Abstract

Background

This placebo-controlled study assessed the effects of the once-daily inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) fluticasone furoate (FF) and long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) vilanterol (VI) on early and late asthmatic responses (EAR/LAR) and airway hyper-responsiveness (AHR).

Methods

Patients (n = 27) were randomized to FF (100 μg), VI (25 μg), FF/VI (100/25 μg), and placebo for 21 days (four periods). Allergen challenge was performed 1 h post-dose on day 21. AHR was assessed on day 22 using methacholine.

Results

Allergen challenge caused an early change (0–2 h) in minimum forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) of −1.091 l (95% CI: −1.344; −0.837) following placebo therapy; changes were −0.955 l (−1.209; −0.702), −0.826 l (−1.070; −0.581), and −0.614 l (−0.858; −0.370) following VI, FF, or FF/VI therapy, respectively. Treatment differences were significant for all comparisons between therapies. Mean changes in 0–2 h %FEV1 were as follows: −28.05 (placebo), −23.10 (VI), −22.33 (FF), and −16.10 (FF/VI). Following placebo, the late change (4–10 h) in weighted mean FEV1 was −0.466 l (−0.589; −0.343) and −0.298 l (−0.415; −0.181) after VI, and was +0.018 l with both FF/VI (−0.089; 0.124) and FF (−0.089; 0.125). Treatment differences were significant for all comparisons between therapies except FF/VI vs FF. Mean changes in 4–10 h %FEV1 were as follows: −21.08 (placebo), −14.30 (VI), −5.02 (FF), and −5.83 (FF/VI). AHR 24 h after allergen challenge was significantly reduced with FF/VI and FF vs placebo, and FF/VI was superior to either component.

Conclusion

Combined treatment with FF/VI provides additive protection from the EAR relative to its components, significant protection over VI alone from the LAR, and confers sustained protection from hyper-responsiveness 24 h post-dose.

Keywords: allergen challenge, asthma, atopy, inhaled corticosteroid, long-acting beta2-agonist

In sensitized individuals with asthma, the response to inhaled allergen exposure is often evident as a biphasic decline in lung function comprising the early and late asthmatic responses (EAR/LAR) 1,2. The LAR is regarded as the more clinically important response 3. It is also associated with development of nonspecific airway hyper-responsiveness (AHR) 4.

Allergen-provocation is a well-established and highly reproducible clinical challenge model for understanding the mechanisms of asthma and for testing new therapies 5–7. Approximately 60% of asthma patients have signs of concomitant airborne allergies 8 and have a risk of asthma worsening when exposed to allergen 9. Thus, any new medication for asthma should document effects on allergen responses.

This study aimed to determine the effects of the new inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) fluticasone furoate (FF) and the new long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) vilanterol (VI) on the EAR and LAR, when given alone and in combination. Patients with mild asthma who exhibited both EAR and LAR upon allergen challenge were recruited. FF and/or VI were dosed once daily at the doses of 100 μg and 25 μg, respectively, based on previous dose-ranging studies across a range of asthma severities 10–14.

Methods

A detailed description of the challenge methodology is provided in the Supporting Information.

Design

This study used a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, four-way crossover design to compare the effects of inhaled FF/VI 100/25 μg, FF 100 μg, and VI 25 μg on the EAR and LAR induced by allergen challenge in patients with mild asthma in four research centers in Sweden (n = 2), Australia (n = 1), and New Zealand (n = 1), and it was conducted between May 2010 and May 2011. Patients underwent screening to determine eligibility to enter the study (14–42 days prior to first dose), followed by a 14-day run-in period, then four treatment periods comprising 21 days of treatment with FF/VI, FF, VI, and placebo via the ELLIPTA™ (GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK) dry powder inhaler (DPI). Patients were required to take their medication between 8 AM and noon each day, no specific time of dosing was set, but each patient was required to take their medication at the same time for each day of the treatment period. The doses emitted were 92 μg of FF and 22 μg of VI. Each treatment period was separated by a washout period of 21–35 days. Morning dosing was used in this study to ensure that the allergen challenge could be conducted and subsequent spirometry data collected during daylight hours. All patients provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by local institutional review boards (NCT01128595; GSK study code: HZA113126).

Patients

Patients were 18–65 years of age with bronchial asthma diagnosed for ≥6 months prior to screening and were treated with inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) alone. A prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) percent predicted value of >70%, and a methacholine challenge PC20 of <8 mg/ml were required. During screening, or within 1 month of starting the study, patients were required to exhibit a positive wheal and flare reaction (‘skin prick’ test ≥3 mm diameter relative to negative control) to at least one of a panel of airborne allergens (horse, cat, dog, birch tree, six grass mix, and house dust mite [Dermatophagoides Pteronyssinus]). Patients were also required to exhibit an EAR and a LAR during the screening allergen challenge; those with symptomatic hay fever, or those predicted to experience hay fever during days 14–22 of any study period, were excluded. Patients were randomized using a Williams’ Square to one of four crossover treatment sequences, in accordance with a randomization schedule generated by the sponsor using validated internal software (RandAll; GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK). An automated, telephone-based interactive voice response system, RAMOS (GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK), was used by the investigators to register patients and obtain randomized treatment assignments in a blinded manner.

Allergen and methacholine challenges

Patients were challenged with the allergen that produced the greatest reaction on the skin prick test at screening. The allergen challenge was administered 1 h after the final dose of therapy, at the end of each 21-day treatment period. The methacholine challenge was performed approximately 24 h after the allergen challenge was initiated. The rationale for this was twofold: (i) to allow a return to baseline lung function following the allergen challenge and (ii) to assess the effect of therapy on residual AHR, which is known to be associated with the occurrence of the response to allergen 4. Further details of the allergen and methacholine challenges are provided in the Supporting Information.

Spirometry

Spirometry was assessed at screening, pre-dose on day 1, pre- and post-saline inhalation, and then post-allergen challenge at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min, then every 30 min up to 10 h on day 21, and prior to and after methacholine challenge on day 22. Pre-dose FEV1 was required to be >90% of that recorded during screening to enter each treatment period.

Objectives and endpoints

The primary objectives of this study were to (i) assess the effect of FF/VI 100/25 μg on the LAR relative to placebo and (ii) to assess the effect of FF/VI 100/25 μg on the EAR relative to monotherapy with FF 100 μg or VI 25 μg. These were assessed through comparison of the primary endpoints of weighted mean FEV1 and minimum FEV1. For the LAR, values for FF/VI 100/25 μg and placebo were compared 4–10 h post-allergen challenge. For the EAR, values for FF/VI 100/25 μg and FF 100 μg or VI 25 μg were compared 0–2 h post-allergen challenge. Secondary objectives included assessment of the effects of FF 100 μg or VI 25 μg on the LAR relative to placebo; FF/VI 100/25 μg, FF 100 μg, or VI 25 μg on the EAR relative to placebo; FF/VI 100/25 μg, FF 100 μg, or VI 25 μg on AHR (methacholine challenge on day 22) relative to placebo; and FF/VI 100/25 μg on AHR relative to FF 100 μg or VI 25 μg. In addition, the percentage decrease in FEV1 from the post-saline baseline measure on day 21 was assessed, for the LAR and EAR. Adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs (SAEs) were assessed from day 1 onward, until the end of the follow-up period. Clinical laboratory tests and vital signs were assessed during screening, at pre-dose on day 1 and on day 21 of each treatment period prior to the allergen challenge. Twelve-lead ECG measurements were conducted during screening, while a physical examination was conducted during screening and follow-up.

Statistical methods

A sample size of 20 patients was sufficient to provide at least 90% power to detect a 50% attenuation of the LAR as assessed by the difference between FF/VI 100/25 μg and placebo in both minimum and weighted mean FEV1 (4–10 h). Absolute changes from post-saline baseline on day 21 and differences between treatments were determined using a mixed-effects ancova model to calculate differences, in which treatment period, patient (day 1 pre-dose) baseline FEV1, period baseline FEV1, and treatment were fixed effects, and patient was a random effect. Statistical significance of treatment comparisons was determined by the absence of zero from the 95% CI following statistical testing. Methacholine challenge PC20, on day 22, was analyzed using a mixed-effects ancova model. Period and treatment were included as fixed effects and subject as a random effect. PC20 was log-transformed using base 2 to compare doubling-dose differences between treatments.

Results

Study population and demographics

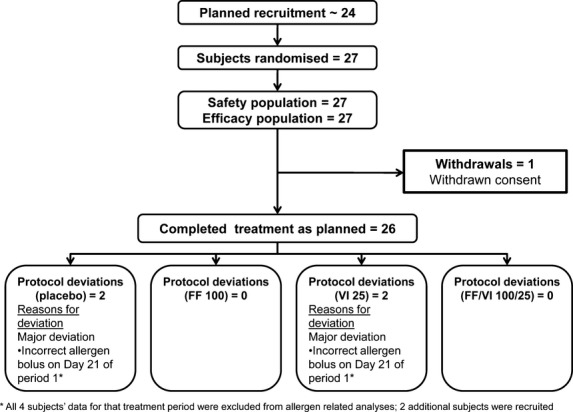

Twenty-seven patients were randomized and 26 completed the study. One patient withdrew consent, and there were four protocol deviations during period 1. Data for those patients were excluded from the analysis of the relevant study periods (Fig. 1). Demographics and baseline lung function are presented in Table 1. Fifteen (56%) patients were challenged with house dust mite, 10 (37%) with cat hair/dander, 1 (4%) with birch pollen, and 1 (4%) with grass pollen.

Figure 1.

CONSORT.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (range) | 30.8 (18–49) |

| Female,% | 30 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (range) | 25.5 (19.2–35.0) |

| White race,% | 93 |

| Lung function: | |

| Pre-bronchodilator FEV1, mean l (range) | 3.7 (2.7–5.0) |

| Pre-bronchodilator FEV1, mean % Pred (range) | 92.3 (71.3–119.8) |

BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

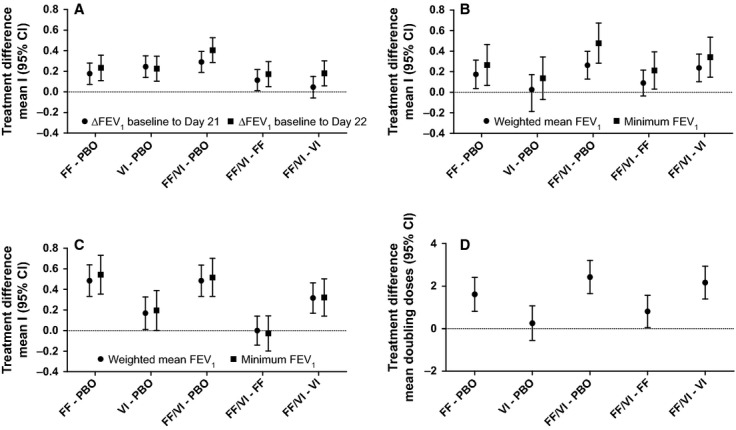

Efficacy

Mean pre-dose FEV1 was similar on day 1 for each treatment period (placebo = 3.67 l; FF/VI = 3.64 l; FF = 3.60 l; VI = 3.62 l). Prior to allergen challenge on day 21, FEV1 declined during placebo treatment and improved with all active treatment (Table 2); treatment differences were significant for all comparisons (as indicated by the absence of zero from 95% CIs) except FF/VI vs VI (Fig. 3A). Prior to the methacholine challenge on day 22 (i.e., approximately 24 h after the last study dose and the allergen challenge), FEV1 continued to be below the day 1 pre-dose measure with placebo therapy (Fig. 2). With FF or VI monotherapy, the day 22 FEV1 was similar to the pre-dose day 1 measure, while with FF/VI therapy, it continued to be elevated compared with the day 1 pre-dose measure (Table 2). At this time point, statistical analysis indicated significant differences for comparisons of each active therapy vs placebo and for FF/VI vs either component (Fig. 3A).

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes by therapy arm

| Parameter | Placebo | FF 100 μg | VI 25 μg | FF/VI 100/25 μg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1: change from pre-dose day 1 to pre-allergen challenge day 21 | ||||

| Adjusted mean, l (95% CI) | −0.061 (−0.147, 0.024) | 0.116 (0.030, 0.202) | 0.183 (0.095, 0.272) | 0.230 (0.145, 0.315) |

| FEV1: change from pre-dose day 1 to pre-methacholine challenge day 22 | ||||

| Adjusted mean, l (95% CI) | −0.203 (−0.298, −0.107) | 0.030 (−0.066, 0.127) | 0.023 (−0.073, 0.119) | 0.203 (0.109, 0.296) |

| EAR (0–2 h post-challenge): change from saline on day 21 | ||||

| Adjusted mean min FEV1, l (95% CI) | −1.091 (−1.344, −0.837) | −0.826 (−1.070, −0.581) | −0.955 (−1.209, −0.702) | −0.614 (−0.858, −0.370) |

| Adjusted mean wm FEV1, l (95% CI) | −0.560 (−0.745, −0.374) | −0.386 (−0.565, −0.207) | −0.533 (−0.718, −0.348) | −0.297 (−0.476, −0.118) |

| Adjusted mean FEV1,% (95% CI) | −28.05 (−35.60, −20.51) | −22.33 (−28.82, −15.85) | −23.10 (−30.27, −15.93) | −16.10 (−22.22, −9.99) |

| LAR (4–10 h post-challenge): change from saline on day 21 | ||||

| Adjusted mean min FEV1, l (95% CI) | −0.731 (−0.878, −0.584) | −0.188 (−0.315, −0.061) | −0.536 (−0.676, −0.396) | −0.216 (−0.343, −0.088) |

| Adjusted mean wm FEV1, l (95% CI) | −0.466 (−0.589, −0.343) | 0.018 (−0.089, 0.125) | −0.298 (−0.415, −0.181) | 0.018 (−0.089, 0.124) |

| Adjusted mean FEV1,% (95% CI) | −21.08 (−26.72, −15.44) | −5.02 (−8.34, −1.69) | −14.30 (−18.81, −9.78) | −5.83 (−9.30, −2.37) |

| Methacholine challenge: day 22 | ||||

| Geometric mean PC20 concentration, mg/ml (95% CI) | 0.191 (0.110, 0.331) | 0.585 (0.342, 1.000) | 0.228 (0.133, 0.393) | 1.028 (0.610, 1.732) |

EAR, early asthmatic response; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FF, fluticasone furoate; LAR, late asthmatic response; VI, vilanterol; wm, weighted mean.

Figure 3.

Mean differences (95% CI) between treatments in outcome: (A) change from baseline in FEV1 (B) EAR minimum and wm FEV1 (C) LAR minimum and wm FEV1 (D) methacholine PC20 doubling doses.

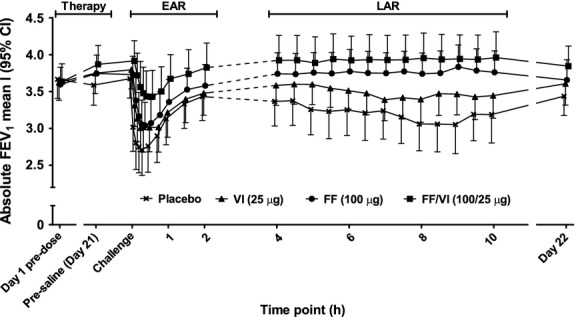

Figure 2.

Absolute FEV1 (mean l [95% CI]) from day 1 to day 21, then over the allergen challenge time course to day 22.

After placebo treatment, allergen challenge caused a biphasic decline in absolute FEV1 (Fig. 2) and percent change in FEV1 (Fig. S1). Comparative time course figures showing differences between active therapy and placebo and FF/VI and its components are shown in Fig. S2. Relative to the EAR observed following placebo, the EAR was reduced following FF, VI, and FF/VI therapy (Table 2); treatment differences are shown in Fig. 3B. Relative to placebo, the LAR was also reduced by all active therapies (Table 2); treatment differences are shown in Fig. 3C. AHR, assessed by methacholine challenge approximately 24 h after allergen challenge, was significantly reduced with FF/VI and FF relative to placebo, while no significant effect was observed with VI treatment relative to placebo. Comparison of FF/VI vs its components showed a significant reduction in AHR for the combination compared with either component alone (Table 2/Fig. 3D).

Safety

The proportion of AEs was 74%, 70%, 85%, and 70% during the FF/VI, FF, VI, and placebo treatment periods, respectively (Table 3). There were no serious AEs, and no patients were withdrawn from the study or discontinued study treatment because of an AE. No clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory findings, ECG readings, or vital signs occurred in patients receiving active treatment during this study.

Table 3.

Treatment-related adverse events

| N (%) | Placebo (n = 27) | FF 100 μg (n = 27) | VI 25 μg (n = 27) | FF/VI 100/25 μg (n = 27) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 7 (26) | 5 (19) | 4 (15) | 6 (22) |

| Headache | 4 (15) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 4 (15) |

| Oral candidiasis | 2 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 0 | 2 (7) |

| Throat irritation | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Dry throat | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspepsia | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Nausea | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oral herpes | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Pharyngitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

AE, adverse event; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FF, fluticasone furoate; VI, vilanterol.

Discussion

This crossover, double-blind study is the first to compare the effects of once-daily regular treatment with FF/VI 100/25 μg and its components on allergen-induced asthma. FF reduced the EAR, LAR, and AHR, while addition of VI to FF further reduced the allergen-induced EAR and AHR 24 h after the allergen provocation.

ICS is effective in allergic asthma 15, and this study establishes the efficacy of FF in attenuating the EAR, LAR, and AHR in allergic asthma patients. The attenuation of EAR and LAR observed with FF in the present study, in which the allergen challenge was initiated 1 h post-dose, is comparable in % terms with those described for other ICS at clinical doses 6,16. The effects of ICS on allergen-induced inflammation and its consequent effect on lung function in asthma are generally ascribed to effects on mast cells 17, eosinophilic inflammation 4,18, and pro-inflammatory T-lymphocytes 19. These effects may have contributed to the mechanisms through which FF attenuated the allergic response in the current study; however, such an effect of FF cannot be confirmed by the current study, as inflammatory markers such as sputum eosinophil levels were not assessed. Pre-clinical studies have indicated that FF has greater anti-inflammatory effects than fluticasone propionate 8,21,22. Nevertheless, in humans the comparative anti-inflammatory activity of FF vs other ICS remains to be determined, both on allergen-induced asthma and in regular therapy in a real-world setting.

The effects of regular therapy with VI alone were also assessed in this study. VI improved lung function in patients with mild allergic asthma following 21 days of therapy and significantly attenuated the LAR, but exhibited a nonsignificant effect on the EAR. These effects are most likely due to a direct bronchodilatory effect of VI, as has been described in other LABA/ICS allergen challenge studies 7,23 and in a prior lung function study of VI 13. Importantly, it must be considered that despite these findings, monotherapy with a LABA is not recommended in asthma 15.

Combining FF and VI resulted in additional attenuation of the EAR over that observed with either therapy alone, most likely as a consequence of the different mechanisms involved. VI did not add to the inhibition of the LAR vs FF, which may be explained by FF therapy alone resulting in a small increase in lung function during the LAR, thus allowing little possibility to detect further improvements. Finally, addition of VI to FF did result in greater protection from methacholine responsiveness 24 h after allergen provocation and the last dose of drug therapy relative to FF alone. Together, these data confirm that FF/VI exhibits efficacy 24 h after the previous dose and provides additional protection to AHR compared with FF or VI alone. It is conceivable that part of the effect of FF/VI on the AHR is related to a reduced inflammatory response following exposure to allergen, which is maintained to some extent approximately 24 h post-dose.

As the response to experimental and environmental inhaled aeroallergens is associated with both bronchoconstriction and activation of the immune system 1, it follows that maximal protection from the clinical response may be achieved by targeting both these features. Indeed, both the VI and FF components show efficacy in the current study, suggesting a benefit of both ICS and bronchodilators in allergen-induced asthma. Furthermore, the combined protective effects of VI and FF on AHR again support the concept that both pharmacological entities contribute to the benefit of the combination. This is of potential clinical relevance to the patient, as an acute decline in lung function of approximately 37% is perceived as a 10-fold increase in breathlessness 24. It is thus conceivable that therapies that limit the acute effects of the EAR and the more long-term effects of the LAR (i.e., development of AHR) could limit the detrimental effects of exposure to aeroallergens in sensitized asthma patients.

AEs, whether drug related or not, were similar when patients received placebo or active treatment. No significant steroid-mediated side-effects were reported when patients received FF, nor were any significant LABA-mediated effects reported when patients received VI.

In the present study, the allergen challenge was conducted shortly after the final dose of therapy, and the sustained protection from the allergic response provided by FF and/or VI at longer time points after dosing was thus not assessed. However, a separate study evaluating the EAR only has shown efficacy of FF/VI and FF when the allergen challenge was performed 23 h after the last dose of regular therapy 25. In the current study, we followed lung function up to 10 h, followed by measurements at 24 h. However, at the 10-h time point, some degree of LAR was still ongoing, and additional measurements could have provided more detailed information on the time course of the effects of FF, VI, and FF/VI on the LAR. Additionally, no allergen ‘vehicle’ provocation was conducted as a comparator for normal lung function over the period of the allergen challenge, nor was a challenge conducted after a shorter period of dosing (e.g., 1 day), which could have determined whether the bronchoprotection afforded by FF/VI is immediate or cumulative. Therefore, additional studies are needed to fully understand the time course of the effect of FF/VI, as well as the biologic mechanisms by which the effects on the allergic response are asserted.

This study shows that combining FF and VI efficiently reduces the response to inhaled allergen in patients with mild allergic asthma. The data further suggest that the effect of a combination of ICS and LABA is mediated through additive effects on the different components of the allergic asthma response. Thus, both FF and VI have protective effects on the asthmatic response, and combining them reduces the response further than either of the drugs alone. Together, these results demonstrate that the combination of FF and VI can be effective in patients with allergic components in their asthma. Whether this once-daily regimen approach leads to increased adherence and greater effectiveness remains to be proven in prospective real-life studies.

Acknowledgments

Maurice Leonard, a former GlaxoSmithKline employee, contributed to the design and played a key role in study setup. Editorial support in the form of development of draft outline, development of manuscript first draft, editorial suggestions to draft versions of this manuscript, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, copyediting, fact checking, referencing, and graphic services was provided by Geoff Weller, PhD at Gardiner-Caldwell Communications (Macclesfield, UK) and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Author contributions

A.O. designed the study and analyzed data; L.B. designed the study and collected data; D.Q. designed the study and collected data; P.S. conducted statistical analysis of the data; P.T. designed the study and collected data; K.Y. managed the study; J.L. designed the study and collected data. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript and approved the final draft for submission.

Conflict of interest

A.O. is an employee of and holds stock/shares in GlaxoSmithKline. L.B. during the last 3 years has received honoraria for speaking and consulting and/or financial support for attending meetings from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Airsonette, Andre Pharma, Boehringer, GlaxoSmithkline, Merck, Mundipharma, Niigard, Novartis, Nycomed/Takeda, and Orion Pharma. D.Q. and P.S. have no conflict of interest to declare. P.T. has served as a consultant to and received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis. K.Y. was employed by GlaxoSmithKline at the time the study was conducted. J.L. has served as a consultant to and received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, Novartis, and UCB Pharma; has been partly covered by some of these companies to attend previous scientific meetings including the ERS and the AAAAI; and has participated in clinical research studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, and Novartis. This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. Mean percent change (95% CI) from post-saline baseline.

Figure S2. (A) Mean differences (95% CI) between active treatments and placebo from day 1 to day 21, over the allergen challenge time course (EAR and LAR) and to pre-methacholine challenge on day 22 for each treatment. (B) Mean differences (95% CI) between combination and components from day 1 to day 21, over the allergen challenge time course (EAR and LAR) and to pre-methacholine challenge on day 22 for each treatment.

Figure S3. The screening allergen challenge.

Figure S4. The bolus allergen challenge and methacholine challenge.

References

- O’Byrne PM. Allergen-induced airway inflammation and its therapeutic intervention. Allergy Asthma Immunol Rev. 2009;1:3–9. doi: 10.4168/aair.2009.1.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockcroft DW, Hargreave FE, O’Byrne PM, Boulet LP. Understanding allergic asthma from allergen inhalation tests. Can Respir J. 2007;14:414–418. doi: 10.1155/2007/753450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Byrne PM, Dolovich J, Hargreave FE. Late asthmatic responses. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:740–751. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.3.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauvreau GM, Evans MY. Allergen inhalation challenge: a human model of asthma exacerbation. Contrib Microbiol. 2007;14:21–32. doi: 10.1159/000107052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman MD, Watson R, Cockroft DW, Wong BJ, Hargreave FE, O’Byrne P. Reproducibility of allergen-induced early and late asthmatic responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95:1191–1195. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauvreau GM, Doctor J, Watson RM, Jordana M, O’Byrne PM. Effects of inhaled budesonide on allergen-induced airway responses and airway inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1267–1271. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.5.8912734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MM, O’Connor TM, Leigh R, Otis J, Gwozd C, Gauvreau GM, et al. Effects of budesonide and formoterol on allergen-induced airway responses, inflammation, and airway remodeling in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lötvall J, Ekerljung L, Rönmark EP, Wennergren G, Lindén A, Rönmark E, et al. West Sweden Asthma Study: prevalence trends over the last 18 years argues no recent increase in asthma. Respir Res. 2009;10:94. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lötvall J, Akdis CA, Bacharier LB, Bjermer L, Casale TB, Custovic A, et al. Asthma endotypes: a new approach to classification of disease entities within the asthma syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse WW, Bleecker ER, Bateman ED, Lötvall J, Forth R, Davis AM, et al. Fluticasone furoate demonstrates efficacy in patients with asthma symptomatic on medium doses of inhaled corticosteroid therapy: an 8-week, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Thorax. 2012;67:35–41. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleecker ER, Bateman ED, Busse W, Lötvall J, Woodcock A, Tomkins S, et al. Fluticasone furoate (FF), an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), is efficacious in asthma patients symptomatic on low doses of ICS therapy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman ED, Bleecker ER, Busse W, Lötvall J, Woodcock A, Forth R, et al. Fluticasone furoate (FF), a once-daily inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), demonstrates dose-response efficacy in patients symptomatic on non-steroidal asthma therapy. Respir Med. 2012;106:642–650. [Google Scholar]

- Lötvall J, Bateman ED, Bleecker ER, Busse W, Woodcock A, Follows R, et al. Dose-related efficacy of vilanterol trifenatate (VI), a long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) with inherent 24-hour activity, in patients with persistent asthma. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:570–579. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00121411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling R, Lim J, Frith L, Snowise NG, Jacques L, Haumann B. Efficacy and optimal dosing interval of the long-acting beta2 agonist, vilanterol, in persistent asthma: a randomised trial. Respir Med. 2012;106:1110–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global initiative for asthma: Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Updated 2011. Available at: http://www.ginasthma.org/. Last Accessed 29 July 2012.

- Inman MD, Watson RM, Rerecich T, Gauvreau GM, Lutsky BN, Stryszak P. Dose-dependent effects of inhaled mometasone furoate on airway function and inflammation after allergen inhalation challenge. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:569–574. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2007063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauvreau GM, Lee JM, Watson RM, Irani AM, Schwartz LB, O’Byrne PM. Increased numbers of both airway basophils and mast cells in sputum after allergen inhalation challenge of atopic asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1473–1478. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9908090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lötvall J, Pamqvist M, Arvisson P. Comparing the effects of two inhaled glucocorticoids on allergen-induced bronchoconstriction and markers of systemic effects, a randomised cross-over double-blind study. Clin Transl Allergy. 2011;1:12. doi: 10.1186/2045-7022-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmhäll C, Bossios A, Pullerits T, Lötvall J. Effects of pollen and nasal glucocorticoid on FOXP3 +, GATA-3 + and T-bet+ cells in allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2007;62:1007–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter M, Biggadike K, Matthews JL, West MR, Haase MV, Farrow SN, et al. Pharmacological properties of the enhanced-affinity glucocorticoid fluticasone furoate in vitro and in an in vivo model of respiratory inflammatory disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:660–667. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00108.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Rossios C, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ, Johnson M. Fluticasone furoate, a novel enhanced-affinity inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), with sustained glucocorticoid receptor nuclear translocation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:A5409. [Google Scholar]

- To M, To Y, Rossios C, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM, Johnson M, et al. Fluticasone furoate, a novel enhanced-affinity inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), has more potent anti-inflammatory effects than fluticasone propionate in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from asthma and COPD patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:A4454. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlén B, Lantz AS, Ihre E, Skedinger M, Henriksson E, Jörgensen L, et al. Effect of formoterol with or without budesonide in repeated low-dose allergen challenge. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:747–753. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00095508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Woude HJ, Boorsma M, Bergqvist PBF, Winter TH, Aalbers R. Budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler rapidly relieves methacholine induced moderate-to-severe bronchoconstriction. Pulm Pharm Ther. 2004;17:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver A, Quinn D, Goldfrad C, van Hecke B, Ayer J, Boyce M. Combined fluticasone furoate/vilanterol reduces decline in lung function following inhaled allergen 23 h after dosing in adult asthma: a randomised, controlled trial. Clin Transl Allergy. 2012;2:11. doi: 10.1186/2045-7022-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Mean percent change (95% CI) from post-saline baseline.

Figure S2. (A) Mean differences (95% CI) between active treatments and placebo from day 1 to day 21, over the allergen challenge time course (EAR and LAR) and to pre-methacholine challenge on day 22 for each treatment. (B) Mean differences (95% CI) between combination and components from day 1 to day 21, over the allergen challenge time course (EAR and LAR) and to pre-methacholine challenge on day 22 for each treatment.

Figure S3. The screening allergen challenge.

Figure S4. The bolus allergen challenge and methacholine challenge.