Abstract

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is an exceedingly rare hematologic malignancy that typically presents in the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and lymph nodes. Few cases of HS have been reported in the head and neck. We describe the case of a two-year-old girl presenting with two weeks of left lower eyelid swelling. Diagnostic testing and biopsy revealed a large inferior orbital mass causing severe bony destruction with extension into the sinuses. Pathologic analysis revealed classic features of histiocytic sarcoma. To the best of our knowledge, no previous case of histiocytic sarcoma occurring in the orbit of a child has been reported. We present an exceedingly rare case of histiocytic sarcoma in a young child presenting with eyelid swelling.

Case Report

A two-year-old Caucasian female with no significant past medical history presented to an outside hospital with left eyelid swelling after a fall. The patient was treated with antibiotic drops without improvement. Over the ensuing two weeks, the patient continued to have eyelid swelling which did not respond to further treatment with oral and topical antibiotics. The patient was then seen by an ophthalmologist at a second institution who was concerned for an orbital process and ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the orbits with contrast. The scan showed a heterogeneous, inferiorly based orbital mass that demonstrated extensive bony erosion into the maxillary sinus and zygoma (Figure 1). A CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not reveal masses elsewhere in the body. In addition, a whole body bone scan showed increased activity in left maxillary and zygomatic bone without evidence of metastatic disease.

Figure 1.

CT orbits with contrast. A. Axial sections showing inferior based orbital mass causing hyperglobus. B. Sagittal sections showing extent of zygoma destruction. C, D. Coronal sections showing heterogeneous features and extension into the facial soft tissue and body of the zygoma.

The patient was transferred to our institution for urgent biopsy of the mass. On examination, the patient was able to fix and follow with each eye, no afferent pupillary defect was noted, mild resistance to retropulsion was detected, and there was minimal gross proptosis. There was no restriction with extraocular motility or strabismus seen. There was a palpable mass in the anterior, inferior orbit with extension into the soft tissues of the cheek. Furthermore, the left globe was displaced superiorly. On slit lamp examination, there was neither chemosis nor conjunctival injection. The anterior and posterior segment examinations were normal.

After a thorough discussion with the child’s parents, an incisional biopsy via a transconjunctival anterior orbitotomy and a concurrent bone marrow biopsy were performed. Intraoperatively, the lesion appeared reddish blue and there was extensive bony destruction of the zygoma and orbital floor (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Intraoperative photos. A. External preoperative photo showing lack of ocular inflammatory findings and mild lower lid induration. B. Photo of inferior orbital mass.

Pathologic analysis of the lesion demonstrated a diffusely infiltrating, hypercellular tumor without architectural features. Polymorphic lesional cells with granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei that were primarily round or oval and contained prominent nucleoli were seen with hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rare osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells were also noted. There was minimal mitotic activity and no necrosis. Additionally, a moderately intense inflammatory reaction was seen. Immunohistochemistry and cytochemistry were performed. Initial bone marrow sampling revealed no infiltration with tumor and 2% blasts, which could represent benign immature hematopoietic elements. However bone marrow core biopsy was inadequate to definitively identify these cells. A subsequent biopsy was negative for morphologic evidence of tumor in the bone marrow (Figure 3).

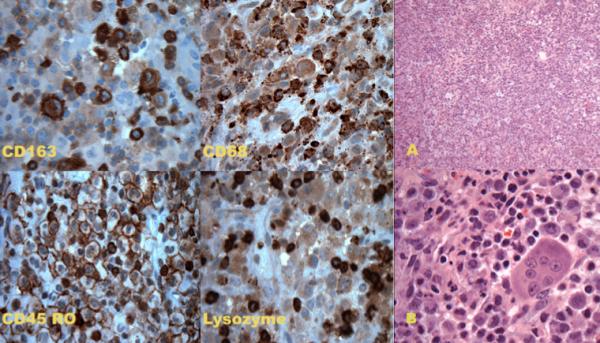

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry and cytochemistry images showing positive staining with CD163, CD68, CD45 and lysozyme. Hematoxylin and Eosin images. A. Low power (10×) showing diffuse, hypercellular lesion without architectural features. B. High power (60×) showing lesional cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, large nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cell is also noted as is inflammatory background with rare eosinophils.

A diagnosis of histiocytic sarcoma was made. Pediatric hematology and oncology initiated chemotherapy treatment using the AEIOP anaplastic large cell lymphoma protocol 99. Thirteen months after presentation the patient is tumor free without evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

Histiocytic sarcoma is a rare and aggressive neoplasm defined by the World Heath Organization as “malignant proliferation of cells showing morphologic and immunophenotypic features of mature tissue histiocytes.1” It represents less than 1% of all hematologic non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas.2 Prior reports in the older literature using this term likely represented diffuse large b-cell lymphoma or anaplastic large cell lymphoma. 3 HS most commonly presents in the lymph nodes, bone marrow, intestines, skin, and spleen.3 Only a few cases of HS presenting in the head and neck region have been described including the, palate2, nasal cavity3, parotid gland4, zygomatic, preauricular region5, and forehead.6 To our knowledge, there are no reports of HS occurring in the orbit of a child.

The pathologic features of histiocytic sarcoma may include pleomorphic lesional cells with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, large oval or round nuclei with prominent nucleoli, and occasional infolding of nuclei.3,4 Immunohistochemistry and cytochemistry typically reveal lysozyme positive, vimentin positive, CD4, CD45, CD68, and CD163 positive cells that are negative for other T and B cell markers, langerin, CD1a, myeloperoxidase, and epithelial markers. Focal S100 positivity has been noted in some studies.1,5,7,8 All of these features, with the exception of focal positivity with S100 were noted in our patient.

Prognosis of HS is typically poor as it often presents as disseminated disease and there is no consensus on management. Various authors have suggested treatment with local resection and adjuvant radiation, while others have treated with myeloid leukemia, anaplastic lymphoma protocols or even thalidomide.3,9 Hornick et al demonstrated there have been significant rates of local and distant recurrences reported after local excision.3 Similarly, chemotherapy has shown poor results.10,11 In the series described by Pileri et al, there were three children whose disease progressed despite chemotherapy.12

We report an exceedingly rare case of HS in a young patient with an extremely unusual presentation of ophthalmic findings only without systemic disease. Following chemotherapy using the AEIOP anaplastic large cell lymphoma protocol 99, the patient is disease free 13 months after her last cycle of chemotherapy.

Conclusion

Histiocytic sarcoma is an extremely rare malignancy with a poor prognosis. Suspicion for this lesion in patients with orbital masses may help with early diagnosis and initiation of care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Dr. Mehendale for pathology slides and analysis.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: Supported by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness. New York, NY Dr. Vinay K Aakalu is supported by NEI/NIH K12 Clinical Scientist Training Grant, Bethesda, MD

Footnotes

PROPRIETARY INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report no conflicting financial interests.

MEETING PRESENTATION:

These data have been presented at the Southeastern Ocular Oncology and Pathology Conference. Atlanta, GA September 30, 2011

HIPAA STATEMENT

In addition, this case report is in compliance with HIPAA regulations.

References

- 1.Jaffe R, Pileri SA, Facchetti F, et al. Histiocytic and dendritic neoplasms. In: Swerdlow SH, et al., editors. WHO Classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: 2008. pp. 354–367. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vos JA, Abbondanzo SL, Barekman CL, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma: a study of five cases including the histiocyte marker CD163. Modern Pathology. 2005;18:693–704. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornick JL, Jaffe ES, Fletcher C. Extranodal histiocytic sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 14 cases of a rare epithelioid malignancy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1133–44. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000131541.95394.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akiba J, Harada H, Kawahara A, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma of the parotid gland region. Pathol Int. 2011 Jun;61(6):373–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02671.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02671.x. Epub 2011 May 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexiev BA, Sailey CJ, McClure SA, et al. Primary histiocytic sarcoma arising in the head and neck with predominant spindle cell component. Diagn Pathol. 2007 Feb;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnettler K, Salomone C, Valbuena JR. Cutaneous histiocytic sarcoma: report of one case. Rev Med Chil. 2009 Apr;137(4):547–51. Doi:/S0034-98872009000400014. Epub 2009 Jun 25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell S, Hanzely Z, Alakandy LM, et al. Primary meningeal histiocytic sarcoma: a report of two unusual cases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011 Jun 29; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01205.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devic P, Androdias-Condemine G, Streichenberger N, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma of the central nervous system: a challenging diagnosis. QJM. 2010 Dec 24; doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq244. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq244. Epub 2010 Dec 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gergis U, Dax H, Ritchie E, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in combination with thalidomide as treatment for histiocytic sarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Apr 1;29(10):e251–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.6603. doi: 10.1200/jco.2010.32.6603. Epub 2011 Jan 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauritzen AF, Delsol G, Hansen NE, et al. Histiocytic sarcomas and monoblastic leukemias. A clinical, histologic, and immunophenotypical study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:45–54. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/102.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ralfkiaer E, Delsol G, O’Connor NTJ, et al. Malignant lymphomas of true histiocytic origin. A clinical, histological, immunophenotypic and genotypic study. J Pathol. 1990;160:9–17. doi: 10.1002/path.1711600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pileri SA, Grogan TM, Harris NL, et al. Tumours of histiocytes and accessory dendritic cells: an immunohistochemical approach to classification from the International Lymphoma Study Group based on 61 cases. Histopathology. 2002 Jul;41(1):1–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]