Abstract

The PHR (Pam/Highwire/RPM-1) family of ubiquitin E3 ligases plays conserved roles in axon patterning and synaptic development. Genetic modifier analysis has greatly aided the discovery of the signal transduction cascades regulated by these proteins. In Caenorhabditis elegans, loss of function in rpm-1 causes axon overgrowth and aberrant presynaptic morphology, yet the mutant animals exhibit little behavioral deficits. Strikingly, rpm-1 mutations strongly synergize with loss of function in the presynaptic active zone assembly factors, syd-1 and syd-2, resulting in severe locomotor deficits. Here, we provide ultrastructural evidence that double mutants, between rpm-1 and syd-1 or syd-2, dramatically impair synapse formation. Taking advantage of the synthetic locomotor defects to select for genetic suppressors, previous studies have identified the DLK-1 MAP kinase cascade negatively regulated by RPM-1. We now report a comprehensive analysis of a large number of suppressor mutations of this screen. Our results highlight the functional specificity of the DLK-1 cascade in synaptogenesis. We also identified two previously uncharacterized genes. One encodes a novel protein, SUPR-1, that acts cell autonomously to antagonize RPM-1. The other affects a conserved protein ESS-2, the homolog of human ES2 or DGCR14. Loss of function in ess-2 suppresses rpm-1 only in the presence of a dlk-1 splice acceptor mutation. We show that ESS-2 acts to promote accurate mRNA splicing when the splice site is compromised. The human DGCR14/ES2 resides in a deleted chromosomal region implicated in DiGeorge syndrome, and its mutation has shown high probability as a risk factor for schizophrenia. Our findings provide the first functional evidence that this family of proteins regulate mRNA splicing in a context-specific manner.

Keywords: rpm-1, DLK-1 MAPKKK cascade, synapse development, ESS-2/DGCR14, mRNA splicing

PROPER synapse development ensures precise wiring and efficient transmission of information in the nervous system. In the presynaptic terminals, dense and organized accumulation of synaptic vesicles around the docking site called active zone is essential for rapid release of neurotransmitters (Sudhof 2012). Forward genetic screens in Caenorhabditis elegans, aided by visualization of synapse morphology using fluorescent reporters, have made important contributions to uncover conserved genes and pathways regulating presynaptic assembly (Jin and Garner 2008; Ou and Shen 2010). Many such screens have identified a common set of genes that regulate specific aspects of presynaptic differentiation in many neurons (Ackley and Jin 2004; Jin 2005; Maeder and Shen 2011). Among them are SYD-2/α-Liprin (LAR interacting protein), which has a central role in presynaptic active zone formation (Zhen and Jin 1999; Dai et al. 2006); SYD-1, a PDZ-RhoGAP protein that acts upstream of SYD-2 (Patel and Shen 2009; Hallam et al. 2002); and RPM-1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that regulates synaptic organization (Schaefer et al. 2000; Zhen et al. 2000).

Despite their strong defects in synaptic morphology, single loss-of-function (lf) mutants of rpm-1, syd-1, or syd-2 generally exhibit subtle to mild impairment in most behavioral assays. However, double mutants of rpm-1(lf) with syd-1(lf) or syd-2(lf) show more severe uncoordinated movement than expected from simple additivity of the single mutants (Liao et al. 2004; Nakata et al. 2005), indicating that rpm-1 acts in parallel to syd-1 and syd-2. This synthetic behavioral deficit of double mutants has allowed powerful selections for genetic suppressor mutations. Previous characterization of multiple rpm-1(lf) suppressors uncovered the DLK-1 MAP kinase pathway, consisting of dlk-1/MAPKKK, mkk-4/MAPKK, pmk-3/MAPK, and mak-2/MAPKAP2, uev-3/E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme variant, and cebp-1, a bZip-domain transcription factor acting downstream of the DLK-1 kinase cascade (Nakata et al. 2005; Yan et al. 2009; Trujillo et al. 2010). Further analysis of specific DLK-1 missense alterations also provided key insights into the mechanism of DLK-1 activation (Yan and Jin 2012). In addition, the identification of a gain-of-function allele of syd-2 as a suppressor of syd-1 revealed the order of activity in presynaptic active zone assembly (Dai et al. 2006).

To gain a more complete understanding of the genetic interaction landscape on the behavioral suppression of rpm-1; syd-1 or rpm-1; syd-2, here, we have characterized 95 suppressors. We uncovered a new allele of the sup-5 amber suppressor gene as the sole mutation suppressing syd-2. Of the 94 rpm-1 suppressors, 92 affected previously known components of the DLK-1 cascade. Interestingly, although the MLK-1 kinase cascade acts in parallel to the DLK-1 pathway in axon regeneration (Nix et al. 2011), we did not identify any mutations in the MLK-1 cascade in our screen. We showed that the loss-of-function mutations in this pathway do not suppress rpm-1 developmental defects. Of the two remaining rpm-1 suppressors, one defined a novel gene supr-1. The other suppressor resulted in a loss of function in the homolog of the human DGCR14 gene, ess-2. Our analysis of a synthetic interaction between ess-2 and a splicing mutation of dlk-1 provides the first evidence that ess-2 is functionally important in mRNA splicing.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans genetics and strains

We maintained C. elegans strains on NGM plates as described (Brenner 1974). We used juIs1[Punc-25-SNB-1::GFP] (Hallam and Jin 1998) to visualize presynaptic terminals of GABAergic motor neurons, muIs32[Pmec-7-GFP] (Ch’ng et al. 2003) for axonal morphology of mechanosensory neurons. All strains were maintained at 22.5°. Mutations and integrated lines were generally outcrossed to N2 more than four times before analyses. Strains and their genotypes are summarized in Supporting Information, Table S2.

Suppressor screen, genetic mapping, and whole-genome sequencing

Screens for suppressors of syd-1(lf); juIs1; rpm-1(lf) or juIs1; rpm-1(lf); syd-2(lf) were carried out using ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) mutagenesis following standard procedures as described (Brenner 1974; Nakata et al. 2005). These double-mutant animals had minimal voluntary movements and could not move continuously even upon physical stimulation such as tapping. Suppressed worms showed continuous sinusoidal movements although they were slower than wild type (Figure S2). We first sorted new suppressors into complementation groups by testing known loci, following the scheme shown in Figure S1. We then determined the molecular lesions in these mutations by Sanger sequencing. The remaining candidates were either sequenced for the coding sequences of mak-2, uev-3, and cebp-1 or subjected to whole-genome sequencing (WGS). In brief, genomic DNA was prepared from three 15-cm plates for each strain using Puregene Cell and Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified genomic DNAs were analyzed at Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI Americas). The obtained raw sequences were compared to the reference sequences in the WormBase using MAQGene software (Bigelow et al. 2009). By subtracting common variants among the cohort of suppressor strains, we determined unique homozygous single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants for each strain. We then outcrossed each suppressor strain to N2 and performed further linkage analysis on the isolated recombinants based on the phenotypic suppression using the unique SNPs. ju1041 was mapped to the middle of chromosome III, in a region containing the mutation in sup-5 gene. ju1118 was mapped to the middle of chromosome I, and only supr-1 had a premature stop codon in this region. The suppression in CZ5301 dlk-1(ju600)I; syd-1(ju82)II; ess-2(ju1117)III; juIs1IV; rpm-1(ju44)V showed linkage to two regions, the right arm of chromosome I and the middle of chromosome III. We found a splice mutation in dlk-1 on chromosome I. Complementation test of dlk-1(ju600) to dlk-1(0) showed that dlk-1(ju600) per se has no noticeable suppression on behavioral phenotypes of syd-1(lf); rpm-1(lf). We then found a premature stop codon mutation in the ess-2 gene on chromosome III to be necessary for the suppression of rpm-1(lf).

Behavioral analysis using a multiworm tracker

Locomotion speed was recorded using an automated multiworm tracking system as previously described (Pokala et al. 2014). Briefly, to restrict animal movement to the tracking area, filter paper with a 1-square-inch hole was soaked with 100 mM CuCl2 solution and placed onto a food-free agar plate. Ten young adult worms were transferred to a food-free assay plate after briefly washing in M9 solution, and allowed to crawl for 20 min before recording. Video recordings were acquired at 3 Hz using Streampix software (Norpix, Quebec, Canada) and a PL B-741F camera (PixeLINK, Ontario, Canada) with a Zoom 7000 lens (Navitar, Rochester, NY), and were analyzed with custom software written in MATLAB (Mathworks). The average velocity of forward locomotion was obtained from 5–10 worms for each session, and three sessions were averaged to obtain the average speed for each genotype.

DNA constructs

cDNAs were amplified from an N2 cDNA library using gene-specific primers shown below. The cDNAs were cloned into pCR8 or pDONR221 vector to make entry clones compatible with the Gateway system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the DNA sequences were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Wild-type (wt) ess-2 cDNA (F42H10.7b in WormBase, 1596 bp including ATG to the stop codon; see Figure 5A) was cloned using the primers YJ9222: 5′-ATGtcgtcgttcgacaaaaat-3′ and YJ9172: 5′-TTAgaaaaagtctccagcatt-3′ (pCZGY2377). ess-2(ju1117) and ess-2(ok3569) cDNAs (pCZGY2552 and pCZGY2553) were cloned from the cDNA libraries obtained from each mutant strain. These entry vectors were recombined with Pmec-4-GTW (pCZGY553) to make Pmec-4–ESS-2 (wt, pCZGY2379; ju1117, pCZGY2554; ok3569, pCZGY2555) for the rescue experiments. pCZGY2377 was recombined with Pmec-4–GFP–GTW (pCZGY603) to generate Pmec-4–GFP::ESS-2 (pCZGY2381). To construct GFP-tagged ESS-2, ess-2 cDNA (1587 bp without stop codon) was cloned using the primers (YJ9222 and YJ10311: 5′-gaaaaagtctccagcatttgc-3′). This entry clone (pCZGY2378) was recombined with Pmec-4–GTW–GFP (pCZGY858) to make Pmec-4–ESS-2::GFP (pCZGY2380). supr-1 cDNA (Y71F9AR.3 in WormBase, 2241 bp including ATG to the stop codon) was cloned using the primers YJ10312: 5′-ATGaagctagaggattcttgtgcc-3′ and YJ10313: 5′-TCAatgttctaaatttttcgaaacaat-3′. This entry clone (pCZGY2382) was recombined with pCZGY553 or pCZGY603 to generate Pmec-4–SUPR-1 (pCZGY2383) or Pmec-4–GFP::SUPR-1 (pCZGY2384). A short isoform of supr-1 lacking exon 4 (see Figure 3A) was identified, but not used in this study. rpm-1 cDNA (C01B7.6 in WormBase) was cloned into pDONR221 vector as three restriction enzyme-digested fragments ligated into one piece (pCZGY2005). GFP was inserted into the PstI site (pCZGY2017). This entry vector was recombined with Prgef-1–GTW (pCZGY66) to make Prgef-1–RPM-1::GFP (pCZGY2551).

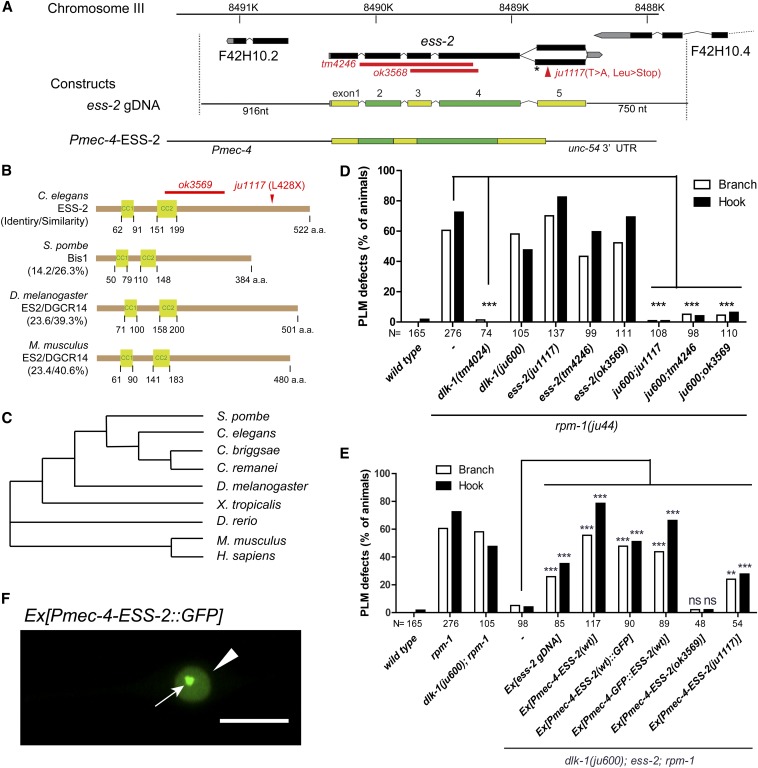

Figure 5.

dlk-1(ju600) splice acceptor mutation suppresses rpm-1(lf) together with ess-2(lf). (A) Schematic diagram of the genomic locus of ess-2 and the DNA constructs for transgenes. The ess-2 locus produces two isoforms, a and b (F42H10.7a and b in WormBase) that differ in six extra nucleotides at the beginning of exon 5 (asterisk). (B) Schematic diagrams of the domain structures of ESS-2 and its orthologs. Light green boxes indicate putative coiled-coil domains. (C) Dendrogram of the ESS-2 orthologs. The dendrogram was made using Clustal Omega. The names of ESS-2 homologs and accession nos. in UniProt are S. pombe: Bip1, O59793; C. elegans: ESS-2, P34420; C. briggsae: ESS-2, A8XT26; C. remanei: ESS-2, E3MI09; Drosophila melanogaster: ES2/DGCR14, O44424; Xenopus tropicalis, DGCR14, B1H164; Danio rerio: DGCR14, F1QAX0; Mus musculus: ES2/DGCR14/DGSI, O70279; and Homo sapiens: ES2/DGCR14/DGSI, Q96DF8. (D and E) The fraction of worms showing the defects of PLM axonal morphologies, as described in Figure 3, A and B. N = no. of animals. Statistics: Fisher’s exact test, compared with rpm-1(ju44) to show suppression in D and with dlk-1(ju600); ess-2(tm4246); rpm-1(ju44) to show rescue activity in E. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; ns, not significant (P > 0.05). (F) Localization of ESS-2 in the PLM mechanosensory neuron was visualized by a transgene juEx5859[Pmec-4-ESS-2::GFP]. Arrowhead and arrow indicate nucleus and punctum, respectively. Bar, 20 µm.

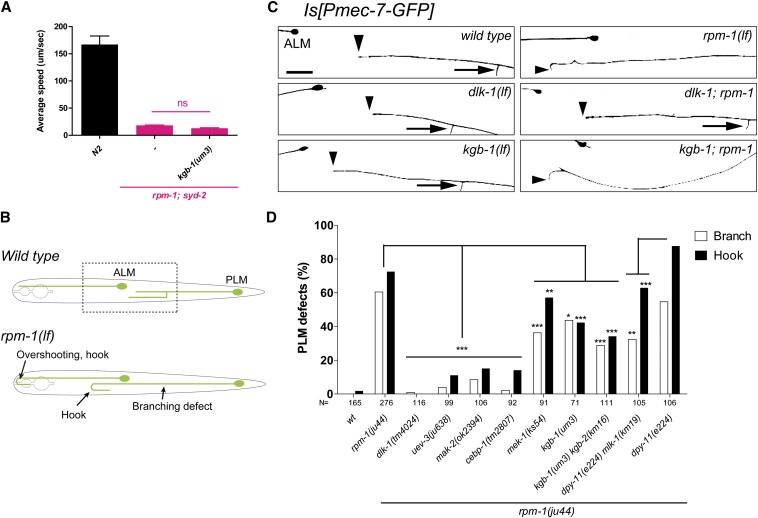

Figure 3.

Loss of function in the core components of the MLK-1 cascade has modest effects on rpm-1(lf) developmental phenotypes. (A) The average velocities of the forward movement of the worms were analyzed as in Figure 1B. n = 3 sessions, 5–10 worms in each session. Error bar indicates SEM. Statistics: one-way ANOVA; ns, not significant (P > 0.05). (B) Schematic diagram of Anterior Lateral Microtubule (ALM) and PLM mechanosensory neurons shown in light green. In rpm-1(lf) mutants, ALM and PLM overshoot and hook back, and PLM shows no branch in ∼50% of the animals (Schaefer et al. 2000). The micrographs of boxed region are shown in C. (C) The ALM and PLM were visualized by muIs32[Pmec-7-GFP] for the indicated genotypes. Arrows and arrowhead represent the axonal branch and tip of PLM neurons, respectively. Bar, 20 µm. (D) Fraction of worms showing PLM defects. Open bars and solid bars indicate branching and hook defects, respectively. N = no. of animals. dpy-11(e224) was used as a control for dpy-11(e224) mlk-1(km19). Statistics: Fisher’s exact test, compared with rpm-1(ju44) to show suppression. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Generation of transgenic C. elegans

Multicopy transgenic animals were generated as described (Mello et al. 1991). Pttx-3–RFP was used as a coinjection marker to adjust the total amount of DNA to 100 ng/μl. To rescue ess-2, we amplified the genomic fragment from N2 lysis using YJ10528: 5′-ccggccaaaggaacatccgaac-3′ and YJ10529: 5′-aagtggataaaggtccggcaaga-3′, and the DNA products were purified and injected into CZ17517 dlk-1(ju600); muIs32; ess-2(tm4246); rpm-1(ju44) at 1 ng/μl. pCZGY2379, pCZGY2554, or pCZGY2555 at 10 ng/μl was injected into CZ17517. pCZGY2383 at 10 ng/μl was injected into CZ17724 supr-1(ju1118); muIs32; rpm-1(ju44) animals. For GFP-tagged ESS-2 and SURP-1 the following constructs were injected to test their rescue activities: pCZGY2380 or pCZGY2381 at 90 ng/μl was injected into CZ17517. pCZGY2384 at 10 ng/μl was injected into CZ17724. These strains were outcrossed to N2 to get rid of all the background mutations to observe GFP signals. In general, more than three lines were analyzed for each construct, and quantification data of one representative line was shown. For RPM-1::GFP transgene (juEx3996), pCZGY2383 at 50 ng/μl was injected into CZ1234 rpm-1(ju23) animals. This extrachromosomal array (juEx3996) was integrated into a chromosome to generate juIs390 following ultraviolet trimethylpsoralen (UV/TMP) mutagenesis.

RNA preparation, RT-PCR, and qRT-PCR

Young adult worms were collected from three 60-mm NGM plates. Total RNA was extracted from whole animals using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with DNase I (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) for 20 min at 37°. Two micrograms of total RNA were reverse transcribed into cDNA using random primers and the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis system (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For semiquantitative RT-PCR, cDNA fragments were amplified using the primers: dlk-1 pair flanking ju600 mutation site (YJ10323: 5′-gtcgaaacccagcctgaac-3′ and YJ10324: 5′-ctcggtctccttcagttg-3′; see Figure 6A), dpy-1 pair flanking e128 mutation site (D1: 5′-cacattttcaagtgaagacttgag-3′ and D2: 5′-ggtcctggaatgcaacatcct-3′) (Aroian et al. 1993), and ama-1 pair (YJ2492: 5′-gcattgtctcacgcgttcag-3′ and YJ2493: 5′-ttcttccttctccgctgctc-3′) as a control and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. For quantitative RT-PCR Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) the kit was used for the reactions and the products were detected in real time using the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection system. cDNAs were amplified using the following primer pairs in which forward or reverse primers were designed to anneal the exon–exon junction to avoid amplification from genomic DNA (see Figure 6A): dlk-1 exon 3–4 pairs (YJ10317: 5′-gggctcttttcgtgttttcagc-3′ and YJ10318: 5′-cctcggatttttcaatttcaactg-3′), dlk-1 exon 5–6 pairs (YJ10319: 5′-tgttggaacaaacattctgagcc-3′ and YJ10320: 5′-ggagaatgagggacgattgcg-3′), dlk-1 exon 8–9 pairs (YJ10321: 5′-gcgaatccgccaaaaatcctac-3′ and YJ10322: 5′-cggaatccctggccggtgat-3′), and ribosomal subunit S25 (rps-25) pairs as an internal control (rps-25 F: 5′-ctctacaaggaggtcatcacc-3′ and rps-25 R: 5′-gacctgtccgtgatgatgaacg-3′). The dlk-1 mRNA levels were normalized to rps-25 for each product and then normalized to the control strain.

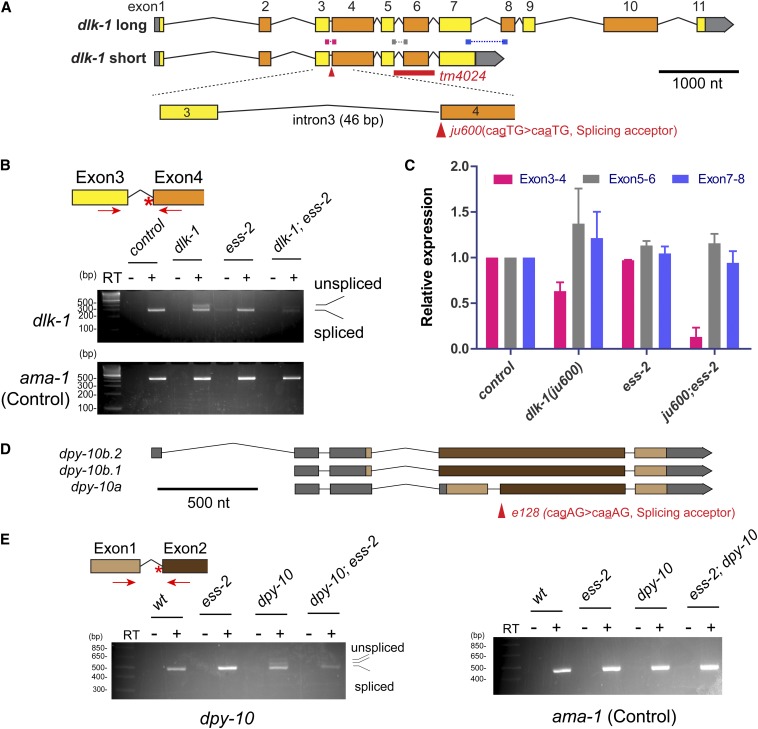

Figure 6.

ESS-2 regulates mRNA splicing of cryptic transcripts. (A and D) Schematic diagrams of genomic loci of dlk-1 and dpy-10. The dlk-1 locus produces at least two isoforms, long (F33E2.2a) and short (F33E2.2c). ju600 is a G-to-A substitution mutation located in the splice acceptor site of intron 3 as indicated by the arrowhead. Primers used for qRT-PCR in C are shown as bars and dashed lines between long and short isoforms. (B and E) Amounts of PCR products were analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR using dlk-1 or dpy-1 primers (red arrows). The positions of splice acceptor mutations in dlk-1(ju600) and dpy-10(e128) are shown by asterisks. The predicted sizes of spliced and unspliced fragments are indicated on the right side. ama-1 encoding a large subunit of RNA polymerase II was used as a control. (C) Amounts of PCR products were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. The colors of bars match the amplified fragments indicated in A. All the strains in this experiment have muIs32[Pmec-7-GFP] and rpm-1(ju44) in the background. Error bar represents SEM; n = 2 biological replicates.

Bright-field and fluorescence microscopy

Bright-field images were photographed using a Leica MZ95 stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). For quantification of the morphology of mechanosensory neurons using muIs32[Pmec-7-GFP] reporter, young adults were immobilized in 1% phenoxypropanol (TCI America, Portland, OR) in M9 buffer and scored under a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope equipped with Chroma HQ filters and a ×63 (NA = 1.4) objective lens. Images of the fluorescent reporters were collected from young adults immobilized in M9 with 1% phenoxypropanol using a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope equipped with ×63 (NA = 1.4) or ×100 (NA = 1.46) objective lens. Images shown are maximum-intensity projections obtained from several z-sections (0.5–1.0 µm/section).

Electron microscopy

CZ333 juIs1, CZ840 juIs1; rpm-1(ju41); syd-2(ju37), and CZ1797 syd-1(ju82); juIs1; rpm-1(ju44) young adult animals were fixed using glutaraldehyde and osmium as described (Hallam et al. 2002). Midanterior body was serially sectioned at 40–50 nm thickness. The ventral and dorsal nerve cords were photographed using a JEOL 1200EX transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 80 kV. Presynaptic terminals of neuromuscular junctions were defined by the existence of clear synaptic vesicles and electron-dense active zones. The types of the motor neurons, cholinergic or GABAergic, were defined by the synaptic connections (White et al. 1986). Synaptic vesicles were morphologically determined as 35–50 nm clear vesicles, and their numbers were manually counted in the sections containing the active zone.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the rpm-1(lf) phenotypes of the mechanosensory neurons using Fisher’s exact test in GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Locomotion speed and synaptic vesicle numbers were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test in GraphPad Prism 5.0.

Results

Presynaptic development is severely disrupted in double mutants of rpm-1 with syd-1 or syd-2

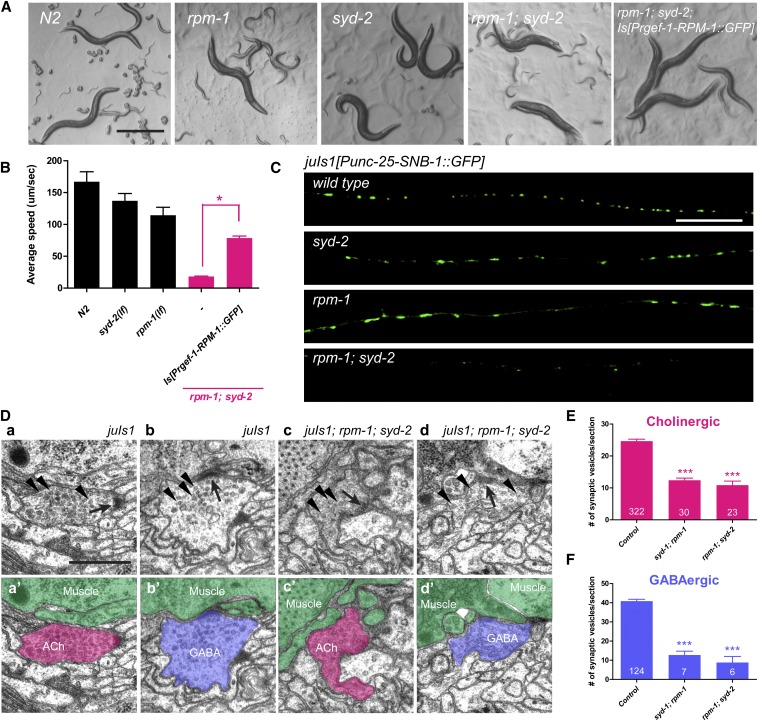

We previously reported that null (0) mutations of rpm-1 result in disorganized synapses (Zhen et al. 2000), and null mutations of syd-1 or syd-2 alter presynaptic active zone assembly (Zhen and Jin 1999; Hallam et al. 2002). By gross movement, rpm-1(0) is indistinguishable from wild type, and syd-1(0) and syd-2(0) show slow movement while maintaining sinusoidal pattern (Figure 1, A and B). Strikingly, rpm-1; syd-1 and rpm-1; syd-2 double mutants show severely uncoordinated behavior from young larvae throughout mature adults (Figure 1B). Their body size and brood size are also smaller than wild-type animals or each single mutant (Figure 1A, and data not shown). We quantified locomotion behavior using a multiworm tracker. Wild-type worms showed a coordinated sinusoidal movement, with an average forward locomotion speed of 167.1 ± 15.6 µm/sec. While movement speed for each single mutant was similar to that of wild type, the rpm-1; syd-2 double mutants greatly reduced the speed to 18.2 ± 0.7 µm/sec (mean ± SEM, n = 3 experiments, 5–10 worms/experiment) (Figure 1, A and B). Panneuronal expression of rpm-1(+) using a transgene juIs390[Prgef-1-RPM-1::GFP] rescued both the uncoordinated behavior and small body size of rpm-1; syd-2 double mutants (Figure 1, A and B), suggesting that the behavioral and body size defects arise from the loss of rpm-1 function in neurons and that the body size may be a secondary effect associated with severe paralysis.

Figure 1.

rpm-1(lf) synergizes with syd-1(lf) and syd-2(lf) to impair locomotion and presynaptic morphologies. (A) Bright-field images showing the body shapes of adult animals for the indicated genotypes. Bar, 500 µm. (B) Locomotion speed of worms for the indicated genotypes was analyzed using a multiworm tracker. Average velocity of the forward movement was calculated for 15-min sessions. Error bar indicates SEM. Statistics: one-way ANOVA, *P < 0.05. (C) Presynaptic terminals in the dorsal cord visualized by juIs1[Punc-25-SNB-1::GFP], genotype of animals indicated. In rpm-1(lf) mutant, the numbers of presynaptic terminals are decreased and remaining synapses either overdeveloped or immature (Zhen et al. 2000). syd-2(lf) mutants have comparable number of synapses but the synaptic vesicles show diffused pattern (Zhen and Jin 1999). Hardly any SNB-1::GFP was observed in rpm-1(lf); syd-2(lf). Bar, 20 µm. (D) Electron micrographs of presynaptic terminals. Arrowheads and arrows in a–d indicate synaptic vesicles and active zones, respectively. In a′–d′ presynaptic varicosities of cholinergic and GABAergic neurons are shown in magenta and blue, respectively. Muscles are shown in green. AZ, active zone. Bar, 500 nm. (E and F) Average number of synaptic vesicles in sections containing active zones was analyzed for cholinergic neurons (E) and GABAergic neurons (F). n = no. of sections. Error bar indicates SEM. Statistics: one-way ANOVA, compared with control. ***P < 0.001. Alleles and transgene used: rpm-1(ju23), rpm-1(ju44), rpm-1(ju41), syd-1(ju82), syd-2(ju37), and juIs390[Prgef-1-RPM-1::GFP].

The behavioral deficits of these double mutants are strongly correlated with severe disruption of synapses in many neurons. The motor neurons form en passant synapses onto ventral and dorsal body wall muscles (White et al. 1986). A synaptic vesicle marker such as juIs1[Punc-25-SNB-1::GFP] readily enables visualization of the presynaptic terminals of GABAergic motor neurons (Figure 1C) (Hallam and Jin 1998). rpm-1, syd-1, and syd-2 single mutant animals each display distinctive alterations in presynaptic morphology, as previously described (Figure 1C) (Zhen and Jin 1999; Zhen et al. 2000; Hallam et al. 2002). In rpm-1; syd-1 or rpm-1; syd-2 double mutants, SNB-1::GFP puncta were barely detectable in the presumed presynaptic regions along the nerve processes (Figure 1C). Examination of several synaptic markers in other types of neurons revealed similar reduction in synapse number and abnormal synapse morphology (data not shown). The morphological defects of presynaptic terminals were observed from young larvae through adults, consistent with the behavioral deficit throughout development.

We further examined the presynaptic architecture of motor neurons using electron microscopy on serial ultrathin sections. Presynaptic terminals of these neurons are identified as axonal swellings containing clusters of synaptic vesicles and electron dense active zones (Figure 1D) (White et al. 1986). We analyzed segments of ventral and dorsal nerve cords (∼250 sections, corresponding to ∼11.25 µm) in two mutant strains (syd-1; juIs1; rpm-1 and juIs1; rpm-1; syd-2) and juIs1 as a control. Both double mutants displayed dramatically reduced numbers of synapses in cholinergic and GABAergic motor neurons (Table 1 and Figure 1, E and F). Furthermore, the few remaining synapses contained very few synaptic vesicles that were scattered near the presynaptic dense projections (Figure 1, D–F), indicating that presynaptic terminals were poorly developed and/or maintained in the double mutants. These analyses show that the rpm-1 pathway and the presynaptic active zone assembly pathway via syd-1/syd-2 function in parallel to promote presynaptic development.

Table 1. Severe reduction of synapse number and synaptic vesicles in rpm-1; syd-1 or rpm-1; syd-2 mutants.

| Genotype | Nerve cord | Type | No. of synapses/10 µm | Average length of synapses, µm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| worm1 | worm2 | ||||

| juIs1 | VC | ACh | 8.7 | 4.4 | 0.58 ± 0.03 (n = 49) |

| GABA | 4.2 | 1.8 | 0.86 ± 0.05 (n = 23) | ||

| DC | ACh | 5.1 | 4.9 | 0.66 ± 0.05 (n = 34) | |

| GABA | 2.4 | 1.8 | 1.01 ± 0.07 (n = 15) | ||

| juIs1; rpm-1(ju41); syd-2(ju37) | VC | ACh | 1.8 | 3.6 | 0.47 ± 0.06 (n = 6) |

| GABA | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.50 ± 0.09 (n = 2) | ||

| DC | ACh | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.47 ± 0.11 (n = 2) | |

| GABA | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.36 (n = 1) | ||

| syd-1(ju82); juIs1; rpm-1(ju44) | VC | ACh | 0.0 | 4.4 | 0.68 ± 0.10 (n = 5) |

| GABA | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.54 (n = 1) | ||

| DC | ACh | 0.0 | 6.2 | 0.43 ± 0.06 (n = 7) | |

| GABA | 0.9 | 1.8 | 0.56 ± 0.11 (n = 3) | ||

Young adult worms were chemically fixed, processed, and serially sectioned. The ventral and dorsal cords of two worms per genotype were examined by electron microscope. Numbers of sections analyzed were ∼1000 for juIs1 worm 1 (45 µm), ∼500 for juIs1 worm 2 (22.5 µm), and ∼250 for the others (11.25 µm). The synapses were defined as a varicosity containing synaptic vesicles and one or a few active zones (White et al. 1986). Synaptic vesicles were counted in the sections containing an active zone and averaged over sections. The length of a synapse was calculated by multiplying the number of sections containing synaptic vesicles by 50 nm. n = no. of synapses.

Most suppressors of the developmental defects of rpm-1 affect the DLK-1 kinase cascade

We exploited the synthetic locomotor deficits of rpm-1; syd-1 and rpm-1; syd-2 double mutants to select for mutations that improved movement (see Materials and Methods). Subsequent analyses of the GABAergic presynaptic morphology using the Punc-25-SNB-1::GFP marker allowed us to sort the suppressor mutations into groups that displayed specific suppression on each gene. Although the screen should have an equal chance to isolate mutations suppressing either gene, of the 95 suppressors analyzed, we found only one allele, ju1041, that specifically suppressed syd-2(ju37), but not rpm-1(lf) (data not shown). syd-2(ju37) results in an amber stop codon at Glu397 (Zhen and Jin 1999). We mapped ju1041 to the middle of chromosome III (Figure 2C) and identified a single nucleotide change from C to T in sup-5, a tryptophan tRNA (see Materials and Methods). The mutated tRNA in ju1041 can encode tryptophan for the amber stop codon as previously described (Waterston and Brenner 1978; Wills et al. 1983). The isolation of sup-5(ju1041) as the only suppressor of syd-2(ju37) suggests that few genes can be mutated to bypass the requirement for syd-2(lf) in synapse development and function.

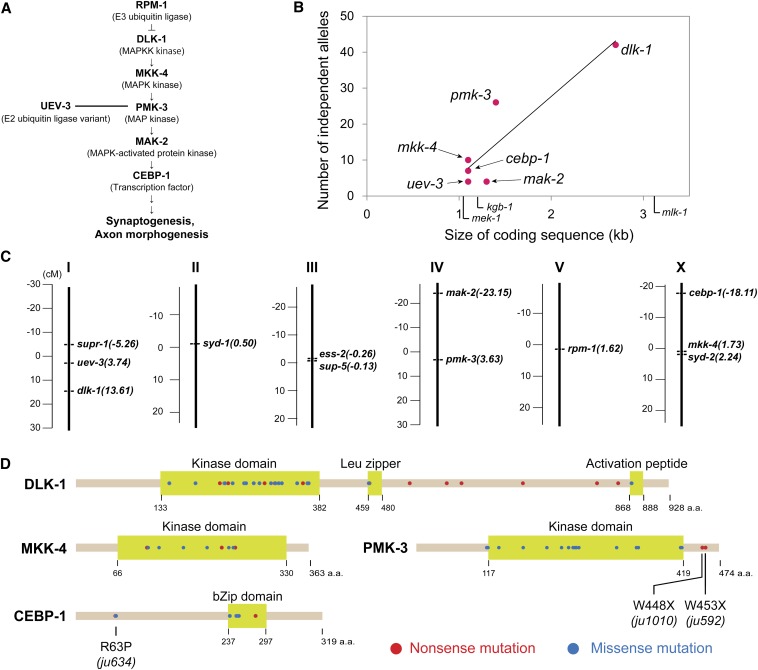

Figure 2.

Most of the rpm-1(lf) suppressors are mutations in the core components of the DLK-1 cascade. (A) Schematic diagram of the known components of the DLK-1 pathway. E3 ubiquitin ligase RPM-1 down-regulates DLK-1 MAPKK kinase by degradation. (B) The total number of alleles for each gene in the DLK-1 cascade independently isolated in the suppressor screen was plotted against the length of the coding sequence. The method of “least squares” was used to obtain the linear approximation. The line represents y = 22.1x − 16.6. R2 = 0.81112. The sizes of mlk-1, mek-1, and kgb-1 are shown along the x-axis; no mutations were identified for these genes in our screen. (C) Genetic positions of the rpm-1, syd-1, syd-2, and their suppressor genes on the C. elegans chromosomes. Unit represents centimorgans (cM). (D) The positions of nonsense (red) and missense (blue) mutations isolated in the screen are plotted along the protein sequences. Functionally defined domains are shown as light green boxes. Positions of select alleles are indicated under the protein sequences (see Results).

The remaining 94 suppressors we characterized were specific for rpm-1. We previously reported multiple rpm-1 suppressors that cause loss of function in components of the DLK-1/MKK-4/PMK-3 MAP kinase pathway (Figure 2A and Figure S2) (Nakata et al. 2005; Yan et al. 2009; Trujillo et al. 2010). We therefore devised a complementation workflow to test whether new suppressors affected these known genes (Figure S1 and Materials and Methods). Among 94 suppressors, 41 were determined to be alleles of dlk-1 and 26 were alleles of pmk-3 (Figure 2B and Table S1). Among the new suppressors that were not dlk-1 or pmk-3, some were linked to syd-2 on the X chromosome, where mkk-4 and cebp-1 reside (Figure 2C and Figure S2). Subsequent DNA sequencing analysis of candidate genes, in conjunction with whole-genome sequencing of selected suppressors, revealed single nucleotide changes in all six genes of the DLK-1 pathway, as summarized in Table S1 and Figure 2B. Most of the nucleotide changes in dlk-1, mkk-4, or pmk-3 are predicted to cause missense alterations in the kinase domains (Yan and Jin 2012) (Figure 2D, Figure S3, and Figure S4). Seven dlk-1 alleles, two pmk-3 alleles, and one mak-2 allele were independent isolates of the same nucleotide changes from different mutagenized parents, suggesting that the mutagenesis hits are likely saturated in the context of this screen for the behavioral suppression (Table S1). Among the collection of new alleles, we found several mutations that revealed potential roles of new functional domains. For example, two new alleles of pmk-3, ju1010 and ju592, are nonsense mutations after the kinase domain, suggesting that the C terminus of PMK-3 may regulate the protein activity or stability. cebp-1(ju634) altered arginine 63 to proline in the N terminus of the protein, whereas the majority of the previously reported cebp-1 mutations affect the bZip domain (Yan et al. 2009; Bounoutas et al. 2011) (Figure 2D and Table S1). In summary, 98% of the suppressor mutations identified in our screens affected the six genes of the DLK-1 kinase cascade (Figure 2A and Table S1), and the number of the identified alleles roughly correlated with the size of the coding regions of the genes (Figure 2B).

The MLK-1 kinase cascade has a minor role in the developmental phenotypes of rpm-1 mutants

Among other MAP kinase cascades in C. elegans (Sakaguchi et al. 2004), the MLK-1/MEK-1/KGB-1 pathway, has recently been shown to act in parallel to the DLK-1/MKK-4/PMK-3 pathway in axon regeneration (Nix et al. 2011). MLK-1::GFP expression levels are increased in rpm-1 mutants, suggesting MLK-1, like DLK-1, may be a substrate for degradation by RPM-1. The mlk-1, mek-1, and kgb-1 genes are comparable in size to the genes of the dlk-1 pathway (Figure 2B), and null mutants in these genes are viable and behaviorally normal. However, we found none of the suppressor mutations isolated in our screen affected the genes in the MLK-1 pathway (Table S1). We therefore constructed a strain of kgb-1(0); rpm-1(lf); syd-2(lf), and found no improvement on locomotor phenotype (Figure 3A). Previous studies showed that mlk-1(0) and mek-1(0) did not suppress the presynaptic defects in GABAergic neurons of rpm-1(lf) (Nakata et al. 2005). Here, to further assess the activity of the mlk-1/mek-1/kgb-1 in neuronal development, we analyzed the axonal development of mechanosensory neurons. In rpm-1(lf) mutants the Posterior Lateral Microtubule (PLM) neurons display highly penetrant axon overshooting and frequent absence of synaptic branches (Schaefer et al. 2000) (Figure 3, B–D). These PLM axon developmental defects of rpm-1(lf) are completely suppressed by loss-of-function mutations in the DLK-1 cascade (Yan et al. 2009; Trujillo et al. 2010) (Figure 3, C and D). In contrast, null mutations in mlk-1, mek-1, or kgb-1 showed rather mild suppression (Figure 3, C and D). kgb-2 is a closely related homolog of kgb-1, sharing 84% identity. We found that the kgb-1(0) kgb-2(0) double mutant also did not strongly suppress rpm-1(lf) PLM axonal defects (Figure 3D). This additional analysis demonstrates the highly specific regulation of the DLK-1/MKK-4/PMK-3 cascade by RPM-1 in synapse and axon development.

Loss of function in a novel protein SUPR-1 suppresses rpm-1(lf)

We mapped the rpm-1 suppressor mutation ju1118 to the middle of chromosome I, following whole-genome sequencing analysis (Figure 2C and Materials and Methods). We found a single nucleotide change, G875A, resulting in Trp292 to a stop codon mutation in the predicted geneY71F9AR.3, hereby named supr-1 (suppressor of rpm-1) (Figure 4A and Figure S5). supr-1(ju1118) was a weak suppressor by the criterion of locomotion behavior (data not shown). Quantification of the suppression of rpm-1(lf) on the PLM axon defects also showed that supr-1(ju1118) exhibited weaker suppression activity than those due to complete loss of function in the dlk-1 cascade (Figure 4B). We verified the supr-1 gene structure by RT-PCR and cDNA analysis. We identified two mRNA transcripts that differed in alternative exon 4, corresponding to two protein isoforms of 746 amino acids (long), and of 688 amino acids (short) (Figure 4A and Figure S5). To verify that supr-1 is the causative gene for suppressing rpm-1(lf) phenotypes, we expressed the SUPR-1 long isoform cDNA under the mechanosensory neuron-specific promoter (Pmec-4). This transgene fully rescued the suppression phenotypes of supr-1(ju1118) (Figure 4C), confirming that supr-1(ju1118) is a loss of function mutation, and further, indicating that SUPR-1 functions cell autonomously.

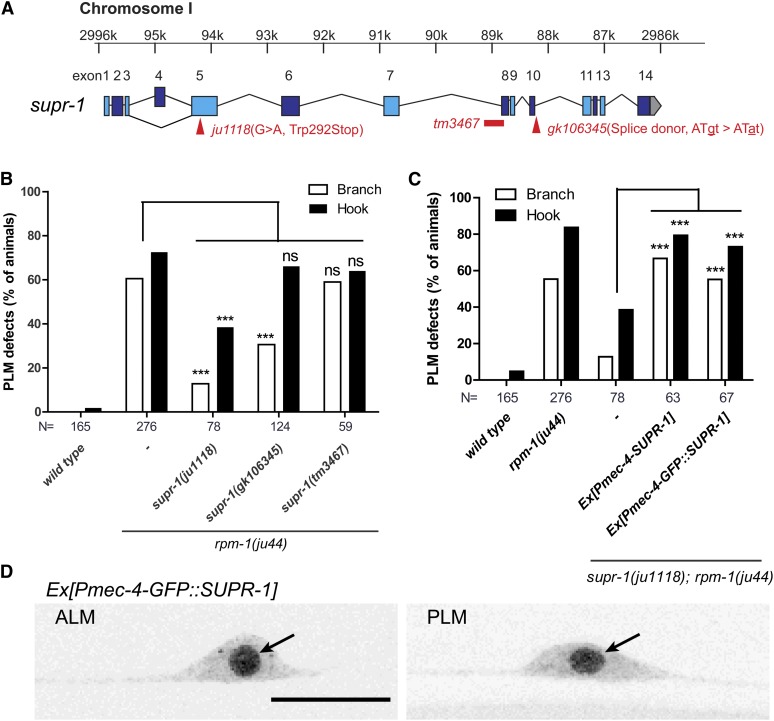

Figure 4.

supr-1 is a novel gene antagonizing rpm-1. (A) Schematic diagram of the genomic locus of supr-1 (Y71F9AR.3 in WormBase). There are two isoforms produced from the locus as described in Material and Methods, but we focused on the long isoform in this study. (B and C) The fraction of worms showing defects of PLM axonal morphologies, as described in Figure 3, A and B. N = no. of animals. Statistics: Fisher’s exact test, compared with rpm-1(ju44) to show suppression in B and with supr-1(ju1118); rpm-1(ju44) to show rescue activity in C. ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant (P > 0.05). (D) Localizations of SUPR-1 in the mechanosensory neurons were visualized by a transgene juEx5517[Pmec-4-GFP::SUPR-1]. Arrows indicate nucleus. Bar, 20 µm.

The predicted SUPR-1 protein lacks known functional domains and has closely related proteins in other Caenorhabditis species (Figure S5). To gain insights into SUPR-1 function, we examined its localization in mechanosensory neurons using GFP-tagged SUPR-1 (long). This GFP-tagged construct fully rescued the supr-1(ju1118) effects on rpm-1(lf) (Figure 4C). GFP::SUPR-1 was primarily localized in the nucleus and weakly detectable in the somatic cytoplasm and axon (Figure 4D). We also analyzed two additional mutations of supr-1, tm3467, and gk106345. tm3467 is a 327-bp deletion removing the splice acceptor site of intron 7 and a part of exon 8. gk106345 is a splice donor mutation in the exon 10/intron 10 junction (Figure 4A and Figure S5). mRNA may be produced from each allele using cryptic splice sites, but the encoded proteins would likely have an altered C-terminal region from Gly505 and Asn590 for tm3467 and gk106345, respectively. We found that tm3467 did not suppress the PLM morphological defects of rpm-1(lf), while gk106345 showed partial suppression, suggesting the SUPR-1 C terminus may likely be dispensible for its function (Figure 4B). Taken together, we identified a novel protein SUPR-1 that functions to antagonize rpm-1.

Loss of function in ess-2 synergizes with a splice acceptor mutation in dlk-1 to suppress rpm-1(lf)

In the course of analyzing a suppressor strain isolated from screening in the rpm-1(ju44); syd-1(ju82) background, we identified the ju600 allele as containing a single nucleotide change at the 3′ splice acceptor site (CAG to CAA) in the third intron of dlk-1. This change is predicted to result in the retention of intron 3 or skipping of exon 4, which would potentially lead to a premature stop codon before the kinase domain. However, we found that dlk-1(ju600) alone did not show detectable suppression on rpm-1(lf) (Figure 5D). By inspecting animals from outcrossing of the initial suppressor isolate, we detected a background-dependent suppression activity of dlk-1(ju600) that showed linkage to chromosome III. Through further genetic mapping using unique SNPs identified by whole-genome sequencing of the original suppressor strain, we identified a nonsense mutation in the ess-2 (ES2 similar) gene (Dimitriadi et al. 2010) as required for dlk-1(ju600) to suppress rpm-1(lf) (Figure 5D). ESS-2 consists of 522 amino acids, and ess-2(ju1117) alters leucine 428 to a stop codon (Figure 5, A and B). The ess-2(ju1117) single mutation did not suppress rpm-1(lf), but the dlk-1(ju600); ess-2(ju1117) double mutant suppressed rpm-1(lf), comparable to the suppression by a dlk-1 null allele (Figure 5D). We further analyzed two deletion alleles of ess-2, tm4246, and ok3569 (Figure 5A and Figure S6). tm4246 deletes a splice acceptor site of intron 1 through part of intron 4, and likely causes an early stop codon. ok3569 removes parts of exon 3 and exon 4. We performed RT-PCR on ok3569 animals and found that the remaining transcripts would result in an in-frame protein that lacks amino acids from Glu166 to Asp314 including a conserved coiled-coil domain (Figure 5B and Figure S6). Both ess-2 alleles showed no suppression of rpm-1(lf) on their own and acted as synthetic suppressors with dlk-1(ju600) (Figure 5D). Furthermore, we generated transgenes expressing full-length ess-2 genomic DNA, including 916 bp of the ess-2 promoter region, and observed rescue of the synthetic suppression effects of dlk-1(ju600); ess-2(tm4246) (Figure 5E). These data demonstrate that ess-2 is the causative gene for this synthetic suppression with dlk-1(ju600). A transcriptional reporter driven by 916-bp upstream sequences of ess-2 showed broad tissue expression, including neurons, pharynx, body wall muscles, and seam cells (data not shown). We thus generated transgenes expressing the ess-2 cDNA under the control of mechanosensory neuron-specific promoter and found that this expression fully rescued the synthetic suppression effects on PLM in a cell-autonomous manner (Figure 5E). We infer that the dlk-1(ju600) splice site mutation is a cryptic dlk-1 allele. Loss of function in ess-2 enhances ju600 to a complete loss of dlk-1 function, resulting in the observed synthetic suppression of rpm-1(lf).

ESS-2 is required for mRNA splicing of mutant dlk-1(ju600) transcripts

C. elegans ESS-2 is named after the human protein ES2, also known as DiGeorge syndrome critical region 14 (DGCR14) or DiGeorge syndrome protein I (DGSI) (Lindsay et al. 1996; Rizzu et al. 1996; Gong et al. 1997). This protein family is conserved from fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe to human and contains two conserved coiled-coil regions in its N-terminal based on the MARCOIL program (Delorenzi and Speed 2002) (Figure 5B and Figure S6). Both yeast homolog Bis1 and mouse ES2 are localized in the nucleus (Lindsay et al. 1998; Taricani et al. 2002). A recent large-scale protein interactome study identified human ES2/DGCR14 as a noncore component of the spliceosome C complex (Hegele et al. 2012), suggesting that the ESS-2 protein family might function in mRNA splicing.

To investigate how ESS-2 functions, we next examined ESS-2 protein localization. We tagged ESS-2 with GFP at either the N or C terminus. Both constructs are fully functional based on transgenic rescue activity (Figure 5E). GFP-tagged ESS-2 was primarily localized to the nucleus, with occasional detection of one or a few bright nuclear puncta (Figure 5F). Similar nuclear puncta have also been reported for the fission yeast homolog, Bis1 (Taricani et al. 2002). Expression of cDNA isolated from ess-2(ok3569) did not rescue ess-2(tm4246). Overexpression of cDNA containing ess-2(ju1117) mutation partially rescued ess-2(tm4246) (Figure 5E). This analysis suggests that the conserved coiled-coil domain is critical for ESS-2 function, and that C-terminally truncated ESS-2 protein produced in ess-2(ju1117) retains partial activity.

The observation that dlk-1(ju600) single mutants did not eliminate dlk-1 activity suggests that this mutant likely produces sufficient functional DLK-1, despite the mutation altering the conserved splice acceptor consensus sequence. Early studies have indicated that the CAG in the splice acceptor site can be dispensable for mRNA splicing in C. elegans (Aroian et al. 1993). We thus examined the splicing of intron 3 of dlk-1 by RT-PCR. Analysis of semiquantitative RT-PCR products showed that transcripts corresponding to the fully spliced transcripts were produced from dlk-1(ju600) animals to a comparable level of those from wild-type animals (Figure 6B). Sequence analysis also confirmed that mRNA splicing in dlk-1(ju600) used the same site as in dlk-1(wt) despite the nucleotide change at the splice acceptor site. On the other hand, transcripts corresponding to the unspliced transcript were only observed in dlk-1(ju600) (Figure 6B). In ess-2(tm4246) single mutants, we detected only fully spliced dlk-1 transcripts, similar to wild-type animals (Figure 6B). However, in dlk-1(ju600); ess-2(tm4246) double mutants the amount of fully spliced dlk-1 transcripts was significantly decreased, compared to dlk-1(ju600) and wild type (Figure 6B). It is possible that RT-PCR may not detect transcript intermediates, such as those stalled in a Lariat structure (see Discussion). To more accurately assess the effects on mRNA splicing, we performed quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), using primers to specifically detect the transcripts in which intron 3 appeared to be spliced out (Figure 6A, magenta). Consistent with the semiquantitative RT-PCR data, we observed no detectable changes in either dlk-1(ju600) or ess-2(ju1117) single mutant, compared to wild type. However, spliced transcripts without intron 3 were dramatically decreased in dlk-1(ju600); ess-2(ju1117) double mutant (Figure 6C, magenta). As a control for total mRNA level of dlk-1, we designed primers to detect exon 5–6 and exon 8–9 junctions (Figure 6A, gray and blue). qRT-PCR analysis showed that the amount of the dlk-1 transcripts was not altered in dlk-1(ju600); ess-2(ju1117) (Figure 6C, gray and blue), indicating that loss of function in ess-2 specifically affects intron 3 splicing of dlk-1.

We next asked if ESS-2 has a similar role in splicing of other genes. The dpy-10(e128) mutation alters the splice acceptor from CAG to CAA in intron 1 of isoform “a” (Figure 6D). We performed RT-PCR for this exon/intron junction and detected both spliced and unspliced transcripts in dpy-10(e128), consistent with a previous report (Aroian et al. 1993) (Figure 6E). In the dpy-10(e128); ess-2(tm4246) double mutant, however, both spliced and unspliced bands were significantly reduced, suggesting that ESS-2 affects splicing efficiency of dpy-10 transcripts when they carry the mutation in a splice acceptor site (Figure 6E). The effect of ess-2(lf) on the “a” isoform did not lead to further enhancement of dumpy body shape in ess-2(lf); dpy-10(e128) compared to dpy-10(e128), possibly because of residual activities of the “b” isoform (Figure 6D). Taken together, these data support a conclusion that ESS-2 acts to facilitate RNA splicing, particularly when pre-mRNA is compromised or contains noncanonical sequences at the splice acceptor site.

Discussion

Large-scale analysis of genetic suppressors of rpm-1 supports the functional specificity of the DLK-1 kinase cascade in synapse formation

Synapse formation is a terminal step in neuronal differentiation and involves coordinated action of multiple pathways, including recruitment and retention of synaptic vesicles, formation, and remodeling of synaptic cytoskeleton, assembly and alignment of junctional structures at pre- and postsynaptic sites. Genetic studies in C. elegans over the past decade have made important contributions to the delineation of key molecules and pathways in each specific aspect of synapse formation (Ackley and Jin 2004; Yan et al. 2011). Here, our analysis of rpm-1; syd-1 and rpm-1; syd-2 reinforces the notion that synaptogenesis is regulated by multiple parallel pathways. While removing each gene individually is not severely detrimental to animal behavior, these double mutants exhibit severely impaired movement, correlating to the dramatic reduction of synapse number and poorly developed remaining synapses. It is interesting to note that the locomotion defect of these double mutants is less severe than that of the kinesin unc-104(lf), in which synaptic vesicles are nearly depleted while the localization of synaptic active zone proteins appears to be unperturbed (Hall and Hedgecock 1991; Zhen and Jin 1999). The behavioral outcome of rpm-1(lf); syd-2(lf) might indicate that some residual neuronal activity remains in these animals due to compensation or use of different means of synaptic transmission.

We selected genetic suppressor mutations based on behavioral improvement of the uncoordinated locomotion of rpm-1 double mutants with syd-1 or syd-2. We can draw the following conclusions from the analyses of a large number of genetic suppressor mutations. First, among 94 rpm-1(lf) suppressor alleles, we found nine alleles that were independent hits of the same nucleotide. Although the small number of genes and high hit rate per gene preclude the classical application of the Poisson distribution (Pollock and Larkin 2004), we reckon that this screen is likely saturated for the major components of the DLK-1 pathway. The design of our suppressor screen biases against genes whose loss of function results in lethality or severe movement defects. Yet, we might expect to identify partial loss-of-function mutations in known essential genes as some suppressor mutations in the dlk-1 cascade show rather weak activity. The absence of such mutations leads us to speculate that other genes may only have minor roles or act in parallel to modulate the six core components of the dlk-1 cascade. Second, null mutants in the MLK-1/MEK-1/KGB-1 cascade are also homozygous viable; yet, our analysis indicates that this pathway does not have a major role in the context of synapse formation. The interaction between RPM-1 and this kinase pathway may be specific to other cellular contexts, such as axon regeneration (Nix et al. 2011). Third, most missense mutations in DLK-1/MKK-4/PMK-3 are in the kinase domains, highlighting the importance of the phosphor-relay in their action. The collection of functionally important mutations would provide additional information about how these proteins work when the three-dimensional structures of these proteins are available. Fourth, newly identified mutations in this study provide insights into how the components of the DLK-1 pathway function. For instance, the nonsense mutations in the C terminus of PMK-3 reside outside of the canonical kinase domain, implying its possible regulatory role. Furthermore, the missense mutation of CEBP-1 suggests an important role of the N terminus in its activity. As shown for other CEBP-1 orthologs, the N terminus of CEBP-1 may act as a transactivation domain (Pei and Shih 1991; Williams et al. 1995). Fifth, besides the core components of the DLK-1 kinase cascade, we identified a novel gene supr-1 that antagonizes rpm-1. The lack of known motifs precludes us from drawing strong conclusions regarding the function of supr-1. Nonetheless, the observation that it is predominantly localized to the nucleus of neurons suggests that it may act through transcriptional or post-transcriptional modulation. Future studies, such as identifying its binding partners and/or targets will address such possibilities. Lastly, although our suppressor screen has an equal chance to identify mutations suppressing the behavioral defects of syd-1 or syd-2, we found only a sup-5 mutation as a suppressor of syd-2(Q397X) (this study) and a gain-of-function mutation in syd-2 as a suppressor mutation of syd-1 (Dai et al. 2006). This outcome contrasts to the large number of suppressors of rpm-1, and clearly reflects the nature of signaling contexts of these two pathways. RPM-1 negatively regulates a signal transduction cascade that largely acts in a linear manner, while SYD-1 and SYD-2 function in a concerted manner to promote the proper assembly or organization of an ensemble of proteins in presynaptic dense projections.

The DGCR14 protein ESS-2 is a splicing factor that ensures accurate splicing in a context-dependent manner

Our analysis of ESS-2 has provided the first functional evidence supporting a role of the conserved family of DGCR14 in mRNA splicing. The splicing machinery and process are highly conserved among metazoans (Rothman and Singson 2011). In C. elegans the 5′ splice site has the canonical metazoan consensus sequence AG/GURAGU (exon/intron), and most 3′ splice sites have a conserved sequence UUUUCAG/R (intron/exon). Despite the sequence conservation, a few studies show that mRNA splicing in C. elegans does not have stringent requirement for the CAG at the 3′ splice acceptor site, especially when the intron is short (Aroian et al. 1993; Zhang and Blumenthal 1996). A study demonstrated that an intron of 48 bp, which is a typical length in C. elegans, can be spliced out in the normal position despite mutations in the splice acceptor site, while longer introns (171 and 283 bp) are more dependent on canonical sequences at splice sites (Zhang and Blumenthal 1996). However, the mechanism of how accuracy of mRNA splicing is maintained for compromised or noncanonical splice sites still remains poorly understood. Our analysis of the splice acceptor mutation dlk-1(ju600) has added to our understanding of the mechanisms that ensure the fidelity of splice site selection. Intron 3 of dlk-1 and intron 1 of dpy-10 are 46 bp and 48 bp, respectively, and contain CAG at the 3′ splice site, which are mutated to CAA in dlk-1(ju600) and dpy-10(e128). Our RT-PCR and qRT-PCR data indicate that these mutated introns can be properly spliced in the mutant animals, consistent with predictions from previous studies (Zhang and Blumenthal 1996). Although loss of function in ess-2 does not alter this splicing step in wild type, it led to strongly impaired splicing in dlk-1(ju600) and dpy-10(e128). Moreover, the dependency of dlk-1(ju600) on ess-2(lf) to suppress rpm-1(lf) provides functional evidence for the altered splicing. Together, these data support the role of ESS-2 in ensuring accurate mRNA splicing when the splice site is compromised and relies on noncanonical sequences.

mRNA splicing generally consists of two catalytic events, lariat intermediate formation in an intron and ligation of the two exons. In each step, splicing factors and snRNA components are dynamically exchanged and rearranged (Morton and Blumenthal 2011; Hegele et al. 2012). Among them the ribonucleoprotein complex that catalyzes the ligation step is called the C complex in which snRNAs and most proteins are conserved in C. elegans (Morton and Blumenthal 2011) (data not shown). The mammalian ES2/DGCR14 was found to coprecipitate with the C complex (Hegele et al. 2012), suggesting that ESS-2 may be functioning in the C complex in C. elegans. We found that both fully spliced and unspliced transcripts appeared to be reduced in dlk-1(ju600); ess-2(ju1117) mutants, although the amount of transcripts was not changed. ess-2(lf) might cause intron 3 of dlk-1(ju600) transcripts to be stalled as a lariat structure, which might not be detected by RT-PCR and qRT-PCR. Further studies may address the precise effects of ESS-2 and its associated proteins in mRNA splicing. We observed similar effects on a dpy-10 splice acceptor mutant, suggesting that ESS-2 function in splicing is widespread. We did not find any obvious phenotype nor splice deficiency in ess-2 single mutant. This suggests that ESS-2 may play a redundant role with another component in C complex, or an accessory role in ensuring accurate splicing. As ESS-2 is a conserved protein from yeast to human, this mechanism ensuring accurate splicing may be conserved in higher organisms.

The fission yeast ortholog of ES2, Bis1, was found as an interacting protein to a stress-response nuclear envelope protein Ish1 (induced in stationary phase 1) and plays a role in viability in the stationary phase (Taricani et al. 2002). Human ES2/DGCR14 is highly expressed in heart, brain, and skeletal muscle and is located in the common chromosome region on 22q11.2 deleted in patients with DiGeorge syndrome and velocardiofacial syndrome (Lindsay et al. 1996; Rizzu et al. 1996; Gong et al. 1997). Although these syndromes have been attributed to disruption of the T-box transcription factor, Tbx1, based on knockout studies in mice (Jerome and Papaioannou 2001; Lindsay et al. 2001; Merscher et al. 2001), it remains possible that deletion of ES2/DGCR14 may contribute to pathological progress in human patients through impaired splicing. Indeed, an analysis of point mutations associated with multiple human genetic diseases has estimated that up to 15% of all these mutations may result in mRNA splicing defects (Krawczak et al. 1992). Moreover, a recent study has suggested that promoter polymorphisms in the ES2/DGCR14 gene are associated with schizophrenia (Wang et al. 2006). Thus, examining in vivo targets of ESS-2 in the future will aid in better understanding the physiological roles of the ESS-2 family of proteins in higher organisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Mei Zhen and Xun Huang for their contribution in the early studies of synergistic interactions between rpm-1 and syd-1 or syd-2 genes. We thank Gloriana Trujillo, Dong Yan, and Neset Ozel for noting the complex genetic traits of dlk-1(ju600); past and present members of our laboratory for discussion and advice; and Andrew Chisholm for critical comments on the manuscript. We thank Shohei Mitani and the National Bioresearch Project (Tokyo Women’s Medical University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan) and C. elegans knockout consortium for providing deletion alleles, Navin Pokala and Cornelia Bargmann for providing the code for the multiworm tracker prior to publication, and Seika Takayanagi-Kiya for her help in tracking analysis. Some of the strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH)–National Center for Research Resources. This work was supported by a grant from NIH to Y.J. (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke R01-035546). K.N. and A.G. are research associates and Y.J. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.114.167841/-/DC1.

Communicating editor: M. Sundaram

Literature Cited

- Ackley B. D., Jin Y., 2004. Genetic analysis of synaptic target recognition and assembly. Trends Neurosci. 27: 540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian R. V., Levy A. D., Koga M., Ohshima Y., Kramer J. M., et al. , 1993. Splicing in Caenorhabditis elegans does not require an AG at the 3′ splice acceptor site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 626–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow H., Doitsidou M., Sarin S., Hobert O., 2009. MAQGene: software to facilitate C. elegans mutant genome sequence analysis. Nat. Methods 6: 549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bounoutas A., Kratz J., Emtage L., Ma C., Nguyen K. C., et al. , 2011. Microtubule depolymerization in Caenorhabditis elegans touch receptor neurons reduces gene expression through a p38 MAPK pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 3982–3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch’ng Q., Williams L., Lie Y. S., Sym M., Whangbo J., et al. , 2003. Identification of genes that regulate a left-right asymmetric neuronal migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 164: 1355–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y., Taru H., Deken S. L., Grill B., Ackley B., et al. , 2006. SYD-2 Liprin-[alpha] organizes presynaptic active zone formation through ELKS. Nat. Neurosci. 9: 1479–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorenzi M., Speed T., 2002. An HMM model for coiled-coil domains and a comparison with PSSM-based predictions. Bioinformatics 18: 617–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadi M., Sleigh J. N., Walker A., Chang H. C., Sen A., et al. , 2010. Conserved genes act as modifiers of invertebrate SMN loss of function defects. PLoS Genet 6: e1001172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W., Emanuel B. S., Galili N., Kim D. H., Roe B., et al. , 1997. Structural and mutational analysis of a conserved gene (DGSI) from the minimal DiGeorge syndrome critical region. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6: 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall D. H., Hedgecock E. M., 1991. Kinesin-related gene unc-104 is required for axonal transport of synaptic vesicles in C. elegans. Cell 65: 837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam S. J., Jin Y., 1998. lin-14 regulates the timing of synaptic remodelling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 395: 78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam S. J., Goncharov A., McEwen J., Baran R., Jin Y., 2002. SYD-1, a presynaptic protein with PDZ, C2 and rhoGAP-like domains, specifies axon identity in C. elegans. Nat. Neurosci. 5: 1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegele A., Kamburov A., Grossmann A., Sourlis C., Wowro S., et al. , 2012. Dynamic protein-protein interaction wiring of the human spliceosome. Mol. Cell 45: 567–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerome L. A., Papaioannou V. E., 2001. DiGeorge syndrome phenotype in mice mutant for the T-box gene, Tbx1. Nat. Genet. 27: 286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y., 2005 Synaptogenesis (December 23, 2005), WormBook, ed. The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook, /10.1895/wormbook.1.44.1, http://www.wormbook.org.

- Jin Y., Garner C. C., 2008. Molecular mechanisms of presynaptic differentiation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 24: 237–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczak M., Reiss J., Cooper D. N., 1992. The mutational spectrum of single base-pair substitutions in mRNA splice junctions of human genes: causes and consequences. Hum. Genet. 90: 41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao E. H., Hung W., Abrams B., Zhen M., 2004. An SCF-like ubiquitin ligase complex that controls presynaptic differentiation. Nature 430: 345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay E. A., Rizzu P., Antonacci R., Jurecic V., Delmas-Mata J., et al. , 1996. A transcription map in the CATCH22 critical region: identification, mapping, and ordering of four novel transcripts expressed in heart. Genomics 32: 104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay E. A., Harvey E. L., Scambler P. J., Baldini A., 1998. ES2, a gene deleted in DiGeorge syndrome, encodes a nuclear protein and is expressed during early mouse development, where it shares an expression domain with a Goosecoid-like gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7: 629–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay E. A., Vitelli F., Su H., Morishima M., Huynh T., et al. , 2001. Tbx1 haploinsufficieny in the DiGeorge syndrome region causes aortic arch defects in mice. Nature 410: 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeder C. I., Shen K., 2011. Genetic dissection of synaptic specificity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 21: 93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C. C., Kramer J. M., Stinchcomb D., Ambros V., 1991. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 10: 3959–3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merscher S., Funke B., Epstein J. A., Heyer J., Puech A., et al. , 2001. TBX1 is responsible for cardiovascular defects in velo-cardio-facial/DiGeorge syndrome. Cell 104: 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton J. J., Blumenthal T., 2011. RNA processing in C. elegans. Methods Cell Biol. 106: 187–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata K., Abrams B., Grill B., Goncharov A., Huang X., et al. , 2005. Regulation of a DLK-1 and p38 MAP kinase pathway by the ubiquitin ligase RPM-1 is required for presynaptic development. Cell 120: 407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nix P., Hisamoto N., Matsumoto K., Bastiani M., 2011. Axon regeneration requires coordinate activation of p38 and JNK MAPK pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 10738–10743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou C. Y., Shen K., 2010. Setting up presynaptic structures at specific positions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 20: 489–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M. R., Shen K., 2009. RSY-1 is a local inhibitor of presynaptic assembly in C. elegans. Science 323: 1500–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei D. Q., Shih C. H., 1991. An “attenuator domain” is sandwiched by two distinct transactivation domains in the transcription factor C/EBP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11: 1480–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokala N., Liu Q., Gordus A., Bargmann C. I., 2014. Inducible and titratable silencing of Caenorhabditis elegans neurons in vivo with histamine-gated chloride channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: 2770–2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock D. D., Larkin J. C., 2004. Estimating the degree of saturation in mutant screens. Genetics 168: 489–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzu P., Lindsay E. A., Taylor C., O’Donnell H., Levy A., et al. , 1996. Cloning and comparative mapping of a gene from the commonly deleted region of DiGeorge and Velocardiofacial syndromes conserved in C. elegans. Mamm. Genome 7: 639–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman J. H., Singson A., 2011. Caenorhabditis elegans: molecular genetics and development. Methods Cell Biol. 106: xv–xviii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi A., Matsumoto K., Hisamoto N., 2004. Roles of MAP kinase cascades in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biochem. 136: 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A. M., Hadwiger G. D., Nonet M. L., 2000. rpm-1, a conserved neuronal gene that regulates targeting and synaptogenesis in C. elegans. Neuron 26: 345–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhof T. C., 2012. The presynaptic active zone. Neuron 75: 11–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taricani L., Tejada M. L., Young P. G., 2002. The fission yeast ES2 homologue, Bis1, interacts with the Ish1 stress-responsive nuclear envelope protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 10562–10572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo G., Nakata K., Yan D., Maruyama I. N., Jin Y., 2010. A ubiquitin E2 variant protein acts in axon termination and synaptogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 186: 135–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Duan S., Du J., Li X., Xu Y., et al. , 2006. Transmission disequilibrium test provides evidence of association between promoter polymorphisms in 22q11 gene DGCR14 and schizophrenia. J. Neural Transm. 113: 1551–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterston R. H., Brenner S., 1978. A suppressor mutation in the nematode acting on specific alleles of many genes. Nature 275: 715–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. G., Southgate E., Thomson J. N., Brenner S., 1986. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 314: 1–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. C., Baer M., Dillner A. J., Johnson P. F., 1995. CRP2 (C/EBP beta) contains a bipartite regulatory domain that controls transcriptional activation, DNA binding and cell specificity. EMBO J. 14: 3170–3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills N., Gesteland R. F., Karn J., Barnett L., Bolten S., et al. , 1983. The genes sup-7 X and sup-5 III of C. elegans suppress amber nonsense mutations via altered transfer RNA. Cell 33: 575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D., Jin Y., 2012. Regulation of DLK-1 kinase activity by calcium-mediated dissociation from an inhibitory isoform. Neuron 76: 534–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D., Wu Z., Chisholm A. D., Jin Y., 2009. The DLK-1 kinase promotes mRNA stability and local translation in C. elegans synapses and axon regeneration. Cell 138: 1005–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D., Noma K., Jin Y., 2011. Expanding views of presynaptic terminals: new findings from Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 22: 431–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Blumenthal T., 1996. Functional analysis of an intron 3′ splice site in Caenorhabditis elegans. RNA 2: 380–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen M., Jin Y., 1999. The liprin protein SYD-2 regulates the differentiation of presynaptic termini in C. elegans. Nature 401: 371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen M., Huang X., Bamber B., Jin Y., 2000. Regulation of presynaptic terminal organization by C. elegans RPM-1, a putative guanine nucleotide exchanger with a RING-H2 finger domain. Neuron 26: 331–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.