Abstract

Background

Allergy diagnosis by determination of allergen-specific IgE is complicated by clinically irrelevant IgE, of which the most prominent example is IgE against cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCDs) that occur on allergens from plants and insects. Therefore, CCDs cause numerous false-positive results. Inhibition of CCDs has been proposed as a remedy, but has not yet found its way into the routine diagnostic laboratory. We sought to provide a simple and affordable procedure to overcome the CCD problem.

Methods

Serum samples from allergic patients were analysed for allergen-specific IgEs by different commercial tests (from Mediwiss, Phadia and Siemens) with and without a semisynthetic CCD blocker with minimized potential for nonspecific interactions that was prepared from purified bromelain glycopeptides and human serum albumin.

Results

Twenty two per cent of about 6000 serum samples reacted with CCD reporter proteins. The incidence of anti-CCD IgE reached 35% in the teenage group. In patients with anti-CCD IgE, application of the CCD blocker led to a clear reduction in read-out values, often below the threshold level. A much better correlation between laboratory results and anamnesis and skin tests was achieved in many cases. The CCD blocker did not affect test results where CCDs were not involved.

Conclusion

Eliminating the effect of IgEs directed against CCDs by inhibition leads to a significant reduction in false-positive in vitro test results without lowering sensitivity towards relevant sensitizations. Application of the CCD blocker may be worthwhile wherever natural allergen extracts or components are used.

Keywords: allergens and epitopes, CCDs, cross-reactive carbohydrates, false positives, IgE

The purpose of determining specific IgE (sIgE) in serum-based allergy diagnosis is assigning the allergen(s) that cause(s) notable allergic symptoms. This attractively simple principle is, however, perturbed by the occurrence of clinically insignificant IgEs 1. A number of candidates for these interfering IgEs have been identified and classified into IgEs that bind to peptide epitopes and IgEs that bind to carbohydrate epitopes 1. Weighting of these different reasons has never been made. The extraordinarily wide distribution of a particular carbohydrate epitope was addressed three decades ago, when the now well-known term ‘cross-reactive carbohydrate determinant’ (CCD) was coined 2. The structural basis of CCDs is complex-type Asn-linked oligosaccharides on glycoproteins 3,4. In particular, it is the presence of core-α1,3-linked fucose that implants the same epitope onto glycoproteins from insect venoms, plant pollens, vegetable foodstuffs and even latex 5–9. Consequently, a patient who develops IgE against CCDs on whichever allergen reacts with other allergens that contain typical plant or insect glycosylation. Up to a quarter of all patients undergoing sIgE testing show these multiple reactions 1,8,10–12. The problem is that anti-CCD IgE, from what we know today, has no clinical significance 1,11,13–18. The picture was further complicated around 2001 as multivalent CCD-containing proteins displayed relevant biological potency in in vitro histamine release tests 12,19,20. Since then, no patient has been presented who reacted against CCDs in a way clearly addressable as an allergic reaction. Thus, it appears prudent to adhere to the notion that anti-CCD IgE has no clinical significance. While we can only speculate about the reasons for this remarkable circumstance 4, the serious consequence is that for a large cohort of patients, any sIgE test will return a positive result, which will, however, be false positive for most or all of the allergens. The severity of the problem may have been underestimated in single allergen testing, where only small numbers of allergens carefully selected on the basis of anamnesis are tested, for example, with the ImmunoCAP system. Positive results are expected, and false positives escape notice as they do not raise suspicion. By contrast, array tests return a multitude of positive results for CCD-positive patients. The problem has been known for several years, and more or less promising solutions have been suggested. Some laboratories determine anti-CCD IgE with a MUXF-CAP (Thermo Scientific/Phadia; ‘MUXF’ is explained in Fig. 2). This identifies problematic results, but cannot help to discriminate false from truly positive results. Removal of anti-CCD IgE with immobilized CCDs has also been suggested 15, but dismissed as too laborious for routine application 21. The German guideline on allergy diagnosis 14 as well as newer literature 22 mentions inhibition of anti-CCD IgE but does not state how the inhibition should be achieved. A mixture of natural plant glycoproteins to be used for CCD inhibition is available from Mediwiss Analytics (Moers, Germany). Natural glycoproteins could contain peptide epitopes that cause unwanted inhibitions. For many years, our group has used a semisynthetic CCD blocker consisting of bromelain glycopeptides coupled to bovine serum albumin (BSA) 20,23,24. The proteolytic digestion of the starting material ensures the destruction of peptide epitopes. However, only rudimentary glycopeptide purification has been performed and BSA may itself bind IgE in patients who are allergic to meat or milk.

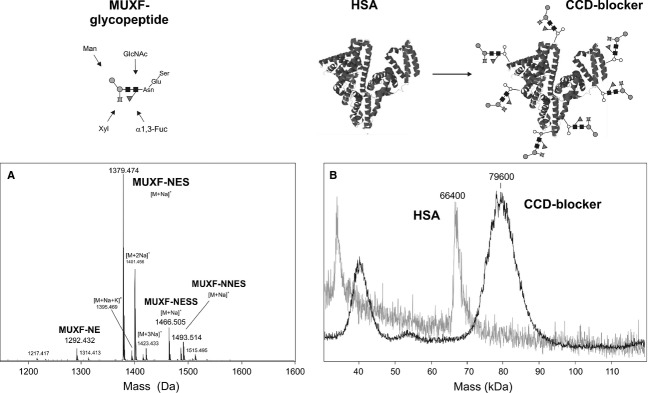

Figure 2.

Preparation of the CCD blocker. Highly purified glycopeptides containing core α1,3-fucose and xylose are chemically coupled to human serum albumin (HSA). The glycopeptides contain 2-4 amino acids at maximum, which is verified by MALDI-TOF MS (panel A). The glycopeptide–protein conjugate is analysed by MALDI-TOF MS (panel B). The valency of the CCD blocker can be estimated as being around 8–9 from the mass difference of conjugate and native HSA. The glycan structure abbreviation ‘MUXF’ is based on the proglycan system (www.proglycan.com). Information on the availability of this CCD blocker can be found on the proglycan home page.

In the present work, we used a new, highly pure and specific version of our CCD blocker to determine sIgEs in single allergen tests as well as on multi-allergen strips and component arrays. For several patients, laboratory diagnosis was augmented by skin prick tests.

Methods

Patients

In 2012, ‘Das Labor’, a medical laboratory in Villach (Austria), examined 6220 serum samples with suspected sensitizations to pollens, foods or insect venoms. All sera were tested using customized allergy test strips (Mediwiss, Moers) that contained indicators for CCD. All tests were also performed with a CCD blocker. Several sera were additionally tested for selected allergen extracts or components using other test methods.

Preparation of the semisynthetic CCD blocker

The CCD blocker was prepared from pineapple stem bromelain and human serum albumin (HSA) as follows: bromelain (Sigma-Aldrich, Vienna, Austria) was purified by cation-exchange chromatography, lyophilized and digested with pronase (Sigma-Aldrich) 8. The digest was subjected to gel filtration on Sephadex G25 (GE Healthcare, Vienna, Austria), and orcinol-positive fractions were lyophilized. After a second digestion with pronase, the glycopeptides were passed over Sephadex G50 (GE Healthcare). Success of the proteolytic digestion was checked by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) on an Autoflex instrument (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) with 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid as the matrix. The glycopeptide pool was filtered through a 10-kDa cut-off membrane (Millipore-Amicon, Vienna, Austria) to remove residual protease. A multivalent neoglycoprotein was obtained by reacting the glycopeptide fraction with dinitro-difluorobenzene (VWR, Darmstadt, Germany). The activated glycopeptide was reacted with HSA (catalogue no. 12668, VWR Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) overnight at room temperature. The conjugate was recovered by passage over Biogel P30 (Bio-Rad, Vienna, Austria). Its quality was verified by linear MALDI-TOF MS with sinapinic acid.

This inhibitor is equivalent with the CCD blocker described in www.proglycan.com.

Evaluation of optimal CCD blocker concentration and incubation time

In the university laboratory, sIgEs were determined by ELISA. Briefly, ascorbate oxidase (5 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) in ammonium carbonate of pH 9.6 was used as the CCD-containing antigen. Wells were blocked with BSA in Tris buffer of pH 7.2 containing 0.05% Tween 20. CCD blocker and sera were diluted with the same buffer. The second antibody was mouse anti-human IgE conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (PD Pharmingen, Schwechat, Austria) diluted 1: 500. Antibody incubations were conducted for 1 h at 37°C.

Custom-made AllergyScreen™ strips were obtained from Mediwiss Analytic (Moers). The strip for inhalant allergens contained three additional slots with bromelain, horseradish peroxidase and ascorbate oxidase in addition to extracts from various pollens. The food allergen strip contained a mixture of the above-listed three glycoproteins in a single slot. ImmunoCAP (Fisher Scientific/Phadia, Vienna, Austria) was performed with natural allergens or allergen components as indicated in the Results section. Selected sera were subjected to the 103-component ImmunoCAP ISAC (Fisher Scientific/Phadia). Other sera were tested with the Immulite 2000, 3gAllergy Specific IgE Universal Kit (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). All tests were applied according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Inhibition of anti-CCD IgE

Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants inhibitions were performed by adding 10 μl of the CCD blocker to 500 μl serum, resulting in a final concentration of 20 μg/ml. After thorough mixing, sera were processed immediately. A few inhibited sera were stored at 4°C for 2 weeks with no notable reduction in the inhibitory efficacy.

Results

Revisiting the magnitude of the CCD problem

A notable 22% of sera samples from 6220 patients tested in a routine diagnostic laboratory with custom-made Mediwiss multi-allergen strips containing indicators for CCD reacted with the CCD controls bromelain, HRP and ascorbic oxidase. The multi-allergen panels indicated that most patients seemingly had a broad sensitization against all types of pollens, cockroach (the only insect on the strips used) and all types of vegetable food. (Note that latex and insect venoms were not included on these strips.) Particularly, high values were often obtained for ragweed pollen, rye and celery. The unacceptable consequence was that for every fourth patient, the sIgE-based diagnosis delivered meaningless results. The test strip format did, however, at no extra cost expose the CCD problem, which may have remained concealed if only a few single allergens had been tested. Remarkably, the severity of the reactions fell mainly into RAST class II or higher (Fig. 1), but it should be noted that the MW strip test tends to give higher readings for CCD-based sIgE values than the CAP test.

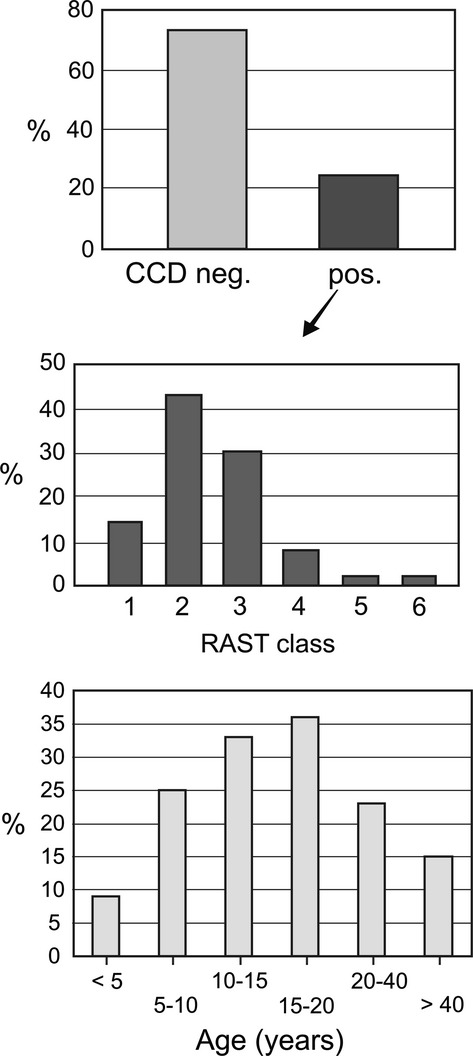

Figure 1.

Incidence of anti-cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) IgE. Panel A shows the percentage of CCD nonreactive and CCD-positive sera from a panel of 6220 patients. Panel B shows the RAST classes of CCD sensitization as measured with the Mediwiss test. Panel C stratifies the CCD reactivity according to patients’ age.

The incidence of CCD reactivity was highly age dependent (Fig. 1). Anti-CCD IgE appears at early school age and peaks in the later teenage years for which a 36% incidence was observed among 563 samples (Fig. 1). Thus, the risk of CCD-based misdiagnosis is highest at and around the teenage years – an age at which many patients experience their first visit to an allergologist.

Preparation and characterization of the CCD blocker

Our aim was to prepare a highly defined neoglycoprotein that would not cause any interference with IgE–allergen interactions other than those based on CCDs. Natural plant or insect glycoproteins may themselves contain unwanted peptidic epitopes, or they may contain impurities with such epitopes. Therefore, the protein backbone was first destroyed by proteolytic digestion. Pineapple stem bromelain was chosen as the source of glycopeptide as it is homogeneous both with regard to protein backbone and carbohydrate structure. The bromelain glycopeptides were then thoroughly purified by various means to arrive at a chemically defined composition, which was verified by mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) and amino acid analysis (Fig. 2). The preparation contained di- to tripeptides, which are assumed too small to harbour peptidic epitopes. As multivalency of glycan epitopes is considered important for strong binding 25,26, the glycopeptides were coupled to an immunologically inert carrier protein. The incorporation rate was verified by SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF MS (Fig. 2), which indicated an average content of 8–10 glycopeptides per HSA molecule. In fact, a study with rabbit anti-HRP serum revealed a more than tenfold increase in inhibitory potency for a multivalent BSA neoglycoconjugate compared with monomeric glycopeptide, despite an equal concentration of GlcNAc [I. Weismann (now Dalik), F. Altmann, unpublished data].

The glycopeptide–HSA conjugate, termed CCD blocker, was then tested for its potency as an inhibitor in an ELISA format using ascorbate oxidase as a coat antigen and a patients’ serum pool. Substantial inhibition could be observed at 5 μg/ml (Fig. 3), which was the concentration used in previous work with a similar inhibitor preparation 24. To ensure method robustness, 20 μg/ml was chosen as the standard concentration for further experiments. This translates into approximately 5 μmol/l in terms of GlcNAc with ten glycopeptides per protein molecule and two GlcNAc residues per glycan.

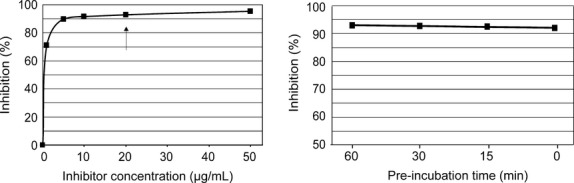

Figure 3.

Concentration and time dependency of the inhibitory effect of the Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) blocker. ELISA experiments were conducted with an undiluted pool of 5 human CCD-positive sera. The coat antigen was ascorbate oxidase. The arrow indicates the concentration recommended for routine applications. The left panel shows the inhibition percentage in relation to inhibitor concentration (with 15-min pre-incubation). The right panel shows the effect of pre-incubation of serum with inhibitor (at room temperature with 20 μg/ml CCD blocker).

Specific inhibitions are usually carried out with long pre-incubation periods, for example, 1 h at 37°C 5 or overnight at 4°C 27. This somewhat collides with the time scale of formation of an antibody-ligand equilibrium, which is in the seconds range. Therefore, we measured the effectiveness of inhibition after different pre-incubation times (at room temperature) (Fig. 3).

First experiences with CCD inhibition

The use of multi-allergen test strips with CCD controls clearly exposed the CCD problem and prompted us to find a remedy. Thus, all sera that tested positive for CCDs by Mediwiss test strips in 2012 were analysed in parallel with and without CCD blocker. First results immediately pointed at the potential of this approach as exemplified by four cases selected from the cases where CCD inhibition was performed.

Case 1: a 16-year-old patient (f16) with symptoms that indicated a mite, but not a pollen or even less likely any food allergy. The serum tested positive for the whole range of CCD-containing allergens from pollens to foods and showed an only moderate reaction towards mites (Fig. 4). Conducting the serum incubation in the presence of CCD blocker abolished all reactions except that with mite extracts (Fig. 4). While revealing the mite sensitization of this patient, this result also demonstrated that mites, although arthropods, were not affected by the CCD problem 28.

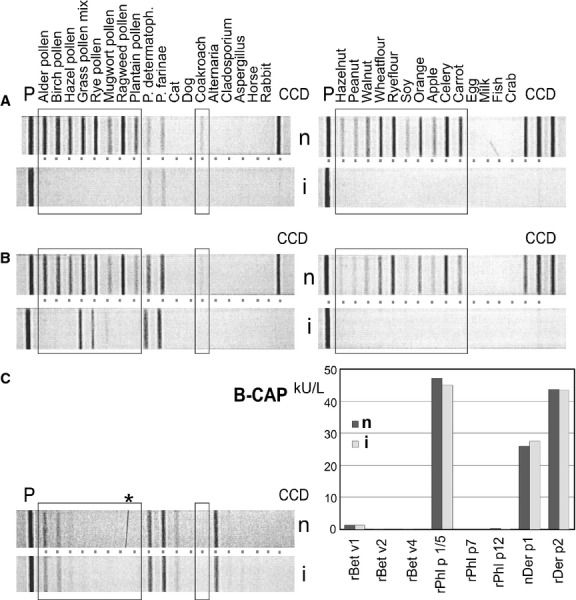

Figure 4.

Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) inhibition as observed on multi-allergen test strips. Custom-made test strips with CCD markers were incubated with serum in the absence (n) or presence (i) of inhibitor (20 μg/ml). The boxes mark allergens that may exhibit CCD-based IgE binding. Sera A, B and C were obtained from patients f16, m19 and f12 (a CCD-negative patient). The * denotes a mechanical scratch in panel C. The results of CAP tests performed with serum B (insert B-CAP) show that CCD inhibition does not affect exclusively protein-based reactions with allergen components.

Case 2: a 19-year-old patient (m19) who suffered from hay fever throughout the year with seasonal peaks. The test strip first indicated that he had a very broad sensitization (Fig. 4). Upon inhibition, the reactions towards all tree pollens, ragweed, cockroach and all foods vanished. These results were later corroborated by CAP tests (Fig. 4). It is noteworthy that the binding pattern did not change when inhibition was performed with the serum of a patient of 16 years, who was not reactive to CCDs (Fig. 4).

Two more cases (3 and 4) from the hundreds of similar cases are presented here as these patients had also been subjected to skin testing (Table 1). Obviously, CCD blocking generally led to a drastic simplification of the results for CCD-positive patients.

Table 1.

Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) inhibition in comparison with skin testing. The sera were tested with a Mediwiss multi-allergen strip for inhalative allergens that additionally contained a CCD marker lane. D. pteron. stands for Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (house dust mite). MW n and MW I denote values (in U/ml) obtained with the normal procedure and with inhibition, respectively

| Patient | w70 | w24 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | MW n | MW i | SPT | MW n | MW i | SPT |

| Alder | 16.5 | 0 | neg | 3.6 | 0 | neg |

| Birch | 30.5 | 0 | neg | 5.8 | 0 | neg |

| Hazel | 26.9 | 0 | neg | 6.5 | 0 | neg |

| Grass mix | 23.8 | 0 | neg | 28 | 19.7 | pos |

| Rye | 53.4 | 0.2 | neg | >100 | 9.4 | pos |

| Mugwort | 7.2 | 0 | neg | 2.2 | 0 | neg |

| Ragweed | >100 | 0.2 | neg | 23 | 0 | neg |

| Plantain | 13.9 | 0 | neg | 5.1 | 0 | neg |

| D. pteron. | 0 | 0 | neg | 0 | 0 | neg |

| D. farinae | 0 | 0 | neg | 0 | 0 | neg |

| Cat | 0 | 0 | neg | 0 | 0 | n.d. |

| Dog | 0 | 0 | n.d. | 0 | 0 | n.d. |

| Cockroach | 10.2 | 0 | n.d. | 2 | 0 | neg |

| Alternaria t. | 0 | 0 | neg | 0 | 0 | neg |

| Cladosp. h. | 0 | 0 | neg | 0 | 0 | neg |

| Aspergillus f. | 0 | 0 | neg | 0 | 0 | neg |

| Horse | 0 | 0 | n.d. | 0 | 0 | neg |

| Rabbit | 0 | 0 | n.d. | 0 | 0 | neg |

| CCD mix | 26.1 | 0 | 4.5 | 0 | ||

| Hazelnut | 3.4 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Peanut | 1.7 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Walnut | 6.4 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Wheat flour | 42.3 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Rye flour | 73.1 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Soy | 1.4 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Orange | 4 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Apple | 1.8 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Celery | 27.1 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Carrot | 14.3 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Chicken egg | 0 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Milk protein | 0 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Cod | 0 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Crab/shrimp | 0 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Bromelain | 38.4 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| HRP | 9.3 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| Asc-oxidase | 30.4 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

neg, negative; pos, positive; n.d.,not detected.

Detailed case studies comparing Mediwiss allergy test strips with Phadia ImmunoCAP and ISAC

The results described above were encouraging, but we considered it advisable to verify their reliability by other test methods. Therefore, additional in vitro tests with the ImmunoCAP and ISAC systems were performed with a few patients. Some were also skin prick tested.

Case 5: a 46-year-old man (m46) who had a suspected insect venom allergy but no other clearly perceptible allergy symptoms. The two multi-allergen strips showed a large number of positive values indicating substantial polysensitization (Table 2). As these were custom-designed strips with CCD markers, they revealed this serum to be reactive to CCDs. None of the allergens showed a positive reaction when the tests for inhalative and food allergens were conducted with the CCD blocker (Table 2). This astounding outcome was verified with CAP tests ± inhibition of CCDs, which gave two noteworthy results. First, the IgE values measured with CAP were generally much lower than those obtained with Mediwiss strips. Second, upon inhibition, CAP values fell drastically, albeit not in all cases to below the 0.35 kU/l cut-off value. A component-resolved analysis with ISAC indicated that the remaining low reactivities with grass and ragweed pollens should still be seen as false positives. Therefore, although the CCD blocker performed suboptimally in the CAP format, it did turn five strong positives into three negative and two weakly positive reactions.

Table 2.

Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) inhibition in different test formats. The Mediwiss strip test (MW), the classical ImmunoCAP system and the ImmunoCAP ISAC allergen array were used to measure specific IgE against selected allergens without (n) and with (i) CCD blocker. The evaluation row ‘Eval’ shows ‘o.k.’ for supposedly correct inhibition below the 0.35 U/ml threshold. ‘+o.k.’ denotes values that had remained correctly positive despite CCD inhibition. ‘ins’ denotes insufficient inhibition, and ‘unex’ marks unexpected reduction in readings in case of supposedly CCD-free allergen. More examples are shown in Table S1

| m46 Allergen source | MW n U/ml | MW i U/ml | Eval | CAP n U/ml | CAP i U/ml | Eval | Component | ISAC n ISU-E | ISAC i ISU-E | Eval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alder pollen | 44.1 | 0 | o.k. | |||||||

| Birch pollen | >100 | 0 | o.k. | 19.6 | 0.11 | o.k. | rBet v 1/2/4 | 0/0/0 | 0/0/0 | |

| Hazel pollen | >100 | 0.23 | o.k. | |||||||

| Grass pollen mix | 99.7 | 0 | o.k. | 25.0 | 1.11 | ins | rPhl p1/2/5/6/7/11/12 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0 | 0/0/0/0/0/0/0 | |

| Rye pollen | >100 | 0 | o.k. | nPhl p4*/nCyn d 1* | 10/26 | 0/0 | o.k | |||

| Mugwort pollen | 14.9 | 0 | o.k. | 21.6 | 0.21 | o.k | nArt v1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ragweed pollen | >100 | 0 | o.k. | 25.7 | 0.49 | ins | nAmb a1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Plantain pollen | 32.9 | 0 | o.k. | rPla l 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Mite (D. pteronyssinus) | 0.59 | 0 | rDer p 1/nDer p2 | 0/0 | 0/0 | |||||

| Mite (D. farinae) | 0.48 | 0 | ||||||||

| Cockroach | 13.6 | 0 | o.k. | rBla g 1/2/5/7 | 0/0/0/0 | 0/0/0/0 | ||||

| Cat | 0 | 0 | rFel d 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Dog | 0.37 | 0 | unex | rCan f 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Hazelnut | 3.4 | 0 | o.k. | 17.4 | 0.08 | o.k | rCor a 1/8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Peanut | 1.7 | 0 | o.k. | rAra h 1/2/3/8/9 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Walnut | 6.4 | 0 | o.k. | nJug r 1/2*/3 | 0/10/0 | 0/0/0 | o.k. | |||

| Wheat flour | 42.3 | 0 | o.k. | rTri a 14/19 | 0/0 | 0/0 | ||||

| Rye flour | 73.1 | 0 | o.k. | |||||||

| Soy | 1.4 | 0 | o.k. | rGly m 4/nGly m 5/6 | 0/0/0 | 0/0/0 | ||||

| Apple | 1.8 | 0 | o.k. | rPru p 1/3 | 0/0 | 0/0 | ||||

| Celery | 27.1 | 0 | o.k. | rApi g 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Bee venom | 28.5 | 1.1 | (o.k.) | |||||||

| Component: rApi m1 | 1.63 | 0.31 | ?a | rApi m1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Yellow jacket venom | 28.5 | 18.3 | +o.k. | rPol d5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | +o.k | |||

| Component: rVes v 1/5 | 11.8/48.7 | 9.7/44.6 | +o.k. | rVesv5 | 6.2 | 8.9 | +o.k | |||

| CCD mix | >100 | 0 | o.k. | CCD MUXF3 | 20 | 0 | o.k. | |||

| CCD bromelain | 38.4 | 0 | o.k. | nCry j 1* | 9.3 | 0 | o.k. | |||

| CCD HR-peroxidase | 9.3 | 0 | o.k. | nCup a 1* | 11 | 0 | o.k. | |||

| CCD Asc-oxidase | 30.4 | 0 | o.k. | nOle e 1* | 4.5 | 0 | o.k. | |||

| nPla a 1* | 12 | 0 | o.k. |

Conflict between positive CAP and negative ISAC of Api m1.

Natural components, most probably with CCD-type glycosylation.

Discrimination between bee and yellow jacket sensitization is a particularly difficult task in the case of CCD-reactive sera 24,29. Serum from m46 gave strong reactions with both bee and wasp venom, indicating double sensitization (Table 2). With CCD inhibition, the values differed substantially, which would have allowed a choice of the allergen for specific immunotherapy. While a further reduction in the bee venom value – again compared with ISAC results – might be desirable, a certain protein-based cross-reactivity cannot be excluded. The reaction with the recombinant components Ves v 1 and Ves v 5 in the CAP test was not affected by the CCD inhibitor apart from incidental error.

Analysis of serum from m46 by the multicomponent array ISAC largely corroborated the results obtained with Mediwiss test strips with the CCD blocker. However, two components (nCyn d 1, nJug r 2) exhibited strong reactions. These allergens are natural glycoproteins containing CCDs. The same applies for nCry j 1, nCup a 1, nOle e 1 and nPla a 1, which all showed strong reactions with this serum. In line with the findings for other test systems, CCD inhibition totally abolished all these presumed false-positive values (Table 2).

Case 6: a 4-year-old boy (m4) with presumed food allergy. Again, the serum tested positive with the whole panel of CCD-containing allergens (Table S1). Again, all readings turned negative in the test strip format, with the exception of house dust mite and cat, which do not contain CCDs. Accordingly, ISAC testing showed sensitization against Der p 1 and Fel d 1. While m4 did not react to food extracts or components, he presented with a moderate sensitization towards mites and cat. It is noteworthy that CAP and ISAC additionally revealed a grass pollen sensitization that was not detected by the CCD-blocked Mediwiss test. Even with CAP, grass pollen extract gave a borderline reading. While this may argue against the use of the CCD blocker, we rather assume the highly varying content of Phl p 1 in allergen extracts as being the reason for this discrepancy 30. With this in mind, the balance for CCD inhibition with CAP tests for this patient is one correctly identified as positive versus five sera now correctly rated as negative. In the ISAC, several false-positive values of natural components were corrected by CCD inhibition.

Case 7: a 12-year-old boy (m12) who gave many positive reactions, of which only grasses, mugwort, mites, cat and dog remained positive in the strip test as well as with CAP single allergen testing (Table S1). Remarkably, the components rCan f 1, rCan f 2, rCan f 3 and nCan f 5 did not react, which points at a discrepancy outside the CCD problem.

CCD inhibition with the Immulite 2000

A separate group of patients was diagnosed using the 3gAllergy Specific IgE assay system from Siemens. Several sera, for which CCD reactivity was detected using the Mediwiss strip test, were re-analysed in the absence and presence of CCD inhibitor. The three examples show that the CDD problem occurs in the Siemens test just as with the Mediwiss strips (Table S2) – albeit with lower readings (similar as found for the ImmunoCAP test). CCD inhibition abolished several positive readings essentially the same way as on the test strips indicating that this approach leads to simpler and more accurate diagnostic results also with this fourth system tested.

Discussion

Inhibition of anti-CCD IgG and IgE has been practised for a while in basic research 5,20,23,24. Only recently have collaborative efforts been undertaken to use this strategy to clarify questionable sIgE results of apparently honeybee/wasp double-positive patients. In particular, the Janus-headed role of the glycoprotein hyaluronidase could be defined by CCD inhibition in IgE immunoblots 24,29. Neither our semisynthetic CCD blocker nor the improved version we present here has hitherto been used in routine sIgE-based allergy diagnostics. The need to enter this field emerged from the use of multi-allergen screening strips, which accrued an enormous number of positive results irreconcilable with patients’ histories (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

The perfect CCD inhibitor fully suppresses all carbohydrate-based IgE reactivity. In practice, that means suppression under the cut-off level of 0.35 kU/k. Furthermore, the perfect CCD inhibitor neither dilutes the sample nor brings about unwanted inhibition of non-CCD interactions by virtue of nonhuman proteins being potentially cross-reactive with true allergens. Especially, the second point argues against the use of natural glycoproteins or mixtures thereof, as recently suggested by H. Malandain (Oral presentation at XXVIII Congress of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2009, Warsaw). The CCD blocker we describe here appears to essentially meet all three requirements. It must be admitted that readings were not pushed below the 0.35 kU/l level in all cases. This deficiency was mainly observed with CAP tests and never with the ISAC system. It may result from a higher antigen density in the CAP matrix, as the multivalency effect bears for the immobilized ligand just as much as for the soluble CCD blocker. This is exemplified by ELISA experiments, where the extremely densely glycosylated HRP required somewhat higher inhibitor concentrations than ascorbate oxidase (data not shown). Such incomplete inhibition may be overcome by increasing the inhibitor concentration, or it may require use of other glycan structures. This should be investigated in future research. The incomplete inhibition may, however, be caused by protein-specific IgE and thus constitute a truly positive value, which could explain patient m4′s CAP values for rye pollen or patient m12′s for wheat flour (Table 2).

Discrimination between honeybee and yellow jacket sensitization, where CCD-positive patients regularly appear as double sensitized, is a special case 24,29. As seen from patient m46′s CAP results and other, undisclosed, data, CCD inhibition does not necessarily lead to all or nothing situation, due in particular to insufficient inhibition of the reactivity against honeybee venom. A decision as to which allergen should be chosen for specific immune therapy could nevertheless be readily made on the basis of patient m46′s results with the CCD blocker (Table 2).

While pointing out shortcomings of the CCD blocker in this study, we should not ignore problems associated with the standard sIgE determinations applied here. One glaring example is the positive value of Api m1 for patient m46, which can hardly be interpreted as anything else but an outlier – a regrettable consequence of sIgE analyses (usually) not being performed in duplicate. Another example is the apparent shortage of Phl p 1 on Mediwiss strips leading to false-negative results, as seen with patient m4 (case 6). Generally, the quantitative values obtained with the different test systems have to be taken with a strikingly large grain of salt.

The clear conclusion that can be drawn from these experiments is that application of the semisynthetic CCD blocker rendered the results drastically simpler and more realistic for all patients presenting with anti-CCD IgE. As repeatedly shown, CCD reactivity affects about a quarter of all patients 8,11,20. The present study additionally points to an age dependence for the development of anti-CCD IgE. While rare among younger children, anti-CCD IgE becomes increasingly visible up to the end of the teenage years. This may support two perceptions. First, anti-CCD IgE is the result of a regular sensitization process rather than part of the natural antibody ensemble. Second, the childhood onset of the incidence curve argues against a general connection between CCD positivity and abuse, as found for patients of a clinic with a focus on alcohol withdrawal syndrome 13,31. The fact is that every third patient in teenage and early adult years is affected by the CCD problem, and hence, in vitro testing yields pointless results for allergen extracts and many natural components, irrespective of the test system used. CCD inhibition, for example, with the semisynthetic CCD blocker, appears to be a technically simple and effective remedy.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this work were financed by the Austrian Wirtschaftsservice. We are grateful to Peter Forstenlechner, MSc., from Thermo Scientific Austria for generous help with CAP and ISAC testing. We gratefully acknowledge text editing by Elise Langdon-Neuner.

Author contributions

FH performed Mediwiss tests, ES, WF, SS and WH performed diverse other immune tests, TD prepared the CCD blocker, and FA coordinated work and prepared the manuscript. All authors assisted in discussions and manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of interest

The organization employing TD and FA holds IP rights on the CCD blocker described in this study.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) inhibition in different test formats – additional cases.

Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) inhibition using the Siemens Immulite 2000 with 3gAllergy Specific IgE Universal Kit.

Reference

- Ebo DG, Hagendorens MM, Bridts CH, De Clerck LS, Stevens WJ. Sensitization to cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants and the ubiquitous protein profilin: mimickers of allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aalberse RC, Koshte V, Clemens JG. Immunoglobulin E antibodies that crossreact with vegetable foods, pollen, and Hymenoptera venom. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1981;68:356–364. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(81)90133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commins SP, Platts-Mills TA. Allergenicity of carbohydrates and their role in anaphylactic events. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2010;10:29–33. doi: 10.1007/s11882-009-0079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann F. The role of protein glycosylation in allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2007;142:99–115. doi: 10.1159/000096114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencurova M, Hemmer W, Focke-Tejkl M, Wilson IB, Altmann F. Specificity of IgG and IgE antibodies against plant and insect glycoprotein glycans determined with artificial glycoforms of human transferrin. Glycobiology. 2004;14:457–466. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubelka V, Altmann F, Staudacher E, Tretter V, Marz L, Hard K, et al. Primary structures of the N-linked carbohydrate chains from honeybee venom phospholipase A2. Eur J Biochem. 1993;213:1193–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaka A, Yano A, Itoh N, Kuroda Y, Nakagawa T, Kawasaki T. The structure of a neural specific carbohydrate epitope of horseradish peroxidase recognized by anti-horseradish peroxidase antiserum. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4168–4172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretter V, Altmann F, Kubelka V, Marz L, Becker WM. Fucose alpha 1,3-linked to the core region of glycoprotein N-glycans creates an important epitope for IgE from honeybee venom allergic individuals. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1993;102:259–266. doi: 10.1159/000236534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IB, Zeleny R, Kolarich D, Staudacher E, Stroop CJ, Kamerling JP, et al. Analysis of Asn-linked glycans from vegetable foodstuffs: widespread occurrence of Lewis a, core alpha1,3-linked fucose and xylose substitutions. Glycobiology. 2001;11:261–274. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.4.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller UR, Johansen N, Petersen AB, Fromberg-Nielsen J, Haeberli G. Hymenoptera venom allergy: analysis of double positivity to honey bee and Vespula venom by estimation of IgE antibodies to species-specific major allergens Api m1 and Ves v5. Allergy. 2009;64:543–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari A. IgE to cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants: analysis of the distribution and appraisal of the in vivo and in vitro reactivity. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;129:286–295. doi: 10.1159/000067591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal S, Kolarich D, Foetisch K, Lauer I, Altmann F, Conti A, et al. Molecular characterization and allergenic activity of Lyc e 2 (beta-fructofuranosidase), a glycosylated allergen of tomato. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:1327–1337. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Quintela A, Valcarcel C, Campos J, Alonso M, Sanz ML, Vidal C. Biologic activity of cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants in heavy drinkers. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:759–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jappe U, Raulf-Heimsoth M. The significance of cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) for allergy diagnosis. Allergologie. 2008;31:82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Malandain H, Giroux F, Cano Y. The influence of carbohydrate structures present in common allergen sources on specific IgE results. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;39:216–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari A, Ooievaar-de HP, Scala E, Giani M, Pirrotta L, Zuidmeer L, et al. Evaluation by double-blind placebo-controlled oral challenge of the clinical relevance of IgE antibodies against plant glycans. Allergy. 2008;63:891–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens M, Amler S, Moerschbacher BM, Brehler R. Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants strongly affect the results of the basophil activation test in hymenoptera-venom allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:1333–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Veen MJ, van Ree R, Aalberse RC, Akkerdaas J, Koppelman SJ, Jansen HM, et al. Poor biologic activity of cross-reactive IgE directed to carbohydrate determinants of glycoproteins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacovacci P, Afferni C, Butteroni C, Pironi L, Puggioni EM, Orlandi A, et al. Comparison between the native glycosylated and the recombinant Cup a1 allergen: role of carbohydrates in the histamine release from basophils. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:1620–1627. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foetisch K, Westphal S, Lauer I, Retzek M, Altmann F, Kolarich D, et al. Biological activity of IgE specific for cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:889–896. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Nitsch S, Hemmer W, Altmann F. Improving allergy diagnosis by removal of CCD-specific IgE from patients′ sera. Allergy. 2009;64(Suppl. 90):30. [Google Scholar]

- Jappe U, Petersen A, Raulf-Heimsoth M. Immediate-type allergic reactions and cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) Allergo J. 2013;22:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IB, Harthill JE, Mullin NP, Ashford DA, Altmann F. Core alpha1,3-fucose is a key part of the epitope recognized by antibodies reacting against plant N-linked oligosaccharides and is present in a wide variety of plant extracts. Glycobiology. 1998;8:651–661. doi: 10.1093/glycob/8.7.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Focke M, Leonard R, Jarisch R, Altmann F, Hemmer W. Reassessing the role of hyaluronidase in yellow jacket venom allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:184–190. e181. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecioni S, Faure S, Darbost U, Bonnamour I, Parrot-Lopez H, Roy O, et al. Selectivity among two lectins: probing the effect of topology, multivalency and flexibility of “clicked” multivalent glycoclusters. Chemistry. 2011;17:2146–2159. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dam TK, Brewer CF. Effects of clustered epitopes in multivalent ligand-receptor interactions. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8470–8476. doi: 10.1021/bi801208b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmer W, Focke M, Kolarich D, Dalik I, Gotz M, Jarisch R. Identification by immunoblot of venom glycoproteins displaying immunoglobulin E-binding N-glycans as cross-reactive allergens in honeybee and yellow jacket venom. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:460–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal C, Sanmartin C, Armisen M, Rodriguez V, Linneberg A, Gonzalez-Quintela A. Minor interference of cross-reactive carbohydrates with the diagnosis of respiratory allergy in standard clinical conditions. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;157:176–185. doi: 10.1159/000324447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm GJ, Jin C, Kranzelbinder B, Hemmer W, Sturm EM, Griesbacher A, et al. Inconsistent results of diagnostic tools hamper the differentiation between bee and vespid venom allergy. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e20842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focke M, Marth K, Flicker S, Valenta R. Heterogeneity of commercial timothy grass pollen extracts. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1400–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linneberg A, Fenger RV, Husemoen LL, Vidal C, Vizcaino L, Gonzalez-Quintela A. Immunoglobulin E sensitization to cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants: epidemiological study of clinical relevance and role of alcohol consumption. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;153:86–94. doi: 10.1159/000301583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) inhibition in different test formats – additional cases.

Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) inhibition using the Siemens Immulite 2000 with 3gAllergy Specific IgE Universal Kit.