression. PLoS One 2013;8:e57820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Esendagli G, Kurne AT, Sayat G, Kilic AK, Guc D, Karabudak R. Evaluation of Th17-related cytokines and receptors in multiple sclerosis patients under interferon β-1 therapy. J Neuroimmunol 2013;255:81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saresella M, Piancone F, Tortorella P, et al. T helper-17 activation dominates the immunologic milieu of both amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and progressive multiple sclerosis. Clin Immunol 2013;148:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lock C, Hermans G, Pedotti R, et al. Gene-microarray analysis of multiple sclerosis lesions yields new targets validated in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Med 2002;8:500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peters A, Pitcher LA, Sullivan JM, et al. Th17 cells induce ectopic lymphoid follicles in central nervous system tissue inflammation. Immunity 2011;35:986–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segal BM, Constantinescu CS, Raychaudhuri A, et al. Repeated subcutaneous injections of IL12/23 p40 neutralising antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, dose-ranging study. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.