Abstract

Background:

This study aims to explore the relationship between religiosity and psychological well-being of caregivers of stroke survivors in Shiraz, Iran.

Materials and Methods:

A purposive sample of 96 family members, which included 34 daughters-in-law and 62 daughters, who were caring for severe impaired stroke survivors were enrolled in the study.

Results:

The results showed a significant correlation between positive religious coping and caregivers’ psychological well-being. Positive religious coping accounted for 7.2% of the change in psychological well-being. There was no significant association between demographic factors and caregivers’ psychological well-being.

Conclusions:

Our results indicated that religious and spiritual belief have a role in caregiver adaptations with the situation. Therefore, in future studies, it is suggested to concentrate on the effects of other characteristics than the demographic variables on psychological well-being.

Keywords: Aging, caregivers, mental health, religious coping, stroke

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is an important public health problem and one of the most frequent causes of death and frailty globally.[1] Stroke usually creates a range of disabilities such as (i) physical deficits with ambulation, transfer, bowel and bladder incontinence, and difficulty in performing daily activities; (ii) cognitive changes such as disturbances in thought and memory loss; and (iii) psychosocial problems like anxiety and depression.[2] Family caregivers play a significant role in home care and usually carry out difficult care responsibilities[3] such as administering medicines, feeding, bathing, dressing, toileting, providing help in moving, transportation, managing medical appointment, as well as providing emotional and financial support.[4] Caregivers should rapidly learn how to help stroke survivors with a range of deficits and simultaneously adjust with the alterations in their own life that arise as a consequence of caregiving.[5]

Since stroke is an unanticipated shocking incident that abruptly necessitates caregiving role of the patients’ family members caregivers usually experience an overwhelming sense of burden, depression, and decline in physical and emotional health.[6] Previous studies have shown that female caregivers, especially daughters and daughters-in-law, experience the greatest adverse emotional and physical health consequences of parent caregiving because of their multiple social roles in addition to the caregiving demands.[7,8,9] These negative consequences have been a matter of concern for the researchers and policy makers because they overlap with the caregivers’ self-care and with their capability to constantly provide sufficient care to dependent elders.[10] Brody[11] argued that the burden these women perceive arises not only from multiple roles, their time and energy, but also from the psychological dimension of their status.

Often, when individuals are confronted with hardships, including serious and life-threatening situations (such as stroke), they turn toward a higher power or religion as a method of coping.[12] Religion and spirituality's positive effects have been identified as contributing to caregiver's sense of well-being and coping.[13] Studies have clarified distinctive valuable association between religion and well-being among caregivers. Fenix et al.[14] found that caregivers who considered themselves to be religious suffered a lower incidence of major depression. Caregivers’ beliefs increased their ability to cope and this faith motivated their decision to tolerate many of the hardships of caregiving.[15] Gall et al.[16] demonstrated that religious coping accounted for 14% of the change in psychological well-being and 16% of the discrepancy in life satisfaction compared to non-religious coping strategies. Religion was reported to offer a set of beliefs that assist to find the meaning and goal of negative situation, as well as a gives a feeling of hope, harmony, and consistency, assisting in acceptance and adaptation.[17] The most significant point is the form of religious coping which has been applied. Positive religious coping has been defined as a set of strategies that include appraising a secure relationship with a benevolent God, a belief that there is meaning in life and seeking support from clergy/church members.[18]

Several studies have focused on religious coping among patients with cancer and other life-threatening illnesses. Despite growing work in this area, little is known about religious coping and its health implications among family caregivers.[19,20] Thus, there is a need to understand how family caregivers draw on their faith to help manage these demands. Understanding how religion affects the experience and well-being of caregivers is essential for determination of future interventions. In addition, limited studies have compared the blood ties and affinal relationship in caregiving (related by marriage).[7,21] Therefore, this study aims to explore the relationship between religiosity and psychological well-being of daughters and daughters-in-law caregivers of stroke survivors in Shiraz, Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research design

A descriptive correlation design was applied to identify the relationship between religious coping strategies and psychological well-being of caregivers of stroke patients.

Sample

A purposive sample of 96 caregivers of severely disabled stroak survivors completed the questionnaires during patient hospital stay. A power analysis was performed to identify the number of participants required for statistical significance. To perform multiple regression, with a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) and a power of 0.80, a sample of 92 participants was calculated by using G*Power 3.1.2 software. An additional four subjects were added for attrition rate. A purposive sample of 96 family members, which included 34 daughters-in-law and 62 daughters who were caring for severe impaired stroke survivors, was selected to test the research hypothesis. Caregivers of stroke survivors, who had first diagnosis of ischemic stroke and were of age ≥60 years with severe functional dysfunction (Modified Rating Scale 4-5 and Barthel Index 0-9), were enrolled in the study. The caregivers had to be daughters or daughters-in-law for whom taking care of the stroke survivors was the primary responsibility. They had to live in the same house with the survivors and had to be 18 years and over. Participants were recruited from the neurological departments of two large referral hospitals affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (SUMS) in Shiraz, Iran.

Research hypotheses

H1: Causal antecedents (caregiver characteristics) will positively predict the psychological well-being of stroke caregivers.

H2: Levels of religious coping would strongly correlate with the levels of caregivers’ psychological well-being.

Measures

Antecedent factors

These included caregiver characteristics that were measured using demographic data sheet. Caregiver demographic information included the type of relationship, age, education level, marital status, family size, number of children, employment status, perceived economic status, perceived health, and living arrangement before stroke.

The religious coping styles

The religious coping style was measured by the Brief Religious Coping Scale (Brief RCOPE),[18] which is a 14-item instrument, and each item is scored by a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a great deal). This scale assesses both positive and negative religious coping behaviors. Items 1-7 measure positive religious coping and items 8-14 assess negative religious coping. The scale revealed acceptable internal consistencies (i.e. Cronbach's alpha = 0.79) in the present study.

Psychological well-being

Caregiver psychological well-being was assessed based on the score of the 18-item Index of Psychological Well-being.[22] This scale evaluates six significant dimensions of psychological well-being that consist of (a) autonomy, (b) environmental mastery, (c) purpose in life, (d) personal growth, (e) positive relations with others, and (f) self-acceptance. The items were scored on a 6-point Likert scale from (1) strongly disagree to (6) strongly agree. Generally, the score is in the range of 18-108 and higher scores indicate better psychological well-being. In this study, the internal consistency was 0.76, and for each subscale, it was 0.72-0.88.

Translation

The Brief RCOPE and Index of Psychological Well-being scales were used for the first time in Iran. These instruments were translated into Persian by the researchers. The translation results were offered to a panel of three professors who were experts in English language for review. After revision, an English professor translated the Persian language version back into English. After translation, a pilot study was conducted on a sample of 30 family members of stroke patients to identify the internal consistency, feasibility, and stability of the instruments. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for both scales was found to be acceptable and was easily understood by the Iranian family caregivers who participated in the pilot study.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study population, including count, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. Also, the normality of distribution was evaluated. Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was used to study the correlation between quantitative variables and Spearman correlation coefficient was used for qualitative variables. The level of significance selected for this study was P ≤ 0.05. Multiple regressions were used to find which variables are most important in explaining changes in the dependent variable (psychological well-being).

RESULTS

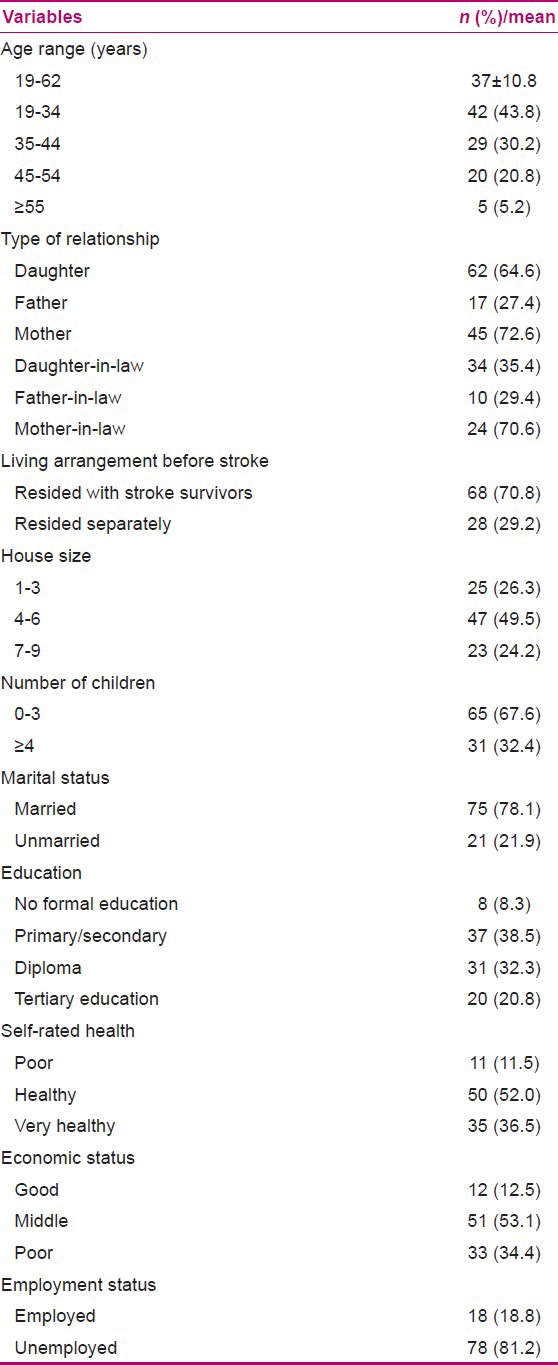

A total of 96 caregivers of stroke survivors who met the study criteria served as subjects in the study. Table 1 provides the description of the sample based on the selected demographic characteristics. As shown in Table 1, caregivers ranged in age from 19 to 62 years, with a mean age of 37 (SD = 10. 8) years; 64.6% of caregivers were daughters of older stroke patients, while 35.4% were daughters-in-law. Majority of daughters (72.6%) were caring for an older mother with stroke, while 27.4% were caring for older fathers. Similarly, among daughters-in-law, 70.6% were caring for mothers-in-law with stroke, whereas 29.4% reported caring for fathers-in-law with stroke. A high percentage of caregivers (70.8%) reported their parents/parents-in-law resided with them, and only 29.2% reported their parents/parents-in-law did not reside with them. Further, close to 50% of the respondents reported the family size ranging from four to six persons.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample population

The number of children reported by caregivers was mostly (67.6%) between 0 and 3, with a mean age of 13.3 years. Table 1 also shows that 78.1% of caregivers were married and 21.9% were single (never married, divorced, or widowed). In terms of education level, slightly more than a third had secondary level education and a third reported having a diploma, while only 8.5% reported not having received any formal education. Majority of caregivers perceived their health status as healthy (52%) or very healthy (36.5%). They were in the prime of health as 44% of the respondents were in the age group of 19-34 years. Further, Table 1 demonstrates that 53.1% of the caregivers rated their economic status as middle, while 34.4% reported their perceived economic status as poor. Majority of (81.2%) the respondents were unemployed.

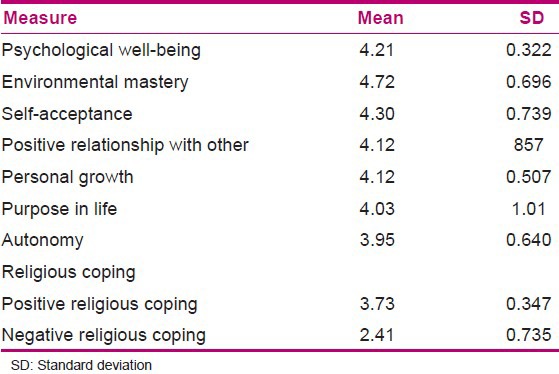

Distribution of the means and standard deviations of psychological well-being and its dimensions and also the religious coping scores among caregivers of stroke patients are illustrated in Table 2. Total mean score of psychological well-being was 4.21 ± 0.322. In addition, it was found that the mean score of environmental mastery was higher (4.72 ± 0.696) and the mean of autonomy score was lower (3.95 ± 0.640) than the other dimensions of psychological well-being. Also, the mean score of positive religious coping scores was higher than the negative religious coping scores (3.73 ± 0.347 vs. 2.41 ± 0.735).

Table 2.

Distribution of the means and standard deviations of religious coping, psychological well-being, and its dimension scores among stroke caregivers

HYPOTHESES TESTING RESULTS

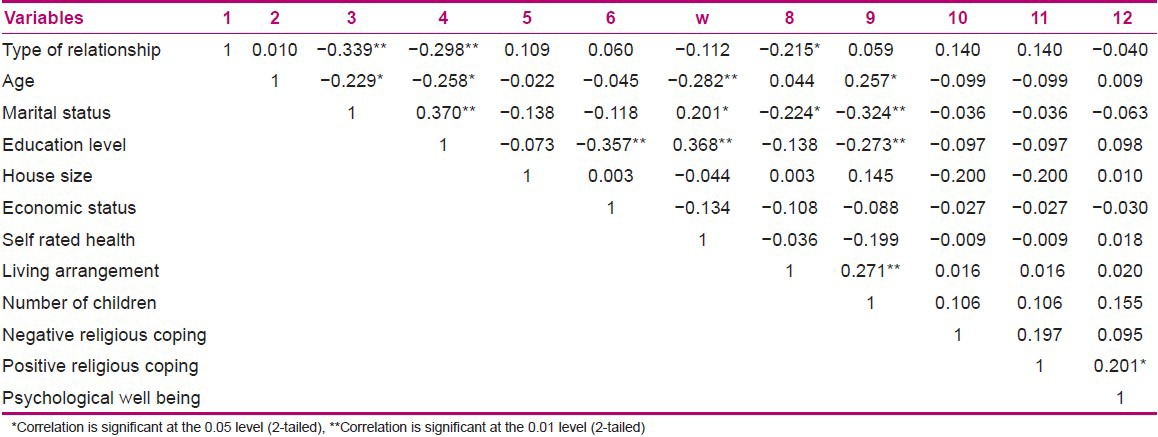

Considering that the presumptions of multiple regression (normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity) are not violated, linear multiple regression analysis was performed to test the first hypothesis of the study. Before performing linear multiple regression analysis, the relationship between caregiver characteristics and psychological well-being was examined on a total sample of 96 caregivers.

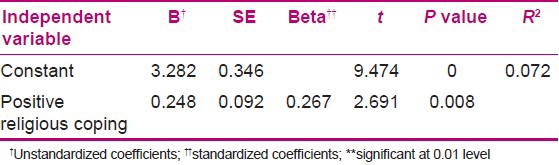

As can be seen from the results of bivariate analyses [Table 3], no differences were found between daughters-in-law and daughter caregivers in terms of psychological well-being, as anticipated. Despite the non-significant difference in psychological well-being between daughters and daughters-in-law caregivers, the mean of psychological well-being in daughters (M = 0.323) was higher than in daughters-in-law caregivers (M = 0.269). In addition, results of this study showed no significant association between caregiver demographic characteristics including age, education, household size, living arrangement prior to stroke, number of children, perceived health, and economic and marital status and their psychological well-being. The only factor that had a significant effect on caregivers’ psychological well-being among all variables was positive religious coping, demonstrating that the carers with a higher score of positive religious coping reported better psychological well-being. Therefore, due to lack of relationship between demographic characteristics and caregivers’ psychological well-being, the demographic variables were not included in future regression analysis. So, the effect of positive religious coping was evaluated using linear regression analysis. Table 4 demonstrates a significant model [ΔF (1, 94) =7.23, P < 0.05] suggesting that 7.2% of changes in psychological well-being can be explained by positive religious coping.

Table 3.

Intercorrelations between caregivers’ demographic variables and psychological well-being at baseline (n=96)

Table 4.

Regression coefficient between psychological well-being and positive religious coping

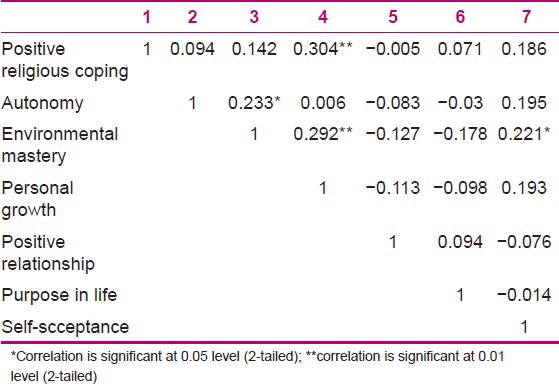

Also, the correlation between positive religious coping and the six dimensions of psychological well-being was evaluated. There was a significant correlation between positive religious coping style and personal growth subscale [r (96) =0.304, P = 003 (two-tailed)] of psychological well-being [Table 5].

Table 5.

Intercorrelations between positive religious coping and psychological well-being dimensions at baseline (n=96)

DISCUSSION

As can be seen from the results, no differences were found between daughters-in-law and daughter caregivers in terms of psychological well-being, as anticipated. The finding is in agreement with Kim's[23] study who demonstrated that the emotional and physical health of daughters-in-law caregivers was not poorer than that of Korean daughter caregivers. However, the mean of psychological well-being in daughters was higher than in daughters-in-law caregivers. Furthermore, type of relationship can be considered as a probable effective characteristic in future studies. In addition, the results of our study showed no significant association between caregiver demographic characteristics and psychological well-being. In this regard, Schulz et al.[24] asserted that demographic variables such as health, age, and income produce an almost small role in improving caregiver burden and depression in the acute period of stroke. Conversely, Choi-Kwon et al.[25] indicated that stroke caregivers who were old, females, daughters-in-law, or less educated were more likely to experience negative emotional health, such as depression and anxiety, and subsequently experience burden. In addition, caregivers who were employed full time were at greater risk for depression.[26] The possible explanation for the inconsistent finding is that the majority of mental health researches had often focused on the association and predicting the ability of caregivers’ characteristics and caregivers’ negative emotional well-being (e.g. on depression and anxiety), while the present study investigated psychological well-being which refers to positive mental health. The positive mental health and mental ill health are two interrelated but generally independent concepts that should be examined on two independent axes.[27]

Further, results of the study showed no significant association between negative religious coping behaviors and caregivers’ psychological well-being. Conversely, Pearce et al.[28] indicated that frequent use of negative religious coping strategies was related to more burden, lower quality of life, and less satisfaction, which also correlated with an increased likelihood of major depressive disorder and anxiety. Similarly, Khanjari et al.,[29] in a study in Iran, found a negative correlation between negative religious coping and caregivers’ spirituality and sense of coherence. The explanation for our findings is that perhaps negative religious coping is more likely to be associated with mental health disorders such as depression than positive mental health, as investigated in the literature. However, findings from the analyses supported the mediating hypothesis for positive religious coping behaviors. The results of regression indicated that 7.2% of the variability in the observed values of psychological well-being is explained by caregivers’ positive religious coping score. Similar results were obtained in a qualitative study of Indian caregivers, who relied strongly on their faith to manage the demands of illness.[30] Also, there was a significant correlation between positive religious coping and personal growth subscale. In this regard, Proffitt et al.[31] reported that use of religion-based coping strategies following a painful life event was expected to facilitate posttraumatic growth, and posttraumatic growth was, in turn, predicted to cause in better present well-being. Mickley et al.[32] emphasized that caregivers who appraised their situation as a portion of God's plan or as a means of gaining strength or understanding from God reported positive outcomes, whereas caregivers who considered their condition as unfair, as an unjust punishment from God, or as rejection from God had low scores on psychological and spiritual health outcomes. A connection with God perhaps affected the individuals’ appraisal of the situation and thereby assisted in perceiving problems positively. It also gave purpose and hopes to individuals, helping them adjust to the difficult events. In this way, the people will most probably use positive thinking when faced with difficulties during caring of their family members. In addition, caregivers who applied religious or spiritual beliefs to adjust with caregiving had a better relationship with care recipients, which was related with lower levels of depression and role immersion.[33] The carers who held the belief that God is behind them in the caring process would not let negative thinks get in the way of care giving. This will trace then a strong caregiver.

Conclusion and implications for practice

The results showed that the use of positive religious coping helped family members to cope with the stress of caring for a relative with severely functional impairments. Positive religious coping more than negative religious coping was a significant determinant of psychological well being. Thus, the role of religious coping in enhancing psychological well being of carers needs to be considered in family intervention programmes. The essential step is that health care professionals must not ignore religious coping as incoherent to their work. Health care professionals should introduce interventions that incorporate religious or spiritual principles to promote caregiving outcome. It is also important to investigate how psychologists could incorporate research findings into their clinical practice.

Limitation

There are some limitations in the current study which need to be considered. The current research was carried out on daughters and daughters-in-law caregiver of stroke survivors with severe disability; hence, this sample was not representative of the wider caregivers’ population. However, further research in a larger samples, more diverse population would add to the body of knowledge on this area. Also, future research should follow a more longitudinal design so as to examine the long-term outcomes of the different forms of religious coping.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the carers of stroke survivors who participated in this study. Thanks are also extended to the neurological wards of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (SUMS) for their cooperation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This work was an unfunded project

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnston SC, Mendis S, Mathers CD. Global variation in stroke burden and mortality: Estimates from monitoring, surveillance, and modelling. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:345–54. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edinburgh: SIGN publication no. 64; 2002. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of patients with stroke. British Association of Stroke Physicians. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson A, Plant H, Moore S, Medina J, Cornwall A, Ream E. Developing supportive care for family members of people with lung cancer: A feasibility study. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:1259–69. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0233-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reinhard SC, Given B, Petlick NH, Bemis A. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. Supporting family caregivers in providing Care. Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakas T, Austin JK, Okonkwo KF, Lewis RR, Chadwick L. Needs, concerns, strategies, and advice of stroke caregivers the first 6 months after discharge. J Neurosci Nurs. 2002;34:242–51. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwood N, Mackenzie A. An exploratory study of anxiety in carers of stroke survivors. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2032–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingersoll-Dayton B, Starrels ME, Dowler D. Caregiving for parents and parents-in-law: Is gender important? Gerontologist. 1996;36:483–91. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer BJ. Gain in the caregiving experience: Where are we? What next? Gerontologist. 1997;37:218–32. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SS. Experience of family caregivers caring for patients. With stroke. Kanhohak-Tamgu. 1994;3:67–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one's physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:946–72. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brody EM. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2004. Women in the middle: Their parent care years. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thune-Boyle IC, Stygall JA, Keshtgar MR, Newman SP. Do religious/spiritual coping strategies affect illness adjustment in patients with cancer? A systematic review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:151–64. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berg-Weger M, Rubio D, Tebb S. Strengths-based practice with family caregivers of the chronically ill: Qualitative insights. Fam Soc. 2001;82:263–72. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenix JB, Cherlin EJ, Prigerson HG, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Kasl SV, Bardley EH. Religiousness and major depression among bereaved family care givers: A 13-month follow-up study. J Palliat Care. 2006;22:286–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papastavrou E, Charalambous A, Tsangari H. Exploring the other side of cancer care: The informal caregiver. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:128–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gall T, Miguez de Renart R, Boonstra B. Religious resources in long-term adjustment to breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2000;18:21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McIntosh DN, Silver RC, Wortman CB. Religion's role in adjustment to a negative life event: Coping with the loss of a child. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:812–21. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.4.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Relig. 1998;37:710–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben-Zur H, Gilbar O, Lev S. Coping with breast cancer: Patient, spouse, and dyad models. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:32–9. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshimoto SM, Ghorbani S, Baer JM, Cheng KW, Banthia R, Malcarne VL, et al. Religious coping and problem-solving by couples faced with prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2006;15:481–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merrill DM. Daughters-in-law as caregivers to the elderly. Res Aging. 1993;15:70–91. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of Psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57:1069–81. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JS. Daughters-in-law in Korean caregiving families. J AdvNurs. 2001;36:399–408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulz R, Tompkins CA, Rau MT. A longitudinal study of the psychosocial impact of stroke on primary support persons. Psychol Aging. 1988;3:131–41. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.3.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi-Kwon S, Kim HS, Kwon SU, Kim JS. Factors affecting the burden on caregivers of stroke survivors in South Korea. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1043–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko JY, Aycock DM, Clark PC. A comparison of working versus nonworking family caregivers of stroke survivors. J Neurosci Nurs. 2007;39:217–25. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200708000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atienza AA, Stephens MA, Townsend AL. Dispositional optimism, role-specific stress, and the well-being of adult daughter caregivers. Res Aging. 2002;24:193–217. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearce MJ, Singer JL, Prigerson HG. Religious coping among caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients. J Health Psychol. 2006;11:743–59. doi: 10.1177/1359105306066629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khanjari S, Oskouie F, Langius-Eklof A. Lower sense of coherence, negative religious coping, and disease severity as indicators of a decrease in quality of life in Iranian family caregivers of relatives with breast cancer during the first 6 months after diagnosis. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35:148–56. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31821f1dda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehrotra S, Sukumar P. Sources of strength perceived by females caring for relatives diagnosed with cancer: An exploratory study from India. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:1357–66. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Proffitt D, Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. Judeo-Christian clergy and personal crisis: Religion, posttraumatic growth and well being. J Religion Health. 2007;46:219–31. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mickley JR, Pargament KI, Brant CR, Hipp KM. God and the search for meaning among hospice caregivers. Hosp J. 1998;13:1–17. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1998.11882904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang BH, Noonan AE, Tennstedt SL. The role of religion/spirituality in coping with caregiving for disabled elders. Gerontologist. 1998;38:463–70. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]