Abstract

Background:

The probability and severity of effects of induced demand are because of the interaction between a range of factors that can affect physicians and patients behavior. It is also affected by the laws of the markets and organizational arrangements for medical services. This article studies major factors that affect the phenomenon of induced demand with the use of experts’ experiences of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Methods:

The research is applied a qualitative method. Semi-structured interview was used for data generation. Participants in this study were people who had been informed in this regard and had to be experienced and were known as experts. Purposive sampling was done for data saturation. Seventeen people were interviewed and criteria such as data “reliability of information” and stability were considered. The anonymity of the interviewees was preserved. The data are transcribed, categorized and then used the thematic analysis.

Results:

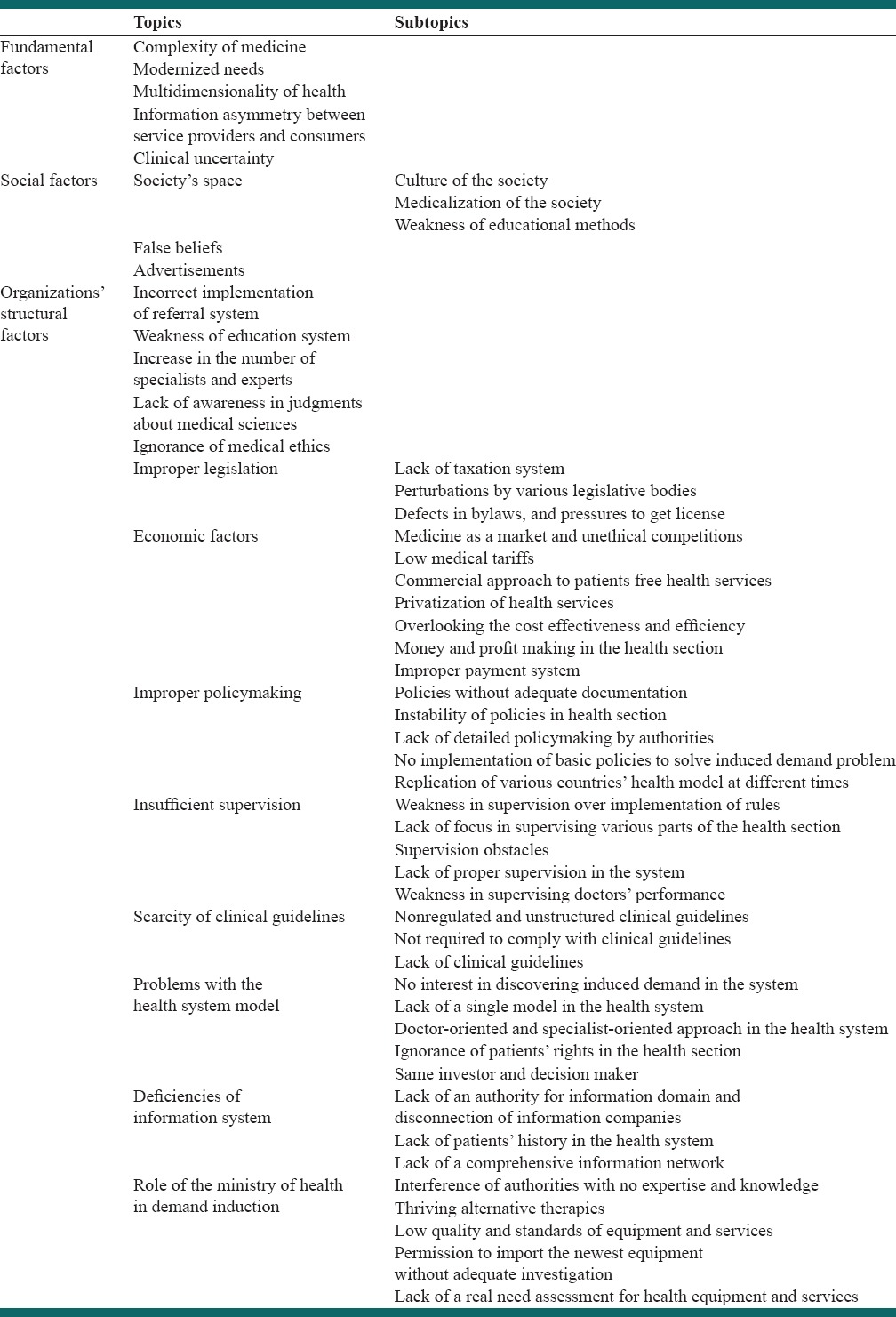

In this study, thematic analysis was conducted, and 77 sub-themes and 3 themes were extracted respectively. The three main themes include infrastructural factors, social factors, and organizational structural factors affecting induced demand. Each of these also has some sub-themes.

Conclusions:

Results of this research present a framework for analyzing the major causes of induced demand. The causes identified here include complexity of medicine, information mismatch between service providers and consumers, clinical uncertainty, false beliefs, advertisements, insufficient supervision, scarcity of clinical guidelines, weakness of education system, and ignorance of medical ethics. These findings help policymakers to investigate the induced demand phenomenon clear-sighted.

Keywords: Health system, induced demand, macro factors

INTRODUCTION

Costs of the health section have been dramatically increased in different nations in the last three decades.[1] To explain this rise, factors such as income, technology development, and age composition of the population are involved. Moreover, economists and policymakers emphasize on the inefficiency of supply and demand sections, which may induce demands in patients as a result of health service providers’ behavior.[2] The induced demand theory is a major area of research in health economics texts.[3,4]

Induced demand is a kind of demand requested with the help of a greater informational advantage for health care services, and excessive care is presented with dubious value.[5,6,7] The belief that medical care providers can generate demands for their services goes back to Roomer, who supposed that a hospital could fill its beds regardless of basic needs for hospital cares. Most of the studies agree that medical care providers are capable of influencing demands for their products.[8] In fact induced demand is to induce providing, caring, or selling unnecessary services to clients of health system that is accompanied by exercising power on behalf of service providers. Various economic and structural factors, behavior of service providers and receivers, and mismatch between their information are effective in demand induction,[9,10] which sometimes lead to using services or goods with little benefit.

It is surprising that despite problems and pieces of evidence, there is a strong belief in induced demand. Fuchs examined 46 pioneers of US health economics, including 24 economic theorists and 22 doctors. About two-thirds of health economists and doctors and three-quarters of economic theorists agreed on the induced demand phenomenon that doctors have the power to influence their patients to use services. The majority of respondents agreed that doctors induce demands.[11] These facts have directed economists to the question “what are the root causes of induced demand.”[12] Therefore factors influencing induced demand must be comprehensively analyzed to make instead the health system more efficient. This may play an important role in health system policymaking because of the variety of health cares. Little work has been done on induced demand in Iran; in a study entitled as “supplemental insurance and induced demand in chemical war victims” Mahbubi et al. investigated the role of supplemental insurance in induced demands. Their results show that for getting more profits from insurances, some doctors intentionally or unintentionally induce demands in patients who are not real.[13] In another study Abdoli and Varhrami compared induced demands among official and unofficial doctors and concluded that demand induction for pharmaceutical services is more frequent on behalf of general practitioners.[14] In Yuda's study, results indicated that medical suppliers increase inducement by 7.5% in response to 1% medical fee reduction.[15] Such studies have had a limited approach to induced demand while the present article tries to comprehensively investigate all causes affecting induced demand in health system.

In practice, the probability of induced demand and the intensity of its effects depend on the interaction of various factors that influences the behavior of doctors and patients and also affected by organizational arrangements and market regulations for medical services. Different factors including marketing, behavioral, structural, and regulatory are influential on this phenomenon that may act as motivational or preventive factors for doctors’ participation in and patients’ resistance to induced demand. In general, the domain of induced demand is more complex in medical services because of significant information mismatch and high costs of getting extra information for patients.[13] Hence, the goal of this article is to investigate influential factors in induced demand phenomenon with the use of expert's perceptions of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Iran) that will provide a specific framework for policymakers of the health section.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This qualitative research was performed in 2013 through deep interview. Participants were faculty members, doctors, hospital authorities, insurance managers, and researchers in the field of health economics with executive and management experience in the health system and familiar with induced demand. These people had several years of management experience in insurance companies, income and management section of hospitals, and vice president of health care supervision. The method of sampling was purposive. In other words, the interviewees were informed people with enough experience in this regard. Sample size fitted to the data saturation. Accordingly, 17 in-person interviews were conducted, recorded and written on article. The time of the interviews varied between 30 and 90 min.

Perform the study

For the validity of the research, the researcher conducted several interviews on a trial basis in advance, with the use of the advice, experience and assistance of the supervisors and the advisors. Then, for the data reliability, the veracity of the first interviews was considered by the supervisors and the advisors. When the revisions finished, the researcher began the work. For increasing the reliability, the data were extracted and referred to some participants and their viewpoint was considered. The criteria such as “data reliability, “assurance”, and “stability” were also considered. Morality was also considered through gaining the interviewees’ satisfaction. They were also informed that interviews are being recorded for the purpose of easy transcribing. Anonymity of the interviewees was preserved, and the participants were assured that the information is confidential.

Analysis

The method of the analysis of the data is based on thematic analysis. Data analysis stages included extraction of data, writing them on article, storing them in the computer, immersion in the data, coding, reflexive remarks, marginal remarks, memoing, and developing preposition. In the first stage after each interview, the text was transcribed, then, typed and stored on a computer immediately. In the next stage, the interview texts were examined and reviewed several times so that the researchers dominated the data. In the third stage, the data was categorized into semantic units (code) in the form of sentences and paragraphs related to the main meaning. Semantic units were also reviewed several times. Then an appropriate code was written down for each semantic unit. In a way that in each interview, sub-themes were separated, and then integrated, and reduced. Finally, the main themes were recognized. Reflective and marginal rein fact, ideas and viewpoints emerging in the researcher's mind was recorded during the interview and analysis. These signs related the notes to the other parts of the data.

RESULTS

About 77 sub-themes and 3 main themes were identified [Table 1]. These three main themes were fundamental, social, and structural factors influential on induced demand.

Table 1.

Macro factors of induced demand

Fundamental factors

There were five sub-themes identified for fundamental causes namely “complexity of medicine, modernized needs, multi-dimensionality of health, information asymmetry between service providers and consumers and clinical uncertainty.” Complexity of service proving in medicine; “e.g. if you want to pinpoint a subject, say why you performed angioplasty on this patient, he tells you many reasons why angioplasty was performed” (interview number 5). Modernized needs; “we are now going to doctors for things our parents would not go, when our parents did see a doctor for a nose-job?” (interview number 1). Multidimensionality of health; “well since health is generally a multidimensional phenomenon, it can be exploited and abused by many people!” (interview number 13). Information asymmetry between service providers and consumers; “because of problems in induced demand and health system services, the difference in awareness of service providers and receivers is proportionate to the need” (interview number 13). Clinical uncertainty in medicine; “medical science is very complicated, and you cannot comment easily that is how it is. Sometimes, it is possible to prescribe various drugs” (interview number 6).

Social factors

Participants mentioned social factors with three sub-themes of “society” space, false beliefs, and advertisements.” They suggested three sub-themes for the role of society's space in demand induction namely “culture of the society, medicalization of the society, and weakness of educational methods.” “This space known as medicalization space is a space in which everything is molded within the framework of health care services” (interview number 1). A participant said about “false beliefs:” “For example, some things are falsely believed in our society. Say a patient feeling dizziness, everyone says his cholesterol is high; while in 99% of situations this is not the case” (interview number 6). “Advertisement” is an important factor in the induction of unnecessary demands; participants said that “if you see an ad for a medical service, be sure that the financial and economical profits behind it for the one who advertises or for some hidden institutes are more important” (interview number 15).

Organizations’ structural factors

Some of the factors for induced demand were classified in the form of organization's structural causes. Participants named 13 sub-themes, including “improper legislation, incorrect implementation of referral systems, economic factors, improper policymaking, insufficient supervision, scarcity of clinical guidelines, weakness of education system, increase in the number of specialists and experts, lack of awareness in judgments about medical sciences, problems with the health system model, deficiencies of information system, role of the ministry of health in demand induction, and ignorance of medical ethics.”

The population-physician ratio approach is the commonest test used for the induced demand which includes the investigation of how to benefit from or change the price of medical services in response to a change in the number of the physicians of a certain region. The main hypothesis in the test is that in response to an increase in the physician-population ratio (reflective of greater competition among physicians) causes a downward pressure on their incomes. Physicians proceed to induce demands or increase their fees for keeping the income. A large number of the studies have investigated this hypothesis using comprehensive data; some of them have indicated some evidence regarding the support of the induction and some others have rejected the hypothesis.[6] In Stano's research, it is mentioned that the increase in the number of physicians and consequently increase in per capita of the health spending cannot be related to the induced demand because it may be that this effect is because of a possible increase in the availability and more extensive use of services.[16] In payment systems where physicians receive patients based on a list, a study done by Grytten and Sørensen indicated that if physicians encounter the lack of patients, they increase their consultations per patient to compensate the decrease in their own incomes.[17]

All in all, the available evidence regarding the increase in using medical services related to an increase in the number of physicians is not sufficient for indicating the induced demands. A large number of the other factors such as technological advances in healthcare and the increase in expectations in a part of the patients lead to an increase in the amount of use of these services. Therefore, only do the relationship between the increase in the supply of physicians and the increase in using survives not indicate a causal relationship. For example, the fact that societies respond to an increase in the number of physicians by increasing the amount of consuming healthcare services can easily improve the availability and accessibility of physicians.

Participants referred to three sub-themes for “improper legislation” which are “lack of the taxation system, perturbations by various legislative bodies, defects in bylaws, and pressures to get a license.” Lack of the taxation system; “our taxation system is influential in this issue, we don’t have such prohibiting leverages in our community and doctors are somehow free in their actions” (interview number 1). Perturbations by various legislative bodies; “the parliament exchanges tens of supplemental contracts, the ministry of justice does the court imposes sextuple penalty charges. You can see lots of perturbations in these issues!” (interview number 7). Defects in bylaws; participants mentioned outdated bylaws regarding scientific advances, pressure and power groups in issuing bylaws.

One participant considered “incorrect implementation of the referral system” as the cause of patients’ free access to specialized levels: “When we don’t have a referral system and everybody can easily access the specialized system, when we don’t have to wait list. It is not surprising that doctors go after induced demand” (interview number 1).

Participants mentioned eight sub-themes for “economic factors” in relation to Iran's health structure as follows: “Money and profit making in the health section, improper payment system, low medical tariffs, overlooking the cost effectiveness and efficiency, privatization of health services, free health services, commercial approach to patients, medicine as a market and unethical competitions.”

Money and profit making in the health section; “now the provider sees patients as money and wants to do something to divide or share them with others” (interview number 4). Improper payment system; “when a doctor is not paid sufficiently, this paves the way for other things” (interview number 4). Low medical tariffs; “because our medical tariffs are low, doctors go after such demands” (interview number 5). Overlooking the cost-effectiveness and efficiency; “most doctors demand magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or expensive tests. They use the simplest and the most expensive ways for the sake of their own profits” (interviews numbers 8 and 9). Privatization of health services; “these (doctors) help each other, invest their money, and buy an MRI device out of the hospital” (interview number 4). Free health services; “another factor is lack of control over insurance companies, for example, they say we provide some things free of charge, say you need not pay the fee-for visiting a doctor on this occasion, this on its own makes induced demand” (interview number 4). Commercial approach to patients; “you see, it is an issue of money. It is the personal profits at work here not patients’ health. It means that he or she has a commercial approach to this issue with personal benefits” (interview number 14). Medicine as a market and unethical competitions; “now regarding the created market and competitions, the health section is very profitable!” (interview number 7).

“Improper policymaking” is also one of the influential factors in demand induction with four subtopics of “policies without adequate documentation, lack of detailed policymaking by authorities, instability of policies in the health section and no implementation of basic policies to solve induced demand problem.” Policies without adequate documentation; “we want to blindly reduce the costs of cares, and this is no possible” (interview number 1). Lack of detailed policymaking by authorities; “because of these factors, we have not seen detailed policies or proper supervision on behalf of authorities that do exist!” (interview number 13). No implementation of basic policies to solve induced demand problem; “the fact is that every policy implemented up to has not been successful because it does not deal with problems fundamentally” (interview number 1).

Participants mentioned various factors regarding “supervision and its importance” classified as five sub-themes; these included “lack of proper supervision in the system, lack of focus in supervising various parts of the health section, weakness in supervising doctors’ performance, weakness in the supervision over the implementation of rules, and supervision obstacles.”

To explain “lack of proper supervision in the system,” participants referred to different aspects and therefore six new sub-themes were identified namely “no proper supervision over insurance companies, no supervision on behalf of the ministry of health-based on a common clinical guideline, lack of health-based supervision in the system, ineffectiveness of the supervision system on the quality and standards of service providing, and insufficient retrospective supervision.” “Insurance companies don’t supervise on behalf of their clients over service providers in terms of induced demand” (interview number 13). “Once the ministry of health began to set guidelines for some incurable disease, which were not successful, in fact that very institute (ministry) didn’t supervise its own guidelines” (interview number 12). “What I say is that this is not a health-based supervision” (interview number 14). “Besides, supervision in treatment and care should not be the case that you review it or perform a retrospection. It must be simultaneous” (interview number 7).

One of the participants referred to various supervisory organizations and disconnection of these organizations in terms of “lack of focus in supervising various parts of the health section” and stated that: “You see, insurance companies are independent, deputy of care section for itself for example! Licenses are supervised by medical council, medical council is supervised by deputy of care section. This is not the case that say you suppose a circle with every one attached to the center, it is reversed here!” (interview number 7).

Participants mentioned four sub-themes for “weakness in supervising doctors’ performance” including “insufficient supervision on behalf of the medical council, weak supervision over what doctors prescribe, insufficient supervision over doctors’ indications, and doctors supervising their own performance.” “If doctors get trained or supervised. For instance, what should be done by the medical council is now carried out by insurance companies themselves” (interviews numbers 8 and 9). “All of these are supervised but in line with what doctors do! However, the question of whether he or she needs this kind of drug or treatment! That's not what they do!” (interview number 14).

Participants stated six indications for “supervision obstacles” from different perspectives; these include “lack of supervisory tool, weak supervisory authorities, lack of a common treatment protocol/guideline among doctors, doctors’ ignorance of supervisory bylaws, lack of integrity among doctors’ performance and protocols of supervisory organizations, unspecialized supervisory organizations.” Lack of supervisory tools; “We are really unable to supervise because we don’t have the power and ability. We don’t have adequate tools” (interview number 7). Weak supervisory authorities; “it means that they exist legally but don’t exist regarding their authority and power or because of some scientific capabilities to mention some aspects for now” (interview number 2). Lack of common treatment protocols among doctors; “some prescribe antihistamine for a cold, some prescribe terfenadine. Different drugs are prescribed for that disease” (interview number 7). Doctors’ ignorance of supervisory bylaws; “for example in the case of a nose-job that is sometimes is performed in doctor's office. But the bylaws say that this is dangerous, and the operation must be done by a team. But our specialized doctors don’t take it seriously” (interview number 10). Lack of integrity among doctors’ performance and protocols of supervisory organizations; “when a patient complains to the courts or the medical council, they say why you didn’t provide their demands?” (interview number 12). Unspecialized supervisory organizations; “those supervisory organizations are not specialized! Patients complain to courts. Courts know nothing about specialized problems!” (interview number 12).

“Scarcity of clinical guidelines” had three sub-themes of “lack of clinical guidelines, nonregulated and unstructured clinical guidelines”; “because the clinical guidelines are not still regulated in Iran, there is no structure proposed for them” (interview number 12). A participant said: “They are not included in supervisory institutes or directional guidelines. They are not accountable to any official institute. They are not obliged to comply with a particular treatment guideline” (interview number 2).

One participant considered “weakness in education system” as the cause of improper training of doctors and believed that doctors use induced demand as a tool to get more information and experience: “When our education system is weak, doctors don’t get trained well, when they are not trained well, they will be low-literate, and must prescribe para-clinic tests. They perform trial and error as long as they understand patients’ problems” (interview number 4).

“Lack of awareness in judgments about medical science” may lead to incorrect judgment about doctors’ performance and, as a result, doctors induce unnecessary demands in patients to prevent future incorrect judgments. One of the participants stated that: “Judges don’t have correct medical knowledge; it is, of course, true that they have counselors. Issues are first dealt with in the medical council, but if referred to the courts, doctors are not defended properly. Because they know a little about medical issues” (interview number 6).

Participants mentioned five sub-themes in relation to “problems with the health system model,” which include “lack of a single model in the health system, doctor-oriented and specialist-oriented approach in the health system, no interest in discovering induced demand in the system, same investor and decision maker and ignorance of patients’ rights in the health section.” Lack of a single model in the health system; “in our system, they replicate a European model once, then 4 years later they copy a model from a different country. So there is no singe unified model” (interview number 7). Doctor-oriented and specialist-oriented approach in the health system; “most of the criticisms apply to the ministry because most of the specialists are there, they are doctor-oriented, specialist-oriented, they look from their own perspective” (interviews numbers 8 and 9). No interest in discovering induced demand in the health system; “no one is decided, and there is no initial motivation when that (induced demand) occurs, everyone sees it, but no one is aware here because in is latent” (interview number 13). Same investor and decision maker in the health section; “investors are those who make decisions! They set indicators themselves” (interview number 11). Ignorance of patients’ rights in the health section; “the fact is that if more attention is paid to patients in technical and specialized sections, they won’t be directed to such things! We are not kind with patients” (interview number 15).

There were some aspects for “deficiencies of information system” as far as participants were concerned; these were classified in three sub-themes including “lack of patients’ history in the health system, lack of authority for the information domain and disconnection of information companies and lack of a comprehensive information network.” Lack of patients’ history in the health system; “one of the causes of false demands is a lack of history and filings which must exist for patients” (interview number 15). Lack of authority for the information domain and disconnection of information companies; “here, one company writes the insurance program, one writes a program for water and electricity, one writes for education; these are not linked together at all, there are hundreds of them” (interview number 11). Lack of a comprehensive information network; one participant said about the lack of connection among health care centers across the country to exchange patients’ history: “There must be health bank established. Most of the actions are repeated here! A patient who gets sick in a city and refers to another city for treatment must spend money again and repeat the same tests!” (interviews numbers 8 and 9).

Five sub-themes were identified by participants in terms of “role of the ministry of health in demand induction; these included “thriving alternative therapies, permission to import the newest equipment without adequate investigation, lack of real need assessment for health equipment and services, interference of authorities with no expertise and knowledge, low quality and standards of equipment and services.” Thriving alternative therapies; “most of therapeutical methods such as traditional medicine, herbal medicine, energy therapy and so forth may have no therapeutical value but still have a good market as you can see” (interview number 7). Permission to import the newest equipment without adequate investigation; “they allow to import the newest equipment to the country. That's because importers make a profit, and also they themselves may be shareholders” (interview numbers 8 and 9). Lack of real need assessment for health equipment and services; “why do you issue licenses that in the future… who ever said that Isfahan needs an MRI so that peoples’ need turns to two then three MRIs!” (interview number 11). Interference of authorities with no expertise and knowledge; “those who interfere are high ranked officials, but they have no knowledge of this field! These are all influential” (interview number 12). Low quality and standards of equipment and services; “qualities and standards are low, when you have used a sonography a million times based on its assuming probe, why do you expect it to work fine?” (interview number 4).

One participant commented on “ignorance of medical ethics” as: “Unfortunately, there are cases such as pharmacies, medical diagnostic laboratories, or diagnostic imaging centers where a doctor says explicitly that: how much do I get if I send you patients?” (interview number 15).

DISCUSSION

Induced demand is a result of various economic and structural factors and the health market.[4,14,18,19] This research classified the effective factors in induced demand in three major topics. These topics are fundamental causes, social causes, and structural causes which affect induced demand. Regarding the ideas of the participants of the study, information asymmetry, advertisement, ignoring medical ethics, economic factors, and poor supervision are the most important reasons of occurring the induced demands in the healthcare system in such a way that economic factors were mentioned in 15 interviews, information asymmetry in 12, ignoring medical ethics and advertisement in 8, and poor supervision in 10 interviews.

It must be kept in mind that results of qualitative studies are usually stated case by case and are valid in respect to the participants. The present research was performed in the Medical University and insurance companies of Isfahan, Iran with available doctors and because of the varying nature of different majors and fields, result cannot be generated to other universities and fields of studies.

Regarding experts’ ideas in this study, one of the fundamental causes was information asymmetry. Many studies state that doctors’ powerful markets is based on information asymmetry and induced demand is significantly dependent on the fact that doctors exploit the mismatch for their own profits.[5,11,14,18,19,20] Izumida, Broomberg and Price, Hansen et al., and Arrow claim that a doctor can induce in a patient that he or she needs more intensive treatment, because a doctor has more information than the patient.[21,22,23,24,25] Another fundamental cause is complexity of medicine. Richardson and Peacock state that medical decision making is often complicated and uncertain, and even if all medical norms are met, there still remain some dark points.[26] Fabbri and Bickerdyke believe that the the most complicated a service is, the higher the probability of induced demand.[4,27]

Experts considered clinical uncertainty as one of the fundamental causes in the study. Wennberg et al. show that clinical uncertainty and induced demand exist especially for voluntary services such as tonsillectomy, hysterectomy, and colonoscopy.[28] Bickerdyke and Wennberg state that the effect of clinical uncertainty in the process of decision making by doctors can be a factor of induced demand.[4,29] According to the experts of the present study, another fundamental reason is the modernization of needs. Nowadays health needs have changed in terms of disease patterns; patients’ living conditions and technological advancements and the phenomenon of modernized needs is introduced to the world that may pave the way for providing unnecessary services. Fabbri and Monfardini, Lien et al., and Gruber and Owings regard epidemiologic changes, evolution of needs, demographic changes and variety of preferences as factors influencing induced demand.[30,31,32] Among the obtained fundamental reasons, most of the experts emphasized the information asymmetry between patients and physicians.

Regarding the administered interviews in this study, the social reasons have significant roles in the induced demand. The medicalization of our society's cultural environment has made everything take a medical framework. Bickerdyke states that induced demand is affected by environmental influences such as cultural background and society's attitude.[4] Advertisements are important causes of inducing unnecessary demands that can gradually direct patients with little information toward false services.

The experts of this study emphasized the economic factors heavily, and according to them, these factors have significant roles in the induced demand. They took the inappropriate payment system and medical fees as the factors effective on the induced demand. When a doctor does not feel financial satisfaction, he or she is more tempted to induce unnecessary services. Various studies have shown that there is a relationship between proper use of treatments and refunds.[31,33,34,35] Broomberg and Price, and Madden et al. state that different methods of payment to providers influence significantly their professional behavior and the extent to which they seek their own interests.[22,36] Evidence shows that with the introduction of fee-for-service system, the tendency to use more increases and providers make more profit with repeating diagnostic tests and prescribing more expensive tests.[22,37,38,39] Anderson and Glesnes-Anderson and Iversen conclude that in a system where doctors have a particular list of patients, they use a short list to increase demands and therefore can offer more services for each patient.[20,40] Amporfu states that salaried doctors have no motivation of inducing demand.[41] Giuffrida and Gravelle and Grossman mention that fee changes lead to demand induction on behalf of general practitioners.[22,42]

Regarding the results obtained from the study, the low medical tariffs are effective on the induced demand as well. Doctors feel the need to compensate low tariffs with unnecessary services for patients. Free health services and the failure to pay franchise are among the reasons obtained in the study. They make patients refer for unnecessary services. Borhanzade states that low base price of services in the health market in comparison with other economic markets has led to multi-priced services; this itself is a cause for induced demand.[43] According to Mahbubi et al. free services make some people try to use them as much as possible and induce some demands intentionally or unintentionally.[13] Dosoretz shows in his study that when treatment standards seem to be vague, induction's effects increase and doctors get tempted to direct their patients toward the most expensive treatments.[44]

According to the experts of this study, a commercial approach in healthcare is another reason for the occurrence of the induced demand. It looks at patients as goods and damages the health-based view. It can be said that there is a phenomenon known as the medical market. It has created an unethical competition among service providers who seek their own interests, and patients’ real interests are overlooked.[45]

Regarding the ideas of the experts of the present study, the lack of accurate supervision in the system causes the induced demand to occur easily. Insurance companies do not properly supervise and control health service providers. They usually pay attention to what doctors prescribe and do not check the validity of their prescription. Besides, the ministry of health and care do not use common clinical guidelines. The experts of the present study emphasized that the lack of clinical guidelines in Iran's healthcare system causes the induced demand because there is no tool for supervising the performance of healthcare providers. Borhanzade claims that when insurance companies do not control and supervise their own payment system and do not investigate service sellers according to service providing standards, patients demand extra services with more ease.[43]

According to the experts of this study, one of the important issues is the insufficient supervision of physicians’ performance. Supervision over doctors’ performance is an important issue because they are at the frontiers of dealing with patients. Weakness in this area can double unnecessary demands since doctors’ syndicates are not properly investigated, and even if they were, it is after the prescription when patients have received wrong services. In the health system, doctors act both as supervisors and decision makers where in some cases it is possible that their profits are preferred over patients’ interests. Bickerdyke states in his study that the kind of systems implemented to survey and investigates doctors’ activities and systems which supervise doctors’ relations with other providers of health care services affect demand induction.[4]

The experts proposed that the supervisory barriers are another factor in the phenomenon of the induced demand. They mentioned that shortage of facilities and extensive works in insurance companies are crystal clear. Weak legislation and scientific abilities also lead to induced demand. One of the obstacles is a lack of a common treatment protocol among doctors that complicate supervision. Clinical guidelines are not common in Iran's health system. No proper law and structure exist for providing clinical guidelines in the health system. Moreover because of lack of necessary infrastructures, doctors are not required to observe clinical guidelines. Broomberg and Price state that doctor's act independently and there is no organized mechanism to develop treatment protocols, surveying systems of clinical activities, or service use profiles. This leads to irrational and contradictory use of health care resources.[22] Dosoretz states that when clinical values are not defined, as economic actors, doctors and other providers maximize their interests.[44]

The experts declared that the educational system has an undeniable role in creating the induced demand. Borhanzadeh mentions the education model as a cause of unnecessary medical services and states that because of inefficiency of education models, graduates do not have sufficient capabilities and skills in diagnosing diseases and problems of patients.[43] Izumida and Bickerdyke emphasize the inefficiency of education models in the health system.[4,25] One structural cause of induced demand is the increase of specialists and experts; this makes the balance between supply and demand instable and to survive in this competitive market these work forces try to attract patients even through providing unnecessary services. Lien et al., Cromwell and Mitchell, and Rice and Yip mention the number of competitors as a variable affecting induced demand.[32,46,47,48]

According to the experts of the present study, the lack of knowledge of the judgment levels of medical sciences results in poor judgment regarding physicians’ performance and, as a result, doctors induce unnecessary demands in patients to prevent future incorrect judgments. Lack of a single model in the health system may also cause demand induction because it does not provide a situation where induced demand is opposed. Moreover, a doctor-orientated health system pays more attention to doctors’ profits than patients.’ Considering the present conditions it can be said that there is no interest in discovering induced demand in the system, and maybe no one considers it as a major problem.

The experts mentioned in their interviews that the Ministry of Health and Medical Education has a significant role in the induced demand and can act as an agent or controller of this phenomenon. When new methods are implemented regardless of the costs of their effectiveness and efficiency, the induced burden imposes demands on the system. Bickerdyke states that the probability of providers’ induced demand depends on the structural framework of health care organizations and on providing medical services. A combination of organizational factors influences the extent of induced demand.[4] Medical ethics is also an important and fundamental factor, ignorance of which increases induced demand. Broomberg and Price state that professional and ethical considerations in which providers operate can affect greatly their behavior.[22,49]

CONCLUSIONS

Results of this research present a framework for analyzing the major causes of induced demand; the most significant causes were fundamental, social, and structural causes. Findings help policymakers of the health section to investigate the induced demand phenomenon clear-sightedly. More research in this area can examine the roles of organizational levels of the ministry of health and society in demand induction. The suggestion is that to instead control induced demand, public awareness and knowledge should be improved, and financial motivations of health service providers should be controlled by proper policies, and clinical guidelines should be used as a powerful tool for supervising doctors’ performance.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Besley T, Gouveia M. Alternative systems of health care provision. Econ Policy. 1994;19:199–258. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delattre E, Dormont B. Fixed fees and physician-induced demand: A panel data study on French physicians. Health Econ. 2003;12:741–54. doi: 10.1002/hec.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavoosi Z, Rashidian A, Poormalek F. Measurement of family interfaces with high prices of health: Longitudinal study in 17th region of Tehran. Hakim J. 2009;12:38–47. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bickerdyke L, Dolamore R, Monday L, Preston R. Canberra: Productivity Commission; 2002. Supplier-Induced Demand for Medical Services. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdoli G. Induce demand theory of the information asymmetry between patients and doctors. Econ Res J. 2005;68:91–114. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman R, Sloan F. Competition among physicians. In: Greenberg W, editor. Competition in the Health Care Sector: Ten Years Later. London: Duke University Press; 1988. pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pauly MV. Chicago: University Chicago Press; 1980. Doctors and Their Workshops: Economic Model of Physician Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keyvanara M, Karimi S, Khorasani E, Jazi MJ. Experts’ perceptions of the concept of induced demand in healthcare: A qualitative study in Isfahan, Iran. J Educ Health Promot. 2014;3:27. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.131890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell JM, Scott E. New evidence of the prevalence and scope of physician joint ventures. JAMA. 1992;268:80–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeder SA. Physician supply and the U.S. Medical marketplace. Health Aff (Millwood) 1992;11:235–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.11.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grytten J, Sørensen R. Type of contract and supplier-induced demand for primary physicians in Norway. J Health Econ. 2001;20:379–93. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(00)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crane TS. The problem of physician self-referral under the Medicare and Medicaid antikickback statute. The Hanlester Network case and the safe harbor regulation. JAMA. 1992;268:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahbubi M, Ojaghi S, Ghiyasi M, Afkar A. Supplemental insurance and induce demand in veterans. Med Veterans J. 2010;2:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdoli G, Varhami V. The role of asymmetric information in induce demand: A case study in medical services. Health Manage. 2010;13:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuda M. Medical fee reforms, changes in medical supply densities, and supplier-induced demand: Empirical evidence from Japan. Hitotsubashi J Econ. 2013;54:79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stano M. An analysis of the evidence on competition in the physician services markets. J Health Econ. 1985;4:197–211. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(85)90029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grytten J, Sørensen R. Busy physicians. J Health Econ. 2008;27:510–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cline RR, Mott DA. Exploring the demand for a voluntary Medicare prescription drug benefit. AAPS PharmSci. 2003;5:E19. doi: 10.1208/ps050219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palesh M, Tishelman C, Fredrikson S, Jamshidi H, Tomson G, Emami A. "We noticed that suddenly the country has become full of MRI".Policy makers’ views on diffusion and use of health technologies in Iran. Health Res Policy Syst. 2010;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson G, Glesnes-Anderson V. Rockville, MD: Aspen Publication; 1987. Health Care Ethics. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arrow JK. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. Am Econ Rev. 1963;53:941–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broomberg J, Price MR. The impact of the fee-for-service reimbursement system on the utilisation of health services. Part I. A review of the determinants of doctors’ practice patterns. S Afr Med J. 1990;78:130–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossman M. The human capital model. In: Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP, editors. Handbook of Health Economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen BB, Sørensen TH, Bech M. Variation in Utilization of Health Care Services in General Practice in Denmark. University of Southern Denmark, Institute of Public Health – Health Economics. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izumida N, Urushi H, Nakanishl S. An Empirical Study of the Physician-Induced Demand Hypothesis: The Cost Function Approach to Medical Expenditure of the Elderly in Japan. Rev Popul Soc Policy. 1999;8:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson JR, Peacock SJ. Supplier-induced demand: Reconsidering the theories and new Australian evidence. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2006;5:87–98. doi: 10.2165/00148365-200605020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fabbri D. Supplier induced demand and competitive constraints in a fixed-price environment. Dipartimento di Scienze Economiche, Università; di Bologna. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wennberg JE, Barnes BA, Zubkoff M. Professional uncertainty and the problem of supplier-induced demand. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:811–24. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wennberg JE. On patient need, equity, supplier-induced demand, and the need to assess the outcome of common medical practices. Med Care. 1985;23:512–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fabbri D, Monfardini C. Dept. of Economics, University of Bologna; 2001. Demand induction with a discrete distribution of patients. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruber J, Owings M. Physician financial incentives and cesarean section delivery. Rand J Econ. 1996;27:99–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lien HM, Albert Ma CT, McGuire TG. Provider-client interactions and quantity of health care use. J Health Econ. 2004;23:1261–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hemani ML, Makarov DV, Huang WC, Taneja SS. The effect of changes in Medicare reimbursement on the practice of office and hospital-based endoscopic surgery for bladder cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:1264–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Labelle R, Stoddart G, Rice T. A re-examination of the meaning and importance of supplier-induced demand. J Health Econ. 1994;13:347–68. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sada MJ, French WJ, Carlisle DM, Chandra NC, Gore JM, Rogers WJ. Influence of payor on use of invasive cardiac procedures and patient outcome after myocardial infarction in the United States. Participants in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1474–80. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Madden D, Nolan A, Nolan B. GP reimbursement and visiting behaviour in Ireland. Health Econ. 2005;14:1047–60. doi: 10.1002/hec.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bardey D, Lesur R. Optimal Regulation of Health System with Induced Demand and Ex post Moral Hazard. Ann Écon Stat. 2006;25:279–93. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasaart F. Incentives in the Diagnosis Treatment Combination payment system for specialist medical care Datawyse. Universitaire Pers Maastricht. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lubeck DP, Brown BW, Holman HR. Chronic disease and health system performance. Care of osteoarthritis across three health services. Med Care. 1985;23:266–77. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198503000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iversen T. The effects of a patient shortage on general practitioners’ future income and list of patients. J Health Econ. 2004;23:673–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amporfu E. Private hospital accreditation and inducement of care under the ghanaian national insurance scheme. Health Econ Rev. 2011;1:13. doi: 10.1186/2191-1991-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giuffrida A, Gravelle H. Inducing or restraining demand: The market for night visits in primary care. J Health Econ. 2001;20:755–79. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borhanzade A. Induced Demand and the Cost of Tests and its Impact on Cost and Family Health. Iranian Association of Clinical Laboratory Doctors. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dosoretz AM. Rerforming Medicare IMRT (Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy) Reimbursement Rates: A Study Investigating Increasing IMRT Utilization Rates and Doctors’ Incentives TUFTS University. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferguson BS. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Atlantic Institute for Market Studie; 2002. Isseus in the Demand for Medical Care: Can Consumers and Doctors be Trusted to Make the Right Choices? [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cromwell J, Mitchell JB. Physician-induced demand for surgery. J Health Econ. 1986;5:293–313. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(86)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rice TH. The impact of changing medicare reimbursement rates on physician-induced demand. Med Care. 1983;21:803–15. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yip WC. Physician response to Medicare fee reductions: Changes in the volume of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgeries in the Medicare and private sectors. J Health Econ. 1998;17:675–99. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rice TH, Labelle RJ. Do physicians induce demand for medical services? J Health Polit Policy Law. 1989;14:587–600. doi: 10.1215/03616878-14-3-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]