Abstract

Family-to-family services are emerging as an important adjunctive service to traditional mental health care and a vehicle for improving parent engagement and service use in children’s mental health services. In New York State, a growing workforce of Family Peer Advocates (FPA) is delivering family-to-family services. We describe the development and evaluation of a professional program to enhance Family Peer Advocate professional skills, called the Parent Engagement and Empowerment Program (PEP). We detail the history and content of PEP and provide data from a pre/post and 6-month follow up evaluation of 58 FPA who participated in the first Statewide regional training effort. Self-efficacy, empowerment, and skills development were assessed at 3 time points: baseline, post-training, and 6-month follow-up. The largest changes were in self-efficacy and empowerment. Regional differences suggest differences in Family Peer Advocate workforce across areas of the state. This evaluation also provides the first systematic documentation of Family Peer Advocate activities over a six-month period. Consistent with peer specialists within the adult health care field, FPA in the children’s mental health field primarily focused on providing emotional support and service access issues. Implications for expanding family-to-family services and integrating it more broadly into provider organizations are described.

Keywords: Family Peer Advocates, Children’s mental health, Parent engagement and empowerment, Family support services

Introduction

Despite dramatic advances in the identification and treatment of children’s mental illness, high levels of unmet need persist in the children’s mental health system (U. S. Department of Health, Human Services 1999, 2000, 2001). Decades of studies have identified numerous family level barriers to treatment participation including socio-economic status, racial and ethnic variations (Kataoka et al. 2003; Garland et al. 2003); insufficient insurance coverage (Diala et al. 2000; Kataoka et al. 2003; Mechanic et al. 2002; Pumariega et al. 1998); and provider-related obstacles such as lengthy waiting lists (Chow et al. 2003; Fortney et al. 1999; Hines-Martin et al. 2003). Research suggests that urban minority families living in poverty are confronted with more obstacles to help seeking, including lack of knowledge about services (McKay and Bannon 2004), stigma, distrust of professionals, and lack of social support (Hoagwood 2005; Owens et al.2002; McKay and Bannon 2004; Nickerson et al. 1994; Tolan et al. 2002; Whaley 2001).

Innovative service approaches that capitalize on the experience and credibility of peer parents as service connectors have been developed in the past two decades. For example, Koroloff and Friesen (1997) developed one of the first family-to-family programs to reduce barriers to services for low-income children and families. The program involved the use of Family Associates, parents of children with special needs, who provided information, emotional support, and tangible assistance. Results of a comparative evaluation suggested that families were more likely to make and keep a first appointment at the mental health clinic if they had received supportive services from the family associate. Additionally, these families scored significantly higher than families in the comparison group on subscales of the family empowerment scale, although the differences were modest. However, the addition of a family associate did not affect ongoing attendance at clinic appointments, which was attributed to barriers that the associates could not help to overcome, such as those related to the family situation or the mental health service system.

In a rigorous study of a program targeted at improving parent self-efficacy called the Vanderbilt Family Empowerment Project (Bickman et al. 1998), caregivers of children with serious emotional needs participated in a 11-hour curriculum to enhance skills in navigating the mental health system. This study, embedded in the Fort Bragg Child and Adolescent Mental Health Demonstration (Bickman et al. 1998), involved 250 military families who were primarily Caucasian (73%) mothers (82%). The program was delivered jointly by a mental health professional and a parent advocate and focused on knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy. Results indicated significant increases in knowledge about mental health services and in service self-efficacy among the intervention group; these effects were maintained 9 months later. However, there was no effect on caregiver service use or children’s mental health status.

A recent review of the literature on family support services, including those delivered by parents, clinicians, or teams, found that similar core components (i.e., information, instructional skill development, emotional support, advocacy) exist across all types of providers (Hoagwood et al. 2010). In addition, more than a dozen effective family support programs are available and have been rigorously examined. However, the research base on family-to-family or team-based approaches, despite common core elements, remains thin. Clinician-led models tended to focus on parent skill building to manage the child’s symptoms. When the parents’ own needs were addressed, they were in the service of increasing the parents’ capacity to support the child’s compliance with treatment (e.g., help parent manage own anxiety so parent can support child adherence to exposure exercises). By contrast, family-led models tended to focus on building skills to increase parents’ personal coping skills, respite, and self-care. In addition, they were unique in providing advocacy supports and were more apt to recognize and discuss system level barriers than parent level barriers to service access/participation. Team-based models tended to be more balanced, reflecting the expertise of the different types of providers.

Addressing Barriers in Children’s Mental Health

To take advantage of an experienced and active group of Family Peer Advocates (FPA) in New York, the NYS Office of Mental Health (NYSOMH) has invested substantial resources ($17 M/year) to promote collaboration between FPA and clinicians. An active consortium of family support and mental health advocacy organizations (e.g., the NYS Chapter of the Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health (FFCMH), Mental Health America of NYC, Families on the Move, and, more recently, NAMI), in partnership with OMH and Columbia University are professionalizing the work of FPA. This includes the development of a credential for FPA that entails professional training. It also includes development of an outcome monitoring system and of a fiscal platform to enable family-to-family support services to be billable. In conjunction with a major overhaul of the operational capacity of child serving clinics in NYS, OMH anticipates increasing the number of FPA over the next 2 years. This is the context in which the Parent Engagement and Empowerment Program (PEP) has been developed.

Background on the Development of the PEP

In 1993, a group of FPA from Mental Health America of NYC and policy makers from NYSOMH and NYC formed a workgroup to address barriers to parent access to mental health services. The workgroup suggested including experienced peer parents as family advocates to work directly with parents to improve children’s access into services. In 2002, the workgroup broadened to include researchers from Columbia University (Jensen, Hoagwood) and Mount Sinai (McKay), and the group began the development of a professional training and consultation program for FPA. Modeled on the Fort Bragg family empowerment program (Bickman et al. 1998), an iterative development process evolved including experienced family advocates, state and city policy leaders, and researchers. The result was the development of the Parent Engagement and Empowerment Program (PEP). Integrating grassroots principles of family support and available scientific theories on behavior change, the conceptual framework, training/consultation model, and content were developed. A detailed description of the current PEP conceptual framework is available elsewhere (Olin et al. 2010a, b). The remainder of this paper describes the training/consultation approach, curriculum content, and evaluation data from the first statewide training of this model.

PEP: The Training and Consultation Model

An important but unique feature of PEP is that the training and consultation is co-led by a FPA and a mental health clinical provider. A key ingredient is the collaborative partnership embodied by the co-leaders, who reflect and model the respectful communication of individuals with differing perspectives but a common goal, namely, to improve the mental health care of children and families. This collaborative relationship entails respecting and integrating competing perspectives. For example, mental health professionals who work with children are trained to see the child as their primary client, while for FPA, a parent or the entire family is seen as the focus. Over and above differences in perspectives, there are inherent differences in professional backgrounds and experience that may impact the relationship between FPA and clinical co-trainers. Clinical partners are often viewed as highly trained professionals with clinical expertise, and FPA are often viewed as paraprofessionals with limited knowledge and skills. These perceptions often mirror and can perpetuate the stereotypes that already exist in clinical practice. Thus the goal of the PEP training partnership approach is to model the type of collaborative relationship that respects and values the unique contribution of each expert partner while demonstrating constructive dialogues and negotiation when differences arise. In order to promote the development of a collaborative relationship between clinical and family partners, co-trainers prepare for training sessions and debrief each training session together.

The core training is delivered over 40-hours and training goals are achieved through methods based on adult learning, including direct instruction to share knowledge or techniques for practice, group support, modeling, vicarious learning, and practice opportunities (primarily through role rehearsals) with feedback. Bi-weekly consultation calls for 6 months follow the core training to consolidate skills as they are applied by the FPA in their work with parents. The core training is divided into the following seven sections:

Conceptual Framework

This module describes the overarching framework of PEP, which seeks to connect the principles of parent support with social learning theory about behavior activation (Jaccard et al. 2002). The Unified Theory of Behavior (UTB), developed by Jaccard et al. (2002) and applied to PEP, has been described in depth by Olin et al. (2010a, b). Briefly, UTB posits that behavioral activation is a function of proximal determinants of behavior and equally critical attitudinal determinants that affects one’s intention to act. Immediate proximal determinants of behavior include factors such as knowledge and skills, environmental obstacles, the immediate salience of the action or the presence of competing habits or automatic processes. Behavioral intention is influenced by a host of internal processes such as the expected value of the action, social norms, attitudes and beliefs, emotions and affect, and self-efficacy beliefs. In the PEP conceptual framework, the principles of parent support drive the goals, objectives and actions that are targeted by FPA, while behavior activation theory informs understanding of the critical determinants of achieving stated goals.

The remaining sections of the curriculum focus on core processes involved in working directly with parents and on mental health content knowledge. Core process areas include: Listening, Engagement, and Boundary Setting Skills, which covers basic active listening skills, more global strategies for building rapport with families, and constructive sharing of personal experiences through self-disclosure, while maintaining professional boundaries. The module builds heavily on prior research outlining effective strategies to increase initial involvement and ongoing retention in children’s mental health services (e.g. McKay et al. 1996, 1998). Priority Setting, Developing an Action Plan, and Problem Solving focuses on teaching advocates ways to assess and determine parents’ needs in order to develop specific goals and action plans. Based on the PEP conceptual framework, FPA learn how to systematically identify potential obstacles and problem solve around barriers to increase parent success towards goals and objectives. Group Management Skills provides basic information on group development (Tuckman and Jensen1977), group management skills and group facilitation.

Core content areas provide basic information on mental illness and on the varied systems in which children and families may be involved. The Mental Health System: Preparing Parents to Navigate the System provides an overview of the array of services available in children’s mental health (e.g., outpatient and inpatient care, emergency services, and community supports), and provides practical tips to prepare parents to navigate this complex system. Specific Disorders and Their Treatment provides a basic knowledge of the diagnostic process in children, common child mental health problems, evidence-based treatments, as well as the implications of diagnostic labels for the child, the family, and service access. The module on Service Options through the School System provides basic information about parents’ rights and responsibilities within the educational system, tips on how to partner effectively with teachers and other school staff, as well as ways to access necessary resources or services to support their child’s academic achievement.

The core training, involving these seven sections, takes approximately 40 hours. This is followed by bi-weekly one-hour consultation calls for 6 months (12 hours total) to support FPA skill acquisition and application in their direct work with parents. The consultation is also co-led by the family advocate and clinical partner trainers. FPA use the calls to present challenging cases for consultation and feedback from trainers and their peers; the PEP conceptual framework, applying UTB activation strategies, guides the consultation.

From 2007 to 2009, the NYSOMH and NYS Department of Education requested that Columbia University conduct statewide training of 58 FPA using the full 40-hour training and 6-month consultation model. To evaluate its preliminary impact on beliefs (self-efficacy, empowerment), skills, and overall satisfaction with the program, we conducted a pre-post evaluation with 6-month follow-up of these training. The methods and results are described below.

Methods

Participants

Fifty-eight FPA from three regions volunteered to participate in the training. The three regions were Long Island (n = 14), Central NYS (n = 22) and Western NYS (n = 22). There was no comparison group for training and all data collected from FPA was anonymous.

Measures

Collaborative Skills

Pre, post and 6-month assessments examining development of collaborative skills were assessed. The measure was a 36 item scale keyed to training content and rated on a scale of 1 (Disagree) to 4 (Agree). Six subscales were included, one for each module: (1) Listening, Engagement, and Boundary Settings Skills, (2) Group Management, (3) Priority Setting, (4) Specific Disorders and Their Treatment, (5) Mental Health Services, and (6) School Options. Questions included, “I can talk to parents about our mutual responsibilities in the working relationship” and “I am aware of barriers that parents may face in seeking help for their children and know how to help them overcome those barriers.” Alpha reliability ranged from .77 (Listening, Engagement, and Boundary Setting) to .93 (Specific Disorders and Their Treatment).

Self-Efficacy and Empowerment

Pre, post and 6-month assessments of self-efficacy and empowerment were conducted. The Vanderbilt Mental Health Services Efficacy (VMHSE) scale (Bickman et al.1991) was modified to measure the degree to which FPA feel effective in accessing and mental health services for the families they work with. Items are scored on a five-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Typical items include, “I believe that I can help parents access and use effectively mental health services for their children” and “My skills in dealing with mental health services will help me to empower parents to change things that might be wrong with their child’s treatment.” Alpha reliability for the VMHSE was .89.

The Family Empowerment Scale (FES) (Koren et al. 1992) assesses parent/caregiver perceptions and attitudes about their roles and responsibilities within their local service systems and their ability to advocate on behalf of their child. It was modified for use in this evaluation, to measure FPA perceptions. Items are scored on a 5-point likert type scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very often). The FES assesses three domains of FPA empowerment, Work (e.g. “I know what to do when problems arise with the families with whom I work”), Children services (e.g., “I make sure that professionals understand parent/caregivers’ opinions about what services their children need”), and Community (e.g. “I feel I can have a part in improving services for children in my community”). Alpha reliability for the Family Empowerment Scale was .94.

FPA Activities

FPA activities, particularly those emphasized within PEP training, were measured three times during the 6-month phone consultation phase at 2, 4 and 6 months. These activities were divided into categories based primarily on the categories of family support identified in a recent review paper (Hoagwood et al. 2010). Using this 27-item checklist (see Table 3 in Results section below), FPA were asked to choose a parent with whom they work and report on activities engaged with that parent. FPA activities were categorized according to: (1) Emotional Support; (2) Action Planning; (3) Information Provision; (4) Advocacy; and (5) Skill Development. FPA were instructed to endorse an item only if they did engage in the activity with the caregiver over the past 2 months.

Table 3.

Family Peer Advocate service activities reported

| % endorsed at 2 months |

% endorsed at 4 months |

% endorsed at 6 months |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

N = 49 (T1) |

N = 46 (T2) |

N = 51 (T3) |

|

| Emotional support | |||

| I spent time listening to the parents’ concerns and building relationship with parents (Q2) |

93 | 95 | 91 |

| I helped this parent identify ways to take care of him/herself (Q18) | 76 | 64 | 61 |

| Action planning | |||

| I clearly stated the purpose of the meeting (Q1) | 60 | 64 | 70 |

| I spent time setting priorities with the parent (Q3) | 59 | 69 | 69 |

| I made a list of concerns and prioritized them (Q5) | 68 | 83 | 85 |

| I made specific recommendations that were clear and realistic (Q6). | 72 | 76 | 67 |

| I followed up with parent on a previous goal (Q7) | 73 | 75 | 67 |

| Information provision | |||

| I provided information and resources to parents about services they are seeking (Q17) |

73 | 70 | 77 |

| I provided the parent with information about their child’s specific disorder (Q19) |

63 | 50 | 63 |

| I provided information to parent about how to access mental health services that are best for his/her child (Q24) |

62 | 75 | 69 |

| Advocacy | |||

| I provide parent with information about his/her rights (Q27) | 71 | 71 | 73 |

| I worked with parent to facilitate a contact with a teacher (Q8) | 74 | 39 | 49 |

| I accompanied parent to an appointment with a teacher (Q12) | 43 | 39 | 47 |

| I worked with parent to facilitate a contact with a guidance counselor/school social worker (Q9) |

46 | 50 | 53 |

| I accompanied parent to an appointment with a guidance counselor/school social worker (Q13) |

39 | 62 | 55 |

| I accompanied a parent to an IEP meeting (Q25) | 70 | 63 | 77 |

| I worked with parent to facilitate a contact with a mental health professional (psychologist) (Q11) |

59 | 48 | 48 |

| I accompanied parent to an appointment with a other mental health professional (psychologist) (Q15) |

53 | 50 | 57 |

| I worked with parent to facilitate a contact with a medical professional (Q10) |

48 | 55 | 52 |

| I accompanied parent to an appointment with a medical professional (psychiatrist) (Q14) |

43 | 56 | 62 |

| Skill development | |||

| I helped parent create a case management book (Q4) | 32 | 42 | 39 |

| I helped to prepare parent for an appointment with a professional (Q16) |

66 | 71 | 75 |

| I helped prepare the parent for his/her IEP meeting (Q26) | 72 | 61 | 66 |

| I role played with parent about talking with a teacher about their child’s behavior (Q20) |

35 | 39 | 50 |

| I role played with parent about talking with a guidance counselor/school social worker about their child’s behavior (Q21) |

35 | 41 | 45 |

| I role played with parent about talking with a medical professional (psychiatrist) about their child’s behavior (Q22) |

35 | 50 | 55 |

| I role played with parent about talking with another mental health professional (psychologist) about their child’s behavior (Q23) |

31 | 47 | 28 |

Results

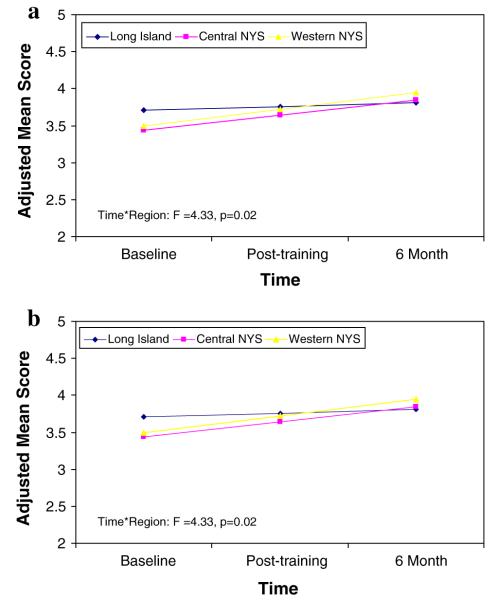

The means and standard deviations for collaborative skills, family empowerment and services self-efficacy are summarized across time points (baseline, post training and 6 month follow-up) by region in Table 1. Across three regions, increases in family empowerment, mental health services efficacy, and self-assessment of skills were seen over time (see Table 2; all p-values < 0.05). In addition, a series of repeated measures ANOVAs showed significant region differences on engagement and group management scales from baseline to post-training to 6-month follow-up (F(2,49) = 3.62, p = 0.03 for engagement scale; F(2, 49) = 4.33, p = 0.02 for group management scale). As seen in Fig. 1a and 1b, greater improvements on engagement and group management scores were seen in Central and Western NYS than in Long Island over three time points. Notably, the group of Long Island FPA had higher baseline scores on many of the collaborative skills measures, compared to the other two regions. No significant region by time interaction was found on any of the mental health services efficacy and family empowerment scales.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations [M(sD)] for all measures across time points by regions

| Region 1 |

Region 2 |

Region 3 |

All regions |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base-line | Post-training | 6 month | Base-line | Post-training | 6 month | Base-line | Post-training | 6 month | Base-line | Post-training | 6 month | |

| N = 14 | N = 14 | N = 14 | N = 22 | N = 20 | N = 20 | N = 22 | N = 22 | N = 19 | N = 58 | N = 56 | N = 53 | |

| Collaborative skills | ||||||||||||

| Engagement, listening | 3.67 (0.35) | 3.80 (0.24) | 3.76 (0.33) | 3.39 (0.51) | 3.75 (0.37) | 3.77 (0.26) | 3.39 (0.43) | 3.91 (0.15) | 3.83 (0.24) | 3.46 (0.45) | 3.83 (0.27) | 3.79 (0.27) |

| Group management | 3.70 (0.31) | 3.74 (0.32) | 3.80 (0.25) | 3.19 (0.68) | 3.77 (0.34) | 3.74 (0.34) | 3.22 (0.53) | 3.92 (0.12) | 3.80 (0.25) | 3.32 (0.59) | 3.82 (0.28) | 3.78 (0.28) |

| Priority setting | 3.34 (0.46) | 3.55 (0.44) | 3.54 (0.41) | 3.08 (0.70) | 3.78 (0.35) | 3.71 (0.25) | 3.15 (0.60) | 3.73 (0.41) | 3.55 (0.39) | 3.17 (0.61) | 3.70 (0.40) | 3.61 (0.35) |

| Specific disorders | 3.17 (0.71) | 3.73 (0.44) | 3.56 (0.45) | 3.11 (0.73) | 3.91 (0.20) | 3.80 (0.35) | 2.59 (0.79) | 3.69 (0.50) | 3.44 (0.72) | 2.93 (0.78) | 3.78 (0.40) | 3.61 (0.55) |

| MH system | 3.27 (0.40) | 3.54 (0.47) | 3.65 (0.33) | 3.11 (0.73) | 3.58 (0.52) | 3.69 (0.39) | 2.98 (0.61) | 3.70 (0.35) | 3.57 (0.45) | 3.10 (0.62) | 3.62 (0.44) | 3.63 (0.39) |

| School services | 3.34 (0.58) | 3.68 (0.36) | 3.69 (0.42) | 3.17 (0.81) | 3.76 (0.46) | 3.74 (0.52) | 3.23 (0.66) | 3.84 (0.26) | 3.67 (0.43) | 3.23 (0.66) | 3.77 (0.37) | 3.70 (0.46) |

| Family empowerment | ||||||||||||

| Work | 4.03 (0.51) | 4.23 (0.48) | 4.14 (0.54) | 3.95 (0.43) | 4.36 (0.43) | 4.36 (0.36) | 3.86 (0.29) | 4.29 (0.51) | 4.16 (0.46) | 3.93 (0.40) | 4.30 (0.47) | 4.23 (0.45) |

| Services | 3.60 (0.68) | 3.81 (0.75) | 3.51 (0.71) | 3.80 (0.66) | 4.22 (0.58) | 4.12 (0.56) | 3.70 (0.43) | 4.00 (0.69) | 3.93 (0.78) | 3.71 (0.58) | 4.03 (0.68) | 3.88 (0.72) |

| Community | 3.63 (0.58) | 3.89 (0.60) | 3.81 (0.65) | 3.73 (0.68) | 4.20 (0.64) | 4.00 (0.62) | 3.74 (0.62) | 3.98 (0.75) | 4.04 (0.80) | 3.71 (0.62) | 4.04 (0.68) | 3.96 (0.69) |

| Mental health services self efficacy |

3.70 (0.52) | 3.73 (0.54) | 3.69 (0.46) | 3.60 (0.43) | 3.79 (0.52) | 3.87 (0.35) | 3.73 (0.30) | 3.98 (0.39) | 3.85 (0.45) | 3.68 (0.41) | 3.85 (0.48) | 3.82 (0.41) |

Table 2.

Effects of region and time on all measures

| Variable and source | F | p |

|---|---|---|

| Collaborative skills | ||

| Engagement, listening | ||

| Timea | 30.13 | <0.0001 |

| Regionb | 3.81 | 0.03 |

| Time*regionc | 3.62 | 0.03 |

| Group management | ||

| Timea | 34.38 | <0.0001 |

| Regionb | 5.64 | 0.01 |

| Time*regionc | 4.33 | 0.02 |

| Priority setting | ||

| Timea | 28.87 | <0.0001 |

| Regionb | 1.54 | 0.22 |

| Time*regionc | 2.5 | 0.09 |

| Specific disorders | ||

| Timea | 42.41 | <0.0001 |

| Regionb | 3.48 | 0.04 |

| Time*regionc | 1.89 | 0.16 |

| MH system | ||

| Timea | 48.03 | <0.0001 |

| Regionb | 0.84 | 0.44 |

| Time*regionc | 0.74 | 0.48 |

| School services | ||

| Timea | 32.75 | <0.0001 |

| Regionb | 0.69 | 0.5 |

| Time*regionc | 0.8 | 0.46 |

| Family empowerment | ||

| Work | ||

| Timea | 22.74 | <0.0001 |

| Regionb | 1 | 0.37 |

| Time*regionc | 2.01 | 0.14 |

| Services | ||

| Timea | 5.47 | 0.02 |

| Regionb | 0.04 | 0.96 |

| Time*regionc | 1.5 | 0.23 |

| Community | ||

| Timea | 16.19 | 0.0002 |

| Regionb | 0.11 | 0.9 |

| Time*regionc | 0.16 | 0.85 |

| Mental health services self efficacy | ||

| Timea | 7.02 | 0.01 |

| Regionb | 1.08 | 0.35 |

| Time*regionc | 1.56 | 0.22 |

df = (1,49)

df = (2,49)

df = (2,49)

Fig. 1.

a. Change of group management scores across time. b. Change of engagement scores across time

Table 3 shows the percentage of FPA who endorsed specific activities related to five categories of Family Support across three time points: Emotional Support, Action Planning, Information Provision, Advocacy and Skill Development. The most commonly reported category related to Emotional Support, where over 90% of FPA consistently reported spending time listening and building relationship with the caregivers they work with. Activities related to Action Planning, Information Provision and Advocacy were reported by approximately two-thirds of FPA. Within the Action Planning category, FPA activities endorsed with increasing frequency over time were those emphasized within the PEP training, such as priority setting (68% at T1–85% at T3) and being clear about meeting purpose with parents (60% at T1 and 70% at T3). Information Provision activities related primarily to service and resource access and these increased over time (e.g., 62% at T1, 75% at T2 and 69% at T3), with over two-thirds of FPA continuing to address service access issues even after 6 months of working with a parent. Advocacy-related activities remained fairly consistent over time, particularly those related to the education system. Initially, educational advocacy appeared to focus around teacher contact and this decreased over time (75% at T1 and 49% by T3). The most frequently endorsed activity within the Skill Development category related to preparing parents to meet with professionals or for IEP meetings; role plays, were much less frequently endorsed by FPAs, though FPA reported increased use of such strategies over time, so that approximately half were using role plays to develop parent’s skills by the 6-month time point.

Discussion

Results of this first evaluation of statewide PEP training indicate FPA-reported changes in skills, self-efficacy and empowerment. These changes are consistent with an earlier pilot PEP training of FPA within New York City (Olin et al. in press). In this evaluation, changes were noted from baseline to post-training, with changes sustained across the consultation period at 6-month follow-up. In particular, regional differences were noted for collaborative skills related to Engagement and Group Management, suggesting regional differences in the caliber of FPA. Post training discussions among PEP trainers indicated that Region 1 FPA who participated in the training were generally more experienced professional peers, as evidenced by higher baseline scores on many of the study measures.

Importantly, this evaluation provides the first systematically collected information about FPA activities over time. Emotional support and service access issues, especially involving the education system, appear to be a key focus of FPA and parent interactions, consistent with anecdotal reports by FPA statewide and a recent national survey of certified peer specialists (Salzer et al. 2010). Thus, beyond self-perception of skill improvement, these FPA who participated in PEP training reported increase in use of specific PEP skills such as priority setting and using role-plays to help develop parent skills. Interestingly, FPA activities associated with providing parents support around service access continued to increase (rather than decrease) over time, suggesting perhaps system-level or family situational issues that were not readily overcome by FPA alone.

Limitations

This evaluation has several important limitations. First, this data were collected as part of a statewide initiative rather than as part of a research project; the rapid roll out resulted in a missed opportunity to collect key FPA data that would be important to help contextualize these findings. No data was collected on the participating FPAs’ background, work experience, and work settings in which they operate. Given our past work with this emerging workforce (Olin et al. 2010a, b) and a recent national survey of a similar workforce in the adult area (Salzer et al. 2010), variability of FPA work functions and settings is significant. Given our findings of regional differences across the state, key FPA data pertaining to their background, work experience and context, would be important to better understand findings from this evaluation. Current state evaluations of PEP training have begun to collect such data, which can be used to better focus future training efforts as the state moves toward certification of this emerging workforce.

Second, the list of FPA activities examined in this evaluation is not exhaustive and does not fully capture the range of activities FPAs engage in within the community. Prior studies within New York City noted that many FPAs often engage in activities beyond the scope of their job descriptions (Roussos et al. 2008). Thus, the reported activities captured here only pertain to those addressed as part of PEP training, and cannot be contextualized within the wider range of activities FPAs may engage in within their work setting. Additionally, how representative FPA reports of their activities based on their work with one family is unclear. However, the aggregate data of the most common FPA activities is validated by anecdotal reports and national survey.

Third, typical to evaluation efforts, the data here represents self-report which is a serious limitation, particularly as it pertains to skill assessment. Reported changes may simply reflect FPA satisfaction with training. However these changes in FPA report on skills and activity over time suggest that a more rigorous evaluation (e.g., including a comparison group) of this PEP training model is worthwhile.

Fourth, this evaluation of PEP training did not extend to the impact of FPA services. However, as noted by Salzer et al. (2010), building an evidence base on the effectiveness of peer-to-peer delivered services must take into consideration the variety settings and activities FPAs engage in. Outcomes examined must take into account such variation. A reasonable and realistic strategy to examine the impact of FPA services continues to be a topic of discussion within the field.

Future Directions

Based on this first statewide PEP training initiative, the PEP training has been revised to better address several key issues, including a training model that can engage a workforce with highly varied backgrounds and work experience. For example, PEP now includes a clearer conceptual framework, with an integration of the Unified Theory of Behavior (UTB) with Principles of Parent Support (see Olin et al. 2010a, b). Additionally, role plays–consistently, the most highly rated activity–have also been substantially revised to maximize FPA skill development.

Current research on peer-delivered services within children’s mental health involves attention to two separate but complementary areas. One is the process and content of the specific services delivered by FPA trained in PEP, with the goal of developing quality indicators by which to benchmark and standardize effective delivery. The second research area focuses on the social-organizational processes within agencies that facilitate or inhibit delivery of family-to-family services by FPA. The goal is to promote the integration of FPA services into clinical mental health treatment. Advancing science on family advocacy is likely to be a key area for research and practice in children’s mental health and may prove to be the most powerful tool for effecting sustainable quality improvements in children’s mental health systems.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Belinda Ramos, Maura Crowe, Sudha Mehta, Theresa Schwartz and Marlene Penn for their helpful input on this project.

Contributor Information

James Rodriguez, New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

S. S. Olin, Division of Mental Health Services & Policy Research, Columbia University, 100 Haven Avenue, Suite 31D, New York, NY 10032, USA; New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Kimberly E. Hoagwood, New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Sa Shen, New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Geraldine Burton, New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Marleen Radigan, New York State Office of Mental Health, Albany, NY, USA.

Peter S. Jensen, The REACH Institute, New York, NY, USA

References

- Bickman LB, Earls L, Klindworth L. Mental health services efficacy scale. Vanderbilt Center for Mental Health Policy; Nashville, TN: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Heflinger CA, Northrup D, Sonnichsen S, Schilling S. Long term outcomes to family caregiver empowerment. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1998;7:269–282. doi:10.1023/A:1022937327049. [Google Scholar]

- Chow J, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:792–797. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.792. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diala C, Muntaner C, Walrath C, Nickerson K, LaVeist T, Leaf PJ. Racial differences in attitudes toward professional mental health care and in the use of services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:455–464. doi: 10.1037/h0087736. doi:10.1037/h0087736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortney J, Rost K, Zhang M, Warren J. The impact of geographic accessibility on the intensity and quality of depression treatment. Medical Care. 1999;37:884–893. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Landsverk JA, Lau AS. Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use among children in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2003;5:491–507. doi: 10.1016/S0190-7409(03)00032-X. [Google Scholar]

- Hines-Martin V, Brown-Piper A, Kim S, Malone M. Enabling factors of mental health service use among African Americans. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2003;17:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(03)00094-3. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9417(03)00094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood KE. Family-based services in children’s mental health: A research review and synthesis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:690–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01451.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood KE, Cavaleri M, Olin SS, Burns BJ, Slaton E, Gruttadaro JD, et al. Family support in children’s mental health: A review and synthesis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2010;13:1–45. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0060-5. doi:10.1007/s10567-009-0060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dodge T, Dittus P. Parent-adolescent communication about sex and birth control: A conceptual framework. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2002;97:9–41. doi: 10.1002/cd.48. doi:10.1002/cd.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Laycox LH, Wong M, Escudero P, Wenli T, et al. A school-based mental health program for traumatized Latino immigrant children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:311–318. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00011. doi:10.1097/01.CHI.0000037038.04952.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren PE, DeChillo N, Friesen BJ. Measuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disabilities: A brief questionnaire. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1992;37:305–321. doi:10.1037/h0079106. [Google Scholar]

- Koroloff NM, Friesen BJ. Challenges in conducting family-centered mental health services research. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 1997;5:130–137. doi: 10.1177/106342669700500301. [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Bannon WM. Engaging families in child mental health services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;13:905–921. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, McCadam K, Gonzales JJ. Addressing the barriers to mental health services for inner city children and their caretakers. Community Mental Health Journal. 1996;32:353–361. doi: 10.1007/BF02249453. doi: 10.1007/BF02249453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Stoewe J, McCadam K, Gonzales J. Increasing access to child mental health services for urban children and their care givers. Health and Social Work. 1998;23:9–15. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D, Bilder S, McAlpine DD. Employing persons with serious mental illness. Health Affairs. 2002;21:242–253. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.242. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson KJ, Helms JE, Terrell F. Cultural mistrust, opinions about mental illness, and black students’ attitudes toward seeking psychological help from white counselors. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1994;41:378–385. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.41.3.378. [Google Scholar]

- Olin SS, Hoagwood KE, Rodriguez J, Radigan M, Burton G, Cavaleri M, Jensen S. Impact of empowerment training on the professional work of family peer advocates. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010a doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.06.012. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olin SS, Hoagwood KE, Rodriguez J, Ramos B, Penn M, Crowe M, et al. The application of behavior change theory to family-based services: Improving parent empowerment in children’s mental health. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010b;19:462–470. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9317-3. doi:10.1007/s10826-009-9317-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens PL, Hoagwood K, Horwitz SM, Leaf PJ, Poduska JM, Kellam SG, et al. Barriers to children’s mental health services. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:731–738. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumariega AJ, Glover S, Holzer CE, Nguyen H. Utilization of mental health services in a tri-ethnic sample of adolescents. Community Mental Health Journal. 1998;34:145–156. doi: 10.1023/a:1018788901831. doi:10.1023/A:1018788901831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos A, Berger S, Harrison M. Family support report: A call to action. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Division of Mental Hygiene, Bureau of Child and Adolescent Services; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Salzer MS, Schwenk E, Brusilovskiy E. Certified peer specialist roles and activities: Results from a national survey. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:520–523. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.5.520. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.61.5.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan P, Hanish L, McKay M, Dickey M. Evaluating process in child and family interventions: Aggression prevention as an example. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:220–236. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.2.220. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.16.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckman B, Jensen M. Stages of small group development. Group and Organizational Studies. 1977;2:419–427. doi: 10.1177/105960117700200404. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health, Human Services . Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General—Executive summary. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health, Human Services . Translating behavioral science into action: Report of the National Advisory Mental Health Council’s Behavioral Science Workgroup. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health, Human Services . Mental health: Culture, race, ethnicity. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL. Cultural mistrust and mental health services for African Americans: A review and meta-analysis. The Counseling Psychologist. 2001;29:513–531. doi:10.1177/0011000001294003. [Google Scholar]