Abstract

Crizotinib, a first-line anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has shown promising results for the treatment of locally advanced and metastatic lung cancer presenting the ALK rearrangement. On the other hand, secondary organizing pneumonia (OP) caused by anti-cancer drugs has been reported. While it is sometimes needed to rechallenge the suspected drug, the standard therapeutic strategy for secondary OP has not yet been established. We report a 60-year-old male with ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer who developed crizotinib-induced OP and was successfully rechallenged with crizotinib. Six months after the rechallenge, the patient has achieved a partial response. To our knowledge, this is the first case in which crizotinib-induced OP has been successfully treated.

Key Words: Lung cancer, Crizotinib, Organizing pneumonia, EML4-ALK

Introduction

Secondary organizing pneumonia (OP) caused by anti-cancer drugs has been reported. However, crizotinib-induced OP has not been described so far. Here, we report the case of a patient with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who developed crizotinib-induced OP and was successfully rechallenged with crizotinib.

Case Report

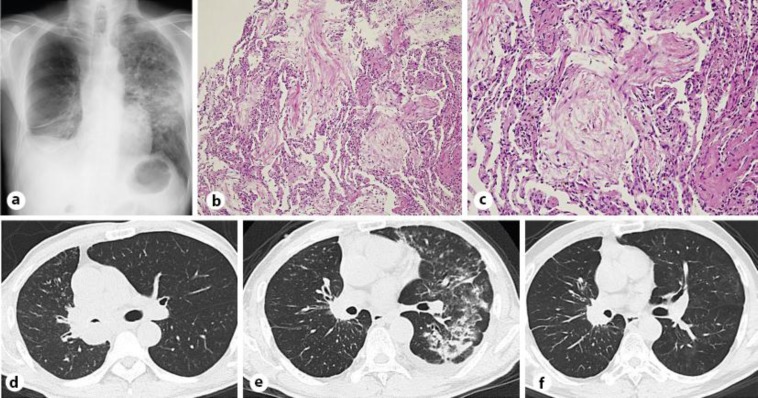

A 60-year-old male was diagnosed with lung adenocarcinoma (cT4N3M0, stage IIIB; fig. 1a, d). He was a current smoker with a smoking history of 30 pack-years and he had no allergies. Highly sensitive immunohistochemistry using 5A4 monoclonal antibody on a bronchoscopic biopsy specimen was positive for ALK protein [1]. A subsequent fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis using break-apart probes confirmed the ALK fusion gene. The patient was in a good general condition with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 1. As first-line therapy, crizotinib was administered orally at a dose of 250 mg twice daily. On day 50, while he had achieved a partial response by hisResponse Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors score, a chest computed tomography (CT) revealed a contralateral pulmonary infiltrate in the left lung (fig. 1e). Pulmonary function test showed a restricted dysfunction pattern. Transbronchial lung biopsy revealed lymphocytic alveolitis and OP (fig. 1b, c). No pathogens were found in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. The patient was diagnosed with secondary OP induced by crizotinib. Oral corticosteroid therapy was started at 30 mg/ 60 kg body weight (0.5 mg/kg) prednisolone, and the dose was reduced every 2 weeks. He responded well to the corticosteroid therapy and the infiltrate gradually improved. One and a half months after stopping crizotinib and 1 month after starting corticosteroid therapy, we readministered crizotinib at a dose of 250 mg 3 times a week, and the patient showed no signs of interstitial lung disease (ILD) recurrence. His restrictive pulmonary dysfunction improved. The dose of crizotinib was increased to 250 mg once daily, then to 400 mg once daily. He maintained a partial response after crizotinib rechallenge with a gradual improvement of ILD for 4 months and no ILD recurrence thereafter (fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

a Chest radiograph showed a unilateral infiltrate in the middle lung field of the left lung. b Transbronchial lung biopsy specimen from the left lower lobe showed intra-alveolar granulation tissue with myofibroblasts consistent with OP. HE. ×100. c Mass on body was seen on the transbronchial lung biopsy specimen. HE. ×200. d Chest CT scan showed a tumor lesion in the right pulmonary hilum and the narrowed right main bronchus. e Chest CT scan revealed panlobular lesions in the left lung. f Repeat chest CT scan showed a significant improvement of parenchymal changes 8 weeks after starting corticosteroid therapy without recurrence of OP.

Discussion

While a fatal case of crizotinib-induced ILD, for which the exact risk factors remain unclear, has recently been reported [2], there are some reports on a successful crizotinib retreatment after crizotinib-induced ILD [3, 4]. The risk factors of ALK-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)-induced ILD might to some extent be similar to those of epidermal growth factor receptor-TKI-induced ILD [4]. Although our patient was a male current smoker, and thus had two risk factors for epidermal growth factor receptor-TKI-induced ILD, there were no signs of ILD recurrence on crizotinib retreatment. The clinicopathological features of OP might be different from those of a fatal ILD. Ebina et al. [5] reported the disappearance of subpleural and interlobular lymphatics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) lungs along with a poor lymphogenesis and a significant decrease of alveolar lymphangiogenesis in comparison with cellular non-specific interstitial pneumonia and OP. These changes may exert a detrimental effect on IPF lungs by impairing alveolar clearance [5]. Another study showed that ILD with IPF/usual interstitial pneumonia patterns could be a risk factor for chemotherapy-induced ILD in advanced lung cancer patients [6]. Chemotherapy-induced ILD seems to occur more frequently in IPF/usual interstitial pneumonia patients than in non-IPF patients. Taken together, these facts may, at least in part, explain that the destruction of the alveolar modulatory effect in IPF lungs results in acute exacerbation of IPF and chemotherapy-induced ILD. However, the limited modulatory effect and clearance in the alveoli in OP lungs may have allowed the successful rechallenge with crizotinib, evading a severe inflammatory reaction in the lung [7].

Secondary OP may occur by any cause. Recent reports have demonstrated that molecular targeted inhibitors such as trastuzumab, tocilizumab, cetuximab and ipilimumab could cause OP. In all the reported cases of molecular inhibitor-induced OP to date, the drugs were stopped and never retried [8, 9, 10, 11]. While a standard treatment for drug-induced ILD and OP has yet not been established, molecular targeted inhibitors play an important role in cancer treatment. We have experienced the successful rechallenge with crizotinib in an ALK-positive NSCLC patient after crizotinib-induced OP. Therefore, it is important to consider if a rechallenge with the suspected drugs is possible, since it is often supposed to be difficult in the case of drug-induced ILD. An accurate diagnosis and a risk factor assessment for ILD seem to be important in treating ILD patients. For an accurate diagnosis of drug-induced ILD, transbronchial lung biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage should be considered for pertinent pathological evaluation.

In conclusion, this case highlighted the possibility of rechallenge crizotinib in ALK-positive NSCLC patients with crizotinib-induced OP. If crizotinib-induced ILD is suspected, bronchoscopic evaluation should be considered to determine the exact type of pulmonary pathology.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful for the diligent and thorough critical reading of our manuscript by Dr. Yoshihiro Ohkuni, chief physician, Taiyo, and John Wocher, executive vice president and director, International Aff1irs/International Patient Services, Kameda Medical Center (Japan).

References

- 1.Paik JH, Choe G, Kim H, et al. Screening of anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement by immunohistochemistry in non-small cell lung cancer: correlation with fluorescence in situ hybridization. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:466–472. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820b82e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamiya A, Okamoto I, Miyazaki M, Shimizu S, Kitaichi M, Nakagawa K. Severe acute interstitial lung disease after crizotinib therapy in a patient with EML4-ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e15–e17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanagisawa S, Inoue A, Koarai A, Ono M, Tamai T, Ichinose M. Successful crizotinib retreatment after crizotinib-induced interstitial lung disease. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:e73–e74. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318293dfc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asai N, Yamaguchi E, Kubo A. Successful crizotinib re-challenge after crizotinib-induced interstitial lung disease in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2014;15:e33–e35. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebina M, Shibata N, Ohta H, Hisata S, Tamada T, Ono M, et al. The disappearance of subpleural and interlobular lymphatics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lymphat Res Biol. 2010;8:199–207. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2010.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenmotsu H, Naito T, Kimura M, Ono A, Shukuya T, Nakamura Y, et al. The risk of cytotoxic chemotherapy-related exacerbation of interstitial lung disease with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1242–1246. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318216ee6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cordier JF. Organizing pneumonia. Thorax. 2000;55:318–328. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.4.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikegawa K, Hanaoka M, Ushiki A, Yamamoto H, Kubo K. A case of organizing pneumonia induced by tocilizumab. Intern Med. 2011;50:2191–2193. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barjaktarevic IZ, Qadir N, Suri A, Santamauro JT, Stover D. Organizing pneumonia as a side effect of ipilimumab treatment of melanoma. Chest. 2013;143:858–861. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radzikowska E, Szczepulska E, Chabowski M, Bestry I. Organizing pneumonia caused by transtuzumab (Herceptin) therapy for breast cancer. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:552–555. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00035502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chua W, Peters M, Loneragan R, Clarke S. Cetuximab-associated pulmonary toxicity. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2009;8:118–120. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2009.n.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]