Abstract

The primate visual motion system performs numerous functions essential for survival in a dynamic visual world. Prominent among these functions is the ability to recover and represent the trajectories of objects in a form that facilitates behavioral responses to those movements. The first step toward this goal, which consists of detecting the displacement of retinal image features, has been studied for many years in both psychophysical and neurobiological experiments. Evidence indicates that achievement of this step is computationally straightforward and occurs at the earliest cortical stage. The second step involves the selective integration of retinal motion signals according to the object of origin. Realization of this step is computationally demanding, as the solution is formally underconstrained. It must rely--by definition--upon utilization of retinal cues that are indicative of the spatial relationships within and between objects in the visual scene. Psychophysical experiments have documented this dependence and suggested mechanisms by which it may be achieved. Neurophysiological experiments have provided evidence for a neural substrate that may underlie this selective motion signal integration. Together they paint a coherent portrait of the means by which retinal image motion gives rise to our perceptual experience of moving objects.

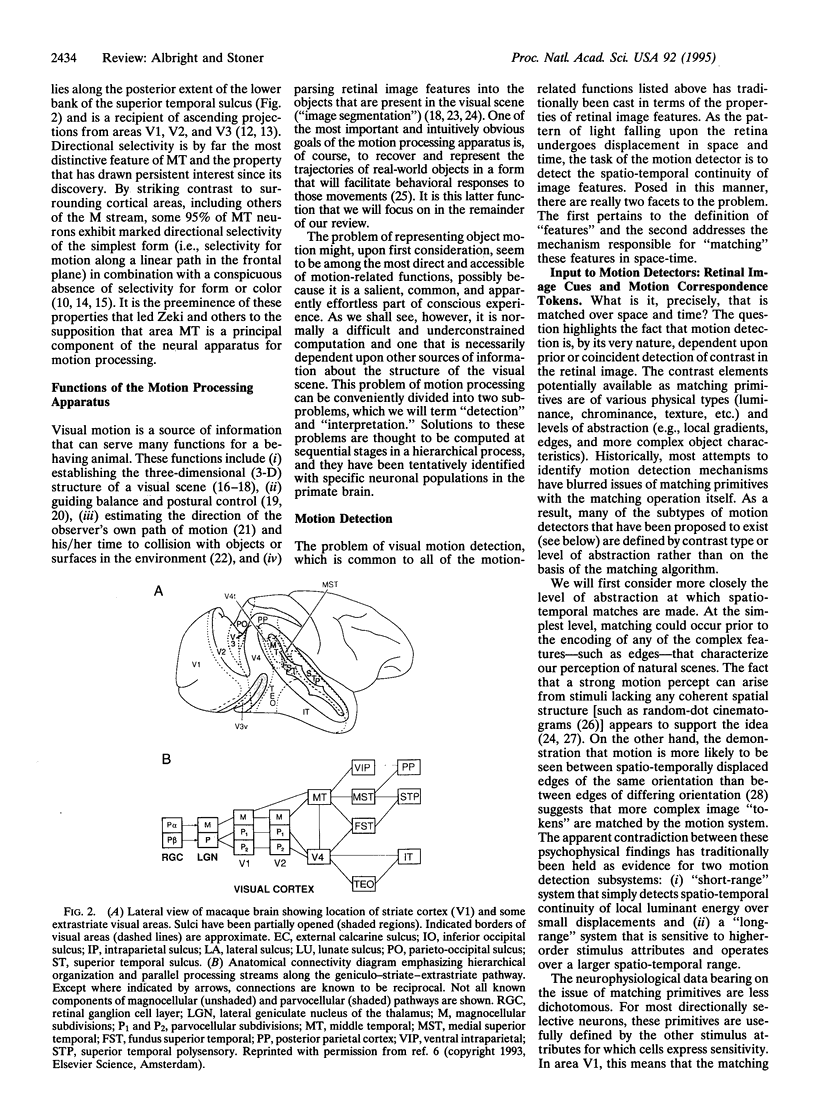

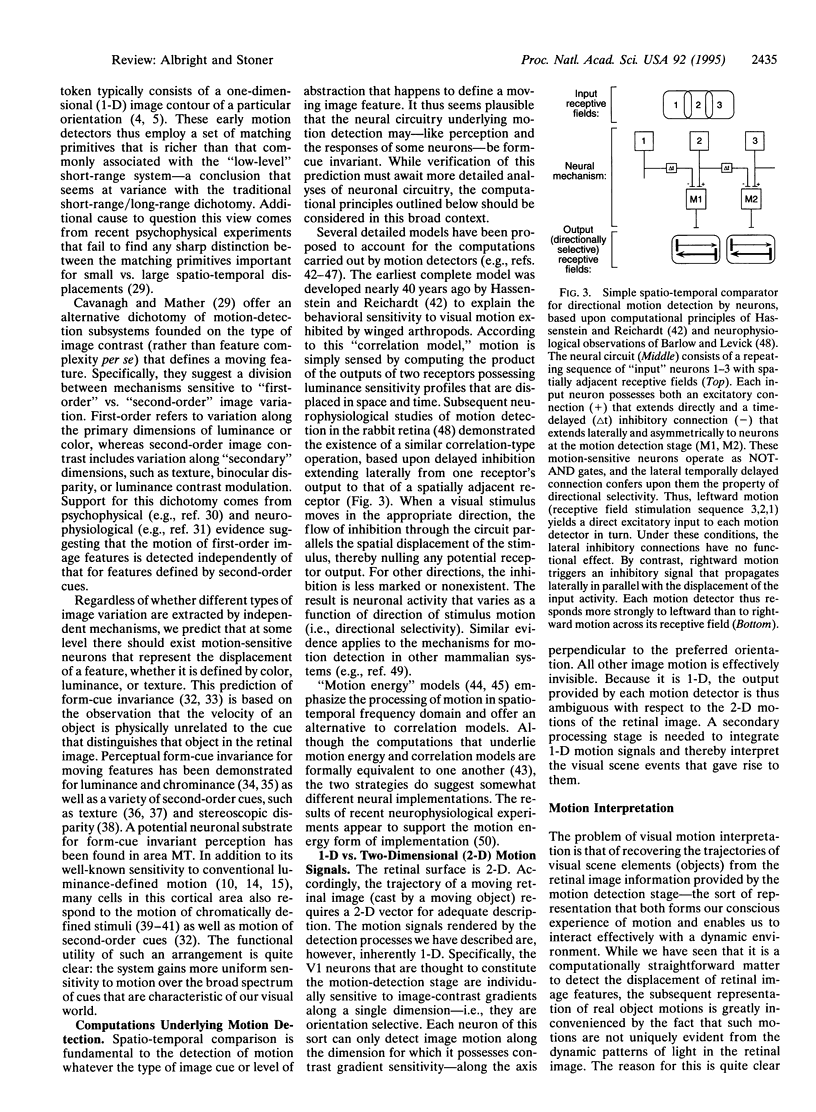

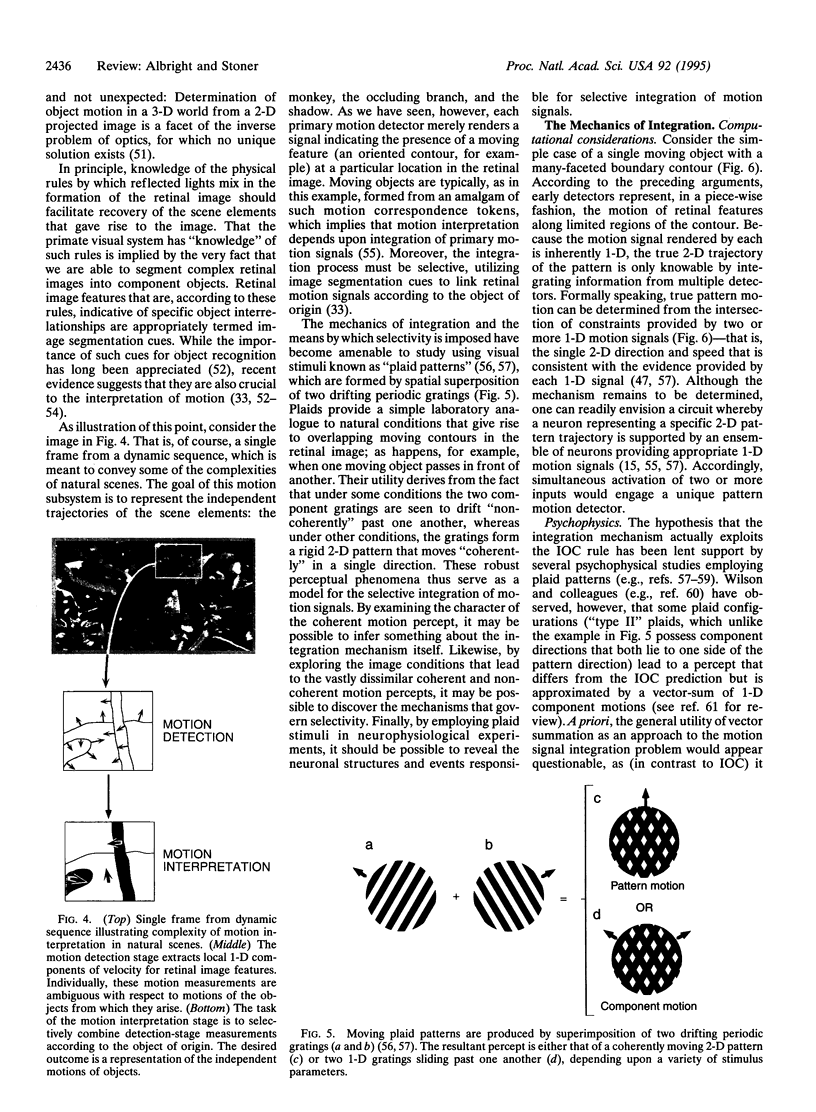

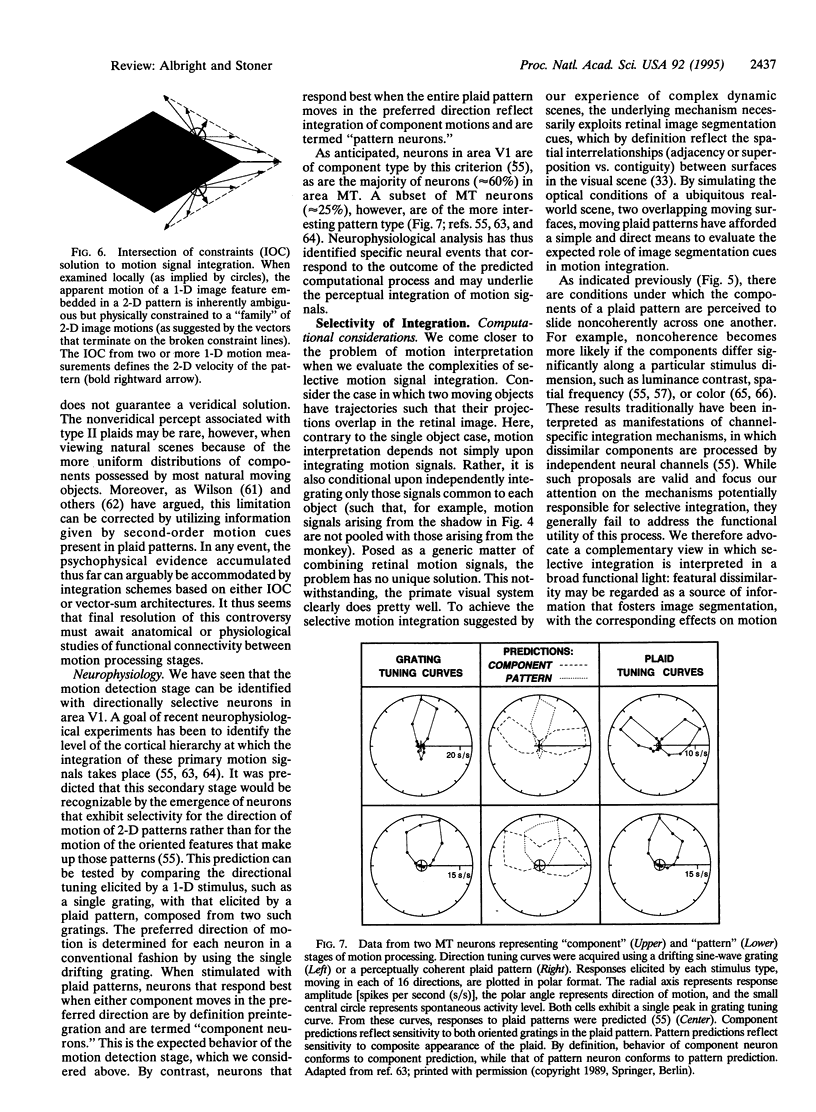

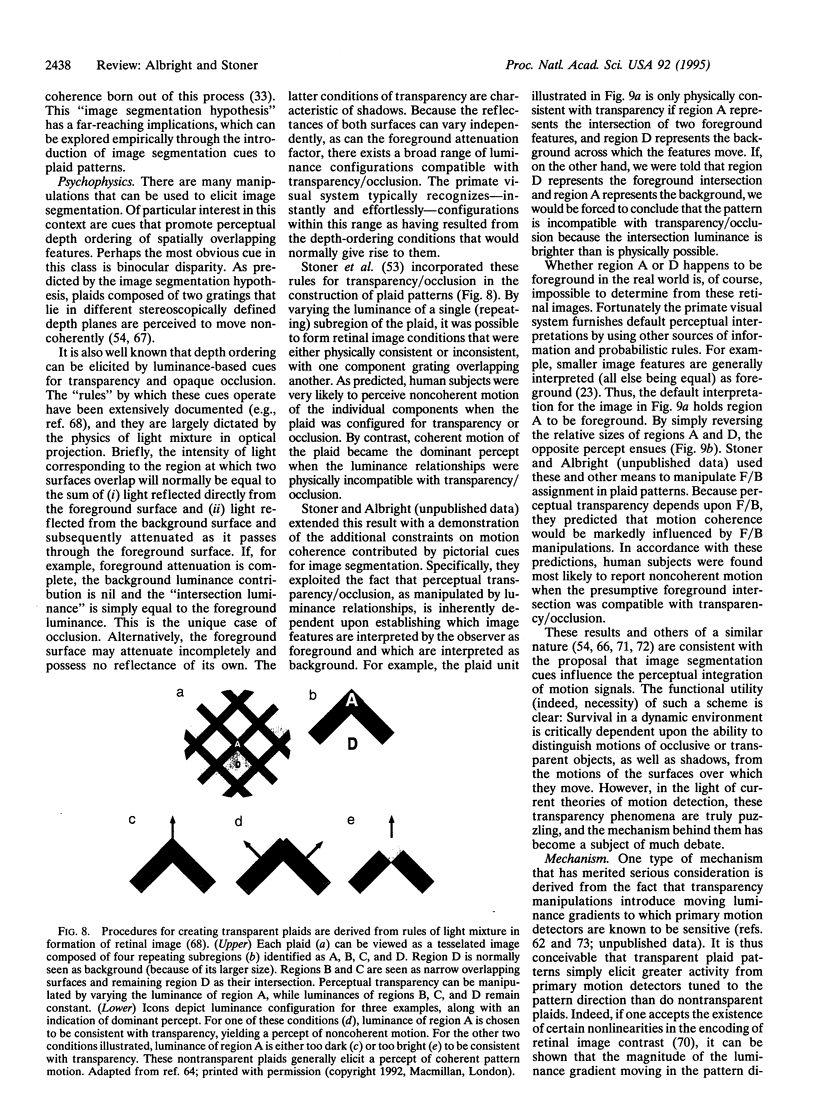

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adelson E. H., Bergen J. R. Spatiotemporal energy models for the perception of motion. J Opt Soc Am A. 1985 Feb;2(2):284–299. doi: 10.1364/josaa.2.000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelson E. H., Movshon J. A. Phenomenal coherence of moving visual patterns. Nature. 1982 Dec 9;300(5892):523–525. doi: 10.1038/300523a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albright T. D. Direction and orientation selectivity of neurons in visual area MT of the macaque. J Neurophysiol. 1984 Dec;52(6):1106–1130. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.52.6.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albright T. D. Form-cue invariant motion processing in primate visual cortex. Science. 1992 Feb 28;255(5048):1141–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1546317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman J. M., Kaas J. H. A representation of the visual field in the caudal third of the middle tempral gyrus of the owl monkey (Aotus trivirgatus). Brain Res. 1971 Aug 7;31(1):85–105. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstis S. M. Phi movement as a subtraction process. Vision Res. 1970 Dec;10(12):1411–1430. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(70)90092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow H. B., Levick W. R. The mechanism of directionally selective units in rabbit's retina. J Physiol. 1965 Jun;178(3):477–504. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braddick O. A short-range process in apparent motion. Vision Res. 1974 Jul;14(7):519–527. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(74)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke D., Wenderoth P. The effect of interactions between one-dimensional component gratings on two-dimensional motion perception. Vision Res. 1993 Feb;33(3):343–350. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(93)90090-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh P., Anstis S. The contribution of color to motion in normal and color-deficient observers. Vision Res. 1991;31(12):2109–2148. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh P., Mather G. Motion: the long and short of it. Spat Vis. 1989;4(2-3):103–129. doi: 10.1163/156856889x00077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb C., Sperling G. Drift-balanced random stimuli: a general basis for studying non-Fourier motion perception. J Opt Soc Am A. 1988 Nov;5(11):1986–2007. doi: 10.1364/josaa.5.001986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Valois K. K., De Valois R. L., Yund E. W. Responses of striate cortex cells to grating and checkerboard patterns. J Physiol. 1979 Jun;291:483–505. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkins K. R., Albright T. D. What happens if it changes color when it moves?: psychophysical experiments on the nature of chromatic input to motion detectors. Vision Res. 1993 May;33(8):1019–1036. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(93)90238-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkins K. R., Albright T. D. What happens if it changes color when it moves?: the nature of chromatic input to macaque visual area MT. J Neurosci. 1994 Aug;14(8):4854–4870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04854.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubner R., Zeki S. M. Response properties and receptive fields of cells in an anatomically defined region of the superior temporal sulcus in the monkey. Brain Res. 1971 Dec 24;35(2):528–532. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90494-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson R. C., Bergen J. R., Adelson E. H. Directionally selective complex cells and the computation of motion energy in cat visual cortex. Vision Res. 1992 Feb;32(2):203–218. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90130-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera V. P., Wilson H. R. Perceived direction of moving two-dimensional patterns. Vision Res. 1990;30(2):273–287. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(90)90043-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz L., Felder R. Mechanism of directional selectivity in simple neurons of the cat's visual cortex analyzed with stationary flash sequences. J Neurophysiol. 1984 Feb;51(2):294–324. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattass R., Gross C. G. Visual topography of striate projection zone (MT) in posterior superior temporal sulcus of the macaque. J Neurophysiol. 1981 Sep;46(3):621–638. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.46.3.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegenfurtner K. R., Kiper D. C., Beusmans J. M., Carandini M., Zaidi Q., Movshon J. A. Chromatic properties of neurons in macaque MT. Vis Neurosci. 1994 May-Jun;11(3):455–466. doi: 10.1017/s095252380000239x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray C. M., König P., Engel A. K., Singer W. Oscillatory responses in cat visual cortex exhibit inter-columnar synchronization which reflects global stimulus properties. Nature. 1989 Mar 23;338(6213):334–337. doi: 10.1038/338334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel D. H., Wiesel T. N. Receptive fields and functional architecture of monkey striate cortex. J Physiol. 1968 Mar;195(1):215–243. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julesz B., Payne R. A. Differences between monocular and binocular stroboscopic movement perception. Vision Res. 1968 Apr;8(4):433–444. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(68)90111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenderink J. J. Optic flow. Vision Res. 1986;26(1):161–179. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(86)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooi F. L., De Valois K. K., Switkes E., Grosof D. H. Higher-order factors influencing the perception of sliding and coherence of a plaid. Perception. 1992;21(5):583–598. doi: 10.1068/p210583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauskopf J., Farell B. Influence of colour on the perception of coherent motion. Nature. 1990 Nov 22;348(6299):328–331. doi: 10.1038/348328a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgeway T., Smith A. T. Evidence for separate motion-detecting mechanisms for first- and second-order motion in human vision. Vision Res. 1994 Oct;34(20):2727–2740. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)90229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone M., Hubel D. Segregation of form, color, movement, and depth: anatomy, physiology, and perception. Science. 1988 May 6;240(4853):740–749. doi: 10.1126/science.3283936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod D. I., Williams D. R., Makous W. A visual nonlinearity fed by single cones. Vision Res. 1992 Feb;32(2):347–363. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr D., Ullman S. Directional selectivity and its use in early visual processing. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1981 Mar 6;211(1183):151–180. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1981.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunsell J. H., Van Essen D. C. Functional properties of neurons in middle temporal visual area of the macaque monkey. I. Selectivity for stimulus direction, speed, and orientation. J Neurophysiol. 1983 May;49(5):1127–1147. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.49.5.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K., Loomis J. M. Optical velocity patterns, velocity-sensitive neurons, and space perception: a hypothesis. Perception. 1974;3(1):63–80. doi: 10.1068/p030063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K., Shimojo S. Toward a neural understanding of visual surface representation. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1990;55:911–924. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1990.055.01.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noest A. J., van den Berg A. V. The role of early mechanisms in motion transparency and coherence. Spat Vis. 1993;7(2):125–147. doi: 10.1163/156856893x00324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran V. S., Rao V. M., Vidyasagar T. R. Apparent movement with subjective contours. Vision Res. 1973 Jul;13(7):1399–1401. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(73)90219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodman H. R., Albright T. D. Single-unit analysis of pattern-motion selective properties in the middle temporal visual area (MT). Exp Brain Res. 1989;75(1):53–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00248530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H., Tanaka K., Isono H., Yasuda M., Mikami A. Directionally selective response of cells in the middle temporal area (MT) of the macaque monkey to the movement of equiluminous opponent color stimuli. Exp Brain Res. 1989;75(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00248524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller P. H., Finlay B. L., Volman S. F. Quantitative studies of single-cell properties in monkey striate cortex. I. Spatiotemporal organization of receptive fields. J Neurophysiol. 1976 Nov;39(6):1288–1319. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.6.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimojo S., Silverman G. H., Nakayama K. Occlusion and the solution to the aperture problem for motion. Vision Res. 1989;29(5):619–626. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(89)90047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner G. R., Albright T. D. Neural correlates of perceptual motion coherence. Nature. 1992 Jul 30;358(6385):412–414. doi: 10.1038/358412a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner G. R., Albright T. D., Ramachandran V. S. Transparency and coherence in human motion perception. Nature. 1990 Mar 8;344(6262):153–155. doi: 10.1038/344153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueswell J. C., Hayhoe M. M. Surface segmentation mechanisms and motion perception. Vision Res. 1993 Feb;33(3):313–328. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(93)90088-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider L. G., Mishkin M. The striate projection zone in the superior temporal sulcus of Macaca mulatta: location and topographic organization. J Comp Neurol. 1979 Dec 1;188(3):347–366. doi: 10.1002/cne.901880302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallortigara G., Bressan P. Occlusion and the perception of coherent motion. Vision Res. 1991;31(11):1967–1978. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen D. C., Maunsell J. H., Bixby J. L. The middle temporal visual area in the macaque: myeloarchitecture, connections, functional properties and topographic organization. J Comp Neurol. 1981 Jul 1;199(3):293–326. doi: 10.1002/cne.901990302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALLACH H., O'CONNELL D. N. The kinetic depth effect. J Exp Psychol. 1953 Apr;45(4):205–217. doi: 10.1037/h0056880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson A. B., Ahumada A. J., Jr Model of human visual-motion sensing. J Opt Soc Am A. 1985 Feb;2(2):322–341. doi: 10.1364/josaa.2.000322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch L. The perception of moving plaids reveals two motion-processing stages. Nature. 1989 Feb 23;337(6209):734–736. doi: 10.1038/337734a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeki S. M. Functional organization of a visual area in the posterior bank of the superior temporal sulcus of the rhesus monkey. J Physiol. 1974 Feb;236(3):549–573. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. X., Baker C. L., Jr A processing stream in mammalian visual cortex neurons for non-Fourier responses. Science. 1993 Jul 2;261(5117):98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.8316862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Santen J. P., Sperling G. Elaborated Reichardt detectors. J Opt Soc Am A. 1985 Feb;2(2):300–321. doi: 10.1364/josaa.2.000300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]