Abstract

In wind pollination, the release of pollen from anthers into airflows determines the quantity and timing of pollen available for pollination. Despite the ecological and evolutionary importance of pollen release, wind–stamen interactions are poorly understood, as are the specific forces that deliver pollen grains into airflows. We present empirical evidence that atmospheric turbulence acts directly on stamens in the cosmopolitan, wind-pollinated weed, Plantago lanceolata, causing resonant vibrations that release episodic bursts of pollen grains. In laboratory experiments, we show that stamens have mechanical properties corresponding to theoretically predicted ranges for turbulence-driven resonant vibrations. The mechanical excitation of stamens at their characteristic resonance frequency caused them to resonate, shedding pollen vigorously. The characteristic natural frequency of the stamens increased over time with each shedding episode due to the reduction in anther mass, which increased the mechanical energy required to trigger subsequent episodes. Field observations of a natural population under turbulent wind conditions were consistent with these laboratory results and demonstrated that pollen is released from resonating stamens excited by small eddies whose turnover periods are similar to the characteristic resonance frequency measured in the laboratory. Turbulence-driven vibration of stamens at resonance may be a primary mechanism for pollen shedding in wind-pollinated angiosperms. The capacity to release pollen in wind can be viewed as a primary factor distinguishing animal- from wind-pollinated plants, and selection on traits such as the damping ratio and flexural rigidity may be of consequence in evolutionary transitions between pollination systems.

Keywords: wind pollination, stamens, pollination syndromes, aeroelasticity

1. Introduction

The floral morphology of wind-pollinated plants is constrained by the aerodynamic requirements for pollen release, dispersal and capture, given that anemophilous pollination is governed by the principles of fluid dynamics [1]. Whereas the syndrome of floral traits commonly associated with wind-pollinated angiosperms includes reduced petals and sepals, feathery stigmas, smooth pollen grains, small pollen diameter, lessened pollen clumping and long thin stamens [1,2], there are many exceptions to the classic pollination syndrome (e.g. [3]) and there have been few attempts to evaluate experimentally the biomechanical significance of any of these traits. Understanding the interaction of wind and flowers in pollen release is particularly important as release dynamics determine the quantity and timing of pollen delivered into the air column [4]. Moreover, the acquisition of traits permitting release by wind is a crucial first step in the evolution of wind pollination from animal-pollinated ancestors [5,6], and thus a mechanistic understanding of release is necessary to determine which floral traits are relevant to this transition [6].

Wind-pollinated flowers are challenged to overcome the adhesion of pollen to the anther wall during anthesis because the grains are embedded in the low-speed boundary-layer air surrounding the anther [7–9]. One solution to this shedding problem is the generation of internal forces causing pollen grains to catapult or explode from the anther into the air column [10–12]; but these mechanisms appear to be quite restricted taxonomically and do not likely represent the general case for wind-pollinated angiosperms. Alternatively, pollen may be removed passively from the anther by aerodynamic forces (e.g. lift and drag) acting directly on pollen grains within a dehisced anther [9,13,14]. A third possibility, to be explored here, is that agitation of stamens or their supporting scapes or catkins by turbulent winds leads to accelerations sufficient to expel grains into the air column [7, 9,15–17].

Theoretical analyses of wind–stamen interactions have indicated that the agitation of stamens by atmospheric turbulence (i.e. unsteady forces) may be more important for pollen release than steady boundary-layer forces on the anther walls (i.e. the second release mechanism described above) [8,9]. Stamens possessing natural frequencies, flexural rigidities and damping ratios characteristic of wind-pollinated species, were predicted to interact with small turbulent eddies whose fluctuating kinetic energy is transferred to the stamens, leading to resonant vibrations and thus pollen shedding. Not surprisingly then, the stamens of many wind-pollinated plants vibrate readily even under low wind speeds (e.g. wind-pollinated species of Aceraceae, Gunneraceae, Plantaginaceae, Poaceae and Ranunculaceae; D.T., personal observations, 2010) [7,8,16,17]. However, neither the mechanical properties of wind-pollinated stamens nor the dynamics of the resulting oscillations have been evaluated experimentally.

Here, we investigate the mechanical response of stamens of the cosmopolitan herbaceous weed Plantago lanceolata L. (Plantaginaeceae) to vibrations. Plantago lanceolata is a useful plant for studying vibration-induced pollen release because it is wind-pollinated, easily grown and flowers quickly [18]. First, we apply a series of controlled base excitations to stamens mounted as cantilever beams in an electrodynamic shaker to measure their mechanical properties, and then we determine what effect, if any, different excitation frequencies and accelerations have on pollen release. Finally, we evaluate the generality of our laboratory results using field observations of P. lanceolata under turbulent conditions in a meadow.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Biology of Plantago lanceolata

Plantago lanceolata (Plantaginaceae) is a cosmopolitan perennial herb that is found in mid- to high latitudes [19]. It produces a 2- to 8-cm long conical or cylindrical spike inflorescence on leafless scapes that extend up to 60 cm from a 3–40 cm basal diameter rosette. Although it is gynodioecious [20], only hermaphrodites are examined here. The flowers are arranged spirally along the longitudinal axis of the spike at an angle of 60° [21]. Each flower is approximately 3 mm in length and symmetrical in both axes with a centred pistil and four evenly spaced filaments [21]. As with many wind-pollinated plants, the corolla is severely reduced with respect to the length of the filaments [22]. Two pollen lobes are joined to form a heart-shaped anther that hangs from a slender, horizontally exserted filament about 6 mm in length. The anther is versatile with respect to the filament and rotates or flaps freely at its end. Anther dehiscence is lengthwise at opposite ends [20]. Refer to [9] for detailed stamen micrographs. Anthers are interspersed with sticky pollenkitt which causes pollen to disperse in clumps [23]. Pollen production per anther is varied with accounts ranging from 11 908 ± 262.2 (average ± s.d.) grains [24] to as many as 20 500 ± 2200 [20]. On average, each grain has a mass of 14.4 × 10−9 g and a diameter of 23 × 10−6 m [8].

2.2. Characterization of the stamen mechanical properties

Specimens of P. lanceolata were grown in a growth chamber from seeds obtained from Horizon Herbs (Williams, OR, USA). On flowering, plants were transferred into a 21°C, 50–60% relative humidity laboratory, underneath a timer-controlled fluorescent lamp programmed at 16-h daylight intervals. Stamens with fully extended filaments and undehisced anthers were selected for mechanical testing. The use of non-ruptured anthers ensured that there was no pollen lost prior to and during the experiment, which may have compromised the results. This also represented a boundary limit where the potential for pollen release was maximized. Between 8.00 and 9.00 (local time), when undehiscent stamens were most abundant, a flower from a group of 30 plants was removed from an inflorescence using fine-tipped tweezers. The flower was then embedded at its base in an adhesive (Lepage FunTak, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and mounted horizontally at the edge of an aluminium circular plate that was fixed to a vertically oriented SmartShaker Pro K2004E01 electrodynamic shaker (The Modal Shop, Cincinnati, OH, USA; figure 1a). Using tweezers, all but one stamen and the pistil were removed from the flower. The flower was discarded if any part of the procedure was thought to cause damage to the remaining stamen. To measure the dynamic properties of the stamen, a 4003A function generator (BK Precision, Yorba Linda, CA, USA) excited the electrodynamic shaker in the vertical plane, with a low-amplitude sinusoidal signal that increased from 8 to 42 Hz over a period of 5 s. Vertically oriented vibrations were chosen because the largest amplitude displacements were observed to occur predominantly along the vertical axis. The frequency range was based on preliminary observations that indicated that resonance of the stamen was likely to occur within this frequency range. The amplitude of the excitations was just high enough to observe motion outside of resonance. The excitations were filmed through a Canon macrolens fixed to a Casio Elixim FH25 digital camera focused perpendicular to the stamen. The video was recorded at 120 frames per second (fps). A Phidget 1049 accelerometer (Phidgets Inc., Calgary, Alberta, Canada) attached to the electrodynamic shaker captured its motion at 500 samples per second. Each stamen was vibrated for a total of 15 s (equivalent to three frequency sweep periods). The displacement time series for the motion of the stamen was generated using Tracker Video Analysis and Modeling software (Open Source Physics, http://www.compadre.org/osp/). The frequency spectrum of the stamen displacement was obtained by fast Fourier transform in Originpro v. 8.6.0 Sr2 (OriginLabs, Northampton, MA, USA). The first mode in the spectrum was taken as the natural frequency, fn. The damping ratio was found by the half-power bandwidth method, ξ = (f+ − f−)/2fn, where f+ and f− correspond to the frequencies on either side of the first mode where the amplitude has decreased to  times its maximum value (figure 1b, main frame) [25]. Immediately following harmonic testing, the anther was plucked from the filament and placed in a preweighed 0.2 ml microcentrifuge tube. The unloaded filament, reflexed upwards and became straight. The difference in its displacement or deflection, s0, was measured in ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA) from still images taken before and after the manipulation. The microcentrifuge tube was weighed on a Mettler Toledo AX205 microbalance (sensitivity 0.01 mg) and the mass of the anther, ma, was determined by the difference method. The filament length, L, and diameter, d, were measured under light microscopy. The flexural rigidity of the filament, EI, was obtained using the cantilever-beam model, EI = magL/3s0, with g being the gravitational acceleration [26].

times its maximum value (figure 1b, main frame) [25]. Immediately following harmonic testing, the anther was plucked from the filament and placed in a preweighed 0.2 ml microcentrifuge tube. The unloaded filament, reflexed upwards and became straight. The difference in its displacement or deflection, s0, was measured in ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA) from still images taken before and after the manipulation. The microcentrifuge tube was weighed on a Mettler Toledo AX205 microbalance (sensitivity 0.01 mg) and the mass of the anther, ma, was determined by the difference method. The filament length, L, and diameter, d, were measured under light microscopy. The flexural rigidity of the filament, EI, was obtained using the cantilever-beam model, EI = magL/3s0, with g being the gravitational acceleration [26].

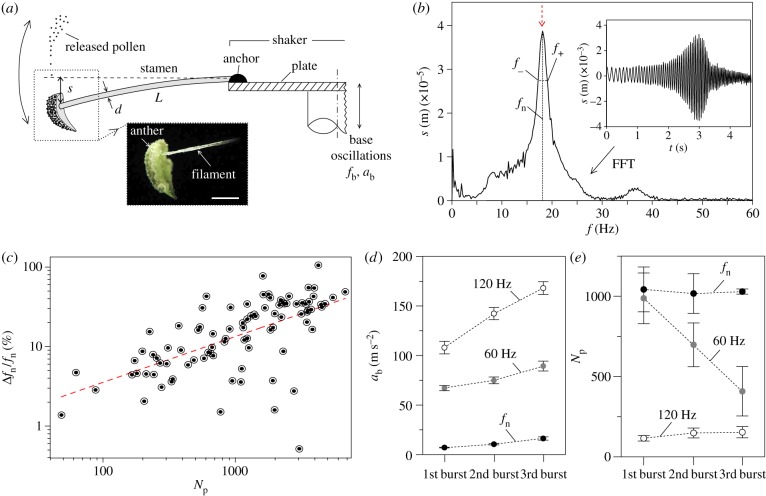

Figure 1.

Results obtained in laboratory experiments. (a) Schematic of the experimental set-up for laboratory measurements of the mechanical properties of stamens, including a photograph of a sample used in the tests (inset; scale bar, 1 mm). (b) Sample time series of the anther displacement during a frequency sweep in the electrodynamic shaker (inset), and corresponding fast Fourier transform (main frame), with red dashed arrow indicating resonance condition. (c) Relative increments of the measured resonance frequency as a function of the number of pollen grains released after a single burst, including a linear regression model (dashed red line). (d) RMS vertical acceleration of the plate at three consecutive bursts, with base frequency tuned to 120 Hz (white dots), 60 Hz (grey dots) and to the natural frequency (black dots). (e) Recorded number of pollen grains shed at three consecutive bursts with base frequency tuned to 120 Hz (white dots), 60 Hz (grey dots) and to the natural frequency (black dots). Error bars represent the standard deviation. (Online version in colour.)

2.3. Pollen shedding under base excitations

The minimum acceleration required for pollen release was determined for newly dehisced stamens using different excitation frequencies. Stamens were excited repeatedly to determine whether there was variation in the pollen release threshold and in the amount of pollen released. Stamens were mounted on the electrodynamic shaker using the procedure described above. Pollen was not displaced during the mounting procedure; otherwise the flower was discarded. To test the hypotheses that the acceleration required for inertial pollen release depends on the frequency of vibration, 50 stamens were excited in the vertical plane either at their natural frequency, at 60 Hz or at 120 Hz (figure 1a). The stamens were excited initially through a series of increasing frequencies and at very low amplitude to prevent pollen release. The natural frequency was re-evaluated whenever pollen release was observed. The excitation acceleration at the time of release was measured using the Phidget 1049 accelerometer for resonance excitations, and a SEN09332 adxl 193 accelerometer (SparkFun Electronics, Boulder, CO, USA) was used at higher frequency. For each treatment, a microscope slide coated with a thin layer of glycerin lubricant was held at a 45° angle at 1 cm from the anther to retain pollen. The excitation amplitude was then increased and muted when pollen was ejected from the anther onto the slide. In order to test the null hypotheses that there is only a single acceleration threshold, the procedure was repeated a maximum of three sequential bursts. Multiple bursts were not pursued since stamens could only be tested within the shaker's frequency-specific acceleration tolerances. The pollen slides were then examined under light microscopy and the number of grains ejected per burst was counted.

2.4. Pollen shedding in field observations

Naturally occurring specimens of P. lanceolata were observed in the northwest section of a mowed field from 10 to 11 September 2012 at Delaware, Ontario, CA (42°55′ N, 81°24′ W, 224 m.a.s.l). The section had only been mowed once in early summer and consisted of the focal species, long grasses and approximately 1 m high shrubs. The northern and western perimeters of the section were sheltered by a mixture of coniferous and deciduous trees ranging in height from 4 to 15 m. An 81 000 ultrasonic anemometer (R.M. Young, Traverse City, MI, USA) was positioned on a tripod at a height of 2.0 m at the centre of the section. Orthogonal wind velocity measurements in three axes (u, v and w) and temperature were sampled digitally by a SmartReader Plus 7 data logger (ACR Systems, Surrey, British Columbia, Canada) at a frequency of 25 Hz. The +v direction was north-facing and represented the horizontal datum (0°), whereas the +u and +w directions were west and upfacing, respectively. Stamens were filmed using the high-speed camera system described above (Casio Elixim FH25 digital camera with sampling frequency 120 Hz), using the inbuilt 20× zoom lens. Each specimen was located within a horizontal radius of 2.0 m from the anemometer. Specimens were selected based on whether or not it was convenient to film in their vicinity. Selected plants were not adjacent to any shrubs or long grasses. Using a wind vane located in one corner of the section, the camera and tripod were positioned downwind of a focal plant to minimize interference with the flow, and at least 20.0 cm from the stamen. The camera was positioned as close to the stamens as possible so that at least one stamen was in focus. To prevent the wind from moving the stamens out of focus, the scape was fixed to a thin wooden stake using masking tape, 2.0 cm below the spike. Most of the plants observed had fully extended stamens by 9.00 and were usually covered in dew. The moisture evaporated quickly and dehiscence soon followed. By noon, the vast majority of stamens had dehisced and was mostly depleted of pollen. However, the filaments maintained their turgor well into the afternoon, which is similar to what was observed in the laboratory. Between 10.00 and 24.00, stamens were filmed and wind velocity was sampled over 9-min intervals (table 1). Later, videos were separated for processing into 1 min segments, and displacement time series were produced for the single most visible stamen in each video using the video analysis method described above. As with the laboratory experiments, stamens were observed to move predominantly in the vertical axis, which was the only direction of motion considered in the analysis. Fluctuations in wind velocity (u′, v′, w′) were calculated using the formula  , where x is the instantaneous measurement and

, where x is the instantaneous measurement and  is the time-averaged value. Fourier analysis was used to evaluate the temporal periodicity and frequency distribution of energy for the fluctuations. Power spectral densities (PSDs) were generated via the periodogram method with a Hanning window in OriginPro v. 8.6.0 Sr2 up to a Nyquist frequency of 60 Hz for stamen displacements and 12.5 Hz for wind velocities. The acceleration PSD was computed directly from the displacement PSD using Parseval's theorem [9,25].

is the time-averaged value. Fourier analysis was used to evaluate the temporal periodicity and frequency distribution of energy for the fluctuations. Power spectral densities (PSDs) were generated via the periodogram method with a Hanning window in OriginPro v. 8.6.0 Sr2 up to a Nyquist frequency of 60 Hz for stamen displacements and 12.5 Hz for wind velocities. The acceleration PSD was computed directly from the displacement PSD using Parseval's theorem [9,25].

Table 1.

Summary statistics from field observations. I, II, III: Refers to a unique stamen and its sampling interval (local time). H, stamen height (m); T, temperature (°C); Θ, clockwise angle with respect to north (deg.).  , average wind speed (m/s); TI, turbulence intensity. uRMS, vRMS, wRMS, root mean square of wind velocity in x-, y-, and z-directions (m s−1), respectively.

, average wind speed (m/s); TI, turbulence intensity. uRMS, vRMS, wRMS, root mean square of wind velocity in x-, y-, and z-directions (m s−1), respectively.

| stamen ID/sampling interval | date and time | stamen |

average conditions |

turbulent conditions |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | T | Θ |  |

TI | uRMS | vRMS | wRMS | ||

| I | 11 Sep 2012, 11.30 | 0.16 | 21.5 ± 0.62 | 179 ± 132 | 1.25 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.95 | 0.40 |

| II | 11 Sep 2012, 10.52 | 0.29 | 20.6 ± 0.45 | 162 ± 134 | 1.06 | 0.58 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.37 |

| III | 10 Sep 2012, 12.46 | 0.27 | 18.5 ± 0.92 | 171 ± 139 | 0.88 | 0.59 | 0.74 | 0.61 | 0.26 |

3. Results

3.1. Laboratory experiments

A set of time-varying sinusoidal base excitations, characterized by a frequency, fb, and vertical acceleration, ab, were applied to stamens mounted horizontally on an electrodynamic shaker (figure 1a). The oscillations caused stamens to vibrate in the vertical axis with increasing frequency and amplitude to a maximum followed by relaxation, indicating a strong resonant response (figure 1b, inset). Stamens resonated at fn = 20.0 ± 4.0 Hz (average ± s.d.; n = 45) as indicated by their displacement spectral response (figure 1b, main frame). The small damping ratio inferred from the displacement spectra, ξ = 0.051 ± 0.009, indicated strongly underdamped oscillations. In addition, the stamens had a static vertical deflection s0 = 1.0 ± 0.4 × 10−3 m caused by gravitational acceleration. Removing individual anthers from the filaments and weighing them provided an anther mass ma = 3.2 ± 0.8 × 10−7 kg, which is considerably larger than the filament mass [9]. The length and diameter of the filaments were L = 6.5 ± 1.0 × 10−3 m and d = 0.095 ± 0.012 × 10−3 m, respectively. Based on these results, the flexural rigidity EI = 3.0 ± 2.0 × 10−10 Nm2 was computed using a cantilever-beam model (see Material and methods).

Pollen was released from newly dehisced anthers in multiple discrete bursts rather than in a continuous manner. At resonance, these events were preceded by a slight elliptical twisting motion of the filament in the vertical axis that was notable only at high accelerations. For all frequencies, there was shaking (e.g. rotation and tilt) of the anther that had no notable periodicity. This motion began slightly before pollen release and became increasingly dramatic in amplitude until release.

The natural frequency of vibration always increased after pollen release events, to a maximum of 65 Hz when pollen in the anther was exhausted. In fact, the relative increase in frequency, Δfn/fn, was significantly correlated with the total number of pollen grains, Np, released after a sequence of three bursts (r = 0.61, F1,89 = 53.3, p < 0.001) (figure 1c).

Vibration of newly dehisced anthers indicated that the acceleration required for pollen release always increased after each burst regardless of the base-excitation frequency dialled on the shaker (figure 1d). Furthermore, vibrations near resonance led to large reductions in the input acceleration required for pollen release and to increasingly larger amounts of pollen released (figure 1d–e). On average, increasing base frequencies resulted in smaller amounts of pollen released, with pollen release events requiring increasingly larger accelerations (figure 1d–e).

3.2. Field observations

Displacement time series were generated from high-speed video taken in the field of three stamens (referred to as stamens I, II and III) from different P. lanceolata plants. Visualizations of the high-speed video snapshots revealed rapid oscillations of the stamens and discrete pollen bursts. This phenomenon is documented in figure 2a, in which an anther can be seen rapidly moving from left to right, twisting upon return to the left and then releasing pollen in the last frame (additional pollen release events are shown in the electronic supplementary material, movie S1). Summary statistics of the corresponding meteorological conditions are provided in table 1. Stamens I and II corresponded to dehisced stamens with about half their pollen remaining, whereas stamen III was undehisced prior to measurements.

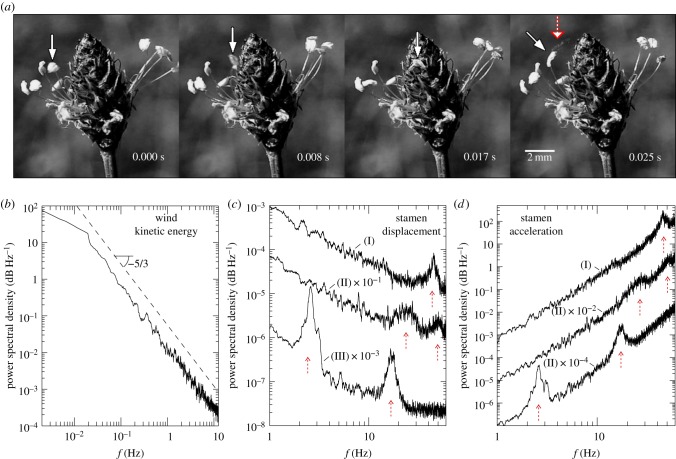

Figure 2.

Results obtained in field experiments. (a) Sequential high-speed images from field observations of stamen II (white solid arrow), including a pollen release event (red/white dashed arrow). (b) Averaged frequency spectrum of the wind turbulent kinetic energy. Also included are PSDs of (c) the displacement and (d) acceleration of stamens I, II and III, including approximate resonance conditions (red dashed arrows). (Online version in colour.)

Wind conditions did not vary greatly between directions or sampling intervals for these field observations. The average wind speed was always below 1.0 m s−1 with turbulence intensity (variance to mean ratio) on the order of 60%. The slope of the averaged spectrum of the wind turbulent kinetic energy (figure 2b) matches closely with Kolmogorov's −5/3 scaling [27].

The plots of the PSD of the stamen displacement show that the greatest amplitude displacements were generally associated with low-frequency oscillations (figure 2c). However, despite the overall decline of the wind turbulent kinetic energy with frequency (figure 2b), the displacement spectral response had coherent peaks at high frequencies (figure 2c, red arrows). In particular, stamens I and III had narrow spikes in the displacement spectra at 45.1 and 16.5 Hz, respectively, whereas stamen II had wider spikes at 26.7 and 56.5 Hz (figure 2c, dashed arrows). Unlike the other stamens, stamen III had two large peaks, the first reaching a maximum at 2.6 Hz and the second at 16.5 Hz. Further analysis revealed that the peak at 2.6 Hz corresponded to the bulk motion of the inflorescence as was seen in the spectra of the fluctuations in inflorescence displacement where only one peak was observed.

Large displacement amplitudes alone may not cause pollen shedding, particularly if they are associated with small anther accelerations. However, analyses of the PSDs of the stamen acceleration showed that the acceleration amplitude increased with frequency in the measured range. Furthermore, the acceleration PSDs displayed order-of-magnitude increases in spectral space that occurred at frequencies corresponding to peaks in the displacement PSDs (figure 2d, dashed arrows).

The spikes in the spectral responses of the stamen displacement and acceleration were correlated with pollen release events induced by the turbulent wind. For instance, the high-speed images (figure 2a, dashed arrow in right-hand-most panel) show that pollen release occurred from stamen II after approximately one complete oscillation (e.g. within the spatio-temporal resolution of the video-acquisition system), whose characteristic amplitude Δs ∼ 0.0010–0.0015 m and period Δt ∼ 0.020–0.025 s yield a characteristic RMS acceleration of order  ∼ 60–100 m s−2 at f ∼ 40–50 Hz, which corresponds roughly to the second peak in the stamen spectral response (figure 2c–d; electronic supplementary material, movie S1).

∼ 60–100 m s−2 at f ∼ 40–50 Hz, which corresponds roughly to the second peak in the stamen spectral response (figure 2c–d; electronic supplementary material, movie S1).

4. Discussion

The laboratory experiments showed that pollen ejections occurred episodically regardless of the excitation frequency. Resonant excitations maximized the number of grains released and minimized the excitation acceleration required to release pollen (figure 1b–d). The specific mechanical properties of the P. lanceolata stamens, including the natural frequencies, fn, damping ratios, ξ, and flexural rigidities, EI, were consistent with the theoretical ranges predicted to generate resonance vibrations by turbulent excitations [8]. Importantly, stamens vibrating at resonance frequencies similar to those obtained from the laboratory experiments, and shedding pollen during resonance, were observed under natural conditions in the field (figure 2a,c–d). The commonness of wind-pollinated stamen characteristics such as exsertion and a high ratio of length to width [1], suggests that turbulence-driven pollen release due to resonant vibration may be the typical shedding mechanism for most angiosperms.

Our observations show that there are two features that can be associated with a resonance-based mechanism for pollen release. First, the resonance frequency of the stamen increased temporally as the anther mass lessened after each episode of pollen shedding, with increasingly larger inputs of mechanical energy needed to trigger a subsequent pollen release event (figure 1d). Second, although the kinetic energy of the wind decreased with frequency, the turbulent eddies whose turnover periods were near the resonance frequency (f ∼ fn) are likely the most effective ones in transferring their kinetic energy into stamen vibrations. This effect can be understood qualitatively by expressing the stamen motion with the dynamic equilibrium equation for a single degree-of-freedom linear oscillator subject to stochastic forcing, which yields qualitatively similar trends in spectral space as those observed in the experiments (figure 1b). According to this model, the stamen structure behaves as a narrow band-pass filter in spectral space that is most receptive to near-resonance forcing [9]. Indeed, near-resonance aerodynamic excitations translate into 10-fold increases in the number of pollen grains released (figure 1e) and in PSDs of stamen displacements and accelerations (figure 2c–d). By contrast, the aerodynamic forces caused by large-size or low-frequency turbulent eddies ( ), which move with large kinetic energies, caused negligible accelerations (figure 2c), whereas very small or high-frequency eddies (

), which move with large kinetic energies, caused negligible accelerations (figure 2c), whereas very small or high-frequency eddies ( ) (which are beyond the spatio-temporal resolution of the instrumentations used here) are dominated by viscosity and could not produce any coherent motion of the stamen.

) (which are beyond the spatio-temporal resolution of the instrumentations used here) are dominated by viscosity and could not produce any coherent motion of the stamen.

Typical values of stamen resonance frequencies are well within the inertial subrange in the turbulence cascade (figure 2b), in a region where the relevant eddies (f ∼ fn) still have sufficient kinetic energy to convert into stamen vibrations before viscous dissipation dominates. In fact, the characteristic Reynolds numbers (ratio of inertial to viscous forces) of stamens, which are of order 1–10 (based on average filament diameters) or 100–1000 (based on average anther sizes or filament lengths) [9], indicate that the surrounding fluid motion can, potentially, transfer mechanical energy to the stamens because of the predominant inertial effects. In addition, the particularly low value of the damping ratio ξ ∼ 0.05 of P. lanceolata is of interest as it enables large amplitudes at resonance, which would otherwise be dissipated rapidly by viscous drag and internal friction.

While similar aeroelastic phenomena have been studied in plant stems, e.g. stem buckling in herbaceous crops [28,29], or seta vibrations leading to spore release in the bryophyte Atrichum undulatum [30], to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show that resonant vibration leads to enhanced release of pollen in a wind-pollinated plant. Unfortunately, there are few studies of the elastic properties of stamens, most of which are limited to bee-pollinated systems involving buzz-pollination whereby pollen is liberated by the bee-induced plant vibrations (e.g. [31]). Those studies reported values of natural frequencies in the range fn ∼ 10–100 Hz, damping ratios of order ξ ∼ 0.1 and flexural rigidities of order EI ∼ 10−7 Nm2 [26,32–34], which is a broader range of fn, and larger values of ξ and EI than we determined for the wind-pollinated P. lanceolata. Based on these differences, we propose that lower values of stamen ξ and EI, which would maximize acceleration amplitudes, should be more common in wind-pollinated angiosperms using the resonant vibration pollen release mechanism compared with those of animal-pollinated species. The observation of pollen release, in both the laboratory and the field, in discrete multiple bursts of increasing frequency support this concept (figures 1d and 2a). Moreover, as animal-pollinated plants must retain the pollen available for pollinators, these plant species should have (i) damping and slenderness values that preclude a wind-induced resonant response, (ii) sticky pollen grains that resist stamen accelerations and instead adhere to the hairs or feathers of pollinators and (iii) have mechanisms to minimize the ambient turbulence (e.g. tubular corollas), thus reducing the vibration response in the range where ambient turbulent fluctuations are relevant.

The incomplete release of pollen during the initial burst suggests that there is intra-anther variation in the forces resisting the acceleration of the grains. Although there is only a rudimentary understanding of these forces in anthers, it is possible that the intra-granular tapetum-derived adhesives (e.g. pollen glues such as pollenkitt), more typical of animal-pollinated plants, play a role in the rate of pollen release in P. lanceolata. Similarly, multiple bursts of pollen from stamens were found in the buzz-pollinated Actinidia deliciosa [33,35] due to intra-anther variation in the distribution of pollen glues, as well as the severance of interstitial bridges of pollen glue during vibration [32]. Conversely, given that most species release pollen or spores during dry weather (i.e. low relative humidity) [8], variations in resistance to accelerations may be driven by differential dehydration, with more exposed pollen (i.e. grains near the stomium) drying more quickly because of a stronger moisture gradient in the vicinity of the ambient air than those near the locular wall. This mechanism would be consistent with the well-known correlation of anther dehiscence and ambient pollen concentration with relative humidity [35,36]. We note that with A. deliciosa, the quantity of tapetal fluid decreases with time since dehiscence as evaporation proceeds [34]. In addition, there may be other important forms of pollen adhesion and cohesion in wind-pollinated plants (e.g. mechanical interlocking, electrostatic and van der Waals forces) responsible for this variation [37].

There remain many unanswered questions regarding the process of pollen liberation. Further studies should, for example, investigate the effects of varying meteorological conditions, such as turbulence intensity or relative humidity, on the strength of resistive forces and on the rate of pollen release. Similarly, more complex laboratory models should incorporate the full three-dimensional motion of the stamen and the facts that (i) the stamen is not an isolated structure but is coupled to the motion of the rest of the plant in a complex manner (c.f. figure 2c–d, first peak in spectral response of stamen III) and (ii) that the filament is composed of porous tissue that is influenced by internal fluid transport. Finally, stamen biomechanics should be studied in taxa where there have been independent transitions between the biotic and abiotic pollination systems to ascertain the degree to which natural selection has acted on the vibration pollen release system to promote or hinder the release of pollen by wind.

The classic syndromes of animal- and wind-pollinated plants [38] have tended to be lists of correlative traits supported by conceptual explanations for the adaptive significance of each trait. We propose that a biomechanical approach, focused on accelerative and resistive forces (e.g. [3]), would provide a more productive understanding of the evolutionary ecology of plant reproduction in which theory could drive hypotheses (e.g. the role of a more open corolla or a more slender stamen in the evolutionary transition to or from wind pollination). The physical ecology approach has the potential to provide meaningful insight into the evolutionary ecology of plants [1].

Acknowledgements

We thank Dan Juras, Scott Monk, Sonia Ruiz and Richard Allix for technical assistance, Geoffrey Fissore for assisting with the laboratory experiments, Circle R. Ranch for providing access to the field site and two anonymous reviewers for providing valuable comments. This is CANPOLIN publication number 122.

Funding statement

We acknowledge the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada through Discovery Grants to D.F.G. and J.D.A. and a PGS-M scholarship to D.T., and the Canadian Pollination Initiative for their generous financial support; the Ibercaja Foundation at Zaragoza (Spain) supported J.U. through a Postdoctoral Fellowship for Excellence in Research award.

References

- 1.Ackerman JD. 2000. Abiotic pollen and pollination: ecological, functional, and evolutionary perspectives. Plant Syst. Evol. 222, 167–185. ( 10.1007/BF00984101) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman J, Barrett SCH. 2009. Wind of change: new insights on the ecology and evolution of pollination and mating in wind-pollinated plants. Ann. Bot. 103, 1515–1527. ( 10.1093/aob/mcp035) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timerman D, Greene DF, Ackerman JD, Kevan PG, Nardone E. 2014. Pollen aggregation in relation to pollination vector. Int. J. Plant Sci. 175, 681–687. ( 10.1086/676301) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuparinen A. 2006. Mechanistic models for wind dispersal. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 296–301. ( 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.04.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Culley TM, Weller SG, Sakai AK. 2002. The evolution of wind pollination in angiosperms. Trends Ecol. Evol. 17, 361–369. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02540-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman J, Barrett SCH. 2008. A phylogenetic analysis of the evolution of wind pollination in the angiosperms. Int. J. Plant Sci. 169, 49–58. ( 10.1086/522510) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niklas KJ. 1985. The aerodynamics of wind pollination. Bot. Rev. 51, 328–386. ( 10.1007/BF02861079) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson ST, Lyford ME. 1999. Pollen dispersal models in quaternary plant ecology: assumptions, parameters, and prescriptions. Bot. Rev. 65, 39–75. ( 10.1007/BF02856557) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urzay J, Llewellyn-Smith SG, Thompson E, Glover BJ. 2009. Wind gusts and plant aeroelasticity effects on the aerodynamics of pollen shedding: a hypothetical turbulence-initiated wind-pollination mechanism. J. Theor. Biol. 259, 785–792. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.04.027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hufford LD, Endress PK. 1989. The diversity of anther structures and dehiscence patterns among Hamamelididae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 99, 301–346. ( 10.1111/j.1095-8339.1989.tb00406.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor PE, Card G, House J, Dickinson MH, Flagan RC. 2006. High-speed pollen release in the white mulberry tree, Morus alba L. Sex. Plant Reprod. 19, 19–24. ( 10.1007/s00497-005-0018-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franchi GG, Nepi M, Matthews ML, Pacini E. 2007. Anther opening, pollen biology and stigma receptivity in the long blooming species, Parietaria judaica L. (Urticaceae). Flora 202, 118–127. ( 10.1016/j.flora.2006.03.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin MD, Chamecki M, Brush GS, Meneveau C, Parlange MB. 2009. Pollen clumping and wind dispersal in an invasive angiosperm. Am. J. Bot. 96, 1703–1711. ( 10.3732/ajb.0800407) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabban L, Jacobson N-L, van Hout R. 2012. Measurement of pollen clump release and breakup in the vicinity of ragweed (A. confertiflora) staminate flowers. Ecosphere 3, 1–24. ( 10.1890/ES12-00054.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niklas KJ. 1992. Plant biomechanics: an engineering approach to plant form and function. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman J, Harder LD. 2004. Inflorescence architecture and wind pollination in six grass species. Funct. Ecol. 18, 851–860. ( 10.1111/j.0269-8463.2004.00921.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pozner R, Cocucci A. 2006. Floral structure, anther development, and pollen dispersal of Halophytum ameghinoi (Halophytaceae). Int. J. Plant Sci. 167, 1091–1098. ( 10.1086/508064) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuiper PJC, Bos M. 2011. Plantago: a multidisciplinary study. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavers PB, Bassett IJ, Crompton CW. 1980. The biology of Canadian weeds: 47. Plantago lanceolata L. Can. J. Plant Sci. 60, 1269–1282. ( 10.4141/cjps80-180) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyde HA, Williams DA. 1946. Studies in atmospheric pollen III: pollen production and pollen incidence in ribwort plantain (Plantago lanceolata L). New Phytol. 45, 271–277. ( 10.2307/2429055) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson LB. 1926. Floral anatomy of several species of Plantago. Am. J. Bot. 13, 397–405. ( 10.2307/2435317) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Primack RB. 1978. Evolutionary aspects of wind pollination in the genus Plantago (Plantaginaceae). New Phytol. 81, 449–458. ( 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1978.tb02650.x). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tonsor SJ. 1985. Leptokurtic pollen-flow, non-leptokurtic gene-flow in a wind-pollinated herb, Plantago lanceolata L. Oecologia 67, 442–446. ( 10.1007/BF00384953) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma N, Koul AK, Kaul V. 1999. Pattern of resource allocation of six Plantago species with different breeding systems. J. Plant Res. 112, 1–5. ( 10.1007/PL00013850) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao JS, Gupta DK. 1999. Introductory course on theory and practice of mechanical vibrations. New Delhi, India: New Age International. [Google Scholar]

- 26.King MJ, Buchmann SL. 1995. Bumble bee-initiated vibration release mechanism of Rhododendron pollen. Am. J. Bot. 82, 1407–1411. ( 10.2307/2445867) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyngaard JC. 2010. Turbulence in the atmosphere. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flesch TK, Grant RH. 1992. Corn motion in the wind during senescence: I. Motion characteristics. Agron. J. 84, 742–747. ( 10.2134/agronj1992.00021962008400040037x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sterling M, Baker C, Berry P, Wade A. 2003. An experimental investigation of the lodging of wheat. Agric. For. Meteorol. 119, 149–165. ( 10.1016/S0168-1923(03)00140-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansson V, Lönnell N, Sundberg S, Hylander K. 2014. Release thresholds for moss spores: the importance of turbulence and sporophyte length. J. Ecol. 102, 721–729. ( 10.1111/1365-2745.12245) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchmann SL. 1983. Buzz pollination in angiosperms. In Handbook of experimental pollination biology (eds Jones CE, Little RJ.), pp. 73–113. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold. [Google Scholar]

- 32.King MJ, Lengoc L. 1993. Vibratory pollen collection dynamics. Trans. ASABE 36, 135–140. ( 10.13031/2013.28324) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.King MJ, Buchmann SL. 1996. Sonication dispensing of pollen from Solanum laciniatum flowers. Funct. Ecol. 10, 449–456. ( 10.2307/2389937) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King MJ, Ferguson AM. 1994. Vibratory collection of Actinidia deliciosa (kiwifruit) pollen. Ann. Bot. 74, 479–482. ( 10.1006/anbo.1994.1144) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lisci M, Tanda C, Pacini E. 1994. Pollination ecophysiology of Mercurialis annua L. (Euphorbiaceae), an anemophilous species flowering all year round. Ann. Bot. 74, 125–135. ( 10.1006/anbo.1994.1102) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bianchini M, Pacini E. 1996. Explosive anther dehiscence in Ricinus communis L. involves cell wall modifications and relative humidity. Int. J. Plant Sci. 157, 739–745. ( 10.1086/297397) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhodes M. 2008. Introduction to particle technology. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faegri K, Pijl L. 1966. The principles of pollination ecology. New York, NY: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]