Abstract

Although there is marked variation in how people cope with interpersonal loss, there is growing recognition that most people manage this extremely stressful experience with minimal to no impact on their daily functioning (G. A. Bonanno, 2004). What gives rise to this resilient capacity? In this paper, we provide an operational definition of resilience as a specific trajectory of psychological outcome and describe how the resilient trajectory differs from other trajectories of response to loss. We review recent data on individual differences in resilience to loss, including self-enhancing biases, repressive coping, a priori beliefs, identity continuity and complexity, dismissive attachment, positive emotions, and comfort from positive memories. We integrate these individual differences in a hypothesized model of resilience, focusing on their role in appraisal processes and the use of social resources. We conclude by considering potential cultural constraints on resilience and future research directions.

It’s evident the art of losing’s not too hard to master though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

—Elizabeth Bishop

People we are close to die. This is an unfortunate but inevitable fact of life virtually all of us must face. Despite the near universality of this experience, it has long been assumed that bereavement almost always results in significant and sometimes incapacitating distress. Indeed, the absence of distress after loss has in itself been considered pathological and a likely harbinger of future difficulties (Middleton, Moylan, Raphael, Burnett, & Martinek, 1993). Persons who fail to display the expected distress reaction were considered to be suppressing their grief (Middleton, et al., 1993) or to lack an attachment to their spouse (Fraley & Shaver, 1999). Alternately, healthy adjustment to loss was often ascribed to exceptional strength and thus thought to be relatively rare. In stark contrast to these extreme views, a growing body of research now demonstrates that most bereaved persons display stable, healthy levels of psychological and physical functioning as well as the capacity for generative experiences and positive emotions even relatively soon after a loss (Bonanno, 2004).

A large number of contextual and situational factors potentially contribute to the likelihood of a resilient outcome (Bonanno & Mancini, 2008). These include characteristics of the loss and the person’s environment. However, our primary concern in this article is person-centered factors or individual differences. Because of the dearth of prospective studies of bereavement, our understanding of these factors is still evolving. Nevertheless, convergent evidence has now identified a number of individual difference variables that are associated with a resilient trajectory. These include self-enhancing biases, attachment style, repressive coping, a priori beliefs, identity continuity and complexity, and positive emotions (Bonanno, Field, Kovacevic, & Kaltman, 2002; Fraley & Bonanno, 2004; Keltner & Bonanno, 1997). These factors may interact with one another and with environmental factors in complex ways that we are only beginning to understand. Surprisingly, some factors that promote resilience to loss may be maladaptive in other contexts, whereas other factors are more broadly adaptive. In this paper, we first provide an operational definition of resilience and describe how it differs from other trajectories of response to loss. We describe evidence for its prevalence and for the heterogeneous individual differences associated with resilience. We then integrate these individual differences into a proposed model of resilience, considering shared mechanisms related to appraisal processes, coping strategies, and the use of exogenous resources, such as social support.

DEFINING RESILIENCE TO LOSS

Although people may possess characteristics associated with resilience, whether people actually exhibit resilience can only be defined in terms of their level of adjustment after the stressor event. Resilience cannot be defined in the abstract or applied to individuals in the absence of an extremely aversive experience, such as loss. Thus, it is uninformative, if not meaningless in this framework, to describe someone as having a resilient personality, because resilience is defined ex post facto. Indeed, the psychological study of resilience mandates that we operationally define resilience as an outcome following a highly stressful event and then document the factors that appear to promote or detract from that outcome.

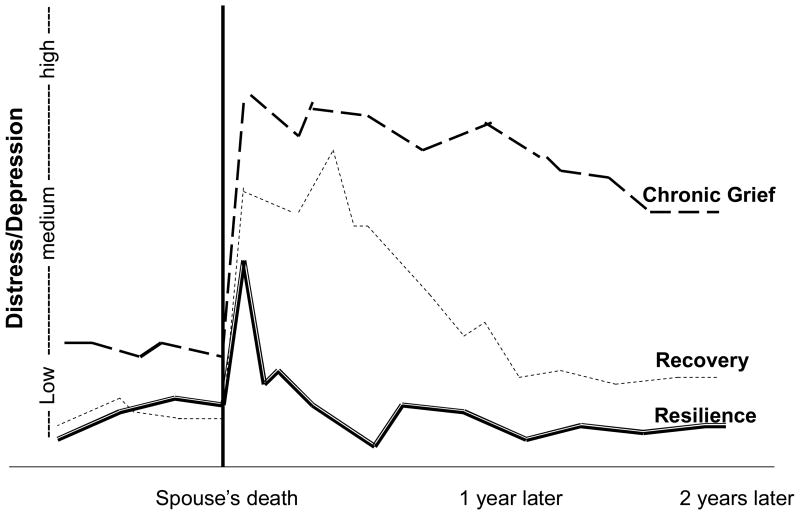

Another critical point is that resilience can be reliably distinguished from the two other most prevalent patterns following loss: chronic dysfunction (acute, persistent, and disabling symptoms) and recovery (acute symptoms that gradually subside; Bonanno, 2004). These trajectories are illustrated graphically in Figure 1. It can be readily observed that resilience and chronic dysfunction are markedly different reactions, but the distinction between resilience and recovery is more subtle and has only recently been firmly established. An initial study focused on how people coped with the premature death of a spouse at midlife (Bonanno, Keltner, Holen, & Horowitz, 1995). Although using relatively small samples, this study demonstrated that a stable pattern of low distress over time, or resilience, could be clearly distinguished from the more conventionally understood pattern of recovery. That is, bereaved persons who exhibit the recovery pattern struggle with moderate levels of symptoms and experience difficulties carrying out their normal tasks at work or in the care of loved ones, but they somehow manage to struggle through these tasks and slowly begin to return to their preloss level of functioning, usually over a period of 1 or 2 years. By contrast, persons who exhibit resilience seem to be able to go on with their lives with minimal or no apparent disruptions in functioning.

Figure 1.

Prototypical patterns of disruption in normal functioning across time after bereavement. Reproduced with permission from Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59, 20–28.

More recent studies have provided additional evidence for the distinction between resilience and recovery using samples involving different types of loss. For example, Bonanno, Moskowitz, Papa, and Folkman (2005) identified these trajectories in samples of bereaved parents, bereaved spouses, and bereaved gay men. They also obtained anonymous ratings of participants’ adjustment from their close friends and showed that resilient individuals were rated by their friends as better adjusted prior to the loss than more symptomatic bereaved individuals and than a comparable sample of nonbereaved (i.e., married) people.

We would emphasize that the resilient pattern does not imply that such persons experience no upset related to the loss or aversive event, but rather that their overall level of functioning is essentially preserved. For example, in a sample of bereaved individuals who were followed from several years prior to the death of their spouse to several years afterwards, almost half showed no clinical depression at any point in the study (Bonanno, Wortman, et al., 2002). However, when questioned about their experiences soon after the loss, about 75% of those showing a resilient outcome trajectory reported experiencing intense yearning (painful waves of missing spouse) as well as pangs of intense grief at some point in the earliest months of bereavement. What is more, all but one of the bereaved people showing the resilient trajectory reported having experienced intrusive and unbidden thoughts about the loss that they could not get out of their mind and that they found themselves ruminating about or going over and over what happened when the spouse died in the earliest months of bereavement. The key difference here is that resilient individuals are able to manage these difficult experiences in such a manner that they do not interfere with their ability to maintain functioning.

THE PREVALENCE OF RESILIENCE

The bereavement literature has long provided evidence that bereaved persons do sometimes show a striking absence of dysfunction, though only recently has this been viewed as evidence for resilience. For example, researchers in one earlier study examined a number of different grief symptoms and reactions using survey data from 350 widows and widowers (Zisook & Shuchter, 1993). At 2 months after the loss, 70% of their sample reported that they found it “hard to believe” that their spouses had actually died. However, more extreme cognitive difficulties were only exhibited by a considerably smaller portion of the sample. Even in the earliest point of bereavement, 2 months after the death of their spouse, only about one fifth or fewer of the bereaved participants reported that they had difficulties concentrating (20%) or making decisions (17%). Furthermore, 76% of bereaved persons failed to meet criteria for major depression at 2 months and 86% at 25 months postloss. Again, although these data indicate that many bereaved people struggle with disruptions in their functioning in the first months after a loss, a substantial proportion do not, providing evidence for resilience to loss.

More recent and compelling evidence for the prevalence of resilience came from the Changing Lives of Older Couples (CLOC) study, a study of spousal bereavement in late life (Mancini, Pressman, & Bonanno, 2006). The resilient bereaved in this study comprised 46% of the sample and showed little or no depression at each assessment point in the study, beginning on average 3 years prior to the death of a spouse and continuing through 18 months after the spouse’s death (Bonanno, Wortman, et al., 2002). Resilient participants also exhibited few grief symptoms (e.g., yearning) during bereavement. What is more, the prevalence of resilience remained relatively constant regardless of whether the trajectory was defined by the simple absence of change from pre- to postbereavement or by more emergent statistical approaches, such as hierarchical cluster analysis, nonlinear mixed model analysis, or latent class analyses (Burke, Shrout, & Bolger, 2007; Mancini & Bonanno, 2008b). Additional evidence for the prevalence of resilience came from research mentioned earlier on bereaved spouses, bereaved parents, and bereaved gay men (Bonanno, Moskowitz, et al., 2005). Using normative comparisons to nonbereaved persons, this study showed that resilience was evidenced in at least half of bereaved persons across both samples.

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES ASSOCIATED WITH RESILIENCE TO LOSS

Why are some people able to move on with their lives and maintain their levels of functioning relatively soon after the loss, whereas others struggle to a greater extent and, in some cases, become mired in debilitating feelings of yearning and emptiness? In other words, what factors contribute to the likelihood of a resilient response to loss? In addition to the many situational and contextual factors, it appears that there are at least two different styles of coping that predict a resilient outcome. Elsewhere we have labeled these flexible adaptation and pragmatic coping (Bonanno, 2005; Bonanno & Mancini, 2008; Mancini & Bonanno, 2006). The idea of pragmatic coping stems from the fact that stressful life events, like the death of a spouse, often pose highly specific coping demands. Successfully meeting these demands may require a highly pragmatic or “whatever it takes” approach that is single minded and goal directed. Although pragmatic coping can arise in response to the situational demands, it has also been observed as a consequence of relatively rigid personality characteristics, such as repressive coping, dismissive attachment, and the habitual use of self-enhancing attributions and biases. A compelling finding with these pragmatic styles is that, although they have been associated with some negative features (e.g., narcissism, health consequences), they consistently predict superior adjustment to loss and other potentially traumatic life events.

We stress however, that most people capable of resilience to adversity are genuinely healthy people who appear to possess a capacity for behavioral elasticity or flexible adaptation to impinging challenges. The hallmark of this characteristic is the capacity to shape and adapt behavior to the demands of a given stressor event. A number of individual differences may contribute to this kind of flexible adaptatation. For example, resilience to loss has also been associated with more favorable preexisting beliefs (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Tomaka & Blascovich, 1994), positive emotions (Bonanno & Keltner, 1997), and the ability to derive comfort from positive memories (Bonanno, Wortman, & Nesse, 2004). Next we consider in turn these individual difference variables.

Repressive Coping

A perhaps unlikely source of resilience is found among persons who habitually employ coping mechanisms designed to repress negative affects. Repressive coping is marked by simultaneous avoidance of threatening or negative stimuli and increased physiological arousal in response to that stimuli (e.g. Bonanno & Singer, 1990; Hock & Krohne, 2004; Tomarken & Davidson, 1994). Under stressful circumstances, repressive copers tend to report minimal or no feelings of distress but physiological measures reveal marked autonomic arousal (Weinberger, Schwartz, & Davidson, 1979). This kind of dissociation from one’s emotions or internal states has historically been seen as maladaptive (Bowlby, 1980; Osterweis, Solomon, & Green, 1984), and may be associated with long-term health costs (Bonanno & Singer, 1990; King, Taylor, Albright, & Haskell, 1990). However, a growing literature has linked these same tendencies to adaptation to loss and to other forms of adversity. For example, repressors tend to show relatively little grief or distress at any point across 5 years of bereavement, a pattern consistent with resilience (Bonanno & Field, 2001; Bonanno et al., 1995). More recent work has shown that repressive coping in bereaved persons is not only associated with lower symptoms but also fewer reported health problems and higher ratings of adjustment by close friends (Coifman, Bonanno, Ray, & Gross, 2007). Moreover, the benefits of repressive coping are also apparent among nonbereaved controls, suggesting a general adaptive advantage for repressors.

Why would repressive coping facilitate adaptive coping with loss? One important point is that repressive coping is largely an automatic process in which the person effortlessly orients away from threatening stimuli (Bonanno, Davis, Singer, & Schwartz, 1991). Thus, repressive coping is distinct from more conscious and effortful strategies to manage aversive thoughts and feelings, such as thought suppression or deliberate cognitive avoidance (Bonanno et al., 1995). Largely because it requires significant cognitive resources, suppression has been associated with a variety of untoward consequences in interpersonal, physiological, and emotional functioning (Gross & John, 2003; Gross & Levenson, 1993, 1997). By contrast, repressive coping appears to mitigate the potentially overwhelming and threatening nature of aversive experiences without exacting a cost in cognitive resources. By easing the threatening nature of their experience, repressors may be more likely to employ active problem-focused coping rather than passive emotion-focused coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Olff, Langeland, & Gersons, 2005), which would be particularly ineffective in the context of bereavement. Indeed, when confronted with highly threatening stimuli, repressors report more active rather than passive coping strategies (Langens & Moerth, 2003).

Attachment Dynamics

Another factor that appears to contribute to resilience to loss is attachment dynamics, which describes the impact of early caregiving experiences on adult relationships. Bowlby’s (1980) early theorizing first established attachment theory as a basic explanatory framework for understanding how people cope with loss. Since that time, a prime focus of bereavement theorists has been the degree to which avoidance characterizes a person’s relationships with others. This avoidance component is usually conceptualized within a two-dimensional model contrasting attachment-related preoccupation or anxiety with the dismissive characteristics associated with attachment avoidance (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Fraley & Shaver, 2000). People who are high on attachment-related avoidance tend to minimize interpersonal intimacy and to withdraw from close others, whereas those who are low on this dimension tend to feel more comfortable relying on others (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). By contrast, people with high levels of attachment-related anxiety are intensely concerned with maintaining proximity to and ensuring the availability of close others, whereas people low on this dimension are able to trust in the availability and responsiveness of others (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Persons low on both dimensions are generally thought to be securely attached.

Early speculations on the role of attachment dynamics in coping with loss postulated that avoidant attachment would be associated with less pronounced grief symptoms and distress soon after the loss (Bowlby, 1980) but also that avoidant individuals would be at substantial risk for subsequent difficulties, a hypothesized “delayed” pattern of grief (Middleton et al., 1993). Despite numerous investigations of this question, no solid evidence has been proffered for delayed grief (Bonanno & Field, 2001). As the notion of delayed grief has increasingly vanished in the mist, a more nuanced understanding of the role of attachment avoidance has begun to take its place. In this regard, it is important to note that the two-dimensional conceptualization of attachment permits the derivation of four distinct patterns of attachment, which correspond to whether the person is high or low on anxiety and avoidance. A critical distinction to consider is between dismissing avoidance (high avoidance, low anxiety) and fearful avoidance (high avoidance, high anxiety; Fraley, Davis, & Shaver, 1998). Dismissingly avoidant persons are generally not preoccupied with attachment concerns and view themselves as independent and self-reliant, whereas those who are fearfully avoidant tend to use avoidance as a way of quelling intense anxiety about relationships with close others. If this distinction is not made, avoidant individuals can appear to have coping deficits, because dismissing avoidance is conflated with fearful avoidance (Fraley et al., 1998). Consistent with the more nuanced perspective, Fraley and Bonanno (2004) found clear evidence for the adaptive benefits of dismissing avoidance in a recent longitudinal study of bereaved spouses and parents. Specifically, bereaved persons with a dismissing avoidant attachment pattern had relatively few symptoms across bereavement and showed a similar trajectory over time as did persons with a secure attachment style (low avoidance, low anxiety). By contrast, fearful avoidant individuals had elevated grief symptoms across time.

Does the quality of the relationship to the deceased moderate the impact of attachment style on distress after loss? This issue could be particularly pertinent to spousal loss, because of the potential variation in the degree to which the deceased spouse served as a central attachment figure to the bereaved person (Cassidy & Shaver, 1999). In distressed marriages, for example, the attachment functions served by the spouse would be likely to be far more circumscribed than in nondistressed marriages. For this reason, it is possible that the negative effects of anxious attachment are only present in the context of high levels of marital satisfaction, which would presumably indicate that the deceased served important attachment functions. Furthermore, it is also possible that attachment avoidance, in the context of a positive marital relationship, would facilitate the bereaved person’s separation from the deceased and thus contribute to a more resilient response to loss.

In a recent longitudinal study of bereaved spouses, we found evidence to support each of these perspectives (Mancini, Robinaugh, Shear, & Bonanno, 2008). First, attachment anxiety was predictive of increased symptoms of bereavement-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from 4 to 18 months postloss, but this effect was observed primarily among participants who reported a positive marital relationship. The opposite pattern was observed for attachment avoidance. High avoidance individuals who had a favorable marital relationship tended to experience reductions in PTSD from 4 to 18 months.

Self-Enhancing Biases

Another contributing factor to the likelihood of a resilient outcome in response to loss is trait self-enhancement. Historically, a positive view of the self has been viewed as a basic component of health and well-being, but only when coupled with a realistic appreciation of one’s personal limitations and negative characteristics (Allport, 1937; Erikson, 1950; Maslow, 1950; Vaillant, 1977). However, research has demonstrated that a dispositional tendency to view the self in highly favorable and even unrealistic terms (trait self-enhancement) is often associated with psychological adjustment (Taylor & Brown, 1988, 1994). Moreover, although there is also evidence that self-enhancement is associated with real social costs (Paulhus, 1998), self-enhancers appear to cope particularly well with extreme adversity (Bonanno, Field, et al., 2002; Bonanno, Rennicke, & Dekel, 2005; Taylor & Armor, 1996). These benefits were revealed in a study examining traumatic and nontraumatic spousal loss (Bonanno, Field, et al., 2002). In two studies, self-enhancement predicted lower grief symptoms at multiple intervals across bereavement and using different assessments of symptoms.

How does self-enhancement facilitate coping and promote resilience to loss? Because the aversive experience of loss represents a potential threat to the self and may induce feelings of vulnerability and weakness, bereaved persons are likely motivated to restore their sense of control over the event and their sense of optimism about the future (Taylor & Armor, 1996). Self-enhancing cognitions could facilitate this process, through downward social comparisons to others who are less fortunate (Helgeson & Taylor, 1993) or through reframing the aversive experience as providing unexpected benefits (Taylor, Wood, & Lichtman, 1983). Moreover, although self-enhancement can entail social liabilities, it also may play a role in whether the bereaved person draws effectively on social supports and has opportunities to disclose thoughts and feelings related to the event. An ample literature has shown the beneficial effects of self-disclosure after one experiences an acute stressor (Lepore, Silver, Wortman, & Wayment, 1996). Consistent with this notion, a previous study of high-exposure survivors of the 9/11 attacks found that self-enhancement’s beneficial effects on coping are mediated by perceived constraints against disclosing distressing experiences (Bonanno, Rennicke, et al., 2005). Indeed, the beneficial effects of self-disclosure appear to depend on whether social resources are perceived as available and interested in hearing one’s concerns. To the degree that others are perceived as unwilling or unavailable, the beneficial effects of self-disclosure are obviated (e.g., Lepore, Ragan, & Jones, 2000). Interestingly, self-enhancers are particularly likely to view their friends as willing and able to listen to their deepest worries and concerns, even if this perception is at odds with friends’ actual behavior (Goorin & Bonanno, 2008).

Worldviews (a Priori Beliefs)

A more broadly beneficial component of resilience to loss is favorable a priori beliefs or worldviews, which comprise our most abstract and generalized conceptions of the degree that life is just, fair, predictable, and benevolent (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Park & Folkman, 1997; Rubin & Peplau, 1975). Because worldview beliefs may be influenced by the impact of loss or other stressful events (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Schwartzberg & Janoff-Bulman, 1991), it has historically been difficult to untangle their effects on coping. The only methodological solution to this difficulty is to employ a prospective design that includes preloss measures of worldviews. To our knowledge, the only study to meet this condition was the CLOC study, described earlier, which obtained baseline data from a representative sample of older couples and married individuals and then invited persons who subsequently suffered a loss to participate in follow-up interviews at 6 and 18 months of bereavement. Using these data to map trajectories of bereavement outcome, Bonanno, Wortman, et al. (2002) identified four primary trajectories (resilience, recovery, chronic grief, and chronic depression), each associated with unique predictors.

Among the preloss predictors of resilience were stronger beliefs in the world’s justice and more accepting attitudes toward death. We recently provided additional confirmation for the role of a priori beliefs by showing that favorable worldviews were related to adjustment over time only among bereaved persons and not among nonbereaved controls (Mancini & Bonanno, 2008a). Together, these findings indicated that more positive beliefs in a just world and greater acceptance of death may help bereaved persons accommodate the reality of the loss into their existing worldviews, blunting the potentially threatening nature of loss. In addition, it may well be the case that more benign beliefs about death would be of particular adaptive significance in the context of loss, because such beliefs could ease the potentially deleterious effects of death anxiety so widely demonstrated by terror management theorists (e.g., Pyszczynski, Greenberg, Solomon, Arndt, & Schimel, 2004).

Do favorable worldviews, when measured after the loss, enhance the likelihood of resilience? A recent investigation indicates that, in the main, they do not (Mancini & Bonanno, 2008a). Although beliefs in the world’s benevolence and self-worth showed cross-sectional relationships with grief and PTSD at 4 and 18 months postloss (Mancini & Bonanno, 2008a), only beliefs about the self at 4 months predicted later symptoms at 18 months after controlling for 4-month symptoms. This suggests that negative worldviews are an associated feature of more serious grief reactions but do not serve to maintain grief reactions or to further resilient responses to loss. Rather, available evidence suggests that a priori beliefs primarily operate on initial appraisals of the experience of loss. After factoring in their effects on initial coping and grief reactions, a priori beliefs do not appear to exert further incremental effects (Mancini & Bonanno, 2008a).

Nevertheless, it is clear that initial appraisals have a substantial impact on coping in response to stressors (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Park & Folkman, 1997). A critical issue is whether the stressor is seen as challenging (within one’s ability to cope) or threatening (exceeding one’s ability to cope; e.g., Tomaka, Blascovich, Kelsey, & Leitten, 1993). It would appear that bereaved persons with more favorable preloss worldviews would be able to understand the loss as a specific negative event and would be less likely to overgeneralize to broader notions of the world and the self. In this way, the potentially threatening nature of bereavement would be mitigated. By contrast, for persons with more negative preloss worldviews, the experience of loss might confirm that worldview and enhance a feeling that events are out of one’s control and beyond one’s ability to manage. Such appraisals influence the coping strategies used to manage stressful situations and thus determine their effectiveness (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). For example, more threatening appraisals of stressors are associated with more negative emotion, greater physiological reactivity (Tomaka et al., 1993), and less adaptive neuroendocrine functioning (Epel, McEwen, & Ickovics, 1998). As a result, appraisals of threat may lead to an excessive reliance on short-term emotion-focused coping strategies and a corresponding neglect of problem-focused coping (Olff et al., 2005). Over time, these coping deficits may have particularly deleterious effects in the context of bereavement, a complex stressor that requires a range of strategies for effective coping.

Identity Continuity and Complexity

Views of the self are another factor that appear to influence coping and are associated with resilience to loss (Mancini & Bonanno, 2006). The emotional upheaval surrounding the loss of a loved one may be particularly damaging to a person’s underlying sense of identity. Familiar routines or rituals are often disrupted, and social roles may be dramatically changed. Persons with the most serious forms of grief sometimes report that they feel as if a piece of them is missing, as if the self is incomplete (Shuchter & Zisook, 1993). Similarly, traumatized individuals commonly experience the self as damaged or inferior (Brewin, 2003). By contrast, resilient individuals appear to experience minimal change in their sense of themselves (Bonanno, Papa, & O’Neill, 2001). We have argued that resilient persons seem to experience an underlying continuity in the self and, armed with that continuity, are better able to respond flexibly to the demands of a changed world (Mancini & Bonanno, 2006).

This perspective found clear support in a recent preliminary longitudinal study in which bereaved individuals and nonbereaved controls participated in a collaborative task designed to elicit the identity traits that they use to define themselves (Galatzer-Levy, Bonanno, & Mancini, 2008). Participants completed the task with a researcher, who helped them list and clarify their traits (e.g., “kind” or “thoughtful”). Once the list was finalized, the researcher then asked the participant to indicate the extent that each trait had changed since the loss. Resilient individuals reported a relatively low level of identity change (i.e., high identity continuity) at both 4 and 18 months postloss and did not differ from the degree of identity change reported by nonbereaved participants. By contrast, symptomatic bereaved persons experienced significantly greater identity change. Interestingly, the number of traits a person reported, which we defined as identity complexity, was not associated with resilience. However, among more symptomatic bereaved individuals, identity complexity emerged as a meaningful predictor of recovery over time. More specifically, highly depressed bereaved persons who had more complex identities were more likely to recover whereas highly depressed bereaved people with less complex identities tended to have chronically elevated symptoms. Together, these results suggest that identity continuity is primarily a feature of a resilient outcome whereas identity complexity serves as more of a coping factor that is operative at high distress levels.

Positive Emotions

There is growing recognition that positive emotional experiences provide an array of adaptive benefits, both for general functioning and in response to stressful events (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004; but see also Bonanno, Colak, et al., 2007). Countering a once commonly held view that positive emotions in response to loss are a form of unhealthy denial (Bowlby, 1980), evidence now supports the idea that a critical pathway to resilience to loss is through the expression of positive emotions and even laughter (Bonanno & Keltner, 1997; Keltner & Bonanno, 1997). For example, bereaved individuals who exhibited genuine laughs and smiles when speaking about a recent loss had better adjustment over several years of bereavement (Bonanno & Keltner, 1997) and also evoked more favorable responses in observers (Keltner & Bonanno, 1997). Moreover, resilient bereaved people also reported the fewest regrets about their behavior with the spouse or about things they may have done or failed to do when he or she was still alive. Finally, resilient individuals were less likely to search to make sense of or find meaning in the spouse’s death, suggesting that they are less likely to engage in rumination, which has negative consequences for adjustment to loss (Nolen-Hoeksema, McBride, & Larson, 1997).

How do positive emotions facilitate coping with loss? It appears that positive emotional experience can play a role in quieting or undoing negative emotions and thereby reduce levels of distress following loss (Keltner & Bonanno, 1997; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). Furthermore, positive emotions can facilitate coping with loss by increasing the availability of social supports (Bonanno & Keltner, 1997). Positive emotional expression after a loss likely indicates to close others a willingness to maintain pro-social contact (Malatesta, 1990). Indeed, an earlier study found that positive emotional expression was most prevalent among bereaved individuals with higher scores on the socially oriented personality characteristics of extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness (Keltner, 1996). Continued contact with important others in the bereaved person’s social environment can have a variety of salutary consequences (Lepore et al., 1996), especially when one considers that social isolation and loneliness are basic components of more complicated grief reactions (Horowitz et al., 1997).

Comfort from Positive Memories

One final resilience factor is comfort from positive memories of the deceased. Bonanno, Wortman, et al. (2002) found that resilient people are particularly likely to experience positive emotions in tandem with memories of the deceased. Specifically, resilient people were better able than other bereaved participants to gain comfort from talking about or thinking about the spouse. For example, they were more likely than other bereaved people to report that thinking about and talking about their deceased spouse made them feel happy or at peace (Bonanno, Wortman, et al., 2004). Moreover, this capacity remains stable over time for the resilient bereaved, whereas the recovered or chronic grief trajectories show greater variability. For example, persons who demonstrate the recovery pattern see a decline over time in their capacity for comfort from positive memories of the deceased. These findings suggest that comfort from positive memories serves to protect the bereaved person from undue distress related to the loss and to provide a renewable source of positive affect. Seen from an attachment theory perspective, this furthermore suggests that the internalized representation of the deceased continues to serve adaptive ends.

HYPOTHESIZED MODEL OF INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN RESILIENCE

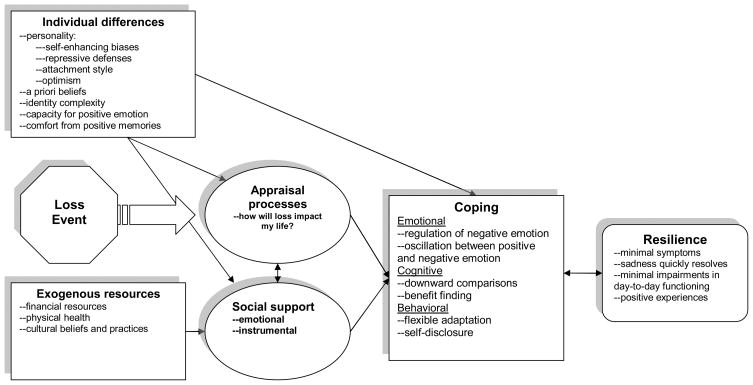

As we noted at the onset of this article and elsewhere (Bonanno, 2004, 2005; Bonanno & Mancini, 2008; Mancini & Bonanno, 2006), the factors associated with resilience are heterogeneous. Indeed, it is increasingly evident that resilience can be achieved through a variety of means. There are multiple risk and protective factors across individuals, and it is the totality of these factors, rather than any one primary factor, that determines the likelihood of a resilient outcome (e.g., Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli, & Vlahov, 2007). Nonetheless, our understanding of resilient processes can be advanced by integrating and organizing these factors along the lines of common or shared mechanisms. These shared mechanisms are graphically illustrated in a hypothesized model of resilience (Figure 2). As can be seen from this diagram, we propose that individual differences have both direct and indirect effects on coping with loss. The indirect effects are channeled through at least two mechanisms of resilience—appraisal processes and social support—each of which can play a salutary role in promoting more effective coping. Next we briefly review evidence to support the critical role of appraisal processes and the use of social resources as shared pathways or mechanisms for resilience.

Figure 2.

Hypothesized model of resilience.

Appraisal Processes

The initial appraisal of the experience of loss plays a critical role in how one copes with it. For example, bereaved persons who view the loss in overwhelming and threatening terms are more likely to employ short-term emotion-focused coping strategies designed to manage distress (Olff et al., 2005). An excessive focus on the regulation of emotions can divert attention from more long-term coping strategies that are problem-focused and ultimately more effective in managing the complex stresses associated with loss. As indicated in Figure 2, a number of individual difference variables have been shown to influence how we appraise loss and other stressful events. For example, self-enhancers appear to benefit from a dispositional tendency to think favorably of the self and to overestimate their ability to control events (Taylor & Armor, 1996). Even if these self-perceptions are inaccurate and even illusory (Goorin & Bonanno, 2008), self-enhancing tendencies can mitigate the degree to which loss and other stressors are perceived as threatening. In a striking demonstration of this, self-enhancers in a laboratory stress paradigm had lower cardiovascular responses to stress and a more rapid cardiovascular recovery, suggestive of adaptive coping (Taylor, Lerner, Sherman, Sage, & McDowell, 2003).

In a somewhat different fashion, persons who employ repressive coping strategies are vulnerable to increases in psychophysiological arousal in the presence of stressors, but also succeed in automatically screening out such stimuli. Although this coping strategy may potentially entail health costs, repressive coping is an effective means of blunting the threatening nature of loss and other stressors. Indeed, repressors appraise laboratory stressors as less threatening than nonrepressors (Tomaka, Blascovich, & Kelsey, 1992). Another factor that may promote a more benign appraisal of loss is favorable a priori beliefs. For example, persons with stronger justice beliefs showed reduced physiological responsiveness in response to threatening stimuli and more adaptive coping responses (Tomaka & Blascovich, 1994; Tomaka et al., 1993). A dismissing–avoidant attachment pattern also may contribute to a more benign appraisal of loss, because such persons tend to value independence and self-reliance and thus would experience loss as less overwhelming. By easing the negative affect associated with the loss, comfort from positive memories would likely also tend to diminish negative appraisals of the loss and of its potential impact. Taken together, these heterogeneous factors appear to share at least one common pathway through which they promote resilience—by mitigating the potentially threatening and overwhelming nature of loss, they promote homeostasis and regulate emotional responses to the loss. They are furthermore likely to increase the availability of positive emotions (Bonanno, Goorin, & Coifman, 2008), which can serve a variety of adaptive functions under stressful conditions (Fredrickson, 1998). Indeed, given that threatening appraisals of stressful events can lead to a host of untoward consequences, including higher reactive levels of cortisol (Buchanan, al’Absi, & Lovallo, 1999), more negative affect (Tomaka et al., 1993; Tomaka, Blascovich, Kibler, & Ernst, 1997), and increased sympathetic arousal (Olff et al., 2005), a critical component of resilience to loss is initial and ongoing appraisals of the event, which set in train a variety of affective and neurobiological consequences that critically shape coping efforts.

Use and Availability of Social Resources

Another common pathway to resilience is the availability and effective use of social resources. For example, although self-enhancers show some social liabilities (Paulhus, 1998), they also have clear strengths in their social functioning. Self-enhancers are more likely to perceive that social resources are supportive (Bonanno, Rennicke, et al., 2005) and are more likely to have larger social networks (Goorin & Bonanno, 2008). As noted above, positive emotional expression is also likely to enhance social resources by indicating a willingness to engage in social interaction (Malatesta, 1990). These social resources would appear to confer a distinct adaptive advantage in coping with loss, increasing the opportunity for beneficial self-disclosure, promoting the regulation of emotion, diminishing isolation, and furthering the development of new social networks. Moreover, as shown in Figure 2, we would argue that supportive social resources and positive appraisals would likely have synergistically ameliorative effects. That is, consistent with the perspective that social interactions can facilitate cognitive integration of stressful experiences (e.g., Lepore et al., 2000), social support would be likely to facilitate less threatening appraisals of the loss. Indeed, social support has been widely shown to buffer the negative effects of stressful events (Cohen & Wills, 1985). By the same token, less threatening appraisals of loss would tend to enhance positive affect and thus broaden the scope of behavior and thought, which in turn would build social resources (Fredrickson, 1998). Broadly consistent with this model, meta-analyses of persons exposed to potentially traumatic events have shown that lack of social support is among the strongest predictors of PTSD (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003).

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

This article has focused on individual difference factors that contribute to resilience to loss. These factors comprise broadly adaptive characteristics, such as positive emotions, favorable beliefs, and identity continuity, and factors that may be more of a mixed blessing, such as repressive coping, dismissive attachment, and the habitual use of self-enhancing attributions and biases. Given the heterogeneity of these resilience factors, it is clear that there are many ways to arrive at a resilient response to loss. Indeed, we argue that resilience is a variegated phenomenon that defies simple characterization. Nevertheless, we suggest that these factors, like tributaries to a river, appear to converge on common mechanisms. Two such mechanisms are appraisal processes and use of social resources. Of course, these resilience factors and mechanisms are neither exhaustive nor definitive. Indeed, future research should seek to identify additional resilience factors, consider the moderating effects of environmental influences, and further refine our understanding of underlying mechanisms of resilience. An additional and important area of study would be to assess the covariation of resilience factors and to identify clusters of individual differences associated with resilience. For example, self-enhancing biases are generally associated with greater levels of positive affect (Robins & Beer, 2001), suggesting an underlying substrate that may impinge on the capacity for resilience. In considering these questions, it is critical for researchers to employ prospective designs, which are the only methodological solution for differentiating grief trajectories and for unconfounding potential resilience factors and the individual’s response to the stressful experience of loss.

What are the implications of the heterogeneous nature of resilience for clinical interventions? One obvious implication is that a variety of coping strategies are effective, and thus a one-size fits all approach for grievers, once commonly endorsed by grief theorists, is no longer tenable. Indeed, the study of resilience suggests a number of potential avenues for clinical intervention (for a longer treatment of this issue, see Mancini & Bonanno, 2006). For example, flexibility in emotion regulation, measured as the ability to either enhance or suppress the expression of emotion in accord with situational demands, predicted better adjustment in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks (Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Westphal, & Coifman, 2004). We are currently exploring how such skills might inform bereavement outcome. Although no formal treatment approach exists to teach these kinds of skills directly, we suspect that coping flexibility might be learned or with practice improved among individuals who lack such abilities. In addition, the critical role of appraisal and social resources suggests intervention strategies. For example, bereaved persons who rely on suppression to regulate feelings—the inhibition of behaviors associated with a specific emotional experience—may impair their ability to absorb information and to function interpersonally (Gross & John, 2003), potentially depriving the person of vital resources. By contrast, cognitive reappraisal, which involves construing a potentially stressful event in benign or growth-oriented terms in order to diminish its emotional impact, may be an important skill in adaptive coping with loss, because it would further emotional regulation while permitting the person to take full advantage of social relationships. Although such techniques are standard components of clinical intervention, given the findings on individual differences in resilience, it seems worth emphasizing their potentially important role in interventions with bereaved persons.

One additional question is the role of contextual factors, such as the nature of the loss, caregiving strain, or material resources, and their potential interaction with individual differences. Although it might appear intuitive that sudden losses would be less likely to be associated with resilience, data have largely been equivocal on this question. However, one well-designed study, using a representative sample, appropriate control variables, and prospective data, found that the sudden loss of a loved one is not, by itself, associated with worse adjustment (Carr, House, Wortman, Neese, & Kessler, 2001). On the other hand, there is evidence that losses from violent causes (suicide, homicide, or violent accident), which are almost always sudden, are associated with more symptomatology and lower levels of resilience (Kaltman & Bonanno, 2003). Interestingly, it appears that self-enhancement offers additional protective effects for such losses. For example, in one study, self-enhancement interacted with traumatic loss (suicide, homicide, or violent accident) to predict lower levels of PTSD primarily among those likely to experience traumatic grief (Bonanno, Field, et al., 2002). Thus, self-enhancement was not only beneficial for coping with ordinary bereavement but also exerted an additional buffering effect on the negative consequences of traumatic deaths. Caregiving strain, by contrast, appears not to be related to resilience per se, but it does predict an unusual trajectory of improved functioning following loss (Bonanno, Wortman, et al. 2002). Additional evidence for the crucial role of contextual factors was found in a recent analysis of a large panel data set. Using a latent class framework, we not only validated the resilient trajectory empirically but we also found that one of the factors associated with resilience was less reduction in income following loss (Mancini & Bonanno, 2008b).

Another question raised by the present review is whether the processes that lead to resilience to loss, a stressor most people are exposed to, are qualitatively different from resilience to other more extreme and violent stressors, such as combat or physical or sexual assault. Extant research suggests that a number of the factors associated with resilience to loss also serve a protective function against these other more extreme stressors. These include self-enhancing biases (Bonanno, Field, et al., 2002; Bonanno, Rennicke, et al., 2005), repressive coping (Bonanno, Noll, Putnam, O’Neill, & Trickett, 2003), and positive emotions (Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh, & Larkin, 2003). Nevertheless, it would appear likely that resilience to loss and to more extreme and violent stressors would have both common and unique predictors. However, research has yet to elucidate the distinctions between these types of resilience.

Although this paper is concerned with individual differences in resilience, a final important question is the role of ethnic and cultural variations in resilience during bereavement. Western, independence-oriented countries tend to focus more heavily than collectivist countries on the personal experience of grief. What are the implications of such cultural beliefs about the self for the study of resilience? Unfortunately, research on the extent to which bereavement reactions might vary across cultures is still nascent. Preliminary evidence suggests that bereaved people in China recover more quickly from loss than do bereaved Americans (Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Nanping, & Noll, 2005). Moreover, for the Chinese, coping is enhanced by a continuing psychological bond with the deceased whereas the evidence for the salutary role of a continuing bond among Americans is less conclusive (Lalande & Bonanno, 2006). These findings suggest that cultural beliefs may even influence the degree to which resilience factors are operative. Moreover, these data raise the question of whether different cultures may learn from each other about effective and not so effective coping strategies or whether the ameliorative effects of such practices are inherently culture bound.

Acknowledgments

The research described in this article was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R29-MH57274 (to George A. Bonanno).

References

- Allport GW. Personality: A psychological interpretation. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist. 2004;59:20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Resilience in the face of potential trauma. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Colak DM, Keltner D, Shiota MN, Papa A, Noll JG, et al. Context matters: The benefits and costs of expressing positive emotion among survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Emotion. 2007;7:824–837. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Davis PJ, Singer JL, Schwartz GE. The repressor personality and avoidant information processing: A dichotic listening study. Journal of Research in Personality. 1991;25:386–401. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Field NP. Examining the delayed grief hypothesis across 5 years of bereavement. American Behavioral Scientist. 2001;44:798–816. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Field NP, Kovacevic A, Kaltman S. Self-enhancement as a buffer against extreme adversity: Civil war in Bosnia and traumatic loss in the United States. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:184–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Galea S, Bucciarelli A, Vlahov D. What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:671–682. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Keltner D. Facial expressions of emotion and the course of conjugal bereavement. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:126–137. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Keltner D, Holen A, Horowitz MJ. When avoiding unpleasant emotions might not be such a bad thing: Verbal–autonomic response dissociation and midlife conjugal bereavement. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1995;69:975–989. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Mancini AD. The human capacity to thrive in the face of potential trauma. Pediatrics. 2008;121:369–375. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Moskowitz JT, Papa A, Folkman S. Resilience to loss in bereaved spouses, bereaved parents, and bereaved gay men. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:827–843. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Noll JG, Putnam FW, O’Neill M, Trickett PK. Predicting the willingness to disclose childhood sexual abuse from measures of repressive coping and dissociative tendencies. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:302–318. doi: 10.1177/1077559503257066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Papa A, Lalande K, Nanping Z, Noll JG. Grief processing and deliberate grief avoidance: A prospective comparison of bereaved spouses and parents in the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:86–98. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Papa A, Lalande K, Westphal M, Coifman K. The importance of being flexible: The ability to both enhance and suppress emotional expression predicts long-term adjustment. Psychological Science. 2004;15:482–487. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Papa A, O’Neill K. Loss and human resilience. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 2001;10:193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Rennicke C, Dekel S. Self-enhancement among high-exposure survivors of the September 11th terrorist attack: Resilience or social maladjustment? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:984–998. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Singer JL. Repressor personality style: Theoretical and methodological implications for health and pathology. In: Singer JL, editor. Repression and dissociation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 435–470. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Lehman DR, Tweed RG, Haring M, Sonnega J, et al. Resilience to loss and chronic grief: A prospective study from preloss to 18-months postloss. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2002;83:1150–1164. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.5.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Nesse RM. Prospective patterns of resilience and maladjustment during widowhood. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:260–271. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Loss: Sadness and depression (Attachment and loss. Vol. 3. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR. Posttraumatic stress disorder: Malady or myth? New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW, al’Absi M, Lovallo WR. Cortisol fluctuates with increases and decreases in negative affect. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1999;24:227–241. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke CT, Shrout PE, Bolger N. Individual differences in adjustment to spousal loss: A nonlinear mixed model analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31:405–415. [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, House JS, Wortman C, Neese R, Kessler RC. Psychological adjustment to sudden and anticipated spousal loss among older widowed persons. Journals of Gerontology B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2001;56:S237–S248. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.4.s237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Shaver P, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coifman KG, Bonanno GA, Ray RD, Gross JJ. Does repressive coping promote resilience? Affective-autonomic response discrepancy during bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:745–758. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epel ES, McEwen BS, Ickovics JR. Embodying psychological thriving: Physical thriving in response to stress. Journal of Social Issues. 1998;54:301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Childhood and society. 2. New York: Norton; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley R, Bonanno GA. Attachment and loss: A test of three competing models on the association between attachment-related avoidance and adaptation to bereavement. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:878–890. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Davis KE, Shaver PR. Dismissing-avoidance and the defensive organization of emotion, cognition, and behavior. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford; 1998. pp. 249–279. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General Psychology. 2000;4:132–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology. 1998;2:300–319. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Losada MF. Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist. 2005;60:678–686. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Tugade MM, Waugh CE, Larkin GR. What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:365–376. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatzer-Levy I, Bonanno GA, Mancini AD. Reexamining identity continuity and complexity in adjustment to loss. 2008 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Goorin L, Bonanno GA. Would you buy a used car from a self-enhancer? Social benefits and illusions in trait self-enhancement. 2008 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2003;85:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1993;64:970–986. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.6.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Hiding feelings: The acute effects of inhibiting negative and positive emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:95–103. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Taylor SE. Social comparisons and adjustment among cardiac patients. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1993;23:1171–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Hock M, Krohne HW. Coping with threat and memory for ambiguous information: Testing the repressive discontinuity hypothesis. Emotion. 2004;4:65–86. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.4.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz MJ, Siegel B, Holen A, Bonanno GA, Milbrath C, Stinson CH. Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:904–910. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R. Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. New York: Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltman S, Bonanno GA. Trauma and bereavement: Examining the impact of sudden and violent deaths. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2003;17:131–147. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D. Facial expressions of emotion and personality. In: Magai C, McFadden SH, editors. Handbook of emotion, adult development, and aging. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D, Bonanno GA. A study of laughter and dissociation: Distinct correlates of laughter and smiling during bereavement. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1997;73:687–702. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Taylor C, Albright CA, Haskell WL. The relationship between repressive and defensive coping styles and blood pressure responses in healthy, middle-aged men and women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1990;34:461–471. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90070-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langens TA, Moerth S. Repressive coping and the use of passive and active coping strategies. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:461–473. [Google Scholar]

- Lalande KM, Bonanno GA. Culture and continuing bonds: A prospective comparison of bereavement in the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Death Studies. 2006;30:303–324. doi: 10.1080/07481180500544708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ, Ragan JD, Jones S. Talking facilitates cognitive-emotional processes of adaptation to an acute stressor. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2000;78:499–508. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ, Silver RC, Wortman CB, Wayment HA. Social constraints, intrusive thoughts, and depressive symptoms among bereaved mothers. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1996;70:271–282. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malatesta CZ. The role of emotions in the development and organization of personality. In: Thompson RA, editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Vol. 36. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1990. pp. 1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini AD, Bonanno GA. Resilience in the face of potential trauma: Clinical practices and illustrations. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session. 2006;62:971–985. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini AD, Bonanno GA. The role of worldviews in grief reactions: Longitudinal and prospective analyses. 2008a Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini AD, Bonanno GA. Stepping off the hedonic treadmill: A latent class analysis of spousal bereavement. 2008b Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini AD, Robinaugh D, Shear K, Bonanno GA. Does attachment avoidance help people cope with loss? The moderating effects of relationship quality. 2008 doi: 10.1002/jclp.20601. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Self-actualizing people: A study of psychological health. Personality: Symposium. 1950;1:11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton W, Moylan A, Raphael B, Burnett P, Martinek N. An international perspective on bereavement related concepts. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;27:457–463. doi: 10.3109/00048679309075803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, McBride A, Larson J. Rumination and psychological distress among bereaved partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:855–862. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.4.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff M, Langeland W, Gersons BPR. Effects of appraisal and coping on the neuroendocrine response to extreme stress. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29:457–467. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterweis M, Solomon F, Green F. Bereavement: Reactions, consequences, and care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:52–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Folkman S. Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology. 1997;1:115–144. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus DL. Interpersonal and intrapsychic adaptiveness of trait self-enhancement: A mixed blessing? Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1998;74:1197–1208. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J, Solomon S, Arndt J, Schimel J. Why do people need self-esteem? A theoretical and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:435–468. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Beer JS. Positive illusions about the self: Short-term benefits and long-term costs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:340–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin Z, Peplau LA. Who believes in a just world? Journal of Social Issues. 1975;31:65–89. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg SS, Janoff-Bulman R. Grief and the search for meaning: Exploring the assumptive worlds of bereaved college students. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 1991;10:270–288. [Google Scholar]

- Shuchter SR, Zisook S. The course of normal grief. In: Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Hansson RO, editors. Handbook of bereavement: Theory, research, and intervention. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1993. pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Armor DA. Positive illusions and coping with adversity. Journal of Personality. 1996;64:873–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Brown JD. Positive illusions and well-being revisited: Separating fact from fiction. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:21–27. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Lerner JS, Sherman DK, Sage RM, McDowell NK. Are self-enhancing cognitions associated with healthy or unhealthy biological profiles? Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2003;85:605–615. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Wood JV, Lichtman RR. It could be worse: Selective evaluation as a response to victimization. Journal of Social Issues. 1983;39:19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaka J, Blascovich J. Effects of justice beliefs on cognitive appraisal of and subjective physiological, and behavioral responses to potential stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:732–740. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaka J, Blascovich J, Kelsey RM. Effects of self-deception, social desirability, and repressive coping on psychophysiological reactivity to stress. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18:616–624. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaka J, Blascovich J, Kelsey RM, Leitten CL. Subjective, physiological, and behavioral effects of threat and challenge appraisal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:248–260. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaka J, Blascovich J, Kibler J, Ernst JM. Cognitive and physiological antecedents of threat and challenge appraisal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:63–72. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Davidson RJ. Frontal brain activation in repressors and nonrepressors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:339–349. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:320–333. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G. Adaptation to life. Boston: Little Brown; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger DA, Schwartz GE, Davidson RJ. Low-anxious, high-anxious, and repressive coping styles: Psychometric patterns and behavioral and physiological responses to stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1979;88:369–380. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.88.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisook S, Shuchter SR. Major depression associated with widowhood. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1993;1:316–326. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199300140-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]