Abstract

Purpose.

To identify the cause of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in UTAD003, a large, six-generation Louisiana family with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adRP).

Methods.

A series of strategies, including candidate gene screening, linkage exclusion, genome-wide linkage mapping, and whole-exome next-generation sequencing, was used to identify a mutation in a novel disease gene on chromosome 10q22.1. Probands from an additional 404 retinal degeneration families were subsequently screened for mutations in this gene.

Results.

Exome sequencing in UTAD003 led to identification of a single, novel coding variant (c.2539G>A, p.Glu847Lys) in hexokinase 1 (HK1) present in all affected individuals and absent from normal controls. One affected family member carries two copies of the mutation and has an unusually severe form of disease, consistent with homozygosity for this mutation. Screening of additional adRP probands identified four other families (American, Canadian, and Sicilian) with the same mutation and a similar range of phenotypes. The families share a rare 450-kilobase haplotype containing the mutation, suggesting a founder mutation among otherwise unrelated families.

Conclusions.

We identified an HK1 mutation in five adRP families. Hexokinase 1 catalyzes phosphorylation of glucose to glucose-6-phosphate. HK1 is expressed in retina, with two abundant isoforms expressed at similar levels. The Glu847Lys mutation is located at a highly conserved position in the protein, outside the catalytic domains. We hypothesize that the effect of this mutation is limited to the retina, as no systemic abnormalities in glycolysis were detected. Prevalence of the HK1 mutation in our cohort of RP families is 1%.

Keywords: retinitis pigmentosa, hexokinase, inherited retinal dystrophy

Mutations in a novel gene, hexokinase 1 (HK1), account for 1% of cases of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa.

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a group of inherited dystrophic disorders of the retina leading to profound loss of vision or blindness. The clinical hallmarks of RP are night blindness, followed by progressive loss of peripheral vision, often culminating in complete blindness. Clinical findings of RP include “bone spicule” pigmentary deposits, retinal vessel attenuation, and characteristic changes in the electroretinograms (ERG).1

Retinitis pigmentosa affects approximately 1 in 4000 people in the United States, Europe, and Japan. Retinitis pigmentosa is exceptionally heterogeneous with many different genes implicated, many different disease-causing mutations in each gene, and varying clinical presentations even among members of the same family.2 For nonsyndromic RP, mutations in 24 genes are known to cause autosomal dominant RP (adRP); 45 genes cause recessive RP (arRP), and 3 genes cause X-linked RP (summarized in RetNet, https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/ [in the public domain]).

The genes found to date as causes of adRP do not fall into a single functional category but include a diverse range of retinal functions, including components of the phototransduction cycle (RHO, GUCA1A, RDH12); pre-mRNA processing factors (PRPF3, PRPF4, PRPF6, PRPF8, PRPF31, SNRNP200); structural proteins (PRPH2, ROM1); ciliary proteins (RP1, TOPORS); transcription factors (NRL, CRX, NR2E3); and a seemingly random assortment of other genes (BEST1, CA4, FSCN2, IMPDH1, KLHL7, RPE65, SEMA4A). With current techniques, we can identify likely disease-causing mutations in approximately 75% of patients with adRP (Daiger SP, manuscript in preparation, 2014). While mutations in some known genes may be missed, a number of additional adRP genes remain to be identified. In our University of Texas (UT) adRP cohort, mutations have been found in 205 of 265 families, leaving 60 (23%) with potentially novel adRP genes.

Materials and Methods

Patient Collections and DNA Isolation

This research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from each of the individuals examined and tested. This study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and by the respective human subjects' Review Boards at each of the participating institutions.

The UTAD003 family was ascertained in 1990 and was one of the first large families in the UT adRP cohort.3 The inherited retinal dystrophy in this family can be traced back to the early 1800s, to an Acadian ancestor living in the same part of south-central Louisiana where the family still resides. Blood or saliva samples were obtained from 19 family members (Fig. 1), most of whom are affected or at risk, and DNA was isolated as described previously.3

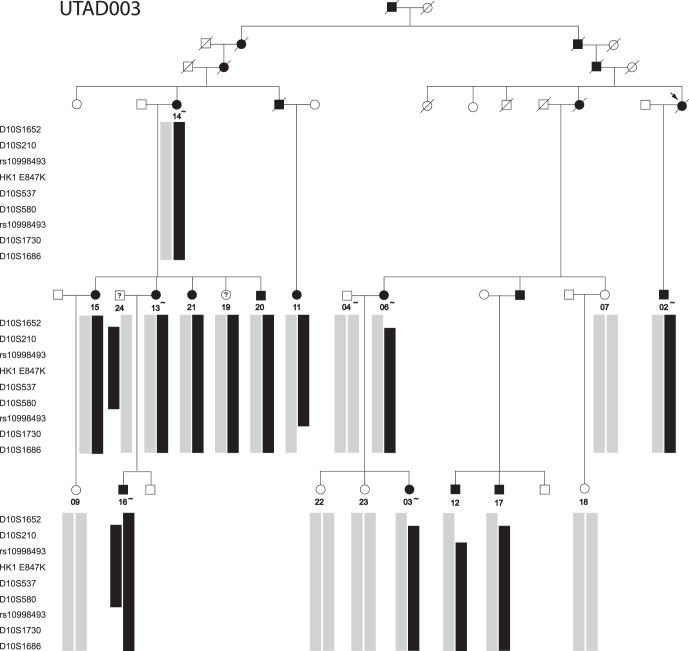

Figure 1.

AdRP family UTAD003. Filled symbols indicate diagnosis of adRP. Individuals for whom DNA samples are available are indicated with numbers; samples on which whole-exome sequencing was performed are indicated with tilde. Symbols with a question mark indicate patients without a definitive diagnosis and unavailable for follow-up. Black bars indicate the chromosome 10 haplotypes linked to disease. Gray bars indicate a variety of nondisease chromosome haplotypes.

The UT adRP patient cohort contains 265 families with a high likelihood of autosomal dominant inheritance. One affected individual from each family had been tested previously for mutations in the (currently) known adRP genes. The 60 cohort families without previously identified mutations were tested in this study.4,5 An additional 428 retinal dystrophy patients sent to the Laboratory for the Molecular Diagnosis of Inherited Eye Diseases, UT Houston, were tested also.3,6,7 Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood as reported previously.3 Saliva was collected with Oragene collection kits (DNA Genotek, Inc., Kanata, ON, Canada) and extracted according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol. Families and patients were largely Americans of European origin and Europeans.

Exclusion of Known adRP Genes

Two affected individuals from the UTAD003 family were tested for possible mutations in the known adRP genes with fluorescent dideoxy sequencing as described previously.3–5,8–10 Linkage-exclusion analysis in the UTAD003 family was completed by short tandem repeat (STR) markers flanking the known adRP genes and related disease loci. Short tandem repeat genotypes were determined and linkage was performed with the LINKAGE package.11 DNA samples from two affected members of the UTAD003 family were tested for mutations in all known retinal disease–associated genes (RetNet) by PCR product and/or oligo-capture next-generation sequencing (NGS).12,13

Whole Genome Linkage

Genomic DNAs from nine affected, six unaffected at risk, and one unaffected member of the UTAD003 family were genotyped at the University of California at Los Angeles Sequencing and Genotyping Center with an ABI High Density 5cM STR marker set (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). Genotyping data from the 811 STR markers were analyzed with the LINKAGE package as described previously.11,14

Exome Sequencing

Exome capture used a customized Agilent SureSelect All Exome Kit v.2.0 (Wilmington, DE, USA) (four samples) or the Nimblegen SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library v.2.0 (Roche, Madison, WI, USA) (four samples) according to the manufacturers' protocols. Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) paired-end sequencing (2× 100 bp), alignment, and variant calling were performed as described previously.15

HK1 Analyses

The hexokinase 1 (HK1) exome variant was typed by amplification and fluorescent dideoxy sequencing with PCR primers that flank exon 23 (Supplementary Table S1). All additional coding and noncoding exons and flanking intron/exon junctions of the HK1 gene were sequenced by standard methods and the primers in Supplementary Table S1. Sequence data were analyzed with SeqScape v.3 and Sequencing Analysis Software v6 (Life Technologies). The logarithm of the odds (LOD) scores were calculated for the UTAD003 family and the HK1 mutation with VITESSE.16

Haplotyping With STRs and SNPs

Short tandem repeat markers were selected from the ABI linkage mapping set or the UCSC database (http://genome.ucsc.edu/index.html [in the public domain]). Genomic DNA was amplified, separated, and genotyped as described previously.17 Intragenic and flanking single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were genotyped by standard fluorescent dideoxy sequencing.5

Glucose-6-Phosphate Levels and RBC Morphology in Serum of Patients and Controls

We performed a glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) assay in affected individuals and family members from the MOGL1 family. Intracellular G6P levels in red blood cells (RBCs) were measured by colorimetric assay using the commercially available kit from Abcam (ab83426; Cambridge, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, approximately 4 mL fresh venous blood was collected from each of the subjects in red-topped tubes. Red blood cell pellets were obtained after allowing the blood to clot by leaving the samples undisturbed at room temperature for 30 minutes. The clot was removed by centrifuging the samples at 1000g to 2000g for 10 minutes in a refrigerated centrifuge. The resulting supernatant (the serum) was maintained at 2°C to 8°C during handling and was stored at −20°C. Samples were filtered through 10-kD spin columns (ab93349; Abcam). Samples (50 μL per time point per biological replicate) were processed following the instructions, and all samples were processed in a single run to enhance quantification and comparability. Colorimetric measurements were made at 25°C using optical density (OD)450 measurements on an Epoch microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA). We performed three technical replicates for each sample.

Bioinformatics

The NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server,18 1000 Genomes database,19 and dbSNP20 were searched for the presence of the HK1 p.Glu847Lys variant. SIFT,21 PolyPhen-2,22 MutationAssessor,23 and MutationTaster24 predicted the pathogenicity of the HK1 p.Glu847Lys mutation. Jmol25 visualized the location of the HK1 mutation relative to known structural and enzymatic features and was used to generate three-dimensional (3D) structures. Multiple sequences were aligned with Clustal Omega.26 Retinal expression was assessed with the Human Retinal Transcriptome data browser.27

HK1 Gene and Mutation Nomenclature

Multiple HK1 isoforms of differing lengths have been reported. Mutation naming is based on HK1-I, NM_000188.2:c.2539G>A, NP_00179.2:p.Glu847Lys. Alternative names are NM_033496.2:c.2536G>A, NP_277031.1:p.Glu846Lys; NM_033497.2:c.2551G>A, NP_277032.1:p.Glu851Lys; NM_33498.2:c.2551G>A, NP_277033.1:p.Glu851Lys; NM_033500.2:c.2503G>A; and NP_277035.2:p.Glu835Lys.

Clinical Examinations

Comprehensive ophthalmic examinations included best-corrected visual acuity, static visual fields (Humphrey), kinetic visual fields (Goldmann), dark adaptometry, dark-adapted full-field ERG, spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) and autofluorescence (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany), binocular anterior and indirect ophthalmoscopy, and retinal imaging.

Results

Exclusion of Known adRP Genes in UTAD003

No mutations were found by Sanger sequencing of RHO, PRPF3, PRPF4, PRPF6, PRPF8, PRPF31, SNRNP200, PRPH2, ROM1, RP1, TOPORS, NRL, CRX, NR2E3, CA4, FSCN2, IMPDH1, KLHL7, RPE65, or SEMA4A in two affected members of UTAD003. No known or predicted likely-pathogenic mutations were found in a set of 46 retinal degeneration genes sequenced by NGS12 or in a separate screen of 163 retinal degeneration genes, also sequenced by NGS.12 Linkage testing of STR markers spanning all known adRP loci in the extended UTAD003 family excluded every locus tested. No likely-pathogenic mutations in known retinal degeneration genes were discovered during exome sequencing.15

Genome-Wide Linkage in UTAD003

Multipoint linkage analysis with only affected family members produced a single chromosomal region with a LOD score above 3.0, at chromosome 10q21.3-10q22.1. This region spans approximately 9 Mb and includes 96 putative genes, 87 of which are coding. After reconstruction of haplotypes through this region (Fig. 1), we observed that individual 16 was homozygous for all markers tested between D10S1652 and rs10998493. The region of apparent homozygosity overlaps but is smaller than the minimal critical region defined by recombinations in patients 11 and 12 (Fig. 1).

Identification of Variants by Exome Sequencing in UTAD003

Exome capture and NGS were done twice, first on a set of four affected individuals and later with another three affected patients plus an unaffected spouse. The entire exome dataset was analyzed, including data from outside the linkage region on chromosome 10. We identified 18,529 single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) that could be classified as rare: present in at least one affected individual but either absent from or with a minor allele frequency of less than 0.01 in dbSNP. Of these “rare” SNVs, only a single variant segregated with disease in the entire UTAD003 family: HK1 NM_000188.2:c.2539G>A, NP_000179.2:p.Glu847Lys.

The presence of this variant in all affected family members was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. No reports of this variant appear in any database (dbSNP,20 1000 Genomes,19 EVS28). As predicted from the linkage data, patient UTAD003-16 is homozygous for this variant.

Screening of HK1 in the adRP Cohort and Additional Families

The entire HK1 gene was screened by Sanger sequencing in the 59 other families of the UT adRP cohort (and UTAD003) that have previously tested negative for all of the currently known adRP genes.29 The entire gene was also sequenced in 25 additional adRP families. In all, 25 amplimers were tested in 85 unrelated probands, including all currently described coding and noncoding exons. Two families, UTAD936 and UTAD952 (Fig. 2), from the UT adRP cohort were found to carry the identical HK1 mutation. No other novel coding or splice-site changes were found in any of the samples tested. Based on the results from the UT cohort, the prevalence of this new mutation among autosomal dominant families is approximately 1% (3/265).

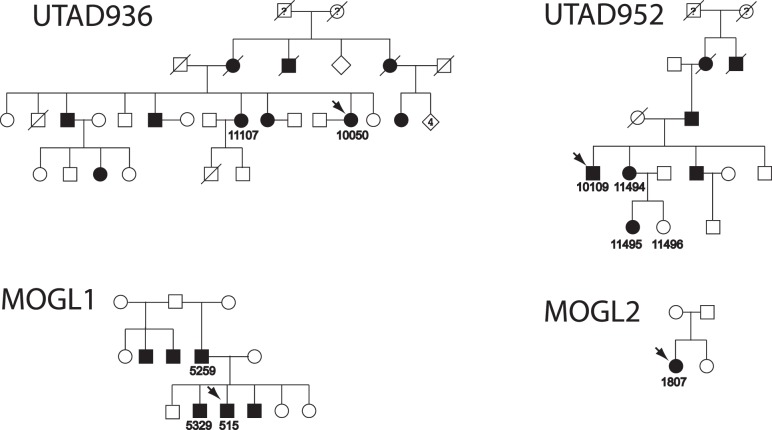

Figure 2.

Additional adRP families with the HK1 mutation. Filled symbols indicate diagnosis of adRP. Individuals for whom DNA samples are available are indicated with ID numbers; probands are shown with arrows.

An additional 403 affected probands from three collections of families with probable dominant retinal dystrophy (UT/RFSW, the National Ophthalmic Disease Genotyping and Phenotyping Network [eyeGENE], and the McGill Ocular Genetics Laboratory) were screened for mutations in the amplimer containing p.Glu847Lys only. In that set, two additional families (Fig. 2) with the identical HK1 p.Glu847Lys mutation were found, bringing the total to five. DNA samples from probands from each family with the p.Gly847Lys mutation were sequenced subsequently for the entire HK1 gene, but no additional variants were found.

Haplotype Analysis

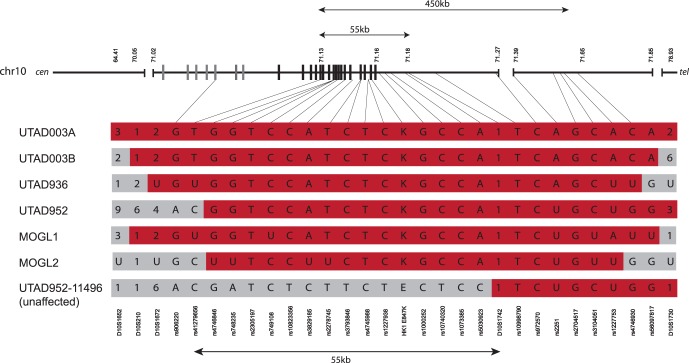

To determine if the five families are related, we examined the extended haplotype carrying the HK1 mutation (Fig. 3). All five families share a 450-kb region on chromosome 10 between markers rs4127956 and rs4746930. This region is also shared between the two HK1 mutation-carrying chromosomes in UTAD003-16.

Figure 3.

Reconstructed haplotypes flanking the HK1 mutation. Polymorphic STRs and SNVs flanking the mutation site were typed in all five adRP families. The haplotype in the UTAD003 family is reconstructed from patient 16, who is homozygous for this region of chromosome 10. UTAD003A is the HK1+ allele segregating with disease in the majority of the UTAD003 family; UTAD003B is the second allele inherited from patient 16′s father. SNP genotypes are indicated with letters (A, C, G, T) while STR genotypes are numerical. In cases in which the genotype segregating with disease could not be determined, a “U” is shown. Family haplotypes are shown in red where they are shared with the UTAD003 haplotype. The region shared by all six chromosomes containing the HK1 mutation is approximately 450 kb in length and lies between markers rs41279656 and rs4746930. UTAD952-11496 is an unaffected family member without the HK1 mutation who has an apparent recombination between rs5030923 and D10S1742, which limits the shared region to the 55 kb between markers rs41279656 and D10S1742. The schematic of chromosome 10 across the top shows the location of the HK1 gene, with untranslated exons as gray bars and translated exons as black bars.

Mutation Evaluation

Results from PolyPhen-2 analysis are inconclusive, as the results depend on the isoform analyzed. PolyPhen-2 utilizes sequence conservation and the proximity of the variant to known functional domains or structural features as its basis for predicting functional impact. The variant is predicted to be damaging in the longer retinal isoform (NP_277032) with a score of 0.99 and possibly damaging in the slightly shorter retinal isoform (NP_000179) with a score of 0.61. Mutation Taster, which utilizes additional information such as potential impact on splicing and sequence conservation at the nucleotide level, predicts the change to be disease causing (0.99). SIFT and Mutation Assessor, both of which rely heavily on sequence alignments and predicted sequence conservation, predict tolerated/low functional impact. The Grantham score for the mutation is 56, reflecting a relatively high level of biochemical similarity between glutamic acid and lysine, usually associated with tolerated variants.30

Clinical Details of Patients With the HK1 Mutation

UTAD003.

A review of medical records and recent clinical examination of several individuals indicated that the visual phenotype found in the UTAD003 family is highly variable (Table). Some individuals reported night blindness and/or patchy vision from early childhood while others did not have discernible symptoms well into their 50s or 60s. At least one individual could be described as asymptomatic at age 52, although mild retinal changes could be detected on examination. The age at RP diagnosis by an ophthalmologist ranged from the first to the sixth decade of life, with most affected members diagnosed during their 20s and 30s. Bone spicules, attenuated blood vessels, optic disc pallor, and peripheral atrophy were commonly seen during fundus examination. Many affected family members experienced a slow rate of vision loss and had a more pericentral pattern of degeneration and pigment deposition.

Table.

Clinical Characteristics of HK1 Mutation Families

|

Subject ID |

Geographic Origin |

Genotype |

Age of Onset |

Age at Exam |

Sex |

Visual Acuity |

Diagnosis |

| UTAD003-15 | Louisiana | HK1+/wt | Mid-30s | 68 | F | CF OD | CACD |

| 20/30 OS | |||||||

| UTAD003-13 | Louisiana | HK1+/wt | Late 20s | 56 | F | 20/25 OD | Pericentral RP |

| 20/20 OS | |||||||

| UTAD003-16 | Louisiana | HK1+/HK1+ | 4 | 34 | M | CF OD | RP, severe |

| 20/200 OS | |||||||

| UTAD003-21 | Louisiana | HK1+/wt | Unknown | 61 | F | 20/20 OD | Pericentral RP, mild |

| 20/20 OS | |||||||

| UTAD003-20 | Louisiana | HK1+/wt | NA | 52 | M | 20/20 OD | Asymptomatic |

| 20/20 OS | |||||||

| UTAD936-10050 | Louisiana | HK1+/wt | 24 | 56 | F | 20/32 OD | Pericentral RP |

| 20/80 OS | |||||||

| UTAD952-10109 | Louisiana | HK1+/wt | 13 | 51 | M | 20/40 OD | Pericentral RP |

| 20/50 OS | |||||||

| MOGL1-5259 | Quebec | HK1+/wt | 20 | 60 | M | CF OD | CACD |

| 20/60 OS | |||||||

| MOGL1-515 | Quebec | HK1+/wt | 25 | 45 | M | 20/20 OD | Pericentral RP |

| 20/20 OS | |||||||

| MOGL1-5231 | Quebec | HK1+/wt | 25 | 40 | M | 20/20 OD | Pericentral RP |

| 20/20 OS | |||||||

| MOGL2-1807 | Sicily | HK1+/wt | NA | NA | F | NA | adRP |

wt, wild type; CF, count fingers; OD, right eye; OS, left eye.

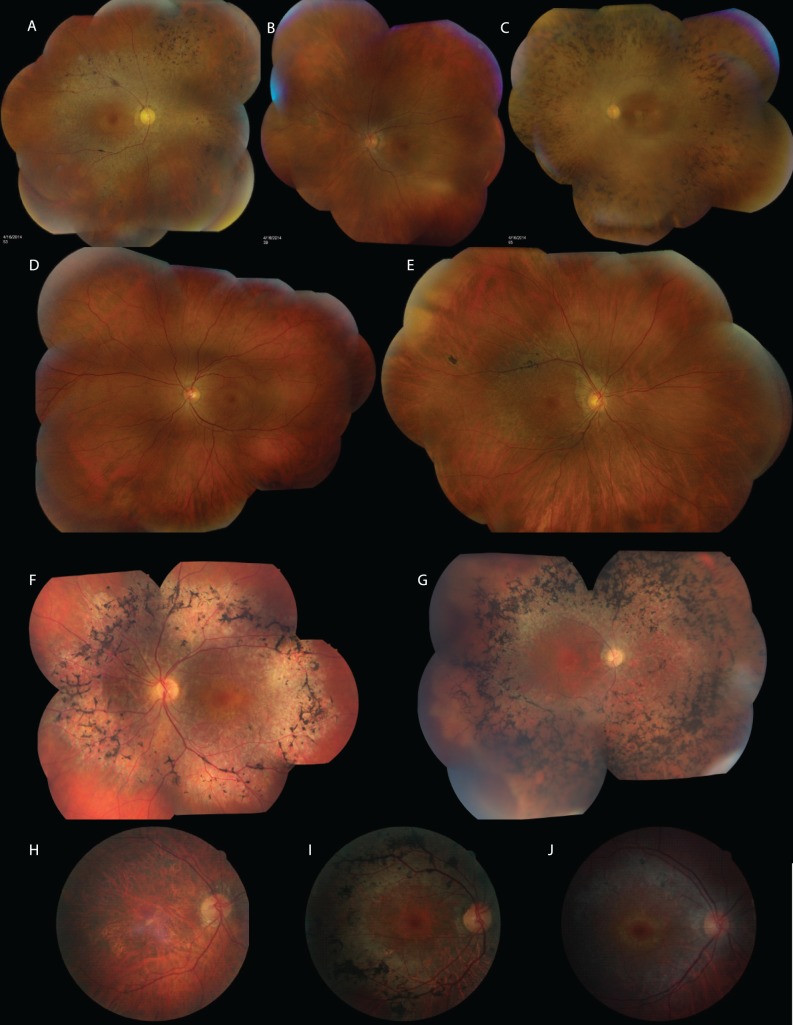

The most unusual member of the UTAD003 family is individual 16 (Fig. 4). This man provided a history of being suspect for RP at age 4 due to profound nyctalopia. When examined at age 33, his acuity was Count Fingers at 8 inches OD and 20/200 OS. Classic features of RP were evident in each eye: severe retinal vascular attenuation, diffuse optic disc pallor, extensive and broadly distributed pigment epithelial atrophy with bone spicule accumulation throughout the fundus, and macular atrophy in each eye consistent with the level of reduced acuity. Each parent carried a copy of the HK1 mutation, on slightly different haplotypes. His mother (UTAD003-13) was diagnosed with RP at age 30 and shows the pericentral pattern of atrophy and peripheral bone spicule deposition. His father was unavailable for ophthalmic examination; his clinical status is unknown.

Figure 4.

Clinical findings. (A) Montage of retinal images from subject UTAD003-15. Note the widespread RPE atrophy, vascular narrowing, and pigment migration. (B) Montage of retinal images from subject UTAD003-13. The retinal changes are similar to but less extensive than in UTAD003-15. (C) Montage of retinal images from subject UTAD003-16. This is the youngest person examined in this family; he is homozygous for the mutation. The visual function is far more advanced at a much younger age, and the retinal changes are far more severe than in other affected family members. (D) Montage of retinal images from subject UTAD003-21. Although this subject is only mildly symptomatic, the retinal changes are definitive of retinitis pigmentosa. (E) Montage of retinal images from subject UTAD003-20. In this man with no symptoms, the only evidence of disease is the gray ring around the fovea similar to that in his older siblings and mild vascular attenuation. (F) Montage of retinal images from subject UTAD936-10050. Heavy pigmentary deposits and focal areas of hypopigmentation are located primarily in the midperiphery. Retinal vessels are moderately attenuated. The far periphery appears relatively intact, consistent with the sizable full-field ERG and far peripheral sensitivity to the Goldmann V4e test target. (G) Montage of retinal images from patient UTAD952-10109. Dense midperipheral bone spicule pigmentation is interspersed with focal areas of hypopigmentation. Retinal vessels are severely attenuated. No vessels are visible nasal to the disc, for example. Abnormalities extend into the far periphery, consistent with the severely attenuated ERG and visual field sensitivity limited to the central retina. (H) Retinal image from MOGL1-5259 showing widespread macular atrophy, narrow vessels, lack of pigmentation, and a relatively normal-appearing optic disc. (I) Retinal image from MOGL1-515. This son's retinal appearance shows a bull's-eye maculopathy, with extensive RPE mottling and dense pigmentation around the arcades. (J) Retinal image from MOGL1-5321. This son also shows a bull's-eye maculopathy with RPE mottling around the arcades but lacks the pigmentary changes.

UTAD936.

UTAD936-10050, a 56-year-old female, was diagnosed with RP when she was 24 years old. In each eye, her central field was limited to 10° in all meridians, surrounded by extensive scotomas extending from 5° to 40°. Sensitivity peripheral to 40° was near normal. The patient retained sizable full-field ERG responses. In the left eye, rod responses were approximately 50% of normal amplitude, while cone responses were borderline normal in b-wave implicit time, only reduced by approximately 20% in amplitude. Retinal examination revealed vessel attenuation along with extensive peripheral bone spicule pigment in both eyes. Neither cystoid macular edema nor optic disc pallor occurred in either eye.

UTAD952.

Patient UTAD952-10109, a 51-year-old male, was diagnosed with RP as a young adult. Visual fields with spot size V (Humphrey) were reduced to 30° in all meridians in each eye with parafoveal scotomas. Full-field ERG rod responses were nondetectable. Cone responses to 30-Hz flicker were reduced in amplitude by 95% and significantly delayed in b-wave implicit time. Retinal examination revealed vessel attenuation with extensive peripheral bone spicule pigment in each eye. There was neither cystoid macular edema nor optic disc pallor in either eye.

MOGL1.

A 60-year-old male (5259) and two 40- and 45-year-old affected sons (5321 and 515) were seen at the McGill Ocular Genetics Clinic. There appear to be two distinct phenotypes in the family. While the father had central areolar choroidal dystrophy (CACD), the two sons had pericentral RP (Fig. 4). There was striking asymmetry in the eyes, and the OCT showed subretinal debris, with other material or crystals in the inner retina. We performed microscopy on the proband blood smear to study RBC morphology and found it to be normal. We tested the hypothesis that G6P levels would be reduced in the serum due to the HK1 mutation and found the levels to be normal.

MOGL2.

Patient 1807 is a 45-year-old Sicilian female with apparently unaffected parents and an unaffected sibling. No clinical details other than a diagnosis of RP are available.

Discussion

Multiple lines of evidence support the conclusion that the dominant p.Gly847Lys mutation in HK1 causes RP. The primary family, UTAD003, has been studied extensively for decades, and all previously identified RP genes have been excluded by various methods. The family is very large, with 10 meioses separating the most distantly related members, and linkage analyses produce a maximum LOD score of 6.2 at θ = 0 when the HK1 mutation is run as a marker at 10q22.1. Exome sequencing revealed only a single nonpolymorphic coding variant, HK1 p.Gly847Lys, that was found in all affected family members and has never been observed in normal controls. Although the phenotype is variable (in part with age) within the family, the individual homozygous for the mutation (UTAD003-16) has an age of onset and a clinical severity that are consistent with homozygosity for a dominant mutation.

In addition to the two HK1 mutation-carrying alleles in the UTAD003 family, we found four additional adRP families in which this novel mutation segregates completely with retinal disease phenotype in a dominant mode. Two of these families also have ties to Louisiana (but they cannot be connected by history or pedigree); one additional family is French Canadian, and the last is Italian. Analysis of the six chromosomal regions carrying the mutation allows us to reconstruct a common haplotype that extends from exon 16 of the HK1 gene to the middle of the COL13A1 gene, approximately 450 kb distal to HK1 (Fig. 3). This haplotype has not been observed in any HapMap31 populations tested, suggesting that it is rare in the population at large and is likely to have been the founder haplotype upon which the mutation first arose. Assuming population growth rates of 2.5%, 5%, and 10%, we estimate the age of the mutation (in generations) to range from 6 to 54, assuming that we have identified most of the families with this mutation, and 28 to 75 generations if we have identified a minority of families (15%).32

To rule out the possibility that the HK1 variant is benign but is in linkage disequilibrium with a pathogenic mutation in a nearby gene within the shared region, we examined the common haplotype in all five families. While every affected individual shared 450 kb of chromosome 10, the minimal region in which a mutation must be located is much smaller. A recombination event can be identified in an unaffected member of UTAD952 (who does not carry the HK1 mutation) that reduces the region to 55 kb, between rs41279656 and D10S1742. The only known gene in this smaller region is HK1, and all exons of HK1 were tested by Sanger sequencing in all five families. No nonpolymorphic variants were found, leaving the HK1 p.Glu847Lys mutation as the most likely cause of disease in this set of families.

Why Does the HK1 Mutation Cause Retinal Dystrophy?

The HK1 gene encodes the hexokinase 1 protein, best known as the enzyme that catalyzes the first step of glycolysis. Inside the photoreceptor, glucose is converted to G6P by hexokinase, effectively trapping it within the photoreceptor where it can be metabolized. In vertebrates, four genes encode hexokinases: HK1, HK2, HK3, and HK4 (also sometimes referred to as GCK), all derived from a common ancestor.33 HK1 is the most ubiquitous and is the predominant hexokinase in the brain, erythrocytes, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts. HK2 is expressed primarily in skeletal and cardiac muscle, adipose tissue, and rapidly growing tumors, while HK3 is expressed predominantly in white blood cells. HK4 is most prevalent in pancreas and liver.34

A proteomic study of rat retina35 investigating the localization of the glycolytic enzymes found that unlike most neurons, photoreceptors express both HK1 and HK2. In that study, HK1 was found throughout the retina, with strong expression in the photoreceptor inner segment as well as even higher concentrations in the outer plexiform layer, inner nuclear layer, inner plexiform layer, and ganglion cell layer. This contrasts to the location of HK2, which was found exclusively in photoreceptor inner segments. Although the distributions were quite different, overall expression levels were similar. This appears to be the case in human retina as well; transcriptome analyses of normal human retina show that the HK1 gene is expressed at about the same level as HK2, with HK3 and HK4 significantly lower.27

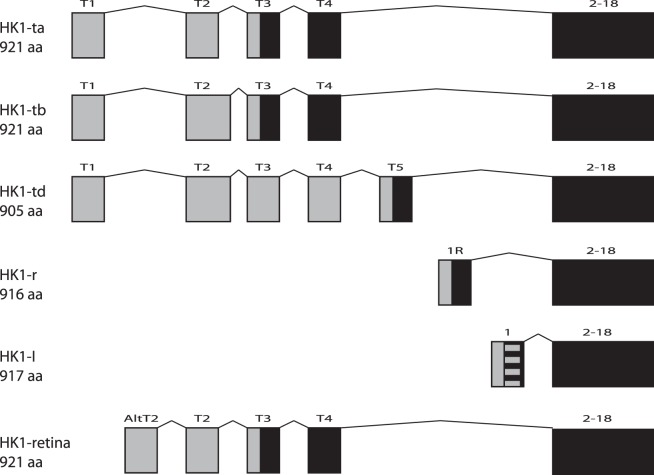

The HK1 gene has a number of alternative exons at its 5′ end (Fig. 5)36–39; these differing 5′ ends determine the subcellular localization of the isoforms. A total of five different protein isoforms have been described, ranging in size from 905 to 921 amino acids; all have the C-terminal 896 amino acids (17 exons) in common.39

Figure 5.

Isoforms of HK1. All known isoforms of HK1 share the same last 17 exons but differ at the 5′ end of the gene. Transcripts utilize different combinations of noncoding (gray) and coding (black) exons, producing proteins of differing lengths. Expression data (Human Retinal Transcriptome27) show that the transcripts indicated here as HK1-I (encoding NP_000179) and HK1 retina (encoding NP_277032) are the primary forms in human retina, expressed at approximately equal levels. The first exon of HK1-I contains the 12 amino acid porin-binding domain (PBD, striped box), which serves to localize this isoform to the mitochondrial outer membrane. The N-terminals of all the other isoforms, including HK1 retina, do not have this hydrophobic domain and do not localize to mitochondria.

Based on retinal expression data,27 two isoforms predominate in human retina. The most prevalent is HK1-I, an isoform of 917 amino acids, which has a single upstream exon in addition to the common 17 downstream exons (NP_000179). The 5′ exon of HK1-I encodes the hydrophobic porin-binding domain, which serves to localize this isoform to the outer mitochondrial membrane, via interaction with the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC1).37 The second isoform that appears to be highly expressed in retina was described by Hantke et al.39 It uses four of the alternative exons at its 5′ end, encoding a protein of 921 amino acids but without a porin-binding domain (NP_277032). This transcript is rare in other human tissues and appears in GenBank only as part of transcripts derived from the eye. All isoforms should contain the mutated codon, as it occurs in the penultimate exon.

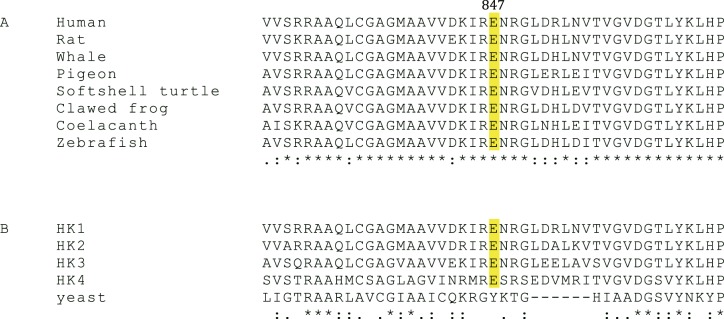

The p.Glu847Lys mutation occurs at a site that is highly conserved across HK1s from all vertebrates and is also highly conserved across the hexokinase gene family in general (Fig. 6). The glutamic acid at position 847 is 100% conserved in the 100+ vertebrate HK1 genes that have been sequenced.40 Comparing across all vertebrate hexokinases (HK1, HK2, HK3, HK4), 96% (377/393) have glutamic acid at this position. No vertebrate hexokinase sequence currently known has a lysine at this position (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Evolutionary conservation. (A) The glutamic acid at p.847 in HK1 is conserved in all vertebrates. (B) The equivalent position in human HK2, HK3, and HK4 is conserved across the gene family. Outside of vertebrates, conservation between hexokinases is limited to the active site. Sequence alignments performed with Clustal Omega.

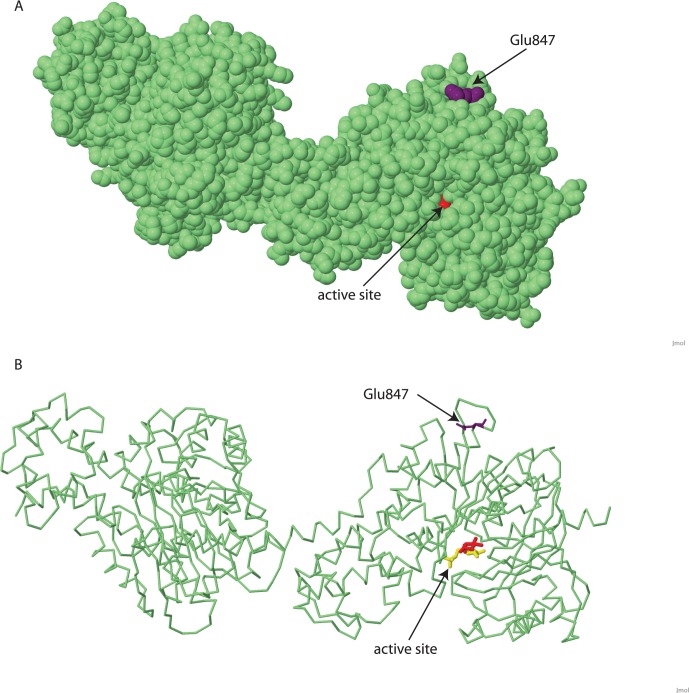

The p.Glu847Lys mutation is located in a region of the protein outside of all known functional domains. Models of HKI structure put the glutamic acid at position 847 on the surface of the protein, distant from the binding sites of glucose and G6P, as well as the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding sites (Fig. 7). In the extensive research done on modeling hexokinase 1 and its substrates and inhibitors, the region around amino acid 847 has not been implicated in any aspect of enzymatic function.41–46 A change at this amino acid from a glutamic acid to a lysine should not have severe structural consequences—the two amino acids are the same in approximate size, hydrophobicity, and hydrophilicity. The most substantial difference is that glutamic acid is negatively charged while lysine is positively charged.

Figure 7.

Location of p.Glu847 on known hexokinase 1 structure model. Model of recombinant human brain hexokinase type I complexed with glucose and glucose-6-phosphate. Amino acid 847 is shown in purple, glucose in red, and glucose-6-phosphate in yellow. (A) Location of glutamic acid 847 on the surface of the HK1 protein. The active site is located on the other side of the molecule, and the substrate binding pocket is only barely visible. (B) Wireframe view of same structure to visualize the active site and relative location of the mutation. Structures are modified from Protein Data Bank ID 1HKB, MMDB ID 4948143 using Jmol.25

In humans, low levels of hexokinase 1 caused by rare homozygous mutations impair glucose metabolism, resulting in early-onset nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia47 and the Russe form of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy,39 although the mechanism for the latter is unclear.48 These inherited anemias are extremely rare, with only 20 families reported to date (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 235700 and 605285).49 The causative mutations usually either affect the active site of the enzyme or reduce the expression of one or both alleles, leading to reduced hexokinase 1 activity in RBCs.49 Complete loss of both HK1 alleles is lethal and has been documented in one case with a homozygous deletion of four internal exons and death at a gestational age of 32 weeks.50

There is no evidence that carriers of the p.Glu847Lys mutation in HK1 have any phenotype other than a dominant-acting retinal degeneration. The hemolytic anemia found in recessive HK1 deficiency is not present, even in the homozygous patient. It is therefore unlikely that the mutation affects the normal enzymatic function of the protein or is causing any decrease in glucose metabolism. That does not imply that the mutation is not affecting an important HK1 function, but instead suggests that it may be a function that is exclusive to the retina. This would not be an unusual mechanism; for example, mutations in the IMPDH1 gene that also cause adRP do not affect the enzymatic activity of the protein. Instead, mutations in IMPDH1 disrupt a novel nucleic acid binding function that was discovered only after identification of pathogenic mutations.51–53

Additional functions for HK1 have come to light in recent studies, and it is possible that the mutation affects one of these. Numerous studies show that HK1 isoforms associated with mitochondria can interact with the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC1), located in the outer mitochondrial membrane, to inhibit apoptosis.54–57 When the interaction between VDAC1 and HK1 is altered by mutating VDAC1 or by VDAC1-based peptides, protection from apoptosis is decreased.54 Although HK1 and VDAC1 interact through the hydrophobic N-terminal domain of HK1, a mutation elsewhere in the protein could conceivably affect this interaction and increase apoptosis.

Additional proteins that interact with HK1 have been identified. The neuronal EF-hand protein, downstream regulatory element antagonist modulator (DREAM) interacts with HK1 in a CA2+-dependent manor and appears to regulate apoptosis.58 It is not yet known if DREAM displaces HK1 from VDAC1, or if another mechanism is involved. Another study has found substantial interactions between HK1, RanBP2, and Cox11 in the retina, suggesting that Cox11 binds to HK1 (at a site different from the active site) and inhibits catalysis. RanBP2 modulates this interaction59 and may serve as a chaperone for HK1.

Conclusions

We have identified a novel HK1 mutation as the cause of dominant retinal dystrophy in a large, six-generation family from Louisiana and in four additional families. This novel mutation is likely to be a founder mutation and, given the geographic origins of the five families, possibly predates European settlement of Canada and Louisiana. The phenotype of this form of adRP is variable, though a pattern of pericentral degeneration can be seen in multiple subjects (Table; Fig. 3). One individual who is homozygous for the mutation has the most severe retinal disease but has no other extraretinal or constitutional phenotype.

Although the hexokinases are best known for their indispensable role in glucose metabolism, other unrelated functions have been described recently.54–59 It is likely that the mechanism by which this mutation causes retinal degeneration, and only retinal degeneration, is a mechanism unique to the retina and unrelated to glycolysis. This would be similar conceptually to the way that IMPDH1 mutations cause adRP, without affecting the core enzymatic function of nucleotide synthesis. The location of the amino acid substitution in HK1 is far from any mapped functional site, and there is no indication that enzymatic activity is impaired. Thus the HK1 adRP mutation may act through a unique biological mechanism.

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without Mary Kay Pelias, PhD, JD, who worked closely with UTAD003 and many other families with inherited diseases in Louisiana throughout her career. We also thank these patients and their families for their willing and long-term participation and ongoing support. We thank Aimee Buhr for laboratory assistance. We thank the eyeGENE Network participants and National Eye Institute/National Institutes of Health staff for their valuable contributions to this research. Retinal images for family UTAD003 were provided by Dana Barnett.

Supported by Center and Individual grants, and a Wynn-Gund Translational Research Acceleration Program Award, from the Foundation Fighting Blindness; by National Institutes of Health Grant EY007142; and by Grant HG003079 from the National Human Genome Research Institute. SPD is Director of a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments Certified Laboratory in the National Ophthalmic Genotyping and Phenotyping (eyeGENE) Network of the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health. RAL is a Senior Scientific Investigator of Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, whose unrestricted funds supported part of this research. RKK is supported by the Canadian Foundation Fighting Blindness and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

Disclosure: L.S. Sullivan, None; D.C. Koboldt, None; S.J. Bowne, None; S. Lang, None; S.H. Blanton, None; E. Cadena, None; C.E. Avery, None; R.A. Lewis, None; K. Webb-Jones, None; D.H. Wheaton, None; D.G. Birch, None; R. Coussa, None; H. Ren, None; I. Lopez, None; C. Chakarova, None; R.K. Koenekoop, None; C.A. Garcia, None; R.S. Fulton, None; R.K. Wilson, None; G.M. Weinstock, None; S.P. Daiger, None

References

- 1. Heckenlively JR. Retinitis Pigmentosa. London: J.B. Lippincott; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Daiger SP. Identifying retinal disease genes: how far have we come, how far do we have to go? Novartis Found Symp. 2004; 255: 17–27, discussion 27–36, 177–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sullivan LS, Bowne SJ, Birch DG, et al. Prevalence of disease-causing mutations in families with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa: a screen of known genes in 200 families. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 3052–3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Churchill JD, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, et al. Mutations in the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa genes RPGR and RP2 found in 8.5% of families with a provisional diagnosis of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 1411–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Avery CE, et al. Mutations in the small nuclear riboprotein 200 kDa gene (SNRNP200) cause 1.6% of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis. 2013; 19: 2407–2417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Mortimer SE, et al. Spectrum and frequency of mutations in IMPDH1 associated with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa and Leber congenital amaurosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sullivan LS, Bowne SJ, Reeves MJ, et al. Prevalence of mutations in eyeGENE probands with a diagnosis of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 6255–6261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sullivan LS, Bowne SJ, Seaman CR, et al. Genomic rearrangements of the PRPF31 gene account for 2.5% of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 4579–4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gire AI, Sullivan LS, Bowne SJ, et al. The Gly56Arg mutation in NR2E3 accounts for 1-2% of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis. 2007; 13: 1970–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Gire AI, et al. Mutations in the TOPORS gene cause 1% of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis. 2008; 14: 922–927. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lathrop GM, Lalouel JM, Julier C, Ott J. Strategies for multilocus linkage analysis in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984; 81: 3443–3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Koboldt DC, et al. Identification of disease-causing mutations in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adRP) using next-generation DNA sequencing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 494–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang F, Wang H, Tuan HF, et al. Next generation sequencing-based molecular diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa: identification of a novel genotype-phenotype correlation and clinical refinements. Hum Genet. 2014; 133: 331–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daiger SP, Sullivan LS, Gire AI, Birch DG, Heckenlively JR, Bowne SJ. Mutations in known genes account for 58% of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adRP). Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008; 613: 203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koboldt DC, Larson DE, Sullivan LS, et al. Exome-based mapping and variant prioritization for inherited Mendelian disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2014; 94: 373–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O'Connell JR, Weeks DE. The VITESSE algorithm for rapid exact multilocus linkage analysis via genotype set-recoding and fuzzy inheritance. Nat Genet. 1995; 11: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bowne SJ, Humphries MM, Sullivan LS, et al. A dominant mutation in RPE65 identified by whole-exome sequencing causes retinitis pigmentosa with choroidal involvement. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011; 19: 1074–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). Exome Variant Server. Seattle, WA; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012; 491: 56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001; 29: 308–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003; 31: 3812–3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010; 7: 248–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reva B, Antipin Y, Sander C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: application to cancer genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39: e118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schwarz JM, Rodelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods. 2010; 7: 575–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jmol: an open-source Java viewer for chemical structures in 3D. 2014. Available at: http://www.jmol.org/. Accessed August 21, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011; 7: 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Farkas MH, Grant GR, White JA, Sousa ME, Consugar MB, Pierce EA. Transcriptome analyses of the human retina identify unprecedented transcript diversity and 3.5 Mb of novel transcribed sequence via significant alternative splicing and novel genes. BMC Genomics. 2013; 14: 486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tennessen JA, Bigham AW, O'Connor TD, et al. Evolution and functional impact of rare coding variation from deep sequencing of human exomes. Science. 2012; 337: 64–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Daiger SP, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, et al. Application of next-generation sequencing to identify genes and mutations causing autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adRP). Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014; 801: 123–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grantham R. Amino acid difference formula to help explain protein evolution. Science. 1974; 185: 862–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, et al. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010; 467: 52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reeve JPR, Rannala B. DMLE+: Bayesian linkage disequilibrium gene mapping. Bioinformatics. 2002; 18: 894–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Irwin DM, Tan H. Evolution of glucose utilization: glucokinase and glucokinase regulator protein. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2014; 70: 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Katzen HM, Schimke RT. Multiple forms of hexokinase in the rat: tissue distribution, age dependency, and properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1965; 54: 1218–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reidel B, Thompson JW, Farsiu S, Moseley MA, Skiba NP, Arshavsky VY. Proteomic profiling of a layered tissue reveals unique glycolytic specializations of photoreceptor cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110.002469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andreoni F, Ruzzo A, Magnani M. Structure of the 5′ region of the human hexokinase type I (HKI) gene and identification of an additional testis-specific HKI mRNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000; 1493: 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murakami K, Kanno H, Miwa S, Piomelli S. Human HKR isozyme: organization of the hexokinase I gene, the erythroid-specific promoter, and transcription initiation site. Mol Genet Metab. 1999; 67: 118–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wilson JE. Isozymes of mammalian hexokinase: structure, subcellular localization and metabolic function. J Exp Biol. 2003; 206: 2049–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hantke J, Chandler D, King R, et al. A mutation in an alternative untranslated exon of hexokinase 1 associated with hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy -- Russe (HMSNR). Eur J Hum Genet. 2009; 17: 1606–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002; 12: 996–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zeng C, Aleshin AE, Hardie JB, Harrison RW, Fromm HJ. ATP-binding site of human brain hexokinase as studied by molecular modeling and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1996; 35: 13157–13164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aleshin AE, Zeng C, Bartunik HD, Fromm HJ, Honzatko RB. Regulation of hexokinase I: crystal structure of recombinant human brain hexokinase complexed with glucose and phosphate. J Mol Biol. 1998; 282: 345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aleshin AE, Zeng C, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Fromm HJ, Honzatko RB. The mechanism of regulation of hexokinase: new insights from the crystal structure of recombinant human brain hexokinase complexed with glucose and glucose-6-phosphate. Structure. 1998; 6: 39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fang TY, Alechina O, Aleshin AE, Fromm HJ, Honzatko RB. Identification of a phosphate regulatory site and a low affinity binding site for glucose 6-phosphate in the N-terminal half of human brain hexokinase. J Biol Chem. 1998; 273: 19548–19553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aleshin AE, Kirby C, Liu X, et al. Crystal structures of mutant monomeric hexokinase I reveal multiple ADP binding sites and conformational changes relevant to allosteric regulation. J Mol Biol. 2000; 296: 1001–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rosano C, Sabini E, Rizzi M, et al. Binding of non-catalytic ATP to human hexokinase I highlights the structural components for enzyme-membrane association control. Structure. 1999; 7: 1427–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bianchi M, Magnani M. Hexokinase mutations that produce nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 1995; 21: 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sevilla T, Martínez-Rubio D, Márquez C, et al. Genetics of the Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in the Spanish Gypsy population: the hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy-Russe in depth. Clin Genet. 2013; 83: 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kanno H. Hexokinase: gene structure and mutations. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2000; 13: 83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kanno H, Murakami K, Hariyama Y, Ishikawa K, Miwa S, Fujii H. Homozygous intragenic deletion of type I hexokinase gene causes lethal hemolytic anemia of the affected fetus. Blood. 2002; 100: 1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Blanton SH, et al. Mutations in the inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase 1 gene (IMPDH1) cause the RP10 form of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Mol Genet. 2002; 11: 559–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mortimer SE, Xu D, McGrew D, et al. IMP dehydrogenase type 1 associates with polyribosomes translating rhodopsin mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283: 36354–36360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mortimer SE, Hedstrom L. Autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa mutations in inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase type I disrupt nucleic acid binding. Biochem J. 2005; 390: 41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Abu-Hamad S, Arbel N, Calo D, et al. The VDAC1 N-terminus is essential both for apoptosis and the protective effect of anti-apoptotic proteins. J Cell Sci. 2009; 122: 1906–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Azoulay-Zohar H, Israelson A, Abu-Hamad S, Shoshan-Barmatz V. In self-defence: hexokinase promotes voltage-dependent anion channel closure and prevents mitochondria-mediated apoptotic cell death. Biochem J. 2004; 377: 347–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Abu-Hamad S, Zaid H, Israelson A, Nahon E, Shoshan-Barmatz V. Hexokinase-I protection against apoptotic cell death is mediated via interaction with the voltage-dependent anion channel-1: mapping the site of binding. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283: 13482–13490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shoshan-Barmatz V, Zakar M, Rosenthal K, Abu-Hamad S. Key regions of VDAC1 functioning in apoptosis induction and regulation by hexokinase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009; 1787: 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Craig TA, Ramachandran PL, Bergen HR III, Podratz JL, Windebank AJ, Kumar R. The regulation of apoptosis by the downstream regulatory element antagonist modulator/potassium channel interacting protein 3 (DREAM/KChIP3) through interactions with hexokinase I. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013; 433: 508–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Aslanukov A, Bhowmick R, Guruju M, et al. RanBP2 modulates Cox11 and hexokinase I activities and haploinsufficiency of RanBP2 causes deficits in glucose metabolism. PLoS Genet. 2006; 2: e177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]