Abstract

Background:

This study explored the strategies to overcome diabetes-related social stigma in Iran.

Materials and Methods:

This paper is part of an action research study which was designed in Iran in 2012 to plan and implement a program for overcoming diabetes-related stigma. Participants were people with type 1 diabetes, their family members, people without diabetes, and care providers in a diabetes center. Data collection was done through unstructured in-depth interviews, focus groups, e-mail, Short Message Service (SMS), and telephone interview. Data were analyzed using inductive content analysis approach.

Results:

Participants believed that it is impossible to overcome the stigma without community-based strategies. Community-based strategies include education, advocacy, contact, and protest.

Conclusions:

The anti-stigma strategies obtained in the study are based on the cultural context in Iran. They are extracted from statements of a wide range of people (with and without diabetes). However, during planning for stigma reduction, it is necessary to note that the effectiveness of social strategies varies in different studies and in different stigmatizing conditions and many factors are involved. These strategies should be implemented simultaneously at different levels to produce structural and social changes. It should be accepted that research on reducing health-related stigma has shown that it is very difficult to change beliefs and behavior. Evidence suggests that individuals and their families should be involved in all aspects of the program, and plans should be made according to the local conditions.

Keywords: Anti-stigma strategies, diabetes-related stigma, Iran, qualitative research, stigma management

INTRODUCTION

Negative social appraisal or diabetes-related social stigma is a major and potential consequence of living with diabetes.[1] It is an important phenomenon in many countries, especially Asian countries[2,3] such as China,[4] India,[5] and Iran.[6,7,8,9] Stigma is a trait or characteristic that disqualifies people for full social acceptance.[10] Health-related stigma is based on an enduring feature of identity conferred by a health problem or a health-related condition.[11] Health-related stigma is a complex issue including both social and psychological aspects.[2] Stigma is a social context-dependent phenomenon that occurs in relationships.[12]

Diabetes-related stigma is particularly severe since diabetes is a chronic and life-threatening condition.[2] It has various negative effects and outcomes. Important life areas such as people's dignity, social status, employment opportunities or job security, marriage, family relationships, and friendships are commonly affected by stigma.[9] Therefore, it is necessary to assess the stigmatizing effect of diabetes[13] and to eliminate it for health promotion. In recent years, several experts and organizations[2,14,15] have also emphasized on the necessity of efforts to reduce diabetes-related stigma. In fact, if we can reduce diabetes-related stigma, it would be possible to mitigate or prevent its negative consequences.[16] Thus, recently, taking efforts to overcome stigma and discrimination against people with diabetes has been proposed as a goal of the International Diabetes Federation (IDF).[15] The healthcare systems are expected to try to overcome diabetes-related stigma.

Despite numerous calls for stigma reduction, so far, no study has been conducted to explore the useful strategies to overcome diabetes-related stigma in Iran. Literature reports have mentioned several approaches for other stigmatizing conditions, but these approaches are not specifically related to reduction of stigma on diabetes. On the other hand, it is impossible to develop generic stigma reduction strategies for all health conditions, given the specificity of these conditions and the complexity of the factors related to each person's experience of stigma.[17] It is necessary to develop culturally sensitive strategies. This study explored the ways to overcome diabetes-related stigma at the community level in Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This paper is the first part of the findings of an action research study which was designed in Iran in 2012 to plan and implement a program for overcoming diabetes-related stigma. Action research is a way for engaging people to share their experiences and to learn through collective reflection and analysis. Action research studies consider local cultural beliefs and are an appropriate approach to address stigma. Kemmis and McTaggart's method guides the action research, which includes four phases: planning, action, observation, and reflection. Qualitative content analysis was used to derive strategies to overcome the diabetes-related stigma in the planning phase.

The study participants (in the planning stage) consisted of volunteered medical and nursing personnel working in a selected diabetes center, people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), and people without diabetes living in Isfahan, Iran. The researchers contacted all people with type 1 diabetes referring to the selected diabetes center in Isfahan. In addition, some people with diabetes introduced their family members who volunteered to participate in the study. Also, the researchers chose volunteers without diabetes from public places. All candidates were selected purposefully and invited to participate in this action research.

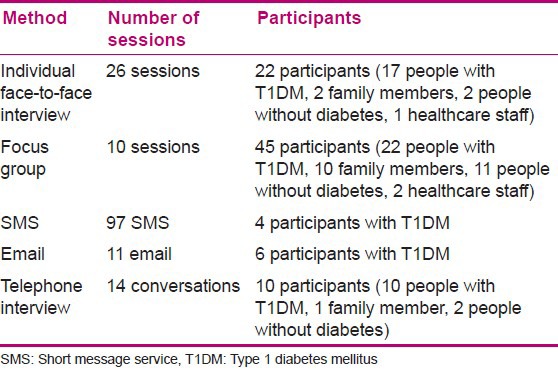

Data collection was done through unstructured in-depth interviews, focus groups, e-mail, Short Message Service (SMS), and telephone interview to extract strategies to overcome the diabetes-related stigma [Table 1].

Table 1.

Details of the data collection methods

Individual interviews formed the main data collection method. Participants were asked to reflect on the stigmatizing attitude and behaviors, and to respond to an open question, “How can we reduce diabetes-related stigma in the community?” Detailed questions were asked subsequently based on participants’ initial responses to encourage them to fully describe each mentioned strategy. Each interview lasted between 40 and 90 min based on participants’ preference.

The focus groups were used to complete the obtained information. The main researcher acted as a facilitator. She mentioned the research goal. She emphasized that the purpose of the meeting is not to reach consensus on strategies and the goal of the study is to have all possible strategies based on participants’ experiences and opinions. Focus groups lasted 90-165 min based on participants’ preference. Focus group meetings for people with T1DM, people without diabetes, family members, and staff were held separately. Finally, all participants were told if they remembered a different approach, they could give it via e-mail or SMS.

All interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Vague statements were checked through telephone interview or re-interview. The participants’ identification information was removed from the transcripts. Data collection continued until data saturation. Due to the qualitative nature of the data in this phase of the action research, data were analyzed using conventional content analysis approach.

Analysis was conducted concurrently with data collection. This approach involves three steps including open coding, creating categories, and abstraction.[18] For this purpose, after repeated listening, and reading the transcribed files, the text was reviewed for open coding. Notes and headings were written in the margins while reading it. It was repeated several times, and as many headings as necessary were written down to describe all the mentioned strategies. After that, all the strategies were written on the coding sheets. Then, the strategies were grouped. One heading encompassing all strategies was considered for each category. Finally, all the similar groups and classes were placed in larger classes, so that four categories were formed. Research team members were responsible for data analysis. They read and coded each transcript separately.

Researchers used prolonged engagement for data collection and data analysis. Moreover, peer debriefing (all authors discussed the data analysis process) and member checks (all the extracted concepts were returned to the participants and examined) were followed for enhancing credibility. Inquiry audit by an independent qualitative researcher was used for enhancing dependability and confirmability. Researchers tried to select different participants for enhancing transferability.

The ethical committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved the project of inquiry. Researchers selected the participants who volunteered to participate after introducing themselves and informing them about the research objectives. Then, they obtained verbal consent for voice recording. Participants were assured that all stories would be confidential and they were free to quit at any time they wished.

RESULTS

Seventy-four people participated in extracting the anti-stigma strategies.. The participants consisted of 44 people with T1DM (25 women, 19 men; age 19-50 years; a history of diabetes of about 2-35 years; high school education up to PhD), 12 family members (2 men, 10 women; high school education up to bachelor's degree), 15 non-diabetic patients (9 women, 6 men; age 18-55 years; with elementary education up to graduation), and 3 healthcare personnel in the selected endocrine center (3 women with BSc to MSc degree).

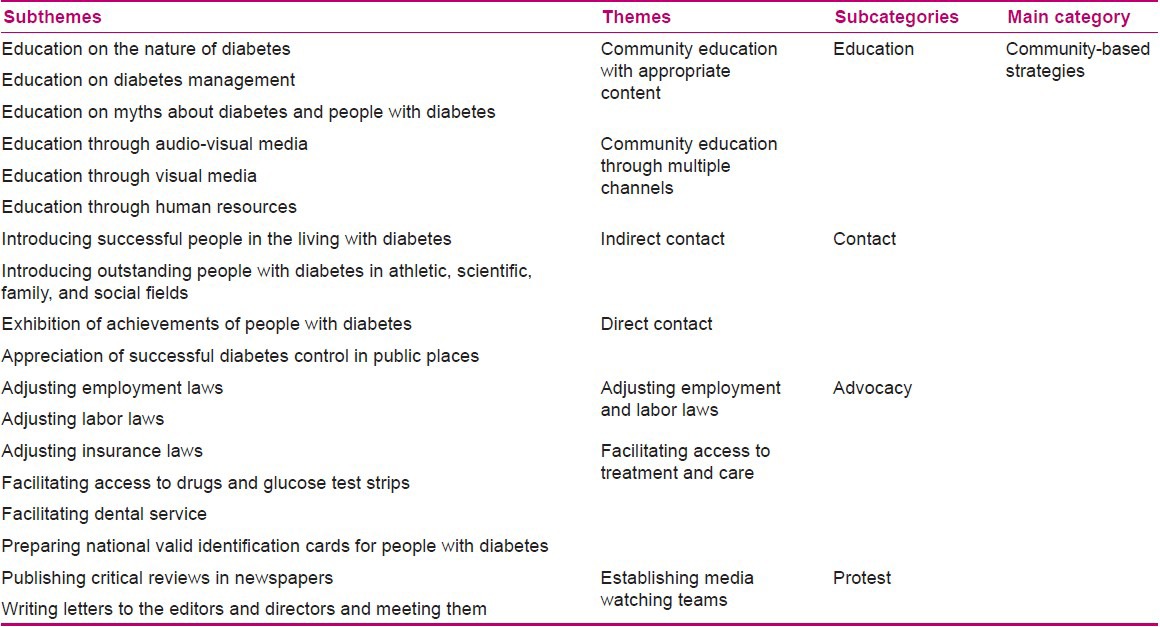

Participants pointed to several strategies and stated that any efforts to overcome diabetes-related stigma cannot be achieved without community-based strategies. Proposed community-based strategies were “education,” “contact,” “advocacy,” and “protest.” These strategies are mentioned in table 2.

Table 2.

community-based strategies to overcome diabetes-related stigma

Education

One of the main strategies mentioned was community education that should be done through the “appropriate content” and “multiple channels.”

Community education with appropriate content

Participants’ statements indicated that diabetes-related stigma was rooted in lack of knowledge. They believed that Iranian society has little information on the nature of diabetes and its management and transmission. Therefore, education and information about the “nature of diabetes,” “diabetes management,” and “myths about diabetes and people with diabetes” was the main stigma reduction strategy.

Participants believed that education about the “nature of diabetes” included “cause of diabetes,” “difference between type 1 and 2 diabetes,” “diabetes symptoms,” “transmission of diabetes,” and “controllable nature of diabetes.” For example, most participants referred to the one of the challenges in dealing with others. They stated that diabetes is considered a disease of the elderly, and community members are surprised when dealing with a child with T1DM. Not only people with diabetes, but also the non-affected population mentioned that it is necessary to educate people about the “difference between type 1 and 2 diabetes.” Two non-diabetic women of age 21 and 24 years, respectively, stated in a focused group thus:

“It is possible to explain it … many people do not know that young teens may have type 1 diabetes. They think that just elders have diabetes … you should inform people. I mean type 1 and 2 must be separate in their minds.”

Education about “diabetes management” included training on “insulin injection,” “hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia management,” “ability to use sweet food as possible,” and “recent news in the control and treatment of diabetes.” “Insulin injection” is one of the most important things considered strange and difficult by the society and sometimes results in misinterpretations. Thus, participants believed that the content of education should show insulin, its advantages, and injection to eradicate fears and misinterpretations. A 24-year-old man stated:

“My classmates ran away from me. They said he is injected. My blood sugar had fallen down a few times and I felt bad. Therefore, they ran away. It shocked me. It was like hitting people. You need to tell them everything.”

Sometimes the myths about diabetes and people with diabetes developed diabetes-related stigma. Participants referred to myths about the “impact of diabetes on menstruation and fertility” and “diabetes and aggression” that needed attention and correction. Therefore, an educational program should be designed to replace these myths with true and scientific information. For example, some participants said that people around them believed that diabetes could prevent the development of reproductive system and result in infertility. A 27-year-old woman with diabetes stated:

“You must tell them a diabetic person is a normal person. For example, it is a common belief that a diabetic girl could not have a baby, or it is difficult to marry her. It must be reformed. It must be said that they can get pregnant, they can get married.”

Community education through multiple channels

Participants mentioned multiple channels which can be used to increase the community awareness and therefore they can reduce diabetes-related stigma. These included a variety of media sources including “audio-visual media,” “visual media,” and “human resources.”

The audio-visual media sources mentioned were “radio and television,” “internet,” and “mobile phone.” “Radio and television” was named one of the most influential media for community education. However, participants indicated that the media policy must be planned in such a way to attract the society's attention and portray the empowerment and normal life of people with diabetes. They referred to a variety of programs, including the preparation of films on diabetes, to attract the audience's attention. A 28-year-old woman with diabetes said:

“I think good movies on cinema or television; I mean a well-made film is good idea. Such as a film titled ‘Man in orange dress,’ that portrays a good picture of sweepers. Such acceptable picture can portray people with diabetes … I do not know how, but I think it is necessary, since it is the most effective means to change culture and information. Therefore, moviemakers must give correct information.”

Visual media can be utilized for community education, which includes the “brochures,” “,” “newspapers,” “books,” “homework,” and “billboards.” For example, “billboards” can be used as efficient tools to attract the audience's attention. They can be used for public education. However, participants expressed the opinion that just the purposeful and planned use of billboards with simple visual message can be effective. Attractive photos and caricature, as well as short phrases must accompany the visual messages. A 27-year-old man expressed:

“You can draw a young man with diabetes who holds insulin in a workplace. Then write, ‘diabetes does not limit to work.’"

Human resources can also be used for community education. Based on our data, human resources are divided into two groups. One of the main sources is the healthcare team working in the diabetes centers that can teach in different places such as schools (courses for teachers, students, and parents), offices, cultural centers, parks, health centers, and mosques. According to the participants, religious leaders can educate the community on diabetes and fasting, and sin and disease efficiently. One of the staff of the selected diabetes center stated:

“People's attitude is bad. A woman said that since diabetes was diagnosed, my people do not get close to my kid. They thought we were the bad, and guilty. Diabetes is a punishment. These thoughts are common. It is necessary to tell them the facts. Clergy should say it.“

Contact

Establishing contact between people with and without diabetes was another strategy that emerged, which contained two classes, “indirect contact” and “direct contact.”

Indirect contact

Indirect contact through “introducing successful people in the living with diabetes” and “introducing outstanding people with diabetes in athletic, scientific, family, and social fields” was mentioned as a way for changing attitudes. In this way, people become familiar with people having a normal life and enjoying a fruitful and successful life despite having diabetes. Actually, a real example can contribute to the strengthening of education. Overall, community members should know that they are normal people like the rest and diabetes does not disrupt their life. One of the staff of a selected diabetes center said about the effectiveness of the introduction of empowerment people with diabetes thus:

“I think our culture must be improved. Do you remember that people's attitude about AIDS was terrible. It is better now. I think if we show people with type 1 diabetes in the TV show or at different places, it will be a condition that is more acceptable.“

Direct contact

The fear and stigma surrounding diabetes can be reduced through direct contact between people with and without diabetes. “Exhibition of achievements of people with diabetes” and “appreciation of successful diabetes control in public places” were mentioned as a tool to boost self-confidence of people with diabetes and to change community's attitude. A 25-year-old man without diabetes said:

“Fair for diabetics is useful. Alternatively, you can have a station in the other exhibition and show achievement of people with diabetes. Simultaneously you can distribute educational materials. So you teach. Diabetic's confidence will improve even if they did a little work… in addition, they are introduced as a diabetic. So, they never fear of disclosing their diabetes."

Advocacy

Attempt to defend the rights of people with diabetes was the other proposed strategy by the participants. These rights were their most important social challenges and were categorized as “adjusting employment and labor laws” and “facilitating access to treatment and care.”

Adjusting employment and labor laws

All participants who had attempted for employment mentioned that there are some restrictions for employing people with diabetes. In fact, they spoke about the stigma of employment law. Having no medical condition such as diabetes is a primary criterion in employment laws. It was stated by the participants that authorities should pay attention in this regard. A 22-year-old woman with diabetes believed that overcoming the stigma of laws is an effective way to reduce social stigma. She said:

“My first comment is for the government. When the government does not support us, I do not expect people… Public places do not hire us… so people say surely there is something wrong with diabetics. The government should solve problems. When people see that we are educated and we can work, they will understand the correct facts. It takes a long time, but it is very effective.“

Facilitating access to treatment and care

Another measure to protect the rights of people with diabetes and to reduce its related stigma is to facilitate access to treatment and care. This would mean “adjusting insurance laws,” “facilitating access to drugs and glucose test strips,” “facilitating dental services,” and “preparing national valid identification cards for people with diabetes.” For example, they mentioned national valid ID containing information such as name, age, picture, diabetes duration, type of treatment, and physician's name. Preparing and providing information to the public on this card can prevent arresting people with diabetes for drug addiction. In addition, people can help them during episodes of hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia. A 27-year-old woman with diabetes stated:

“Make a special and national card for a person with diabetes, so that everybody knows it. It helps them during bad events such as hypoglycemia. Firstly, it must be introduced through radio and television. Of course, you must be de-stigmatized. If there is any diabetes-related stigma, people with diabetes do not carry card. I mean de-stigmatization must be your first step and making a card must be your next step.“

Protest

The other item frequently expressed by the participants was diabetes-related stigma imposed by the media. The statements of all the participants demonstrated that it is necessary to establish media watching teams to review stigmatizing issues appearing in the media (such as newspapers, films, lyrics, television programs, etc.). Protests can be done through “publishing critical reviews in newspapers” and “writing letters to the editors and directors and meeting them.” For example, participants pointed to the examples of the stigmatizing films and programs and stated that they can be criticized and published in newspapers. A 27-year-old woman with diabetes, referring to the “bitter sugar,” said:

“It was as a bad movie… was about a little athletic boy who went to camps. He forgot insulin … it was about terrible times experienced by the boy and his mom. In my opinion, it demonstrated a bad picture of a person with diabetes. It must be reflected and criticized in newspaper. They should not show this film again.“

On the other hand, it is possible to write a letter to the people who create the stigmatizing programs (including the chief editor, program directors, etc.) and meet them. A 27-year-old man with diabetes said about writing letters to editors and directors thus:

“We can write a letter to the editor, director, etc., We can request for a meeting. Then we can talk with him on the subject and convince him as much as possible. Then he or she can correct the newspaper headline in the next issue, or the picture in the subsequent films.“

DISCUSSION

The results of the study showed that individuals with and without diabetes believed that overcoming diabetes-related stigma depends on reducing the social stigma. They believed that community-level strategies should be widely implemented in the long term. They mentioned several strategies including education, contacts, advocacy, and protest, which can improve the society's attitude toward people with diabetes.

Since diabetes-related stigma is rooted in lack of information, all participants mentioned “education” as a core component in all destigmatizing programs and activities. Participants’ statements and findings of Abdoli et al.’ study (2013)[19] indicated that Iranian community is not familiar with diabetes, especially type 1 diabetes, and they are afraid of diabetes. What they know about diabetes complications and what they do not know about the controllable nature of diabetes result in fear of the condition. Therefore, participants mentioned that it is necessary to plan people's education with appropriate training content via multiple channels.

Fukunaga et al. reported that participants experienced social stigma related to diabetes and felt that increasing the public's understanding of the disease would alleviate the social stigma.[20] Developing information campaigns aimed at increasing public awareness of diabetes and correcting the myths and misconceptions surrounding diabetes were mentioned as the goals by IDF.[15] Education is effective even in the short term, and should include a definition of disease, prevalence, symptoms, course of disease, biology, assessment and treatment, superstition, and true facts.[21] In most programs (such as HIV/AIDS-related stigma), education is a major component aimed at increasing knowledge, replacing false assumptions, and correcting stigmatizing behavior and attitudes. Education can be regarded as an important strategy, but with mixed results. The effectiveness of educational approaches can best be increased in combination with other approaches like contact and skills building. These strategies are found in several fields such as AIDS, leprosy, and epilepsy and share a common ground. Their differences lie in the content of the information provided and the groups at which the messages are targeted. Since stigmatization is a context-based phenomenon, the content of educational messages should be carefully considered and well adjusted to the context of stigmatized people.[22] Thus, although the literature on stigma mentioned education as a destigmatizing strategy, what distinguishes our finding is that it clearly expresses the effective available channels and appropriate educational content for the Iranian community. Participants cited a range of stigmatizing issues in diabetes that must be replaced with the facts, while so far no study has been done on this issue in diabetes. Participants believed that schools are the best target group. Literature reports on stigma also confirm these findings. It has been reported that students form a good and easily accessible group and often have a flexible attitude and behavior.[23,24]

“Direct and indirect contact” was another strategy that was obtained. Participants believed that true role models could eliminate the superstitions surrounding diabetes. This finding is also reported in other studies. Van der Meij and Heijnders stated that contact could be face to face or through the media. It has mixed results, but most studies on AIDS, epilepsy, and mental illness have shown positive results.[22] According to White, one of the most effective strategies to reduce social stigma is to increase interpersonal contact between mainstream citizens and members of the stigmatized group. As a vehicle of stigma reduction, contact is most effective when it is between people of equal status (mutual identification), is personal, voluntary, and cooperative, and is mutually judged to be a positive experience.[25]

“Advocacy” is another strategy that was mentioned by the participants to reduce diabetes-related stigma. Results indicate that advocacy through adjusting employment and labor laws and facilitating access to treatment and care can reduce the challenges of the patients in finding suitable jobs and can help in disease management and finally stigma. According to literature reports, advocacy is the way to change policies and discriminatory laws, and to better access to treatment and care.[22] Policies about how and where conditions are treated, divorce, immigration, employment policies, or banning people from public office, elections, or/and ownership can be stigmatizing.[26] Thornicroft also mentioned facilitating access to care and workplace adjustments as the necessary steps to overcome the stigma.[27] However, different aspects of the findings of the present study showed that participants believed that establishing a comprehensive equipped diabetes clinic is the key component to facilitate access to treatment and, thus, to overcome the stigma. Actually, they believed such a supportive source could reduce their problem, while this finding is contrary to the findings of other studies. For example, Deacon et al. reported that assigning a special clinic for HIV/AIDS can be a barrier to receiving services, since some people may not feel comfortable about coming to HIV/AIDS clinics.[28]

“Protest” was another strategy mentioned by the participants. They mentioned the role of media, especially television, in Iranian culture. They referred to some stigmatizing cases of diabetes in the media. These findings have also been reported in other studies. Protest highlights the injustice of specific stigmas and leads to a moral appeal for people to stop thinking that way. This approach may be effective in getting stigmatizing images removed from the advertisements, television, film, and other media outlets. Sometimes it has a rebound effect and its applications require a special attention. There are several avenues available for protesting against public stigma, including writing campaigns, phone calls, public denunciation, marches and sit-ins, boycott, etc.[21] There is little research on the impact or effectiveness of this approach. Some believe that it has only short-term positive effects on the attitude, and this issue needs further re search.[22]

So, as mentioned, although all the strategies are also used in other stigmatizing conditions, our findings are exclusively for diabetes and considering the Iranian culture. These findings have been obtained from a wide range of people (including people with and without diabetes). However, when planning to do these strategies, it should be noted that on one hand, the effectiveness of social strategies in different studies and different stigmatizing conditions is varied and many factors are involved. Stigma research has shown that these strategies should be implemented simultaneously at different levels to see structural changes in the society.[23] On the other hand, we must recognize that research on reducing health-related stigma has shown that changing attitudes and behavior has proved to be extraordinarily difficult. This is not good news, but it is a fact that must be acknowledged. Evidence suggests that individuals and their families should be involved in all aspects of planning and programs, and plans should be made according to local conditions.[29]

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, the active participation of people with diabetes and their strategies were discussed. When the strategies are derived from individual experiences and are culturally fitted, there is more hope for their effectiveness and sustainability. The results of this study can help the healthcare teams to integrate anti-stigma strategies in their care plan at a community level to reduce the stigma. We are looking forward to observe the effectiveness of these strategies in this ongoing action research. Limitations of this study are due to the inherent limitations of action research and qualitative studies. Therefore, it must be cautioned when the findings are generalized to other communities which has different context and culture.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research article is an extract from the PhD dissertation (No. 391088) of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The university approved and supported this study. We thank M. Adel Mehraban (faculty member of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences) who reviewed the inquiry for inquiry auditing as an independent qualitative researcher. In addition, we thank all the participants who took part in this study and shared their valuable experience.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schabert J, Browne JL, Mosely K, Speight J. Social stigma in diabetes: A framework to understand a growing problem for an increasing epidemic. Patient. 2013;6:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40271-012-0001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dwivedi A. Living on the outside: The impact of diabetes-related stigma. [Last accessed on 2008 Oct 07]. Available from: http://www.themedguru.com/articles/living_on_the_outside_the_impact_of_diabetes_related_stigma-86116061.html .

- 3.Goenka N, Dobson L, Patel V, O’Hare P. Cultural barriers to diabetes care in south Asians: Arranged marriage arranged complications? Practical Diabetes Int. 2004;21:154–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tak-Ying Shiu A, Kwan JJ, Wong RY. Social stigma as a barrier to diabetes self-management: Implications for multi-level strategies. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:149–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalra B, Kalra S, Sharma A. Social stigma and discrimination: A care crisis for young women with diabetes in India. Diabetes Voice. 2009;54:37–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amini P. Isfahan: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; 2003. Study of problems in children and adolesence living with diabetes from their mothers’ perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doosti Irani M. Isfahan: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; 2006. lived experience of people with type 2 diabetes. Thesis for masster degree in nursing. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abolhasani S, Babaie S, Eghbali M. Isfahan: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; 2008. Mothers experience about self care in children with diabetes. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdoli S. Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences; 2008. The empowerment process in people with Diabetes. Dissertation for PhD degree in nursing. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson MM. Limpopo Province, South Africa: University of Limpopo; 2010. The effect of stigma on HIV and AIDS tesing uptake among pregnant women in Limpopo province, in faculty of humanities (School of Social Sciences) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J. Stigma strategies and research for international health. Lancet. 2006;367:536–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Major B, O’Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopper S. Diabetes as a stigmatized condition: The case of low-income clinic patients in the United States. Soc Sci Med Med Anthropol. 1981;15B:11–9. doi: 10.1016/0160-7987(81)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiler DM, Crist JD. Diabetes self-management in a Latino social environment. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35:285–92. doi: 10.1177/0145721708329545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Diabetes Federation. A Call to Action on Diabetes, International Diabetes Federation, Nov. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balfe M, Doyle F, Smith D, Sreenan S, Brugha R, Hevey D, et al. What's distressing about having type 1 diabetes? A qualitative study of young adults’ perspectives. BMC Endocr Disord. 2013;13:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-13-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cross H, Heijnders M, Dalal A. Strategies for stigma reduction-part 2: Practical applications. Disability, CBR and Inclusive Development. 2012;22:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdoli S, Abazari P, Mardanian L. Exploring diabetes type 1-related stigma. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013;18:65–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukunaga LL, Uehara DL, Tom T. Perceptions of diabetes, barriers to disease management, and service needs: A focus group study of working adults with diabetes in Hawaii. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 18];Prev Chronic Dis. 2011 8:A32. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/mar/09_0233.htm . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson AC, Corrigan PW. Corrigan University of Chicago Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation; [Last accessed on 2012 Oct 14]. The Impact of Stigma on Service Access and Participation. A guideline developed for the Behavioural Health Management Project. Available from: http://www.bhrm.org/guidelines/stigma.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van der Meij S, Heijnders M. Soesterberg, The Netherlands: Proceedings of the International Stigma Workshop; November; 2004. The fight against stigma: Stigma reduction strategies and strategies, in international stigma workshop. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaebel W, Ahrens W, Schlamann P. German Alliance for Mental Health: Anti-stigma project; 2010. Conception and implementation of strategies to destigmatize mental illness-Recommendations and results of research and praxis. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen PD, Lubkin IM. United States: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2009. Chronic illness: Impact and strategies. [Google Scholar]

- 25.William W. Philadelphia: Department of Behavioural Health and Mental Retardation Service; 2009. Long-Term Strategies to Reduce the Stigma attached to Addiction, Treatment, and Recovery within the City of Philadelphia (With particular reference to Medication-Assisted Treatment/Recovery) [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Brakel W, Voorend C, Ebenso B, Cross H, Augustine V. London, Amsterdam: International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations (ILEP), Netherlands Leprosy Relief; 2011. [Last accessed on 2013 Jun 10]. Guidelines to reduce stigma: Guide 1 What is health-related stigma? p. 22. Available from: http://www.ilep.org.uk/fileadmin/uploads/Documents/Guidelines_to_Reduce_Stigma/ILEP_stigma_guidelines_-_1_web__2_.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Kassam A, Lewis-Holmes E. Reducing stigma and discrimination: Candidate strategies. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2008;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harriet Deacon, Inez Stephney, Sandra Prosalendis. South Africa: HSRC Press; 2005. Understanding HIV/AIDS Stigma: A Theoretical and Methodological Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Everett B, Stigma The hidden killer: Background paper and literature review. [Last accessed on 2013 Apr 08]. Available from: www.mooddisorderscanada.ca/Stigma/pdfs/STIGMA_TheHiddenKiller_MDSC_May2006.pdf.2006 .