Abstract

The family Actinomycetaceae comprises several important pathogens that impose serious threat to human health and cause substantial infections of economically important animals. However, the phylogeny and evolutionary dynamic of this family are poorly characterized. Here, we provide detailed description of the genome characteristics of Trueperella pyogenes, a prevalent opportunistic bacterium that belongs to the family Actinomycetaceae, and the results of comparative genomics analyses suggested that T. pyogenes was a more versatile pathogen than Arcanobacterium haemolyticum in adapting various environments. We then performed phylogenetic analyses at the genomic level and showed that, on the whole, the established members of the family Actinomycetaceae were clearly separated with high bootstrap values but confused with the dominant genus Actinomyces, because the species of genus Actinomyces were divided into three main groups with different G+C content. Although T. pyogenes and A. haemolyticum were found to share the same branch as previously determined, our results of single nucleotide polymorphism tree and genome clustering as well as predicted intercellular metabolic analyses provide evidence that they are phylogenetic neighbors. Finally, we found that the gene gain/loss events occurring in each species may play an important role during the evolution of Actinomycetaceae from free-living to a specific lifestyle.

Keywords: Actinomycetaceae, Trueperella pyogenes, comparative genomics, phylogeny, gene gain/loss

Introduction

The family Actinomycetaceae was originally identified in 1918 (Buchanan 1918) and was the only member of the order Actinomycetales following the update of 16S rRNA signature nucleotide patterns (Zhi et al. 2009). The membership of this family had been changed for several times along with the improvement of taxonomic techniques, such as phenotypic characteristics, chemotaxonomic, numerical phenetic, and molecular genetic procedures (Slack 1974; Schaal et al. 2006). As currently defined, the family Actinomycetaceae comprises six valid genera including Actinomyces, Actinobaculum, Varibaculum, Mobiluncus, Arcanobacterium, and Trueperella (Collins, Jones, Kroppenstedt, et al. 1982; Spiegel and Roberts 1984; Lawson et al. 1997; Stackebrandt et al. 1997; Hall et al. 2003; Schaal et al. 2006; Yassin et al. 2011). Most of the members have been exclusively found as commensals or pathogens of humans and warm-blooded animals.

Although there were increasing studies concerning the accession and classification of new species in Actinomycetaceae during the past century, the current taxonomy might not satisfy the interests of related researchers due to the limited knowledge of genomic information. The established phylogenetic patterns of Actinomycetaceae were primarily dependent on the sequence analyses of 16S rRNA; however, single-gene-based phylogenetic analyses may provide limited phylogenetic information and reliable additional differential characteristics are hardly available (Schaal et al. 2006; Funke et al 2010; Yassin et al. 2011). For example, the species of the genus Actinomyces can form different phylogenetic clusters depending on the cutoff branching points, as the bootstrap values of branching are fairly low (Schaal et al. 2006). Additionally, the generic name of Trueperella pyogenes has been changed at least four times (Cummins and Harris 1956; Barksdale et al. 1957; Collins and Jones 1982; Collins, Jones, Schofield, et al. 1982; Ramos et al. 1997; Yassin et al. 2011). Here, we provided the genome sequence of T. pyogenes, in combined with that of related lineages, to provide the genomic level insight into the classification and genome divergence during the evolution of the family Actinomycetaceae.

Genome Sequencing and Analyses of T. pyogenes TP8

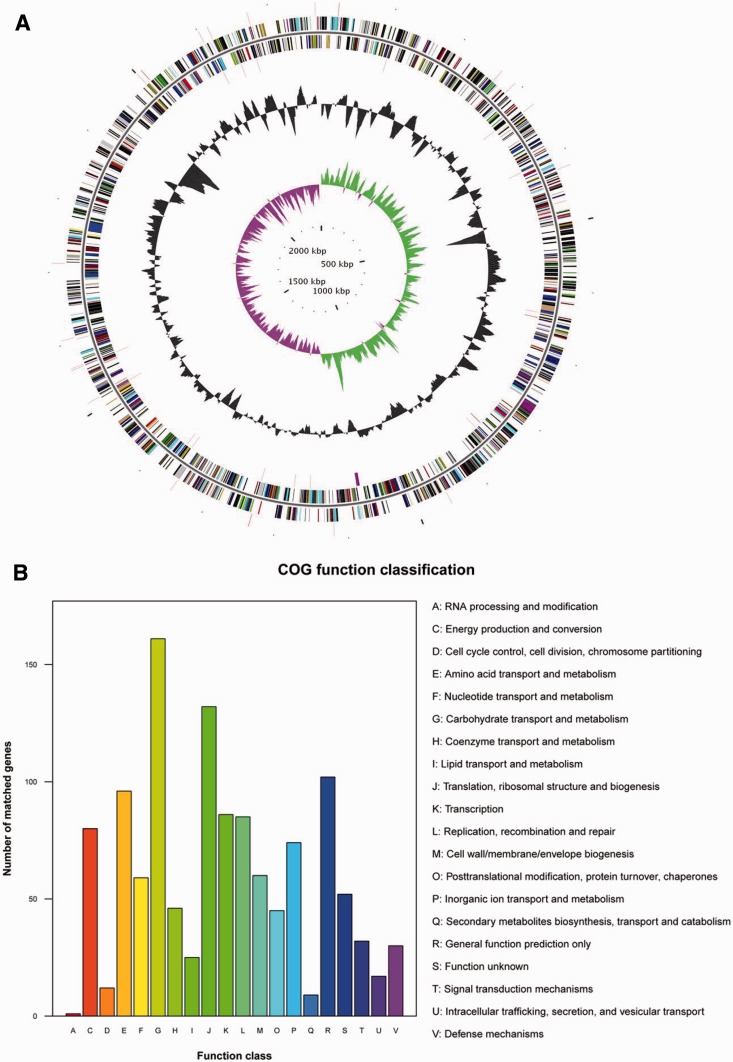

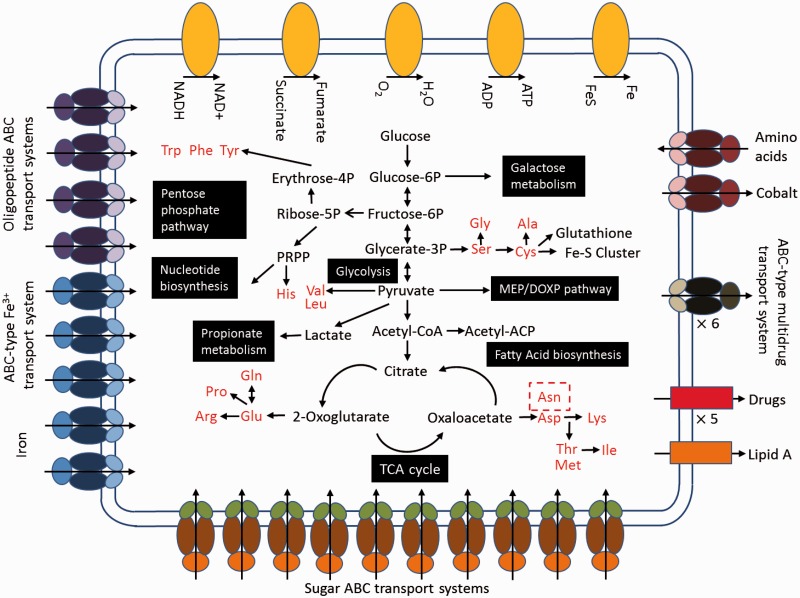

The T. pyogenes TP8 strain was isolated from the abscess of forest musk deer (Zhao et al. 2011) and was subjected to whole-genome sequencing. The genome was sequenced to greater than 15× coverage using the 454 sequencing platform, and then the high-quality sequence data were assembled into 14 contigs by Newbler2.6. A total size of 2.27-Mb genome sequence was subsequently acquired after the gaps were complemented by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification (fig. 1A and supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). The coding DNA sequences contain 2,105 open reading frames (ORFs) with a total length of 2,045,904 bp covering about 90.03% of the whole genome after genome annotation. A Type 1 CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)/Cas (CRISPR-associated) system containing a long CRISPR array (30 repeats) was identified (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). A total of 1,105 genes were affiliated with known Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs), of which 947 represented specific functional categories (excluding 106 “general function prediction only” and 52 “function unknown”) (fig. 1B). The integrated intracellular metabolic pathway of T. pyogenes TP8 was predicted based on the database of kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) (fig. 2 and supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). Critically, our result here was also confirmed by parallel analyses using the two recent reports of T. pyogenes genome sequences (Goldstone et al. 2014; Machado and Bicalho 2014). Additionally, T. pyogenes has one carbon pool by folate, which can be synthesized through nucleotide biosynthesis (supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online).

Fig. 1.—

General features of T. pyogenes TP8. (A) Graphical circular map of the genome showing (from outside to centre): Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes, GC content, GC skew. (B) COGs function classification of T. pyogenes TP8.

Fig. 2.—

An overview prediction of the T. pyogenes TP8 metabolism and transport. The main elements of metabolic pathways in the T. pyogenes TP8 genome are shown in black. Amino acids are in red.

Comparative Genomic Analyses between Arcanobacterium haemolyticum and T. pyogenes

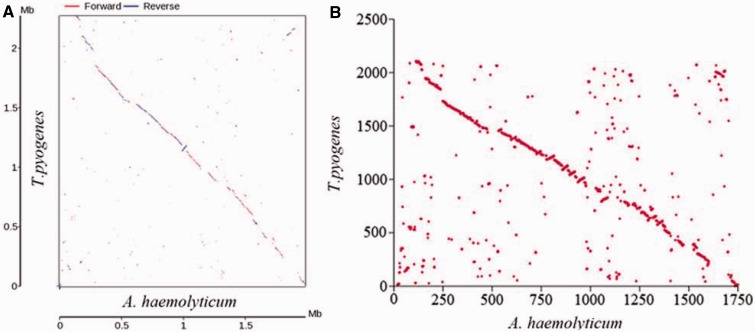

The classification between Arcanobacterium haemolyticum and T. pyogenes had been discussed for several decades. Previous studies used to suggest not only that both organisms were related to the streptococci, but also that A. haemolyticum should be a mutant form of T. pyogenes (Cummins and Harris 1956; Barksdale et al. 1957). In this study, our comparative genomics analysis between A. haemolyticum (Yasawong et al. 2010) and T. pyogenes showed that they have large areas of synteny in nucleotide sequence and relative ORF positions of orthologs (fig. 3). However, functional difference analyses suggested that T. pyogenes contains more ORFs (>300) than A. haemolyticum, covering almost all aspects of bacterial performance as confirmed by the gene ontology term analysis (supplementary fig. S4, Supplementary Material online). The result of KEGG pathway analysis showed that T. pyogenes has more advantages in metabolisms especially some amino acids and in causing human diseases (supplementary fig. S5, Supplementary Material online). Finally, the comparison of predicted global metabolic pathways of A. haemolyticum and T. pyogenes suggested that T. pyogenes has a more comprehensive intracellular metabolism system than that of A. haemolyticum such as lipid and amino acid metabolism (supplementary fig. S6, Supplementary Material online). These differences may be the genetic basis for why T. pyogenes can invade extensive host types and provide a plausible evidence for the distinction of A. haemolyticum and T. pyogenes.

Fig. 3.—

Comparative genomic analyses of T. pyogenes TP8 and A. haemolyticum DSM 20595. (A) Synteny analyses of T. pyogenes TP8 and A. haemolyticum DSM 20595 based on the nucleotide sequence. (B) Relative ORF positions of orthologs in T. pyogenes TP8 versus A. haemolyticum DSM 20595.

Phylogenomic Analyses of Actinomycetaceae

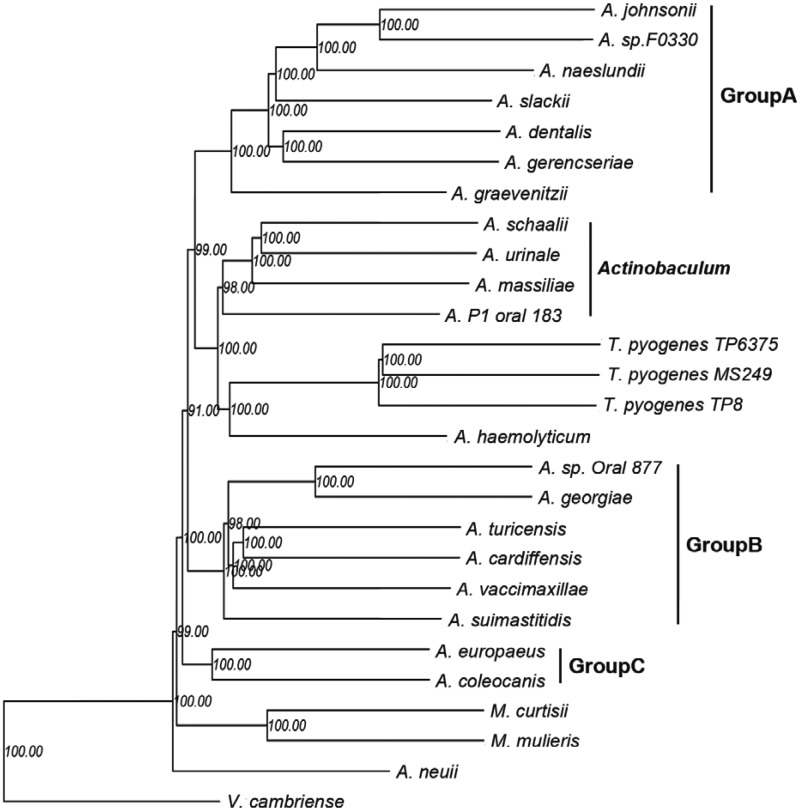

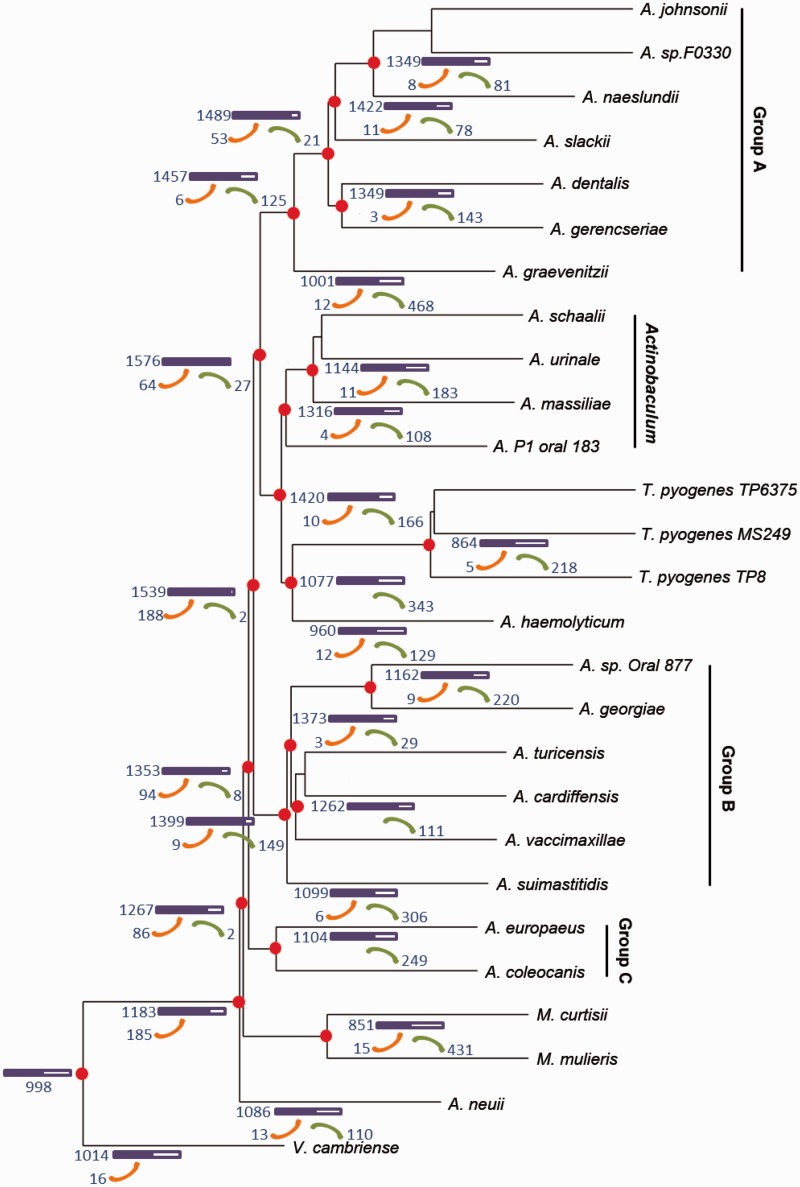

The participation of T. pyogenes genomic sequence allows us to systematically analyze the evolution of Actinomycetaceae at the genomic level. After alignment of whole COGs, a total of 186 common genes with single copy in all taxa were obtained (supplementary data sheet S1, Supplementary Material online). The phylogenetic tree was then constructed using maximum-likelihood (ML) estimation based on the nucleotide sequences of the 186 ancestral genes (fig. 4). On the whole, the genera Varibaculum, Actinobaculum, and Mobiluncus could be readily distinguished from their closest phylogenetic relatives but may be indistinguishable from the dominant genus Actinomyces. Notably, the species of genus Actinomyces were divided into three main groups with high bootstrap values and different G+C content (supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). Therefore, our results here were convincing compared with the previous discussion on the classification of Actinomyces based on 16S rRNA analysis (Schaal et al. 2006). However, as previously determined, A. haemolyticum and T. pyogenes also shared the same branch (Schaal et al. 2006; Funke et al. 2010; Yassin et al. 2011). We then utilized a total of 267,240 identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to construct another phylogenetic tree and showed similar lineage classification with the COG tree (supplementary fig. S7, Supplementary Material online). Surprisingly, A. haemolyticum was apart from T. pyogenes although the bootstrap value was relatively low. We then searched for more information by performing whole COGs-based genome clustering (supplementary fig. S8 and data sheet S2, Supplementary Material online), the similarity coefficient of COG patterns between T. pyogenes and A. haemolyticum was lower than that between T. pyogenes and A. coleocanis and A. europaeus. Overall, our current results in conjunction with the previous analysis 16S rRNA and chemotaxonomic characteristics as determined by Yassin et al. (2011), indicated that T. pyogenes and A. haemolyticum should be classified into two different but highly phylogenetic related lineages.

Fig. 4.—

Common gene contents tree of the main species in the family Actinomycetaceae. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on single-copy genes that simultaneously present in all species using ML estimation with a bootstrap value of 1,000 replications. All the 188 trees were merged by MP-EST in the website http://bioinformatics.publichealth.uga.edu/SpeciesTreeAnalysis/mpest/mpest.php (last accessed September 27, 2014) (Liu et al. 2010). The inferred numbers of genes presented in the main node (red dots) and each species are shown. Orange crooked arrow: gene gains. Green crooked arrow: gene losses.

Functional Enrichment and Gene Gain/Loss Analyses

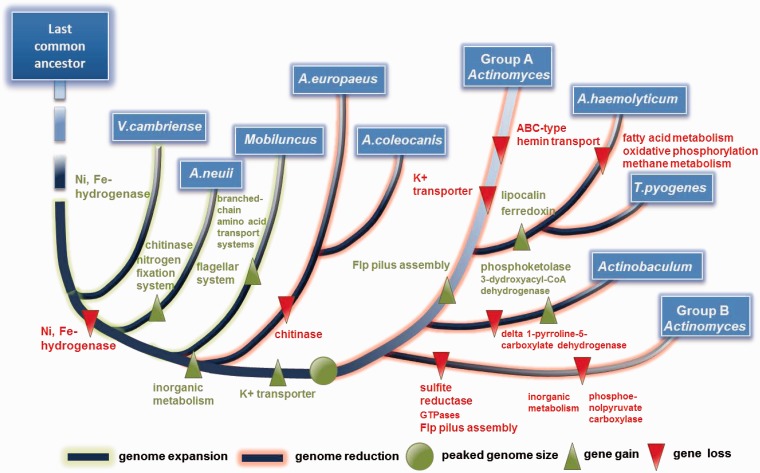

To gain insight into the evolutionary dynamics of the family Actinomycetaceae, we then investigated the gene gain/loss events that might have happened during the evolution of the family Actinomycetaceae (fig. 5). On the basis of which, the evolutionary history of Actinomycetaceae was delineated by comparing the enriched COG terms of extant gene content as well as gained and lost genes of each taxon (fig. 6). The family Actinomycetaceae initially experienced a significant genome expansion because a series of gene gain events happened in the early stage of speciation. After comparison of the gene content between taxa, all the species share 998 genes that were probably vertically transferred from the last common ancestor. All groups possess the phosphotransferase systems, which might be necessary for the species to colonize a wide range of hosts and the initiation of abscess (Deutscher et al. 2006; Richards et al. 2014). Interestingly, a large amount of gene loss events happened during lateral evolution which might be due to the adaption in specific environments. For instance, the species of genus Actinobaculum have a unique K+ transporter and ABC-type hemin transport system (supplementary data sheet S3, Supplementary Material online), which may contribute to the colonization of Actinobaculum in urine or blood of hosts.

Fig. 5.—

Gene gain and loss events in the evolution of the family Actinomycetaceae. The tree from figure 3 was used as a guide for the reconstruction. Purple frame, gene content; Orange arrow, gene gain; Green arrow, gene loss.

Fig. 6.—

History of Actinomycetaceae evolution.

In conclusion, the current study provided detailed genome landscape of T. pyogenes and the critical phylogenetic analyses among the species of the family Actinomycetaceae in genomic level. The relationship between T. pyogenes and A. haemolyticum as well as the classification of Actinomyces were further discussed. Moreover, our gene gain/loss analysis revealed a dynamic genome evolution pattern of Actinomycetaceae: Lateral gene losses might be the primary mechanism that facilitates the formation of new lineage and specialization in habitat colonization.

Materials and Methods

Genome Sequencing and Annotation of T. pyogenes TP8

The T. pyogenes strain T. pyogenes TP8 was isolated from the abscess of body surface of forest musk deer (Miyaluo Farm, Sichuan Province, China), which is an economically important ruminant and categorized as the first class key species protected by the Chinese legislature since 2002 (Guha et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2011). Genome DNA was isolated with QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAgen) and sequenced on the 454 sequencing platform at the Beijing Genomics Institute and resulted in greater than 15-fold sequencing coverage. High-quality data were assembled by Newbler2.6 and the gaps were then complemented by PCR amplification. Automatic gene prediction and annotation were performed using Glimmer3.02 (Delcher et al. 2007) and BLAST programs (Altschul et al. 1997). The circular genome visualization was performed by CGView (Stothard and Wishart 2005). The obtained entire ORFs were then assigned to the database of COGs (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG) and KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/, last accessed June 1, 2014) following the instructions of website, respectively.

Comparative Genomics Analyses between A. haemolyticum and T. pyogenes

The genome sequence of A. haemolyticum DSM 20595 was reannotated as the process of T. pyogenes TP8 mentioned above. The genome wide colinearity between A. haemolyticum DSM 20595 and T. pyogenes TP8 was determined by BLAST analysis at the nucleotide and amino acid levels. Then the functional similarity of these two species was analyzed by Web Gene Ontology Annotation Plot (WEGO) program (Ye et al. 2006) and by assigning the ORFs to the database of KEGG.

Genome Clustering

Genome clustering was performed based on the sequences and online program of database of Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) (http://img.jgi.doe.gov, last accessed September 29, 2014). The genome sequence of T. pyogenes TP8 sequenced here was also submitted to this database under Taxon ID 2558860978. Species of genera Mobiluncus, Actinomyces, Varibaculum, Arcanobacterium, Actinobaculum, and Trueperella were selected to generate the correlation matrix based on whole COG terms (https://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/w/main.cgi?section=EgtCluster&page=topPage, last accessed September 29, 2014). And then the data were manually processed by R packages pheatmap software (Kolde 2011) to construct the heatmap in a phylogenetic trait.

Enrichment of COG Terms and Construction of Phylogenies

The genome sequences of 1 Varibaculum cambriense, 16 Actinomyces, 4 Actinobaculum, 2 Mobiluncus, 1 A. haemolyticum DSM 20595, and 2 T. pyogenes strains were downloaded from the IMG database or NCBI, in addition to that of T. pyogenes TP8 sequenced in this study, were used to assess the common gene repertoires based on the COG ID. We consider a COG as a gene, and the common genes were selected within the rule that the same COG ID presents only once in all species. The amino acid sequences were aligned by the algorithm Prank (Löytynoja and Goldman 2005) and transferred it into phylip format by trimAl (Capella-Gutiérrez et al. 2009). Furthermore, the amino acid phylip was transformed into CDS phylip by an in house Perl script. Finally, RaxML v7.3.0 (Stamatakis 2006) was used to construct phylogenetic trees of each common gene using V. cambriense as outgroup species. Branch supports of each tree were provided by generating 1,000 bootstrap replicates. All the trees were merged by Maximum Pseudo-likelihood for Estimating Species Trees (MP-EST) in the website http://bioinformatics.publichealth.uga.edu/SpeciesTreeAnalysis/mpest/mpest.php (Liu et al. 2010). The functional divergences between clades were determined by selecting the COG terms that present in at least 80% species of each clade.

Construction of SNP tree

Combined application of software Mummer (Delcher et al. 2003) and Lastz available at http://www.bx.psu.edu/miller_lab/ (last accessed September 29, 2014) were conducted to identify the overlapped regions exist in these species, and the genome of A. haemolyticum was set as the reference. The SNP sites of each species were selected from these regions and tandem assembled to generate one sequence. The program PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al. 2010) was used to construct the ML tree with a bootstrap value of 1,000 replications in the model of HKY85.

Gene Gain and Loss

Gene content evolution in the history of Actinomycetaceae was reconstructed using COUNT software (Csuros 2010), as previously described (Yutin et al. 2009). The predicted total gene contents, gains, and losses were statistically analyzed in combination with the results of COG enrichments between clades. Each of the phylogenetic clades was tested for the enrichment of specific COG terms relative to other groups.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables S1 and S2, figures S1–S8, and data sheets S1–S3 are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online (http://www.gbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge Xuxin Li from Miyaluo Farm (Sichuan, China) for collecting the samples. This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Project: 2012CB722207) and National Forestry Bureau of China (2130211). This project was also supported by the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (grant no. 103007), National Institutes of Health (NIH) AI101973-01, and AI097532-01A1. K.Z. and B.Y. designed the work; K.Z. performed all the genome analyses and wrote the manuscript; K.Z., W.L., and L.D. performed all the bioinformatics analyses; C.K. and T.H. were associated with genome sequence verification; M.W. coordinated manuscript writing.

Literature Cited

- Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barksdale WL, Li K, Cummins CS, Harris H. The mutation of Corynebacterium pyogenes to Corynebacterium haemolyticum. J Gen Microbiol. 1957;16: 749–758. doi: 10.1099/00221287-16-3-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RE. Studies in the classification and nomenclature of bacteria. VIII: the subgroups and genera of the Actinomycetales. J Bacteriol. 1918;3:403–406. doi: 10.1128/jb.3.4.403-406.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM, Gabaldón T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MD, Jones D. Reclassification of Corynebacterium pyogenes (Glage) in the Genus Actinomyces, as Actinomyces pyogenes comb. nov. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:901–903. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-4-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MD, Jones D, Kroppenstedt RM, Schleifer KH. Chemical studies as a guide to the classification of Corynebacterium pyogenes and ‘Corynebacterium haemolyticum’. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:335–341. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-2-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MD, Jones D, Schofield GM. Reclassification of “Corynebacterium haemolyticum” (MacLean, Liebow & Rosenberg) in the genus Arcanobacterium gen. nov. as Arcanobacterium haemolyticum nom. rev., comb. nov. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:1279–1281. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-6-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csuros M. Count: evolutionary analysis of phylogenetic profiles with parsimony and likelihood. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1910–1912. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins CS, Harris H. The chemical composition of the cell wall in some Gram-positive bacteria and its possible value as a taxonomic character. J Gen Microbiol. 1956;14:583–600. doi: 10.1099/00221287-14-3-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:673–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher AL, Salzberg SL, Phillippy AM. Using MUMmer to identify similar regions in large sequence sets. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2003 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1003s00. Chapter 10:Unit 10.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher J, Francke C, Postma PW. How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:939–1031. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00024-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke G, Englert R, Frodl R, Bernard KA, Stenger S. Actinomyces hominis sp. nov., isolated from a wound swab. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:1678–1681. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.015818-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone RJ, et al. Draft genome sequence of Trueperella pyogenes, isolated from the infected uterus of a postpartum cow with metritis. Genome Announc. 2014;2(2):e00194–14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00194-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha S, Goyal SP, Kashyap VK. Molecular phylogeny of musk deer: a genomic view with mitochondrial 16S rRNA and cytochrome b gene. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;42:585–597. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall V, et al. Characterization of some Actinomyces-like isolates from human clinical sources: description of Varibaculum cambriensis gen. nov., sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:640–644. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.640-644.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolde R. 2011 pheatmap: pretty heatmaps. R package version 0.7.7. Available from: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson PA, Falsen E, Åkervall E, Vandamme P, Collins MD. Characterization of some Actinomyces-like isolates from human clinical specimens: reclassification of Actinomyces suis (Soltys and Spratling) as Actinobaculum suis comb. nov. and description of Actinobaculum schaalii sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:899–903. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Yu L, Edwards SV. A maximum pseudo-likelihood approach for estimating species trees under the coalescent model. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löytynoja A, Goldman N. An algorithm for progressive multiple alignment of sequences with insertions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10557–10562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409137102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado VS, Bicalho RC. Complete genome sequence of Trueperella pyogenes, an important opportunistic pathogen of livestock. Genome Announc. 2014;2(2):e00400–14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00400-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos CP, Foster G, Collins MD. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Actinomyces based on 16S rRNA gene sequences: description of Arcanobacterium phocae sp. nov., Arcanobacterium bernardiae comb. nov., and Arcanobacterium pyogenes comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47: 46–53. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-1-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards VP, et al. Phylogenomics and the dynamic genome evolution of the genus streptococcus. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:741–753. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaal KP, Yassin AF, Stackebrandt E. The family Actinomycetaceae: the genera Actinomyces, Actinobaculum, Arcanobacterium, Varibaculum, and Mobiluncus. In: Balows A, Tru�per HG, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer KH, editors. The prokaryotes: a handbook on the biology of bacteria: ecophysiology, isolation, identification, applications. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 850–905. [Google Scholar]

- Slack JM. Family Actinomycetaceae Buchanan 1918 and genus Actinomyces Harz 1877. In: Buchanan RE, Gibbons NE, editors. Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology. 8th ed. Baltimore (MD): Williams & Wilkins; 1974. pp. 659–667. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel CA, Roberts M. Mobiluncus gen. nov., Mobiluncus curtisii subsp. curtisii sp. nov., Mobiluncus curtisii subsp. holmesii subsp. nov., and Mobiluncus mulieris sp. nov., curved rods from the human vagina. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1984;34:177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:479–491. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard P, Wishart DS. Circular genome visualization and exploration using CGView. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:537–539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasawong M, et al. Complete genome sequence of Arcanobacterium haemolyticum type strain (11018) Stand Genomic Sci. 2010;3(2):126–135. doi: 10.4056/sigs.1123072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassin AF, Hupfer H, Siering C, Schumann P. Comparative chemotaxonomic and phylogenetic studies on the genus Arcanobacterium Collins et al. 1982 emend. Lehnen et al. 2006: proposal for Trueperella gen. nov. and emended description of the genus Arcanobacterium. Int J Syst Evol Micrbiol. 2011;61:1265–1274. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.020032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, et al. WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl031. 34(Web Server issue):W293–W297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yutin N, Wolf YI, Raoult D, Koonin EV. Eukaryotic large nucleo-cytoplasmic DNA viruses: clusters of orthologous genes and reconstruction of viral genome evolution. Virol J. 2009;6:223. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K, et al. Detection and characterization of antibiotic resistance genes in Arcanobacterium pyogenes strains from abscesses of forest musk deer. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:1820–1826. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.033332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:589–608. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.