Abstract

Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is heritable and neurodevelopmental with unknown causes. The serotonergic and oxytocinergic systems are of interest in autism for several reasons: (i) Both systems are implicated in social behavior, and abnormal levels of serotonin and oxytocin have been found in people with ASD; (ii) treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and oxytocin can yield improvements; and (iii) previous association studies have linked the serotonin transporter (SERT; SLC6A4), serotonin receptor 2A (HTR2A), and oxytocin receptor (OXTR) genes with ASD. We examined their association with high functioning autism (HFA) including siblings and their interaction.

Methods

In this association study with HFA children (IQ > 80), siblings, and controls, participants were genotyped for four single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in OXTR (rs2301261, rs53576, rs2254298, rs2268494) and one in HTR2A (rs6311) as well as the triallelic HTTLPR (SERT polymorphism).

Results

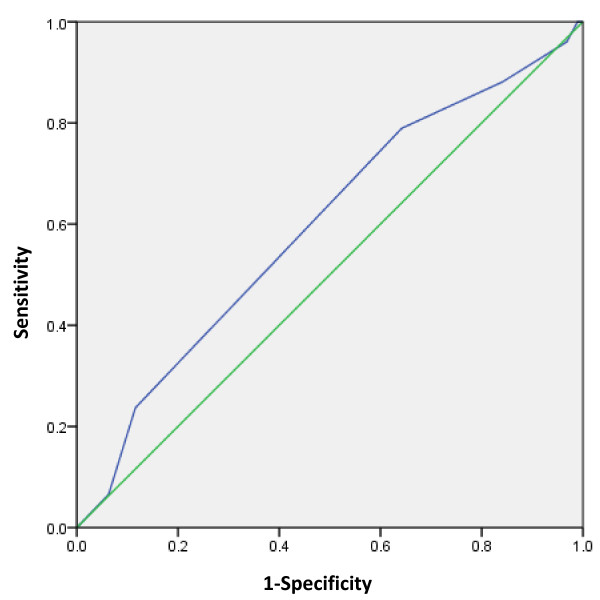

We identified a nominal significant association with HFA for the HTTLPR s allele (consisting of S and LG alleles) (p = .040; odds ratio (OR) = 1.697, 95% CI 1.191–2.204)). Four polymorphisms (HTTLPR, HTR2A rs6311, OXTR rs2254298 and rs53576) in combination conferred nominal significant risk for HFA with a genetic score of ≥4 (OR = 2.09, 95% CI 1.05–4.18, p = .037). The resulting area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.595 (p = .033).

Conclusions

Our findings, combined with those of previous reports, indicate that ASD, in particular HFA, is polygenetic rather than monogenetic and involves the serotonergic and oxytocin pathways, probably in combination with other factors.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/2049-9256-2-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, High functioning autism, Oxytocin receptor, Polymorphism, Serotonin receptor 2A, Serotonin transporter

Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairments in social interactions and communication and by repetitive behaviors [1, 2]. An ASD diagnosis can be made very early in childhood, but the disorder is a lifelong condition. The prevalence is estimated to be 0.6–1.0% [3–6], with a male:female ratio of 4:1 [6]. Twin studies give an estimated heritability of 70–90% [7–10], implicating genetics as a main factor in the etiology, in addition to environmental factors. Some ASD cases are caused by single gene defects [11–13], but for most cases, the genetic causes are unknown.

Both the serotonergic and oxytocinergic systems seem to play a role in ASD and social behaviors [14]. The serotonergic system is of special interest in autism for several reasons: (i) In up to 30% of people with ASD, elevated whole blood serotonin (5-HT) levels have been reported [15]; (ii) ASD-related sensory motor behaviors are increased after depletion of tryptophan, a precursor in 5-HT synthesis [16]; (iii) reduced serotonin receptor 2A (HTR2A) and serotonin transporter (SERT, also known as 5-HTT) binding in certain brain regions of people with ASD has been identified [17–19]; (iv) selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can improve abnormal reciprocal social interaction and repetitive behaviors in some cases [20–23]; and (v) several polymorphisms in the HTR2A gene (NCBI Gene ID: 3356) and the SERT gene (also known as SLC6A4; NCBI Gene ID: 6532) have suggested association with ASD [24–29]. In the following, we focus on these two candidate genes: The promoter sequence of SERT contains a polymorphic region (HTTLPR) with a short allele (S) and a long allele (L) that is 44 bp longer and can contain an additional single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (rs25531), making the locus triallelic (LA, LG and S) [30, 31]. These polymorphisms affect SERT expression, with the S and LG alleles (here denoted collectively as the s allele, while LA as the l allele) reducing transcriptional efficiency [30, 31]. Still, some inconsistent results appear with s allele or l allele associations with ASD depending on ethnicity or diagnostic inclusion as found in a meta-analysis [24]. Association studies of HTR2A have concentrated mostly on three non-coding SNPs (rs6311, rs6313, rs6314) [26–28, 32].

Similarly, the oxytocinergic system has attracted attention for similar reasons: (i) Low plasma oxytocin levels have been observed in autistic boys [33, 34]; (ii) elevated oxytocin precursor levels in ASD children have been reported [33]; and (iii) administration of oxytocin has improved retention of social information and decreased repetitive behaviors in ASD as well as in high functioning autism (HFA) [35–38]. Nonetheless, genetic studies have mainly failed to associate the oxytocin gene with autism; however, several studies have reported an association with the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR; NCBI Gene ID: 5021), although inconsistently [39–43]. In particular the OXTR polymorphism: rs2301261, rs53576, rs2254298 and rs2268494, were studied in ASD and social behavior [40, 42–44].

Recent reports have indicated some interactions among 5-HT, serotonergic components, and oxytocin [14, 45, 46]. In the first report by Hammock et al. [45], plasma oxytocin and 5-HT levels were negatively correlated with each other, and this relationship was most prominent in children under age 11 years. Thanseem and colleagues [46], on the other hand, found that transcription factor–like specificity protein 1 expression in brains of ASD participants increased in parallel with dysregulation of the transcription of HTR2A (down-regulation) and OXTR (up-regulation), which might further reveal downstream pathways mediating brain developmental disorders. Moreover, Dolen et al. [14] could demonstrate in mice models that the rewarding properties of social interactions require the coordinated activity of oxytocin and 5-HT in the nucleus accumbens, and this oxytocin-induced synaptic plasticity requires activation of nucleus accumbens serotonin receptor 1B.

Because previous association studies of SERT, HTR2A, and OXTR have led to controversial findings, but the mentioned genes seem to interact with one another, we attempted to replicate these associations analyzing ASD children (high functioning), their siblings, and controls with no clinical diagnoses. In contrast to other studies, we included only patients with HFA in our study, eliminating confounding parameters such as IQ. Sibships transmission analysis was included to enhance further the case–control findings. Additionally, we tested for interaction among the three genes, since these were reported to be involved in ASD and even further to interact with each other, on the assumption that neurodevelopmental disorders are polygenetic rather than monogenetic.

Methods

Participants

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Canton Zurich, Switzerland (E-36/2009). Parents of all participants gave their written consent after being informed about the aim of the study. All participants (76 with HFA, 78 siblings, and 99 controls) were Caucasians between 5 and 17 years of age collected in the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the University of Zurich. In all patients diagnosis was confirmed using the Autism Diagnosis Observation Schedule [47] and the Autism Diagnosis Interview [48]. Inclusion criteria for all children with high-functioning ASD (64 males and 12 females) was IQ of at least 80 from at least one of two IQ tests (see below) according to strict HFA definition [49, 50] and all met the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) [51] criteria for pervasive developmental disorder, including three with childhood autism, 27 with atypical autism, and 46 with Asperger syndrome. Persons with neurological disorders including epilepsy or known genetic diseases linked to autism were excluded.

The siblings of the ASD group (33 males and 45 females) did not have an ASD diagnosis or other severe psychiatric disorders according to screening questionnaires (see below). For the control group, only children without any clinical diagnosis were included in the study (77 males and 22 females).

Additionally, all participants were screened for psychopathology with the following parent reports: Child Behaviour Checklist [52]; Social Responsiveness Scale [53]; Social Communication Questionnaire [54]; Conners [55]; and the German ADHD rating scale, FBB-HKS [56]. Intelligence was measured with the Snijders-Oomen Non-Verbal Intelligence Test 5.5-17 [57] and the Culture Fair Test [58]. Age and IQ distribution for the different study groups is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of age, sex, and IQ for each study group

| Mean | SD | Range | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in y) | ASD | 11.24 | 3.10 | 5–17 | 76 |

| Siblings* | 10.53 | 3.25 | 6–17 | 78 | |

| Controls | 11.77 | 3.01 | 6–17 | 99 | |

| IQ, SON | ASD | 108.68 | 16.03 | 80–140 | 75 |

| Siblings | 109.75 | 12.36 | 82–135 | 77 | |

| Controls | 112.19 | 12.53 | 86–140 | 99 | |

| IQ, CFT | ASD | 105.16 | 13.88 | 70–145 | 68 |

| Siblings | 104.55 | 10.65 | 85–142 | 73 | |

| Controls | 106.71 | 10.96 | 85–133 | 97 | |

| Male | Female | Ratio (M/F) | Total | ||

| (% total) | (% total) | ||||

| Sex | ASD | 64 (84.2) | 12 (15.8) | 5.33 | 76 |

| Siblings*+ | 33 (42.3) | 45 (57.7) | 0.733 | 78 | |

| Controls | 77 (77.8) | 22 (22.2) | 3.50 | 99 |

Abbreviations: ASD autism spectrum disorder, SD standard deviation, SON Snijders-Oomen Non-Verbal Intelligence Test 5.5-17, CFT Culture Fair Test, M Male, F Female.

Statistical analysis was conducted using χ2 tests. *p < .05 versus controls; +p < .05 versus ASD.

Genotyping analysis

Saliva samples for DNA isolation were collected from all recruited individuals using the Oragene DNA kit (DNA Genotek; Kanata, Canada). DNA was isolated from saliva according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Oragene™ DNA Purification Protocol, DNA Genotek). For rs2301261, rs2254298, rs2268494, and rs6311 (Assay ID: C_15756091_30; C_15981334_10; C_15874471_10 and C_8695278_10, respectively), genotyping was performed using TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assays (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA, USA). PCR was carried out on a CFX384™ Real-Time System (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, USA) in a 5 μl (10 μl for rs6311) volume using TaqMan® 2× Universal PCR Master Mix No AmpErase® UNG (Applied Biosystems) and 10 ng (22.5 ng for rs6311) of DNA. Initial enzyme activation was carried out at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 92°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min.

For rs25531 and HTTLPR analysis, the restriction fragment length polymorphism method was used. Amplification was carried out on a CFX384™ Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) in a 10 μl (rs25531) or 25 μl (HTTLPR) volume using GoTaq® Green Master Mix 2× (Promega; Madison, WI, USA).

For rs25531, the same primers as described previously were used [59]. PCR conditions were an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 64°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 40 s with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR product was digested overnight at 37°C with 10 U BamHI (Fermentas; Burlington, Canada) in a 20 μl volume containing 2 μl of the corresponding enzyme buffer. Fragments were visualized on a 3% agarose gel. The fragment size of the undigested G allele is 340 bp whereas the A allele is restricted to bands of 110 and 230 bp.

For HTTLPR, the primer sequences were 5′-TGC CGC TCT GAA TGC CAG CAC-3′ and 5′-GGG ATT CTG GTG CCA CCT AGA CG-3′. PCR conditions were similar to those for rs53576, but only 30 cycles were carried out at 95°C for 45 s, 66.5°C for 45 s, and 72°C at 1 min. Fifteen microliters of PCR product were run on a 3% agarose gel to distinguish the L allele (463 bp) and S allele (419 bp). The remaining PCR product was digested similarly as described above but with 20 U MspI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Visualization on 3% agarose gel allowed distinction of the G allele (bands of 61, 66, 162, 174, and 292 bp) from the A allele (61, 66, 292, and 336 bp) of rs25531.

Statistical analysis

Each study group and the total sample were tested for deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for all polymorphisms, and no significant departures were found (see Additional file 1: Table S1). Differences in genotype, allele, and carrier frequencies among the groups (HFA, controls, siblings) as well as between two HFA subgroups (atypical autism and Asperger autism) and the control group were tested with the χ2 test. A sibship disequilibrium test was performed for each polymorphism according to Horvath and Laird [60].

Gene–gene interactions were studied by comparing each combination of two polymorphisms. For each combination, a three-dimensional contingency table with “polymorphism 1 × polymorphism 2 × study group” was built, and a three dimensional χ2 test was performed. All analyses were done with Matlab version 7.10.0 (MathWorks).

Additionally, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed for the various combinations of genetic scores sums, simulating their polygenetic effects on the risk for ASD [61]. Genetic scores attributed to the allelic variations are listed in Additional file 1: Table S2. The area under the curve and its significance were calculated using SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp.).

The nominal significance threshold was set to 5% and the adjusted significance according Bonferroni for multiple testing was set to 0.8%. Power analysis was performed using G*Power version 3.1.6 [62, 63].

Results

Association of single SNPs with autism diagnosis

To investigate whether oxytocinergic and serotonergic system genes are associated with HFA, 253 children were genotyped for polymorphisms in the OXTR, HTR2A, and SERT. Genotype and minor allele frequencies for all six polymorphisms are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Genotype distribution, genotype frequencies, and minor allele frequencies for autism spectrum disorder (ASD), siblings, and control groups

| Polymorphism | Genotype distribution (Genotype frequency) | MAF (Allele) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTTLPR triallelic 1 | ss | sl | ll | |

| ASD | 24 (0.316) | 38 (0.500) | 14 (0.184) | 0.434 (l) |

| Siblings | 16 (0.208) | 43 (0.558) | 18 (0.234) | 0.487 (s) |

| Controls | 22 (0.248) | 51 (0.526) | 24 (0.247) | 0.490 (s) |

| HTR2A rs6311 2 | GG | GA | AA | A |

| ASD | 21 (0.276) | 34 (0.447) | 21 (0.276) | 0.500 |

| Siblings | 23 (0.295) | 35 (0.449) | 20 (0.256) | 0.481 |

| Controls | 29 (0.299) | 47 (0.485) | 21 (0.216) | 0.459 |

| OXTR rs2301261 | CC | CT | TT | T |

| ASD | 65 (0.855) | 11 (0.145) | 0 | 0.072 |

| Siblings | 67 (0.859) | 11 (0.141) | 0 | 0.071 |

| Controls | 84 (0.848) | 15 (0.152) | 0 | 0.076 |

| OXTR rs53576 1 | AA | AG | GG | A |

| ASD | 7 (0.092) | 34 (0.447) | 35 (0.461) | 0.316 |

| Siblings | 7 (0.091) | 37 (0.481) | 33 (0.429) | 0.331 |

| Controls | 9 (0.093) | 33 (0.340) | 55 (0.567) | 0.263 |

| OXTR rs2254298 | AA | AG | GG | A |

| ASD | 0 | 12 (0.158) | 64 (0.842) | 0.079 |

| Siblings | 0 | 13 (0.167) | 65 (0.833) | 0.083 |

| Controls | 0 | 21 (0.212) | 78 (0.788) | 0.106 |

| OXTR rs2268494 | AA | AT | TT | A |

| ASD | 0 | 13 (0.171) | 63 (0.829) | 0.086 |

| Siblings | 1 (0.013) | 9 (0.115) | 68 (0.872) | 0.071 |

| Controls | 0 | 17 (0.172) | 82 (0.828) | 0.086 |

Abbreviations: ASD autism spectrum disorder, OXTR oxytocin receptor, HTR2A serotonin receptor 2A, HTTLPR serotonin-transporter–linked polymorphic region, MAF minor allele frequency. 1Genotyping failed repeatedly for one sibling and two controls. 2Genotyping failed repeatedly for two controls.

HTTLPR triallelic polymorphism allele frequencies were nominal significantly associated with Asperger diagnosis (p = .040; odds ratio (OR) = 1.697 (95% CI 1.191–2.204)) with the s allele as a risk allele (Table 3). The absolute genotype frequencies for the Asperger group were 17, 23, and 6 for ss, sl, and ll genotypes, respectively, for a relative s allele frequency of 0.619 for the Asperger group compared to 0.490 in the control group. Furthermore, merging l carriers led to a trend for association (p = .073; OR = 1.998 (95% CI 1.234–2.763)). No association of the HTR2A and OXTR with autism was observed.

Table 3.

Statistical association analysis between autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or its subgroups (atypical and Asperger) compared to controls or siblings with all six polymorphisms

| p values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphism | AA vs. controls | AS vs. controls | ASD vs. controls | ASD vs. siblings |

| Genotype frequencies | ||||

| HTTLPR triallelic | 0.926 | 0.110 | 0.350 | 0.301 |

| HTR2A rs6311 | 0.720 | 0.299 | 0.661 | 0.949 |

| OXTR rs2301261 | 0.595 | 0.731 | 0.901 | 0.948 |

| OXTR rs53576 | 0.524 | 0.280 | 0.334 | 0.914 |

| OXTR rs2254298 | 0.460 | 0.592 | 0.363 | 0.883 |

| OXTR rs2268494 | 0.870 | 0.974 | 0.991 | 0.388 |

| Allele frequencies | ||||

| HTTLPR triallelic | 0.708 | 0.040 | 0.160 | 0.168 |

| HTR2A rs6311 | 0.591 | 0.410 | 0.446 | 0.736 |

| OXTR rs2301261 | 0.609 | 0.743 | 0.905 | 0.950 |

| OXTR rs53576 | 0.307 | 0.464 | 0.280 | 0.774 |

| OXTR rs2254298 | 0.486 | 0.614 | 0.390 | 0.888 |

| OXTR rs2268494 | 0.877 | 0.975 | 0.991 | 0.623 |

| Carrier frequencies [Carrier] | ||||

| HTTLPR triallelic [s] | 0.787 | 0.108 | 0.319 | 0.451 |

| HTTLPR triallelic [l] | 0.725 | 0.073 | 0.189 | 0.129 |

| HTR2A rs6311 [C] | 0.949 | 0.158 | 0.362 | 0.780 |

| HTR2A rs6311 [T] | 0.433 | 0.948 | 0.744 | 0.799 |

| OXTR rs53576 [G] | 0.776 | 0.579 | 0.988 | 0.980 |

| OXTR rs53576 [A] | 0.258 | 0.216 | 0.164 | 0.691 |

In the subgroup analysis the three childhood autism were not included in either AA or AS subgroup. Abbreviations: AA atypical autism, AS Asperger syndrome, ASD autism spectrum disorder, OXTR oxytocin receptor, HTR2A serotonin receptor 2A, HTTLPR serotonin-transporter–linked polymorphic region, vs. versus, Bold nominal significant.

Forty “mixed” sibships were included (sibships with affected and unaffected siblings). No significant transmission disequilibrium was detected for any of the tested polymorphisms (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of the sibship disequilibrium test

| Polymorphism | Allele | b | c | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTTLPR triallelic | l | 8 | 12 | .503 |

| HTR2A rs6311 | A | 6 | 10 | .455 |

| OXTR rs2301261 | C | 5 | 1 | .219 |

| OXTR rs53576 | T | 6 | 8 | .791 |

| OXTR rs2254298 | G | 1 | 2 | 1.000 |

| OXTR rs2268494 | T | 2 | 4 | .688 |

Abbreviations: OXTR oxytocin receptor, HTR2A serotonin receptor 2A, HTTLPR serotonin-transporter–linked polymorphic region. b = mentioned allele more often transmitted to affected siblings. c = mentioned allele more often transmitted to unaffected siblings. p = two-tailed p value.

Analysis of gene–gene interactions and the polygenetic risk for ASD

Testing for gene–gene interactions by a χ2-test revealed nominal significant association of HTTLPR and HTR2A (rs6311) with ASD, as well as of the two OXTR SNPs rs53576 and rs2268494 (Additional file 1: Table S3). Three SNPs on the OXTR showed strong linkage disequilibrium; between rs2301261 and rs2254298 (p = 4.58E-11) and between rs2254298 and rs2268494 (p = .005); probably causing high transmission of these variant combinations.

Since there is evidence in the literature for the involvement of oxytocinergic and serotonergic systems and their interactions with one another, we investigated the polygenetic gene scores of these variants and the risk for HFA. The strongest result for a polygenetic risk was with the combination of the polymorphisms HTTLPR, HTR2A rs6311, and OXTR rs2254298 and rs53576 (for other combinations, see Additional file 1: Table S4). A nominally significant ROC curve (p = .033) was obtained for this combination (Figure 1). The optimal point is at ~80% sensitivity and ~35% specificity or ~35% sensitivity with ~80% specificity. A genetic score cutoff of 4 or more, indicating more risk variants, resulted in an OR = 2.090 (95% CI 1.045–4.179, p = .037).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for the candidate polymorphism markers, serotonin transporter promoter length polymorphism (HTTLPR), serotonin receptor 2A ( HTR2A ) rs6311, oxytocin receptor ( OXTR ) rs2254298, and OXTR rs53576. AUC = 0.595, p = .033, 95% CI: 0.509–0.681. Sensitivity of ~80% with specificity of ~35% or sensitivity of ~35% with specificity of ~80%.

Discussion

ASD is a highly heritable neurodevelopmental disorder with suggested involvement of the serotonergic and oxytocinergic systems, but up to now, no clear association of polymorphisms with ASD has been found with a high effect size. Here, we evaluated children with HFA, their siblings, and controls using genotyping results for four SNPs in OXTR, one in HTR2A, and the HTTLPR length polymorphism. Our analysis showed that the s allele of the HTTLPR polymorphism was nominal significantly associated with HFA; however, it should be denoted that due to sample size the p-value is rather borderline. We did not observe any significant association in the selected SNPs for the HTR2A and OXTR variants with HFA.

Regarding association with HTR2A, our findings are consistent with some previous studies [26, 28, 32] reporting no association with autism. Only one study involving patients “rather severely affected from autism” [27] reported a link, but no information regarding IQ values was given.

Association studies of HTTLPR with ASD have led to contradictory results. Several have identified the S allele with ASD [25, 29, 64, 65] while others associated the L allele with ASD [32, 66, 67] or found no association at all [68–71]. Our results rather support the first group. In our analysis of the HTTLPR, however, we used a triallelic mode in which the A and G alleles in the L allele were taken into account.

In accordance with previous reports [42, 72] and a recent meta-analysis finding [44] in which no association between the OXTR polymorphisms rs53576 and rs2301261 with ASD was found, we also could not confirm one with HFA. Lerer et al. [40] identified an association between OXTR rs2268494 and autism diagnosis, but only when IQ was entered as a covariate. In our study, although our ASD population was stratified to IQ equal or larger than eighty, we could not confirm such a link. Concerning OXTR rs2254298, we also could not confirm an association with HFA, in contrast to several previous studies [40, 42, 59, 73]. Nevertheless, our finding supports the recent meta-analysis in which no association could be proven accept for the biological functioning domain [44].

Although only one SNP singly was associated with HFA in this work, the gene–gene interaction study linked combinations of the tested polymorphisms with HFA. Similarly, such gene interaction study between HTTLPR and OXTR was reported in prediction of maternal sensitivity [74], pointing to their possible influence in social behavior. Furthermore, the ROC analysis showed that four of the tested SNPs together led to sensitivity of 80% but at the cost of low specificity (35%) or vice versa.

The limitations of our study include the relatively small minor allele frequency for three of the OXTR polymorphisms and the sample size. Power analysis revealed that the power was sufficient only for a medium or large effect size. The power for small effect sizes (i.e., of 0.1) was below 20% for polymorphisms with two genotypes and about 30% if all three genotypes were present.

The strength of our study is the narrow phenotype regarding the intellectual and language ability and cognitive function. Most previous investigations have analyzed samples consisting of the complete spectrum of autism whereas in our investigation all individuals were diagnosed with HFA. In the past, 50–70% of autistic children were classified as intellectually disabled, but those with Asperger have, by definition, an IQ in the normal range [75] and typical language development.

As far as we know, only one study has investigated an association of OXTR in HFA, finding a weak association [72]. Of the 22 studied SNPs, one was nominally associated with autism diagnosis (p = .0185), which would not hold for Bonferroni correction for multiple testing [72]. Further research involving people with HFA has yielded evidence for an association with the oxytocin gene itself [76]; the CD38 gene [77], whose gene product is related to oxytocin secretion [78–80]; and the syntaxin 1A gene [81], whose gene product affects SERT function [82]. These findings indicate that some components of the serotonergic and oxytocinergic systems, other than those already extensively studied, might be involved in HFA. Additionally, similarly to the report by Carayol et al. [61], who combined the low-risk genes PITX, ATP2B2, SLC25A12, and EN2, we could show that a combination of four polymorphisms (HTTLPR, HTR2A rs6311, and OXTR rs2254298 and rs53576) confers a nominal significant risk for HFA. This result points to the possibility that these genes play a role in ASD, probably in combination with additional risk genes that should be further explored.

Conclusions

In summary, many studies have found associations of OXTR, HTR2A, and SERT with ASD, but we could not confirm these with HFA except for a nominal association with the HTTLPR polymorphism. Our findings might be explained by the fact that HFA individuals have different symptoms from others with ASD and by the wide heterogeneity in the ASD population. Of interest, however, a combination of those polymorphisms resulted in nominal significant risk for HFA, pointing to the importance of a polygenetic rather than monogenetic context, in which each gene contributes to a very small fraction of the phenotype. Therefore, we suggest that future association studies should look into this aspect and examine various combinations of risk genes with HFA.

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article (and its additional files).

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: Table S1: Results of testing for deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Table S2. Allelic variation used in the calculation of genetic score under an additive model. Table S3. Gene–gene interactions and their associations with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Table S4. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis results for the different combinations of polygenetic risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). (DOC 152 KB)

Acknowledgements

The work was partially supported by the “Studienstiftung Deutschland” and the “Bundesprogramm Chancengleichheit” 2009–2011 of the University Zürich. We thank Miryame Hofmann for her technical assistance as well as all the families and individuals for their participation.

Grant sponsor partially by the “Studienstiftung Deutschland” and the “Bundesprogramm Chancengleichheit” 2009–2011 of the University Zürich; Grant number: none.

Abbreviations

- ASD

Autism spectrum disorder

- HFA

High functioning autism

- 5-HT

Serotonin

- HTR2A

Serotonin receptor 2A

- HTTLPR

Promoter sequence of SERT contains a polymorphic region

- ICD-10

International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th Revision

- OR

Odds ratio

- OXTR

Oxytocin receptor

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SERTSLC6A4

Serotonin transporter

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SSRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JN carried out the molecular genetic studies and performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. SW conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. EB conceived of the study, and participated in its design and recruitment of participants. RG participated in the recruitment of participants. EG participated in the design of the study and coordination and performed the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Johanna Nyffeler, Email: johanna.nyffeler@swissonline.ch.

Susanne Walitza, Email: susanne.walitza@kjpdzh.ch.

Elise Bobrowski, Email: elise@bobrowski.org.

Ronnie Gundelfinger, Email: ronnie.gundelfinger@kjpdzh.ch.

Edna Grünblatt, Email: edna.gruenblatt@kjpdzh.ch.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . DSM-IV. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington DC: APA; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association . DSM-V. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Washington DC: APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams JG, Higgins JP, Brayne CE. Systematic review of prevalence studies of autism spectrum disorders. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(1):8–15. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.062083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elsabbagh M, Divan G, Koh YJ, Kim YS, Kauchali S, Marcin C, Montiel-Nava C, Patel V, Paula CS, Wang C, et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res. 2012;5(3):160–179. doi: 10.1002/aur.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun X, Allison C, Matthews FE, Sharp SJ, Auyeung B, Baron-Cohen S, Brayne C. Prevalence of autism in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Autism. 2013;4(1):7. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirtz D, Thurman DJ, Gwinn-Hardy K, Mohamed M, Chaudhuri AR, Zalutsky R. How common are the “common” neurologic disorders? Neurology. 2007;68(5):326–337. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252807.38124.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I, Bolton P, Simonoff E, Yuzda E, Rutter M. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol Med. 1995;25(1):63–77. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700028099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freitag CM. Genetic risk in autism: new associations and clinical testing. Expert opinion on medical diagnostics. 2011;5(4):347–356. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2011.579101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A, Phillips J, Cohen B, Torigoe T, Miller J, Fedele A, Collins J, Smith K, et al. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(11):1095–1102. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson EB, Koenen KC, McCormick MC, Munir K, Hallett V, Happe F, Plomin R, Ronald A. A multivariate twin study of autistic traits in 12-year-olds: testing the fractionable autism triad hypothesis. Behavior Genet. 2012;42(2):245–255. doi: 10.1007/s10519-011-9500-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curatolo P, Porfirio MC, Manzi B, Seri S. Autism in tuberous sclerosis. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2004;8(6):327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaSalle JM, Yasui DH. Evolving role of MeCP2 in Rett syndrome and autism. Epigenomics. 2009;1(1):119–130. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freitag CM. The genetics of autistic disorders and its clinical relevance: a review of the literature. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(1):2–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolen G, Darvishzadeh A, Huang KW, Malenka RC. Social reward requires coordinated activity of nucleus accumbens oxytocin and serotonin. Nature. 2013;501(7466):179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hranilovic D, Bujas-Petkovic Z, Vragovic R, Vuk T, Hock K, Jernej B. Hyperserotonemia in adults with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(10):1934–1940. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDougle CJ, Naylor ST, Cohen DJ, Aghajanian GK, Heninger GR, Price LH. Effects of tryptophan depletion in drug-free adults with autistic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(11):993–1000. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110029004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makkonen I, Riikonen R, Kokki H, Airaksinen MM, Kuikka JT. Serotonin and dopamine transporter binding in children with autism determined by SPECT. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(8):593–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura K, Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Tsujii M, Yoshikawa E, Futatsubashi M, Tsuchiya KJ, Sugihara G, Iwata Y, Suzuki K, et al. Brain serotonin and dopamine transporter bindings in adults with high-functioning autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):59–68. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy DG, Daly E, Schmitz N, Toal F, Murphy K, Curran S, Erlandsson K, Eersels J, Kerwin R, Ell P, et al. Cortical serotonin 5-HT2A receptor binding and social communication in adults with Asperger’s syndrome: an in vivo SPECT study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):934–936. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon CT, State RC, Nelson JE, Hamburger SD, Rapoport JL. A double-blind comparison of clomipramine, desipramine, and placebo in the treatment of autistic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(6):441–447. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820180039004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolevzon A, Mathewson KA, Hollander E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in autism: a review of efficacy and tolerability. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(3):407–414. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDougle CJ, Naylor ST, Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR, Heninger GR, Price LH. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluvoxamine in adults with autistic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(11):1001–1008. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110037005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dove D, Warren Z, McPheeters ML, Taylor JL, Sathe NA, Veenstra-VanderWeele J. Medications for adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4):717–726. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang CH, Santangelo SL. Autism and serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of medical genetics Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics: the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2008;147B(6):903–913. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kistner-Griffin E, Brune CW, Davis LK, Sutcliffe JS, Cox NJ, Cook EH., Jr Parent-of-origin effects of the serotonin transporter gene associated with autism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156(2):139–144. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guhathakurta S, Singh AS, Sinha S, Chatterjee A, Ahmed S, Ghosh S, Usha R. Analysis of serotonin receptor 2A gene (HTR2A): association study with autism spectrum disorder in the Indian population and investigation of the gene expression in peripheral blood leukocytes. Neurochem Int. 2009;55(8):754–759. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hranilovic D, Blazevic S, Babic M, Smurinic M, Bujas-Petkovic Z, Jernej B. 5-HT2A receptor gene polymorphisms in Croatian subjects with autistic disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(3):556–558. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Kim SJ, Lord C, Courchesne R, Akshoomoff N, Leventhal BL, Courchesne E, Cook EH., Jr Transmission disequilibrium studies of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor gene (HTR2A) in autism. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114(3):277–283. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devlin B, Cook EH, Jr, Coon H, Dawson G, Grigorenko EL, McMahon W, Minshew N, Pauls D, Smith M, Spence MA, et al. Autism and the serotonin transporter: the long and short of it. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(12):1110–1116. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu XZ, Lipsky RH, Zhu G, Akhtar LA, Taubman J, Greenberg BD, Xu K, Arnold PD, Richter MA, Kennedy JL, et al. Serotonin transporter promoter gain-of-function genotypes are linked to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78(5):815–826. doi: 10.1086/503850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Muller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274(5292):1527–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho IH, Yoo HJ, Park M, Lee YS, Kim SA. Family-based association study of 5-HTTLPR and the 5-HT2A receptor gene polymorphisms with autism spectrum disorder in Korean trios. Brain Res. 2007;1139:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green L, Fein D, Modahl C, Feinstein C, Waterhouse L, Morris M. Oxytocin and autistic disorder: alterations in peptide forms. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(8):609–613. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Modahl C, Green L, Fein D, Morris M, Waterhouse L, Feinstein C, Levin H. Plasma oxytocin levels in autistic children. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43(4):270–277. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hollander E, Bartz J, Chaplin W, Phillips A, Sumner J, Soorya L, Anagnostou E, Wasserman S. Oxytocin increases retention of social cognition in autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(4):498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hollander E, Novotny S, Hanratty M, Yaffe R, DeCaria CM, Aronowitz BR, Mosovich S. Oxytocin infusion reduces repetitive behaviors in adults with autistic and Asperger’s disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(1):193–198. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andari E, Duhamel JR, Zalla T, Herbrecht E, Leboyer M, Sirigu A. Promoting social behavior with oxytocin in high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(9):4389–4394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910249107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guastella AJ, Einfeld SL, Gray KM, Rinehart NJ, Tonge BJ, Lambert TJ, Hickie IB. Intranasal oxytocin improves emotion recognition for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(7):692–694. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammock EA, Young LJ. Oxytocin, vasopressin and pair bonding: implications for autism. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1476):2187–2198. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lerer E, Levi S, Salomon S, Darvasi A, Yirmiya N, Ebstein RP. Association between the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) gene and autism: relationship to Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales and cognition. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(10):980–988. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell DB, Datta D, Jones ST, Batey Lee E, Sutcliffe JS, Hammock EA, Levitt P. Association of oxytocin receptor (OXTR) gene variants with multiple phenotype domains of autism spectrum disorder. J Neurodev Disord. 2011;3(2):101–112. doi: 10.1007/s11689-010-9071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacob S, Brune CW, Carter CS, Leventhal BL, Lord C, Cook EH., Jr Association of the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) in Caucasian children and adolescents with autism. Neurosci Lett. 2007;417(1):6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anney R, Klei L, Pinto D, Regan R, Conroy J, Magalhaes TR, Correia C, Abrahams BS, Sykes N, Pagnamenta AT, et al. A genome-wide scan for common alleles affecting risk for autism. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(20):4072–4082. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. Psychiatr Genet. 2013. A sociability gene? Meta-analysis of oxytocin receptor genotype effects in humans; p. PMID: 23921259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hammock E, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Yan Z, Kerr TM, Morris M, Anderson GM, Carter CS, Cook EH, Jacob S. Examining autism spectrum disorders by biomarkers: example from the oxytocin and serotonin systems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(7):712–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thanseem I, Anitha A, Nakamura K, Suda S, Iwata K, Matsuzaki H, Ohtsubo M, Ueki T, Katayama T, Iwata Y, et al. Elevated transcription factor specificity protein 1 in autistic brains alters the expression of autism candidate genes. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(5):410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rühl D, Bölte S, Feineis-Matthews S, Poustka F. Diagnostische Beobachtungsskala für Autistische Störungen; Deutsche Fassung der Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) Switzerland: Verlag Hans Huber; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bölte S, Rühl D, Schmötzer G, Poustka F. Diagnostisches Interview für Autismus - Revidiert (ADI-R); Deutsche Fassung des Autism Diagnostic Interview - Revised. Switzerland: Verlag Hans Huber; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noterdaeme M, Wriedt E, Hohne C. Asperger’s syndrome and high-functioning autism: language, motor and cognitive profiles. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(6):475–481. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carpenter LA, Soorya L, Halpern D. Asperger’s syndrome and high-functioning autism. Pediatr Ann. 2009;38(1):30–35. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20090101-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.World Health Organization . ICD-10: International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (10th Rev. ed.) 10. New York, NY, USA: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arbeitsgruppe Kinder- Jugendlichen- und Familiendiagnostik . In: Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL); Elternfragebogen über das Verhalten von Kindern und Jugendlichen. 2. Döpfner M, Plück J, Bölte S, Lenz K, Melchers P, Heim K, editors. Köln: Arbeitsgruppe Kinder-, Jugend- und Familiendiagnostik (KJFD; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bölte S, Poustka F. In: Skala zur Erfassung sozialer Reaktivität - Dimensionale Autismus-Diagnostik; Deutsche Fassung der Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) Constantino J, Gruber C, editors. Bern, Switzerland: Verlag Hans Huber; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bölte S, Poustka F. Fragebogen zur Sozialen Kommunikation - Autismus-Screening; Deutsche Fassung des Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) Verlag Hans Huber: Bern, Switzerland; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Conners C. Conners 3TM. 3. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Döpfner M, Lehmkuhl G. FBB-HKS [Rating-scale for Hyperkinetic Disorder from the Diagnostic System for Mental Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV (DISYPS-KJ)] 2. Hofgrefe: Göttingen, Germany; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tellegen P, Winkel M, Laros J. Snijders Oomen Non-verbal Intelligence Test Revised (SON-R) Hofgrefe-Verlag: Göttingen, Germany; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weiss R. CFT 20-R: Grundintelligenztest Skala 2-Revision. Göttingen, Germany: Hofgrefe-Verlag; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu S, Jia M, Ruan Y, Liu J, Guo Y, Shuang M, Gong X, Zhang Y, Yang X, Zhang D. Positive association of the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) with autism in the Chinese Han population. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(1):74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horvath S, Laird NM. A discordant-sibship test for disequilibrium and linkage: no need for parental data. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63(6):1886–1897. doi: 10.1086/302137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carayol J, Schellenberg GD, Tores F, Hager J, Ziegler A, Dawson G. Assessing the impact of a combined analysis of four common low-risk genetic variants on autism risk. Mol Autism. 2010;1(1):4. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arieff Z, Kaur M, Gameeldien H, van der Merwe L, Bajic VB. 5-HTTLPR polymorphism: analysis in South African autistic individuals. Hum Biol. 2010;82(3):291–300. doi: 10.3378/027.082.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Conroy J, Meally E, Kearney G, Fitzgerald M, Gill M, Gallagher L. Serotonin transporter gene and autism: a haplotype analysis in an Irish autistic population. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9(6):587–593. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coutinho AM, Oliveira G, Morgadinho T, Fesel C, Macedo TR, Bento C, Marques C, Ataide A, Miguel T, Borges L, et al. Variants of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) significantly contribute to hyperserotonemia in autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9(3):264–271. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yirmiya N, Pilowsky T, Nemanov L, Arbelle S, Feinsilver T, Fried I, Ebstein RP. Evidence for an association with the serotonin transporter promoter region polymorphism and autism. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105(4):381–386. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Betancur C, Corbex M, Spielewoy C, Philippe A, Laplanche JL, Launay JM, Gillberg C, Mouren-Simeoni MC, Hamon M, Giros B, et al. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms and hyperserotonemia in autistic disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7(1):67–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ma DQ, Rabionet R, Konidari I, Jaworski J, Cukier HN, Wright HH, Abramson RK, Gilbert JR, Cuccaro ML, Pericak-Vance MA, et al. Association and gene-gene interaction of SLC6A4 and ITGB3 in autism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(2):477–483. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Persico AM, Pascucci T, Puglisi-Allegra S, Militerni R, Bravaccio C, Schneider C, Melmed R, Trillo S, Montecchi F, Palermo M, et al. Serotonin transporter gene promoter variants do not explain the hyperserotoninemia in autistic children. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7(7):795–800. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ramoz N, Reichert JG, Corwin TE, Smith CJ, Silverman JM, Hollander E, Buxbaum JD. Lack of evidence for association of the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4 with autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;60(2):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wermter AK, Kamp-Becker I, Hesse P, Schulte-Korne G, Strauch K, Remschmidt H. Evidence for the involvement of genetic variation in the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) in the etiology of autistic disorders on high-functioning level. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(2):629–639. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu X, Kawamura Y, Shimada T, Otowa T, Koishi S, Sugiyama T, Nishida H, Hashimoto O, Nakagami R, Tochigi M, et al. Association of the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) gene polymorphisms with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the Japanese population. J Hum Genet. 2010;55(3):137–141. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. Oxytocin receptor (OXTR) and serotonin transporter (5-HTT) genes associated with observed parenting. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2008;3(2):128–134. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Howlin P. Outcome in high-functioning adults with autism with and without early language delays: implications for the differentiation between autism and Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33(1):3–13. doi: 10.1023/A:1022270118899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chakrabarti B, Dudbridge F, Kent L, Wheelwright S, Hill-Cawthorne G, Allison C, Banerjee-Basu S, Baron-Cohen S. Genes related to sex steroids, neural growth, and social-emotional behavior are associated with autistic traits, empathy, and Asperger syndrome. Autism Res. 2009;2(3):157–177. doi: 10.1002/aur.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Munesue T, Yokoyama S, Nakamura K, Anitha A, Yamada K, Hayashi K, Asaka T, Liu HX, Jin D, Koizumi K, et al. Two genetic variants of CD38 in subjects with autism spectrum disorder and controls. Neurosci Res. 2010;67(2):181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ebstein RP, Israel S, Lerer E, Uzefovsky F, Shalev I, Gritsenko I, Riebold M, Salomon S, Yirmiya N. Arginine vasopressin and oxytocin modulate human social behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1167:87–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Higashida H, Yokoyama S, Huang JJ, Liu L, Ma WJ, Akther S, Higashida C, Kikuchi M, Minabe Y, Munesue T. Social memory, amnesia, and autism: brain oxytocin secretion is regulated by NAD + metabolites and single nucleotide polymorphisms of CD38. Neurochem Int. 2012;61(6):828–838. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jin D, Liu HX, Hirai H, Torashima T, Nagai T, Lopatina O, Shnayder NA, Yamada K, Noda M, Seike T, et al. CD38 is critical for social behaviour by regulating oxytocin secretion. Nature. 2007;446(7131):41–45. doi: 10.1038/nature05526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nakamura K, Anitha A, Yamada K, Tsujii M, Iwayama Y, Hattori E, Toyota T, Suda S, Takei N, Iwata Y, et al. Genetic and expression analyses reveal elevated expression of syntaxin 1A ( STX1A) in high functioning autism. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11(8):1073–1084. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Quick MW. Role of syntaxin 1A on serotonin transporter expression in developing thalamocortical neurons. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2002;20(3–5):219–224. doi: 10.1016/S0736-5748(02)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1: Results of testing for deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Table S2. Allelic variation used in the calculation of genetic score under an additive model. Table S3. Gene–gene interactions and their associations with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Table S4. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis results for the different combinations of polygenetic risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). (DOC 152 KB)