Abstract

Background:

A lot of remedies, mostly plant based, were mentioned in the Persian old pharmacopoeias for promoting of burn and wound healing and tissue repairing. The efficacy of most of these old remedies is unexplored till now. Adiantum capillus-veneris from Adiantaceae family is one of them that was used to treating of some kinds of chronic wounds.

Methods:

Methanol extract was fractionated to four different partitions that is, hexane, ethyl acetate, n-butanol, and aqueous. The potential of A. capillus-veneris fractions in wound healing or prevention of chronic wounds were evaluated through angiogenesis and fibroblast proliferation, in addition to in vitro tests for protection against damage to fibroblasts by oxygen free radicals.

Results:

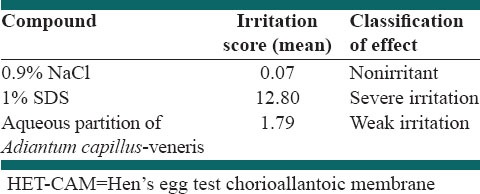

The aqueous part of A. capillus-veneris promoted significant angiogenesis (P < 0.05) through both capillary-like tubular formations and proliferation of endothelial cells in vitro. In addition, in the tests for protection against damage to fibroblasts by oxygen free radicals, aqueous and butanol fractions showed significant protective effects in the concentrations 50, and 500 μg/ml (P < 0.05) in comparison with a control group. In the toxicity testing, it showed weak irritation in the Hen's egg test chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) bioassay at the vascular level on the CAM of the chicken and no significant cytotoxicity in the MTT assays on normal human dermal fibroblasts.

Conclusions:

Angiogenic effects and protective effects against oxygen free radicals suggested aqueous partition of A. capillus-veneris local application for prevention of late-radiation-induced injuries after radiation therapy and healing of external wounds similar to bedsores and burns.

Keywords: Adiantum capillus-veneris, angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, hen's egg test chorioallantoic membrane test, Iranian traditional medicine, wound healing

INTRODUCTION

Many pharmacological studies are done on wound healing, but still there are many problems in clinics with prevention or treatment of open wounds like diabetic ulcers, bedsores and burns or tissue injuries after radiation therapy. Wound healing is a complex cascade of cellular and biochemical processes leading to the restoration of structural and functional of injured tissues. It involves several cellular and biochemical overlapping phases including hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and tissue remodeling.[1,2] In the hemostasis, platelet derived growth factors, Insulin like growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta activates angiogenesis, and also cause keratinocyte and fibroblast proliferation.[2] Although there is considerable interest in the application of angiogenic or fibroblast growth factors, a simpler alternative is interested. Medicinal plants are used for years in different countries for wound healing, and are preferred because of their low toxicity and their availability. Many remedies, mostly plant based, were mentioned in the Persian old pharmacopoeias of this system for promoting of burn and wound healing and tissue repairing. Distinguished Persian scientists such as Avicenna, Rhazes, Jorjani, and Aghili were familiar with these kinds of wound herbal treatments and spreading and classified them for treating of different kinds of wounds such as abrasion, punctured, cut, perforated, chronic, purulent, and septic wounds.[3,4] They were named those remedies under different old Farsi and Arabic terms like “Monbete Lahm” and “Ghorooh khabiseh”. These old terms has referred to some topical remedies that accelerate physiological sprouting of new vessels and tissues from preexisting tissues and modulate blood movements to the affected areas. The efficacy of most of these old remedies is unexplored until now. The aim of this study is to evaluate the potential of Adiantum capillus-veneris, as one of the plants used in Iranian traditional medicine,[3] for wound healing through standard in vitro assays on angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation assay, and in vitro assay for protection against damage by free reactive radicals to fibroblasts [Figure 1]. It is reported in Qrabadin-e Kabir, one of the pharmaceutical manuscripts in Persian medicine written by Aghili Khorasani, as topical application for treatment of open wounds.[3]

Figure 1.

A text about Adiantum application on wound healing from Qrabadin-e Kabir. “Qrabadin-e Kabir” is one of the pharmaceutical manuscripts in Persian medicine written by Aghili Khorasani in 1772 AD to introduce drugs, used in Iranian Traditional Medicine

METHODS

Plant material

Aerial parts of A. capillus-veneris L. (Adiantaceae) was collected in the summer time of 2012 from Semirom waterfall, Isfahan, Iran. Plant material was identified by Dr. Mustafa Ghanadian, and a voucher specimen (nos. 1661) deposited in the Herbarium of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

Preparation of plant extracts

The shade-dried aerial parts of the plant material (100 g) was macerated 3 days with methanol (600 cc × 3), at room temperature. Filtration and in vacuum evaporation of the solvent resulted in a green gum (8.3 g), which using liquid-liquid extraction, was partitioned through a separating funnel between n-hexane and methanol ethanol. The defatted methanol extract was evaporated and dissolved in H2O to make a suspension and then partitioned with different solvents such as ethyl acetate and n-butanol, respectively. Four different fractions, that is, hexane (A1, 2.3 g), ethyl acetate (A2, 0.8 g), n-butanol (A3, 6.4 g), and aqueous (A4, 0.5 g) parts were obtained which were evaporated to dryness under vacuum and stored in the refrigerator at −20°C.

Cell preparation

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and normal human dermal fibroblast line (AGO 1522) were obtained from a national cell bank of Pasteur, Tehran, Iran and were cultured according to the supplier's instructions. The HUVECs were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The AGO 1522 cell line was cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 + FBS 10% medium. All cells were used between passages 5-6.[5,6]

In vitro test for fibroblast MTT assay

The fibroblast growth stimulation and the cytotoxic effects of the samples were examined using the MTT assay method. Sixth passages of cells were trypsinized, suspended in RPMI + FBS 10%, and centrifuged. Supernatant was discarded and re-suspended in the same medium to give a suspension of 1.8 × 106 cells/ml. Fibroblast cells were seeded (4 × 103 cells/well) in a 96 well plate, RPMI + FBS 10% (170 μl) was added and incubated in 5% CO2 and 37°C for 24 h. About 20 μl of vehicle as a control or samples in different concentrations were added to impart a final concentration of 5, 50, 250, and 500 μg/ml. After 24 h incubation, the medium was discarded from the cells, replaced with 50 μl RPMI + 10 μl MTT, and incubated for 3 h. The medium was then removed, 50 μl dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) added, and the optical density of cells measured at 570 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader.[6]

In vitro test for protection against damage to fibroblasts by oxygen free radicals

The same culture of AGO 1522 (human dermal fibroblast) was used equally for the fibroblast growth stimulation assay. Sixth passages of cells were trypsinized, suspended in RPMI + FBS 10%, and centrifuged. Supernatant was discarded and re-suspended in the same medium to give a suspension of 4 × 106 cells/ml. About 10 μl of Fibroblast cells were seeded (4 × 103 cells/well) in a 96 well plate, RPMI + FBS 10% (150 μl) was added and incubated in 5% CO2 and 37°C for 24 h. 20 μl of H2O2 ( 0.1 mM) was added simultaneously with 20 μl of vehicle as a control or samples. Cells were treated with different concentrations of the test samples (5, 50, 250, and 500 μg/ml) and incubated for 24 h. Control and negative controls consisted of the cells treated with hydrogen peroxide alone, and the untreated cells and catalase (250 IU/ml), a scavenger of H2O2, as a standard antioxidant control.[6,7]

The medium was then pulled out from the cells, replaced with 50 μl RPMI + 10 μl MTT, and incubated for 3 h. The medium was then removed, 50 μl DMSO added, and the optical density of cells measured at 570 nm using an ELISA reader.[6]

In vitro test for human umbilical vein endothelial cells growth stimulation

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells suspension (10 μl) was seeded in each well (5 × 103 cells/well) and incubated in 5% CO2 and 37°C for 24 h. About 20 μl of samples or control in different concentrations (5, 50, 500, and 1000 μg/ml) were added. Doxorubicin wad used as positive control and wells without treatment as a control group. After 48 h treatment and incubation, the upper fluid of each well in the plate pulled out and then 10 μl of MTT + 50 μl RPMI were added. After 3 h, 50 μl DMSO was added to the wells and the optical density (OD) of the survival cell in each well were determined in a wavelength of 570 nm with ELAISA reader.[4] This procedure repeated for 3 times and the average of the cell survival percentage was determined as follows:

Cell survival % = [(OD experimental group – OD blank group)/(OD control group – OD blank group)] ×100.

Capillary-like tube formation assay

Cells were seeded in 24-well Matrigel-coated plates and were treated with samples as is described below. The capillary-like tubular formations were considered for evaluating angiogenic or antiangiogenic effects of the test sample of endothelial cells on Matrigel base (Invitrogen, USA) as described before [my article]. Matrigel thawed on ice was added 100 μl/well of a 24 well plate, carefully and incubated for 30 min in 37°C allowing matrigel to form a jelly base with a flat surface. About 40 μl of HUVECs suspension (105 cells/well) were seeded in each well. The wells were treated with 40 μl of test samples with the final concentrations of 5, 50, and 500 μg/ml per well at the same time. Blank or 10 ng/ml recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (R and D Systems, USA) alone served as a negative or positive control and culture medium added up to 300 μl. The plate was incubated for 24 h in 37°C and after incubation in vitro endothelial tube formation data were expressed as a percentage of the number of capillary-like tubes in treating wells to untreated control wells of triplicate readings.[4,8] Capillary-like tube formation was discovered with a Nikon inverted microscope and the images recorded digitally using Angioquant analysis software (Tampere University of Technology, Tampere, Finland).[9]

Hen's egg test

The hen's egg test chorioallantoic membrane (HET-CAM) bioassay is used to evaluate the potential irritation or toxicity induced by test samples at the vascular level of the CAM of the chicken. All examinations were carried out with fresh fertile Leghorn eggs which were obtained from a breeding farm (Jahade Keshavarzi, Isfahan, Iran) on the day of laying. Only eggs at a weight range between 50 g and 60 g were used. Eggs were kept for 24 h in a cold room (10°C). The eggs were divided into groups of 15 (test substances or control). Eggs placed in an incubator with a rotating tray and incubated at 38.3 ± 0.2°C and 58 ± 2% relative humidity. Eggs to be treated were candled on day 8 to throw away those that were spoiled. Eggs were removed from the incubator on day 9 for use in the assay. The section marked as the air cell was cut with a rotating dentist saw blade and then pare it off. The eggs had been removed from the incubator, prior to its use in the assay, and the inner membrane removed carefully with forceps, ensuring that the inner membrane is not injured. A 0.3 mL of 0.9% NaCl solution was directly applied on the CAM as a negative control to provide a baseline for the assay endpoints and to ensure that the assay conditions do not inappropriately result in an irritant response. 0.3 mL of 1% SDS, and 0.1 N NaOH were applied on the CAM as a positive control; a severe response in HET-CAM is expected. 0.3 mL of aqueous extract was applied directly onto the CAM surface. Effects are assessed in the near surroundings of the test item within 5 min. As demonstrated in Table 1, the time for the appearance of each of the endpoints (hemorrhage, vascular lysis, and coagulation) were monitored and recorded, in seconds.[10]

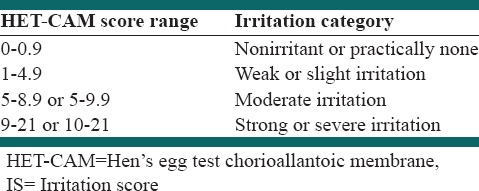

Table 1.

Irritation classification based on IS

Statistical analysis

The experiments are done in triplicates, and the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's posthoc comparison was used for multiple between-group comparisons. Analysis were performed with the statistical package SPSS version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

In vitro test for fibroblast MTT assay

Results are depicted in Figure 2 and show the viability, which is a reflection of cell counts. The effects did not show significant fibroblast proliferation (P < 0.05) or toxicity in aqueous or butanol fractions. Ethyl acetate and hexane fractions showed significant inhibitory effects on the growth of fibroblast cells at the higher concentration (500 μg/ml) by 64.07 ± 2.81 and 76.55 ± 7.2%, with IC50 values more than 500 μg/ml, suggesting that higher concentrations of these two factions are cytotoxic to fibroblast cells.

Figure 2.

In vitro test for fibroblast growth stimulation. AGO 1522 human dermal fibroblasts were plated in 96 well plate and after 24 h incubation treated with extracts and cell survival measured after 24 h incubation. *P < 0.05

In vitro test for protection against damage to fibroblasts by oxygen free radicals

Results for the fractions obtained from liquid–liquid partitioning are shown in Figure 3. It can be seen that the significant protective effect in comparisons with the control group treated with hydrogen peroxide alone, is shown by the aqueous fraction in the higher concentrations 50 and 500 μg/ml (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Protective effect of Adiantum fractions on human dermal fibroblasts against H2O2 (Perox)-induced oxidant injury. *P <0.05, **P<0.001

In vitro test for endothelial cell growth stimulation

The toxicity tests were done using HUVEC lines through standard MTT assay. Ethyl acetate and hexane fractions inhibit the growth of HUVECs by 35.4 ± 2.3, 76.4 ± 7.2% at 1000 μg/ml, respectively, with IC50 values of 851.7 ± 53.4 and >1000 μg/ml. None of the fractions showed significant toxicities (P < 0.05) at the concentrations 5, 50, and 500 μg/ml. The aqueous fraction at concentrations 500 and 1000 μg/ml showed significant stimulatory effects (P < 0.05) on proliferation of endothelial cells by 134 ± 7.5 and 138 ± 8.3% [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

In vitro test for endothelial cell growth stimulation. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were plated in 96 well plates and after 24 h incubation treated with extracts and cell survival measured after 24 h incubation. *P<0.05

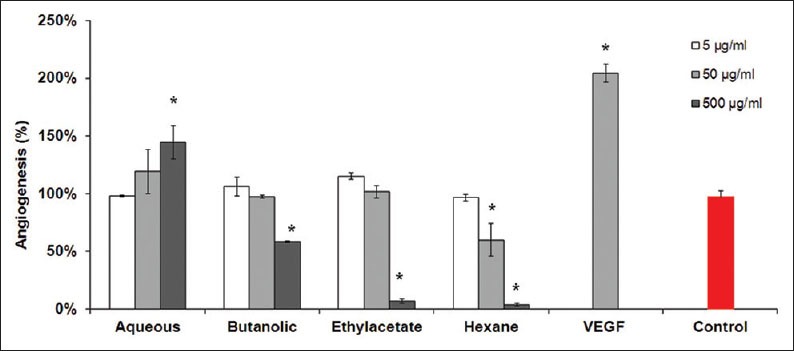

Capillary-like tube formation assay

Tube formation assay based on the ability of endothelial cells to form capillary-like tubular structures as seen in Figures 5 and 6, represents a quantitative model for studying inhibitors and activators of angiogenesis. Upon quantification of the capillary-tube-like structures using the angioquant software, aqueous fraction stimulates tube-similar structures at higher concentration of 500 μg/ml to 144.7 ± 14.4%. Butanol, ethyl acetate, and hexane fractions inhibited the size of tube-like structures at 500 μg/ml to 58.3 ± 3.3, 8.1 ± 0.6, and 4.3 ± 0.6%, significantly (P < 0.05). The IC50 values of the anti-angiogenetic effects of butanol, ethyl acetate, and hexane fractions were >500, 191.1 ± 7.5, and 85.3 ± 7.1 μg/ml, respectively.

Figure 5.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of capillary-like tube formation by Adiantum capillus-veneris fractions. The human umbilical vein endothelial cells were seeded in 24-well culture plates that precoated with Matrigel at a density of 105 cell/ml and treated with increasing concentrations of extracts for 24 h. Vascular endothelial growth factor (10 ng/ml) alone was used as a positive control. Endothelial tube formation was analyzed with Angioquant software and tube length was measured in the control group and concentrations. *P<0.05

Figure 6.

Effect of the aqueous fraction of Adiantum capillus-veneris on capillary-like tube formation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Tube formation of HUVECs on Matrigel in the presence of three concentrations of (5, 50, and 500 μg/ml), and untreated cell as control

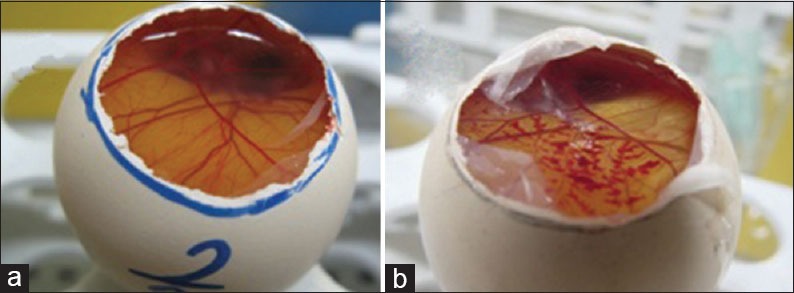

Hen's egg test

The HET-CAM bioassay was done to evaluate the potential irritation or toxicity induced by test samples at the vascular level of the CAM of the chicken [Figure 7]. In order to investigate the toxic effects of A. capillus-veneris aqueous fraction in the HET, the numerical time-dependent scores for lysis, hemorrhage, and coagulation were scored to give a single numerical value indicating the irritation potential of the test substance according to the criteria in Table 1, and mean irritation score was determined. The data are given in Table 2.

Figure 7.

(a) Normal, (b) chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) treated with an extract. The hen's egg test CAM bioassay is used to evaluate the potential irritation or toxicity induced by test samples at the vascular level of the CAM of the chicken

Table 2.

Irritation score, severity, and effect classification in the in vitro HET-CAM assay

DISCUSSION

Medicinal plants have been used for years in different countries as an alternative source of treatment for wound healing for wound healing and are chosen because of their low side effects and widespread availability.[10,11,12] In the present study, the potential of A. capillus-veneris in wound healing evaluated through angiogenesis and proliferation of endothelial cells in vitro. The aqueous partition of A. capillus-veneris promoted angiogenic effects through both capillary-like tubular formations and proliferation of endothelial cells in vitro. In addition, in the tests for protection against damage to fibroblasts by oxygen free radicals, aqueous and butanol fractions showed significant protective effects in comparison with a control group with no significant toxicitiy in the MTT assays on normal human dermal fibroblasts and with weak irritation in the HET-CAM bioassay at the vascular level on the CAM of the chicken.

Phytochemically, quercetin, and kampferol glycosides as kampferol-3-sulphate, kampferol-3-rhamnoglucoside, quercetine-3-glucuronyl, and rutin are the main flavonoids isolated from polar fractions of A. capillus-veneris[13,14,15] which could be in part responsible for the aqueous and butanol fractions. In a confirming report about quercetin effects on dermal wound healing in rats, there was an increase in the proliferation of cells in quercetin treated groups.[16] In addition to flavonoids, saponin glycosides with triterpenoid hydroxyhopanone structure may be also incorporated in the angiogenesis effects.[17] On this point are some evidences on saponins to be efficacious in wound healing. For instance, asiaticoside saponins from Centella asiatica and damaran type saponins from Panax ginseng root showed angiogenic properties.[18,19]

In addition to proangiogenetic properties, the protection effects of A. capillus-veneris against damage to fibroblasts by reactive radicals suggested it for prevention of chronic wounds similar to those happened after radiation therapy and for treatment of bedsores. In the treatments for cancer by radiotherapy, radiation-damaged tissues usually lead to chronic wounds.[20] It is reported that the progression of radiation-induced chronic wounds might be in part due to oxidative stress.[21] Therefore, applying an antioxidant-based drug could reduce or even treat late-radiation-induced injuries.[21] Reactive oxygen species such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radical are continuously produced after the initial injury, and thus may be responsible for chronic wound healing. Antioxidant activity of A. capillus-veneris may be due to the presence of polyphenolics and flavonoids especially quercetin and kampfreol derivatives present in the aqueous and butanol fractions.[22,23,24] Flavonoids are known for their antioxidant and cell protecting effects.[22,23] However, more investigations are suggested be done on aqueous fraction of A. capillus-veneris on cutaneous wound healing like cellular, and molecular action mechanisms via animal models.

CONCLUSIONS

Previously, multiple pharmacological properties like analgesic, antinociceptive, anti-implantation, and antimicrobial activities were reported from Adiantum genus.[17] Now, in the work outlined here wound healing properties are reported which might be explained in part by angiogenic properties of polar components present in the aqueous partition and to a lesser extent, to the antioxidant activities of the flavonoids present in both aqueous and butanol fractions. These activities suggested A. capillus-veneris local application for prevention of chronic wounds after radiation therapy and healing of external wounds similar to bedsores and burns.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper is part of the thesis of Abolfazl Fallah Yakhdani submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Pharm D. He is also grateful to the Dermatology Skin and Stem Cell Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran for their support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Dermatology Skin and Stem Cell Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Li J, Chen J, Kirsner R. Pathophysiology of acute wound healing. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum CL, Arpey CJ. Normal cutaneous wound healing: Clinical correlation with cellular and molecular events. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:674–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khorasani A, Shirazi MH. Tehran: Mahmoudi Bookstore Publication; 1999. Qrabadin-e Kabir; p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazemi M, Eshraghi A, Yegdane A, Ghannadi A. Clinical pharmacognosy – A new interesting era of pharmacy in the third millennium. Daru J Pharm Sci. 2012;20:1–2. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-20-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghanadian SM, Ayatollahi AM, Afsharypuor S, Javanmard SH, Dana N. New mirsinane-type diterpenes from Euphorbia microsciadia Boiss. with inhibitory effect on VEGF-induced angiogenesis. J Nat Med. 2013;67:327–32. doi: 10.1007/s11418-012-0686-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houghton PJ, Hylands PJ, Mensah AY, Hensel A, Deters AM. In vitro tests and ethnopharmacological investigations: Wound healing as an example. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100:100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phan TT, See P, Lee ST, Chan SY. Protective effects of curcumin against oxidative damage on skin cells in vitro: Its implication for wound healing. J Trauma. 2001;51:927–31. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200111000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnaoutova I, Kleinman HK. In vitro angiogenesis: Endothelial cell tube formation on gelled basement membrane extract. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:628–35. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niemistö A, Dunmire V, Yli-Harja O, Zhang W, Shmulevich I. Robust quantification of in vitro angiogenesis through image analysis. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2005;24:549–53. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2004.837339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kishore AS, Surekha PA, Sekhar PV, Srinivas A, Murthy PB. Hen egg chorioallantoic membrane bioassay: An in vitro alternative to Draize eye irritation test for pesticide screening. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27:449–53. doi: 10.1080/10915810802656996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chah KF, Eze CA, Emuelosi CE, Esimone CO. Antibacterial and wound healing properties of methanolic extracts of some Nigerian medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;104:164–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villegas LF, Fernández ID, Maldonado H, Torres R, Zavaleta A, Vaisberg AJ, et al. Evaluation of the wound-healing activity of selected traditional medicinal plants from Perú. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;55:193–200. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(96)01500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan Q, Wang J, Ruan J. Screening for bioactive compounds from Adiantum capillus-veneris L. J Chem Soc Pak. 2012;34:207–16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakane T, Maeda Y, Ebihara H, Arai Y, Masuda K, Takano A, et al. Fern constituents: Triterpenoids from Adiantum capillus-veneris. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2002;50:1273–5. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imperato F. Kaempferol 3-sulphate in the fern Adiantum capillus-veneris. Phytochemistry. 1982;21:2158–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomathi K, Gopinath D, Rafiuddin Ahmed M, Jayakumar R. Quercetin incorporated collagen matrices for dermal wound healing processes in rat. Biomaterials. 2003;24:2767–72. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan C, Chen YG, Ma XY, Jiang JH, He F, Zhang Y. Phytochemical constituents and pharmacological activities of plants from the genus Adiantum: A review. Trop J Pharm Res. 2011;10:681–92. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shukla A, Rasik AM, Jain GK, Shankar R, Kulshrestha DK, Dhawan BN. In vitro and in vivo wound healing activity of asiaticoside isolated from Centella asiatica. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;65:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura Y, Sumiyoshi M, Kawahira K, Sakanaka M. Effects of ginseng saponins isolated from Red Ginseng roots on burn wound healing in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:860–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robbins ME, Zhao W. Chronic oxidative stress and radiation-induced late normal tissue injury: A review. Int J Radiat Biol. 2004;80:251–9. doi: 10.1080/09553000410001692726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olascoaga A, Vilar-Compte D, Poitevin-Chacón A, Contreras-Ruiz J. Wound healing in radiated skin: Pathophysiology and treatment options. Int Wound J. 2008;5:246–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2008.00436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Askari G, Ghiasvand R, Feizi A, Ghanadian SM, Karimian J. The effect of quercetin supplementation on selected markers of inflammation and oxidative stress. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:637–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calderón-Montaño JM, Burgos-Morón E, Pérez-Guerrero C, López-Lázaro M. A review on the dietary flavonoid kaempferol. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2011;11:298–344. doi: 10.2174/138955711795305335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang MZ, Yan H, Wen Y, Li XM. In vitro and in vivo studies of antioxidant activities of flavonoids from Adiantum capillus-veneris L. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;5:2079–85. [Google Scholar]