Abstract

Background:

This study aimed to explore the role of social capital within the context of the nursing profession in Iran, based on the experience and perspectives of senior nursing managers.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted using the Graneheim and Lundman content analysis method. Using purposive sampling, 26 senior nursing managers from the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, the College of Nursing and Midwifery, the Iranian Nursing Organization, nursing associations and hospitals were selected, who participated in semi-structured in-depth interviews.

Results:

Content analysis revealed three main themes (social capital deficit, applying multiple strategies, and cultivating social capital) as well as eight categories which included professional remoteness, deficiency in professional potency, deficiency in professional exchanges, accumulation of personal social capital, accumulation of professional social capital, socio-political strategies, psychological–cognitive strategies, and ethical/spiritual strategies. The results show the perceived level of social capital in nursing in Iran, the application of some key strategies, and the principal rewards accrued from active participation in improving the social capital in nursing environment and profession.

Conclusions:

Efforts should be made to strengthen the social capital and apply key strategies with the aim of achieving personal and professional benefits for nurses, their patients, and co-workers, and for the delivery of healthcare in general. In this respect, the role of senior managers is vital in stimulating collective action within the profession, planning for the development of a culture of participation in healthcare services, helping to develop all fields of the profession, and developing and strengthening intra- and inter-professional exchanges and networking.

Keywords: Iran, nursing managers, qualitative research, social capital, social networks

INTRODUCTION

Health services involve mainly delivery of care through inter-personal interactions that are based on social variables.[1] Previous studies have indicated the existence of many social challenges within the nursing profession.[2,3] There are many concerns within the nursing profession related to professionalization,[4] professional power,[5,6] professional productivity,[7] nurses’ social image,[2] professional identity,[8,9] and inter-professional collaboration,[10,11] which could be improved or resolved by creating well-articulated and developed social relationships,[4,7] mutual understanding, effective interactions,[12] unification, adequate support, mutual trust,[4,5,9,13] and a participative environment.[2] Therefore, clarifying and building social capital within the field of nursing is, potentially, an important strategy for fostering safer and more effective healthcare interactions.[14]

Identifying the nature and extent of social relations is generally a question closely associated with understanding social capital.[15] Social capital has several definitions, all of which focus on the value of social networks, the bonds, bridges, and links between people, as well as trust and reciprocity.[16] Social capital has been recognized as an important investment for maximizing profit within organizations and has been shown to be associated with beneficial outcomes, performance improvement, and better decision making.[17,18]

A systematic review showed that inter-professional relations within the nursing profession were linked to improved care outcomes.[19] In addition, higher levels of teamwork have been shown to be associated with higher levels of nurse-assessed quality of care and better patient satisfaction.[20]

While much attention has been paid to building leadership ability and the overall role of managers, in improving healthcare outcomes, a shift in focus onto the quality of social relationships within and between professional groups has been suggested.[21] Although social capital and health have been the subject of many studies, the field of social capital research is still in its infancy and there remains much work to be done.[14,22,23] Some studies indicate that an individual's social capital is a significant predictor of overall job satisfaction,[24] as well as an important factor in strengthening effective clinical risk management.[25]

Despite increasing attention being paid to the impact of social capital within health systems, few studies have specifically examined the role of social capital in nursing. Thus, an important area for research is to assess nurses’ perspectives on the presence and use of social capital and how it may enable better interactions and outcomes in the provision of care. This could be the first crucial step for policy makers, managers, and educators when designing programs aimed at empowering nurses. This study aimed to explore current issues in the identification and use of social capital in the nursing profession in Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a qualitative study that used a naturalistic, interpretive approach concerned with understanding the meanings that people attach to social phenomena.[26]

The study was conducted between December 2011 and May 2012. Twenty-six senior nursing managers (15 women and 11 men) from the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education, the Iranian College of Nursing and Midwifery, the Iranian Nursing Organization, and nursing associations and hospitals in Tehran participated in the study. Participants were selected using purposive sampling.[27] All participants had extensive professional and managerial backgrounds and regularly participated in decision making in relation to nursing and healthcare reforms.

Data were collected through semi-structured, in-depth interviews. Interviews ranged between 45 and 90 min in duration. Interviews and data analysis continued until a saturation point was reached.[28] Participants gave permission for audio recording of the interviews which were then transcribed verbatim.

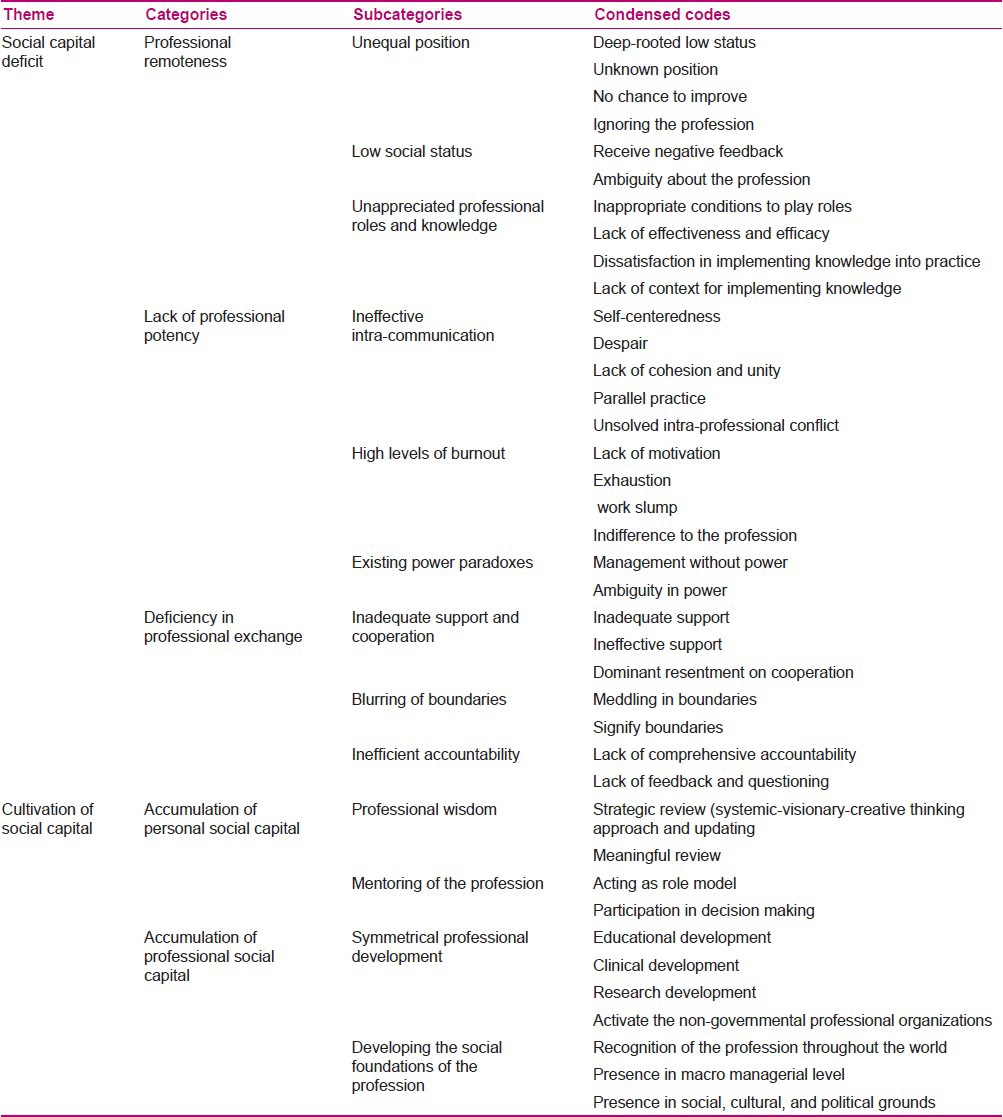

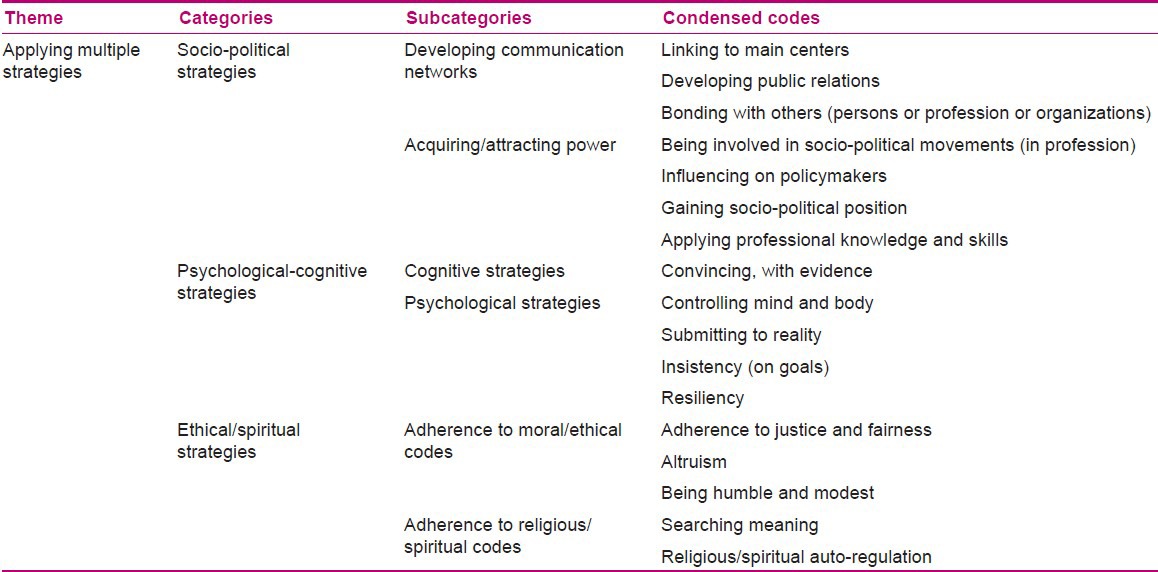

Interviews were analyzed using the Graneheim and Lundman content analysis method.[29] The units of analysis were the individual interview transcripts. Interviewers asked questions relating to various aspects of professional participation. Questions relating to participants’ experiences and perceptions included, “please tell me about your work experiences,” “how do you perceive the social capital of your profession?,” and “how have you contributed to improve it?” Each interview was read several times in order to give a holistic perspective. Then, the interview transcript was divided into two categories: positive experiences and negative experiences relating to the social climate of the profession. Following this, the sections relating to participants’ positive and negative experiences were extracted and combined into three texts, which constituted the unit of analysis. The sections of text were divided into units of meaning that were then condensed. The condensed meaning units were then abstracted and coded. The various codes were compared based on the differences and similarities between them and then sorted into 23 sub-categories and 8 categories, which constituted the manifest content of the interviews. The tentative categories were discussed by two other researchers and revised. A process of reflection and discussion led to an agreement about how to sort the codes. Finally, the core meaning, i.e. the latent content, of the categories was categorized into three themes. Examples of condensed codes, sub-categories, categories, and the three themes are given in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Summary of theme, categories, subcategories, and condensed codes

Table 2.

The theme, categories, subcategories, and condensed codes

Lincoln and Guba's criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, and conformability were employed in order to increase rigor.[28] Trustworthiness of the results was obtained by prolonged engagement with the subject of study, reviewing participants’ interviews, having a maximum variation in the participants, by the review of interviews, codes, and categories by the research team, and by peer-review procedures. Peer review was conducted by four faculty members who had nursing and qualitative research experience. Many of the interviews and codes were reviewed using this process. Furthermore, the results were shared with other managers not involved in the research, who confirmed that there were similarities between their experiences and the study results.

Ethical considerations

Before beginning the study, ethics approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee. The second author informed the participants about the purposes of the study, the right to withdrawal from the study at any stage, and gave assurances about their anonymity. In addition, written consent was obtained from all participants. All interviews were performed in a private room with ensured privacy and confidentiality. In addition, all audio files and interview transcripts were stored in the second author's password-protected computer.

RESULTS

Content analysis revealed three main themes, (1) social capital deficit, (2) the application of multiple strategies, and (3) cultivating social capital, as well as eight subcategories [Tables 1 and 2]. These categories indicated perceived social capital in nursing, the application of key strategies for coping, and the rewards from active participation in improving social capital.

Social capital deficit

This theme related to a negative perception of professional status, professional power, and a lack of appropriate reciprocity among nurses and other healthcare workers.

Professional remoteness indicates nurses’ professional separation from their status and potency in the Iranian healthcare system and society. Some of the participants’ statements in relation to this theme are presented below.

Unequal position:

“From the very beginning, our status in nursing was not good. Our status is not clear. There is no any chance or context for us.”

Low social status:

“People express to me this message: I do not see your importance in the community.”

Unappreciated professional roles and knowledge:

“The professional nurse has eight roles; however, the situation is not like you feel you offer a service and that you have a significant role.”

The notion of a lack of professional potency seemed to dominate and exhaust the nurses. The study revealed that this condition originates from social factors such as ineffective intra-professional communication, burnout, and existing power paradoxes. Some selected interview extracts are presented below.

Ineffective intra-professional communication:

“Our biggest obstacle is the lack of cohesion and unity.”

High levels of burnout:

“In nursing, there is a state of severe exhaustion and leaving work. In nursing, I feel there is a sense of inferiority.”

Existing power paradoxes:

“The most important problem is this fact, for instance, I choose a manager, but the manager does not have power. S/he does this as a tool.”

Deficiency in professional exchanges revealed weak coordination and inadequate support, inefficiencies within systems of accountability, and a blurring of organizational boundaries that detracted from the profession's mutuality in achieving its professional goals. Selected interview extracts are presented below:

Inadequate support and cooperation:

“Superiors don’t give us any support. Generally they are not very inspiring in this process. There is resentment instead of cooperation in the profession.”

Blurring of boundaries:

“One of the things which causes me not to cooperate with them is they meddle a lot.”

Inefficient accountability:

“In our country, comprehensive accountability system has not found a place to meet the people's expectations yet. They (authorities) never look at you, how you work that can have an output with quality, how you would do, who knows?…, I’m sorry, anyone does not know!”

Applying multiple strategies

Applying multiple strategies refers to applying socio-political, psycho-cognitive, and ethical/spiritual strategies to confront perceived social capital deficits within the profession. The themes, categories, subcategories, and condensed codes are presented in Table 2.

Socio-political strategies focused on developing two socio-political concepts: communication and power. Psycho-cognitive strategies were generally used for adaptation and agreement at times of perceived powerlessness, to calmly consider how conditions may impact others and to facilitate access to goals. Ethical/spiritual strategies were based on justice and fairness, altruism, modesty and humility, searching for meaning, and religious auto-regulation. The participants claimed that the application of ethical/spiritual strategies is useful for facilitating humanistic relationships and for preventing damage to human resources.

Some samples of the participants’ statements are presented below.

Developing communication networks:

“The success, that I had obtained, was due to developing communications with the centres that had impact on the profession.”

Acquiring/attracting power:

“By our social political movements, we get the strength or power to change. We tried to influence on people who were significant decision makers in our profession.”

Cognitive strategies:

“When we do not have any effective power, the most important way is that arrange in a line the others with ourselves, by evidence.”

Psychological strategies:

“So in every hard time, I tried to control getting emotionally upset, for positive effect on other. I always try to go along with the real.”

Adherence to moral/ethical codes:

“I try to be modest and humble. Ever helps me God.”

Adherence to religious/spiritual codes:

“I based my work on justice and fairness. I believe opportunities must be equally spread in the system ….”

Cultivation of social capital

This theme reflects the personal and professional rewards for the participants’ efforts to improve and enhance social capital.

The accumulation of personal social capital reflects two personal rewards: professional wisdom and mentoring within the profession. Data analysis reveals that professional wisdom is a type of thinking that includes strategic and meaningful review of the profession. Strategic review was conducted using a systemic, visionary, and creative approach. Some interview extracts relating to this are given below.

Strategic review

Systemic review:

“… therefore, it is true that establishing a bank for the nurses is an economic activity, but this is in accordance with the systemic view since financial assistance is a need for every family, and as a nurse, I should work and think about it. This fact is not really separated from nursing.”

Visionary review:

“I do not know whether this goal is achievable or not, but it is my noble objective. Truly it was in cartoon clouds of my thought.”

Creative reviewing:

I think about intelligence, creativity in nursing. We need to do a new work in nursing. I always try to keep myself up to date; I look at the new paradigm. I do not like to think traditionally.”

Meaningful review:

“… So I feel same as all those people who have knowledge and commitment. I could not ignore my understanding because understanding and commitment always come hand in hand. Those are mixed. If on the Day of Judgment, the nurse appears as a person and tells me, ‘what have you done with my rights.,’ I have to answer it.”

In addition, data analysis revealed that participants have contributed to mentoring the profession and view this as a worthwhile informal and formal contribution. The study revealed that senior nurse managers view the nursing profession as a “mentee” that may benefit from their leadership. This indicates that they strive to lead their profession and to achieve their goals by acting as a role model and participating in decision making at both the micro- and macro-level with these goals in mind [Table 1]. The participants’ statements relating to this topic are presented below.

Mentoring the profession

Acting as a role model:

“Especially I think when a person acquires a lot of experience and works honestly, others feel and want to be a role model. I have always tried to be a role model; many persons told me that I am their role model.”

Participation in decision making:

“We made decisions in council. Although we consider many decisions according to policy makers, there were some cases that we resisted based on our thoughts and professional viewpoints.”

As a response to experiencing social capital deficit, participants accumulated social capital, which then helped them to contribute to symmetrical professional development and building the social foundations of the profession. Symmetrical professional development refers to the reward accrued from the collective efforts of managers in developing all areas of nursing, such as education, clinical practice, management, research, and community. The subcategories in Table 1 show this. Developing the social foundations of the profession appears to lead to other professional rewards that are gained from active participation in strategies and individual actions whose goal is to assuage the social capital deficit. The subcategories in Table 1 show the new grounds for nursing in Iran. These subcategories show some of the social outcomes for nursing in the Iranian context that may be gained from the participants by collective efforts and social networking.

DISCUSSION

The three main themes identified in this study reveal the participants’ experiences and perceptions of nursing social capital. Primarily, the study shows that participants had negative perceptions and experiences of their professional social capital, and because of these, they applied multiple strategies, both individually and collectively, for cultivating social capital for the nursing profession in Iran.

Status is seen as a form of social capital.[16] In this regard, many studies have shown that the status of nursing within the Iranian healthcare system and society is insufficient.[2,5] Some studies have found that certain factors, such as poor social image and social problems, negatively affect the perception of the profession,[30] identified as an issue that disables the impact of the nursing profession throughout the world. In addition, there was an ineffective intra-professional communication between the nurses, as quoted by the study participants. Social capital is commonly defined in terms of features of social relationships, such as levels of inter-personal trust and norms of reciprocity and mutual aid that facilitate collective action for mutual benefit.[31] Some researchers have assumed that mutual understanding, escape from misunderstandings, and collaborative communication are the qualities associated with good communication that are negatively associated with conflicts within groups.[12,32,33] Furthermore, one study showed that low levels of social capital, evinced by mistrust and lack of reciprocity at work, had adverse effects on self-rated healthcare among healthcare workers.[34] These studies showed that low social capital levels inhibited the development of nursing as an authoritative and impactful profession with new ideas.[35] The participants in this study perceived that burnout and frustration with the tendency for their ideas to be dismissed or their innovations to be unsupported constrained the nursing workforce. Studies have revealed that burnout is a symptom of many work and work culture problems and is accompanied by many poor outcomes including increased absenteeism, reduction in service quality, and increased workplace stress.[36,37] Other studies have shown that the predictors of emotional exhaustion in hospitals are low self-efficacy and subjective low levels of social capital.[38] Additionally, in nursing, high social capital is negatively correlated with nurses’ risk of emotional exhaustion.[39] Data analysis confirmed the existing paradox of power that led to defects in the abilities and potency of the profession. Other studies have supported this conclusion. For example, despite being the largest workforce in the healthcare delivery system, nursing are considered to be the “weakest” profession.[5] In addition, many nurses are dissatisfied with the lack of power and autonomy to control their own professional practice and believe that despite expressing their strengths, clinicians and managers do not respect their decisions.[40] A qualitative study of the perception and experience of power also revealed that power in nursing was influenced by social, professional, and organizational variables that include: application of knowledge and skills, having authority, being self-confident, unification and solidarity, being supported, and organizational culture and structure.[5] The category “deficient professional exchange” indicated ineffective exchange due to inadequate cooperation and support, inefficient accountability systems, and a blurring of organizational boundaries, as well as the obstacles to reciprocity based on trust in the profession. Concepts such as cooperation, support, and trust are the main elements of social capital. Many studies have emphasized the importance of these qualities in the nursing work environment and how they relate to nursing identity, skills, and expertise in improving patient care.[41,42]

In addition to providing support and encouragement for nurses and valuing professional staff, managers are the facilitators of development within the profession. Studies have shown that inadequate support is a common obstacle to the professional growth and development of nurses.[43] The inefficiency of accountability systems refers to the perceptions and experiences of the participants of working without getting any positive feedback. In addition, the participants highlighted the importance of accountability among all healthcare workers and managers, not only nurses. The concept of accountability is closely related to communication, public trust, confidence in healthcare, and autonomy,[44,45] and is an influencing factor on the working environment. Accountability leads to empowerment and a sense of personal efficacy.[45] This study also showed that the blurring of organizational boundaries inhibited intra-organizational exchanges between governmental and non-governmental nursing organizations. Boundaries and territorial behaviors are important aspects of organizations. The members of an organization can and do become territorial over physical spaces, ideas, roles, relationships, and other potential possessions within their organization.[46,47] Our analysis indicated, for example, dissatisfaction about the blurring of organizational boundaries between governmental and non-governmental nursing organizations, which acted as an obstacle to reciprocal exchange.

The results of the present study are similar to those of studies conducted in other regions of Iran and give an overview of the issues and problems in the nursing profession in Iran. Despite the fact that nurses face problems in the workplace, they generally try to complete their roles and main tasks. The term “resilience” probably most fittingly describes the attitudes and actions of this group. Studies have shown that despite the adverse working conditions in nursing, many nurses choose to remain in nursing; also, they survive and even thrive despite being in a climate of workplace adversity.[48] Our findings show that although participants view the overall social capital in the profession in a negative light, they also use multiple strategies to try and improve and refine the situation. The study revealed the strategies that some of the participants use. Strategy is commonly defined as a mode of action for achievement of a main goal when the available resources are insufficient.[49] In fact, the application of these strategies by the senior nurse managers revealed their attention and knowledge related to ethical, spiritual, cognitive, psychological, and socio-political aspects of action, including strategies for the use of scarce resources. Similar to our results, other nursing studies have emphasized the importance of justice and fairness,[50] psychological and cognitive coping mechanisms,[51] socio-political actions,[52,53,54] and adherence to ethical/spiritual codes.[50,55]

This study showed that a sense of wisdom was a personal gain related to the efforts to improve social capital within the profession. The nursing environment is a factor related to the learning and development of senior managers.[56] Some scholars believe that difficult experiences can result in growth and “wisdom” is a consequence of coping with adverse conditions.[57] The opportunity to mentor within the profession was another personal reward. Mentoring has various definitions and interpretations in the social, organizational, and educational fields.[58] Content analysis revealed that mentoring was undertaken by acting as a role model and participating in decision making related to the nursing profession. A review of the published literature indicated that a mentor functions both as a role model[58] and as a counselor in decision making for professional development.[59,60] This study showed that achieving the position of mentor was a consequence and a reward arising from actively attending and being mindful in the profession. The participants in this study emphasized on collective efforts to promote symmetrical professional development in all fields of the profession and to develop stronger social foundations for the profession. Studies have shown that despite its challenges and obstacles, the nursing profession has improved in recent years.[2] Also, this study demonstrates the basis for some of these improvements. In addition, the analysis revealed that social capital has both negative and positive aspects within the nursing profession and these depend highly on the active participatory role of individual nurses.

CONCLUSION

The concept of social capital appears to be valuable for the development of healthcare organizations. The study results indicate that social capital can be improved in nursing by encouraging collective efforts, applying multiple strategies, expanding communication networks, creating a supportive work environment, improving accountability in the healthcare system, creating clear organizational boundaries, and modifying power structures. The role of senior managers is vital in achieving these goals. In addition, we believe that it is necessary to conduct further quantitative and qualitative studies to test and develop strategies, explore the tools used to measure social capital, and foster a deeper understanding of the process of improvement of social capital within the nursing profession.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to acknowledge all the senior nurse managers, whose participation has enabled us to write this article.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was carried out as part of a PhD dissertation by Hamideh Azimi Lolaty, that funded by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Salvatore D. Physician social capital: Its sources, configuration, and usefulness. Health Care Manage Rev. 2006;31:213–22. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200607000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farsi Z, Dehghan-Nayeri N, Negarandeh R, Broomand S. Nursing profession in Iran: An overview of opportunities and challenges. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2010;7:9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2010.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varaei S, Vaismoradi M, Jasper M, Faghihzadeh S. Iranian nurses self-perception-factors influencing nursing image. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20:551–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Habibzadeh H, Ahmadi F, Vanaki Z. Facilitators and Barriers to the Professionalization of Nursing in Iran. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2013;1:6–25. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagbaghery MA, Salsali M, Ahmadi F. A qualitative study of Iranian nurses’ understanding and experiences of professional power. Hum Resour Health. 2004;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sneed NV. Power: Its use and potential for misuse by nurse consultants. Clin Nurse Spec. 1991;5:58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehghan Nayeri N, Nazari AA, Salsali M, Ahmadi F, Adib Hajbaghery M. Iranian staff nurses, views of their productivity and management factors improving and impeding it: A qualitative study. Nurs Health Sci. 2006;8:51–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2006.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts SJ. Development of a positive professional identity: Liberating oneself from the oppressor within. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2000;22:71–82. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200006000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaismoradi M, Salsali M, Ahmadi F. Perspectives of Iranian male nursing students regarding the role of nursing education in developing a professional identity: A content analysis study. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2011;8:174–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2010.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M, San Martin Rodriguez L, Beaulieu M-D. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: Core concepts and theoretical frameworks. J Interprof Care. 2005;19:116–31. doi: 10.1080/13561820500082529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irajpour A, Alavi M, Abdoli S, Saberizafarghandi MB. Challenges of inter professional collaboration in Iranian mental health services: A qualitative investigation. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17:190–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehghan Nayeri N, Negarandeh R. Conflict among Iranian hospital nurses: A qualitative study. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rafii F, Oskouie F, Nikravesh M. Factors involved in nurses’ responses to burnout: A grounded theory study. BMC Nurs. 2004;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh CH. A concept analysis of social capital within a health context. Nurs forum. 2008;43:151–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2008.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott C, Hofmeyer A. Networks and social capital: A relational approach to primary healthcare reform. Health Res Policy Syst. 2007;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Royal J. Evaluating human, social and cultural capital in nurse education. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;32:e19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King NK. Social capital and nonprofit leaders. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh. 2004;14:471–86. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad Manage Rev. 1998;23:242–66. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2008;38:223–9. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000312773.42352.d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meterko M, Mohr DC, Young GJ. Teamwork culture and patient satisfaction in hospitals. Med Care. 2004;42:492–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000124389.58422.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammer A, Ommen O, Röttger J, Pfaff H. The relationship between transformational leadership and social capital in hospitals-a survey of medical directors of all German hospitals. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2012;18:175–80. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31823dea94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmeyer A, Marck PB. Building social capital in healthcare organizations: Thinking ecologically for safer care. Nurs Outlook. 2008;56:145–9. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Looman WS, Lindeke LL. Health and social context: Social capital's utility as a construct for nursing and health promotion. J Pediatr Health Care. 2005;19:90–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ommen O, Driller E, Köhler T, Kowalski C, Ernstmann N, Neumann M, et al. The relationship between social capital in hospitals and physician job satisfaction. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:81. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ernstmann N, Ommen O, Driller E, Kowalski C, Neumann M, Bartholomeyczik S, et al. Social capital and risk management in nursing. J Nurs Care Qual. 2009;24:340–7. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3181b14ba5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritchie J, Lewis J. United States: Sage Publications Limited; 2003. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative; pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polit DF, Beck CT. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010. Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikbakht Nasrabadi A, Emami A. Perceptions of nursing practice in Iran. Nurs Outlook. 2006;54:320–7. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clays E, Clercq B. Individual and contextual influences of workplace social capital on cardiovascular health. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2012;34:177–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox KB. The effects of unit morale and interpersonal relations on conflict in the nursing unit. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35:17–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell GJ. A qualitative study exploring how qualified mental health nurses deal with incidents that conflict with their accountability. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2001;8:241–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2001.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki E, Takao S, Subramanian SV, Komatsu H, Doi H, Kawachi I. Does low workplace social capital have detrimental effect on workers’ health? Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1367–72. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Domajnko B, Pahor M. Mistrust of academic knowledge among nurses in Slovenia. Int Nurs Rev. 2010;57:305–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kowalski C, Driller E, Ernstmann N, Alich S, Karbach U, Ommen O, et al. Associations between emotional exhaustion, social capital, workload, and latitude in decision-making among professionals working with people with disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2010;31:470–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sundin L, Hochwälder J, Bildt C, Lisspers J. The relationship between different work-related sources of social support and burnout among registered and assistant nurses in Sweden: A questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44:758–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Driller E, Ommen O, Kowalski C, Ernstmann N, Pfaff H. The relationship between social capital in hospitals and emotional exhaustion in clinicians: A study in four German hospitals. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57:604–9. doi: 10.1177/0020764010376609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kowalski C, Ommen O, Driller E, Ernstmann N, Wirtz MA, Köhler T, et al. Burnout in nurses: The relationship between social capital in hospitals and emotional exhaustion. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:1654–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nasrabadi AN, Lipson JG, Emami A. Professional nursing in Iran: An overview of its historical and sociocultural framework. J Prof Nurs. 2004;20:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fagerberg I, Kihlgren M. Experiencing a nurse identity: The meaning of identity to Swedish registered nurses 2 years after graduation. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34:137–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.3411725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerrish K. Still fumbling along? A comparative study of the newly qualified nurse's perception of the transition from student to qualified nurse. J Adv Nurs. 2001;32:473–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahimaghaee F, Dehghan-Nayeri N, Mohammadi E. Iranian nurses perceptions of their professional growth and development. Online J Issues Nurs. 2010;16:10. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No01PPT01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milton CL. Accountability in nursing reflecting on ethical codes and professional standards of nursing practice from a global perspective. Nurs Sci Q. 2008;21:300–3. doi: 10.1177/0894318408324314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wade GH. Professional nurse autonomy: Concept analysis and application to nursing education. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30:310–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown G, Lawrence TB, Robinson SL. Territoriality in Organizations. Acad Manage Rev. 2005;30:577–94. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daly WM, Carnwell R. Nursing roles and levels of practice: A framework for differentiating between elementary, specialist and advancing nursing practice. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:158–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson D, Firtko A, Edenborough M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. [Last accessed on 2013 Feb 13]. Available from: http: www.en.wikipedia.org. Strategy.Wikipedia: The free encyclopedia: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Available from: http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategy .

- 50.St-Pierre I, Holmes D. The relationship between organizational justice and workplace aggression. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:1169–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lambert VA, Lambert CE. Nurses’ workplace stressors and coping strategies. Indian J Palliat Care. 2008;14:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Des Jardin KE. Political involvement in nursing-politics, ethics, and strategic action. AORN J. 2001;74:614–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fyffe T. Nursing shaping and influencing health and social care policy. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17:698–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Primomo J. Changes in political astuteness after a health systems and policy course. Nurse Educ. 2007;32:260–4. doi: 10.1097/01.NNE.0000299480.54506.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Golberg B. Connection: An exploration of spirituality in nursing care. J Adv Nurs. 2002;27:836–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gopee N. Human and social capital as facilitators of lifelong learning in nursing. Nurse Educ Today. 2002;22:608–16. doi: 10.1016/s0260-6917(02)00139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Plews-Ogan M, Owens JE, May NB. Wisdom through adversity: Learning and growing in the wake of an error. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91:236–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bozeman B, Feeney MK. Toward a useful theory of mentoring a conceptual analysis and critique. Adm Soc. 2007;39:719–39. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anthony MK. The relationship of authority to decision-making behavior: Implications for redesign. Res Nurs Health. 1999;22:388–98. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199910)22:5<388::aid-nur5>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krairiksh M, Anthony MK. Benefits and outcomes of staff nurses’ participation in decision making. J Nurs Adm. 2001;31:16–23. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]