Abstract

Accumulating experimental evidence indicates that overexpression of the oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinase, Axl, plays a key role in the tumorigenesis and metastasis of various types of cancer. The objective of this study is to design a novel imaging probe based on the monoclonal antibody, h173, for microPET imaging of Axl expression in human lung cancer. A bifunctional chelator, DOTA, was conjugated to h173, followed by radiolabeling with 64Cu. The binding of DOTA-h173 to the Axl receptor was first evaluated by a cell uptake assay and flow cytometry analysis using human lung cancer cell lines. The probe 64Cu-DOTA-h173 was further evaluated by microPET imaging, and ex vivo histology studies in the Axl-positive A549 tumors. In vitro cellular study showed that Axl probe, 64Cu-DOTA-h173, was highly immuno-reactive with A549 cells. Western blot analysis confirmed that Axl is highly expressed in the A549 cell line. For microPET imaging, the A549 xenografts demonstrated a significantly higher 64Cu-DOTA-h173 uptake compared to the NCI-H249 xenograft (a negative control model). Furthermore, 64Cu-DOTA-h173 uptake in A549 is significantly higher than that of 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG. Immuno-fluorescence staining was consistent with the in vivo micro-PET imaging results. In conclusion, 64Cu-DOTA-h173 could be potentially used as a probe for noninvasive imaging of Axl expression, which could collect important information regarding tumor response to Axl-targeted therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Axl receptor, monoclonal antibody, positron emission tomography (PET), lung cancer

Introduction

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are a class of protein kinases that play a critical role in the development and progression of various types of cancer. Recently, approximately 20 different RTK classes have been identified, with Axl belonging to one of these classes.1,2 The Axl receptor tyrosine kinase was isolated as a transforming gene from primary human myeloid leukemia cells.3 Axl is implicated in vascular remodeling, regulation of smooth muscle cells, and migration of endothelial cells.4−6 In recent years, the significant role of Axl in tumor initiation and metastases has been reinforced by the fact that Axl is overexpressed in multiple cancer types including prostate,7 breast,8−10 lung,11−15 gastric,16 glioblastoma,17,18 and Kaposi sarcoma.19 Several studies also indicate that the expression level of Axl is highly correlated with lung tumor progression15 and invasiveness of breast cancer cells.10 In addition, Axl is identified as a potential therapeutic target for overcoming EGFR inhibitor resistance11 and for lapatinib and trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer cells.8

In order to hasten the pace of developing anti-Axl based cancer therapy for clinical trials, it is desirable to establish effective methods to quantify Axl expression in vivo. Molecular imaging techniques have been widely used for diagnosis and therapy management through evaluation of molecular marker and receptor expression in vivo. In particular, positron emission tomography (PET) has gained a remarkable amount of attention due to its quantitative imaging properties and high sensitivity. In fact, there is a considerable amount of interest in development of imaging probes for PET that can serve as companion diagnostics for novel therapeutics. However, to the best of our knowledge, no PET probe targeting Axl has been reported in previous literature.

Recently, monoclonal antibodies of murine origin that are specific for Axl have been developed. One of these antibodies, m173, appears to bind to the first fibronection domain.19 To enhance clinical application, humanized 173 (h173) was also produced as reported.20 Because of the strong and specific binding of h173 to Axl, we hypothesized that radiolabeled h173 could depict the Axl receptor distribution in vivo by PET. The data obtaining by PET imaging could be used to confirm the presence of Axl, which would be important clinical information in determining the utility of Axl-targeted chemo- and radiotherapy in receptor positive patients. In this study, we radiolabeled h173 with 64Cu to create an antibody based PET probe to noninvasively quantify Axl expression in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) Analysis

Human small cell lung cancer A549 cell line and nonsmall cell lung cancer cell line NCI-H249, obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. For FACS analysis, adherently grown A549 cells were detached by applying nonenzymatical citric saline buffer.21 NCI-H249 cells were grown in suspension. To minimize nonspecific uptake, the procedures were performed on ice. Aliquots of cells were blocked with 10% normal goat serum, incubated with anti-Axl primary antibody h173 (kindly provided by Vasgene Therapeutics Inc., Los Angeles, CA) produced using composite human antibody technology20 and goat antihuman Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Paisley, Scotland) in sequence. Subsequently, cells were measured by flow cytometry (CyAn analyzer, Beckman Coulter). Cells without the incubation of primary antibody were used as negative controls.

Western Blot

A Western blot was performed as described previously.22,23 Proteins extracted from A549 and NCI-H249 tumor cells were fractionated using 4–20% SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad). After protein transfer, polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk, probed with anti-Axl primary antibody (Cat #8661, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and secondary antibody, and developed. β-actin was used as an internal control.

Chemistry and Radiochemistry

h173 was conjugated with DOTA-NHS synthesized in situ (molar ratio, 1:20) through amino groups to form DOTA-h173. The synthesis followed literature reported procedures.23 Negative control antibody, human normal immunoglobulin G (hIgG), was purchased from Rockland (Gilbertsville, PA). Control probe DOTA-hIgG was also synthesized using the same procedure. After 64Cu (purchased from Washington University, St. Louis) labeling,23 probes were used for further in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Binding Activity Assay

Axl binding activity of DOTA-h173 and DOTA-hIgG was performed through a bead-based binding assay with Axl-alkaline phosphatase (AP) (kindly provided by Vasgene Therapeutics Inc., Los Angeles, CA) as reported previously.22,23 Each sample was repeated in triplicate.

Cell Uptake Assay

Cell uptake of probes in A549 and NCI-H249 tumor cells was performed as described previously.24 Adherently grown A549 cells were harvested by applying nonenzymatical citric saline buffer.21 NCI-H249 cells were grown in suspension. 5 × 105 cells were suspended in 200 μL of complete cell culture media, and 37 kBq of 64Cu-DOTA-h173 and 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG was added. After 1.5 h of incubation, unbound probes were removed by washing twice with cold PBS. Finally, cells were sedimented by centrifugation, and the radioactivity in each cell pellet was counted. The data were obtained in triplicate.

Tumor Xenografts and microPET Imaging

All animal experiments were performed under a protocol approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). To establish a lung tumor xenograft model, 2 × 106 of A549 or NCI-H249 cells were subcutaneously injected in the right shoulder of nude mice as previous reported.22,23

The tumor-bearing mice were injected with 3.7–7.4 MBq of 64Cu probes via tail veins. For each probe, 3 randomly selected mice were used. Multiple static scans were obtained at 3, 16, 28, and 45 h postinjection (p.i.). PET imaging and analysis were conducted by using a Siemens microPET R4 rodent model scanner as described previously.23,25

Immunofluorescence Staining

Antibody distribution was evaluated through immunofluorescence staining as previously reported.23 Tumors were dissected at 48 h p.i. of 30 μg of DOTA-h173 or DOTA-hIgG. Antibody distribution was localized by using secondary antibody goat antihuman Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen, Paisley, Scotland).

Statistical Analysis

All of the quantitative data are given as means ± SD of three independent measurements. Student’s t-test was used to analyze the data. Statistical significance was assigned for P values < 0.05.

Results

Chemistry, Radiochemistry, and Binding Activity Assay

h173 and hIgG were conjugated with 64Cu chelator DOTA through amino groups, which lead to DOTA-h173 and DOTA-hIgG. After 64Cu labeling, the radiochemical yields for 64Cu-DOTA-h173 and 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG were 44.5% and 57.6%, respectively. The specific activity of 64Cu-DOTA-h173 and 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG was estimated to be 1.48–2.96 GBq/mg antibody. To investigate the influence of DOTA conjugation on Axl binding ability, a binding activity assay was conducted. Axl binding activity was preserved with DOTA-h173 (98.27% ± 1.29%). On the contrary, DOTA-hIgG showed 0.015 ± 0.003% binding activity toward this target.

Axl Expression Assay on Cell Lines and Cell Uptake Study

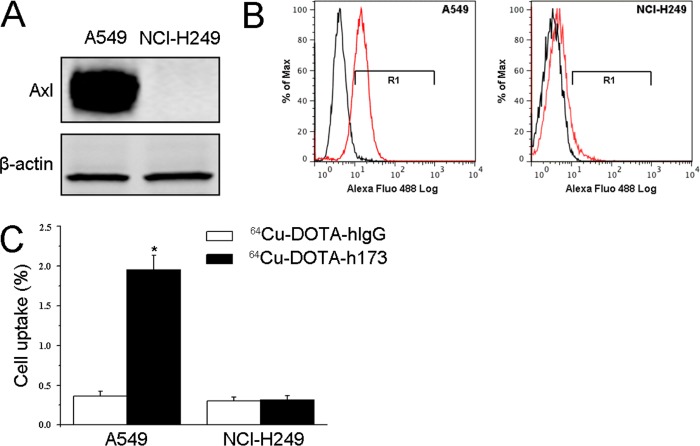

We used A549 and NCI-H249 human lung cancer cell lines for this study. A Western blot was performed to detect Axl expression in these two cell lines. As shown in Figure 1A, A549 overexpressed Axl, while NCI-H249 was negative. Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorting (FACS) data demonstrated that the percentage of Axl positive in A549 and NCI-H249 was 84.40 ± 1.56% and 2.43 ± 0.27%, respectively (Figure 1B). Cell uptake study was also conducted (Figure 1C). In A549 cells, the cell uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-h173 (1.96 ± 0.10%) was significantly higher than 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG (0.36 ± 0.04%) (P < 0.05). The cell uptake of both 64Cu-DOTA-h173 (0.32 ± 0.05%) and 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG (0.30 ± 0.05%) in NCI-H249 cells was low and showed no significant difference between them (P > 0.05). The above in vitro data demonstrated that 64Cu-DOTA-h173 probe was Axl-specific.

Figure 1.

(A) Western blot of Axl in A549 and NCl-H249 tumor cells. (B) FACS analysis of A549 and NCl-H249 tumor cells using h173 as the primary antibody. (C) Cell uptake assay of 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG and 64Cu-DOTA-h173 on A549 and NCl-H249 tumor cells (n = 3, mean ± SD).

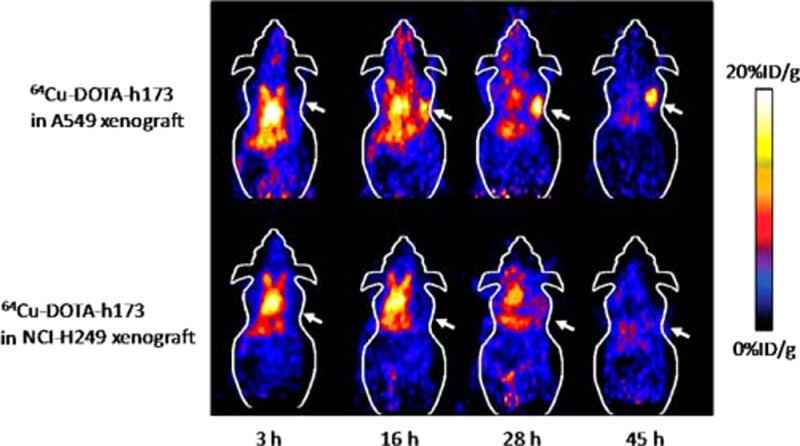

In Vivo MicroPET Imaging Study

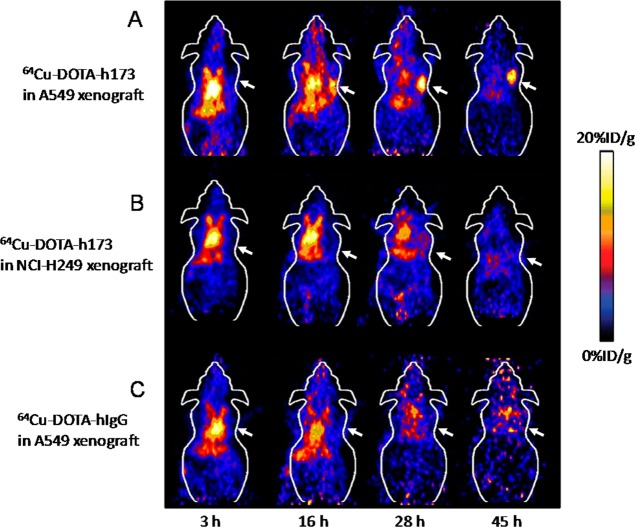

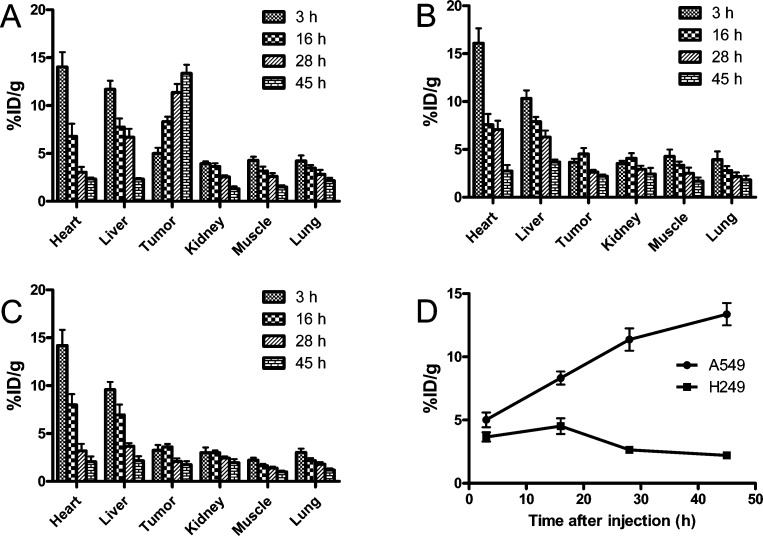

The in vivo microPET imaging study was performed on both A549 and NCI-H249 tumor xenograft mice after the injection of 64Cu-DOTA-h173 or 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG. Representative decay-corrected coronal images are shown in Figure 2. At an early time point, both 64Cu-DOTA-h173 and 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG demonstrated high heart uptake because of the relative long circulation half-life of antibodies in vivo. Similarly, the liver also had relatively high uptake, which could be attributed to the nonspecific uptake of tracers through the reticular-endothelial system. As for other organs, such as the lung, their uptake was not significantly different from the background such as muscle. The uptake in the tumor or other organs was calculated from the ROI analysis and shown in Figure 3. The A549 tumor uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-h173 was 5.02 ± 1.00, 8.32 ± 0.89, 11.37 ± 1.53, and 13.37 ± 1.53 %ID/g (percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue) at 3, 16, 28, and 45 h p.i., respectively. The NCI-H249 tumor uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-h173 was 3.66 ± 0.64, 4.52 ± 1.08, 2.65 ± 0.36, and 2.21 ± 0.30 %ID/g at 3, 16, 28, and 45 h p.i., respectively. 64Cu-DOTA-h173 uptake in A549 tumors was significantly higher than in NCI-H249 tumors (P < 0.05, Figure 3D) at 16, 28, and 45 h time points. The A549-tumor to lung ratios were 1.21 ± 0.25, 2.42 ± 0.36, 4.35 ± 1.80, and 6.53 ± 2.10 %ID/g at 3, 16, 28, and 45 h p.i. of 64Cu-DOTA-h173, respectively. 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG was also imaged in A549 tumor models to validate the target specificity of 64Cu-DOTA-h173. The A549 tumor uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG at all time points examined was comparatively low (3.26 ± 0.94, 3.59 ± 0.54, 2.09 ± 0.55, and 1.76 ± 0.58 %ID/g at 3, 16, 28, and 45 h p.i., respectively), which is similar to the muscle uptake (4.28 ± 1.23, 3.35 ± 0.65, 2.52 ± 0.98, and 1.69 ± 0.66 %ID/g at 3, 16, 28, and 45 h p.i., respectively).

Figure 2.

Decay-corrected whole-body coronal microPET images from a static scan at 3, 16, 28, and 45 h p.i. of (A) 64Cu-DOTA-h173 into A549 tumor bearing mice, (B) 64Cu-DOTA-h173 into NCl-H249 tumor bearing mice, and (C) 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG into A549 tumor bearing mice. Arrows indicate tumors.

Figure 3.

Major organ radioactivity accumulation quantification from a static scan at 3, 16, 28, and 45 h p.i. of (A) 64Cu-DOTA-h173 into A549 tumor bearing mice, (B) 64Cu-DOTA-h173 into NCl-H249 tumor bearing mice, and (C) 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG into A549 tumor bearing mice. (D) Time course of A549 and NCl-H249 tumor uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-h173 from 3 to 45 h p.i.

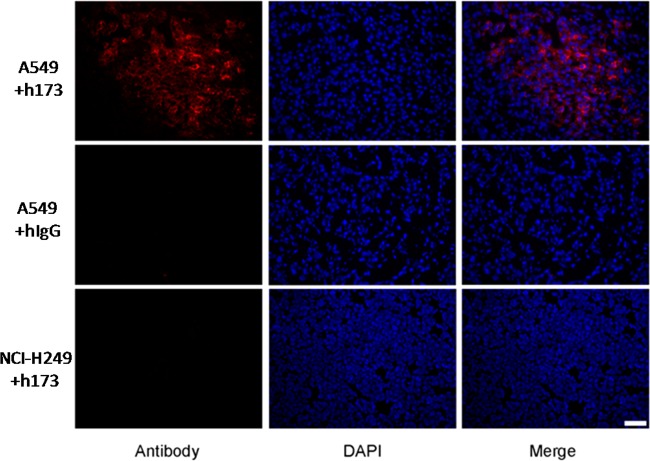

Probe Distribution Analysis in Tumor Tissues

Probe distribution analysis in tumor tissues was conducted through immunofluorescence staining. As shown in Figure 4, more h173 accumulated in Axl-positive A549 tumors than hIgG control. In Axl-negative NCI-H249 tumors, there was minimal accumulation of h173. Therefore, both in vitro and in vivo data indicated that 64Cu-DOTA-h173 could be applied for noninvasive imaging of Axl expression.

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescence staining of antibodies in A549 and NCl-H249 tumor sections. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Discussion

Up until now, 20 distinct subfamilies of RTKs have been found and categorized according to their identities in their amino acid sequence and structural similarities in their extracellular regions. One of these, the subfamily TAM, is composed of Axl, Sky, and Mer. Axl and its ligand, Gas6, have been found to play a pivotal role in the survival and metastasis of multiple cancers and other diseases.7,16,26−30

In this study, the novel 64Cu-labeled h173 antibody was synthesized and characterized to demonstrate that imaging Axl expression with PET is possible. Attachment of 64Cu to a targeting molecule required the use of a bifunctional chelator (BFC). In our experiment, the chelator used was commercially available DOTA. Binding activity assay showed that DOTA-h173 preserved 98.27% ± 1.29% Axl binding activity. FACS (Figure 1B) and the cell uptake study (Figure 1C) further confirmed that h173 could bind to Axl-positive A549 lung cancer cells, but not to Axl-negative NCI-H249 tumors, indicating that h173 antibody was Axl-specific. Western detects both cell surface and cytoplasm Axl while flow cytometry detects only cell surface Axl. Therefore, the receptor expression difference in flow cytometry was not as drastic as the western data.

The in vivo microPET imaging study was performed on both A549 and NCI-H249 tumor xenograft mice (Figures 2 and 3). 64Cu-DOTA-h173 uptake in A549 tumors increased with time, and a better tumor-to-background contrast was displayed at late time points (28 h, 45 h p.i.). Both active uptake (contributed by h173-Axl interaction) and passive uptake (contributed by the enhanced permeability and retention effect) lead to 64Cu-DOTA-h173 accumulation in A549 tumors. In contrast, tumor accumulation of 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG was only caused by passive uptake. The A549 tumor uptake of 64Cu-DOTA-hIgG at all time points examined was comparatively low. Thus, the target specificity of 64Cu-DOTA-h173 was confirmed. On the contrary, 64Cu-DOTA-h173 uptake in NCI-H249 tumors was significantly lower than in A549 tumors (P < 0.05, Figure 3D). As h173 only recognizes human Axl, it does not target murine vasculature, which also expresses Axl in tumor xenograft mouse models, according to the published studies.31,32 Therefore, the difference in tumor uptake should reflect the Axl expression levels of different lung tumor cells. We would like to point out that tumors without Axl expression could still show some tracer uptake due to the presence of nonspecific accumulation. In order to accurately reflect Axl receptor expression level with immunoPET, the contribution from “passive” targeting needs to be considered during data analysis. However, in humans, use of 64Cu-DOTA-h173 for Axl-targeted imaging might provide higher contrast from surrounding tissues due to the fact that it recognizes both tumor cells and associated vasculature. In addition, highly selective localization of h173 to the tumor bed could lead to applications with therapeutic radionuclides, such as 90Y, 177Lu, or 213Bi for targeted radiation therapy.33

Conclusions

We have developed a receptor-targeted PET probe for detection of Axl-positive tumors. This study shows that 64Cu-DOTA-h173, based on a humanized Axl-specific monoclonal antibody, displays high target specificity both in vitro and in vivo. The positive correlation between Axl expression levels and tumor invasiveness in multiple cancer types makes 64Cu-DOTA-h173 potentially clinically useful for staging Axl-positive cancers and managing patients with Axl-targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIBIB (R21 1 r21 eb012294-01a1 and 1R01EB014354-01A1), Early (Margaret E.) Medical Research Trust, the American Cancer Society (121991-MRSG-12-034-01-CCE), SC CTSI (12-2176-3135), Department of Defense (BC102678), Vasgene Therapeutics Inc. (NIH: CA168158-01 and CA171538-01), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U1032002, 81071206, 81271621, and 81301266), and Key Clinical Research Project of Public Health Ministry of China 2010-2012 (No. 164).

Author Contributions

# S.L., D.L., and J.G. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Hafizi S.; Dahlback B. Signalling and functional diversity within the Axl subfamily of receptor tyrosine kinases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006, 17, 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafizi S.; Dahlback B. Gas6 and protein S. Vitamin K-dependent ligands for the Axl receptor tyrosine kinase subfamily. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 5231–5244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Bryan J. P.; Frye R. A.; Cogswell P. C.; Neubauer A.; Kitch B.; Prokop C.; Espinosa R. 3rd; Le Beau M. M.; Earp H. S.; Liu E. T. Axl, a transforming gene isolated from primary human myeloid leukemia cells, encodes a novel receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991, 11, 5016–5031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melaragno M. G.; Fridell Y. W.; Berk B. C. The Gas6/Axl system: a novel regulator of vascular cell function. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 1999, 9, 250–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korshunov V. A.; Mohan A. M.; Georger M. A.; Berk B. C. Axl, a receptor tyrosine kinase, mediates flow-induced vascular remodeling. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 1446–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collett G. D.; Sage A. P.; Kirton J. P.; Alexander M. Y.; Gilmore A. P.; Canfield A. E. Axl/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling inhibits mineral deposition by vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 502–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainaghi P. P.; Castello L.; Bergamasco L.; Galletti M.; Bellosta P.; Avanzi G. C. Gas6 induces proliferation in prostate carcinoma cell lines expressing the Axl receptor. J. Cell. Physiol. 2005, 204, 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Greger J.; Shi H.; Liu Y.; Greshock J.; Annan R.; Halsey W.; Sathe G. M.; Martin A.-M.; Gilmer T. M. Novel mechanism of lapatinib resistance in HER2-positive breast tumor cells: Activation of AXL. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 6871–6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjerdrum C.; Tiron C.; Høiby T.; Stefansson I.; Haugen H.; Sandal T.; Collett K.; Li S.; McCormack E.; Gjertsen B. T.; Micklem D. R.; Akslen L. A.; Glackin C.; Lorens J. B. Axl is an essential epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-induced regulator of breast cancer metastasis and patient survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 1124–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.-X.; Knyazev P. G.; Cheburkin Y. V.; Sharma K.; Knyazev Y. P.; Őrfi L.; Szabadkai I.; Daub H.; Kéri G.; Ullrich A. AXL is a potential target for therapeutic intervention in breast cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 1905–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers L. A.; Diao L.; Wang J.; Saintigny P.; Girard L.; Peyton M.; Shen L.; Fan Y.; Giri U.; Tumula P. K.; Nilsson M. B.; Gudikote J.; Tran H.; Cardnell R. J. G.; Bearss D. J.; Warner S. L.; Foulks J. M.; Kanner S. B.; Gandhi V.; Krett N.; Rosen S. T.; Kim E. S.; Herbst R. S.; Blumenschein G. R.; Lee J. J.; Lippman S. M.; Ang K. K.; Mills G. B.; Hong W. K.; Weinstein J. N.; Wistuba I. I.; Coombes K. R.; Minna J. D.; Heymach J. V. An epithelial–mesenchymal transition gene signature predicts resistance to EGFR and PI3K inhibitors and identifies axl as a therapeutic target for overcoming EGFR inhibitor resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 279–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postel-Vinay S.; Ashworth A. AXL and acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 835–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan C. A.; Singh S.; Windle B.; Yeudall W. A.; Frum R.; Grossman S. R.; Deb S. P.; Deb S. Gain-of-function activity of mutant p53 in lung cancer through up-regulation of receptor protein tyrosine kinase Axl. Genes Cancer 2012, 3, 491–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M.; Sonobe M.; Nakayama E.; Kobayashi M.; Kikuchi R.; Kitamura J.; Imamura N.; Date H. Higher expression of receptor tyrosine kinase Axl, and differential expression of its ligand, Gas6, predict poor survival in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, Suppl 3, S467–S476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh Y. S.; Lai C. Y.; Kao Y. R.; Shiah S. G.; Chu Y. W.; Lee H. S.; Wu C. W. Expression of axl in lung adenocarcinoma and correlation with tumor progression. Neoplasia 2005, 7, 1058–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. W.; Li A. F.; Chi C. W.; Lai C. H.; Huang C. L.; Lo S. S.; Lui W. Y.; Lin W. C. Clinical significance of AXL kinase family in gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2002, 22, 1071–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutterer M.; Knyazev P.; Abate A.; Reschke M.; Maier H.; Stefanova N.; Knyazeva T.; Barbieri V.; Reindl M.; Muigg A.; Kostron H.; Stockhammer G.; Ullrich A. Axl and growth arrest-specific gene 6 are frequently overexpressed in human gliomas and predict poor prognosis in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vajkoczy P.; Knyazev P.; Kunkel A.; Capelle H.-H.; Behrndt S.; von Tengg-Kobligk H.; Kiessling F.; Eichelsbacher U.; Essig M.; Read T.-A.; Erber R.; Ullrich A. Dominant-negative inhibition of the Axl receptor tyrosine kinase suppresses brain tumor cell growth and invasion and prolongs survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 5799–5804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Gong M.; Li X.; Zhou Y.; Gao W.; Tulpule A.; Chaudhary P. M.; Jung J.; Gill P. S. Induction, regulation, and biologic function of Axl receptor tyrosine kinase in Kaposi sarcoma. Blood 2010, 116, 297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnoperov V.; Kumar S. R.; Ley E.; Li X.; Scehnet J.; Liu R.; Zozulya S.; Gill P. S. Novel EphB4 monoclonal antibodies modulate angiogenesis and inhibit tumor growth. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 176, 2029–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Shan H.; Li D.; Li Z. R.; Zhu K. S.; Jiang Z. B.; Huang M. S. Different methods of detaching adherent cells significantly affect the detection of TRAIL receptors. Tumori 2012, 98, 800–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Liu S.; Liu R.; Park R.; Hughes L.; Krasnoperov V.; Gill P. S.; Li Z.; Shan H.; Conti P. S. Targeting the EphB4 receptor for cancer diagnosis and therapy monitoring. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 10, 329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Li D.; Park R.; Liu R.; Xia Z.; Guo J.; Krasnoperov V.; Gill P. S.; Li Z.; Shan H.; Conti P. S. PET imaging of colorectal and breast cancer by targeting EphB4 receptor with 64Cu-labeled hAb47 and hAb131 antibodies. J. Nucl. Med. 2013, 54, 1094–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Li D.; Shan H.; Gabbai F. P.; Li Z.; Conti P. S. Evaluation of (18)F-labeled BODIPY dye as potential PET agents for myocardial perfusion imaging. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2014, 41, 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Li D.; Huang C. W.; Yap L. P.; Park R.; Shan H.; Li Z.; Conti P. S. Efficient construction of PET/fluorescence probe based on sarcophagine cage: an opportunity to integrate diagnosis with treatment. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2012, 14, 718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammoun S.; Provenzano L.; Zhou L.; Barczyk M.; Evans K.; Hilton D. A.; Hafizi S.; Hanemann C. O. Axl/Gas6/NFkappaB signalling in schwannoma pathological proliferation, adhesion and survival. Oncogene 2014, 33, 336–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman C.; Jönsen A.; Sturfelt G.; Bengtsson A. A.; Dahlbäck B. Plasma concentrations of Gas6 and sAxl correlate with disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2011, 50, 1064–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson A.; Martuszewska D.; Johansson M.; Ekman C.; Hafizi S.; Ljungberg B.; Dahlback B. Differential expression of Axl and Gas6 in renal cell carcinoma reflecting tumor advancement and survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 4742–4749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson A.; Bostrom A. K.; Ljungberg B.; Axelson H.; Dahlback B. Gas6 and the receptor tyrosine kinase Axl in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. PLoS One 2009, 4, e7575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W.; Fujimoto J.; Tamaya T. Coexpression of Gas6/Axl in human ovarian cancers. Oncology 2004, 66, 450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutterer M.; Knyazev P.; Abate A.; Reschke M.; Maier H.; Stefanova N.; Knyazeva T.; Barbieri V.; Reindl M.; Muigg A.; Kostron H.; Stockhammer G.; Ullrich A. Axl and growth arrest-specific gene 6 are frequently overexpressed in human gliomas and predict poor prognosis in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensi M.; Catani M.; Castellano G.; Nicolini G.; Alciato F.; Tragni G.; De Santis G.; Bersani I.; Avanzi G.; Tomassetti A.; Canevari S.; Anichini A. Human cutaneous melanomas lacking MITF and melanocyte differentiation antigens express a functional Axl receptor kinase. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 2448–2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H.; Sgouros G. Radioimmunotherapy of solid tumors: searching for the right target. Curr. Drug Delivery 2011, 8, 26–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]