Abstract

Background

The dopamine (DA) hypothesis of schizophrenia proposes the mental illness is caused by excessive transmission of dopamine in selected brain regions. Multiple lines of evidence, including blockage of dopamine receptors by antipsychotic drugs that are used to treat schizophrenia, support the hypothesis. However, the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) blockade cannot explain some important aspects of the therapeutic effect of antipsychotic drugs. In this study, we hypothesized that antipsychotic drugs could affect the transcription of genes in the DA pathway by altering their epigenetic profile.

Methods

To test this hypothesis, we examined the effect of olanzapine, a commonly used atypical antipsychotic drug, on the DNA methylation status of genes from DA neurotransmission in the brain and liver of rats. Genomic DNA isolated from hippocampus, cerebellum, and liver of olanzapine treated (n = 2) and control (n = 2) rats were analyzed using rat specific methylation arrays.

Results

Our results show that olanzapine causes methylation changes in genes encoding for DA receptors (dopamine D1 receptor, dopamine D2 receptor and dopamine D5 receptor), a DA transporter (solute carrier family 18 member 2), a DA synthesis (differential display clone 8), and a DA metabolism (catechol-O-methyltransferase). We assessed a total of 40 genes in the DA pathway and found 19 to be differentially methylated between olanzapine treated and control rats. Most (17/19) genes showed an increase in methylation, in their promoter regions with in silico analysis strongly indicating a functional potential to suppress transcription in the brain.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that chronic olanzapine may reduce DA activity by altering gene methylation. It may also explain the delayed therapeutic effect of antipsychotics, which occurs despite rapid dopamine blockade. Furthermore, given the common nature of epigenetic variation, this lends insight into the differential therapeutic response of psychotic patients who display adequate blockage of dopamine receptors.

Keywords: Dopamine, Psychosis, Olanzapine, DNA methylation, Epigenetics

Background

The cause of schizophrenia remains unclear, though much evidence suggests that it may be produced by an excess transmission of dopamine (DA) in selected brain regions [1]. The DA hypothesis is supported by a number of observations. First, there is evidence that psychosis is associated with a hyper-dopaminergic state [2, 3]. Second, all antipsychotic drugs block dopamine receptors, particularly D2 receptors [4]. Third, patients with schizophrenia have elevated D2 receptors producing a behavioral hypersensitivity to dopamine [4, 5]. Furthermore, despite the difficulties of replicating genome wide association studies and candidate gene studies in schizophrenia, a number of genes in the dopamine pathway, including dopamine D1 receptor (DRD1), dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2), dopamine D5 receptor (DRD5), differential display clone 8 (DDC), catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) and solute carrier family 18 member 2 (SLC18A2), which is also a vesicular monoamine transporter, have been identified as associated with schizophrenia [6]. These genes have diverse functions, which include dopamine synthesis and release, receptor occupancy, sensitivity of the dopamine receptors, and hyper-response of the receptor-signalling cascade [1]. Because all antipsychotic drugs block the D2 receptor, it is widely believed that the D2 blockade is central to the therapeutic efficacy of antipsychotic drugs. However, several empirical observations seem to be at odds with this assumption. First, while D2 blockade occurs within several hours, it takes days and sometimes weeks for patients to respond to treatment with antipsychotics [7]. Second, many patients show limited or no therapeutic response despite marked blockade of the D2 receptor [8]. Finally, some patients fail to respond to standard doses of a specific antipsychotic drug, which occurs despite adequate D2 blockade, while interestingly the patient will respond to an equivalent (in terms of D2 blockade) of a second drug [9, 10]. These clinical observations are complemented by imaging studies, which show that antipsychotic D2 blockade can only contribute a small percentage of the variation in antipsychotic effectiveness [11]. Epigenetic mechanisms, particularly DNA methylation, which is responsive to environmental factors [12, 13], have the potential to alter the levels of brain molecules and may contribute to psychotic symptoms and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia [14]. Indeed, recent reports have identified methylation differences in some genes implicated in schizophrenia, as reviewed by Dempster et al. [15]. We propose that antipsychotic drugs affect the transcription of genes in the DA pathway by altering their epigenetic profile. We further hypothesize that this alteration contributes to the therapeutic effect of antipsychotic drugs. In order to test this hypothesis, we have designed this study to assess the effect of a therapeutic dose of an antipsychotic drug (olanzapine) on DNA methylation in two neural (hippocampus, cerebellum) and one non-neural (liver) control tissue in vivo.

Methods

The study used a rat model and genome-wide DNA methylation following Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP). Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats of 12 weeks of age (250 - 300 g) were purchased from Charles River, PQ, Canada. Upon arrival, rats were separated into individual cages and housed in controlled humidity and temperature on a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 a.m.). The Institutional Animal Care Committee of the University of Western Ontario had approved all animal-related procedures used in this study following the Canadian and National Institute of Health Guides on animal experimentation. Animals were weighed and divided into two treatment groups with comparable means of weight. Their stress-induced locomotor activity (following a 5 min tail pinch) was recorded for 30 min using an automated open-field activity chamber (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA). A computer that detects the disruption of photocell beams recorded the number of beam breaks per five minutes for half an hour as each animal moves, and the average beam breaks/5 min bins was reported. The rats then received injections of olanzapine (Zyprexa, Lilly, IN, USA; 2.5 mg/kg, i.m.; n = 8) or vehicle (phosphate buffered saline (PBS); n = 8) between 1:30 pm and 3:00 pm daily for 19 days. On day 20, eighteen hours after the last olanzapine/vehicle injection, rats were subjected to stress-induced locomotor activity to assess the therapeutic efficacy of chronic olanzapine. Twenty-four hours after they were decapitated without anaesthesia, micro-punches of brain areas or liver samples were collected and flash frozen.

Genomic DNA isolated from hippocampus, cerebellum and liver from olanzapine treated (n = 2) and control (n = 2) rats were analyzed using rat methylation arrays. The genomic DNA was isolated from olanzapine treated and saline control samples of hippocampus, cerebellum, and liver to analyze DNA methylation using rat methylation arrays. Genomic DNA was isolated from the interphase layer of TRIzol using sodium citrate, followed by ethanol precipitation and purification using the QIAamp® DNA Micro Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). DNA was then quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Wilmington, DE) and all samples had OD260/OD280 nm ratios of 1.8–2.0 and OD260/OD230 nm ratios of 2.0–2.4. The methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP), sample labeling, hybridization, and processing were performed at Arraystar Inc. (Rockville, Maryland, USA). Data analysis involved the comparison of differentially enriched regions between drug exposed (E) and control (C) rats, the log2-ratio values were averaged and then used to calculate the M’ value [M’ = Average (log2 MeDIPE/InputE) - Average(log2 MeDIPC/InputC)] for each probe. NimbleScan sliding-window peak-finding algorithm was run on this data to find the differential enrichment peaks (DEP). Using an R script program, a hierarchical clustering analysis was completed. The probe data matrix was obtained by using PeakScores from differentially methylated regions selected by DEP analysis. This analysis used a “PeakScore” ≥2 to define the DEPs, which is equivalent to the average p-value ≤0.01, for all probes within the peak. This analysis deals with a total of 40 candidate genes of the dopaminergic pathway. “Gene List Venn Diagram” was used to assess the distribution of genes affected across tissue types [16]. Transcription factor binding sites of DRD5 that showed increased methylation in hippocampus, cerebellum and liver were identified using CTCFBSDB 2.0 [17].

Results

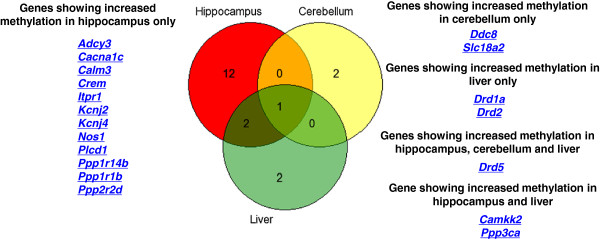

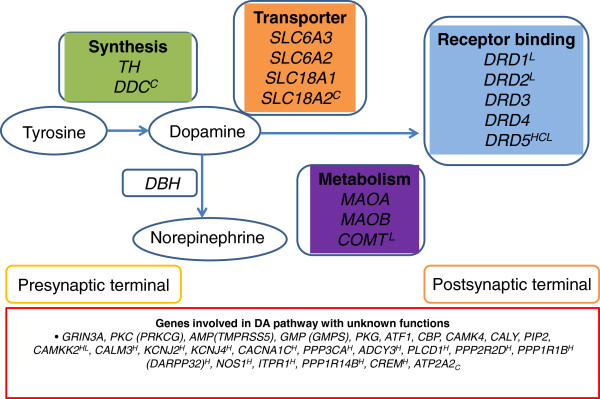

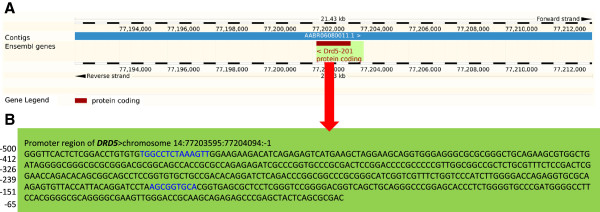

Stress-induced locomotor activity was significantly decreased (p = 0.001) in olanzapine treated rats 21 days post-stress (32.6 ± 4.4 beam breaks/5 min bins) as compared to that of matched-control (85.6 ± 7.3 beam breaks/5 min bins) (Table 1). Further, Table 2 shows 19 of the 40 genes that were differentially methylated (p < 0.01) as a result of olanzapine treatment in the three tissues (hippocampus, cerebellum and liver) studied. The major features of these results are four fold. First, the methylation changes are specific to the promoter regions of the genes. Second, most changes represent an increase in methylation as a result of olanzapine treatment. Third, the methylation changes are tissue (hippocampus, cerebellum, and liver) specific. Fourth and finally, most changes are specific to the hippocampus (Figure 1). For example, 15 of the 19 genes that showed significant increase in methylation are specific to hippocampus of olanzapine treated as compared to the matched control rats (Table 2). Also, 3 out of 40 genes showed significant increase (DRD5, SLC18A2 and DDC8) and one (ATP2A2) showed significant decrease in methylation in the cerebellum of olanzapine treated rats (Table 2). Furthermore, 5 of the 40 genes were differentially methylated in olanzapine treated liver as compared to the matched-controls (Table 2). These included the DA receptor genes (DRD1, DRD2 and DRD5), PPP3CA and CAMKK2. Also, one gene, COMT, showed decreased methylation in olanzapine treated liver samples. Overall, a number of genes related to DA functioning are differentially methylated as a consequence of olanzapine treatment in vivo. They are tissue (hippocampus) specific with only 2 of the 19 genes affected in hippocampus and liver (PPP3CA and CAMKK2); with one (DRD5) affected in all three tissues in the same direction (Figure 1). Furthermore, DARPP32, ADCY3 (AC3), DA receptor genes and a DA transporter gene (SLC18A2/VMAT2) were signified in the DA receptor signalling pathway amongst genes that showed significant increases in methylation following olanzapine treatment (Figure 2). Also, we assessed gene-specific sequences that were methylated in the olanzapine treated samples. The region of DRD5 that was differentially methylated following olanzapine treatment has the necessary features of a functioning promoter, as illustrated by the identified CTCF transcription factor binding sites (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Locomotor activity (average number of beam breaks/5 minutes ± stderr) of olanzapine treated rats and their matched-controls during day 0 and 21 as measured baseline (before stress) and post-stress (n = 8 per each group)

| Day 0 baseline | Day 0 post-stress | Day 21 baseline | Day 21 post-stress | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 22.0 ± 2.64 | 101.9 ± 4.00 | 17.1 ± 2.47 | 85.6 ± 7.28 |

| Olanzapine | 22.0 ± 2.65 | 94.7 ± 6.54 | 16.9 ± 2.67 | 32.6 ± 4.42 |

| p-values | 1 | 0.452 | 0.973 | 0.001 |

T-test was used to compute the significance of differences between olanzapine treated and control groups.

Table 2.

Candidate genes of the dopamine pathway, showing significantly increased methylation (p < 0.01 ) following olanzapine treatment in hippocampus, cerebellum and liver, in a rat model in vivo

| Gene name | Accession | Chr. | Strand | TSS | TTS | EH-CH | EC-CC | EL-CL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drd5 | NM_012768 | chr14 | - | 77769487 | 77768059 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Camkk2 | NM_031338 | chr12 | + | 34772493 | 34938479 | 1 | 1 | |

| Calm3 | NM_012518 | chr1 | - | 77252717 | 77245608 | 1 | ||

| Kcnj2 | NM_017296 | chr10 | + | 100574984 | 100576268 | 1 | ||

| Kcnj4 | NM_053870 | chr7 | - | 117603827 | 117601722 | 1 | ||

| Cacna1c | NM_012517 | chr4 | - | 155517389 | 154895690 | 1 | ||

| Ppp3ca | NM_017041 | chr2 | + | 234130175 | 234409232 | 1 | 1 | |

| Adcy3 | NM_130779 | chr6 | + | 27118324 | 27202275 | 1 | ||

| Plcd1 | NM_017035 | chr8 | - | 124052193 | 124023089 | 1 | ||

| Ppp2r2d | NM_144746 | chr1 | + | 198640770 | 198674758 | 1 | ||

| Ppp1r1b | NM_138521 | chr10 | + | 87121888 | 87131587 | 1 | ||

| Nos1 | NM_052799 | chr12 | - | 39869484 | 39811720 | 1 | ||

| Itpr1 | NM_001007235 | chr4 | + | 143705359 | 144030051 | 1 | ||

| Ppp1r14b | NM_172045 | chr1 | + | 209648656 | 209650767 | 1 | ||

| Crem | NM_001110860 | chr17 | + | 62770632 | 62837670 | 1 | ||

| Slc18a2 | NM_013031 | chr1 | + | 265789916 | 265824551 | 1 | ||

| Ddc8 | NM_001017481 | chr10 | - | 108349394 | 108336343 | 1 | ||

| Drd2 | NM_012547 | chr8 | + | 52641159 | 52707749 | 1 | ||

| Drd1a | NM_012546 | chr17 | + | 16655925 | 16658161 | 1 |

Chr chromosome, TSS transcription start site, TTS transcription termination site, EH-CH, EC-CC, EL-CL the number of differentially enriched peaks that showed increased in methylation in Olanzapine treated experimental (E) rats as compared to matched-controls (C) in hippocampus (H), cerebellum (C) and liver (L), respectively.

Figure 1.

Genes showing increased methylation in hippocampus, cerebellum and liver, following Olanzapine treatment. DRD5 was the only candidate gene that was found to be affected by Olanzapine treatment in both brain regions and the liver.

Figure 2.

Candidate genes in the dopaminergic pathway (adapted and modified from Yeh et al. Brain and Cognition 2012; 80: 282–289). Superscripts (H, C and L) represent the genes that showed increased methylation in hippocampus, cerebellum, or liver, respectively. Genes without a superscript were not affected by olanzapine treatment. Subscript (C) represents the gene that showed reduced methylation in the cerebellum.

Figure 3.

The genomic location and promoter region of the dopamine D5 receptor gene ( DRD5). (A) Chromosomal position of the DRD5 (from http://www.ensembl.org/index.html), which showed significantly increased methylation (p < 0.01) following olanzapine treatment. (B) Sequence of the promoter region of DRD5, with CTCF transcription factor binding sites highlighted in blue (identified using CTCFBSDB version 2.0 by Bao et al. Nucleic Acids Research 2008; 36, D83-D87). The frequency of A/C/G/T in the promoter sequence was 0.174/0.308/0.370/0.148, respectively. The CpG count in the promoter region was 50 out of 250 bp.

Discussion

The significant increase in weight gain of olanzapine treated animals in the present study and in previously reported studies [18] has suggested that the paradigm adapted was capable of causing the metabolic disturbances observed in patients taking chronic olanzapine [19]. Furthermore, the significantly reduced locomotor activity of olanzapine treated rats indicated the therapeutic efficacy of the drug administered, which was comparable to the dosage applied in previous studies [20]. This argument was further supported by the observed changes in methylation of DA pathway genes.

Of special interest to this report are the genes involved in dopamine synthesis, transport, receptor, metabolism, interaction, and function [6]. The rationale for this focus stemmed from the fact that although antipsychotics interact with some dopamine receptors (D2), the actual mechanism of clinical effect behind antipsychotic efficacy in the treatment of psychosis is not fully understood. What is missing from the dopamine hypothesis of psychosis is the understanding of the underlying molecular mechanism(s) that may begin to reveal the full spectrum of the antipsychotics effects. Specifically, the results of the present study suggest an involvement of DNA methylation in genes of the dopamine pathway as an essential epigenetic mechanism in treating psychosis [21]. Our results showed that olanzapine causes an increase in DNA methylation in a significant (~40%) number of genes with an important role in dopamine neurotransmission. These include genes involved in the dopamine synthesis, transport, receptor, and metabolism (Figure 2). Further, the majority of DA pathway genes affected by olanzapine treatment were found to be hippocampus-specific, which is viewed as one of the primary sites for schizophrenia symptoms [21–23]. Also, a number of genes identified in the current study have been previously implicated in schizophrenia [24–27]. This increase in methylation in the DA pathway candidate genes is expected to interfere with transcription and suppress the functional gene product [28]. We also assessed if the methylated regions of individual genes have the potential to interfere with transcription. The results argue that gene-specific differentially methylated regions (DMRs) have necessary features of active promoters. All the affected DA pathway genes were differentially methylated in their promoter regions and therefore could result in altered gene expression [29]. For example, the promoter region of the DRD5 gene is differentially methylated in all three tissues. This gene has been implicated in cognitive functions that include working memory [30]. Furthermore, DRD1 and DRD5 have been reported to have distinct regulatory roles on synaptic plasticity, spontaneous motor activity, memory and the information being processed by the hippocampus [31, 32]. Here we show that DRD5, which encodes the D5 subtype DA receptor, and has been previously described as a susceptibility gene for schizophrenia [33, 34], may result in diminished D5 subtype by increase in methylation following olanzapine treatment. This is expected in all three tissues studied. It is also known that DRD5 interacts with DRD2 in the process of augmenting or suppressing cellular functions [35]. Further, the DRD5 gene region differentially methylated in response to olanzapine is compatible with methylation specific interference of transcription, as we have identified in silico predicted CTCF transcription factor binding sites (Figure 3) that warrant further confirmation. Similarly, the expression of DRD2 could be regulated through methylation or demethylation of cytosines at the “putative” promoter region of DRD2[36–38]. Thus, the results included in this report offer a unifying mechanism of DNA methylation, which may represent the molecular basis for response to olanzapine, in a manner where the drug affects transcription of candidate genes from the dopamine pathway in addition to its effect on D2 blockade. This suggests that alterations to DNA methylation, in particular, and epigenetic changes, in general, may be used to develop novel strategies for the treatment of psychosis. We acknowledge the added value of confirming the methylation changes in the promoter regions of DA genes using an additional technique possibly involving a larger number of rats in our future study. Further, we intend to explore the expression of mRNA and proteins of relevant genes that are affected by DNA methylation so as to investigate the efficacy of olanzapine in treating psychosis via altering methylation status. Various confounding factors such as gene-diet/drug interactions could affect methylation changes [12, 39, 40]. Therefore, in the present study, proper caution was taken to exclude confounding factors that could possibly lead to methylation changes. For example, all experimental animals were kept in a uniform environment and were not exposed to other drugs or environments including diets, which may contribute to differences in methylation status of the treatment and control groups. All rats were of the same breed, sex, age and comparable body weight. They showed similar significant effects from olanzapine on weight gain and locomotor activity.

Conclusions

The results of the present study suggest that chronic olanzapine may reduce DA activity in the long-term by altering gene methylation. Furthermore, olanzapine induced gene methylation may explain the delayed therapeutic effect of the drug, which occurs despite the rapid dopamine blockade and differential therapeutic responses of psychotic patients showing adequate D2 blockade.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research and Dr. Shiva M. Singh held a Senior Research Fellowship from the Ontario Mental Health Foundation during the course of this study.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MGM: participated in designing this study, analyzed and interpreted the data, wrote the first draft and revised the manuscript. CAC and BIL revised the manuscript for critical intellectual contents. RNR and RO: participated from the very conception and design of study to revising the manuscript for critical intellectual contents. SMS: conceived and designed the study, interpreted the data, critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual contents. All authors have read and approved the manuscript as submitted.

Contributor Information

Melkaye G Melka, Email: mmelka@uwo.ca.

Christina A Castellani, Email: ccastel3@uwo.ca.

Benjamin I Laufer, Email: blaufer@uwo.ca.

Raj N Rajakumar, Email: nrajakum@uwo.ca.

Richard O’Reilly, Email: roreilly@uwo.ca.

Shiva M Singh, Email: ssingh@uwo.ca.

References

- 1.Madras BK. History of the discovery of the antipsychotic dopamine D2 receptor: a basis for the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. J Hist Neurosci. 2013;22:62–78. doi: 10.1080/0964704X.2012.678199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seeman P, Dopamine receptor sequences Therapeutic levels of neuroleptics occupy D2 receptors, clozapine occupies D4. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1992;7:261–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seeman P. Atypical antipsychotics: mechanism of action. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seeman P. Dopamine D2 receptors as treatment targets in schizophrenia. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2010;4:56–73. doi: 10.3371/CSRP.4.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corripio I, Escarti MJ, Portella MJ, Perez V, Grasa E, Sauras RB, Alonso A, Safont G, Camacho MV, Duenas R, Arranz B, San L, Catafau AM, Carrio I, Alvarez E. Density of striatal D2 receptors in untreated first-episode psychosis: an I123-IBZM SPECT study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:861–866. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeh TK, Hu CY, Yeh TC, Lin PJ, Wu CH, Lee PL, Chang CY. Association of polymorphisms in BDNF, MTHFR, and genes involved in the dopaminergic pathway with memory in a healthy Chinese population. Brain Cogn. 2012;80:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manschreck TC, Boshes RA. The CATIE schizophrenia trial: results, impact, controversy. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2007;15:245–258. doi: 10.1080/10673220701679838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapur S, Barsoum SC, Seeman P. Dopamine D(2) receptor blockade by haloperidol. (3)H-raclopride reveals much higher occupancy than EEDQ. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:595–598. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karagianis JL, LeDrew KK, Walker DJ. Switching treatment-resistant patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder to olanzapine: a one-year open-label study with five-year follow-up. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19:473–480. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mancama D, Arranz MJ, Kerwin RW. Pharmacogenomics of psychiatric drug treatment. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2003;5:642–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yilmaz Z, Zai CC, Hwang R, Mann S, Arenovich T, Remington G, Daskalakis ZJ. Antipsychotics, dopamine D(2) receptor occupancy and clinical improvement in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2012;140:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh SM, Murphy B, O’Reilly RL. Involvement of gene-diet/drug interaction in DNA methylation and its contribution to complex diseases: from cancer to schizophrenia. Clin Genet. 2003;64:451–460. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-0004.2003.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petronis A. The origin of schizophrenia: genetic thesis, epigenetic antithesis, and resolving synthesis. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:965–970. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roth TL, Lubin FD, Sodhi M, Kleinman JE. Epigenetic mechanisms in schizophrenia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:869–877. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dempster E, Viana J, Pidsley R, Mill J. Epigenetic studies of schizophrenia: progress, predicaments, and promises for the future. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:11–16. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pirooznia M, Nagarajan V, Deng Y. GeneVenn - a web application for comparing gene lists using Venn diagrams. Bioinformation. 2007;1:420–422. doi: 10.6026/97320630001420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bao L, Zhou M, Cui Y. CTCFBSDB: a CTCF binding site database for characterization of vertebrate genomic insulators. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D83–D87. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng C, Lian J, Pai N, Huang XF. Reducing olanzapine-induced weight gain side effect by using betahistine: a study in the rat model. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:1271–1279. doi: 10.1177/0269881112449396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiner A, Niehaus D, Shuriquie NA, Aadamsoo K, Korcsog P, Salinas R, Theodoropoulou P, Fernandez LG, Ucok A, Tessier C, Bergmans P, Hoeben D. Metabolic effects of paliperidone extended release versus oral olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:449–457. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31825cccad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bardgett ME, Humphrey WM, Csernansky JG. The effects of excitotoxic hippocampal lesions in rats on risperidone- and olanzapine-induced locomotor suppression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:930–938. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grace AA. Dopamine system dysregulation by the hippocampus: implications for the pathophysiology and treatment of schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology. 2011;62:1342–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jun H, Mohammed Qasim Hussaini S, Rigby MJ, Jang MH. Functional role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis as a therapeutic strategy for mental disorders. Neural Plast. 2012;2012:1–20. doi: 10.1155/2012/854285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisenberg DP, Ianni AM, Wei SM, Kohn PD, Kolachana B, Apud J, Weinberger DR, Berman KF. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val(66)Met polymorphism differentially predicts hippocampal function in medication-free patients with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(6):713–720. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donohoe G, Walters J, Morris DW, Quinn EM, Judge R, Norton N, Giegling I, Hartmann AM, Moller HJ, Muglia P, Williams H, Moskvina V, Peel R, O’Donoghue T, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, Gill M, Rujescu D, Corvin A. Influence of NOS1 on verbal intelligence and working memory in both patients with schizophrenia and healthy control subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1045–1054. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green EK, Grozeva D, Jones I, Jones L, Kirov G, Caesar S, Gordon-Smith K, Fraser C, Forty L, Russell E, Hamshere ML, Moskvina V, Nikolov I, Farmer A, McGuffin P, Holmans PA, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, Craddock N, Consortium Wellcome Trust Case Control The bipolar disorder risk allele at CACNA1C also confers risk of recurrent major depression and of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:1016–1022. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer-Lindenberg A, Straub RE, Lipska BK, Verchinski BA, Goldberg T, Callicott JH, Egan MF, Huffaker SS, Mattay VS, Kolachana B, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR. Genetic evidence implicating DARPP-32 in human frontostriatal structure, function, and cognition. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:672–682. doi: 10.1172/JCI30413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pal P, Mihanovic M, Molnar S, Xi H, Sun G, Guha S, Jeran N, Tomljenovic A, Malnar A, Missoni S, Deka R, Rudan P. Association of tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms on 8 candidate genes in dopaminergic pathway with schizophrenia in Croatian population. Croat Med J. 2009;50:361–369. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2009.50.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Razin A, Cedar H. DNA methylation and gene expression. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:451–458. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.451-458.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng W, Dong Z, He B, Wang K. Analysis method of epigenetic DNA methylation to dynamically investigate the functional activity of transcription factors in gene expression. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:532–2164. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loo SK, Rich EC, Ishii J, McGough J, McCracken J, Nelson S, Smalley SL. Cognitive functioning in affected sibling pairs with ADHD: familial clustering and dopamine genes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:950–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centonze D, Grande C, Saulle E, Martin AB, Gubellini P, Pavon N, Pisani A, Bernardi G, Moratalla R, Calabresi P. Distinct roles of D1 and D5 dopamine receptors in motor activity and striatal synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8506–8512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08506.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansen N, Manahan-Vaughan D. Cereb Cortex. 2012. Dopamine D1/D5 Receptors Mediate Informational Saliency that Promotes Persistent Hippocampal Long-Term Plasticity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:635–645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Den Bossche MJ, Strazisar M, Cammaerts S, Liekens AM, Vandeweyer G, Depreeuw V, Mattheijssens M, Lenaerts AS, De Zutter S, De Rijk P, Sabbe B, Del-Favero J. Identification of rare copy number variants in high burden schizophrenia families. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2013;162:273–282. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee D, Huang W, Lim AT. Dopamine induces a biphasic modulation of hypothalamic ANF neurons: a ligand concentration-dependent effect involving D5 and D2 receptor interaction. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5:39–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popendikyte V, Laurinavicius A, Paterson AD, Macciardi F, Kennedy JL, Petronis A. DNA methylation at the putative promoter region of the human dopamine D2 receptor gene. Neuroreport. 1999;10:1249–1255. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199904260-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roig B, Virgos C, Franco N, Martorell L, Valero J, Costas J, Carracedo A, Labad A, Vilella E. The discoidin domain receptor 1 as a novel susceptibility gene for schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:833–841. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertolino A, Fazio L, Caforio G, Blasi G, Rampino A, Romano R, Di Giorgio A, Taurisano P, Papp A, Pinsonneault J, Wang D, Nardini M, Popolizio T, Sadee W. Functional variants of the dopamine receptor D2 gene modulate prefronto-striatal phenotypes in schizophrenia. Brain. 2009;132:417–425. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anier K, Malinovskaja K, Pruus K, Aonurm-Helm A, Zharkovsky A, Kalda A. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013. Maternal separation is associated with DNA methylation and behavioural changes in adult rats. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh S, Li SS. Epigenetic effects of environmental chemicals bisphenol a and phthalates. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:10143–10153. doi: 10.3390/ijms130810143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]