Summary

Recent evidence implicates glutamatergic synapses as key pathogenic sites in psychiatric disorders. Common and rare variants in the ANK3 gene, encoding ankyrin-G, have been associated with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and autism. Here we demonstrate that ankyrin-G is integral to AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission and maintenance of spine morphology. Using super-resolution microscopy we find that ankyrin-G forms distinct nanodomain structures within the spine head and neck. At these sites, it modulates mushroom spine structure and function, likely as a perisynaptic scaffold and barrier within the spine neck. Neuronal activity promotes ankyrin-G accumulation in distinct spine subdomains, where it differentially regulates NMDA receptor-dependent plasticity. These data implicate subsynaptic nanodomains containing a major psychiatric risk molecule, ankyrin-G, as having location-specific functions, and opens directions for basic and translational investigation of psychiatric risk molecules.

Introduction

Synaptic plasticity is thought to underlie learning and memory, tuning of neural circuitry and information storage in the brain. Two major postsynaptic processes are involved in plasticity of glutamatergic synapses: modifications in number of AMPA receptors (AMPARs) and alterations in size and shape of dendritic spines (Bosch and Hayashi, 2012). Spines are highly specialized and dynamic subcellular compartments that undergo structural plasticity (Sala and Segal, 2014). During one form of plasticity, long-term potentiation (LTP), spines become larger and more stable with an increased abundance of AMPARs, thereby strengthening synapse function (Makino and Malinow, 2009). The mechanisms by which this occurs have been extensively studied (Sala and Segal, 2014), though how this process may be disrupted in disease remains unclear.

Spines harbor an array of scaffolding proteins (including PSD95), which are responsible for localization of membrane proteins such as AMPARs, enabling optimum positioning for synaptic transmission. Spines are also highly enriched in cytoskeletal elements including F-actin and β-spectrin (Blanpied et al., 2008; Cingolani and Goda, 2008). Recent studies using super-resolution microscopy revealed that the organization of core synaptic components is more complex than previously appreciated; scaffolds and AMPARs are organized into subsynaptic domains that rearrange during plasticity (Kerr and Blanpied, 2012; MacGillavry et al., 2013; Nair et al., 2013). This phenomenon underscores the molecular complexity of the synapse, providing mechanistic insight into the workings of the PSD, and suggests how this function might go awry in pathogenic situations. Super-resolution imaging therefore enables discovery of previously unanticipated architectural and functional features of synapses.

Glutamatergic synapses and spine morphology have been implicated as key sites of pathogenesis in neuropsychiatric disorders including schizophrenia (SZ), autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) and intellectual disability (ID) (Penzes et al., 2013; Penzes et al., 2011). Genetic studies support these findings by implicating genes that encode synaptic proteins in the etiology of these disorders (Gilman et al., 2011; Nurnberger et al., 2014; Purcell et al., 2014). Synaptic deficits and reduced plasticity have also been linked to bipolar disorder (BD) (Lin et al., 2012), although the synaptic biology that contributes to pathogenesis of BD remains elusive. BD and other neuropsychiatric disorders may share common genetic risk factors, the study of which might reveal shared pathogenic mechanisms. The human ANK3 gene is a leading BD risk gene also associated with SZ, ASD and ID (Ferreira et al., 2008; Schulze et al., 2009). Rare pathogenic mutations in ANK3 were identified in patients with ID/ADHD (Iqbal et al., 2013) and ASD (Bi et al., 2012), making ANK3 a common genetic risk factor for neuropsychiatric diseases; however, the role that ANK3 may play in pathogenesis remains unknown.

ANK3 encodes ankyrin-G, a scaffolding-adaptor that links membrane proteins to the actin/β-spectrin cytoskeleton, organizing proteins into discrete domains at the plasma membrane (Bennett and Healy, 2009). Multiple isoforms of ankyrin-G exist in neurons, sharing 3 conserved domains: an N-terminal membrane association domain, a spectrin-binding domain and a C-terminal tail (Bennett and Healy, 2009). The 270/480kD isoforms have well-documented roles at the axon initial segment (AIS) and Nodes of Ranvier (NoR; Rasband, 2010). The role of the 190kD isoform in neurons, however, is less well characterized. Some studies have suggested that ankyrin-G may also reside at synapses: giant isoforms are essential for stability of the presynapse at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction (Koch et al., 2008; Pielage et al., 2008) and proteomic analyses have detected ankyrin-G in rodent PSD preparations (Collins et al., 2006; Jordan et al., 2004; Nanavati et al., 2011). It remains unclear how synaptic ankyrin-G might impact spine organization or plasticity and contribute to disease pathogenesis.

Here we demonstrate that ankyrin-G is integral to AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission and maintenance of spine morphology. Using super-resolution microscopy we find ankyrin-G forms distinct nanodomain structures within the spine head and neck. At these sites, it modulates mushroom spine structure and function, likely as a perisynaptic scaffold and barrier within the spine neck. We show that neuronal activity promotes ankyrin-G accumulation in spine subdomains, where it contributes to NMDA receptor-dependent plasticity. These data implicate subsynaptic nanodomains of a major psychiatric risk molecule, ankyrin-G, as having location-specific functions, and opens novel directions for basic and translational investigation of psychiatric risk molecules.

Results

Ankyrin-G knockdown impairs AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission and spine maintenance

Studies have suggested that ankyrin-G plays a role in neuronal function beyond its well-characterized actions at the AIS (Collins et al., 2006; Koch et al., 2008; Pielage et al., 2008). We hypothesized that ankyrin-G is involved in excitatory synaptic transmission. To test this, we utilized RNAi to knockdown ankyrin-G in mature cortical neuronal cultures. We tested four RNAi constructs in ankyrin-G transfected HEK cells (Figure S1A) and used the most effective (RNAi 4) experimentally (Figure S1B,C). RNAi 4 led to significant reduction of ankyrin-G levels in the soma, AIS and dendrites compared with control neurons (soma **p<0.01, AIS and dendrite ****p<0.0001, 2way ANOVA, Figure S1C).

To investigate synaptic function of ankyrin-G in neurons, we performed whole-cell electrophysiological recordings of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) from control and knockdown neurons (Figure 1A). Ankyrin-G knockdown caused a significant 26% reduction in mEPSC amplitude (*p=0.015, t-test, Figure 1B,C, Figure S1D) with no change in frequency (p=0.621, t-test, Figure 1D), suggesting that the effect of ankyrin-G knockdown is primarily postsynaptic. Since spine function and structure are linked, we tested whether ankyrin-G played a role in maintenance of spine morphology. Analysis of control or knockdown neurons imaged by confocal microscopy revealed that knockdown caused a significant 18% decrease in spine area (***p=0.0003, Figure 1E–G, Figure S1E), contributed to by both a decrease in spine length (**p=0.0015) and width (****p<0.0001, width:length: p=0.412, t-tests, Figure S1F). This effect on spine area was accompanied by an 18% decrease in spine density (*p=0.030, Figure 1H), however, concurrent with no effect on mEPSC frequency, there was no change in AMPAR cluster density as measured by confocal microscopy of knockdown neurons immunostained for GluA1 (Figure S1G). These experiments show that ankyrin-G is essential for maintaining proper AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission and spine structure in cortical neurons.

Figure 1. Ankyrin-G knockdown impairs synaptic transmission and spine maintenance.

(A) Representative AMPAR-mediated mEPSC traces from control or ankyrin-G knockdown neurons.

(B) Bar-graph of mEPSC amplitude. (32.76 ± 3.68 pA to 24.03 ± 1.21 pA, *p=0.015, n=15 cells).

(C) Cumulative probability graph of mEPSC amplitudes.

(D) Bar-graph of mEPSC frequency (p=0.621, n=15 cells, n.s.=non-significant)

(E) Confocal images of control or ankyrin-G knockdown neurons. Scale=5 µm.

(F) Bar-graph showing ankyrin-G RNAi causes a decrease in spine area compared with control (0.494 ± 0.16 µm2 to 0.404 ± 0.014 µm2, ***p=0.003, n=16–18 cells).

(G) Cumulative probability graph of spine areas (n=16–18 cells).

(H) Bar-graph showing ankyrin-G RNAi causes a decrease in spine density compared with control (8.39 ± 0.430 to 6.80 ± 0.534 spines/10 µm,*p=0.030, n=16–18 cells). See also Figure S1.

Ankyrin-G is present in dendrites and spines

The effects of ankyrin-G knockdown on mEPSCs and spine structure led us to investigate ankyrin-G at synaptic sites. Confocal imaging of neurons immunostained for endogenous ankyrin-G revealed the expected localization in the AIS (open arrowheads, Figure 2A), but also a robust presence at the plasma membrane of the soma (arrows) and puncta throughout the dendritic tree (arrowheads). We examined ankyrin-G antibody specificity using two additional antibodies and found that all three had similar distributions (Figure S2A). Immunoreactivity from our ankyrin-G pAb is highly reduced (~72%) in ankyrin-G knockdown neurons (Figure S2B) and specifically recognizes both GFP-tagged protein and bands of the correct molecular weight on western blots (Figure S2C). In GFP-expressing neurons, we observed ankyrin-G puncta in spines and along the dendritic shaft (Figure 2B). To confirm presence of ankyrin-G at synapses, we immunostained for ankyrin-G and either the presynaptic marker bassoon (Figure 2C) or postsynaptic scaffold PSD95 (Figure 2D); both markers exhibited substantial colocalization with ankyrin-G (Figure S2D). In cortical slices immunostained for ankyrin-G and bassoon, ankyrin-G also localized to the AIS and synaptic sites (Figure S2E). Our data thus indicate that endogenous ankyrin-G is present at synaptic sites in addition to the AIS.

Figure 2. Ankyrin-G forms nanodomains in the heads and necks of spines.

(A) Confocal image of a neuron immunostained for ankyrin-G in the soma (arrows), axon (open arrowheads) and dendrites (closed arrowheads). Scale=20 µm.

(B) Dendrite from neuron expressing GFP showing punctate ankyrin-G staining in the dendritic shaft and spines (arrowheads). Scale=5 µm.

(C,D) Confocal images of neurons stained for ankyrin-G and bassoon (C) and PSD95 (D). Arrowheads=colocalization. Scale=5 µm.

(E) SIM z-stack maximum projection of GFP-expressing neuron (left panel) immunostained for ankyrin-G (right panel, dendrite outlined in yellow). Scale=5µm.

(F) Ratiometric SIM images of spines expressing GFP and immunostained for ankyrin-G from image in (E). Arrowheads=spine head nanodomains, open arrowheads=spine neck nanodomains. Scale=0.2µm.

(G) SIM image of GFP-expressing neuron immunostained for ankyrin-G (red) and PSD95 (blue). Scale=5 µm. Box indicates spine in (H,I).

(H) Linescan through spine head from boxed spine in (G).

(I) 3D reconstruction of boxed spine in (G), Scale=1µm. See also Movie S1.

(J) SIM images of PSDs from GFP-expressing neurons immunostained for ankyrin-G and PSD95, scale=0.250 µm.

(K) Quantification of % of PSDs with each distribution.

(L) Schematic diagram of observed distributions of ankyrin-G nanodomains within spines. See also Figure S2.

Ankyrin-G forms discrete perisynaptic and neck nanodomains in spines

Recent studies indicate that molecules in spines are organized both spatially and functionally into subsynaptic domains (Chen and Sabatini, 2012; MacGillavry et al., 2011). We were therefore interested in the nanoscale organization of ankyrin-G at synapses with a view that this might reveal potential functions for this protein. Due to the limited resolution of confocal microscopy, we utilized a super-resolution microscopy technique: structured-illumination microscopy (SIM;(Gustafsson, 2005)). To analyze postsynaptic organization, we imaged cortical neurons expressing GFP and immunostained for ankyrin-G (Figure 2E), which revealed that ankyrin-G is not contained within a single homogenous complex, but is distributed into small domains throughout spine heads (Figure 2F). Surprisingly, we also found ankyrin-G localized to the spine neck (Figure 2F, open arrowheads), an understudied structure of the spine due to its size. Because the mean area of these domains was below the resolution of confocal microscopy, 131 ± 6 nm2, we termed them ‘nanodomains’.

To gain insight into the specific function of ankyrin-G, we analyzed the localization of ankyrin-G nanodomains relative to PSD95. We imaged GFP expressing neurons immunostained for ankyrin-G and PSD95 (Figure 2G–I and Figure S2F,G). Manders’ colocalization coefficients confirm that ankyrin-G overlaps with both PSD95 and bassoon to the same extent, and is both pre- and postsynaptic in cortical neurons, in agreement with previous reports of ankyrin-G location at the presynapse (Figure S2F,G (Pielage et al., 2008)). Frequently, multiple ankyrin-G nanodomains were found adjacent-to or directly overlapping with PSD95, with a mean distance from the center of an ankyrin-G nanodomain to the center of the PSD being 0.378 ± 0.015µm. A linescan through the spine head shows that peaks of fluorescence for ankyrin-G and PSD95 do not overlap (Figure 2H) and suggest a perisynaptic location for ankyrin-G as confirmed by 3D reconstruction (Figure 2I, Figure2I and Movie S1). We categorized synapses into three groups to describe the relationship of ankyrin-G nanodomains to PSD95: (i) single nanodomain, (ii) Multiple nanodomains around the PSD. (iii) Complete overlap of nanodomains (Figure S2H). 52% of spines fell into the second category, having 2 or more ankyrin-G nanodomains surrounding PSD95 (Figure 2J,K). Together, these SIM data led us to a model where ankyrin-G forms nanodomains in two main locations within the spine: in the spine head surrounding the PSD and within the spine neck (Figure 2L). Thus, ankyrin-G nanodomains are in a prominent position to potentially modulate glutamatergic synaptic transmission.

Ankyrin-G nanodomain localization associates with spine morphology

To understand how differential localization of ankyrin-G nanodomains may correlate with spine morphology, we analyzed neurons stained for endogenous ankyrin-G. Our analysis of spine morphology showed that we could precisely measure spine geometry using SIM (Figure 3A–D), producing values similar to other super-resolution imaging studies (Tonneson et al., 2014). Ankyrin-G nanodomains were present in 96% of spines and the number of nanodomains in the spine head directly correlated with the dimensions of the spine head (Figure 3F, Figure S3A,B). The mean ankyrin-G nanodomain area did not vary with spine head size (Figure 3E,G, Figure S3C,D), suggesting that they do not multimerize. PSD95 clusters had a mean area of 0.464 ± 0.024µm2 (Figure 3H,I), and this area correlated with the number of nanodomains in the spine head, rather than their mean area (Figure 3J,K). In addition to its presence in the spine head, 74% of spines had ankyrin-G nanodomains in the neck (Figure S3E), and 99% of these spines also had nanodomains in the head, correlating the presence of ankyrin-G in the neck to its presence in the head (Figure S3F). The presence of ankyrin-G in the spine neck in addition to the head directly correlated with the spine head area, as spines with neck nanodomains had significantly larger head areas compared with spines where ankyrin-G was absent from the neck, with no effect on the area of ankyrin-G or PSD95 clusters (Figure 3L). Together, these data suggest a distinct role for ankyrin-G at synapses that differs from classical scaffolding proteins such as PSD95; ankyrin-G is found in discrete nanodomains which are located both perisynaptically and in the spine neck. Moreover, the number of nanodomains in the spine head or associated with the PSD is correlated with both spine head size and PSD size, with the additional presence of ankyrin-G in the neck associated with larger spine heads.

Figure 3. Ankyrin-G nanodomain localization associates with spine morphology, based on SIM imaging.

(A–D) Frequency distributions of spine geometry: head area (A), head width –(B), neck width (C), neck length (D).

(E) Frequency distribution of ankyrin-G nanodomain area.

(F) Correlation plot of number of ankyrin-G nanodomains vs. spine head area, n=122 spines, 9 cells.

(G) Correlation plot of nanodomain area vs. area of spine head (n.s.).

(H) Frequency histogram of PSD95 puncta area.

(I) Bar graph showing mean nanodomain and PSD95 area, ****p=0.0001.

(J) Correlation plot of number of nanodomains vs. area of PSD.

(K) Correlation plot of nanodomain area vs. area of PSD (n.s).

(L) Bar graph of spine head, nanodomain and PSD95 areas in spines with ankyrin-G in the head and neck, or head only. Head area: 0.642 ± 0.031 µm2 to 0.490 ± 0.050 µm2, **p=0.0067, ankyrin-G nanodomain area: 0.153 ± 0.014 µm2 to 0.177 ± 0.023 µm2, p=0.174, PSD95 area: 0.511 ± 0.028 µm2 to 0.436 ± 0.072 µm2, p=0.350, n=122 spines, 9 cells. See also Figure S3.

A short form of ankyrin-G is localized to spines

There are multiple isoforms of ankyrin-G in the brain, with two of the most prevalent being the 190 and 270kD isoforms (Figure 4A (Bennett and Healy, 2009)). The 270kD isoform is restricted to axons due to the presence of a serine-rich domain and a long, C-terminal tail (Zhang and Bennett, 1998), however, the shorter 190kD isoform lacks these domains. Given our data showing endogenous ankyrin-G at the PSD and the prevalence of the 190kD isoform in the rat frontal cortex (Figure S4A), we hypothesized that the short isoform might be localized to spines. Consistent with this idea, synaptoneurosome preparations from rat cortex revealed significant enrichment of the 190kD isoform of ankyrin-G in synaptic lysate (Figure 4B). We expressed GFP-tagged 190kD and 270kD ankyrin-G in neurons and used confocal imaging to determine their localization (Figure 4C). Expression of GFPAnkG270 was restricted to the axon and soma with low expression in dendrites. In comparison, GFPAnkG190 was expressed in the AIS, soma, throughout the dendritic tree and in spines (Figure 4C, inset). Quantification of ankyrin-G abundance in axonal and dendritic compartments showed equal intensity of GFPAnkG190 in both compartments, compared with GFPAnkG270, which was far more localized to the axon (**p=0.0018, Figure 4D). Quantification of the fluorescence intensity of both isoforms in spines revealed 60% less spine localization of GFPAnkG270 compared with GFPAnkG190, and a reduced spine:shaft ratio (***p<0.0002, Figure 4E, S4B) suggesting that the 190kD isoform is localized at synaptic sites in cortical neurons.

Figure 4. A short isoform of ankyrin-G regulates spine maintenance.

(A) Schematic of the functional domains of 190kD and 270kD ankyrin-G isoforms. Note the serine-rich (Ser-rich) domain and tail insert are only present in the 270 kD isoform.

(B) SDS-PAGE and western blots of synaptoneurosomes probed with antibodies to ankyrin-G, PSD95 and spectrin. Lysate=whole cell cortical lysate, syn=synaptoneurosomes.

(C) Confocal images of neurons expressing GFPAnkG190 or GFPAnkG270, scale=20 µm. Open arrowheads=AIS. Inset=zoom of dendrite, scale=5 µm.

(D) Bar-graph showing dendrite:axon intensity ratio of GFPAnkG190 or GFPAnkG270 (**p=0.0018, n=8–10 cells).

(E) Bar-graph showing reduced intensity of GFPAnkG270 in spines compared with GFPAnkG190 (***p=0.0002, n=10–12 cells).

(F) Confocal images of neurons expressing mcherry alone, +GFPAnkG190 or +GFPAnkG270. Scale=5 µm.

(G) Bar-graph of spine area showing overexpression of GFPAnkG190 causes increased spine area compared with control, whereas overexpression of GFPAnkG270 causes a decreased spine area (0.485 ± 0.021 µm2 to 0.605 ± 0.036 µm2(AnkG190), or to 0.377 ± 0.016 µm2 (AnkG270), ****p=0.0001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, n=17–22 cells).

(H) Confocal images of cortical neurons transfected with control RNAi, ankyrin-G RNAi, ankyrin-G RNAi + 190rescue or ankyrin-G RNAi + 270rescue. Scale=5µm.

(I) Bar-graphs showing decreased spine area in knockdown neurons compared with control, rescued by 190kD but not 270kD expression (***p=0.0007, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, n=16–18 cells). See also Figure S4.

Ankyrin-G isoforms differentially regulate spine morphology

The differential distribution of ankyrin-G isoforms suggests that they may have distinct effects on spine morphology. We expressed GFPAnkG190 and GFPAnkG270 isoforms with mCherry in neurons and imaged them with confocal microscopy (Figure 4F). Overexpression of GFPAnkG190 caused a 24% increase in spine area compared with control (**p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA, Figure 4G), contributed by both an increase in spine length and head width, and no effect on spine density (Figure S4C), suggesting that at this mature time point, ankyrin-G190 is primarily modulating the maintenance of existing spines. Conversely, overexpression of GFPAnkG270 caused a 22% decrease in spine area (*p=0.0001, Figure 4F,G). To confirm a specific role for 190kD ankyrin-G in spine maintenance and growth, we coexpressed ankyrin-G RNAi with either RNAi-resistant AnkG190 or 270 constructs and assessed the ability of each to rescue the ankyrin-G knockdown phenotype. Confocal imaging revealed that RNAi-resistant constructs had the expected expression patterns (Figure S4D,E). RNAi-resistant GFPAnkG190 completely rescued the effects of RNAi knockdown, however coexpression of the GFPAnkG270 RNAi-resistant construct augmented the effects of RNAi knockdown (similar to its overexpression phenotype), causing a 24% decrease in spine area (Figure 4H,I and Figure S4F). This supports our hypothesis that ankyrin-G190 is primarily responsible for the effects we observe on spine morphology.

190kD ankyrin-G subspine localization impacts spine morphology

We then utilized SIM to precisely localize GFPAnkG190 in spines. We imaged neurons expressing mCherry and GFPAnkG190 and found enrichment of the 190kD isoform in spine heads and necks (Figure 5A). Linescans through the dendritic shaft and individual spines illustrate enrichment of GFPAnkG190 within the spine head (arrowheads) and peaks of fluorescence in the spine neck (open arrowheads). Within single spine heads, there are often multiple peaks of GFPAnkG190 fluorescence (Figure 5A, zoom), highlighted by linescans across the spine head (Figure 5B,C). SIM imaging of neurons expressing GFPAnkG190 and immunostained for PSD95 showed that GFPAnkG190 surrounds the central PSD rather than completely overlapping with it (Figure S5A), supporting a perisynaptic function for AnkG190 in the spine head.

Figure 5. 190kD ankyrin-G modulates spine head and neck width, based on SIM imaging.

(A) SIM image of neuron expressing GFPAnkG190. Scale=2 um. Box= spine in zoom; white lines=linescans in B,C. Scale=1 µm.

(B–C) Linescans of ankyrin-G intensity from shaft through neck and head (B), or across spine head (C).

(D–E) Bar-graphs of mushroom spine head (D) and neck (E) widths on overexpression of or absence of GFPAnkG190 compared with mcherry control, (**p=0.0071, **p=0.0023, n=131 spines)

(F) Bar-graphs of spine head area and neck width on overexpression or absence of GFPAnkG190 in the head only, split by spine type (head area: 0.395 ± 0.042 µm2 to 0.631 ± 0.046 µm2, **p=0.0015, neck width: p=0.367).

(G) Bar-graphs of spine head area and neck width on overexpression or absence of GFPAnkG190 in the head and neck, split by spine type (head area: 0.455 ± 0.034µm2 to 0.776 ± 0.103 µm2, **p<0.0018, neck width: 0.153 ± 0.003µm to 0.189 ± 0.009µm, ****p<0.0001).

(H) Schematic diagram showing GFPAnkG190 overexpression in the head only causes increased spine head area (F). However, additional overexpression in the neck increases spine head enlargement and neck thickening (G). See also Figure S5.

Given the correlations between endogenous ankyrin-G localization in the head and neck, and spine geometry we hypothesized that AnkG190 overexpression in these spine regions may impact spine morphology. We analyzed neurons overexpressing GFPAnkG190 and found that the presence of GFPAnkG190 anywhere in the spine causes enlargement of head and neck width in mushroom spines compared to spines without GFPAnkG190, or spines from neurons expressing mcherry alone (**p=0.0071, **p=0.0023, Figure 5D,E). This effect was specific to mushroom type spines and not thin spines (Figure S5B,C), although the overexpression of GFPAnkG190 caused no changes in the abundance of mushroom spines (Figure S5D). We then analyzed the effects of the presence of GFPAnkG190 overexpression in specific regions on spine geometry. Overexpression of GFPAnkG190 in the head significantly increased head area by 59% in mushroom spines only (**p=0.0015, Mann-Whitney U, Figure 5F), with no effect on neck width. In spines where GFPAnkG190 was overexpressed in the neck in addition to the head, there was a larger 70% increase in head area and 23% increase in neck width (**p<0.0018, ****p<0.0001, Mann-Whitney U, Figure 5G), with no effect on thin spines. Therefore the overexpression of GFPAnkG190 in mushroom but not thin spines causes changes in morphology, dependent on the location of GFPAnkG190; overexpression in the head only causes head enlargement whereas additional overexpression in the neck causes further head enlargement and neck thickening (Figure 5H).

β-spectrin-binding is essential for 190kD ankyrin-G localization and spine morphology

Ankyrin-G is known to be an essential link between the plasma membrane and the cytoskeleton (Bennett and Healy, 2009). We used STRING network analysis to identify candidate proteins that may act downstream of ankyrin-G to mediate the effects we observe on spines (Figure 6A). This revealed multiple membrane proteins but only one candidate likely to link ankyrin-G to the cytoskeleton, β-spectrin (SPTBN4). A binding partner and modulator of the actin cytoskeleton, β-spectrin has been shown to be present in spines (Ursitti et al., 2001). We hypothesized that the interaction between ankyrin-G and β-spectrin is required for ankyrin-G’s function. We created GFPAnkGAAA that contains a mutation rendering it unable to bind β-spectrin (Figure 6B, (Kizhatil et al., 2007)). This mutant displayed significantly reduced localization to spines compared with wild-type GFPAnkG190 (Figure 6C). Linescans of individual spines (Figure 6C, zooms) showed that enrichment of GFPAnkG190 in spine heads (*p<0.05 **p<0.01, 2-way ANOVA, Figure 6D) is abolished in neurons expressing the GFPAnkGAAA (Figure 6E, *p=<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001, 2-way ANOVA). Indeed, the mutant had a diffuse distribution with significantly higher expression in the dendritic shaft and collection at the base of spines (*p=<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001, 2-way ANOVA, Figure 6F). The spine to shaft ratio of GFPAnkGAAA was reduced significantly by 36% (Figure 6G) and more than 60% of spines had a spine to shaft ratio of 0.5 or less (Figure S6A), indicative of enrichment in the dendritic shaft rather than in the spine head. GFPAnkGAAA expression caused a decrease in spine area, contrary to the increase seen with GFPAnkG190 overexpression (**p<0.0001, *p<0.001; p<0.05, one-way ANOVA, Figure 6H). The interaction between ankyrin-G and β-spectrin therefore is critical for targeting ankyrin-G to spines in cortical neurons.

Figure 6. β-Spectrin-binding is crucial for ankyrin-G synaptic targeting and function.

(A) STRING analysis of ANK3 interactors. Red rectangle highlights ANK3-SPTBN4 (β-spectrin) interaction. Line colors represent types of evidence: pink=experimental, green=text mining, blue=databases, purple=homology.

(B) Schematic showing the functional domains of 190kD isoform of ankyrin-G and the 999DAR/AAA mutation that disrupts ankyrin-G binding to β-spectrin.

(C) Confocal images of neurons expressing mcherry alone, +GFPAnkG190 or +GFPAnkGAAA, scale=5µm. Zoom of spines with example linescan, arrowheads=AnkG in head or shaft, scale bar=1µm.

(D–F) Linescan analysis of GFPAnkG190 and GFPAnkGAAA in spines cotransfected with mcherry, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, n=7–12 cells.

(G) Spine:shaft ratios of GFPAnkG fluorescence intensity show a decrease in ratio for GFPAnkGAAA compared to GFPAnkG190 (**p=0.0012, n=6 cells).

(H) Bar graph of effects of GFPAnkG190 and GFPAnkGAAA overexpression on spine area (**p<0.01, *p<0.01, n=12–20 cells).

(I) Bar graph of spine areas in the presence or absence of GFPAnkG190 or GFPAnkGAAA (***p<0.001, n=12–13 cells).

(J) Bar graph of % spine enlargement in the presence or absence of GFPAnkG190/AAA (*p=0.0213, n=11–13 cells).

(K) Confocal images of neurons expressing GFP, GFPAnkG190 or GFPAnkGAAA and immunostained for GluA1. Scale=5µm.

(L) Bar graph of GluA1 cluster area quantification (0.216 ± 0.013 to 0.253 ± 0.009, *p=0.03, n=11–16 cells). See also Figure S6.

We also asked if the interaction between ankyrin-G and β-spectrin was important for spine enlargement. We analyzed the area of spines imaged by confocal microscopy and categorized by the presence or absence of GFPAnkG190 or GFPAnkGAAA. Spines containing GFPAnkG190 were 47% larger than spines without (***p<0.001, one-way ANOVA, Figure6I) but there was no difference between the areas of spines containing GFPAnkGAAA compared with spines without (p=n.s, one-way ANOVA). Spines with GFPAnkG190 demonstrated 32% enlargement compared to spines containing GFPAnkGAAA, which only showed 20% enlargement (*p=0.0213, t-test, Figure 6J). Likewise, in SIM analysis, GFPAnkGAAA overexpression abolished the effects of GFPAnkG190 overexpression on mushroom spines (Figure 5G). Neither head area nor neck width were increased, even with GFPAnkGAAA in both the head and neck (Figure S6C). Even when GFPAnkGAAA is targeted to spines, its ability to increase spine size is compromised, showing that the ability of ankyrin-G to bind β-spectrin is not only important for ankyrin-G targeting but also for mediating changes in morphology. We then tested the impact of 190kD ankyrin-G on AMPAR clusters by analyzing GluA1 cluster area in neurons transfected with GFPAnkG190 or GFPAnkGAAA. We found a 17% increase of cluster area with expression of GFPAnkG190, which was abolished with GFPAnkGAAA (*p=0.031, oneway ANOVA, Figure 6K,L), further pointing to the necessity of the ankyrin-G-β-spectrin interaction for correct spine morphology and AMPAR clustering.

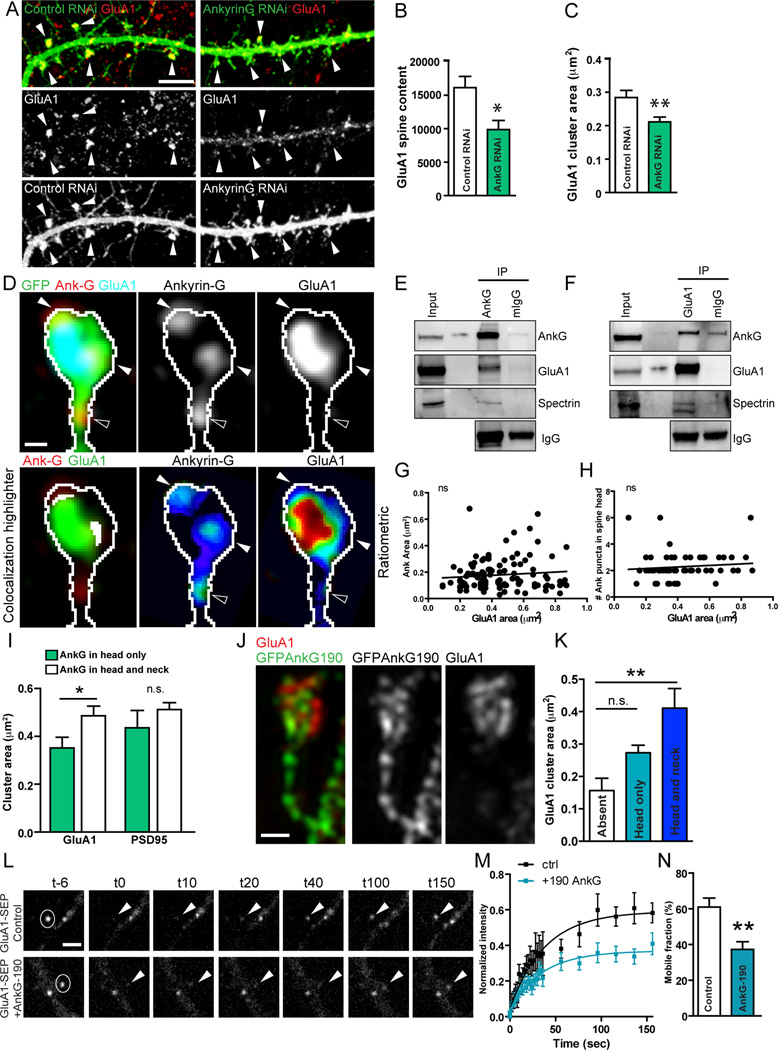

Ankyrin-G regulates AMPARs in dendritic spines

Our electrophysiological experiments show that ankyrin-G knockdown reduces mEPSC amplitude (Figure 1A–C), suggesting reduction in synaptic AMPARs. We were able to rescue this phenotype by coexpression of RNAi-resistant AnkG190 (Figure S7A–C), suggesting that synaptic ankyrin-G may play a role in AMPAR regulation in spines. Confocal imaging of neurons costained for ankyrin-G and GluA1 revealed that 60% of ankyrin-G puncta colocalized with GluA1 puncta (Figure S7D,E). To test whether ankyrin-G modulates GluA1 clustering in spines we immunostained ankyrin-G RNAi transfected neurons for GluA1, followed by confocal imaging (Figure 7A). Ankyrin-G knockdown generated a 38% reduction in GluA1 intensity in the spine and a 22% reduction in GluA1 cluster area (intensity:*p=0.0106, area:*p=0.045, t-test, Figure 7B,C), pointing to a mechanism where ankyrin-G knockdown reduces GluA1 levels in spines, and accounts for the reduced mEPSC amplitude.

Figure 7. Ankyrin-G confines AMPARs to spines.

(A) Confocal images of control or knockdown neurons immunostained for GluA1 (red). Arrowheads=GluA1 in spines. Scale=5µm.

(B–C) Bar-graphs showing quantification of GluA1 spine content (B) and cluster area (C) (from 0.287 ± 0.022 µm2 to 0.210 ± 0.011 µm2, *p=0.011,**p=0.0041, n=11–14 cells).

(D) SIM images of a spine from a GFP-expressing neuron immunostained for ankyrin-G (red) and GluA1 (blue). Scale=0.2µm. Closed arrowheads=spine head nanodomains, open arrowheads=neck nanodomains. White in lower left panel=colocalization highlighter. Last two panels show ratiometric images of ankyrin-G and GluA1 localization, respectively.

(E,F) Western blots of coimmunoprecipitation experiments of ankyrin-G with GluA1 from rat cortex. mIgG=control mouse IgG, IP=immunoprecipitation.

(G,H) Correlation plots of nanodomain area (G) and number in the spine head (H) vs. GluA1 puncta area.

(I) Bar graph showing GluA1 and PSD95 puncta area in spines with ankyrin-G in the head only, or in the head and neck, *p=0.033.

(J) SIM image of spine from GFPAnkG190 expressing neuron immunostained for GluA1. Scale=0.2µm.

(K) Bar graph showing GluA1 puncta area in spines with GFPAnkG190 overexpressed in the head only, or in the head and neck (*p=0.04, n=75 spines).

(L) Representative timelapse of GluA1-SEP fluorescence recovery in control or AnkG190 overexpressing neurons in FRAP experiment. Scale=1µm.

(M) Quantification of GluA1-SEP fluorescence cluster intensity over time. Data are fitted with single exponentials (colored lines).

(N) Bar graph of mobile fraction in control and AnkG190 overexpressing neurons (60.95 ± 5.0 to 37.26 ± 4.3%, **p=0.0072, n=10 cells). See also Figure S7.

To understand the mechanism underlying regulation of AMPAR by ankyrin-G, we used SIM to examine subsynaptic localization with GluA1. Ankyrin-G nanodomains were partially overlapping with and around GluA1 clusters (Figure 7D and Figure S7F). Indeed, the mean distance between the center of GluA1 and ankyrin-G was 0.381 ± 0.021 µm, very similar to that of PSD95 and ankyrin-G, supporting a perisynaptic localization for ankyrin-G. This partial colocalization suggests that ankyrin-G may interact with AMPARs. To test this in vivo, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments from rat cortical lysate, showing that ankyrin-G interacts in a complex with GluA1 and β-spectrin (Figure 7E,F).

A significant fraction of ankyrin-G in spines did not colocalize with GluA1, suggesting other potential mechanisms of regulation. GluA1 cluster size was not correlated with ankyrin-G nanodomain area or number in the spine head (Figure 7G,H). However, in spines where ankyrin-G was present in the neck in addition to the head, the mean GluA1 cluster area was significantly increased by 38% (*p=0.033, t-test, Figure 7I), whereas the PSD95 area was independent of the presence of ankyrin-G in the neck (p=0.350), and solely dependent on ankyrin-G in the head. To assess the effects of ankyrin-G presence in the neck in addition to the head on GluA1 clusters we imaged neurons overexpressing GFPAnkG190 and immunostained for GluA1 (Figure 7J). Overexpression of GFPAnkG190 in the head and neck caused a significant increase in GluA1 cluster area, whereas overexpression in the head alone did not have significant effects (p=0.004, one-way ANOVA, Figure 7JK).

If ankyrin-G contributes to scaffolding or retention of AMPARs in spines we would expect alterations in AMPAR surface dynamics upon manipulation of ankyrin-G expression. We performed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of GluA1-SEP clusters to measure AMPAR mobility in neurons overexpressing AnkG190. Overexpression of AnkG190 reduced the amount of GluA1-SEP fluorescence recovery in spines compared with control neurons (Figure 7L,M), and calculation of the total mobile fraction of GluA1-SEP in each condition revealed a 39% decrease in GluA1-SEP mobility in AnkG190 overexpressing neurons compared with control (p=0.072, t-test, Figure 7N). This suggests ankyrin-G overexpression in spines increases AMPARs stability.

Ankyrin-G contributes to the regulation of chemical LTP induced spine plasticity

Due to the effects that manipulation of ankyrin-G expression had on spine morphology and function, we hypothesized that ankyrin-G might play a role in activity-dependent spine plasticity. We used a well-characterized chemical LTP (cLTP) protocol shown to cause rapid activation of NMDA receptors, causing increased spine area and density (Chung et al., 2004; Liao et al., 2001; Xie et al., 2007). We performed cLTP with control or knockdown neurons, imaged them by confocal microscopy, and analyzed spine area and density (Figure 8A–C). We observed significant increases in spine size (27%) and density (25%) (Area:**p=0.0023, density:*p=0.023, t-tests, Figure 8B,C), although in ankyrin-G knockdown neurons, there were no such increases following cLTP treatment (Area:p=0.710, density:p=0.663, t-tests, Figure 8B,C), suggesting that ankyrin-G knockdown occludes the structural changes induced by cLTP.

Figure 8. Ankyrin-G in dendritic spines is required for LTP.

(A) Confocal images of control or knockdown neurons treated with control or chemical LTP (cLTP) protocol. Scale=5 µm.

(B,C) Bar graphs of spine areas (B) and spine density (C) in control or cLTP conditions, in control or knockdown neurons (**p=0.0023, *p=0.023, n=14–19 cells)

(D) Confocal images of control and cLTP treated cortical neurons expressing GFP and costained with ankyrin-G (red). Arrowheads= ankyrin-G puncta. Scale=5 µm.

(E) Quantification of spine:shaft ratio of ankyrin-G after treatment with cLTP protocol (**p<0.01, n=12–15 cells).

(F) SIM images of spines from GFP-expressing cortical neurons stained for ankyrin-G (red) in control or cLTP conditions. Scale=0.25 µm.

(G) Bar-graph showing increased spine head area in cLTP vs. control, based on SIM images (0.530 ± 0.040 µm2 to 0.662 ± 0.040 µm2, **p=0.0096, n=71–80 spines).

(H) Bar-graph showing increased nanodomain number in spine heads after cLTP, based on SIM imaging, ***p<0.0001, n=67–70 spines.

(I) Graph of correlation between change in spine head area of cLTP spines compared with mean control spine area, and number of ankyrin-G nanodomains in the spine head, as determined by immunostining for ankyrin-G subsequent to cLTP. ***p<0.0001, Spearman correlation=0.74.

(J) Bar-graph showing increased spine neck width after cLTP treatment compared with control, based on SIM images (from 0.152 ± 0.006 µm to 0.183 ± 0.005 µm, ***p<0.0001, n=55–67 spine necks).

(K) Bar-graph of spine head area after cLTP treatment in spines with/without ankyrin-G in their necks, based on SIM images (*p=0.037, n=71–80 spines).

(L) Bar-graph of spine neck width after cLTP treatment in spines with/without ankyrin-G in their necks, based on SIM images (**p=0.009, **p=0.007, n=71–80 spines).

(M) SIM images of control or cLTP treated neurons immunostained for ankyrin-G (red) and GluA1 (green). Scale=2µm.

(N) Bar-graph showing increased overlap of ankyrin-G nanodomains with GluA1 clusters after cLTP (***p=0.0002, n=5 cells).

(O–Q) Analysis of ankyrin-G distribution in hippocampal cytoskeletal (P), membrane (Q) and cytosolic (R) subcellular fractions from naïve or fear conditioned mice. Western blots: upper blots are probed with ankyrin-G and lower blots are probed with actin (*p=0.045,**p= 0.0067, n=5 mice). See also Figure S8.

Ankyrin-G accumulates in synapses during cLTP

We next asked how ankyrin-G might be involved in spine enlargement during cLTP. We costained GFP-transfected neurons for ankyrin-G and imaged them by confocal microscopy (Figure 8D). Ankyrin-G accumulated in spines after cLTP treatment, characterized by an increase in the ankyrin-G spine to shaft ratio (**p=0.0041, Mann-Whitney U, Figure 8E). We used SIM to assess changes in distribution of ankyrin-G nanodomains after cLTP (Figure 8F). We again saw increases in spine head area (24%), width (16%) and length (12%) (area:**p=0.0096, width:*p=0.018, length:*p=0.047, Mann-Whitney U, Figure 8G; Figure S8A–C), which corroborates recent super-resolution studies (Tonnesen et al., 2014). The number of nanodomains in the spine head increased significantly after cLTP treatment (Figure 8H) even when normalized to spine head area (Figure S8D), suggesting that the increase in ankyrin-G nanodomain number is not solely due to increased spine head size, but that ankyrin-G is enriched in the spine head after cLTP. Correlations between spine head area and ankyrin-G nanodomain number were similar for both control and cLTP conditions (Figure S8E,F). Spine head enlargement after cLTP correlated significantly with the number of ankyrin-G nanodomains in the spine head, with no enlargement in spines lacking ankyrin-G (Figure 8I), underlining the potential importance of ankyrin-G in this process. Spine neck width increased by 20% after cLTP treatment (***p<0.0001, Mann-Whitney U, Figure 8J), with no change in spine neck length (p=0.303, Mann-Whitney U, Figure S8G). Interestingly, spines with ankyrin-G in their neck in addition to their head did not undergo cLTP-dependent spine head enlargement (Figure 8K), potentially due to the fact that this subset of spines already has large head areas which might not be able to expand further. Presence of ankyrin-G in the spine neck had no impact on the effect of cLTP on spine neck width (Figure 8L), supporting a role for ankyrin-G in regulating spine neck width, in basal and active conditions. SIM imaging of neurons immunostained for ankyrin-G and GluA1 showed a significant increase in overlap between ankyrin-G nanoclusters and GluA1 (from 8% to 23%, ***p=0.0002, Figure 8M,N), suggesting that ankyrin-G moves to overlap more fully with AMPARs during cLTP.

Increased association of ankyrin-G with the plasma membrane and cytoskeleton in vivo

To determine whether AnkG190 translocates in vivo in response to a physiological learning paradigm, we analyzed subcellular fractions from the hippocampus of mice subjected to fear conditioning, a well-characterized model of learning and memory. AnkG190 was enriched in the membrane (84%) and cytoskeletal fractions (60%) from trained compared with naïve mice, but not in the cytosolic fraction (cytoskeleton:*p=0.045, membrane:**p=0.0067, cytosol:p=0.488, t-tests, Figure 8O–Q). These data suggest that ankyrin-G has greater association with both the cell membrane and cytoskeleton following a learning task in mice.

Discussion

ANK3 (ankyrin-G) is emerging as a shared risk factor for multiple psychiatric disorders including SZ, ASD, ID and BD (Bi et al., 2012; Ferreira et al., 2008; Iqbal et al., 2013; Schulze et al., 2009). These disorders are unified by glutamatergic synapse pathology, yet little is known about potential functions of ankyrin-G in spines. Roles for ankyrin-G at other types of synapses have begun to emerge: organizing GABAergic synapses at the AIS (Huang et al., 2010) and stabilizing presynaptic structure at the Drosophila NMJ (Pielage et al., 2008). Our data support a model (Figure S8H–J) whereby ankyrin-G functions at glutamatergic synapses and thereby may contribute to disease. Super-resolution microscopy identified ankyrin-G nanodomains localized perisynaptically in the spine head and also in the spine neck. These nanodomains contribute to AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission by controlling AMPAR cluster stability, spine head size, neck width, and cLTP-dependent spine enlargement. Furthermore, stimuli that induce plasticity or learning in vivo induce accumulation of ankyrin-G to synapses, the cytoskeleton and membranes, thus supporting a role for ankyrin-G in synaptic plasticity and a mechanism by which the glutamatergic synaptic pathology may be mediated in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Super-resolution imaging identifies subsynaptic ankyrin-G nanodomains

Confocal imaging indicated the presence of ankyrin-G in spines and its colocalization with glutamatergic synaptic markers; however, the resolution of this technique does not reveal subsynaptic detail. The advent of super-resolution microscopy has facilitated imaging beyond the diffraction limit of light, providing unprecedented insight into subcellular architecture (Tonnesen and Nagerl, 2013). Several recent studies have used these techniques to reveal that AMPARs, PSD95, actin and CaMKII are localized to subsynaptic domains (Frost et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2014; MacGillavry et al., 2013; Nair et al., 2013). Super-resolution approaches have not yet been used to investigate synaptic function of newly identified psychiatric risk genes. Our measurements of spine geometry derived from SIM images are consistent with other reports using super-resolution microscopy (Tonnesen et al., 2014), and we observe very similar changes in spine neck width during LTP, underlining the accuracy of our imaging technique. Ankyrin-G forms nanodomains of ~130nm in diameter, 3 times smaller than the PSD itself and organizes perisynaptically and in the spine neck. This is in contrast to ‘classical’ PSD scaffolds that are large heterogeneous platforms (MacGillavry et al., 2011). This difference is highlighted by the observation that ankyrin-G nanodomain number but not area correlates with spine head size, suggesting that they are discrete entities and do not multimerize. Ankyrin-G nanodomains were not located directly within the PSD, but surrounding the PSD, or within the spine neck away from the synapse. PALM imaging has recently identified a similar localization for CamKII, a key protein involved in synaptic plasticity (Lu et al., 2014). Our SIM localization data suggest a novel function for ankyrin-G that differs from a ‘classical’ PSD scaffolding protein.

Ankyrin-G nanodomain function in spines

At the AIS, ankyrin-G is known to mediate recruitment and organization of molecules, but how ankyrin-G may regulate the structure and function of glutamatergic synapses is unknown. We show that β-spectrin is in a complex with ankyrin-G and AMPARs. β-spectrin is a component of the submembranous cytoskeleton, previously reported to interact with ankyrin-G (Bennett and Healy, 2009), is abundant in dendrites and spines (Ursitti et al., 2001) and has been shown to regulate spine morphology by bundling actin filaments (Nestor et al., 2011). By introducing point mutations known to abolish ankyrin-G’s interaction with β-spectrin, we prevented targeting of ankyrin-G to spines and caused a reduction in spine size. This mutation also abolishes the effect of AnkG190 overexpression on spine head area, neck width and GluA1 cluster area, pointing to β-spectrin being a major mediator of ankyrin-G function in spines. This is similar to interactions at the Drosophila NMJ, where β-spectrin recruits ankyrin2 and is responsible for the structure and organization of the synapse (Pielage et al., 2006). These results indicate that interaction with the cytoskeleton, through β-spectrin, is important for both localization of ankyrin-G to spines and its function at synapses.

At the nanoscale, ankyrin-G showed only partial overlap with PSD95 with a mean distance of 378nm between the centre of PSD95 puncta and the surrounding ankyrin-G nanodomains. This perisynaptic position of ankyrin-G corresponds with the pool of F-actin that resides ~300 nm from the PSD center (Frost et al., 2010), placing ankyrin-G in an ideal position to modulate this pool of actin. Indeed, the morphology of the PSD is dynamically regulated by the actin cytoskeleton that surrounds it (Blanpied et al., 2008) and this can have direct effects on clustering of AMPARs and efficacy of synaptic transmission (MacGillavry et al., 2013). We found that spine head and PSD size correlated with the number of ankyrin-G puncta in the spine head, suggesting that ankyrin-G may link to the actin cytoskeleton and be important for modulation of the PSD. Ankyrin-G nanodomains also partially overlap with GluA1 puncta in spines, showing perisynaptic localization based on SIM. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments indicate that ankyrin-G, AMPARs and β-spectrin participate in a common complex, supporting our model in which ankyrin-G links a perisynaptic pool of AMPARs to the β-spectrin-actin cytoskeleton, therefore stabilizing these receptors. Our FRAP data showed overexpression of AnkG190 caused a significant reduction in AMPAR mobility in spines, further supporting the function of ankyrin-G as an additional synaptic scaffold. The interaction between ankyrin-G and GluA1 is likely to be indirect and could be mediated by multiple proteins, such as the accessory protein stargazin which mediates the interaction between AMPARs and PSD95 (Bats et al., 2007) and the β-spectrin-actin cytoskeleton adaptor protein 4.1N, which regulates the exocytosis of GluA1-AMPARS (Lin et al., 2009). It is also important to emphasize that ankyrin-G may be mediating these effects by altering the actin cytoskeleton which could cause changes in receptor scaffolding, trafficking and other related indirect mechanisms.

In addition to their perisynaptic localization, ankyrin-G nanodomains were present in the neck of 74% of spines analyzed. Localization in spine neck is particularly intriguing, as it has been reported for few other proteins including DARPP-32 (Blom et al., 2013), septin 7 (Tada et al., 2007), and synaptopodin (Deller et al., 2000). At the AIS, ankyrin-G acts as a barrier to limit the lateral mobility of ion channels and protein diffusion (Rasband, 2010). The additional presence of ankyrin-G in the spine neck correlated with increased size of AMPAR clusters in the spine head, but not the size of the PSD, again suggesting a role for modulating the abundance of dynamic, diffusive proteins, rather than the relatively static PSD. Ankyrin-G may act as a barrier in the spine neck, limiting the mobility of GluA1 out of the spine, promoting the retention of AMPARs in the spine head and thereby maintaining synaptic function. This proposed mechanism is supported by experimental data and mathematical models that indicate that the spine neck plays an essential role in limiting diffusion (Ashby et al., 2006; Kusters et al., 2013; Simon et al., 2014).

Ankyrin-G regulates spine neck width

Due to previous resolution limitations, proteins that affect neck morphology have not been extensively studied. Our GFPAnkG190 overexpression experiments show that ankyrin-G can alter spine neck width in addition to head size; when overexpressed in the spine head, only spine head area increased, however when overexpressed in the spine head and neck concurrently, head area increased even more and was accompanied by neck thickening. Spine neck changes have recently been shown to be a critical parameter of spine plasticity (Tonnesen et al. 2014) and it is emerging that spine necks are essential for myriad spine functions, including modulating AMPAR diffusion (Ashby et al., 2006; Kusters et al., 2013; Simon et al., 2014), compartmentalization of signalling (Grunditz et al., 2008; Murakoshi et al., 2011; Noguchi et al., 2005), and regulating diffusion across the neck during activity (Bloodgood and Sabatini, 2005). The presence of the leading psychiatric risk gene, ankyrin-G within the spine neck places it at a critical crossroads for influencing synaptic functions.

Ankyrin-G contributes to cLTP-dependent plasticity in spines

Knockdown of ankyrin-G impairs cLTP-dependent enlargement of spines, suggesting that ankyrin-G contributes to structural changes during cLTP. Neuronal activity caused accumulation of ankyrin-G in spines and SIM revealed that this was due to an increase in number, but not size, of ankyrin-G nanoclusters, indicating protein enrichment. Considering our data showing ankyrin-G overexpression in spines causes increased spine area, we propose that cLTP-dependent accumulation of ankyrin-G in spines is likely to play a key role in spine enlargement during synaptic plasticity. During this early stage of cLTP, rapid polymerization of actin and activation of CamKII occurs with specific proteins being trafficked into the spine, including AMPARs and actin remodelling proteins (Sala and Segal, 2014). This, combined with the location of ankyrin-G nanodomains at regulatory sites for plasticity (Cingolani and Goda, 2008), suggests that ankyrin-G may play a role in the modulation of cLTP. SIM showed that colocalization of ankyrin-G nanoclusters with GluA1 also increases after cLTP, indicative of increased participation in multiprotein complexes that may stabilize AMPARs at synapses. If ankyrin-G is an additional scaffold in the spine, it might be involved in localization and support of multiple membrane proteins including ion channels and NMDARs, which are essential for cLTP induction and expression. Further work will be required to dissect the exact role of ankyrin-G in this process. In support of our findings in cultured neurons, analysis of hippocampal lysates from mice that had undergone a learning task demonstrated significantly more ankyrin-G in the membrane and cytoskeletal fractions in trained mice. These data show that a physiological learning paradigm can cause relocation of a pool of ankyrin-G, supporting the validity of our cellular findings, and pointing to a mechanism involving ankyrin-G in learning and memory. This is also supported by recent data showing ankyrin-G knockdown in Drosophila causes short-term memory defects (Iqbal et al., 2013), and suggests that roles of ankyrin-G in learning and memory are worthy of further investigation.

Novel role for ankyrin-G 190kD isoform in synapse maintenance and plasticity

The longer isoforms of ankyrin-G have well-defined functions at the AIS and NoR (Rasband, 2010), however, our data indicate a role for 190kD ankyrin-G in the maintenance and function of mature cortical synapses. This isoform has been identified in PSDs (Nanavati et al., 2011), and our synaptoneurosome preparations corroborate an enrichment of this isoform at the synapse. GFPAnkG190 was enriched at postsynaptic sites, compared with GFPAnkG270, which was restricted to the AIS and SIM revealed that GFPAnkG190 overexpression yielded morphological changes in mushroom, but not thin spines. We show that knockdown of ankyrin-G in mature neurons caused reduced mEPSC amplitude and spine area. However, these effects on spines were rescued by RNAi-resistant AnkG190 but not AnkG270. Together, our overexpression and rescue experiments, and the enrichment of the 190kD ankyrin-G isoform in spines suggest that this isoform mediates morphological effects on dendritic spines.

Ankyrin-G and synaptic pathology in psychiatric disorders

Though linked to SZ, ASD and ID, ANK3 is most strongly linked to BD where glutamatergic synaptic pathology has been less extensively investigated. A previous study reported that 190kD ankyrin-G becomes specifically enriched in the PSD upon treatment with lithium, a common drug used to BD (Nanavati et al., 2011). We show that cLTP increases ankyrin-G in spines, in a similar manner to lithium treatment. Lithium has been shown to enhance LTP (Voytovych et al., 2012), suggesting that ankyrin-G in dendritic spines may be at the convergence between plasticity and therapeutic pathways relevant for BD. Our findings show that Ankyrin-G forms nanostructures within synapses, both in the spine neck and head. While spine size and density have been investigated, other parameters such as spine neck length and width could be relevant for pathogenesis as in an animal model of Rett syndrome (Belichenko et al., 2009). This stresses the importance of examining disease-relevant molecules at higher resolution to provide clues as to their specialized functions and role in pathogenesis. Human neuropathological studies using super-resolution microscopy would provide invaluable insight into pathogenesis. Our study suggests that understanding how subsynaptic phenotypes are modulated by molecular pathways, and how these phenotypes (including nanoscale localization of molecules) are affected in psychiatric disorders, may allow for more accurate mapping of disease-relevant genes and pathways onto specific elements of subcellular architecture.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture

Dissociated cultures of primary cortical neurons were prepared from E18 Sprague-Dawley rat embryos as described previously (Srivastava et al., 2012).

Immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy

Neurons were fixed, stained, imaged and quantified as previously described (Srivastava et al., 2012).

Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM) and analysis

Multichannel SIM images were acquired using a Nikon Structured Illumination super-resolution microscope using a 100× 1.4 NA objective and reconstructed using Nikon Elements software. Single plane or z-stack (z=0.2µm) images were processed and analyzed using Nikon Elements software, MetaMorph and ImageJ. Single spine analyses were carried out on ~100 spines across 5 neurons per condition.

Electrophysiology

Cultured cortical neurons were recorded in whole-cell configuration 3–4 days post-transfection (DIV24-25) as described previously (Srivastava et al., 2012).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by: R01MH071316, R01MH097216 to PP, R01NS071952 to GTS, R01MH078064 to JR and a Marie Curie Outgoing Postdoctoral Fellowship (#302281) to KRS. We are grateful to Bryan Copits and Claire Vernon for assistance with electrophysiology, Tristan Hedrick for help with brain slicing, Vann Bennett for the goat ankyrin-G Ab and Karen Zito, Jubao Duan and members of the Penzes lab for helpful discussions. We thank NU Nikon Cell Imaging Facility for use of the N-SIM and spinning-disc confocal and Teng Leong Chew, Constadina Arvanitis and Joshua Rappoport for assistance with imaging and analysis. All experiments involving animals were performed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of NU. KRS performed and analyzed confocal imaging, electrophysiological and some SIM experiments, led the project and wrote the paper. KJK performed SIM imaging, analysis and wrote the paper. JFP performed molecular biology. RG, BS and KM performed biochemistry. KL and JR performed behavioural and fractionation experiments. GTS supervised electrophysiology and advised on the project. PP supervised the project and wrote the paper.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashby MC, Maier SR, Nishimune A, Henley JM. Lateral diffusion drives constitutive exchange of AMPA receptors at dendritic spines and is regulated by spine morphology. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26:7046–7055. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1235-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bats C, Groc L, Choquet D. The interaction between Stargazin and PSD-95 regulates AMPA receptor surface trafficking. Neuron. 2007;53:719–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belichenko PV, Wright EE, Belichenko NP, Masliah E, Li HH, Mobley WC, Francke U. Widespread changes in dendritic and axonal morphology in Mecp2-mutant mouse models of Rett syndrome: evidence for disruption of neuronal networks. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2009;514:240–258. doi: 10.1002/cne.22009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett V, Healy J. Membrane domains based on ankyrin and spectrin associated with cell-cell interactions. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2009;1:a003012. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi C, Wu J, Jiang T, Liu Q, Cai W, Yu P, Cai T, Zhao M, Jiang YH, Sun ZS. Mutations of ANK3 identified by exome sequencing are associated with autism susceptibility. Human mutation. 2012;33:1635–1638. doi: 10.1002/humu.22174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpied TA, Kerr JM, Ehlers MD. Structural plasticity with preserved topology in the postsynaptic protein network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:12587–12592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711669105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom H, Ronnlund D, Scott L, Westin L, Widengren J, Aperia A, Brismar H. Spatial distribution of DARPP-32 in dendritic spines. PloS one. 2013;8:e75155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloodgood BL, Sabatini BL. Neuronal activity regulates diffusion across the neck of dendritic spines. Science. 2005;310:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.1114816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch M, Hayashi Y. Structural plasticity of dendritic spines. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2012;22:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Sabatini BL. Signaling in dendritic spines and spine microdomains. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2012;22:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HJ, Huang YH, Lau LF, Huganir RL. Regulation of the NMDA receptor complex and trafficking by activity-dependent phosphorylation of the NR2B subunit PDZ ligand. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24:10248–10259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0546-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani LA, Goda Y. Actin in action: the interplay between the actin cytoskeleton and synaptic efficacy. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9:344–356. doi: 10.1038/nrn2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MO, Husi H, Yu L, Brandon JM, Anderson CN, Blackstock WP, Choudhary JS, Grant SG. Molecular characterization and comparison of the components and multiprotein complexes in the postsynaptic proteome. Journal of neurochemistry. 2006;97(Suppl 1):16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deller T, Merten T, Roth SU, Mundel P, Frotscher M. Actin-associated protein synaptopodin in the rat hippocampal formation: localization in the spine neck and close association with the spine apparatus of principal neurons. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2000;418:164–181. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000306)418:2<164::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MA, O’Donovan MC, Meng YA, Jones IR, Ruderfer DM, Jones L, Fan J, Kirov G, Perlis RH, Green EK, et al. Collaborative genome-wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder. Nature genetics. 2008;40:1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/ng.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost NA, Shroff H, Kong H, Betzig E, Blanpied TA. Single-molecule discrimination of discrete perisynaptic and distributed sites of actin filament assembly within dendritic spines. Neuron. 2010;67:86–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SR, Iossifov I, Levy D, Ronemus M, Wigler M, Vitkup D. Rare de novo variants associated with autism implicate a large functional network of genes involved in formation and function of synapses. Neuron. 2011;70:898–907. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunditz A, Holbro N, Tian L, Zuo Y, Oertner TG. Spine neck plasticity controls postsynaptic calcium signals through electrical compartmentalization. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:13457–13466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2702-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson MG. Nonlinear structured-illumination microscopy: wide-field fluorescence imaging with theoretically unlimited resolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:13081–13086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406877102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Babcock H, Zhuang X. Breaking the diffraction barrier: super-resolution imaging of cells. Cell. 2010;143:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal Z, Vandeweyer G, van der Voet M, Waryah AM, Zahoor MY, Besseling JA, Roca LT, Vulto-van Silfhout AT, Nijhof B, Kramer JM, et al. Homozygous and heterozygous disruptions of ANK3: at the crossroads of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. Human molecular genetics. 2013;22:1960–1970. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan BA, Fernholz BD, Boussac M, Xu C, Grigorean G, Ziff EB, Neubert TA. Identification and verification of novel rodent postsynaptic density proteins. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2004;3:857–871. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400045-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr JM, Blanpied TA. Subsynaptic AMPA receptor distribution is acutely regulated by actin-driven reorganization of the postsynaptic density. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:658–673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2927-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizhatil K, Yoon W, Mohler PJ, Davis LH, Hoffman JA, Bennett V. Ankyrin-G and beta2-spectrin collaborate in biogenesis of lateral membrane of human bronchial epithelial cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:2029–2037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608921200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch I, Schwarz H, Beuchle D, Goellner B, Langegger M, Aberle H. Drosophila ankyrin 2 is required for synaptic stability. Neuron. 2008;58:210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusters R, Kapitein LC, Hoogenraad CC, Storm C. Shape-induced asymmetric diffusion in dendritic spines allows efficient synaptic AMPA receptor trapping. Biophysical journal. 2013;105:2743–2750. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Scannevin RH, Huganir R. Activation of silent synapses by rapid activity-dependent synaptic recruitment of AMPA receptors. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21:6008–6017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06008.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, Sawa A, Jaaro-Peled H. Better understanding of mechanisms of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: from human gene expression profiles to mouse models. Neurobiology of disease. 2012;45:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DT, Makino Y, Sharma K, Hayashi T, Neve R, Takamiya K, Huganir RL. Regulation of AMPA receptor extrasynaptic insertion by 4.1N, phosphorylation and palmitoylation. Nature neuroscience. 2009;12:879–887. doi: 10.1038/nn.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu HE, MacGillavry HD, Frost NA, Blanpied TA. Multiple Spatial and Kinetic Subpopulations of CaMKII in Spines and Dendrites as Resolved by Single-Molecule Tracking PALM. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014;34:7600–7610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4364-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGillavry HD, Kerr JM, Blanpied TA. Lateral organization of the postsynaptic density. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2011;48:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGillavry HD, Song Y, Raghavachari S, Blanpied TA. Nanoscale scaffolding domains within the postsynaptic density concentrate synaptic AMPA receptors. Neuron. 2013;78:615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino H, Malinow R. AMPA receptor incorporation into synapses during LTP: the role of lateral movement and exocytosis. Neuron. 2009;64:381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakoshi H, Wang H, Yasuda R. Local, persistent activation of Rho GTPases during plasticity of single dendritic spines. Nature. 2011;472:100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature09823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair D, Hosy E, Petersen JD, Constals A, Giannone G, Choquet D, Sibarita JB. Super-resolution imaging reveals that AMPA receptors inside synapses are dynamically organized in nanodomains regulated by PSD95. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:13204–13224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2381-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanavati D, Austin DR, Catapano LA, Luckenbaugh DA, Dosemeci A, Manji HK, Chen G, Markey SP. The effects of chronic treatment with mood stabilizers on the rat hippocampal post-synaptic density proteome. Journal of neurochemistry. 2011;119:617–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07424.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor MW, Cai X, Stone MR, Bloch RJ, Thompson SM. The actin binding domain of betaI-spectrin regulates the morphological and functional dynamics of dendritic spines. PloS one. 2011;6:e16197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi J, Matsuzaki M, Ellis-Davies GC, Kasai H. Spine-neck geometry determines NMDA receptor-dependent Ca2+ signaling in dendrites. Neuron. 2005;46:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger JI, Jr, Koller DL, Jung J, Edenberg HJ, Foroud T, Guella I, Vawter MP, Kelsoe JR, and for the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Bipolar G. Identification of Pathways for Bipolar Disorder: A Meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Buonanno A, Passafaro M, Sala C, Sweet RA. Developmental vulnerability of synapses and circuits associated with neuropsychiatric disorders. Journal of neurochemistry. 2013;126:165–182. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Cahill ME, Jones KA, VanLeeuwen JE, Woolfrey KM. Dendritic spine pathology in neuropsychiatric disorders. Nature neuroscience. 2011;14:285–293. doi: 10.1038/nn.2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pielage J, Cheng L, Fetter RD, Carlton PM, Sedat JW, Davis GW. A presynaptic giant ankyrin stabilizes the NMJ through regulation of presynaptic microtubules and transsynaptic cell adhesion. Neuron. 2008;58:195–209. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pielage J, Fetter RD, Davis GW. A postsynaptic spectrin scaffold defines active zone size, spacing, and efficacy at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. The Journal of cell biology. 2006;175:491–503. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200607036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell SM, Moran JL, Fromer M, Ruderfer D, Solovieff N, Roussos P, O’Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Bergen SE, Kahler A, et al. A polygenic burden of rare disruptive mutations in schizophrenia. Nature. 2014;506:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature12975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband MN. The axon initial segment and the maintenance of neuronal polarity. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:552–562. doi: 10.1038/nrn2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala C, Segal M. Dendritic spines: the locus of structural and functional plasticity. Physiological reviews. 2014;94:141–188. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze TG, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Akula N, Gupta A, Kassem L, Steele J, Pearl J, Strohmaier J, Breuer R, Schwarz M, et al. Two variants in Ankyrin 3 (ANK3) are independent genetic risk factors for bipolar disorder. Molecular psychiatry. 2009;14:487–491. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon CM, Hepburn I, Chen W, De Schutter E. The role of dendritic spine morphology in the compartmentalization and delivery of surface receptors. Journal of computational neuroscience. 2014;36:483–497. doi: 10.1007/s10827-013-0482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava DP, Copits BA, Xie Z, Huda R, Jones KA, Mukherji S, Cahill ME, VanLeeuwen JE, Woolfrey KM, Rafalovich I, et al. Afadin is required for maintenance of dendritic structure and excitatory tone. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:35964–35974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.363358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada T, Simonetta A, Batterton M, Kinoshita M, Edbauer D, Sheng M. Role of Septin cytoskeleton in spine morphogenesis and dendrite development in neurons. Current biology : CB. 2007;17:1752–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonnesen J, Katona G, Rozsa B, Nagerl UV. Spine neck plasticity regulates compartmentalization of synapses. Nature neuroscience. 2014;17:678–685. doi: 10.1038/nn.3682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonnesen J, Nagerl UV. Superresolution imaging for neuroscience. Experimental neurology. 2013;242:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursitti JA, Martin L, Resneck WG, Chaney T, Zielke C, Alger BE, Bloch RJ. Spectrins in developing rat hippocampal cells. Brain research Developmental brain research. 2001;129:81–93. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voytovych H, Krivanekova L, Ziemann U. Lithium: a switch from LTD- to LTP-like plasticity in human cortex. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Srivastava DP, Photowala H, Kai L, Cahill ME, Woolfrey KM, Shum CY, Surmeier DJ, Penzes P. Kalirin-7 controls activity-dependent structural and functional plasticity of dendritic spines. Neuron. 2007;56:640–656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Bennett V. Restriction of 480/270-kD ankyrin G to axon proximal segments requires multiple ankyrin G-specific domains. The Journal of cell biology. 1998;142:1571–1581. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.