Abstract

The current study examined differences in emotion expression identification between adolescents characterized with behavioral inhibition (BI) in childhood with and without a lifetime history of anxiety disorder. Participants were originally assessed for behavioral inhibition during toddlerhood and for social reticence during childhood. During adolescence, participants returned to the laboratory and completed a facial-emotion identification task and a clinical psychiatric interview. Results revealed that behaviorally inhibited adolescents with a lifetime history of anxiety disorder displayed a lower threshold for identifying fear relative to anger emotion expressions compared to non-anxious behaviorally inhibited adolescents and non-inhibited adolescents with or without anxiety. These findings were specific to behaviorally inhibited adolescents with a lifetime history of social anxiety disorder. Thus, adolescents with a history of both BI and anxiety, specifically social anxiety, are more likely to differ from other adolescents in their identification of fearful facial expressions. This offers further evidence that perturbations in the processing of emotional stimuli may underlie the etiology of anxiety disorders.

Cognitive models of anxiety suggest that information-processing biases, particularly negative biases, are central to the etiology and maintenance of anxiety disorders (Clark & Wells, 1995). Specifically, compared to non-anxious individuals, anxious individuals display biases in a range of information-processing functions including a greater likelihood of allocating their attention to threatening stimuli (Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2007), remembering threatening words (Coles & Heimberg, 2002), and interpreting ambiguous stimuli as threatening (Richards, 2004). A number of studies examining these biases rely on face-viewing tasks. This generates interest in the manner in which face emotions bias information processing.

Across many cultures, humans show similar capacities to display and recognize a range of face emotions (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002). Moreover, these capacities unfold in a predictable fashion during development, where the capacity to identify some emotions consistently arises earlier than other emotions (Herba & Phillips, 2004). Finally, brain imaging research suggests that this unfolding reflects core features of brain development (Taylor, Batty, & Itier, 2004). When combined with research on face-emotion information-processing biases, this research on face-emotion labeling generates key questions, concerning the relationship between face-emotion labeling and anxiety. Interestingly, considerable research examines the relation between face-emotion-labeling ability and anxiety (Easter et al., 2005; Melfsen & Florin, 2002; Simonian, Beidel, Turner, Berkes, & Long, 2001; Veljaca & Rapee, 1998). However, relatively few studies examine the association with anxiety in a pediatric population, and no longitudinal work considers the manner in which such associations unfold across development. To address these concerns, the current study examines the manner in which clinical and temperamental variations in anxiety interact to predict face-emotion-labeling ability in adolescence.

Behavioral inhibition (BI), a temperament identified during early childhood, is characterized by the tendency to display hypervigilance and avoidance to novelty (Fox, Henderson, Rubin, Calkins, & Schmidt, 2001). Children high and stable in BI through early childhood are at heightened risk for developing anxiety disorders, particularly social anxiety disorder (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Schwartz, Snidman, & Kagan, 1999). Adolescents characterized with BI as children display increased attention to novelty (Reeb-Sutherland, Vanderwert, et al., 2009), heightened attention bias to threat (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2010; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011), and elevated startle responses (Reeb-Sutherland, Helfinstein, et al., 2009). This observed bias toward looking for threat and novelty in children with BI may lead to an increase in anxious behaviors (Fox, Hane, & Pine, 2007). However, not all behaviorally inhibited children develop anxiety. Therefore, it is important to identify additional behavioral markers that may be used to differentiate between behaviorally inhibited children who develop anxiety and those who do not. One such marker may be behaviorally inhibited children’s bias in identifying social threats, particularly when presented in the form of emotional facial expressions.

The few available studies on facial-affect processing in behaviorally inhibited children have focused primarily on threat-related attention processes. For example, behaviorally inhibited children (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011) and adolescents (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2010) display increased attention bias to facial displays of anger which, in turn, relates to increased social withdrawal. This work focuses on capturing implicit or more automatic face processing biases (Mogg & Bradley, 1998); however, they do not address how behaviorally inhibited children may differ in explicit face processing compared to non-inhibited children. Because one must first recognize the emotional expressions on faces in order to differentially direct attention to one emotional expression compared to another, it is also important to identify differences that may exist between behaviorally inhibited and non-inhibited children in their explicit evaluative biases. To examine this possibility, using a well-described facial emotion morphing task (Pollak & Kistler, 2002), the current study examined whether identification of facial affect would differentiate adolescents characterized in childhood with BI who may or may not have a lifetime history of anxiety disorder. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that has examined emotional facial identification in behaviorally inhibited children with and without anxiety. Previous research found that behaviorally inhibited children showed greater levels of social withdrawal only if they also displayed increased attention bias to threat (i.e., angry faces; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2010; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011); therefore, we predicted that behaviorally inhibited children with a history of anxiety, specifically social anxiety, will display a lower threshold for identifying angry faces compared to adolescents without a history of BI and anxiety.

Method

Participants

Adolescents were recruited from two cohorts of 165 Caucasian children (81 male) participating in an ongoing longitudinal study of temperament and emotional reactivity (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Fox et al., 2001). The original cohorts were selected at 4 months of age based on their positive and negative affect and motor reactivity to novel auditory and visual stimuli (Fox et al., 2001). In adolescence, participants from the original sample (N=113; 56 male) returned to the laboratory for the current study. Six children were excluded from the current analyses because they did not finish or were not attending to the task. An additional 4 children were excluded because diagnostic assessment of anxiety was not obtained. The final sample consisted of 103 adolescents (M=15.06 years, SD=.96 years, n=53 male). No differences in age, sex, or childhood temperament were found between adolescents who participated and those who did not (n=62).

The University of Maryland institutional review board approved the current study. All adolescents and their parents provided written assent/consent prior to participation in the current study.

Measures

BI profiles

BI was assessed at 14 and 24 months of age and social reticence was assessed at 4 and 7 years of age using standard laboratory procedures previously described elsewhere (Fox et al., 2001; also see Supplemental Methods). Longitudinal profiles of BI were obtained by performing a latent class analysis (LCA), a subtype of structural equation mixture modeling (SEMM), on behavioral composites of BI at 14 and 24 months and social reticence at 4 and 7 years. Due to the skewness of the data, behavioral measures were individually dichotomized where 0 denoted a child rated in the lower half of the sample at a particular time point and 1 denoted a child rated in the top half of the sample at that time point. The 2-profile model was found to be the best fitting model compared to a 1-, 3-, or 4-profile model. Forty-one percent of the sample displayed high average levels of BI at all four time points and had a greater probability of belonging to this “high” BI profile (High BI, n=42, 19 males). In contrast, the remaining 59% of the sample showed low average levels of BI across the four time points and had a greater probability of belonging to this “low” BI profile (Low BI, n=61, 34 males). These profiles have previously been used to examine the moderating role of the potentiated startle reflex (Reeb-Sutherland, Helfinstein, et al., 2009) and neural responses to novelty (Reeb-Sutherland, Vanderwert, et al., 2009) in the relation between BI and anxiety. For additional details regarding the BI profiles and benefits of using such analyses, see Supplemental Methods.

Facial identification task

The current study used morphed facial images previously described (Pollak & Kistler, 2002) to examine emotion identification biases. Stimuli consisted of greyscale images of morphed blends of four emotion prototypes (fear, happiness, anger, and sadness). Four continua were examined in the current study: Angry-Fear, Angry-Sad, Fear-Happy, and Happy-Sad. Each continuum of 11 images began with one prototypical expression (e.g., 100% Happy) and ended with a second prototypical expression (e.g., 100% Angry) differing by 10% pixel intensities from one prototypical expression to the other. Two sets of stimuli, one male and one female, were presented for each continuum. The number of presentations for each blended image varied depending upon the ambiguity of the emotion presented. Specifically, 70–100% blends were considered less ambiguous (e.g., 80% Happy and 20% Angry) and were presented four times (2 male images, 2 female images) while 40–60% blends were considered more ambiguous (e.g., 60% Happy and 40% Angry) and were presented for a total of eight presentations (4 male images, 4 female images). We presented each morphed facial image with the labels for the two emotions used to create the morph. Participants then pressed a button indicating which emotion label they thought best described the facial image. Adolescents completed a total of 224 trials across the four continua. See Supplemental Methods for more task details and benefits of using this specific task.

Diagnostic interview for psychiatric problems

Adolescents and their parents (most often mothers) were separately administered the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children – Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, & Rao, 1997)), a semi-structured diagnostic interview assessing DSM-IV disorders. Interviews were conducted by advanced clinical psychology doctoral students under the close supervision of a licensed clinical psychologist and a board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrist, all of whom were blind to early temperament data (see Supplemental Methods for more details). The current study focused on the lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders that included separation anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, simple phobia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (see Supplemental Table 1 for a breakdown of diagnosis among the High and Low BI adolescents). There were 13 High BI (M=15.00 years, SD=.96 years, n=6 males) adolescents with a history of anxiety diagnosis and 29 High BI (M=14.89 years, SD=1.01 years, n=13 males) adolescents without a history of anxiety. Among the Low BI participants, 19 (M=15.13 years, SD=1.04 years, n=11 males) had a history of anxiety and 42 (M=15.16 years, SD=.90 years, n=23 males) did not. All adolescents with a lifetime occurrence of anxiety had a past diagnosis of an anxiety disorder and 21 adolescents (13 Low BI, 8 High BI) had a current diagnosis of anxiety at the time of assessment. Further details about the prevalence and history of anxiety disorders in this sample have been reported elsewhere (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009).

Data analyses

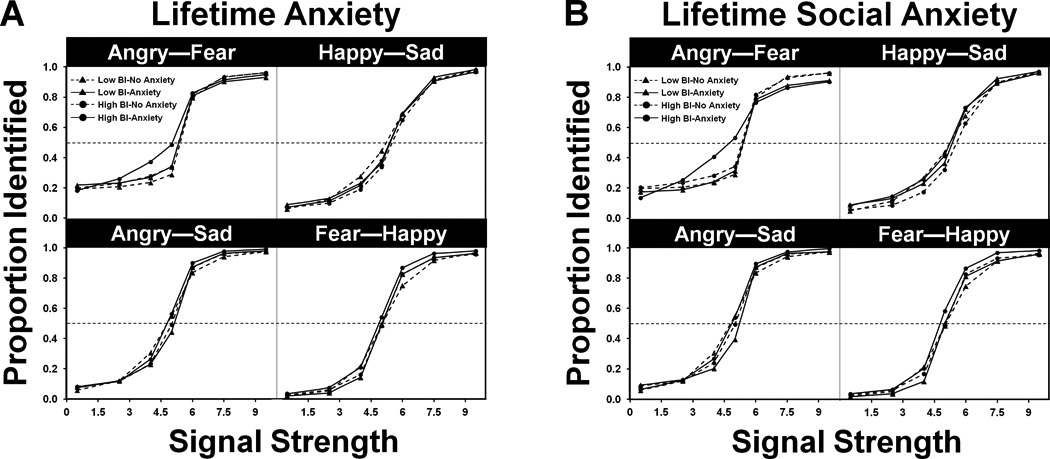

Individual performance on the facial identification task was determined by fitting logistic functions for each continuum using the formula suggested by Pollak and Kistler (2002): P(identification)=c+(d–c)/(1+e−(x – a)/b) where x is signal strength and P is the probability of identification. Four parameters were estimated: a is the function midpoint, 1/b is the slope, and c and d represent the lower and upper asymptotes, respectively. The category boundary mean is estimated by computing the signal value that corresponds to the probability of identification being chance or .5 (P = .5) and reflects the perceptual threshold at which the two emotions in the continua are equally likely to be identified. Data from adjacent categories of less ambiguous faces were grouped together. Category boundary means and standard errors are presented in Table 1 and the observed data and fitted functions are plotted for each group in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Perceptual threshold estimates (standard error) for behaviorally inhibited (High BI) and non-inhibited (Low BI) adolescents with and without a lifetime occurrence of having an anxiety and social anxiety disorders.

| Category | Low BI | High BI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Anxiety | Anxiety | No Anxiety | Anxiety | |

| Angry—Fear | 5.66 (.13)a | 5.72 (.19)b | 5.43 (.16)c | 4.68 (.23)abc |

| Angry—Sad | 4.75 (.09) | 4.91 (.13) | 4.91 (.11) | 4.72 (.16) |

| Fear—Happy | 5.10 (.10) | 5.08 (.15) | 4.97 (.12) | 4.80 (.18) |

| Happy—Sad | 5.13 (.12) | 5.36 (.17) | 5.55 (.14) | 5.40 (.21) |

| No Social Anxiety | Social Anxiety | No Social Anxiety | Social Anxiety | |

| Angry—Fear | 5.65 (.13)a | 5.80 (.24)b | 5.44 (.16)c | 4.09 (.34)abc |

| Angry—Sad | 4.75 (.09) | 5.01 (.17) | 4.91 (.1) | 4.66 (.24) |

| Fear—Happy | 5.09 (.10) | 5.13 (.20) | 4.97 (.12) | 4.82 (.27) |

| Happy—Sad | 5.13 (.12) | 5.33 (.22) | 5.55 (.14) | 5.21 (.31) |

p<.05,

p<.05,

p<.10

Note. Data for each continuum were modeled by fitting a logistic function in order to estimate four parameters: signal threshold (e.g., category boundary), slope, and lower and upper asymptotes for each individual subject. The parameter of interest is the perceptual threshold estimate which is the point at which the signal strength value corresponds to a probability (P) of identification at P = 0.5. High BI adolescents with a lifetime occurrence of anxiety differed in their threshold estimates compared to the other groups only on the Angry—Fear continuum. The lower threshold in the High BI adolescents with anxiety compared to the other groups suggests an overidentification of fear compared to anger.

Figure 1.

Results from the emotion identification task for each emotion pair for behaviorally inhibited (High BI) and non-inhibited (Low BI) adolescents with and without a lifetime history of anxiety (A) and social anxiety (B). Proportion identified (y-axis) indicates the proportion of trials in which responses matched the identity of the second emotion in the pair relative to the first emotion in the pair (e.g., for the Angry—Fear pair: signal strength (x-axis) of 1 = 90% Angry/ 10% Fear whereas signal strength of 9 = 10% Angry/90% Fear). Low BI adolescents are indicated with triangles and High BI adolescents are indicated with circles. Adolescents with a history of anxiety (A) or social anxiety (B) are plotted in solid lines and adolescents with no history of anxiety are plotted in dashed lines. Data show a clear change in identity judgments as a function of changes in stimulus intensity for all four emotion continua. However, High BI children with a history of anxiety (A) or social anxiety (B) over-identify fear relative anger compared to Low BI children with or without anxiety and High BI children without anxiety.

Cross correlations were conducted on the category boundary estimates to determine if strong relations existed among the four continua. Because no strong relations were found, separate univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the category boundary estimates for each of the four continua to examine the effects of temperament (High BI, Low BI) and lifetime diagnosis of anxiety (Anxiety, No Anxiety). Planned comparison t-tests were conducted only if a significant interaction effect was found. Due to unequal group sizes, Scheffé’s correction was used to adjust p-values for follow-up comparisons. Corrected p-values are reported for all follow-up tests. In addition, if there was a violation in the assumption of homogeneity of variance, then follow-up t-values and dfs were adjusted using the Welch-Satterthwaite method.

Previous studies examining BI as a risk marker for anxiety have shown that behaviorally inhibited children and adolescents are at particular risk for social anxiety (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Schwartz et al., 1999). Therefore, analyses were conducted to examine the specific effect of being both behaviorally inhibited and having a history of social anxiety on emotion identification. Univariate ANOVA and follow-up t-tests were conducted as previously described, but excluded all adolescents who do not have a history of social anxiety; therefore, the total sample is smaller (N=88; BI with social anxiety: N=6, low BI-social anxiety: N=12).

Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether adolescent males and females differed on dependent or independent measures. No significant sex effects were found for BI or anxiety diagnosis, ps>.20. However, a significant sex effect on emotion identification in the Fear-Happy, F(1,101)=4.31, p<.05, ƞ2=.04, and Happy-Sad, F(1,101)=5.54, p=.02, ƞ2=.05, continua was found. Specifically, compared to females, males had a lower threshold for identifying happiness when blended with fear or sadness. Because we were specifically interested in the interaction between BI and anxiety diagnosis, all subsequent analyses included sex as a covariate.

Results

Figure 1A displays the four different emotion continua for High and Low BI adolescents with and without a history of anxiety disorders. High BI adolescents with anxiety showed a clear shift in identification of emotional expression in the Angry-Fear continuum compared to the other three groups (see Figure 1A-top left). A significant temperament × anxiety interaction effect was found only for the Angry-Fear continuum, F(1,98)=5.12, p<.05, η2=.05. Specifically, the estimated category boundary for the High BI adolescents with anxiety was lower than predicted while the other groups’ category boundary estimates were higher than predicted (see Table 1). This suggests that anxious High BI adolescents had a lower threshold to identify facial expressions of fear relative to anger, while the other groups had a higher threshold for fear relative to anger.

Follow-up t-tests revealed that High BI adolescents with a lifetime occurrence of anxiety disorders has a significantly lower category boundary estimate on the Angry-Fear continuum compared to Low BI adolescents with, t(15.18)=2.69, p<.05, d=1.38, and without, t(13.54)=2.61, p<.01, d=1.42, anxiety. In addition, there was a trend for High BI adolescents with anxiety to have a lower category boundary estimate for fear relative to anger, compared to High BI adolescents without anxiety, t(18.42)=1.86, p<.10, d=.87. For the Happy-Sad, Happy-Fear, and Angry-Sad continua, category boundaries were near the midpoint of the continua for all groups and no significant interaction or main effects were found (Angry-Sad: F(1,98) = 1.96, p=.16, Happy-Sad: F(1,98)=1.37, p>.20, and Fear-Happy: F(1,98)=.31, p>.20). Similar analyses were conducted to examine whether having a current diagnosis of anxiety produced similar findings, but no significant main or interaction effects were found, ps>.20.

When the specific effect of having a history of social anxiety was examined, a significant temperament by social anxiety interaction effect also emerged, once again only for the Angry-Fear continuum, F(1,84)=10.40, p<.01, η2=.110 (see Figure 1B). Specifically, the estimated category boundary for the High BI adolescent with social anxiety was lower than predicted while the other groups’ category boundary estimates were higher than predicted (see Table 1), suggesting that socially-anxious High BI adolescents over-identified fear relative to angry faces, while the other groups under-identified fear relative to anger.

Follow-up t-tests revealed that High BI adolescents with a lifetime occurrence of social anxiety disorder displayed a lower category boundary estimate on the Angry-Fear continuum compared to High BI adolescents without social anxiety, t(5.90)=2.07, p<.05, d=1.70, and Low BI adolescents with, t(5.92)=2.63, p<.05, d=2.16, and without, t(5.22)=2.48, p<.05, d=2.18, social anxiety. Category boundaries were near the midpoint of the continua for all the groups for the Happy-Sad, Happy-Fear, and Angry-Sad continua and no significant interaction or main effects were found (Angry-Sad: F(1,84) = 2.31, p=.13, Happy-Sad: F(1,84)=1.67, p>.20, and Fear-Happy: F(1,84)=.23, p>.20). Having a current diagnosis of social anxiety did not significantly affect emotion identification, ps>.20. Moreover, when adolescents with social anxiety were excluded and adolescents with a history of others types of anxiety were included in the analyses, a significant interaction effect was no longer present, F(1, 80)=.175, p=.68), further suggesting that social anxiety may be leading to the observed effects.

Discussion

In this study we found that behaviorally inhibited adolescents who had a history of anxiety disorders identified fear relative to anger earlier in the morphing process than their peers. This association appeared to arise specifically amongst adolescents with a history of social anxiety disorder. These results suggest that behaviorally inhibited adolescents with a history of anxiety, particularly social anxiety, may have a greater sensitivity for fear and may therefore classify a broader range of negative emotions as indicating the presence of fear.

Behaviorally inhibited children (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2010; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011) display increased attention bias toward angry versus neutral faces. Given these findings, we predicted that behaviorally inhibited adolescents would display a lower threshold for the identification of angry faces compared to other emotions. In contrast, we found an over-identification of fear relative to angry faces among behaviorally inhibited adolescents with a history of anxiety. This over-identification of fear may be attributed to differences in the presentation timing and attention allocation to the stimuli. Previous reports found that a threat bias in behaviorally inhibited versus non-inhibited adolescents only existed when facial stimuli were presented for a brief (i.e., 500 ms) rather than longer (i.e., 1500 ms) period of time (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2010). In addition, studies that examined threat bias in behaviorally inhibited (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2010; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011) and anxious children (Roy et al., 2008) did not require participants to explicitly attend to the face stimuli. In contrast, participants had unlimited time to respond and were required to directly attend to the face prior to emotion identification. This suggests that differences in the evaluation of social threats between behaviorally inhibited and non-inhibited adolescents may be more apparent when implicit or automatic types of evaluative bias are examined (Mogg & Bradley, 1998).

Behaviorally inhibited adolescents with a history of anxiety did not show a lower threshold for identifying fear in the Fear-Happy continuum, suggesting that their over-identification of fear is evident only within the context of the Angry-Fear continuum. Given that children are more accurate at identifying and labeling happy faces compared to other emotions (Guyer et al., 2007) even when briefly presented (Silvia, Allan, Beauchamp, Maschauer, & Workman, 2006), it may be that the continua containing happy faces are less ambiguous than those containing other emotion expressions, particularly pairs of negative expressions. Within the context of these highly ambiguous situations, behaviorally inhibited adolescents with anxiety may be biased to select fear compared to other negative emotions. Given the limited number of continua in the current study, the Anger-Fear continuum may have been the only condition that contained sufficient ambiguity to reveal this biased response. Future studies should examine fear and anger in relation to other negative emotions (i.e., disgust, sadness) in order to further investigate other potential ambiguous conditions.

High BI adolescents with social anxiety, excluding other types of anxiety, displayed a lower threshold for identifying fear relative to anger compared to the other adolescent groups. When other types of anxiety were examined (while excluding social anxiety), these effects were no longer significant. This suggests that the observed effects may be specific to having a history of both childhood BI and social anxiety. These results are in line with other studies that have reported aberrant processing of fearful facial expressions in individuals diagnosed with social anxiety (Garner, Baldwin, Bradley, & Mogg, 2009) or are characterized as being high in trait social anxiety (Richards et al., 2002). Individuals with social anxiety, when faced with ambiguous social situations, may respond by envisioning themselves as experiencing fear (Clark & Wells, 1995). This bias in cognition may then be reflected in the increased sensitivity to fearful faces observed in the current study.

A lower threshold to identify fear versus anger distinguished behaviorally inhibited adolescents with a history of childhood anxiety from non-inhibited adolescents with a similar history of anxiety. Previous studies examining identification of facial expressions in both adults and children with anxiety disorders have been inconsistent. Some studies reported that individuals with anxiety either display a general deficit in identifying emotional expressions by labeling neutral facial expressions as negative (Easter et al., 2005; Melfsen & Florin, 2002; Simonian et al., 2001; Veljaca & Rapee, 1998) while other studies reported more specific deficits in the labeling of angry (Battaglia et al., 2004; Jarros et al., 2012), fearful (Garner et al., 2009; Richards et al., 2002), or happy (Silvia et al., 2006) facial expressions. As well, some studies reported finding no differences emotion identification between anxious and non-anxious individuals (Cooper, Rowe, & Penton-Voak, 2008; Guyer et al., 2007; McClure, Pope, Hoberman, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2003; Schofield, Coles, & Gibb, 2007). In the current study, not all adolescents with a history of anxiety displayed abnormal emotion identification. Only the anxious adolescents who were also characterized as being behaviorally inhibited during childhood displayed a lower threshold in identifying fear compared to anger. This suggests that perhaps temperamental differences in the samples of these previous studies may explain some of the previously found inconsistencies.

The findings of the current study should be considered in light of some limitations regarding both the emotion identification task and our sample. The current design did not include an assessment of valence or arousal ratings of the prototypical images which would have allowed for us to determine whether High BI adolescents with anxiety rate fearful faces as more unpleasant or arousing compared to other adolescents. Previous studies examining ratings of arousal and valence of fear and angry expressions between inhibited and non-inhibited adolescents (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2007) and between controls and adolescents with anxiety (McClure et al., 2007) have not found significant group differences; therefore, it is unlikely that the adolescents in our study would have displayed differences in their valence or arousal ratings. However, because these previous studies did not examine ratings in adolescents with a history of both BI and anxiety, it is still possible that High BI adolescents with anxiety rate fearful expressions differently compared to other adolescents.

There are also limitations to the conclusions that we can draw given our current sample. Because the current study was conducted on an all-Caucasian, middle to upper-middle class sample of adolescents, we are unable to generalize our current findings to other groups of adolescents of different racial or economic backgrounds. Also, although the sample size was relatively large, only a small portion of the participants developed an anxiety disorder, thus forcing us to combine adolescents with any history, both past and present, of anxiety disorder into a single group. Future studies with larger samples should consider examining the relation between BI and specific anxiety disorders. The current results suggest that the differences in facial emotion identification in behaviorally inhibited adolescents with anxiety may be specifically attributed to those with social anxiety. Given the small sample size of adolescents with social anxiety, these results should be replicated before final conclusions can be drawn. Moreover, because identification of emotional expressions and anxiety diagnosis were collected concurrently, this study was unable to establish whether over-identification of fear is a risk factor for later development of anxiety among behaviorally inhibited adolescents or is the result of being both anxious and behaviorally inhibited. Future studies should examine identification of facial affect in children at earlier ages in order to examine whether these differences exist prior to the manifestation of anxiety.

In summary, this study provides evidence that adolescents with both a childhood history of behavioral inhibition and lifetime history of anxiety, particularly social anxiety, process and identify fearful facial expressions differentially compared to those without such history. While other studies have reported differences in facial emotion identification between healthy and anxious individuals (Garner et al., 2009; Richards et al., 2002), this is the first to employ a longitudinal design to demonstrate that high-risk children who develop anxiety many years later display deficits in emotion identification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors report no conflicts of interest. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 MH074454 and R37 HD017899 to NAF. The authors thank the research staff who facilitated this work along with the children and their families for their continued participation in our studies.

References

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg M, van IJzendoorn M. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and non-anxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M, Ogliari A, Zanoni A, Villa F, Citterio A, Binaghi F, Maffei C. Children's discrimination of expressions of emotions: relationship with indices of social anxiety and shyness. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:358–365. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200403000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Pérez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, Fox NA. Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, editors. Social Phobia. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Coles ME, Heimberg RG. Memory biases in the anxiety disorders: current status. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:587–627. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RM, Rowe AC, Penton-Voak IS. The role of trait anxiety in the recognition of emotional facial expressions. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:1120–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easter J, McClure EB, Monk CS, Dhanani M, Hodgdon HB, Leibenluft E, Ernst M. Emotion recognition deficits in pediatric anxiety disorders: Implications for amygdala research. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychophamacology. 2005;15:563–570. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfenbein HA, Ambady N. On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:203–235. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Hane AA, Pine DS. Plasticity for affective neurocircuitry. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Calkins SD, Schmidt LA. Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influence across the first four years of life. Child Development. 2001;72:1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner M, Baldwin DS, Bradley BP, Mogg K. Impaired identification of fearful faces in generalised social phobia. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;115:460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, McClure EB, Adler AD, Brotman MA, Rich BA, Kimes AD, Leibenluft E. Specificity of facial expression labeling deficits in childhood psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2007;48:863–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herba C, Phillips M. Annotation: Development of facial expression recognition from childhood to adolescence: behavioural and neurological perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2004;45:1185–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarros RB, Salum GA, Belem da Silva CT, Toazza R, de Abreu Costa M, Fumagalli de Salles J, Manfro GG. Anxiety disorders in adolescence are associated with impaired facial expression recognition to negative valence. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EB, Monk CS, Nelson EE, Parrish JM, Adler A, Blair RJ, Pine DS. Abnormal attention modulation of fear circuit function in pediatric generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:97–106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EB, Pope K, Hoberman AJ, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Facial expression recognition in adolescents with mood and anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1172–1174. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melfsen S, Florin I. Do socially anxious children show deficits in classifying facial expressions of emotions? Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2002;26:109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Bradley BP. A cognitive-motivational analysis of anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;33:747–754. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JM, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA. Attention bias to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emotion. 2010;10:349–357. doi: 10.1037/a0018486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Reeb-Sutherland BC, McDermott JMN, White LK, Henderson HA, Degnan KA, Fox NA. Attention biases to threat link behavioral inhibition to social withdrawal over time in very young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:885–895. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9495-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Roberson-Nay R, Hardin MG, Poeth K, Guyer AE, Nelson EE, Ernst M. Attention alters neural responses to evocative faces in behaviorally inhibited adolescents. Neuroimage. 2007;34:1538–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Kistler DJ. Early experience is associated with the development of categorical representations for facial expressions of emotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 2002;99:9072–9076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142165999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeb-Sutherland BC, Helfinstein SM, Degnan KA, Pérez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Lissek S, Fox NA. Startle response in behaviorally inhibited adolescents with a lifetime occurrence of anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:610–617. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819f70fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeb-Sutherland BC, Vanderwert RE, Degnan KA, Marshall PJ, Pérez-Edgar K, Chronis-Tuscano A, Fox NA. Attention to novelty in behaviorally inhibited adolescents moderates risk for anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1365–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards A. Anxiety and the resolution of ambiguity. In: Yiend J, editor. Cognition, Emotion, and Psychopathology: Theoretical, Empirical and Clinical Directions. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2004. pp. 130–148. [Google Scholar]

- Richards A, Calder AJ, French CC, Webb B, Fox R, Young AW. Anxiety-related bias in the classification of emotionally ambiguous facial expressions. Emotion. 2002;2:273–287. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.2.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AK, Vasa RA, Bruck M, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Sweeney M, Team CAMS. Attention bias toward threat in pediatric anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:1189–1196. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825ace. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield CA, Coles ME, Gibb BE. Social anxiety and interpretation biases for facial displays of emotion: emotion detection and ratings of social cost. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2950–2963. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Snidman N, Kagan J. Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1008–1015. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvia PJ, Allan WD, Beauchamp DL, Maschauer EL, Workman JO. Biased recognition of happy facial expressions in social anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:585–602. [Google Scholar]

- Simonian SJ, Beidel DC, Turner SM, Berkes JL, Long JH. Recognition of facial affect by children and adolescents diagnosed with social phobia. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2001;32:137–145. doi: 10.1023/a:1012298707253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MJ, Batty M, Itier RJ. The faces of development: a review of early face processing over childhood. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16:1426–1442. doi: 10.1162/0898929042304732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veljaca K-A, Rapee RM. Detection of negative and positive audience behaviours by socially anxious subjects. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1998;36:311–321. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.