Abstract

Objectives

To conduct a meta-analytic review of selective and indicated mentoring interventions for effects for youth at risk on delinquency and key associated outcomes (aggression, drug use, academic functioning). We also undertook the first systematic evaluation of intervention implementation features and organization and tested for effects of theorized key processes of mentor program effects.

Methods

Campbell Collaboration review inclusion criteria and procedures were used to search and evaluate the literature. Criteria included a sample defined as at-risk for delinquency due to individual behavior such as aggression or conduct problems or environmental characteristics such as residence in high-crime community. Studies were required to be random assignment or strong quasi-experimental design. Of 163 identified studies published 1970 - 2011, 46 met criteria for inclusion.

Results

Mean effects sizes were significant and positive for each outcome category (ranging form d =.11 for Academic Achievement to d = .29 for Aggression). Heterogeneity in effect sizes was noted for all four outcomes. Stronger effects resulted when mentor motivation was professional development but not by other implementation features. Significant improvements in effects were found when advocacy and emotional support mentoring processes were emphasized.

Conclusions

This popular approach has significant impact on delinquency and associated outcomes for youth at-risk for delinquency. While evidencing some features may relate to effects, the body of literature is remarkably lacking in details about specific program features and procedures. This persistent state of limited reporting seriously impedes understanding about how mentoring is beneficial and ability to maximize its utility.

Keywords: Delinquency, Mentoring, At-Risk Youth, Prevention

Youth mentoring has been of great interest to policy makers, community service providers, intervention researchers, and administrators interested in promoting it as a delinquency prevention approach (Grossman & Tierney, 1998). Mentoring is one of the most widely used approaches for such problems with over 5000 organizations in the United States offering some form of this approach (DuBois, Portillo, Rhodes, Silverthorn, & Valentine, 2011; MENTOR/National Mentoring Partnership, 2006). In fiscal year 2011 it is estimated approximately $100 million in federal support and research funds were dedicated to youth mentoring (DuBois et al., 2011). It was also one of the earliest interventions to show evidence in relation to affecting youth violence (Tolan & Guerra, 1994).

Definitions of mentoring vary, but common elements that can be identified (DuBois & Karcher, 2005, DuBois, et al., 2011; MENTOR/National Mentoring Partnership, 2009). Most commonly the central feature is a one-on-one relationship between a provider (mentor) and a recipient (mentee) for the potential of benefit for the mentee. For the purpose of this review, mentoring will be defined by the following 4 characteristics: 1) interaction between two individuals over an extended period of time, 2) inequality of experience, knowledge, or power between the mentor and mentee (recipient), with the mentor possessing the greater share, 3) the mentee is in a position to imitate and benefit from the knowledge, skill, ability, or experience of the mentor, 4) absence of the role inequality between provider and recipient that typifies most helping or intervention relationships where the adult is in authority over of directing expertise toward the child in need of teaching or specific help. This refers to relationships in which the adult is involved is based on professional training or certification of the provider or as occurs in parent-child, teacher-student, or other professional-client relationships. Thus, mentoring differs from professional-client relationships such as counseling or therapy, and from parenting or formal educational relationships. However, beyond these basic features and distinctions there has been limited determination of what are the processes through which mentoring is beneficial.

Broad meta-analyses and conceptual reviews suggest mentoring has much promise and compares favorably to other approaches to youth intervention (Aos, Lieb, Mayfield, Miller, & Pennucci, 2004, Hall, 2003, DuBois, Holloway, Valentine, & Cooper, 2002; DuBois et al., 2011; Rhodes, 2002, Rhodes, Bogat, Roffman, Edelmena, & Galasso, 2002; Lipsey & Wilson, 1998; Wilson, Gottfredson, & Najaka, 2001). Yet it was also one of the first interventions to also have produced evidence of negative effects in carefully controlled studies (e.g. McCord, 1978). However, none of the prior reviews focused specifically and exclusively on mentoring as an intervention to affect youth at-risk for delinquency. For example, Dubois et al. (2002) conducted a meta-analysis review that focused on mentoring without regard to inclusion criteria and across a broad set of outcomes. That review included examination of effects for “problem behavior” in comparison to several other outcomes such as educational attainment and vocational choice. Problem behavior was defined by measures of aggression, antisocial behavior, externalizing behaviors and delinquency, although there was no clear specification of indicators of delinquency within the general “problem behavior” outcomes. Instead studies were collapsed that considered any of these indicators. Similarly, DuBois et al. (2011) examined the same general categories and included studies with a broad range of populations. Notably that meta-analysis suggested effects might be greater for high-risk populations, although in that review high-risk is a category that includes a broad range of basis for inclusion. Lipsey and Wilson (1998) included mentoring interventions in their meta-analysis of serious juvenile offenders, however, they did not include precursors of serious offenses, such as aggression levels, substance use, or academic functioning which might be valuable mentoring outcomes for this population. In addition, in that review the focus was on serious offending only. As prevention efforts often are meant to affect these related outcomes concurrently and similar risk factors have been implicated across these outcomes, it seems important to determine if mentoring effects vary by these associated outcomes. Aos et al (2004) evaluated the cost effectiveness of various interventions for youth problems such as delinquency and teen pregnancy. Although their review suggested some mentoring programs show advantageous cost-benefit ratios, it restricted inclusion to studies that had information needed to calculate costs and render benefits. This meant only a few mentoring programs were considered. Thus, although these prior efforts provide valuable direction for this review and a strong basis against which to check our search results, they leave largely unanswered the question of how mentoring might affect youth at risk for delinquency, the magnitude of mentoring effects on delinquency, and how effects compare for other outcomes closely associated with delinquency and important in program design and development.

In addition to a gap in a meta-analytic focus on youth included due to risk for delinquency, the present review also focuses on features of the program implementation, training, providers, and processes to suggest what aspects of these are important contributors to effects. Nearly 20 years ago, in a review of empirical evidence supporting youth violence, it was noted that mentoring was among few approaches with multiple adequately-conducted trials showing significant effects but suffered as an area from limited attention to and description of intervention features that could help readers understand the intervention requirements (Tolan & Guerra, 1994). Unfortunately, little progress has been made in improving the state of intervention description and evaluation. There is still limited information about what features of mentoring are the bases for the observed positive effects (DuBois & Karcher, 2005). Reviews and evaluation studies have emphasized features such as differences in the mentor-youth engagement or youth skills at the start of mentoring such as social competency (DuBois et al., 2002. 2011; MENTOR/National Mentoring Partnership, 2009; Rhodes, 2005). An index of 11 recommended mentoring practices was used by DuBois et al. (2002) to attempt to suggest how practice differences might affect impact. As expected, there was a significant relation between this index score and effects. Notably, many of the index contributors were generic features that may well have been reflections of intervention results rather than design features (e.g. intervention length, quality of relationship, matching of mentor and recipient background and interests).

Effects of Important Features of Mentoring Programs

One aspect of mentoring intervention characteristics given substantial attention is the implication that a strong personal relationship between the mentor and mentee is a key to any benefits derived (DuBois et al., 2002; Rhodes et al., 2006). Thus one advance in the field is to assess how positive and engaging the relationship is between the mentor and mentee (Rhodes et al., 2006). For example, DuBois et al. (2011) report larger effect sizes when matching of mentor and youth was based on shared interests; presumably this improves likelihood of a good relationship. In most cases, a corollary is that the mentor is undertaking this activity, not as a professional in the helping or social service professions, but because of personal interest or sense of duty, often as a volunteer (Rhodes, 2002). When a person with professional background or duties to provide such services offers mentoring, the emphasis is more on the relationship and the personal interest in the mentee than on specific skills, activities, or formal protocols. Thus, it has been noted that one limitation of mentoring may be that providers may be less accountable as they are volunteers and/or may not be well prepared for challenges of developing and maintaining a relationship with sometimes challenging and less appreciative youth (Grossman & Tierney, 1998). In contrast, it may be that motivation that is not personal, that is for professional advancement or as a paid position might be expected to lessen the personal commitment and connection thought to spark effective mentoring. More understanding of how different reasons for undertaking mentoring influence effects would help with understanding effect variations and provide direction for improving impact. We test for differences by motivation of mentor for engaging in this work.

A second area of importance in understanding for directing mentoring efforts is how important structuring of the effort and expecting fidelity to an approach is for effects. While it is increasingly recognized that training in skills and expectations are important for mentoring, there is much less clarity about what is important to expect. Mentoring has been characterized as growing out of a mentor’s commitment to youth (Rhodes, 2002) with the accompanying implication that structuring the activities and processes to be ensured would detract from the individualistic authentic engagement that carries the benefits. In contrast, research on other forms of intervention have not supported such a view, pointing to more clear expectations and fidelity prescriptions as promoting larger effects (Tolan & Gorman-Smith, 2003). Thus, the extent to which there is emphasis on following these procedures and principles thought to be helpful should relate to effect levels. Therefore in this review we examine if assessment of fidelity relates to effect size.

A third question of importance about mentoring is the value of selectivity in inclusion for mentoring (Tolan & Brown, 1998). A corollary is the basis for inclusion, with many programs including all youth residing in a high risk community, usually defined as a lower socioeconomic area with elevated rates of crime (Tolan, 2000). There is some indication the effects might be greater for higher risk youth, although the results are not fully consistent (DuBois et al., 2011). There is not clarity if programs are more effective if youth are included or excluded due to elevated risk. There is evidence that preventive effect for high-risk youth may be quite different from that accrued for the general population (Tolan & Gorman-Smith, 2003). For example, it may be that mentoring is not valuable in affecting delinquency or related outcomes of high risk youth because it is not structured enough and focused on multiple risk factors thought to drive that behavior (Lipsey & Wilson, 1998).

Similarly, as others have noted it is common for mentoring to occur as part of a multi-component program, whether as one of several components or as a central focus augmented by additional supporting activities (Aos et al., 2004). This leaves open an important question of the extent to which effects attributed to mentoring might actually be coincidental inclusion with other effective components or if the effects might be greater with inclusion of additional program components, whether incidental to the mentoring or as full related but separate intervention services.

Identifying Potential Key Processes Defining and Differentiating Mentoring

In addition to these features of intervention organization, there is an important but almost unattended to issue of what processes are typical of and constitute the processes through which mentoring benefits occur. Are there activities or underlying purposes of activities that are defining of mentoring and that due to variation in emphasis across mentoring programs could account for differences in effects? Theoretical summaries of the field and attempts to relate mentoring to prevention science, developmental psychopathology, and/or youth development literature in general have suggested some likely key features of mentoring (Lipsey & Wilson, 1998; McCord, 1992; Tolan & Guerra, 1994). These processes are differentiated from the attention to the mentor-mentee relationship that has dominated discussion of mentoring organization (Rhodes, 2005, DuBois & Karcher, 2005). The latter represents an aspect of connection that while important as a basis for mentoring is a common basis for any influence relationship.

Through systematic review of theoretical organization of process models of mentoring (e.g., (MENTOR/National Mentoring Partnership, 2009; Rhodes, 2005), indices of best practice utilized by DuBois et al. 2002, components described in programs with significant effects (e.g., Davidson & Redner, 1988), and qualitative analyses of mentoring relationships (e.g. Deutsch & Spencer, 2009) we identified a set of processes that are often mentoring programs, whether explicitly described or implicit in the activities utilized. In addition, we compared mentoring to other helping interventions to identify distinguishing features. For example, mentoring is distinguished form psychotherapy by the non-professional relationship and the lack of emphasis on mental health problem alleviating. From these multiple bases we identified four processes as central to mentoring: 1) identification of the recipient with the mentor that helps with motivation, behavior, and bonding or investment in prosocial behavior and social responsibility; 2) provision of information or teaching that might aid the recipient in managing social, educational, legal, family, and peer challenges; 3) advocacy for the recipient in various systems and settings; and 4) emotional support and friendliness to promote self-efficacy, confidence, and sense of mattering (DuBois et al., 2002; DuBois et al., 2011; Rhodes et al., 2002). These processes are frequently mentioned individually as potential basis for mentoring benefits. For example, in a recent test, DuBois et al. (2011) report when advocacy was considered a mentor function effect sizes averaged .07 standard deviation units larger than when not.

Thus, the present report has three aims related to gaps in the literature at present. The first aim is to focus on a particular population of great interest and commonly mentioned when the value of mentoring is proclaimed. That population is youth at risk for delinquency and associated problems such as drug abuse, aggression, and school failure. Thus, different from other meta-analyses we limit inclusion to studies that selected youth because of risk for delinquency. The second aim is to examine the accumulated studies for this population for the relation to effects of key features of intervention organization and implementation such as basis for recipient inclusion, provider motivation and training, inclusion of other intervention components, and implementation and fidelity monitoring. The third emphasis is to apply organization of interventions around four key processes identified in prior reviews, specific program descriptions, and theoretical formulations that as a combination seem to define mentoring and differentiate it from other helping interventions. We test for differences in effects by emphasis on each of these four processes.

Organization of the Review

We focused on four interrelated outcomes in parallel; to examine how effects found for delinquency were consistent or different from a positive outcome (academic achievement) a related form of antisocial behavior (drug use) and an important precursor (aggression). Each of these outcomes are often targets of or measures of effects for programs for delinquents and each has been correlated with lower delinquency risk. These three associated outcomes also are important for planning prevention efforts, whether due to shared risk factors or shared effects from some prevention efforts (Tolan & Gorman-Smith, 2003). For example, aggression is often used as the predecessor and behavioral risk marker for later delinquency (Tolan & Gorman-Smith, 1998). Drug use, while a form of delinquency, has interest as a co-occurring problem with other criminal behavior and as an outcome of interest in its own right (Haegerich & Tolan, 2008). Similarly, school engagement and performance are seen as importxant outcomes for understanding preventive benefits for youth at-risk for delinquency.

Methods

Search Strategy for Identifying Relevant Studies

Three authors have conducted prior meta-analyses on mentoring or related topics prior to our review: 1) DuBois et al. (2002) on mentoring in general; 2) Lipsey and Wilson (1998) on delinquency interventions in general; and 3) Aos et al. (2004) on interventions for delinquency and associated social problems. Prior to conducting this review, each of these reviewers allowed us access to some of the materials used in their analyses. We found that one or more of these authors had already located many of the studies to be included in this analysis. However, we conducted our own review to locate studies done since these earlier reviews were completed and to locate other studies, including those that were unpublished at the time of these previous analyses. We used dates, sample sizes, authorship, and information provided on studies to determine whether two effects on the same outcome came from the same study. In the few instances where this occurred we used the outcome closest to post-test.

Search Terms and Databases

We based our search terms on those used by prior meta-analyses. We used a combination of terms in searching electronic databases and research registers. Table 1 shows the search terms used, although slight deviations in key words (including derivative forms of the listed terms) were required to achieve equivalent searches in some databases (e.g., choosing a broader search term when a narrower term was not supported in the database). Additional searches used combinations of the search terms in Table 1, each of which contained: 1) one of four outcomes (and derivative forms of these terms): delinquency, aggression, substance use, or academic achievement; 2) a cognate of mentoring; and 3) a cognate of intervention Databases were selected based on their potential relevance to the topic and to the outcomes of delinquency, academic achievement, aggression, and substance use more generally. The databases searched included PsychINFO, Criminal Justice Abstracts, Criminal Justice Periodicals Index, Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Science Citation Index (SCI), Applied Social Sciences Indexes and Abstracts (ASSIA), MEDLINE, Science Direct, Sociological Abstracts, Dissertation Abstracts, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, and ERIC (Education Resources Information Center). The following research registers were also searched: the Social, Psychological, Educational and Criminological Trials Register (SPECTR (for search prior to its ending), the National Research Register (NRR, research in progress), and SIGLE (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe). Finally, the reference lists of primary studies and reviews in studies identified from the search of electronic resources were scanned for any not yet identified that were relevant to the systematic review. All searches covered until July 2011.

Table 1.

Categories and Variables for Meta-Analysis

| Composite Category | Variables |

|---|---|

| Delinquency | Self-reports of delinquency |

| School conduct reports | |

| Teacher report form (TRF a) or teacher BASC b | |

| Delinquency scales | |

| Arrest records | |

| Court records | |

| Aggression | Peer nominations of aggression |

| Teacher reports on the TRF of BASC | |

| Parent CBCL c or BASC reports | |

| Self-reports | |

| Behavioral Observations | |

| Substance Use | Self-reports (e.g., SRD) |

| Arrest records | |

| Court records | |

| Teacher reports | |

| Parent reports | |

| Academic Achievement | School grades |

| Standardized test scores (e.g., ITBS d) | |

| Self-reports | |

| Archival graduation or withdrawal records |

TRF = Teacher Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991)

BASC = Behavioral Assessment System for Children (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992)

CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991)

ITBS = Iowa Test of Basic Skills (Hieronymous, Hoover & Lindquist, 1986)

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies in the review

The studies included in the meta-analysis satisfied all of the following inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were included in this review:

Outcomes measured

We focused this systematic review on outcomes related to juvenile delinquency. We included studies with outcome measures of juvenile delinquency, reported by the individual or by others, or derived from archival sources such as arrest or juvenile court records. We also included studies focusing on precursors of delinquency such as aggression or high levels of externalizing problems and studies with two outcomes that are correlated with and frequently co-occur with criminal involvement or delinquency risk (drug abuse and academic achievement/ school failure).

Selection of participants

We included studies that involved youth who were involved in the mentoring program being evaluated because they were “at-risk” for juvenile delinquency. This could include some prior delinquency and the juvenile justice system, if the goal of mentoring was to prevent further or future involvement. Environmental characteristics for which participants might be selected might include family and parenting influences on behavior, residence in neighborhoods with high levels of poverty or crime, and/or exposure to gangs (Tolan & Gorman-Smith, 2003). Individual characteristics for which participants might be selected include prior arrests for minor delinquency, high scores on screening measures for aggression, evidence of oppositional defiant or conduct disorders, school failure, or attitudes and beliefs consistent with elevated use of aggression or antisocial behavior (Farrington, 2004).

Intervention Type

We included interventions focusing on prevention and treatment (often referred to as selective and indicated population interventions). In the initial phase of study selection, we sought out any studies that described their interventions as mentoring, that mentioned mentoring as any part of their intervention strategy, or had interventions characterized by any of the four characteristics noted above, whether or not they specifically mentioned mentoring.

Regarding the defining characteristic of absence of formalized role inequality, previous reviews have differed on the inclusion of studies using professionals as mentors. DuBois et al. (2002) excluded interventions using professional providers, with the exception that some studies that employed mental health professionals as mentors were included under certain conditions (see DuBois et al., 2002; Rhodes, 2002 for those criteria). We differed from this prior review by including the few studies with mental health providers as mentors if their involvement was limited to mentoring as a general relationship based supportive activity and did not include psychotherapeutic engagement. Functionally this means inclusion here of some critical studies for the current focus that were not included in the DuBois review, such as the McCord Cambridge-Somerville study (McCord, 1978, 1979).

We excluded studies in which the intervention was explicitly psychotherapeutic, behavior modification, or cognitive behavioral training. Although we included studies in which mentoring was done as a part of another structured intervention, those studies that were conducted without providing results for the mentoring intervention separately were coded as including either an additional primary intervention (i.e., a major component in addition to mentoring) or an additional secondary intervention (i.e., a minor component in addition to mentoring).

In addition to requiring that studies investigate the effects of a mentoring intervention, as described above, we followed three additional criteria based on those used by Lipsey and Wilson (1998) in their meta-analysis of intervention effects on delinquency. We only included studies that measured at least one quantitative variable for one of the four outcomes considered here and that provided sufficient data to allow calculate an effect size and decipher its direction. When studies measured a delinquency-related outcome but did not report sufficient detail to allow calculation of an effect size, we attempted to contact the author to obtain additional information. Because of access to the Aos and Lipsey databases we had a relatively complete rendering of the studies from which such information could be extracted. There were, therefore, very few studies about which we were uncertain whether additional information was obtainable.

Research Design

Another criterion for inclusion in this review was that the study design involves a comparison that contrasted an intervention condition involving mentoring with a control condition. Control conditions could be “no treatment,” “waiting list,” “treatment as usual,” or “placebo treatment.” To ensure comparability across studies we made an a priori rule to not include comparisons to another experimental or actively applied intervention beyond treatment as usual. However, there were no such cases among the studies otherwise meeting criteria for inclusion.

We coded studies according to whether they were experimental or quasi-experimental designs. To qualify as experimental or quasi-experimental for the purposes of this review, we required each study to meet at least one of three criteria: 1) random assignment of subjects to treatment and control conditions or assignment by a procedure plausibly equivalent to randomization; 2) Individual subjects in the treatment and control conditions were prospectively matched on pretest variables and/or other relevant personal and demographic characteristics; 3) Use of a comparison group with demonstrated retrospective pretest equivalence on the outcome variables and demographic characteristics as described below

Randomized controlled trials that met the above conditions were clearly eligible for inclusion in the review. Single-group pretest-posttest designs (studies in which the effects of treatment are examined by comparing measures taken before treatment with measures taken after treatment on a single subject sample) were never eligible. A few nonequivalent comparison group designs (studies in which treatment and control groups were compared even though the research subjects were not randomly assigned to those groups) were included. Such studies were only included if they matched treatment and control groups prior to treatment on at least one recognized risk variable for delinquency, had pretest measures for outcomes on which the treatment and control groups were compared and had no evidence of group non-equivalence. We required that non-randomized quasi-experimental studies employed pre-treatment measures of delinquent, criminal, or antisocial behavior, or significant risk factors for such behavior, that were reported in a form that permitted assessment of the initial equivalence of the treatment and control groups on those variables.

Time Period and English Language Criteria

We limited the review to studies conducted within the United States or another predominately English-speaking country and reported in English. Juvenile subjects did not need to speak English. A study conducted in the United States or Canada with resident Hispanic youth, for example, could have been included.

We limited the review to studies published since 1970. The 41-year time frame between 1970 and the present (time of completion of search to conduct coding, 2011) is consistent with the work published during the time of substantial use of designs and measures with qualities we required for this review. IT also approximates the time period of the overall delinquency meta-analysis of Lipsey and Wilson (1998).

Coding of Article Characteristics

We organized this review by first examining the coding approaches utilized by Lipsey and Wilson (1998), Aos et al (2005), and DuBois et al. (2002 to make use of these reviews’ coding as much as possible. Because our interest included some characteristics not coded by any of these prior reviews and also our focus did not overlap exactly as to sample makeup and outcomes we did not simply replicate any of these coding schemes.

We double-coded 20% (N =32) of the articles, and calculated inter-coder reliability coefficients for study type (e.g., randomized trial), study quality, participant selection criteria (e.g., individual or behavioral risk), mentor motivations (e.g., personal motivation, civic duty, or professional development), and intervention components (e.g., modeling, teaching) using Cohen’s kappa. We found high reliabilities for study type (κ = 1.0), study quality (κ = .93), and selection criteria (κ = .81). Coders easily determined some mentor motivations (e.g., personal experience, (κ = .90), but were less certain about what was professional development (κ = .68). Final kappa reliabilities all were above .6, a level Landis and Koch (1977) suggested represented full agreement. Where disagreement or uncertainty arose we worked toward resolving technical differences and then consensus coding. A designated senior member of the study made final decisions (rarely needed).

We conducted a separate meta-analysis for each outcome (delinquency, aggression, drug use, academic achievement). Each grouping of studies was based on the outcome, such that some studies might be included in more than one meta-analysis due to measuring more than one outcome. Thirteen studies reported more than one outcome, four of which had three outcomes. A single outcome measure was used for each study for a given outcome category. No studies reported multiple measures of a single outcome (e.g., multiple measures of delinquency or aggression).

Statistical Procedures

Effect Size Calculations

For this study we used inverse-variance meta-analysis with a random-effects model, performed and plotted through the metagen package in the R statistical language. The random effects model addresses the research question of whether the average effects of an intervention in the population are significantly different from zero (Bailey, 1987; Raudenbush, 1994).

The inverse variance method, as its name suggests, weights individual studies by the inverse of the estimated variance of their effect sizes. Thus, this method requires the calculation of standard errors of the effect sizes. For this purpose, we estimated variances for each effect size according to Hedges and Olkin’s (1985, p. 86) Formula 14:

where σdi2 is the estimated variance of the effect size, ne is the number of experimental subjects, nc is the number of control subjects, and di2 is the square of the effect size of the study.

The standardized mean difference effect sizes of the interventions under evaluation were calculated in units of Hedges’ (1981) g. For studies reporting means, standard deviations, and Ns of numeric data, the effect size was calculated by dividing the treatment difference less the control difference over the pooled treatment and control standard deviation:

| where: M = mean | S = standard deviation |

| E = treatment | C = control |

| 1 = pretest | 2 = posttest |

For studies that reported dichotomous outcomes, we calculated odds ratios and converted them into an equivalent standardized mean difference effect size estimate (Lipsey & Wilson, 1998). Chinn (2000) noted that dividing the natural log of an odds ratio by π/√3 produces an excellent approximation of the standardized mean difference effect size.

We also applied a correction to all effect sizes that compensates for small sample bias:

We examined funnel plots from each meta-analysis for visual evidence of asymmetry, and conducted Egger tests (Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder 1997) to obtain a statistical test for asymmetry. The Egger test fits a regression of the normalized effect estimate (estimate divided by its standard error) against precision (the reciprocal of the standard error of the estimate).

We conducted analyses to determine whether the effects of the mentoring interventions varied by five key aspects of the intervention approach and characteristics. Potential moderators that were tested were:

selectivity in inclusion (high individual risk, high environmental risk, or no such selectivity)

whether or not mentoring is a stand-alone approach in that study or was undertaken along with a) some other major intervention components or b) some relatively minor add-ons

the motivation of the mentors in participating (civic duty, professional development, own experience)

the extent to which quality of work and fidelity were assessed or emphasized.

explicit attention to presence of four key processes: modeling/identification promotion, emotional support, advocacy, and teaching

Inspection of the coding across studies indicated we had to simplify some moderation analyses due to sparse or no studies noting a particular characteristic of interest. For selection of participants, none of the interventions were coded as a universal; thus, under selection we could only test for moderation by the presence or absence of selection for individual risk and selection for environmental or ecological risk. We could not consider personal experience as a motivation as there we no studies in which this was measured or was able to be coded. Thus moderation tests of mentor motivations were conducted separately for presence or absence of civic duty and for professional development as motivation.

Only the tests of inclusion of other interventions with mentoring included all 46 studies. Other moderator analyses were limited by whether coders could determine whether the moderating factor was present or absent. The analysis of whether motivation by civic duty significantly moderated effect sizes included 36 studies, which was the smallest number of studies in any of the moderation analyses.

To conduct the moderated analyses we utilized all studies across the four outcomes to calculate an overall effect size by moderator condition (i.e., the mean of all effect sizes reported in each study). This was done because of the limited number of studies for testing moderators available even if examined for each outcome separately. We also reasoned that the interest was in testing moderation of mentoring for studies of delinquency and related outcomes for this at-risk group rather than for each specific outcome. That is, this meta-analysis if focused on youth at-risk for delinquency and the view that the four outcomes are related in sharing risk factors and likely impact of mentoring features. This approach has been used in other meta-analyses where multiple outcomes are of interest (see DuBois et al., 2011). In addition, as in those approaches given the power strain moderation analyses can impose on data sets of interventions, we also utilized as has been done by others to not preclude indications of potentially important moderation a more liberal p level of .05 for a one-tailed test because in each case we expected larger effects if the moderator was present, and the specific order of the levels of the moderator was not at issue. This is equivalent to a two-tailed p < .10 which has been justified given the power challenges for moderation effects (Wilson & Lipsey, 2007).

We tested for moderation with meta-regression analysis using the rma function in the metafor package in R (Viechtbauer 2010). Each meta-regression analysis employed a random effects model that included terms for the moderator under consideration and a term representing whether the study was a randomized design or a quasi-experimental trial. The significance tests are one-tailed Z-tests.

We also conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the effects on conclusions of changes made to the inputs of an analysis (Morgan & Henrion, 1990). Accordingly, we conducted analyses to determine (1) the consistency of effect sizes obtained with different outcome variables, and (2) the consistency of outcomes within different levels of moderated analyses.

Results

Search and Selection Results

In the first phase of the literature search we identified 164 studies that were further evaluated for basic criteria for outcome and intervention type. Of these studies, 58 (34%) were determined to have none of the target outcomes. The remaining 107 were subjected to further scrutiny in order to determine their methodological suitability for the meta-analysis. Of these 53 (33%) had research designs that did not meet minimum quality standards for inclusion. and 6 (4%) did not provide sufficient information for calculating effect sizes related to the outcomes in question. These requirements yielded 46 (28%) studies that were included in the quantitative review. Detailed descriptions of the sample, intervention description, design features, and effects of each included study are available as part of the Campbell report (http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/lib/project/48/). Of the 46 studies included, 27 were randomized controlled trials and 19 were quasi-experimental studies involving non-random assignment, but with matched comparison groups as was described above. Twenty-five studies reported delinquency outcomes, 25 reported academic achievement outcomes, 6 reported drug use outcomes, and 7 reported aggression as an outcome.

Main Effect Meta-Analyses Results

Prior to calculating the mean effect size, we evaluated the heterogeneity of study effect sizes using multiple homogeneity measures, standard errors, and associated probability levels, including Cochrane’s Q, and I2 (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks & Altman, 2003). Cochrane’s Q is an indicator of heterogeneity that is distributed as a chi-square. Significant values of Q indicate heterogeneity. The degree of heterogeneity can be seen in the I2 statistics. This indicates the approximate proportions of variance across compared studies that are due to heterogeneity of effects.ii

We used forest plots of the effects and confidence intervals to explore potential outlying studies as reasons if heterogeneity of effects was detected. Our procedure was, after identifying possible outlying studies we repeated the meta-analyses, successively eliminating such studies in order to determine whether removal of up to five outlying studies would reduce or eliminate the heterogeneity. As can be seen in Table 2, heterogeneity of effects was substantial for delinquency and academic achievement. Also, examination of forest plots and re-analysis with removal of outliers successively did not reduce appreciably the heterogeneity of effects of mentoring for either delinquency or academic achievement. To assist in understanding the heterogeneity in effect sizes, we conducted an analysis to determine whether the effect sizes differed substantially between randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental designs. Using the Z-test recommended by Hedges and Pigott (2004, formulas 11-12, p. 432) for contrasting group mean effect sizes in meta-analysis, we tested the effect sizes obtained in quasi-experimental studies against those obtained in RCTs. The results are shown in Table 3. As can be seen there, although effect sizes were numerically larger in RCTs for all outcomes except drug use, none of the differences were statistically significant.

Table 2.

Standardized Mean Difference Effect Sizes and Homogeneity Statistics from Random Effects Mentoring Meta-Analyses

| Model | SMD | 95%CI | Z | τ2 | I2 | H | Q | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delinquency (k = 25 studies) | 0.21 | 0.17 – 0.25 | 9.84** | 0.01 | 99.3% | 11.72 | 3297.64** | 24 |

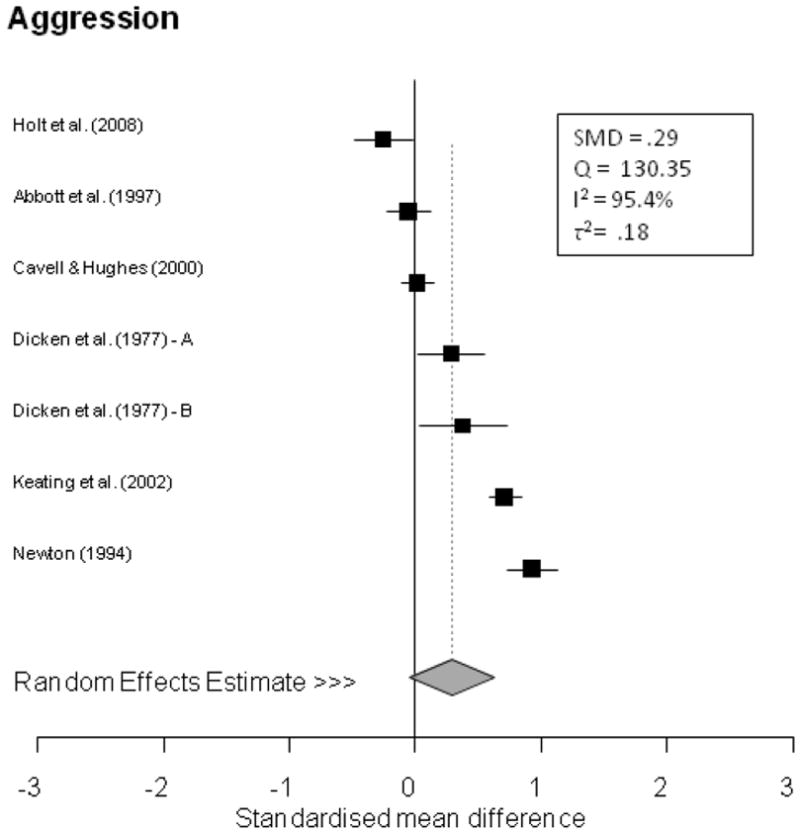

| Aggression (k = 7 studies) | 0.29 | -0.04 – 0.62 | 1.71 | 0.18 | 95.4% | 4.66 | 130.35** | 6 |

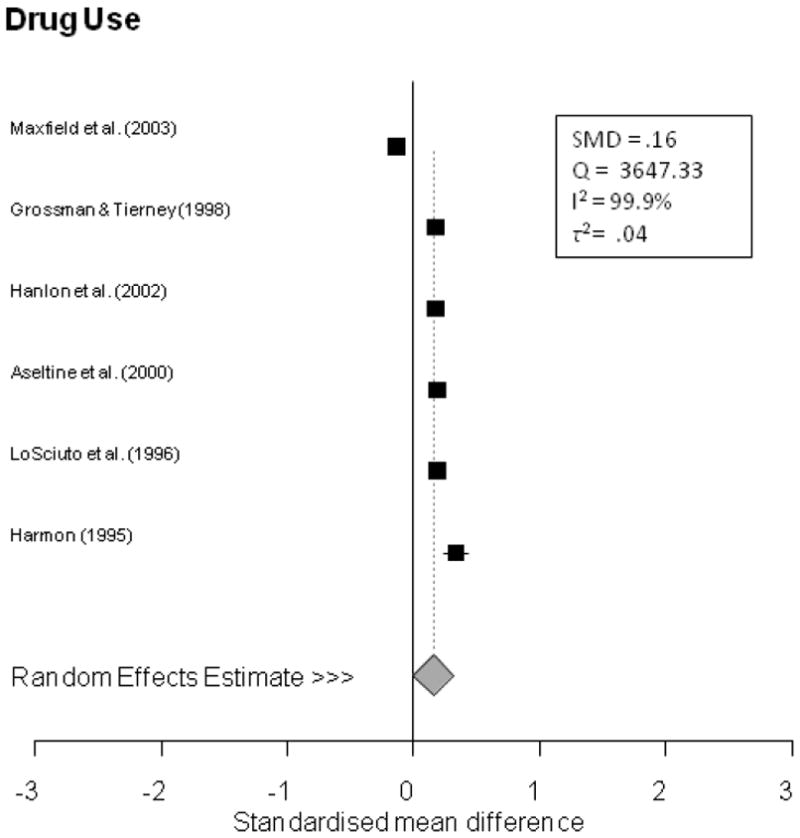

| Drug Use (k = 6 studies) | 0.16 | -0.00 – 0.32 | 1.93 | 0.04 | 99.9% | 27.01 | 3647.33** | 5 |

| Academic Achievement (k = 25 studies) | 0.11 | 0.07 – 0.15 | 5.86** | 0.01 | 60.0% | 1.58 | 59.95** | 24 |

| Overall Effects (k = 46 studies) | 0.18 | 0.15 - 0.21 | 10.80** | 0.01 | 99.2% | 11.50 | 5948.72** | 45 |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01

Table 3.

Differences in Mean Effect Sizes by Study Design

| Quasi-experimental Designs

|

Randomized Controlled Trials

|

Meta-Regression

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Studies | SMD | # Studies | SMD | B | SE | |

| Delinquency | 11 | 0.20 | 14 | 0.42 | .19 | .16 |

| Aggression | 3 | 0.14 | 4 | 0.41 | .26 | .29 |

| Drug Use | 3 | 0.19 | 3 | 0.13 | -.07 | .11 |

| Academic Achievement | 15 | 0.14 | 10 | 0.22 | .19 | .16 |

Based on the finding of heterogeneity across studies, a random effects model was calculated for each outcome. Table 3 lists for each outcome an average effect size and 95% confidence interval and a related Z statistic. To facilitate interpretation, we scaled all outcomes so that positive effect sizes represent effects in the desired direction, i.e., lower delinquency, aggression and drug use, higher academic achievement or lower school failure.

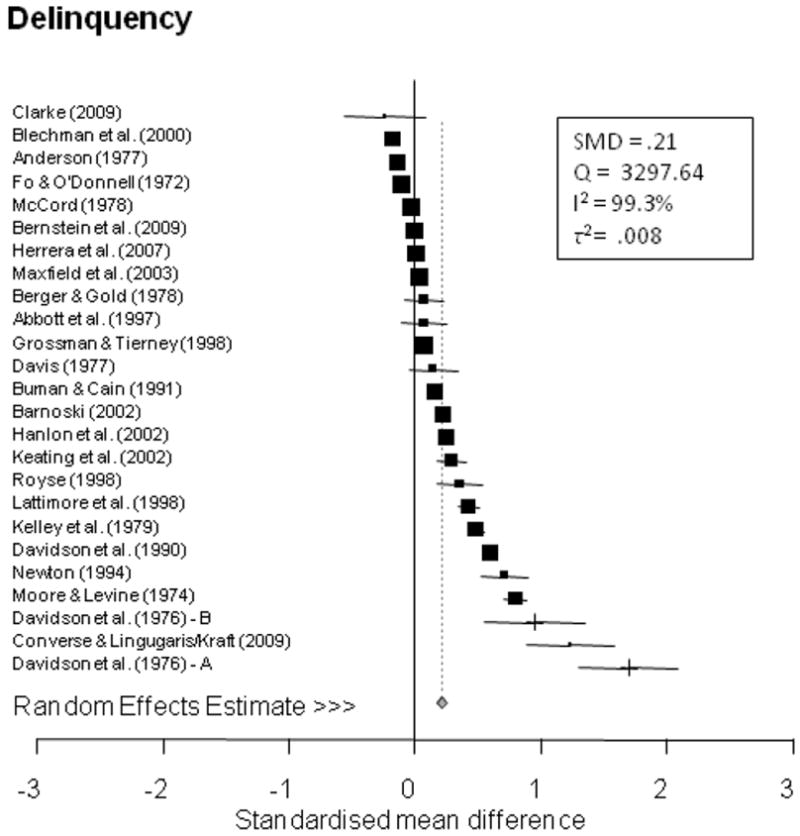

As can be seen in Table 3 the 25 studies on Delinquency yielded an average effect size of SMD =.21 (95% confidence interval .17 to .25; p < .01). Heterogeneity was substantial as indicated by I2 of 99.3% (Q (24) = 3297.64, p < .01). Examination of a funnel plot for delinquency revealed some asymmetry involving the three studies with the largest effect sizes, and an Egger test confirmed the presence of asymmetry (bias = 6.79, t (23)= 2.74, p < .05). We conducted a sensitivity analysis by removing these studies and repeating the meta-analysis. The difference was very slight. With the full sample, the SMD from the random effects model was 0.21 (p < .001; τ2 = .008). With the reduced sample the SMD from the random effects model was 0.19 (p < .001; τ2 = .008). Finally, we applied the trim and fill method (Duval & Tweedie 2000) to account for publication bias in the random effects estimate. The result was an estimated effect of 0.18 (p < .001; τ2 = .009).

As can be seen in Table 3 a random effects model of the seven studies with Aggression outcome yielded an average weighted effect size of SMD = .29 (95% confidence interval: -0.03 to 0.62, ns). The funnel plot for Aggression revealed no asymmetry and the Egger test confirmed this impression (bias = -1.41, t (5) < 1, ns).

Similarly, a random effects model of the six studies with Drug Use outcome yielded an average weighted effect size of SMD = .16 (95% confidence interval: 0.04 to 0.29, p = .05; see Table 3). There appeared to be funnel plot asymmetry for Drug Use due to the single negative effect, but the Egger test did not find evidence of bias (bias = 16.41, t (4) < 1, ns). Removal of this effect in a sensitivity analysis resulted in stronger combined effect (Full sample: SMD = .16, p = .05, τ2 = .04; Reduced sample: SMD =.19, p < .001, τ2 = .0002).

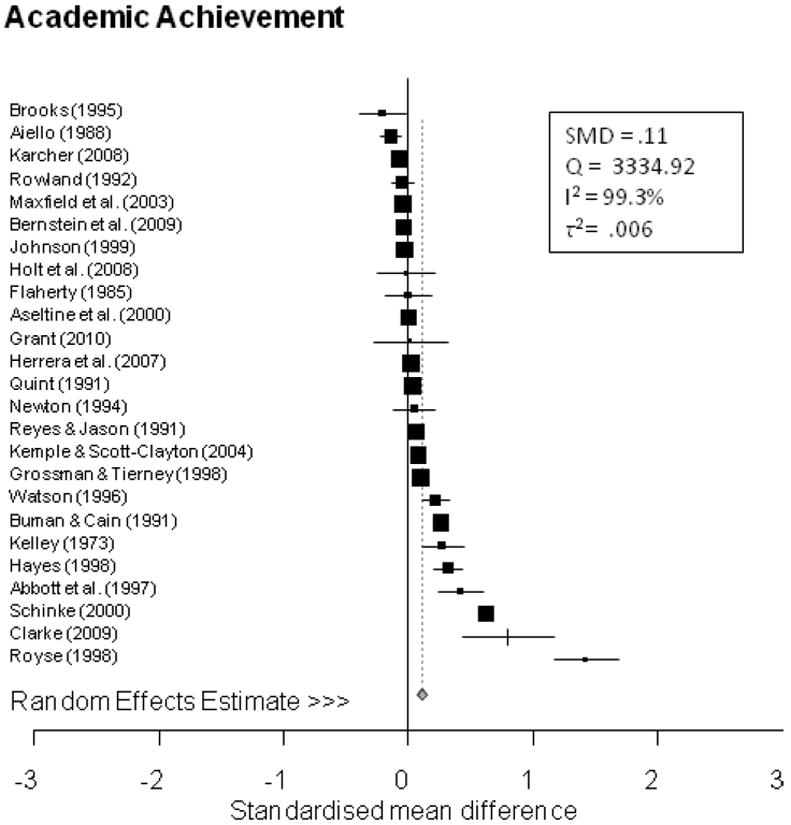

The random effects model of 25 studies with Academic Achievement outcome yielded an average effect size of SMD = .11 (95% confidence interval: 0.03 to 0.31; see Table 3). On academic achievement, graphical examination suggested that there might be funnel plot asymmetry due to three studies with large effect sizes. Removal of these effects in a sensitivity analysis resulted in a weaker, but still significant combined effect (Full sample: SMD=.11, p < .0001, τ2 = .006; Reduced sample: SMD =.05, p < .01, τ2 = .005). An Egger test of bias found no evidence of bias with the full sample (bias=4.55, t (23) = 1.65, p = .11).

We also created forest plots for each outcome to show the variation in individual studies about the aggregate effect size. These are the effect sizes from inverse variance weighted random effects models. These are provided, with accompanying statistics, in Figures 1-4, corresponding to Delinquency, Aggression, Drug Use, and Academic Achievement respectively. Across the four outcomes the pattern is one of relatively consistent direction and effect sizes within a given outcome, but with a few studies showing confidence intervals that include zero or negative effects for each outcome. The patterns of effect sizes and the Forest Plots suggest the average effect sizes represent robust estimates of mentoring on each outcome. The aggregate effect size estimates, although modest, are all positive.

Figure 1.

reports studies measuring outcomes related to delinquent involvement.

Forest plots of meta-analysis of the effects of mentoring interventions for each outcome. The size of the center square shows the weight assigned to the study and the width of the error bars shows the 95% confidence interval for the effect size of each study.

Figure 4.

reports effects on illegal drug use.

Forest plots of meta-analysis of the effects of mentoring interventions for each outcome. The size of the center square shows the weight assigned to the study and the width of the error bars shows the 95% confidence interval for the effect size of each study.

Moderator Analyses

To check the validity of combining across outcomes we tested for bias in effects due to this aggregation (e.g. effects are limited to one outcome or heavily dependent on specific outcome). To do so we conducted two sets of sensitivity analyses. For the first set of analyses, we employed Hedges and Pigott’s (2004, formulas 11-12, p. 432) method for contrasting group mean effect sizes in meta-analysis to contrast effect sizes from studies reporting delinquency outcomes against those reporting each outcome against those reporting on the other three outcomes. These results produced no evidence that effect sizes differed substantially by any given outcome, which would mean moderation relations were not due to a true relation with only a single outcome, Z (delinquency-aggression) = -0.17, ns; Z (delinquency-drug use) = 1.61, ns; Z (delinquency-academic) = 1.77, ns; Z (aggression-drug use) = 0.74, ns; Z (aggression-academic) = 0.81, ns; and Z (academic-drug use) = -0.07, ns. We also coded outcomes of each study according to the outcome variables used (e.g., 1-4 = Delinquency, Aggression, Drug Use, Academic Achievement). We then cross-tabulated these codes with categorical scores for whether a given moderator could be coded. No significant results were obtained. Only one moderator, professional development as a motivation for mentoring, showed any such tendency, with a marginally higher than expected frequency by outcome (for academic achievement) χ2 (5, n=36) = 11.05, p < .05 (one-tailed test). These results suggested to us sufficient confidence that moderation analyses collapsed across outcomes would be not biased or misrepresenting an overall relation for mentoring programs. In combination with the practical consideration of sample size limitations we judged this an appropriate way to serve the goals of the review with the available studies.

We tested for moderation using two methods. First, we calculated meta-analysis statistics separately by levels of the moderators (Hunter & Schmidt, 2004, p. 402). Table 4 reports the standardized mean difference effect sizes by levels of each moderator, the number of studies in each level of the moderator, and the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals for each random effect estimate (one tailed tests). Table 4 also reports the moderator effect estimates, standard errors, and significance tests from the meta-regression analyses described above.

Table 4.

Moderation of Mentoring Effects (Random Effects Models)

| Moderator | Level of Moderator | Meta-Regression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Absent | Present | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| k | SMD | L | U | k | SMD | L | U | B | SE | |

| Mentee Selection | ||||||||||

| Individual Risk | 22 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 16 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Environmental Risk | 28 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 8 | 0.23 | -0.06 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Other Interventions | 23 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.34 | 23 | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.49 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Motivations of Mentors | ||||||||||

| Civic Duty | 11 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.47 | 21 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.35 | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| Professional Development | 20 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 16 | 0.42 | 0.16 | 0.68 | 0.21* | 0.11 |

| Quality and Fidelity Checks | ||||||||||

| Quality Check | 14 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.35 | 20 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.38 | -0.00 | 0.10 |

| Fidelity Check | 27 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 6 | 0.29 | -0.15 | 0.73 | 0.05 | 0.14 |

| Key Processes | ||||||||||

| Modeling/Identification | 28 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.40 | 11 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.56 | 0.06 | 0.12 |

| Emotional Support | 12 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 27 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.50 | 0.22* | 0.12 |

| Teaching | 11 | 0.12 | -0.01 | 0.24 | 30 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.44 | 0.15 | 0.10 |

| Advocacy | 32 | 0.13 | -0.05 | 0.31 | 10 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.72 | 0.17* | 0.09 |

Notes:

p <.05, one-tailed

Random effects models of standardized mean differences (SMD) are the sources of the significance tests for the SMDs within levels of each moderator. The meta-regression models are mixed effects models using full maximum likelihood estimation.

k = number of studies, SMD = standardized mean difference, L = lower limit of the 95% confidence interval for the SMD, U = upper limit of the 95% confidence interval for the SMD

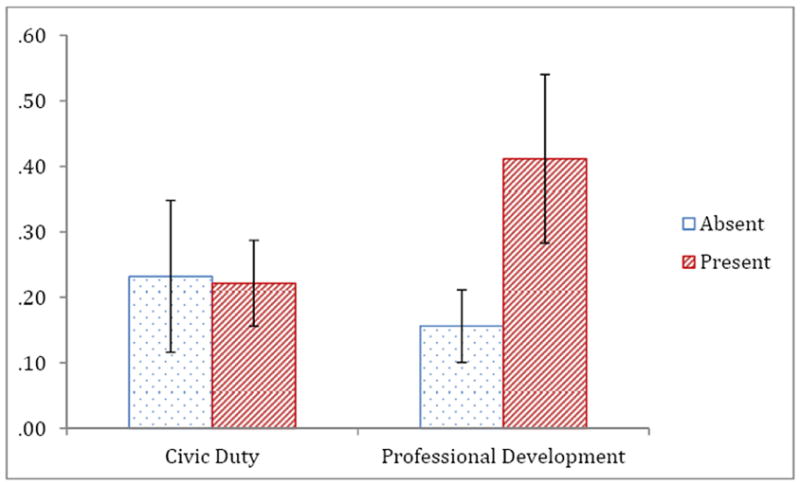

Moderator analyses of selectivity in recipient inclusion, inclusion of other components with mentoring, motivation of mentors, and attention to implementation and/or fidelity yielded significant moderation for Motivation for Mentoring but not for other program organization and implementation features (see Table 4). A plot of comparisons for Motivation for Mentoring suggest that when mentors were motivated by professional development there were larger effects (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

graphs moderation of overall effects by two possible motivations of mentors, civic duty and professional development.

Plots of average overall standardized mean difference (SMD) effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals by levels of moderating variables.

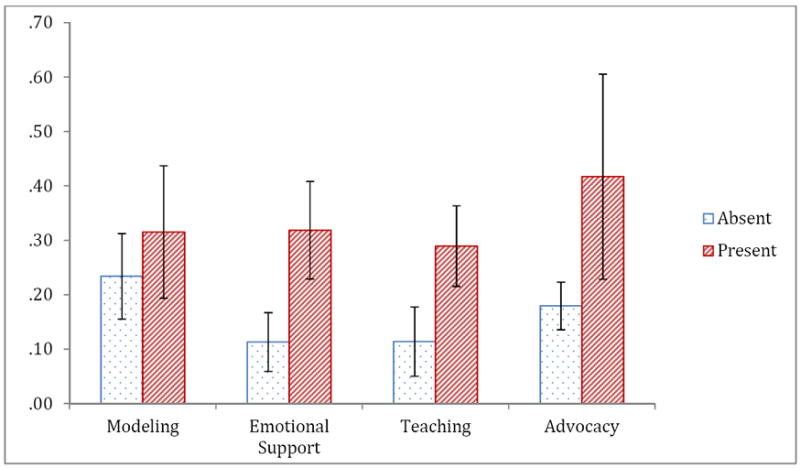

In regard to the four suggested key processes of mentoring interventions, there was evidence of significant moderation by the presence of two component processes in mentoring: Advocacy and Emotional Support (See Table 4). The results are illustrated in Figure 6. Stronger effects were observed when Emotional Support and Advocacy were components of mentoring than when these components were not present. Figure 6 also suggests that stronger effects were observed when teaching was a component of mentoring, but the meta- regression that included a term for research design did not return significant evidence of moderation.

Figure 6.

graphs the overall effect estimates by the presence or absence of key processes in the mentoring intervention, including emotional support, promotion of modeling or identification with the mentor, and teaching.

Plots of average overall standardized mean difference (SMD) effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals by levels of moderating variables.

Discussion

This review of the methodologically adequate studies released between 1970 and 2011 and focused on primarily United States population testing mentoring for high-risk youth found positive effects for delinquency and for three other associated outcomes: aggression, drug use, and academic performance. The effects are significantly different from zero for all four outcomes. However, all were modest in size (ranging from .11 for Academic Achievement to .16 for drug use, .21 for delinquency and .29 for aggression). These effect sizes are comparable to other interventions aimed at high-risk youth for each outcome. These results suggest mentoring, at least as represented by the included studies, has positive effects for these important public health problems with those at risk for delinquency. As this portion of the population can be of particular interest given the problems their elevated risk for not just delinquency but many other areas of functioning, the evidence of mentoring having significant effects, even if modest in size, suggest it could be part of the strategies to try to prevent actual engagement in delinquency and drug use and to curtail or prevent aggression and poor academic achievement (Tolan & Gorman-Smith, 2003). In addition, there was substantial heterogeneity in effect size across programs for each outcome suggesting there may be more substantial benefits that could be gained from mentoring is organized in ways that maximize those features associated with larger effects.

However, there were several limitations of the available literature that preclude statements about what makes mentoring most effective or what accounts for benefits. Perhaps most notably, the collected set of articles is remarkably limited in how limited the descriptions of the actual program activities, what were expected and not among a range of potential mentoring activities, and how key implementation features were organized, trained, and/or assessed for competence and fidelity. Unfortunately this state of reporting detail and completeness does not seem to be improving such that more recent publications are clearly more informative. The notable lack of adequate reporting of specific components, implementation procedures and adherence, and measurement of targeted processes to permit comparison on these important features is seen as a major impediment to advancing knowledge about the value of this popular approach to youth intervention. It may be that full potential of the approach is not being achieved, as what may improve effects is difficult to discern. Thus, we have limited ability to explain the implications of the lack of significance in some moderation analyses or to accord too much confidence to those that were significant.

In regard to intervention organization and implementation features, the results suggest that effects were larger when mentors were motivated to participate by interest in advancing their professional careers. The comparison was to coding for a specific motivation of mentor or not. Thus, the finding is one of this versus no specific motivation. This qualification considered, this is an important finding as most mentoring is undertaken as voluntary activity. Also, it does not seem entirely consistent with the assumption that the best mentoring is volunteers motivated intrinsically to help youth. In some cases the mentoring may help a mentor by fulfilling requirements at work, as an entry level position toward a professional staff position, or by enabling experience that can make them a more attractive candidate for educational or occupation opportunities. While beyond the scope of this review, the results may also raise questions about the presumption that mentoring should not be done other than as a voluntary activity.

Although the review focused on selective and indicated populations (those with risk characteristics or already exhibiting delinquency as a basis for inclusion) we did not find moderation by whether inclusion depended on individual risk characteristics or environmental or other-than-individual characteristics. While duly cautious about interpreting these null effects, the finding may suggest that either approach may be viable for effective targeting youth at risk for delinquency for mentoring.

We also did not find effect differences by whether or not other interventions were included with mentoring or mentoring was part of a multi-component intervention than when it was offered on its own. This leaves open whether or not the effects when other interventions are present is attributable to mentoring. The lack of effect does suggest that mentoring, at least as represented in these collected studies, has effects apart from those attributable to other interventions. However, it may be that this lack of difference is due to quality of specificity in descriptions of mentoring programs such that when a program is mentoring only or when other interventions occur incidentally or planfully along with it is not always determinable with certainty. Knowing more about whether adding other components add to, have not effect, or diminish mentoring benefits can provide basic direction for program planners and also may be critical in cost effectiveness analyses. Such information may also be important in considering characteristics such as the relative popularity of mentoring, relative ease of training and sustaining mentoring systems, and other factors that might make mentoring favored as a stand alone or as part of a multi-component intervention.

Similarly, we did not find differences by whether or not implementation extent and fidelity of implementation of expected activities and program features was undertaken. While what comprises a mentoring program to test fidelity against is in some cases not clear, the impression from the limited number of studies we could code for this is that this field is behind others in such design and evaluation considerations. As with the others noted here, more attention to this would likely improve understanding and improve efficiency of program improvement.

Moderation tests of four key processes found to be mentioned frequently in the literature and in description of some programs found that at least two matter in regard to effects. Programs that included emphasis on emotional support and those that emphasized advocacy for the recipient had larger effects. While teaching and modeling/identification did not significantly relate to effect size, there was some suggestion these may be worthwhile foci of attention in mentoring design. Perhaps with more studies that could be coded and more attention to documentation of such processes, the role of these four processes can be better delineated. One contribution of this meta-analysis is to undertake some defining of what constitutes and differentiates mentoring from other approaches. This seem fundamental to identifying what is common to mentoring programs and what makes them distinctly useful. The present results suggest programs might want to ensure emotional support from the mentor is emphasized but also methods and opportunities to advocate could also be helpful. Our results in regard to the latter are consistent with those reported by DuBois et al. (2011) for mentoring in general when measured across many outcomes.

These findings are consistent with prior meta-analyses that overlap in focusing on mentoring. As reported by Lipsey and Wilson (1998) and DuBois et al. (2002, 2011) these analyses suggest general support for mentoring for intervention related to delinquency and closely associated outcomes. However, as with those analyses, sparse information had to be relied on to try to delve into what might explain these effects. The lack of specificity constrains comparisons, undercuts confidence about what it is that constitutes the processes and implementation features that make mentoring effective. Given the prominence of mentoring in attempts to address these critical public health and youth problems, such a lack of systematic attempts to unpack mentoring and to understand it within a conventional framework for evaluating interventions is surprising. It is also striking that funding and promotion of these efforts proceeds without more stringent evaluation, including more careful identification of population of interest, inclusion criteria, skills and training of providers, content and theorized processes of component effects, fidelity tests, and implementation levels for intent to treat.

Figure 2.

reports effects related to academic achievement.

Forest plots of meta-analysis of the effects of mentoring interventions for each outcome. The size of the center square shows the weight assigned to the study and the width of the error bars shows the 95% confidence interval for the effect size of each study.

Figure 3.

reports effects on aggression or externalizing behaviors.

Forest plots of meta-analysis of the effects of mentoring interventions for each outcome. The size of the center square shows the weight assigned to the study and the width of the error bars shows the 95% confidence interval for the effect size of each study.

Footnotes

This report is based on a Campbell Collaboration systematic review. A more extensive report including the coding protocol and summary information on the included and excluded studies can be found there (http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/lib/project/48/). This includes tables summarizing components and findings of all included studies.

In a sensitivity analysis we tested for influence of studies with multiple outcomes on effects and found that the effect sizes in studies with single outcomes (SMD = 0.27, 95% CI = 0.12 - 0.41) were slightly but not significantly higher than the effect sizes in studies with multiple outcomes (SMD = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.07 - 0.38). Cross-tabulation of multiple outcomes by moderator variables revealed a single significant difference. Studies with a single outcome were more likely to have selected for environmental or ecological risk than were studies that reported multiple outcomes, χ2 (1, N=36) = 3.94, p < .05

Contributor Information

Patrick H. Tolan, University of Virginia

David B. Henry, University of Illinois, Chicago

Michael S. Schoeny, University of Chicago

Peter Lovegrove, University of Virginia.

Emily Nichols, University of Virginia.

References

- Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:663–694. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aos S, Lieb R, Mayfield J, Miller M, Pennucci A. Benefits and costs of prevention and early intervention programs for youth. Olympia: Washington State Institute for Public Policy; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey KR. Inter-study differences: How should they influence the interpretation and analysis of results? Statistics in Medicine. 1987;6:351–358. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier SR, Rosenfeld WD, Spitalny KC, Zansky SM, Bontempo AN. The potential role of an adult mentor in influencing high-risk behaviors in adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2000;154:327–331. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 2000;19:3127–3131. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3127::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WS, Redner R. The prevention of juvenile delinquency: Diversion from the juvenile justice system. In: Price RH, Cowen EL, Lorion RP, Ramos-McKay J, editors. Fourteen ounces of prevention: Theory, research, and prevention. New York: Pergamon; 1988. pp. 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- DesJarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N The TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:362. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch N, Spencer R. Capturing the magic: Assessing the quality of youth mentoring relationships. New Directions in Youth Development: Theory, Practice and Research. 2009;121:47–70. doi: 10.1002/yd.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Holloway BE, Valentine JC, Cooper HM. Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:157–197. doi: 10.1023/A:1014628810714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois dL, Karcher JJ. Youth mentoring: Theory, research, and practice. In: DuBois DL, Karcher MJ, editors. Handbook of youth mentoring. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Rhodes JE. Youth mentoring: Bridging science with practice. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:547–565. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Portillo N, Rhodes JE, Silverthorn N, Valentine JC. How effective are mentoring programs for youth? A systematic assessment of the evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2011;12(2):57–91. doi: 10.1177/1529100611414806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, Wells AM. Primary prevention mental health programs for children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:115–152. doi: 10.1023/a:1024654026646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eby LT, Rhodes J, Allen TD. Definition and evolution of mentoring. In: Allen TD, Eby LT, editors. Blackwell handbook of mentoring: A multiple perspectives approach. Oxford: Blackwell; 2007. pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP. Developmental and life-course criminology: Key theoretical and empirical issues. Criminology. 2003;41:221–255. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman JB, Tierney JP. Does mentoring work? An impact study of the Big Brothers Big Sisters program. Evaluation Review. 1998;22:403–426. [Google Scholar]

- Haegerich T, Tolan PH. In: Core competencies and prevention of adolescent substance use. Guerra NG, Bradshaw C, editors. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Larson R, Jensen LA, editors. New Directions in Child Development. New York: Josey-Bass; Youth at risk: Core competencies to prevent problem behaviors and promote positive youth development; pp. 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hall JC. Mentoring and young people: A literature review. Glasgow, Scotland: The SCRE Centre, University of Glasgow; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. New York: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, Pigott TD. The power of statistical tests for moderators in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:426–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JE, Schmidt FL. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings. 2. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jekielek SM, Moore KA, Hair EC, Scarupa HJ. Mentoring: A promising strategy for youth development. Washington, DC: Child Trends; 2002. research brief. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Effective intervention for serious juvenile offenders: A synthesis of research. In: Loeber R, Farrington D, editors. Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 313–341. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. A thirty-year follow-up of treatment effects. American Psychologist. 1978;33(3):284–289. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.33.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. Following up on Cambridge-Somerville: Response to Paul Wortman. American Psychologist. 1979;34(8):727. [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. The Cambridge–Somerville study: A pioneering longitudinal experimental study of delinquency prevention. In: McCord J, Tremblay RJ, editors. Preventing antisocial behavior: Interventions from birth through adolescence. New York: Guilford; 1992. pp. 196–206. [Google Scholar]

- MENTOR/National Mentoring Partnership. Mentoring in America 2005: A snapshot of the current state of mentoring. Alexandria, VA: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MENTOR/National Mentoring Partnership. Elements of effective practice for mentoring. 3. Alexandria, VA: Author; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED512172.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan G, Henrion M. Uncertainty: A guide to dealing with uncertainty in quantitative risk and policy analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- National Mentoring Working Group. Mentoring: Elements of effective practice. Washington, DC: National Mentoring Partnership; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell CR, Lydgate T, Fo WS. The buddy system: Review and follow-up. Child Behavior Therapy. 1979;1:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW. Random effects models. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, editors. The handbook of research synthesis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE. Stand by me: The risks and rewards of mentoring today’s youth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE. A theoretical model of youth mentoring. In: DuBois DL, Karcher MA, editors. Handbook of youth mentoring. Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage Press; 2005. pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE, Bogat GA, Roffman J, Edelman P, Galasso L. Youth mentoring in perspective: Introduction to special issue. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:149–155. doi: 10.1023/A:1014676726644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes J, Reddy R, Roffman J, Grossman J. Promoting successful youth mentoring relationships: A preliminary screening questionnaire. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26:147–168. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-1849-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE, Spencer R, Keller TE, Liang B, Noam G. A model for the influence of mentoring relationships on youth development. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34(6):691–707. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts H, Liabo K, Lucas P, DuBois D, Sheldon TA. Mentoring to reduce antisocial behavior in childhood. British Medical Journal. 2004;328:512–514. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7438.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH. Crime prevention: Focus on youth. In: Wilson JQ, Petersilia J, editors. Crime. Oakland, CA: Institute for Contemporary Studies Press; 2002. pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. What violence prevention can tell us about developmental psychopathology. Developmental and Psychopathology. 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Guerra NG. What works in reducing adolescent violence: An empirical review of the field. Boulder: University of Colorado, Center for the Study and Prevention of Youth Violence; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Henry D, Schoeny M, Bass A, Lovegrove P, Nichols E. Mentoring interventions to affect juvenile delinquency and associated problems: Update of previous review. 2013 http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/lib/project/48/

- Wilson DB, Gottfredson DC, Najaka SS. School-based prevention of problem behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2001;17(3):247–272. [Google Scholar]

References for Studies Included in Systematic Review

- Abbott DA, Meredith WH, Self-Kelly R, Davis ME. The influence of a Big Brothers program on the adjustment of boys in single-parent families. Journal of Psychology. 1997;131:143–156. doi: 10.1080/00223989709601959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello HS. Assessment of a mentor program on self-concept and achievement variables of middle school underachievers. (Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 1988) Dissertation Abstracts International. 1988;49(07):1699A. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson PS. Volunteers in criminal justice: A three-year evaluation of the Clark County, Washington program. Vancouver, WA: Health and Welfare Planning Council; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Aseltine RH, Dupre M, Lamlein P. Mentoring as a drug prevention strategy: An evaluation of Across Ages. Adolescent and Family Health. 2000;1(1):11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Barnoski R. Preliminary findings for the Juvenile Rehabilitation Administration’s Mentoring Program. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy; 2002. WSIPP Doc # 02-07-1202. [Google Scholar]

- Berger RJ, Gold M. An evaluation of a juvenile court volunteer program. Journal of Community Psychology. 1978;6:328–333. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein L, Rappaport C, Olsho L, Hunt D, Levin M. Impact evaluation of the US Department of Education’s student mentoring program. National Center for educational evaulation and regional assistance; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blechman EA, Maurice A, Buecker B, Helberg C. Can mentoring or skill training reduce recidivism? Observational study with propensity analysis. Prevention Science. 2000;1(3):139–155. doi: 10.1023/a:1010073222476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks LJ. An evaluation of the VCU Mentoring Program (Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University, 1995) Dissertation Abstracts International. 1995;57(04):1481A. [Google Scholar]

- Buman B, Cain R. The impact of short term, work oriented mentoring on the employability of low-income youth. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Employment and Training Program; 1991. Available from Minneapolis Employment and Training Program 510 Public Service Center, 250 S 4th St., Minneapolis, MN 55415. [Google Scholar]

- Cavell TA, Hughes JN. Secondary prevention as context for assessing change processes in aggressive children. School Psychology. 2000;38(3):199–235. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke L. PhD Dissertation. The State University of New Jersey; United States--New Jersey: 2009. Effects of a school-based adult mentoring intervention on low income, urban high school freshman judged to be at risk for drop out: a replication and extension. [Google Scholar]

- Converse N, Lignugaris/Kraft B. Evaluation of a school-based mentoring program for at-risk middle school youth. Remedial and special education. 2009;30 [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WS., II The diversion of juvenile delinquents: An examination of the processes and relative efficacy of childhood advocacy and behavioral contracting. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1976) Dissertation Abstracts International. 1976;37(01):601. University Microfilms No. AAT 7616113. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WS, II, Redner R. Prevention of juvenile delinquency: Diversion from the juvenile justice system. In: Price RH, Cowen EL, Lorion RP, Ramos-McKay J, editors. Fourteen Ounces of Prevention: A Casebook for Practitioners. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 1988. pp. 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WS, II, Amdur RL, Mitchell CM, Redner R. Alternative Treatments for Troubled Youth: The Case of Diversion from the Justice System. New York: Plenum Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WS, Seidman E, Rappaport J, Berck PL, Rapp NA, Rhodes W, Herring J. Diversion program for juvenile offenders. Social Work Research and Abstracts. 1977;13(2):40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WS, Redner R. The prevention of juvenile delinquency: Diversion from the juvenile justice system. In: Price RH, Cowen EL, Lorion RP, Ramos-McKay J, editors. Fourteen ounces of prevention: Theory, research, and prevention. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association; 1988. pp. 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Davis H. A mentor program to assist in increasing academic achievement and attendance of at-risk ninth grade students (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 1988) Dissertation Abstracts International. 1988;50(03):0580A. [Google Scholar]

- Dicken C, Bryson R, Kass N. Companionship therapy: A replication of experimental community psychology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1977;45(4):637–646. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.45.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty BP. An experiment in mentoring for high school students assigned to basic courses. (Doctoral dissertation, Boston University, 1985) Dissertation Abstracts International. 1985;46(02):0352A. [Google Scholar]

- Fo WSO, O’Donnell CR. The Buddy System model: Community-based delinquency prevention utilizing indigenous nonprofessionals as behavior change agents. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education & Welfare Office of Education; 1972. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No 074-394. [Google Scholar]