Abstract

Background

Hereditary angioedema (HAE), caused by deficiency in C1-inhibitor (C1-INH), leads to unpredictable edema of subcutaneous tissues with potentially fatal complications. As surgery can be a trigger for edema episodes, current guidelines recommend preoperative prophylaxis with C1-INH or attenuated androgens in patients with HAE undergoing surgery. However, the risk of an HAE attack in patients without prophylaxis has not been quantified.

Objectives

This analysis examined rates of perioperative edema in patients with HAE not receiving prophylaxis.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of records of randomly selected patients with HAE type I or II treated at the Frankfurt Comprehensive Care Centre. These were examined for information about surgical procedures and the presence of perioperative angioedema.

Results

A total of 331 patients were included; 247 underwent 700 invasive procedures. Of these procedures, 335 were conducted in 144 patients who had not received prophylaxis at the time of surgery. Categories representing significant numbers of procedures were abdominal (n = 113), ENT (n = 71), and gynecological (n = 58) procedures. The rate of documented angioedema without prophylaxis across all procedures was 5.7%; in 24.8% of procedures, the presence of perioperative angioedema could not be excluded, leading to a maximum potential risk of 30.5%. Predictors of perioperative angioedema could not be identified.

Conclusion

The risk of perioperative angioedema in patients with HAE type I or II without prophylaxis undergoing surgical procedures ranged from 5.7% to 30.5% (CI 3.5–35.7%). The unpredictability of HAE episodes supports current international treatment recommendations to consider short-term prophylaxis for all HAE patients undergoing surgery.

Keywords: C1-inhibitor deficiency, hereditary angioedema, HAE, preprocedure prophylaxis, surgical procedures

To cite this article: Aygören-Pürsün E, Martinez Saguer I, Kreuz W, Klingebiel T, Schwabe D. Risk of angioedema following invasive or surgical procedures in HAE type I and II - the natural history. Allergy 2013; 68: 1034–1039.

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a relatively rare autosomal dominant condition caused by a deficiency in C1-inhibitor (C1-INH), the primary control protein for the complement system that regulates vascular permeability 1–3. In 85% of affected patients, the levels of functional C1-INH are low (~30% of normal levels) (HAE-I) 4,5, while 15% of patients have normal or raised levels of nonfunctional C1-INH (HAE-II) 6. C1-INH deficiency results in inappropriate or excessive activation of the complement pathway and allows the activation of kallikrein, which leads to production of the vasoactive peptide bradykinin 2,3.

Clinical symptoms of HAE include edema of the subcutaneous (SC) tissues of the extremities, abdomen, face and larynx 7. Untreated attacks normally last for 3–5 days, and edema of the upper airways is considered life-threatening due to the risk of asphyxiation 5,8. The onset of symptoms typically occurs in childhood, with increased symptoms often seen during puberty, and recurrent attacks occurring throughout life 3. In most cases, HAE attacks are spontaneous in nature, and trigger factors cannot generally be identified, resulting in unpredictable first manifestations and recurrences 1,3–5,9. However, specific trigger factors associated with HAE attacks include oral surgery (including dental work), mechanical stress and exertion, minor injuries and trauma, infections, emotional stress and excitement, insect stings, certain foods and medicines, and menstruation 1,3–5,9–15. Precise trigger factors can vary from patient to patient and even within patients, thus making management of the disorder difficult 1,3–5,9,15.

Due to the increased likelihood of edema posed by emotional stress and physical trauma, surgery and minor manipulations or intubation pose a challenge in patients with HAE. Infusions of plasma-derived or recombinant C1-INH concentrate (Berinert®, CSL Behring; Cinryze®, ViroPharma; and Ruconest™, Swedish Orphan Biovitrum) and subcutaneous (SC) administration of the bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist Icatibant (FIRAZYR®, Shire) have proven effective in the treatment for acute HAE attacks 16–20, while preprocedural infusions of plasma-derived C1-INH can be effective in preventing angioedema associated with dental or surgical procedures 21–23. International 9 and British 4 consensus papers have recommended that administration of prophylactic doses of HAE medication may be advisable under certain circumstances, including during the perioperative period in case of an edema episode. Current guidelines recommend C1-INH for prophylactic use prior to surgery in the first instance 9,24. Where C1-INH is not available, attenuated androgens or antifibrinolytics are recommended as alternatives 9,24.

Although the risk of angioedema associated with surgery or even minor invasive or surgical procedures is well known, no systematic data on the risk of angioedema in patients without prophylaxis have yet been published. Such an analysis could provide evidence to support current recommendations for patients with HAE undergoing surgery.

In this article, we report a single-centre, retrospective analysis of the risk of angioedema in patients with HAE types I and II associated with operative and invasive procedures without preprocedural or concomitant long-term prophylaxis. This analysis of patient records included patients undergoing any surgical procedures, thus reflecting the whole range of routine clinical practice.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of patients with HAE types I and II treated at the Frankfurt Comprehensive Care Centre. The centre has a database of 640 adult and pediatric patients with C1-INH deficiency, from which 331 patients from all ages were randomly selected for assessment. For this analysis, every second patient (in alphabetical order) from the database was selected, thus avoiding potential bias such as severity of HAE. This study focused on surgery without HAE prophylaxis, and patient cases were included irrespective of the year in which the procedure occurred.

Patients’ records were examined for information about type of HAE (I or II), previous procedures, including time and type of procedure, type of prophylaxis if any (preprocedural short-term prophylaxis with C1-INH or long-term prophylaxis with attenuated androgens), number of individual procedures per patient, and presence or absence of perioperative angioedema.

Individual procedures were excluded from further analysis if prior to the procedure the patients were on long-term prophylaxis with attenuated androgens, or if plasma-derived C1-INH had been administered for short-term prophylaxis. No further potential preprocedural prophylactic measures were documented (e.g., use of fresh frozen plasma, antifibrinolytic agents).

Dental procedures were excluded from the analysis to avoid bias as most dental procedures are perceived as relatively minor and are often only reported if adverse events have been experienced. Other exclusion criteria included known HAE type III and acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency. We evaluated the risk of perioperative angioedema in those patients not receiving short- or long-term prophylaxis overall and by type of surgical procedure, using descriptive statistics.

Only procedures with documented angioedema were included in the calculation of minimum risk of an HAE episode, while the sum of this frequency plus the percentage of procedures with unrecorded outcome was used as an estimate for maximum risk. Confidence borders of 2.5% and 97.5% are provided for the minimum risks or the maximum risks, respectively, for the overall population of procedures and some subgroups of subjects and of procedures.

Results

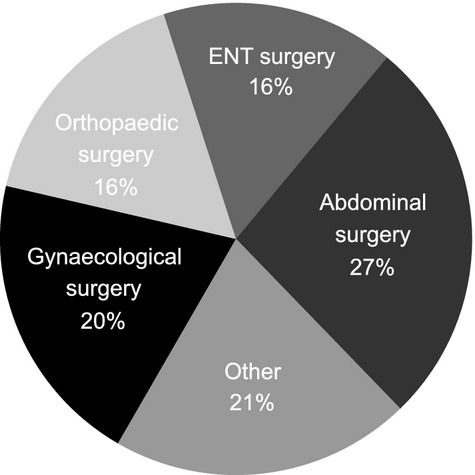

The characteristics of the patients included in this analysis are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients had HAE type I. A total of 331 patients were included, of whom 247 patients (74.6%) underwent a total of 700 invasive procedures (an average of 2.8 procedures per patient). The types of procedures most commonly reported were abdominal (187/700; 26.7%), gynecological (142/700; 20.3%), orthopedic (115/700; 16.4%), or ear, nose, and throat (ENT) (112/700; 16.0%) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Breakdown of patient age, sex, and HAE type

| Patients with procedures | Patients without procedures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 247 | 100% | 84 | 100% |

| HAE-I | 230 | 93% | 78 | 93% |

| HAE-II | 17 | 7% | 6 | 7% |

| Male | 89 | 36% | 37 | 44% |

| Female | 158 | 64% | 47 | 56% |

| Age, y (mean, range) | 43.9 (1–91) | 26.6 (1–80) | ||

| Age <18 years | 23 | 10% | 32 | 38% |

Figure 1.

Types of surgery recorded (both with and without preprocedural prophylaxis).

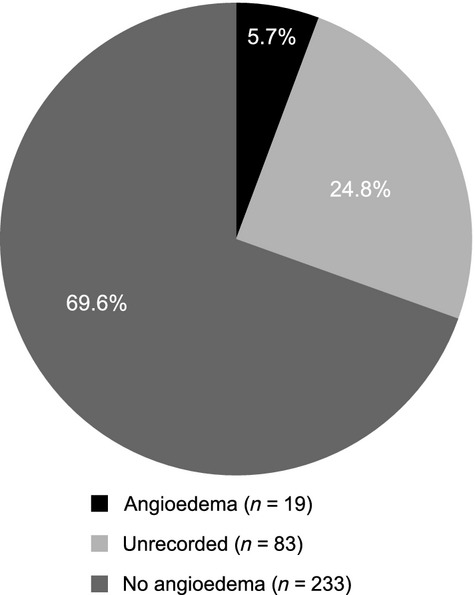

A total of 335 procedures were conducted in 144 patients who did not receive any prophylaxis at the time of surgery (Table 2). Fifty percent of procedures without prophylaxis for which the date was recorded occurred after 1984. Perioperative angioedema was recorded in 19/335 (5.7%) of procedures overall and was explicitly documented as not having been observed in 233/335 (69.6%). In the remaining 24.8% of procedures (83/335), the presence or absence of angioedema was not recorded (Fig. 2). Therefore, it can be estimated that the general risk of perioperative angioedema in patients with HAE-I or -II undergoing surgery ranges between 5.7% and 30.5% (CI: 3.5, 35.7%). Angioedema risk for procedures performed after 1984 was similar (range between 6.0% and 27.1%). The majority of procedures therefore did not result in angioedema.

Table 2.

Breakdown of procedures by patient age, sex, and HAE type

| Procedures | |

|---|---|

| No prophylaxis (final analysis) | 335 |

| HAE-I (%) | 309 (92%) |

| HAE-II (%) | 26 (8%) |

| Male (%) | 107 (32%) |

| Female (%) | 228 (68%) |

| Age <18 years (%) | 19 (6%) |

| Age ≥18 years (%) | 316 (94%) |

Figure 2.

Risk of angioedema during 335 procedures conducted in patients not receiving any prophylaxis for HAE prior to surgery.

The rates of angioedema across the various categories of surgical procedure are reported in Fig. 3. Categories representing significant numbers of procedures were abdominal (n = 113), ENT (n = 71), gynecological (n = 58), and orthopedic (n = 45) procedures. Examples of the range of procedures within each category are given in Table 3. Estimates for minimum and maximum risk of perioperative angioedema were 3.5–29.2% for abdominal (CI: 1.0, 38.5%), 4.2–32.4% for ENT (CI: 0.9, 44.6%), 6.9–32.8% for gynecological (CI: 1.9, 46.3%), and 11.1–31.1% for orthopedic procedures (CI: 3.7, 44.6%).

Figure 3.

Risk of angioedema in patients not receiving any prophylaxis prior to surgery by procedure.

Table 3.

Procedures without prior prophylaxis–distribution of most common surgical procedure sites by category

| Abdominal | n | ENT | n | Gynecological | n | Orthopedic | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appendectomy | 62 | Tonsillectomy (TE) | 35 | Cesarean section | 15 | Knee | 15 |

| Herniotomy | 19 | Adenotomy (AT) | 13 | Hysterectomy | 11 | Ankle | 5 |

| Cholecystectomy | 10 | Maxilla/sinus | 6 | Tubes/ovaries | 11 | Vertebra | 4 |

| Laparoscopy | 7 | TE+AT | 5 | Abrasion/abortion | 8 | Fractures | 4 |

| Miscellaneous | 15 | Miscellaneous | 12 | Miscellaneous | 13 | Miscellaneous | 17 |

| All sites | 113 | All sites | 71 | All sites | 58 | All sites | 45 |

A total of 19 procedures (5.7%) resulted in perioperative angioedema. These procedures included gynecological and abdominal surgery such as hysterectomy with and without ovariectomy (three cases), appendectomy (two cases), laparoscopy, laparotomy, tubal ligation, and an operation on ureterolithiasis (one case each). Edema also occurred in other types of operations such as knee surgery (three cases), adenectomy with and without tonsillectomy (two cases), hip surgery, orchidopexia, and reposition of nose fracture (one case each). However, minor procedures like suture of a thenar cut and injection of hyaluronic acid in the lips also caused postoperative angioedema (hand swelling and severe facial edema). A total of 7/19 patients with reported perioperative swelling underwent at least one further procedure without experiencing edema.

In most cases of perioperative angioedema, swelling was located at the site or region of surgery. However, one case of hand swelling after hysterectomy and another of foot edema after appendectomy were recorded. Three episodes of laryngeal edema were documented after laparoscopy (one case) and adenotomy with and without tonsillectomy (two cases). In two patients, perioperative angioedema was the first manifestation of HAE. One involved laryngeal edema following laparoscopy, requiring re-intubation.

Despite a lack of preprocedural or long-term prophylaxis, 233 procedures (69.6%) were completed without angioedema-related sequelae. These included a range of major procedures normally requiring prolonged operation and intubation or associated with a large degree of tissue damage. These included vertebral column operations (four procedures), kidney transplant, multiple organ surgery (hysterectomy, partial colon and bladder resection), cystectomy and prostatectomy, nephrectomy, resection of neuroblastoma, and operation on compartment syndrome (one of each procedure).

There was a trend toward a higher maximum risk of angioedema in HAE type II compared with HAE-I, with 15.4% minimum risk and 38.5% maximum potential risk in HAE-II (CI: 4.4, 59.4%) vs 4.9% minimum risk and 29.8% maximum potential risk in HAE-I (CI: 4.1, 35.2%).

Women with HAE-I and -II experienced more cases of perioperative angioedema compared with men: 4.8% (11/228) minimum risk, 36.0% (82/228) maximum potential risk in women (CI: 2.4, 42.6%) vs 7.5% (8/107) minimum risk and 18.7% (20/107) maximum potential risk in men (CI: 3.3, 27.4%).

Discussion

Aside from the surgical or diagnostic procedure itself, the risk of angioedema may be influenced by associated factors such as anesthesia, psychological stress, underlying disease, proximity to mucous membranes, position on the surgical table, and use of compression 25. For minor manipulations, such as mild dental procedures, current international HAE treatment guidelines recommend that no routine prophylaxis is required if C1-INH is immediately available 26. When performing more than mild manipulation, C1-INH prophylaxis should be considered 26. Where C1-INH is not available, short-term prophylaxis with attenuated androgens is recommended, even in children or during the last trimester of pregnancy (it is, however, recommended that this approach should be avoided in the first two trimesters). For intubation or major procedures, C1-INH should ideally be administered 1 h presurgery, or as close to, but no more than 6 h before commencement of the procedure. The recommended dose is 10–20 units per kg. A second dose of equal amount should be immediately available at the time of surgery, and doses should be repeated daily as needed until there is no further risk of angioedema 24.

The current study is the first to investigate the risk of angioedema in patients with HAE undergoing surgery and invasive procedures without the use of prophylactic treatment to prevent an HAE episode. To date, no attempt has been made to identify which patients are at greatest risk of an HAE episode or circumstances contributing to occurrence.

This study found that a small proportion of procedures without prophylaxis caused angioedema in HAE-I and -II compared with the rate expected based on perceived risk. The observed overall risk (5.7–30.5%) of angioedema in our retrospective analysis is comparable with that reported in the study by Bork et al., in which 21.5% of patients without prophylaxis experienced angioedema after tooth extraction and 12.5% of patients experienced angioedema with prophylaxis 21. There was no significant difference in risk between abdominal, ENT, gynecological and orthopedic procedures due to the broad confidence intervals.

The categorization of procedures by site used here was chosen for clinical reasons and does not necessarily indicate severity or extent of surgery but rather anatomical site. Within the category of abdominal surgery, appendectomy was the most frequent location, possibly related to a high percentage of unrecognized abdominal HAE episodes (Table 3). The extent of the surgical trauma involved did not seem to be a strong predictor of angioedema rates, with major procedures being among those less linked to angioedema. Apart from mechanical trauma, the psychological stress related to surgery or invasive procedures, as well as underlying diseases may have contributed to the manifestation of angioedema. Thyroid procedures, which like dental procedures might be anticipated to be associated with high rates of local (e.g laryngeal) angioedema, were not associated with perioperative angioedema in the nine cases examined here.

Our results show that perioperative angioedema may occur as the first clinical manifestation of HAE. The benefit of knowing patient HAE status prior to surgical procedures and the importance of having a readily available supply of acute treatment (such as C1-INH concentrate) in the emergency setting is clear. Individuals with HAE should share that information with family members, and members of families with a history of HAE should be encouraged to seek diagnosis and/or share that information with their physicians. Patients should, when possible, carry an emergency card with relevant treatment information.

Despite the relatively low risk of perioperative angioedema in patients with HAE-I and -II reported after different surgical procedures without prophylaxis identified in our study, our data highlight the unpredictable nature of acute HAE episodes and raise the need for routine consideration of preprocedural prophylaxis in patients with HAE.

The presence of perioperative angioedema after one procedure did not predict the outcome of further procedures regarding angioedema complications. This unpredictability makes it difficult to identify those patients at higher risk of an HAE episode in whom prophylaxis may be beneficial. This is particularly important considering the fact that angioedema can have severe consequences and a potentially life-threatening impact on the patient.

Potential weaknesses in this analysis include recall-bias, which may have led to either an over or underestimation of angioedema risk; another weakness is the lack of reliable information on the type of anesthesia used, particularly on intubation prior to surgery. Thus, conclusions cannot be drawn regarding the risk of angioedema associated with different types of anesthesia. Due to the broad range of risk estimated, it was not possible to distinguish differences in the risk of an HAE episode, for example, between subgroups of procedures or patients.

This study demonstrates that surgery or minor manipulations are situations that require special attention in patients with HAE. In this study, some patients with reported angioedema underwent further procedures without complication, while a wide range of major surgery did not lead to angioedema complications. However, angioedema was observed in some cases of minor procedures, and angioedema complications, when they did occur, were not necessarily confined to local edema. Furthermore, perioperative angioedema can be the first clinical manifestation of HAE.

The outcome of individual operations in patients with HAE-I or -II is unpredictable irrespective of type of surgery, HAE type, gender, or previous preprocedural angioedema complications. The varied recorded responses to surgical trauma reflect the variability of the disease itself. In elective surgery, C1-INH concentrate should be immediately at hand if available to minimize the patients’ risk. However, it is important to note that HAE should not form a barrier to patients seeking routine treatments, or lead to a delay in emergency procedures in the event that prophylaxis is not immediately at hand 26.

Our findings in this study, most notably the unpredictability of individual periprocedural HAE episodes, support current international treatment recommendations to consider short-term prophylaxis for patients with HAE on an individual basis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alexandra Thalhammer for her assistance in data collection and database curation and Heinz-Otto Keinecke, Accovion GmbH, Marburg, Germany, for statistical analysis. Medical writing assistance was provided by Neon Medical Ltd, UK, funded by CSL Behring.

Author contributions

Emel Aygören-Pürsün conceived and designed this investigation, analyzed and interpreted the data, and developed the manuscript. Inmaculada Martinez Saguer contributed to the acquisition of data. Inmaculada Martinez Saguer, Wolfhart Kreuz, Dirk Schwabe, and Thomas Klingebiel reviewed the manuscript critically and gave approval for the final version to be published.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors declares that they have a conflict of interest regarding the nature of the investigation.

References

- Agostoni A, Cicardi M. Replacement therapy in hereditary and acquired angioedema. Pharmacol Res. 1992;26(Suppl 2):148–149. doi: 10.1016/1043-6618(92)90639-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AE., III C1 inhibitor and hereditary angioneurotic edema. Annu Rev Immunol. 1988;6:595–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.06.040188.003115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicardi M, Johnson DT. Hereditary and acquired complement component 1 esterase inhibitor deficiency: a review for the hematologist. Acta Haematol. 2012;127:208–220. doi: 10.1159/000336590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gompels MM, Lock RJ, Abinun M, Bethune CA, Davies G, Grattan C, et al. C1 inhibitor deficiency: consensus document. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;139:379–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostoni A, Aygören-Pürsün E, Binkley KE, Blanch A, Bork K, Bouillet J, et al. Hereditary and acquired angioedema: problems and progress: proceedings of the third C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency workshop and beyond. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(Suppl 3):S51–S131. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AE, III, Bissler JJ, Aulak KS. Genetic defects in the C1 inhibitor gene. Complement Today. 1993;1:133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Davis AE., III The pathogenesis of hereditary angioedema. Transfus Apher Sci. 2003;29:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nzeako UC, Frigas E, Tremaine WJ. Hereditary angioedema: a broad review for clinicians. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2417–2429. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.20.2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen T, Cicardi M, Bork K, Zuraw B, Frank M, Ritchie B, et al. Hereditary angioedema: a current state-of-the-art review, VII: Canadian Hungarian 2007 International Consensus Algorithm for the Diagnosis, Therapy, and Management of Hereditary Angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100(1 Suppl 2):S30–S40. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)60584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork K, Hardt J, Schicketanz KH, Ressel N. Clinical studies of sudden upper airway obstruction in patients with hereditary angioedema due to C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1229–1235. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.10.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas H, Harmat G, Füst G, Varga L, Visy B. Clinical management of hereditary angio-oedema in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13:153–161. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3038.2002.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnewisser J, Rossi M, Späth P, Bürgi H. Type I hereditary angio-oedema. Variability of clinical presentation and course within two large kindreds. J Intern Med. 1997;241:39–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.76893000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas H, Szongoth M, Bély M, Varga L, Fekete B, Karádi I, et al. Angiooedema due to acquired deficiency of C1-esterase inhibitor associated with leucocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:298–300. doi: 10.1080/00015550152572985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visy B, Füst G, Bygum A, Bork K, Longhurst H, Bucher C, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection as a triggering factor of attacks in patients with hereditary angioedema. Helicobacter. 2007;12:251–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillet L, Longhurst H, Boccon-Gibod I, Bork K, Bucher C, Bygum A, et al. Disease expression in women with hereditary angioedema. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:484. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig TJ, Levy RJ, Wasserman RL, Bewtra AK, Hurewitz D, Obtulowicz K, et al. Efficacy of human C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate compared with placebo in acute hereditary angioedema attacks. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig TJ, Bewtra AK, Bahna SL, Hurewitz D, Schneider LC, Levy RJ, et al. C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate in 1085 Hereditary Angioedema attacks – final results of the I.M.P.A.C.T.2 study. Allergy. 2011;66:1604–1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuraw BL, Busse PJ, White M, Jacobs J, Lumry W, Baker J, et al. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor concentrate for treatment of hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:513–522. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuraw B, Cicardi M, Levy RJ, Nuijens JH, Relan A, Visscher S, et al. Recombinant human C1-inhibitor for the treatment of acute angioedema attacks in patients with hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:821–827. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicardi M, Banerji A, Bracho F, Malbrán A, Rosenkranz B, Riedl M, et al. Icatibant, a new bradykinin-receptor antagonist, in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:532–541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork K, Hardt J, Staubach-Renz P, Witzke G. Risk of laryngeal edema and facial swellings after tooth extraction in patients with hereditary angioedema with and without prophylaxis with C1 inhibitor concentrate: a retrospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumry W. 2011. Pre-procedural administration of nanofiltered C1 esterase inhibitor (Human) (CINRYZE®) for the prevention of hereditary angioedema (HAE) attacks after medical, dental, or surgical procedures. American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) Annual Meeting 19–22 March 2011, San Francisco, USA. Abstract 903.

- Grant JA, White MV, Li HH, Fitts D, Kalfus IN, Uknis ME, et al. Preprocedural administration of nanofiltered C1 esterase inhibitor to prevent hereditary angioedema attacks. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33:348–353. doi: 10.2500/aap.2012.33.3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen T, Cicardi M, Farkas H, Bork K, Longhurst HJ, Zuraw B, et al. 2010 International consensus algorithm for the diagnosis, therapy and management of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2010;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston DT. Diagnosis and management of hereditary angioedema. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2011;111:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst H, Cicardi M. Hereditary angio-oedema. Lancet. 2012;379:474–481. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60935-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]