Abstract

Background

Stable trochanteric femur fractures can be treated successfully with conventional implants such as sliding hip screw, cephalomedullary nails, angular blade plates. However comminuted and unstable inter or subtrochanteric fractures with or without osteoporosis are challenging & prone to complications. The PF-LCP is a new implant that allows angular stability by creating fixed angle block for treatment of complex, comminuted proximal femoral fractures.

Method

We reviewed 30 patients with unstable inter or subtrochanteric fractures, which were stabilized with PF-LCP. Mean age of patient was 65 years, and average operative time was 80 min. Patients were followed up for a period of 3 years (June 2010–June 2013). Patients were examined regularly at 3 weekly interval for signs of union (radiological & clinical), varus collapse (neck-shaft angle), limb shortening, and hardware failure.

Result

All patients showed signs of union at an average of 9 weeks (8–10 weeks), with minimum varus collapse (<10°), & no limb shortening and hardware failure. Results were analysed using IOWA (Larson) hip scoring. Average IOWA hip score was 77.5.

Conclusion

PF-LCP represents a feasible alternative for treatment of unstable inter- or subtrochanteric fractures.

Keywords: Proximal femur, Unstable, Angular stability, PF-LCP, Osteoporosis

1. Introduction

Proximal femoral fractures are one of the commonest fractures encountered in orthopaedic trauma practice (about 3 lakh per year1 with mortality rate of 4.5%–22%2). Hence the interest in development of improvements in management of these fractures remains high.

Extracapsular proximal femoral fractures are those occurring in the region extending from extracapsular basilar neck region to 5 cm below lesser trochanter. Proximal femoral fractures include intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures.3 Stable proximal femoral fractures can be managed with conventional implant with predictable results whereas unstable fractures are challenging, and prone to complications. There is a lack of consensus on the treatment for unstable proximal femoral fractures. Here we report our experience of complex extracapsular proximal femoral fractures with proximal femoral locking plate. Although good results are obtained with use of locking plate for complex fractures in other anatomic regions but scanty literature exists regarding their long term use in proximal femoral regions. Our aim is to evaluate the mid term clinical and functional outcome of PF-LCP in management of complex proximal femoral fractures with regards to complications, mortality, re-operations and outcome.

2. Methods

Our study included a total 30 patients (20 males & 10 females) with unstable proximal femoral fractures (AO Type3 31A2 & 31A3) who were subjected to management using PF-LCP. The mean age of the patients was 65 years (36–82 years). Extracapsular proximal femoral fractures included both intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fracture. Intertrochanteric fractures were classified according to Evans, whereas subtrochanteric fractures were classified according to Seinsheimer. Open fracture, Pathological fracture, Inability to walk before fracture, Polytrauma patients, Bilateral trochanteric, with associated shaft fractures and patients with systemic manifestations were excluded from the study. Patients were followed up for a period of 3 years (June 2010–June 2013). Patients were examined regularly at 3 weekly interval for signs of union (radiological & clinical), varus collapse (neck-shaft angle), limb shortening, and hardware failure. Patients were allowed non-weight bearing ambulation from day after surgery. Toe-touch weight bearing was started at 3 weeks and full weight being at 8 weeks (subject to union criteria).

All the patients were evaluated for osteoporosis and were given specific scores (1–6) according to the SINGH'S INDEX.4

2.1. Surgical technique

PF-LCP implant is a limited contact, angular stable plate designed for management of complex proximal femoral fractures.5 PF-LCP is anatomically pre-contoured to fit the proximal femur (Figs. 1 and 2). There are separate implants for left and right side. Proximal portion is pre-contoured to fit at greater trochanter. There are distal combi-holes of variable length. Proximal hood has 5 holes which take purchase in head and neck of femur (5 mm). Most proximal screw is inserted at an angle of 95°. The second and third screws are inserted at an angle of about 90° in anterior & posterior planes respectively. The fourth screw is inserted at an angle of 120° and the fifth at an angle of 135° which acts as medial buttress screw (preventing varus collapse). The remaining distal screw-holes (5–13 holes) in PF-LCP are fixed to the femoral diaphysis and are like the holes in the classical locking plates, which allow either conventional (4.5 mm) or locking head screw (5 mm) at the level of shaft. Distal tip of plate is tapered for percutaneous insertion (Figs. 5–16).

Fig. 1.

Showing PF-LCP applied over bone model.

Fig. 2.

Showing PF-LCP applied over bone model.

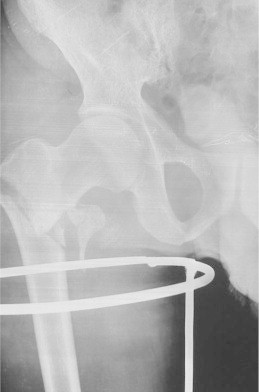

Fig. 5.

Showing unstable extracapsular proximal femoral fractures (Case no. 21).

Fig. 6.

Showing unstable extracapsular proximal femoral fractures (Case no. 21).

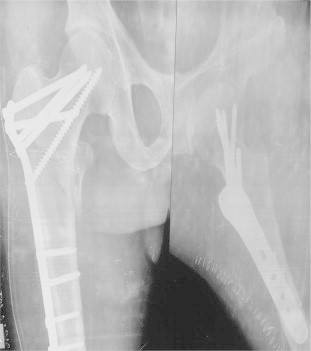

Fig. 7.

Showing immediate post op X-ray of the case (Case no. 21).

Fig. 8.

Showing immediate post op X-ray of the case (Case no. 21).

Fig. 9.

Showing 3 month post operative X-ray of the case (Case no. 21).

Fig. 10.

Showing 3 month post operative X-ray of the case (Case no. 21).

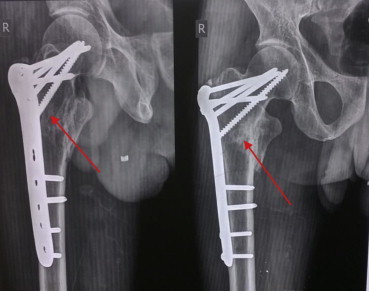

Fig. 11.

Showing unstable proximal femoral fracture (Case no. 3).

Fig. 12.

Showing immediate post op X-ray of the case (Case no. 3).

Fig. 13.

Showing immediate post op X-ray of the case (Case no. 3).

Fig. 14.

Showing united fracture – 3 month follow up (Case no. 3).

Fig. 15.

Showing unstable proximal femoral fractures (Case no. 14).

Fig. 16.

Showing fracture stabilized with PF-LCP (Case no. 14).

Surgery is performed with the patient lying supine over operating fracture table. Traction is applied and anatomically satisfactory reduction is achieved preoperatively under fluoroscopic control, in both anteroposterior and lateral views. Lateral approach using a straight incision extending from greater trochanter to 5–10 cm distally, according to fracture configuration, is used.

In cases where anatomically satisfactory reduction was achieved preoperatively the plate was inserted using the less invasive technique, while in others open reduction technique was used. Plate was temporarily fixed to shaft by k-wires, and both, alignment of plate and reduction was checked in anteroposterior & lateral views. Guide wires (3.2 mm) were inserted through guide sleeve in proximal hooded portion.

After checking the correct position of guide wire in AP & lateral views, guide wire is removed and drill is inserted through drill sleeve and screws of adequate length inserted making sure that satisfactory subchondral purchase is obtained. The position and length for all screws is rechecked on image intensifier, in both AP and lateral views. The plate is then fixed distally to the femoral shaft with a minimum three cortical screws of 4.5 mm (6 cortical purchases). In comminuted fractures 3–4 holes of plate were left empty at the level of fracture to increase working length. All comminuted fractures with calcar comminution were additionally bone grafted, primarily. Soft tissue was closed in layers with drain in situ.

Postoperatively patients were put on quadriceps drill and allowed non-weight bearing ambulation day after surgery. Toe-touch weight bearing was started at 3 weeks & full weight bearing at around 8 weeks, subject to union criteria (evidence of sufficient callus in 3 out of 4 cortices on AP and lateral views). Patients were followed up at 3 weekly interval for the first 3 months and looked for signs of union (Clinical & Radiological), varus collapse, limb shortening, and hardware failure (Figs. 5–17).

Fig. 17.

Showing union at fracture site with PF-LCP at 6 month follow up (Case no. 14).

3. Results

The median duration of surgery was 80 min (60–130 min). All 30 patients were available for evaluation after 3 years of follow up (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Perioperative and postoperative data (Average).

| Operating time (min) | 80 |

| Fluroscopy time (min) | 4–5 |

| Blood transfusion (units) | 0.5 |

| Mean follow up (months) | 36 |

| Mean fracture healing time (weeks) | 13.5 |

| Reoperation | 1 |

| Implant failure & non-union | NONE |

| Average IOWA HIP score | 77.5 |

Table 2.

Master chart.

| Case no. | Age (yrs) | Sex | Type of fracture | Blood loss | Operating time | Varus collapse | Limb shortening | Implant failure | Time for union |

IOWA HIP score | SINGH'S INDEX | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 wks | 6 wks | 12 wks | 6 mth | |||||||||||

| 1 | 40 | M | Evan-II | 100 ml | 90 min | 2 deg | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 82 | 6 |

| 2 | 48 | M | Seins-IIC | 120 ml | 120 min | 3 deg | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 80 | 5 |

| 3 | 60 | M | Seins-IIIA | 150 ml | 80 min | 5 deg | No | – | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | 72 | 5 |

| 4 | 70 | M | Seins-IIBA | 100 ml | 100 min | 3 deg. | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 79 | 3 |

| 5 | 38 | M | Evan-II | 150 ml | 60 min | 5 deg. | No | – | + | + | ++ | +++ | 72 | 6 |

| 6 | 80 | F | Seins-IV | 250 ml | 130 min | 10 deg | <1 cm | – | – | + | + | +++ | 74 | 3 |

| 7 | 56 | M | Seins-V | 250 ml | 120 min | 3 deg | No | – | + | + | ++ | +++ | 64 | 5 |

| 8 | 72 | M | Seins-IIIB | 200 ml | 100 min | 3 deg | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 76 | 5 |

| 9 | 59 | M | Evan-II | 100 ml | 60 min | – | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 89 | 4 |

| 10 | 71 | F | Seins-IIC | 180 ml | 120 min | 5 deg | No | – | + | + | +++ | +++ | 78 | 3 |

| 11 | 39 | M | Seins-IIIB | 220 ml | 90 min | – | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 84 | 6 |

| 12 | 41 | F | Seins-IIIB | 150 ml | 60 min | – | No | – | + | + | ++ | +++ | 86 | 6 |

| 13 | 43 | M | Evan-II | 180 ml | 90 min | 8 deg | <1 cm | – | – | + | + | +++ | 88 | 6 |

| 14 | 48 | M | Seins-IIIA | 200 ml | 60 min | – | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 83 | 6 |

| 15 | 50 | M | Evan-II | 220 ml | 100 min | 10 deg | <1 cms | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 81 | 5 |

| 16 | 75 | F | Seins-IV | 250 ml | 120 min | 9 deg | <1 cms | – | – | + | ++ | +++ | 75 | 3 |

| 17 | 65 | M | Seins-V | 150 ml | 60 min | – | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 65 | 4 |

| 18 | 38 | F | Evan-II | 100 ml | 100 min | – | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 89 | 6 |

| 19 | 35 | M | Seins-IIIB | 220 ml | 110 min | 7 deg | No | – | + | + | ++ | +++ | 72 | 6 |

| 20 | 55 | F | Seins-IIC | 250 ml | 120 min | 10 deg | <1 cms | – | – | + | + | +++ | 79 | 6 |

| 21 | 63 | M | Seins-IV | 140 ml | 130 min | – | No | – | + | + | ++ | ++ | 69 | 5 |

| 22 | 61 | F | Seins-IIB | 120 ml | 60 min | – | No | – | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | 74 | 6 |

| 23 | 62 | F | Evan-II | 180 ml | 70 min | 10 deg | <1 cms | – | – | + | + | +++ | 88 | 6 |

| 24 | 58 | M | Seins-IIIC | 200 ml | 100 min | 8 deg | No | – | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | 79 | 6 |

| 25 | 37 | M | Seins-IIC | 200 ml | 120 min | 8 deg | No | – | + | + | ++ | +++ | 76 | 6 |

| 26 | 48 | F | Seins-IIb | 180 ml | 130 min | 7 deg | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 80 | 6 |

| 27 | 46 | F | Seins-IV | 220 ml | 120 min | 12 deg | <1 cms | – | – | + | + | +++ | 74 | 6 |

| 28 | 55 | M | Seins-V | 200 ml | 100 min | 5 deg | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 62 | 6 |

| 29 | 59 | M | Seins-IV | 110 ml | 60 min | – | No | – | + | + | + | +++ | 68 | 6 |

| 30 | 64 | M | Evan-II | 100 ml | 70 min | – | No | – | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | 86 | 5 |

The union rate was 80% (24/30) at 3 months follow up. Average varus collapse was <10° (5–12°). No cases of limb shortening and hardware failure were noted. ROM at knee joint was full in all the cases (Table 2). However there was one case of greater trochanteric tip avulsion (case-6) in an 80 years old lady at 3 months follow. Patient had associated abductor lurch. She was advised fixation of trochanteric fragment, but refused. Although fracture healed in that case in usual time .This may be due to early full weight bearing by the patient. One patient showed delayed union at 6 month follow up, which was bone grafted. Follow up at 9 month showed full union in that case.

The mean blood-loss was 200 ml. The mean image intensifier time was 5 min and mean length of incision was 10 cm (Table 1).

Postoperatively assessment of the procedure was done using IOWA (Larson) Scoring system (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Till date, various classifications are available for the proximal femur fractures. Boyd and Griffin, in 1949, classified these fractures into Stable (two part), Unstable comminuted, Unstable reverse obliquity and Unstable intertrochanteric with subtrochanteric extension. The very commonly quoted, OTA/AO classification has three classes: 31A1-most stable, 31A2-more unstable and 31A3-most unstable.3

Initial treatment of the proximal femur fractures in the 1800s was mainly non-surgical. The major advances in the treatment of femoral fractures were first seen in 1870 when Hugh Owen Thomas6 developed the Thomas splint, and advocated immobilization with prolonged bed rest. Surgical management of the hip fractures started gaining interest when the first Bone plate was used in 1886 when Hanmann devised his retrievable bone plate. Lambotte, Lane (1914) Sherman (1912) and Townsend & Gilfillan (1943) played an important role in development of the modern principles of osteosynthesis.7 The real modern era of internal fixation of hip fractures began with the invention of the triflange nail by Smith-Peterson8 in1925. The invention of sliding compression with a cannulated system of drilling and insertion was invented by Godoy-Moreira and is the precursor of this class of implants in 1938. The desire to increase stability of unstable fracture patterns with valgus osteotomies was popularized by Dimon and Houston,9 Sarmiento, Harrington in the 1960s 1970s. Cephalomedullary implants are devices inserted with a closed technique and fluoroscopic control with variable femoral length geometry and enhanced proximal geometry to permit fixation with nails or screws into the femoral head. The Grosse-Kempf gamma nail and the Russel-Taylor reconstruction nail were the start of two new classes of intra-medullary devices designed for the hip region. Locked and hybrid compression plates have been applied recently for unstable fractures with only preliminary results so far.

Stable fractures of the proximal femur can be easily treated with osteosynthesis with conventional implants with predictable results. However management of unstable fractures is a challenge for the surgeon because of difficulty in obtaining anatomical reduction. Several plate designs have been developed over the last decades for the treatment of unstable fractures.10 Fracture stability is a relative term. It refers to the ability of the reduced fracture to support physiologic loading. Fracture stability refers not only to the number of fragments but the fracture planes as well. In my study, only unstable proximal femoral fractures11 (According to AO criteria) were included for study. It included fractures with:

-

a)

Large postero-medial fragment

-

b)

Reverse oblique pattern

-

c)

Shattered lateral wall, detached greater trochanter

-

d)

Inability to reduce fracture

Fixed nail plate devices used in the past for these fractures had high rates of cutout and fracture displacement. Subsequently, a sliding hip screw (DHS) was used with much success and became the predominant method of fixation for these fractures. Other implants used in the fixation of these fractures include Dynamic Condylar Screw (DCS), Angular blade plates, and the Cephalomedullary nails (PFN, PFNA, PFNAII, Gamma nail, Intertan).12 However complications such as head perforation, ‘cut-out’ of the femoral head screw, excessive sliding leading to shortening, primary or secondary varus collapse, plate pullout and plate breakage continued to be a problem with unstable fractures. The complication rate for unstable fractures treated with a DHS or a DCS plate has shown to be as high as 3–15%.13 Furthermore, dynamic hip screw or dynamic condylar screw plates,14 when used in unstable proximal femur fractures, cannot adequately prevent a secondary limb shortening after weight bearing due to lateralization of the head/neck fragment from gliding along the screw .Several authors propose use of anti-rotation screw or trochanteric stabilization plate in unstable fractures. The use of cephalomedullary nails when compared to dynamic hip screw exhibits increased stability while no difference was observed in operating time and intraoperative complication rate. Gamma nail in particular was associated with higher rate of complications like fractute at distal tip, penetration of screw into joint and backout of screw.15Watson and Moed16 reported that cephalomedullary nailing may block healing of the proximal fragment to the lateral wall by lying between the main fracture fragment and may cause delayed healing in A2 type fractures.

Intertrochanteric fractures occur in people with poor bone quality, about half of the intertrochanteric fractures are comminuted and unstable. In these fractures, excessive medialization of the shaft and subsequent loss of contact between the fragments can lead to fixation failure. Even after the fracture ultimately unites, limb shortening and decreased length of the abductor lever arm adversely affect hip function. Therefore unstable hip fractures should be differentiated from their stable counterparts with regard to treatment plan and prognosis.

The locking compression plate was introduced in the 21st century as a new implant that allows angular stable plating for the treatment of complex comminuted and osteoporotic fractures. The Locking Compression Plate (LCP) has the option of using the dynamic compression hole or the threaded locking hole or both. This combination provides the flexibility of cortex screw or locking screw fixation.17–21

More recently, locking plates especially designed for the proximal femur, PF-LCP have become available especially for the management of complex trochanteric fractures22 (Figs. 1 and 2).

Biomechanical studies have shown LCPs to achieve stronger and stiffer fixation than other angularly stable implants.17

PF-LCP acts as a fixed angle internal fixator device and achieves greater stability compared with DHS/DCS/Angle blade plate while avoiding excessive bone removal. It is also ideal in osteoporotic bones. PF-LCP prevents rotational instability and allows angular stability by creating a fixed angle block for treatment of complex, comminuted proximal femoral fractures. 5 proximal locking screws (5 mm, non cannulated) provide an angular stable construct independent of bone quality. The varied angle of multiple screw insertions within the complex trabecular zone of the head neck region of proximal femur, provides for an optimal mechanical stability. Further 120–135° screws provide calcar stability and maintain neck shaft angle (prevent varus collapse). The use of multiple screws in the head neck area effectively increases the overall cross sectional purchase in this anatomically peculiar area.

It has been reported that in unstable proximal femoral fracture with no lateral wall, no lag screw should be applied23 (No lateral wall – No lag screw) as this leads to medialisation of femoral shaft and lateralization of proximal femoral fragment. This results in deformity, non-union and screw cutout.

PF-LCP is ideal in such fractures. It acts as a buttress and prevents excessive fracture collapse. It substitutes for an incompetent lateral cortex. Our results shows minimal varus collapse and no hardware failure (Table 2).

Various authors have used reverse LISS femoral locking plate24,25 (Figs. 3 and 4) for unstable fractures of proximal femur but in our experience, this particular implant is not mechanically suited for anatomically sitting on proximal femur.

Fig. 3.

Showing reverse LISS applied over bone model; proximal portion is not sitting properly.

Fig. 4.

Showing reverse LISS applied over bone model; proximal portion is not sitting properly.

Our study has one limitations; it is a case series and not a comparison between two surgical technique in a randomized fashion. But it has two main strengths, first it is a unique study describing a new technique with new implant, second the data analysed here pertain to a specific type of injury; all the fractures were unstable proximal femoral fractures.

5. Conclusion

PF-LCP is an effective implant for unstable proximal femoral fractures (±osteoporosis). PF-LCP provides fixed angle block and provide angular stability with early functional rehabilitation.

Conflicts of interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Footnotes

Place of study – Lady Hardinge Medical College and RML Hospital.

References

- 1.Ehmke L.W., Fitzpatrick D.C., Krieg J.C. Lag screws for hip fracture fixation: evaluation of migration resistance under simulated walking. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:1329–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2005.05.002.1100230614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobbs R.E., Parvizi J., Lewallen D.G. Perioperative morbidity and 30-day mortality after intertrochanteric hip fractures treated by internal fixation or arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(8):963–966. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockwood and green’s fractures in adults, vol. 2, 7th ed. Intertrochanteric Fractures. Thomas A Russell. Page 1597–1600.

- 4.Koot V.C.M., Kesselaer S.M.M.J., Clevers G.J., DeHooge P., Weits T. Evaluation of the singh index for measuring osteoporosis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1996;78-B:831–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasenboehler Erik A., Agudelo Juan F., Morgan Steven J., Smith Wade R., Hak David J., Stahel Philip F. Treatment of complex proximal femoral fractures with proximal femur locking compression plate. Orthopaedics. August 2007;30(8) doi: 10.3928/01477447-20070801-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hugh Owen Thomas, quoted by Rockwood CA, Green DP. Fracture in Adults, 4th ed., vol. 2, 1972–73.

- 7.Townsend Kenneth, Gilfillan Charles. A new type of bone plate and screws. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1943;77:595–597. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith Peterson M. Treatment of neck of femur by internal fixation. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1937;64:287. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimon J.H.J.C. Unstable intertrochanteric fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49(3):440–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medoff R.M. A new device for the fixation of unstable pertrochanteric fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(8):1192–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knobe Mathias, Gradl Gertraud, burger Andreasladen, Tarkin Ivans S., Pape Hanschristoph. February 2013. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 11999-013-2834-9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma V., Babhulkar S., Babhulkar S. Role of gamma nail in management of pertrochanteric fractures of femur. Indian J Orthop. 2008;42:212–216. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.40260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson A.H., Varty K., Dodd C.A. Sliding hip screws: modes of failure. Injury. 1989;20:227–231. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(89)90120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nungu K.S., Olerud C., Rehnberg L. Treatment of subtrochanteric fractures with the AO dynamic condylar screw. Injury. 1993;24:90–92. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(93)90195-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butt, Krikler S.J., Nafie, Ali Comparison of dynamic hip screw and gamma nail; a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Injury. 1995 nov;26(9):615–618. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(95)00126-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson J.T., Moed B.R. Ipsilateral femoral neck and shaft fractures; complications and their treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;399:78. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200206000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koval K.J., Zuckerman J.D. Hip fractures: II. Evaluation and treatment of intertrochanteric fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1994;2:150–156. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wieser K., Babst R. Fixation failure of the LCP proximal femoral plate 4.5/5.0 in patients with missing posteromedial support in unstable per-, inter-, and subtrochanteric fractures of the proximal femur. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:1281–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haidukewych G.J., Israel T.A., Berry D.J. Reverse obliquity fractures of the intertrochanteric region of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:643–650. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadowski C., Lubbeke A., Saudan M. Treatment of reverse oblique and transverse intertrochanteric fractures with use of an intramedullary nail or a 95° screw-plate: a prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:372–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Archdeacon M., Ford K.R., Wyrick J. A prospective functional outcome and motion analysis evaluation of the hip abductors after femur fracture and antegrade nailing. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:3–9. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31816073b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forte M.L., Virnig B.A., Kane R.L. Geographic variation in device use for intertrochanteric hip fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:691–699. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haidukewych George J. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:712–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozkaya Ufuk, Bilgili Fuat, Kilic Ayhan, Parmaksizoglu Atilla Sancar, Kabukcuoglu Yavuz. Minimally invasive management of unstable proximal femoral extracapsular fractures using reverse LISS femoral locking plates. Hip Int. 2009;19(2):141–147. doi: 10.1177/112070000901900211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma C.H., Tu Y.K., Yu S.W., Yen C.Y., Yeh J.H., Wu C.H. Reverse LISS plate for proximal femoral fractures. Injury. 2010 Aug;41(8):827–833. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]