Abstract

Osteogenesis during bone modeling and remodeling is coupled with angiogenesis. A recent study shows that the specific vessel subtype, strongly positive for CD31 and Endomucin (CD31hiEmcnhi), couples angiogenesis and osteogenesis. We found that preosteoclasts secrete platelet derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB), inducing CD31hiEmcnhi vessels during bone modeling and remodeling. Mice with depletion of PDGF-BB in tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase positive (TRAP+) cell lineage (Pdgfb–/–) show significantly lower trabecular and cortical bone mass, serum and bone marrow PDGF-BB concentrations, and CD31hiEmcnhi vessels compared to wild-type mice. In the ovariectomized (OVX) osteoporotic mouse model, concentrations of serum and bone marrow PDGF-BB and CD31hiEmcnhi vessels are significantly decreased. Inhibition of cathepsin K (CTSK) increases preosteoclast numbers, resulting in higher levels of PDGF-BB to stimulate CD31hiEmcnhi vessels and bone formation in OVX mice. Thus, pharmacotherapies that increase PDGF-BB secretion from preosteoclasts offer a novel therapeutic target for osteoporosis to promote angiogenesis for bone formation.

INTRODUCTION

Bone size and shape is precisely modeled and remodeled throughout life to ensure the structure and integrity of the skeleton1,2. Primary factors in temporally and spatially regulating bone remodeling have been characterized3,4. Angiogenesis is coupled with bone formation in these processes5,6. A recent study reveals a specific vessel subtype, CD31hiEmcnhi vessel, couples angiogenesis and osteogenesis7,8. However, the cellular and molecular regulation of angiogenesis in coupling osteogenesis remains elusive.

During bone remodeling, osteoclast bone resorption is coupled with osteoblast bone formation by endocrine and paracrine factors to induce migration and differentiation of their respective precursors9,10. In response to stimulation with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), monocytes/macrophages first commit and become tartrate resistant acid phosphatase-positive (TRAP+) mononuclear cells (preosteoclasts)10. Preosteoclasts subsequently fuse to form TRAP+ multinuclear cells (osteoclast)10,11. Growth factors, such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and insulin-like growth factor type 1 (IGF-1) are released from the bone matrix during osteoclast bone resorption to induce migration and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) into osteoblasts for new bone formation12,13. During bone modeling, osteoclast bone resorption and osteoblast bone formation occur independently1. The cell signaling mechanisms that regulate bone modeling are less well understood, although humans and mice with osteopetrosis with impaired osteoclast function suggest osteoclasts may promote osteogenesis independent of resorptive activity14–17. There are abundant numbers of preosteoclasts on the periosteal bone surface, especially in regions associated with rapid growth18,19. Of note, v-ATPase V0 subunit D2-deficient mice with failure of fusion of preosteoclasts showed increased bone formation16. Recently, F4/80+ macrophages on periosteal and endosteal surfaces named OsteoMacs have also been shown to regulate in vitro mineralization of osteoblasts and are required for the maintenance of mature osteoblasts in vivo20,21.

An adequate blood supply is critical for bone health to transport nutrients, oxygen, minerals and metabolic wastes essential for osteoblastic bone matrix synthesis and mineralization22,23. Cortical bone is associated with a network of capillaries, which links periosteum and endosteum through a network of intracortical canals consisting of longitudinal Haversian canals and transversal Volkmann canals24,25. During modeling associated with growth, endothelial cells invade the cartilage at the growth plate region to form a vascular channel for nutrient supply and serve as a scaffold for new bone formation6,24. Capillaries are also present at bone remodeling sites and help further couple bone resorption and bone formation24,26. Angiogenesis involves migration and proliferation of endothelial cells, capillary tube formation, and MSC stabilization of newly formed tubes27,28. Of note, the interaction of MSCs with endothelial cells further regulates angiogenesis by secretion of angiogenic growth factors, cytokines, and other signaling molecules29,30. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) stimulates migration and angiogenesis of endothelia progenitor cells (EPCs) and MSCs31,32. PDGF-BB is believed to mobilize cells of mesenchymal origin, stabilize newly formed vessels and orchestrate cellular components for osteoblast differentiation33. It has been reported that osteoclasts secret PDGF-BB to induce migration of MSCs or osteoblasts34–36.

In this study, we report that preosteoclasts secrete PDGF-BB during bone modeling and remodeling to induce angiogenesis for osteogenesis. Depletion of PDGF-BB in the TRAP+ cell lineage reduces angiogenesis in the bone marrow and periosteum with reduced bone formation. Inhibition of cathepsin K (CTSK) effectively increases preosteoclasts and levels of PDGF-BB, stimulating CD31hiEmcnhi vessel and bone formation in ovariectomized (OVX) mice. Thus, PDGF-BB secreted by preosteoclasts stimulates angiogenesis further supporting osteogenesis.

RESULTS

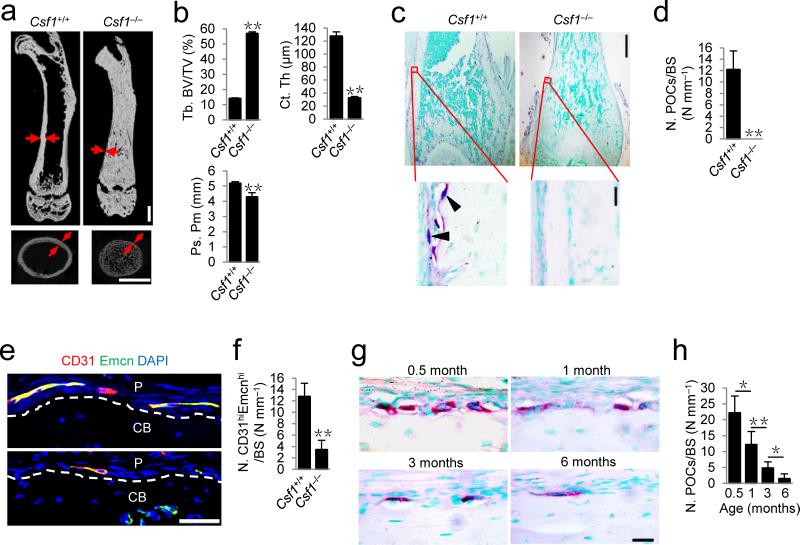

TRAP+ cell deficiency impairs cortical bone formation

To examine the role of osteoclast lineage cells in bone formation, we analyzed colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1)-deficient (Csf1–/–) mice, in which periosteal TRAP+ cells do not exist since CSF-1 is essential for survival of monocyte/macrophage lineage cells. Due to deficiency in osteoclast bone remodeling, a high volume of unmineralized bone37 was formed in Csf1–/– mice relative to their wild-type littermates (Fig. 1a,b). Notably, the cortical bones of Csf1–/– mice were extremely thin (Fig. 1a,b). The periosteal perimeter (Ps. Pm) of femoral diaphysis in the Csf1–/– mice was significantly lower relative to that of their wild-type littermates (Fig. 1b). TRAP staining of femur sections confirmed that there were no TRAP+ cells on the periosteal bone surface in the Csf1–/– mice (Fig. 1c,d). Co-immunostaining of CD31 and Endomucin (Emcn) demonstrated that the number of EmcnhiCD31hi vessels in the periosteum of Csf1–/– mice was significantly lower relative to that of their wild-type littermates (Fig. 1e,f).

Figure 1.

TRAP+ cell deficient mice exhibit reduced cortical bone. (a) μCT images of femora. Red arrows indicate cortical bone. Scale bars, 1 mm. (b) Quantitative μCT analysis of the trabecular bone fraction (Tb. BV/TV), cortical thickness (Ct. Th) and periosteal perimeter (Ps. Pm) of femora. n = 3. (c,d) TRAP staining images (c) and quantitative analyses of the number of preosteoclasts (N. POCs) on periosteal bone surface (BS) (d) of femoral diaphysis. Black arrowheads indicate preosteocasts. Scale bars, 500 μm (top), 20 μm (bottom). n = 5. (e,f) Confocal images of immunostaining of CD31 (red), Endomucin (green), and DAPI (blue) staining of nuclei (e), and quantitative analysis (f) of the number of cells notably positive for both CD31 and Endomucin (CD31hiEmcnhi, yellow) in femoral diaphyseal periosteum. Dashed lines outline the bone surface. P, periosteum; CB, cortical bone. Scale bar, 50 μm. n = 5. (g,h) TRAP staining images (g) and quantitative analysis of the number of preosteoclasts (N. POCs) on periosteal bone surface (h) of femoral diaphysis of the wild-type male mice at different ages. Scale bar, 20 μm. n = 5. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (b,d,f, t test; h, ANOVA).

Postnatal cortical bone grows quickly during puberty and the growth decreases gradually when approaching adulthood. We examined the numbers of preosteoclasts on the periosteal bone surface during postnatal growth through adulthood. The number of periosteal preosteoclasts was very abundant at day 15 after birth, decreased by 45% by 1 month of age, 78% by 3 months and was rarely detectable by 6 months (Fig. 1g,h). Consistent with previous reports18,19, periosteal TRAP+ cells were largely mononuclear (Fig. 1c,g). The observation suggests a potential role of preosteoclasts in cortical bone formation.

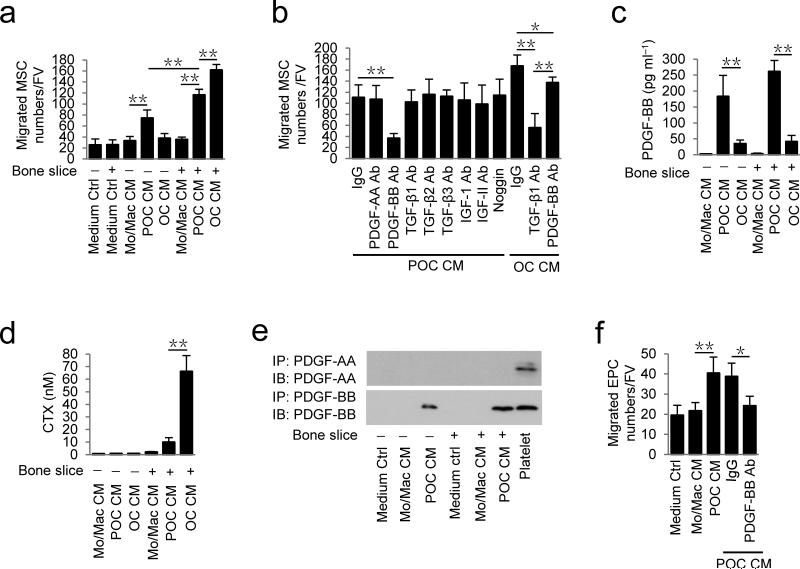

PDGF-BB from preosteoclasts induces MSC and EPC migration

To examine the potential molecular mechanism of preosteoclasts in regulation of trabecular bone remodeling and periosteal bone modeling, we cultured monocytes/macrophages to differentiate into preosteoclasts and osteoclasts, as evidenced with TRAP positive staining and the number of nuclei (Supplementary Fig.1a). We collected conditioned media of monocytes/macrophages, preosteoclasts and osteoclasts cultured with or without bone slices to identify the potential secreted factor (s). Conditioned medium of preosteoclasts induced significantly more MSC migration relative to control conditioned medium from monocytes/macrophages and the migration was further stimulated when a bone slice was added to the culture (Fig. 2a). Conditioned medium of osteoclasts without bone slice had very little effect on MSC migration, indicating that the unique factor(s) was secreted specifically in preosteoclast conditioned medium (Fig. 2a). To identify the secreted factor(s), we tested neutralizing antibodies against TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3, IGF-1, IGF-II, PDGF-AA and PDGF-BB, as well as noggin in the conditioned media. Only the antibody against PDGF-BB abolished the preosteoclast conditioned medium-induced migration (Fig. 2b). TGF-β1 neutralizing antibody inhibited the migration induced by the osteoclast bone resorption conditioned medium (Fig. 2b), consistent with our previous report12. ELISA analysis confirmed that preosteoclasts secreted PDGF-BB and bone slice enhanced the secretion, whereas osteoclasts with or without bone slice had significantly lower secretion of PDGF-BB versus preosteoclasts (Fig. 2c). Maturation of osteoclasts and their bone resorption activities were reflected by elevation of C-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen (CTX) concentrations in conditioned media (Fig. 2d). Western blot analysis of conditioned media confirmed PDGF-BB, not PDGF-AA (Fig. 2e).

Figure 2.

Preosteoclasts secrete PDGF-BB to induce migration of MSCs and EPCs. (a) Transwell assays for the migration of MSCs using conditioned medium (CM) collected from different cell cultures with (+) or without (−) bone slices. (b) Transwell assays for the migration of MSCs using conditioned medium of preosteoclasts + bone slices (POC CM) with addition of individual neutralizing antibody (Ab), IgG or Noggin, as indicated; or using conditioned medium of osteoclasts + bone slices (OC CM) with addition of individual neutralizing Ab or IgG. (c,d) ELISA analysis of concentrations of PDGF-BB (c) and CTX (d) in different conditioned media. (e) Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting analysis of PDGF-BB levels in different conditioned media. Platelet: mouse platelet lysate (positive control). (f) Transwell assays for the migration of EPC using conditioned media from different cell cultures as indicated or conditioned medium of preosteoclasts + bone slices (POC CM) with addition of IgG or PDGF-BB neutralizing Ab. FV: field of view (×200 magnification). Medium Ctrl: serum free α-MEM. Mo/Mac: monocytes/macrophages; POC: preosteoclasts; OC: osteoclasts. n = 4. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (ANOVA).

PDGF-BB is known to induce migration of EPCs and promote angiogenesis31. Indeed, conditioned medium from preosteoclasts also induced significantly more EPC migration than the control conditioned medium from monocytes/macrophages (Fig. 2f). The PDGF-BB neutralizing antibody abolished the preosteoclast conditioned medium-induced EPC migration (Fig. 2f). During osteoclastogenesis, preosteoclasts undergo fusion for osteoclast maturation and bone resorption. PDGF-BB secretion decreased gradually during fusion of preosteoclasts by ELISA assay (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Co-immunostaining of TRAP+ cells with PDGF-BB of cultured cells and mouse bone sections demonstrated that mature osteoclasts and monocytes/macrophages were largely PDGF-BB negative (Supplementary Fig. 1c,d). Thus, our results suggest that preosteoclasts prior to osteoclast maturation secrete PDGF-BB to recruit MSCs and EPCs. Our data suggest that osteoclast cultures with secretion of PDGF-BB as reported by other groups34-36 would contain preosteoclasts or premature osteoclasts. Furthermore, co-immunostaining demonstrated that TRAP+ preosteoclasts on both periosteal and endosteal bone surface are not F4/80+ OsteoMacs (Supplementary Fig. 2a), and F4/80+ OsteoMacs are PDGF-BB negative cells (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

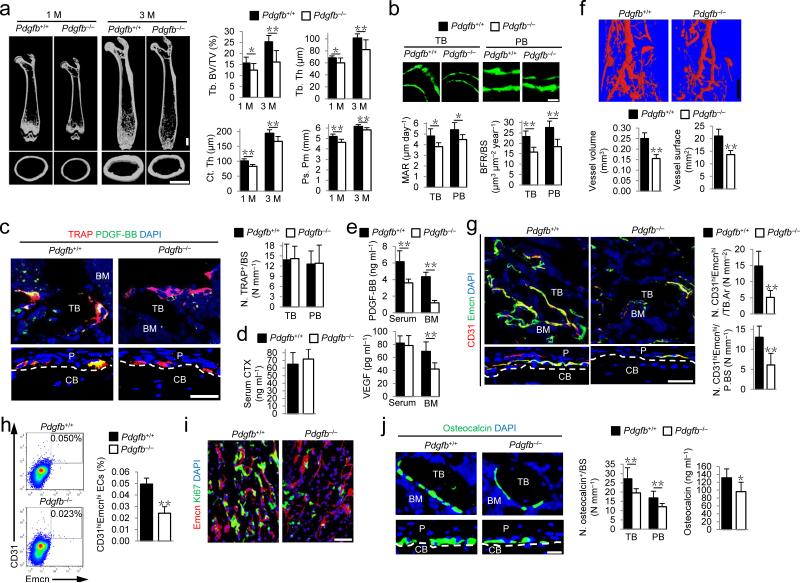

PDGF-BB from preosteoclasts induces bone formation in mice

We then examined the function of PDGF-BB secreted by preosteoclasts in bone remodeling and periosteal bone formation. Pdgfb floxed mice (Pdgfb+/+ mice) were crossed with TRAP-Cre mice to generate TRAP+ lineage-specific Pdgfb deletion mice (Pdgfb–/–). The trabecular bone volume, thickness, cortical bone thickness and periosteal perimeter were all lower in the Pdgfb–/– mice relative to their Pdgfb+/+ littermates (Fig. 3a). The reduction of trabecular bone mass and cortical bone formation was not associated with expression of TRAP-Cre transgene or Pdgfb flox allele alone (Supplementary Fig. 3). Calcein double labeling confirmed that Pdgfb–/– mice had lower bone formation in both trabecular and cortical bone versus their Pdgfb+/+ littermates (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Knockout of PDGF-BB in preosteoclasts reduces CD31hiEmcnhi vessels and bone formation. (a) μCT images and quantification of trabecular bone fraction (Tb. BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb. Th), cortical thickness (Ct. Th), and periosteal perimeter (Ps. Pm). Scale bars, 1 mm. (b) Calcein double labeling of trabecular (TB) and periosteal bone (PB) with quantification of mineral apposition rate (MAR) and bone formation rate (BFR). Scale bar, 20 μm. n = 5. (c) Immunostaining of TRAP (red) and PDGF-BB (green) with quantification of number of TRAP positive cells (N. TRAP+) per respective bone surface (BS). Scale bar, 50 μm. (d,e) ELISA for serum CTX (d), serum or bone marrow (BM) PDGF-BB and VEGF concentrations (e). (f) Microphil-perfused angiography with quantification of vessel volume and surface. Scale bar, 1 mm. n = 5. (g) Immunostaining of CD31 (red) and Endomucin (green) with quantification of CD31hiEmcnhi (yellow) cells in BM and periosteum (P) (bottom). Scale bar, 50 μm. (h) Flow cytometry plots (left) with percentage (right) of CD31hiEmcnhi cells in total bone marrow cells (BMCs). n = 4. (i) Immunostaining of Endomucin (red) and Ki67 (green). (j) Immunostaining of Osteocalcin (green) (left) with quantification of osteocalcin+ cell numbers (middle) on TB and PB surface. Serum osteocalcin concentrations by ELISA (right). Scale bar, 20 μm. Dashed lines outline bone surface. DAPI stains (blue) nuclei. CB, cortical bone; BM, bone marrow. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. n = 7−8, unless otherwise noted. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus Pdgfb+/+ (t test).

Co-immunostaining demonstrated that many TRAP+ cells were positive for PDGF-BB in both trabecular bone and periosteum of Pdgfb+/+ mice, but rarely observed in Pdgfb–/– mice (Fig. 3c). The number of TRAP+ cells and serum CTX concentrations were not changed in Pdgfb–/– mice relative to their Pdgfb+/+ littermates (Fig. 3c,d), indicating that specific deficiency of PDGF-BB in TRAP+ cells does not significantly affect osteoclast bone resorption. Of note, PDGF-BB concentrations in both bone marrow and peripheral blood were significantly lower and bone marrow vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) concentrations were also significantly lower in Pdgfb–/– mice than in their Pdgfb+/+ littermates (Fig. 3e). The bone marrow PDGF-BB concentration was lowered by 72.6% in Pdgfb–/– relative to their Pdgfb+/+ littermates (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Endothelial cells also express PDGF-BB38. We therefore further analyzed the relative contribution of PDFG-BB produced in the bone marrow by preosteoclasts and endothelial cells. We found that the PDGF-BB level in sorted endothelial cells (CD31+CD45−Ter119− cells) was about 46.0% of total bone marrow PDGF-BB protein in Pdgfb–/– mice (Supplementary Fig. 4b). The results estimate that bone marrow PDGF-BB is primarily from TRAP+ cells (72.6%), 12.6% from endothelial cells and 14.8% from the rest of the bone marrow cells (Supplementary Fig. 4c).

Microphil-perfused angiography showed that vessel volume and surface were significantly lower in Pdgfb–/– mice than in their Pdgfb+/+ littermates (Fig. 3f). Pdgfb–/– mice had significantly lower numbers of CD31hiEmcnhi endothelial cells in both marrow and periosteum versus their Pdgfb+/+ littermates (Fig. 3g,h). Pdgfb–/– mice had lower proliferation of endothelial cells in metaphysis versus their Pdgfb+/+ littermates (Fig. 3i). The lower osteocalcin+ osteoblastic cell numbers on trabecular and periosteal bone surface and lower serum osteocalcin concentration in Pdgfb–/– mice than in their Pdgfb+/+ littermates (Fig. 3j) further suggest that lower angiogenesis is related to less osteoblast bone formation. Taken together, PDGF-BB secreted by preosteoclasts stimulates angiogenesis and bone formation.

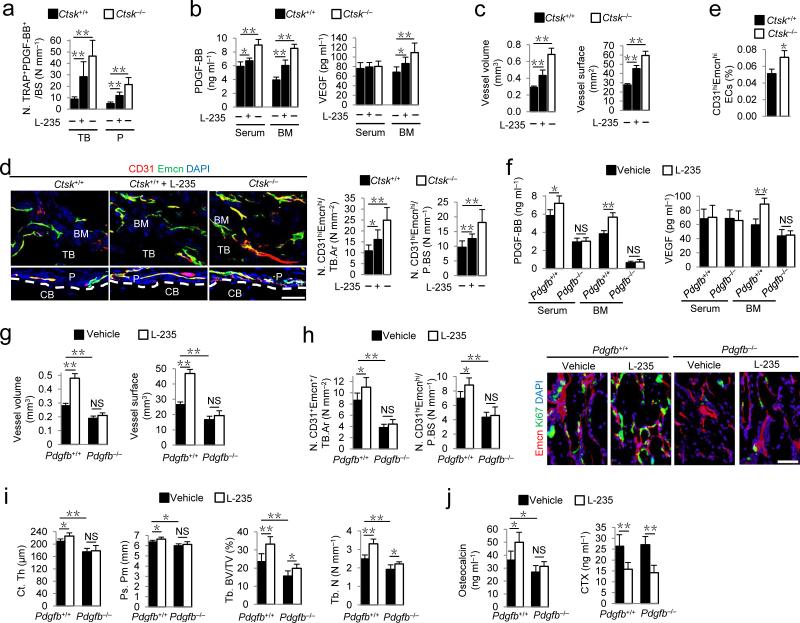

CTSK inhibition induces PDGF-BB secretion in preosteoclasts

Pycnodysostosis is a rare genetic osteopetrotic disease due to mutations in the Ctsk gene39. CTSK inhibition is under active investigation as a pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis. Preclinical and clinical data have noted impaired osteoclast bone resorption, but also increased numbers of preosteoclasts and osteoclasts and bone formation40–43. Preosteoclasts and osteoclasts from Ctsk–/– mice lack normal apoptosis and senescence and exhibit over-growth both in vitro and in vivo, which has been well characterized in a previous study40. We therefore examined whether CTSK inhibitor enhances secretion of PDGF-BB by preosteoclasts to promote angiogenesis and bone formation. We prepared conditioned media of preosteoclasts from Ctsk–/– mice and their wild-type littermates, and examined their effects on migration of MSCs and EPCs by the Transwell migration assay. The conditioned media from preosteoclasts with either inhibition of CTSK activity or gene deletion of Ctsk had higher concentrations of PDGF-BB protein (Supplementary Fig. 5a), and induced significantly more MSC and EPC migration versus conditioned medium from vehicle-treated wild-type preosteoclasts, and the elevated cell migration was abolished by a PDGF-BB neutralizing antibody (Supplementary Fig. 5b,c). Co-immunostaining of TRAP and PDGF-BB in longitudinal femur sections revealed that the number of TRAP+PDGF-BB+ cells was higher in the trabecular bone and periosteum in Ctsk–/– mice and wild-type mice treated with a CTSK inhibitor, L-006235 (L-235)44, than in vehicle-treated wild-type mice (Fig. 4a). PDGF-BB concentrations in both bone marrow and peripheral blood were significantly higher and bone marrow VEGF concentration was also higher (Fig. 4b), suggesting more angiogenesis. Vessel volume and surface in bone marrow, as well as CD31hiEmcnhi cells in both bone marrow and periosteum were significantly higher in Ctsk–/– mice and L-235-treated wild-type mice than in vehicle-treated wild-type mice (Fig. 4c–e). The trabecular bone volume and number, cortical bone thickness and periosteal perimeter, were all higher in Ctsk–/– mice and L-235-treated wild-type mice relative to vehicle-treated wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). Calcein double labeling confirmed that Ctsk–/– mice and L-235-treated wild-type mice had higher bone formation in both trabecular and cortical bone versus vehicle-treated wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 6c). The higher osteocalcin+ cell numbers and serum osteocalcin concentration in Ctsk–/– mice and L-235-treated wild-type mice than in vehicle-treated wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 6d,e) indicate more osteoblast bone formation.

Figure 4.

CTSK inhibitor increases TRAP+ cell PDGF-BB secretion to couple CD31hiEmcnhi vessels with bone formation. (a) Quantification of cells positive immunostaining for TRAP and PDGF-BB (N. TRAP+PDGF-BB+) on trabecular (TB) and periosteal (P) bone in wild-type (Ctsk+/+) with or without cathepsin K inhibitor (L-235) or knockout (Ctsk–/–) mice. n = 8. (b) PDGF-BB and VEGF concentrations by ELISA in serum and bone marrow (BM). n = 8. (c) Quantification of vessel volume and surface. n = 6. (d) CD31 (red) and Endomucin (green) immunostaining with quantification of CD31hiEmcnhi (yellow) cells. Scale bar, 50 μm. n = 8. (e) Percentage of CD31hiEmcnhi cells in total BM cells (BMCs) by flow cytometry. n = 3. (f) PDGF-BB and VEGF concentrations by ELISA in serum and BM of Pdgfb–/–or Pdgfb+/+ littermates treated with vehicle or L-235. n = 5. (g) Quantification of vessel volume and surface. n = 5. (h) Quantification of CD31hiEmcnhi immunostaining in TB (left) and P (middle). n = 5. Endomucin (red) and Ki67 (green) immunostaining of proliferating endothelial cells (right). (i) μCT quantification of cortical thickness (Ct. Th), periosteal perimeter (Ps. Pm), trabecular bone fraction (Tb. BV/TV) and trabecular thickness (Tb. Th). n = 5. (j) Serum osteocalcin and CTX concentrations by ELISA. n = 5. Dashed lines outline bone surface. DAPI stains (blue) nuclei. CB: cortical bone. Data shown as mean ± s.d. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, NS, not significant (ANOVA).

To validate that CTSK inhibitor-stimulated bone formation was mediated by increased angiogenesis and PDGF-BB secretion by preosteoclasts, we treated Pdgfb–/– mice with L-235. In Pdgfb–/– mice, the CTSK inhibition did not increase PDGF-BB and VEGF concentrations in either bone marrow or peripheral blood (Fig. 4f). As expected, CTSK inhibition did not increase vessel volume and surface, CD31hiEmcnhi cell numbers, and proliferation of metaphyseal endothelial cells in Pdgfb–/– mice (Fig. 4g,h). CTSK inhibition did not increase cortical bone thickness and periosteal perimeter (Fig. 4i) and only moderately increased trabecular bone volume and number in Pdgfb–/– mice (Fig. 4i). The inhibitor did not increase serum osteocalcin concentration in Pdgfb–/– mice while the bone resorption marker, CTX, in serum was lower in Pdgfb–/– mice and their wild-type littermates (Fig. 4j). These results reveal that inhibition of CTSK increases secretion of PDGF-BB to enhance angiogenesis for bone formation.

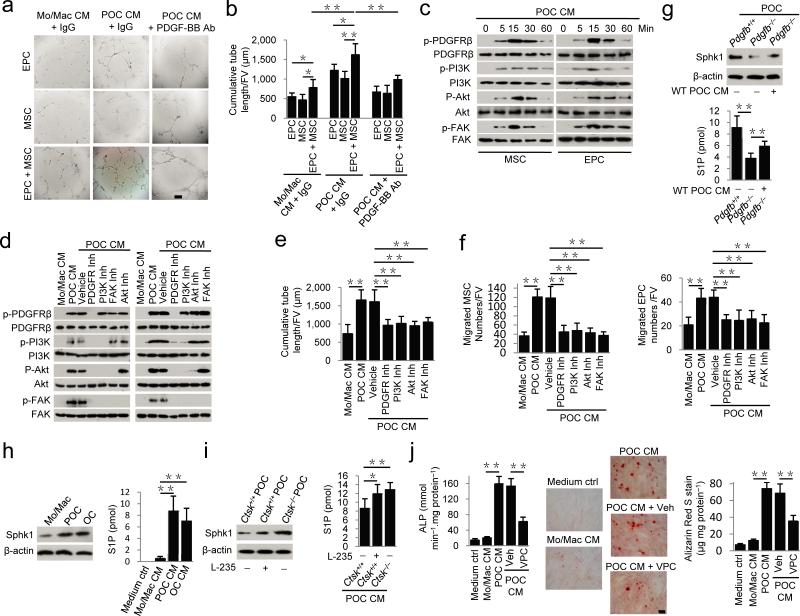

PDGF-BB from preosteoclasts induces angiogenesis via FAK

To examine the signaling mechanisms of PDGF-BB in promotion of angiogenesis coupled bone formation, we prepared conditioned media from preosteoclasts, monocytes/macrophage or control medium to culture EPCs, MSCs or both in co-culture. Preosteoclast conditioned medium induced EPC tube formation. Co-culture with MSCs significantly enhanced the EPC tube formation while addition of PDGF-BB neutralizing antibody attenuated the effect (Fig. 5a,b). Activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is known to mediate cell migration and angiogenesis45. Western blot analysis showed that preosteoclast conditioned medium induced phosphorylation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ) in both MSCs and EPCs by 5 min and peaked at 15 min (Fig. 5c). Phosphorylation of its downstream components phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), Akt and FAK also peaked at 15 min (Fig. 5c). Notably, the inhibitor for PDGFR blocked phosphorylation of PDGFR and the rest of the downstream kinases; the PI3K inhibitor blocked phosphorylation of PI3K, Akt and FAK; Akt inhibitor blocked phosphorylation of Akt and FAK, whereas FAK inhibitor only blocked phosphorylation of FAK (Fig. 5d). Independent inhibition of all components of this pathway were sufficient to block preosteoclast conditioned medium-induced tube formation of MSC and EPC co-culture, and migration of MSCs or EPCs (Fig. 5e,f). The results indicate that Akt-dependent activation of FAK signaling mediates PDGF-BB-induced cell migration and angiogenesis.

Figure 5.

Preosteoclast conditioned medium induces tube formation by MSCs and EPCs via Akt-dependent phosphorylation of FAK. (a,b) Matrigel tube formation assay images (a) and quantitative analysis of cumulative tube length (b) with MSC, EPC or both co-cultures using monocyte/macrophage (Mo/Mac) or preosteoclast (POC) conditioned medium (CM) with or without addition of neutralizing PDGF-BB antibody as indicated. Scale bar, 200 μm. (c,d) Western blot of the phosphorylation of PDGFRβ, PI3K, Akt and FAK in MSCs and EPCs treated with POC CM alone for 5−60 min (c), or plus respective inhibitors (d). (e) Quantitative analysis of POC CM-induced matrigel tube formation of MSC and EPC co-cultures pre-incubated with vehicle or respective inhibitors. (f) Transwell assays for POC CM-induced migration of MSCs (left) or EPCs (right) treated with vehicle or respective inhibitors. (g−i) Western blot of Sphk1 and β-actin (top) and mass spectrometry analysis of secreted S1P concentrations (bottom) in POC from Pdgfb+/+ or Pdgfb–/– mice with or without wild-type (WT) POC CM treatment (g), in different cells as indicated (h), or in POC from Pdgfb–/–or Pdgfb+/+ mice with or without cathepsin K inhibitor (L-235) treatment (i). (j) Alkaline phosphatase activity (left), Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining (middle), and ARS-based quantification of matrix mineralization (right) of MSCs were treated with CM as indicated in the presence or absence of an S1P receptor antagonist VPC23019 (VPC). Scale bar, 100 μm. OC: osteoclasts. n = 6. Data shown as mean ± s.d. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (ANOVA).

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), the product of phosphorylation of sphingosine by sphingosine kinase 1 (Sphk1), secreted by osteoclasts, stimulates osteoblast differentiation and function46,47. S1P and Sphk1 were increased during RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis46,47. Moreover, deletion of Ctsk increases Sphk1 expression and S1P production in osteoclasts48. S1P secretion and Sphk1 expression were lower in preosteoclasts of Pdgfb–/– mice than in preosteoclasts of age-matched Pdgfb+/+ mice (Fig. 5g), indicating S1P action is downstream of PDGF-BB. Indeed, Sphk1 expression and secreted S1P concentrations were significantly higher in preosteoclasts and osteoclasts than in monocytes/macrophages (Fig. 5h), consistent with the previous report46. Moreover, Sphk1 and S1P production were significantly higher in L-235-treated wild-type preosteoclasts or preosteoclasts from Ctsk–/– mice than in vehicle-treated wild-type preosteoclasts (Fig. 5i). Preosteoclast conditioned medium induced alkaline phosphatase activity and matrix mineralization of MSCs (Fig. 5j). The S1P1,3 antagonist VPC23019 reduced osteoblast differentiation (Fig. 5j). However, VPC23019 could not inhibit the preosteoclast conditioned medium-induced migration of MSCs or EPCs (Supplementary Fig. 5b,c). Altogether, PDGF-BB induces Akt/FAK-dependent angiogenesis in coupling osteogenesis by S1P signaling.

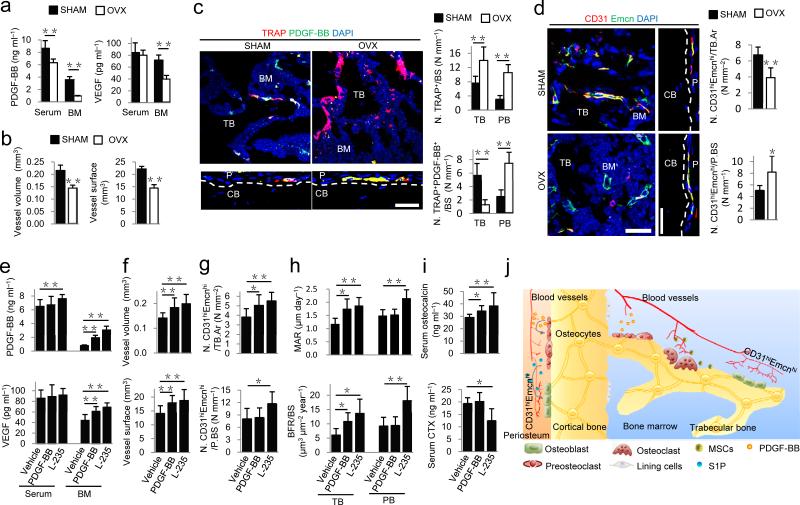

Increasing PDGF-BB attenuates bone loss in OVX mice

Postmenopausal osteoporosis is associated with increased osteoclastic bone resorption and decreased angiogenesis49–51. To examine the role of PDGF-BB in postmenopausal osteoporosis, we generated ovariectomized (OVX) mice, which had significantly lower uterus size and weight (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b), as well as significantly lower trabecular bone volume, thickness and number, and cortical thickness, compared to sham-operated (SHAM) mice (Supplementary Fig. 7c,d). PDGF-BB concentrations in both bone marrow and peripheral blood and the VEGF concentration in bone marrow were significantly lower in OVX mice than in SHAM mice (Fig. 6a). Microphil-perfused angiography demonstrated that vessel volume and surface were significantly lower in OVX mice than in SHAM mice (Fig. 6b). As expected, OVX mice had significantly higher numbers of osteoclasts versus SHAM mice (Fig. 6c). Of note, the osteoclasts were largely negative for PDGF-BB in the bone marrow of OVX mice while periosteal preosteoclasts were PDGF-BB-positive (Fig. 6c). Similarly, CD31hiEmcnhi cell numbers were significantly lower in marrow but higher in periosteum in OVX mice than in SHAM mice (Fig. 6d). Proliferation of endothelial cells in metaphysis was lower in OVX mice than in SHAM mice (Supplementary Fig. 7e).

Figure 6.

Increasing PDGF-BB stimulates CD31hiEmcnhi vessels and bone formation in OVX osteoporotic mice. (a) PDGF-BB and VEGF concentrations by ELISA in serum and bone marrow (BM) in sham-operated (SHAM) or ovariectomized mice (OVX). (b) Quantification of vessel volume and surface. (c) TRAP (red) and PDGF-BB (green) immunostaining and quantification of TRAP+ and TRAP+PDGF-BB+ cells on trabecular (TB) and periosteal bone (PB) surfaces, respectively. (d) CD31 (red) and Endomucin (green) immunostaining and quantification of CD31hiEmcnhi (yellow) cells in BM and periosteum. Scale bar, 50 μm. (e) PDGF-BB and VEGF concentrations by ELISA in serum and bone marrow of OVX mice treated with vehicle, PDGF-BB, or cathepsin K inhibitor (L-235). (f,g) Quantification of vessel volume and surface (f) and immunostaining of CD31hiEmcnhi cells (g). (h) Quantificaion of mineral apposition rate (MAR) and bone formation rate (BFR) in TB and periosteal bone (PB). (i) Serum osteocalcin and CTX concentrations by ELISA. (j) Model of PDGF-BB secreted by preosteoclasts to couple angiogenesis and osteogenesis. In periosteal bone modeling, preosteoclast secretion of PDGF-BB induces formation of CD31hiEmcnhi vessels and stimulates secretion of S1P to promote osteoblast differentiation. In trabecular bone remodeling, CD31hiEmcnhi vessels induced by preosteoclast secretion of PDGF-BB improves transport of nutrients, oxygen, minerals and metabolic wastes during bone remodeling. Dashed lines outline bone surface. Scale bar, 50 μm. Data shown as mean ± s.d. For a−d and h n = 5; For e−g and i n = 10. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (t-test and ANOVA).

We then examined whether increasing PDGF-BB could be an effective potential therapy for postmenopausal osteoporosis. We treated OVX mice with either local injection of PDGF-BB in the femur or systemic delivery of L-235. PDGF-BB concentrations were significantly increased in bone marrow of OVX mice with treatment of either PDGF-BB or L-235, but increased only in peripheral blood with treatment of L-235, compared to vehicle-treatment concentrations (Fig. 6e). Marrow VEGF concentrations were also increased in PDGF-BB or L-235 group compared to vehicle group (Fig. 6e). Microphil-perfused angiography demonstrated that OVX mice with treatment of either PDGF-BB or L-235 had significantly increased vessel volume and surface in bone marrow compared to vehicle-treatment levels (Fig. 6f). Bone marrow injection of PDGF-BB significantly increased CD31hiEmcnhi cells in bone marrow only, whereas L-235 significantly increased CD31hiEmcnhi cells in both marrow and periosteum compared to vehicle-treatment (Fig. 6g). Proliferation of endothelial cells in metaphysis was also increased in PDGF-BB and L-235 groups compared to vehicle group (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Treatment of OVX mice with either PDGF-BB or L-235 significantly increased trabecular bone volume, thickness and number relative to vehicle treatment (Supplementary Fig. 8b). The cortical bone thickness was increased and endosteal perimeter decreased significantly with administration of either PDGF-BB or L-235 (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Calcein double labeling confirmed increased trabecular bone formation with administration of either PDGF-BB or L-235 (Fig. 6h). Periosteal bone formation and periosteal perimeter were increased with L-235, but not with PDGF-BB, likely due to bone marrow local injection (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Fig. 8b). Serum osteocalcin concentrations were significantly increased with both treatments and CTX concentrations decreased with L-235 compared to vehicle treatment (Fig. 6i). Taken together, OVX osteoporotic mice demonstrate a decrease of PDGF-BB secretion and bone formation. Either local PDGF-BB administration or stimulation of preosteoclast secretion of PDGF-BB by systemic CTSK inhibition can temporally increase angiogenesis and spatially promote bone formation to couple angiogenesis with osteogenesis in bone modeling and remodeling.

DISCUSSION

Our study reveals that preosteoclasts secrete PDGF-BB to recruit EPCs and MSCs for angiogenesis in coupling with osteogenesis. Angiogenesis-induced by preosteoclasts is prepared for the oxygen, nutrients supply and metabolic waste transport of osteoclast bone resorption and coupled osteoblast bone formation during bone remodeling. Therefore, PDGF-BB secreted by preosteoclasts likely determines the temporal-spatial vessel formation for new bone formation (Fig. 6j). Vessel formation influences the microenvironment for differentiation of osteoprogenitors5,6. A recent study identifies a specific CD31hiEmcnhivessel subtype with distinct morphological, molecular properties and location. The abundance of the CD31hiEmcnhi vessels is associated with bone formation or bone loss7,8. We found that PDGF-BB secreted by preosteoclasts induces formation of the CD31hiEmcnhi vessel subtype in coupling bone formation. Notably, concentrations of PDGF-BB are significantly decreased in both bone marrow and peripheral blood in OVX osteoporotic mice and CD31hiEmcnhi vessels are also decreased in the bone marrow. Increase of mature bone resorption osteoclasts reduces preosteoclasts and their secretion of PDGF-BB in OVX mice, which likely affects bone formation. Knockout of Ctsk or injection of its inhibitor effectively increases the concentrations of PDGF-BB. Particularly, CTSK inhibitor increases angiogenesis including the subtype vessels and bone formation in OVX osteoporotic mice. Our finding of preosteoclast-induced angiogenesis represents a potential therapeutic target for bone loss, particularly for postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Cortical bone is a compact bone that provides mechanical support for the body weight and makes up 80 percent of the weight of the human skeleton2,52. In modeling, bone grows in both length and width, whereas in remodeling bone mass is maintained2,52. Longitudinal growth is achieved through endochondral ossification at the growth plate, as has been studied extensively53. However little is known about the mechanisms that regulate the width of bone, which is determined mainly by periosteal cortical bone formation. We found that periosteal preosteoclasts function as signaling cells by secreting PDGF-BB for periosteal bone formation. The periosteal TRAP+ cells expressing PDGF-BB are not F4/80+ OsteoMacs. Preosteoclasts have been observed previously in aquatic vertebrate skeleton54,55 and on the periosteal surface of cortical bone of mammals18,19. Preosteoclasts exhibit limited bone resorption but are oriented on the bone surface to direct osteogenesis.

PDGF-BB stimulates proliferation and migration of both EPCs and MSCs31,32. MSCs secrete angiogenic factors to induce angiogenesis of EPCs in vitro and in vivo29,30. Significant decrease of PDGF-BB in bone marrow and peripheral blood in the TRAP+ cell-specific PDGF-BB depletion mice indicates that preosteoclasts are the primary source for PDGF-BB. Both angiogenesis and bone formation are also decreased. The decrease of periosteal and marrow CD31hiEmcnhi cells demonstrates that PDGF-BB may regulate the coupling of angiogenesis with bone formation, suggesting that PDGF-BB secreted by preosteoclasts is key to both periosteal bone modeling and trabecular bone remodeling. The periosteum is a micro-vascularized connective tissue covering the outer surface of the cortical bone56, a special microenvironment that could resemble a unique marrow for cortical bone modeling and growth. PDGF-BB from TRAP+ preosteoclasts residing on the bone surface are able to temporally and spatially coordinate angiogenesis during bone growth, modeling and remodeling. Preosteoclast conditioned medium induces migration of MSCs and EPCs, and MSCs enhance tube formation in vitro assays. PDGF-BB from periosteal preosteoclasts stimulates secretion of S1P to also promote bone formation, further coupling angiogenesis in the periosteal environment. Modeling of trabecular bone could also be modulated by preosteoclasts via a similar mechanism, whereas in trabecular bone remodeling, two distinct factors are employed: TGF-β1 activation during bone remodeling recruits MSCs for bone formation12; PDGF-BB secreted by preosteoclasts prepares angiogenesis for anticipating bone formation in addition to recruitment of MSCs.

PDGF-BB has been widely used for bone regeneration and fracture healing57,58. PDGF-BB secreted by preosteoclasts to direct cortical bone formation provides the mechanism for its effectiveness in treatment of bone defects. CTSK is a cysteine proteinase and highly expressed in osteoclasts. It is responsible for bone matrix protein degradation during bone resorption59. The selective CTSK inhibitors decrease osteoclastic bone resorption activity by preventing the degradation of bone matrix proteins60. Deletion of Ctsk specifically in osteoclasts increases secretion of S1P for bone formation during bone remodeling48. The CTSK inhibitor has also been shown to increase cortical dimension in mice, monkeys and human and histomorphometrically demonstrated to stimulate periosteal bone formation of the long bones in preclinical models41–43. Notably, in Ctsk–/– mice and wild-type mice treated with a CTSK inhibitor, the number of periosteal preosteoclasts and the levels of PDGF-BB in the periosteum are significantly increased. Taken together the genetic and pharmacological findings demonstrate that stimulation of secretion of PDGF-BB by preosteoclasts may enhance the recruitment of EPCs and MSCs and are a potential therapeutic target for periosteal cortical defects and osteoporosis.

ONLINE METHODS

Mice generation

We purchased the Csf1op and Pdgfbfl/fl mouse strains from Jackson Laboratory. We obtained the TRAP-Cre mouse strain61 from Jolene J. Windle (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA). We obtained the Ctsk knockout (Ctsk–/–) mice62 from Bone Biology Group of Merck Research Laboratories. We generated Csf1–/– offspring and their wild-type littermates by crossing two heterozygote Csf1op strains. Hemizygous TRAP-Cre mice were crossed with Pdgfbfl/fl mice. The offspring were intercrossed to generate the following offspring: wild type mice, TRAP-Cre (mice expressing Cre recombinase driven by TRAP promoter), Pdgfbfl/fl (mice homozygous for Pdgfb flox allele are referred to as “Pdgfb+/+” in the text), and TRAP-Cre; Pdgfbfl/fl (mice with Pdgfb conditional deletion in TRAP lineage cells are referred to as “Pdgfb–/–” in the text).

We generated Ctsk–/– offspring and their wild-type littermates by crossing two heterozygote strains as described62. We analyzed male mice at 1 month of age, except as noted in specific experiments. We treated 4-week-old wild-type male mice, 6-week-old Pdgfb+/+ and Pdgfb–/– male mice daily with either vehicle or 50 mg kg−1 b.w. L-235 (Merck) for 30 d. L-235 was administered orogastrically in a 0.5% Methocel (w/v) suspension via a feeding tube.

We determined the genotype of the mice by PCR analyses of genomic DNA isolated from mouse tails using the following primers: Csf1OP allele forward, 5′-TGCTAACCTCGTGGTTCCTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTTAGCATTGGGGGTGTTGT-3′; TRAP-directed Cre forward, 5′-ATATCTCACGTACTGACGGTGGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTGTTTCACTATCCAGGTTACGG-3′; loxP Pdgfb allele forward, 5′-GGGTGGGACTTTGGTGTAGAGAAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGAACGGATTTTGGAGGTAGTGTC-3′; Ctsk forward, 5′-GCCACACCCACACCCTAGAAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-ACAAGTGTACATTCCCGTACC-3′.

For ovary removal surgery, 3-month-old C57BL/6 female mice were generally anesthetized and subjected to either a sham operation (SHAM) or bilateral ovariectomy (OVX). We randomly divided mice into five groups: SHAM, OVX, OVX + vehicle, OVX+ PDGF-BB, and OVX + L-235. For OVX + PDGF-BB group, recombinant mouse PDGF-BB (1 μg; Pepro Tech) was delivered into the bone marrow cavity of the OVX mice from the medial side of the patellar tendon using 0.5 ml-syringes with 27-gauge needles. The treatment was conducted once a month with the first injection at the same day of OVX. For OVX + L-235 group, L-235 (50 mg kg−1 b.w.) was delivered orogastrically into OVX mice. The treatment was conducted daily for 2 months. All mice were sacrificed at the age of 5-month-old. Whole blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture immediately after euthanasia, and serum samples obtained by centrifugation (1,500 rpm, 15 min) were stored at −80 °C prior to analyses. Uteri were isolated and weighed to confirm the effects of ovariectomy. Femora and tibia were also collected.

We maintained all animals in the Animal Facility of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

μCT analysis

Femora were dissected from mice free of soft tissue, fixed overnight in 70% ethanol and analyzed by high-resolution μCT (Skyscan 1172, Skyscan)13,63,64. The scanner was set at a voltage of 49 kVp, a current of 200 μA and a resolution of 8.7 μm per pixel. We used image reconstruction software (NRecon v1.6), data analysis software (CTAn v1.9) and three-dimensional model visualization software (μCTVol v2.0) in order to analyze the parameters of the diaphyseal cortical bone and the distal femoral metaphyseal trabecular bone. We established cross-sectional images of the femora to perform two-dimensional morphometric analyses of the cortical bone and three-dimensional histomorphometric analysis of the trabecular bone. Trabecular bone region of interest (ROI) was drawn starting from 5% of femoral length proximal to distal epiphyseal growth plate and extended proximally for a total of 5% of femoral length. The trabecular bone was segmented from the bone marrow and analyzed to determine the trabecular bone volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb. Th), trabecular number (Tb. N), and trabecular separation (Tb. Sp). Diaphyseal cortical bone ROI was drawn starting from 20% of femoral length proximal to distal epiphyseal growth plate and extended proximally for a total of 10% of femoral length. We analyzed the cortical bone in order to determine the cortical thickness (Ct. Th), periosteal perimeter (Ps. Pm), and endosteal perimeter (Es. Pm).

Angiography

We used μCT for imaging bone blood vessels as previously described65,66. Briefly, after euthanization of mice, the thoracic cavity was opened, a needle was inserted into the left ventricle, the vasculature was flushed with heparinized saline (0.9% normal saline containing 100 U ml−1 heparin sodium), 10% neutral buffered formalin was then injected for pressure fixation and then flushed from the vasculature using heparinized saline. A lead chromate-containing radiopaque silicone rubber compound (Microfil MV-122, Flow Tech.) was then injected into the vasculature. Mice were stored at 4 °C for 24 h and femora were then removed, fixed, decalcified and imaged by μCT. Vascular volume and surface were measured.

Immunocytochemistry, immunofluorescence and histomorphometry

For immunocytochemical staining, we incubated cultured cells with primary antibody to mouse PDGF-BB (Abcam, 1:50; Polyclonal) at 37 °C for 2 h, and subsequently used a horseradish peroxidase–streptavidin detection system (Dako) to detect the immunoreactivity, followed by TRAP staining using a staining kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

At the time of euthanasia, we dissected and fixed the femora with intact periosteum in 10% buffered formalin for 48 h, and decalcified them in 10% EDTA (pH 7.4) (Amresco) for 21 d and embedded them in paraffin or optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek). We processed four-micrometer-thick coronally (longitudinally) oriented sections of bone including the metaphysis and diaphysis for TRAP staining using a staining kit (Sigma-Aldrich). We performed immunofluorescence analysis of the bone sections as described previously13,64. Briefly, we incubated bone sections with individual primary antibodies to mouse CD31 (Abcam, 1:50, Polyclonal), endomucin (Santa Cruz, 1:50, V.7C7), TRAP (Santa Cruz, 1:200, Polyclonal), PDGF-BB (Abca, 1:50, Polyclonal), Ki67 (Novus Biologicals, 1:50, Polyclonal), osteocalcin (Takara, 1:200, Polyclonal) and F4/80 (Biolegend, 1:25, BM8) overnight at 4°. Subsequently, we used secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorescence at room temperature for 1 h while avoiding light. We used isotype-matched antibodies (R&D Systems) under the same conditions as negative controls. We counted the numbers of positively stained cells in the whole diaphyseal periosteum or four random visual fields of distal metaphysis per femur in five sequential sections per mouse in each group, and normalized them to the number per millimeter of adjacent bone surface (N mm−1) in trabecular and cortical bone or per square millimeter of bone marrow area (N mm−2) in trabecular bone. We used Leica TCS SP1 or SP2 confocal microscope or an Olympus BX51 Microscope for imaging samples.

To examine dynamic bone formation, we subcutaneously injected 0.1% calcein (Sigma, 10 mg kg−1 b.w.) in PBS into the mice 10 and 3 days before euthanization. We observed calcein double labeling in undecalcified bone slices under a fluorescence microscope. We measured periosteal bone formation at the site starting from 20% of femoral length proximal to distal epiphyseal growth plate and extended proximally for a total of 10% of femoral length. We measured trabecular bone formation in four randomly selected visual fields in distal metaphysis of femur.

Flow cytometry

For the analysis or sorting of CD31hiEmcnhi cells and total ECs in bone, after euthanization of 1-month-old male mice, we collected femora and tibiae, removed epiphysis at the end and the muscles and periosteum around the bone, and then crushed the metaphysis and diaphysis regions of the bone in ice-cold PBS. We digested whole bone marrow with collagenase at 37 °C for 20 min to obtain single cell suspensions. After filtration and washing, we counted cells and incubated equal numbers of cells for 45 min at 4 °C with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated endomucin antibody (Santa Cruz, V.7C7) for 45 min, then washed cells, and further incubated them with peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-conjugated CD31 antibody (Biolegend, 390) for 45 min at 4 °C. We also incubated cells for 45 min at 4 °C with phycoerythrin-, PerCP- and allophycocyanin-conjugated antibodies to mouse CD31 (Biolegend, 390), CD45 (Biolegend, 30-F11) and Ter119 (Biolegend, TER-119). We performed acquisition on a fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) Aria model (BD Biosciences), and did the analysis using FACS DIVE software version 6.1.3 (BD Biosciences). We sorted CD31+CD45−Ter119− cells as total bone marrow endothelial cells from total bone marrow cells. We collected sorted endothelial cells, as well as total bone marrow cells in an ELISA lysis buffer solution and stored them at −80 °C until ELISA analysis.

Isolation and culture of mouse bone marrow MSCs

After euthanization, we collected bone marrow cells from 6-week-old male wild-type mice and cultured them in alpha minimum essential medium (α-MEM, Mediatech, Inc.) containing 100 U ml−1 penicillin (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 20% lot-selected fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. After 72 h, we removed non-adherent cells and cultured adherent cells for an additional 7 d with a single media change. Then, we incubated cell aliquots for 20 min at 4 °C with fluorescein isothiocyanate-, phycoerythrin-, peridinin chlorophyll protein- and allophycocyanin-conjugated antibodies to mouse CD29 (Biolegend, HMβ1-1), Sca-1 (Biolegend, D7), CD45 (Biolegend, 30-F11) and CD11b (Biolegend, M1/70). We performed acquisition on a FACS Aria model (BD Biosciences), and did the analysis using FACS DIVE software version 6.1.3 (BD Biosciences). We sorted CD29+Sca-1+CD45−CD11b− cells and enriched them by further culture.

Preparation of conditioned media from preosteoclasts and osteoclasts

We prepared different types of conditioned media from preosteoclasts or osteoclasts. We harvested monocytes/macrophages from bone marrow of 6-week-old wild-type male mice by flushing the marrow space of femora and tibiae. We cultured the flushed bone marrow cells overnight on Petri dishes in α-MEM containing 10% FBS, 100 U ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin sulfate and 30 ng ml−1 M-CSF (R&D Systems Inc.). After discarding the adherent cells, we incubated floating cells with M-CSF (30 ng ml−1) in order to obtain pure monocytes/macrophages. Upon incubation of monocytes/macrophages with or without bovine cortical bone slices in 24-well plates (1 × 105 cells per well) with 30 ng ml−1 M-CSF and 60 ng ml−1 RANKL (PeproTech), all cells became preosteoclasts after a 3 d culture. Alternatively, fully mature multinucleated osteoclasts were formed after incubation with 30 ng ml−1 M-CSF and 200 ng ml−1 RANKL for 8 d. We detected TRAP activities of the cultured preosteoclasts and mature osteoclasts using a commercial kit (Sigma-Aldrich). At the end of induction, we harvested serum-containing conditioned medium from the preosteoclasts and mature osteoclasts. Serum-free conditioned media were also harvested after one more day culture with serum-free medium containing the same concentrations of M-CSF and RANKL. After a centrifugation (2,500 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C), we aliquoted conditioned media and stored them at –80 °C. We used serum-free conditioned media for migration experiments and serum-containing conditioned media for osteogenic differentiation induction experiments. In some experiments, we added the neutralizing antibodies for certain factors including PDGF-AA (R&D, 1 μg ml−1, Polyclonal), PDGF-BB (Abcam, 1 μg ml−1, Polyclonal), TGF-β1 (R&D, 2 μg ml−1, 9016), TGF-β2 (R&D, 2 μg ml−1, Polyclonal), TGF-β3 (R&D, 1 μg ml−1, 20724), IGF-1 (R&D, 2 μg ml−1, Polyclonal), IGF-II (R&D, 1 μg ml−1, Polyclonal), IgG (R&D), as well as Noggin (100 ng ml−1; BD Biosciences) to the conditioned media.

In vitro assays for migration of MSCs and EPCs

We assessed cell migration in Transwell-96 well plates (Corning Inc.) with 8 μm pore filters. Briefly, we seeded 1 ×104/well MSCs or EPCs in the upper chambers and preincubated them with either vehicle, 20 μM AG1296 (a PDGFR inhibitor; Cayman Chemical), 30 μM LY294002 (a PI3K inhibitor; Cayman Chemical), 10 μM MK2206 (a Akt inhibitor; Sellechchem), or 2 μM Y15 (a FAK inhibitor; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h, then incubated them with conditioned medium from the presoteoclasts or BMCM in the lower chambers for further 4 h, with the inhibitor or vehicle remained in the upper chambers. At the end of incubation, we fixed the cells with 10% formaldehyde for 30 min, and then removed the cells on the upper surface of each filter with cotton swabs. We stained the cells that had migrated through the pores to the lower surface with crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) and quantified them by counting five random fields per well using a microscope (Olympus) at ×200 magnification.

Bone marrow supernatant collection

We exposed bone marrow of euthanized mice after cutting two ends of tibia and placed the samples for centrifugation for 15 min at 3,000 rpm and 4 °C to obtain bone marrow supernatants, which we then stored at −80 °C until ELISA assay.

ELISA analysis

We performed osteocalcin or CTX ELISA analysis of serum using a mouse osteocalcin EIA kit (Biomedical Technologies Inc.) or a RatLapsTM EIA kit (Immunodiagnosticsystems). We performed CTX ELISA analysis of conditioned media using a CrossLaps® for Culture ELISA kit (Immunodiagnosticsystems). We performed PDGF-BB or VEGF ELISA analysis of conditioned medium, serum or bone marrow supernatant using a Mouse/Rat PDGF-BB Quantikine ELISA kit or a Mouse VEGF Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems). We did all ELISA assays according to the manufacturers' instructions.

In vitro assays for tube formation by EPCs, MSCs or co-culture

We plated Matrigel (BD Biosciences) in 96-well culture plates and incubated at 37 °C to polymerise for 45 min. We then seeded EPCs (2 × 104 cells/well), MSCs (2 × 104 cells/well), or combined MSCs (1 × 104 cells/well) and EPCs (1 × 104 cells/well) on polymerized Matrigel in plates. We cultured the cells with conditioned medium collected from preosteoclasts or monocytes/macrophages culture system. After incubation at 37 °C for 4 h, we observed tube formation by microscopy, and measured the cumulative tube lengths. In some experiments, we added the neutralizing antibody for PDGF-BB described above to preosteoclast conditioned medium. In another set of experiments, we preincubated the cells with AG1296 (20 μM), LY294002 (30 μM), MK2206 (10 μM) or Y15 (2 μM), specific inhibitors for PDGFR, PI3K, Akt or FAK, respectively, for 1 h, before incubating them with the conditioned media.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

We measured PDGF-BB concentrations in conditioned media by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting analysis as described67. Briefly, for immunoprecipitation, we incubated conditioned media with PDGF-AA or PDGF-BB antibodies described above and then used Protein G-Sepharose to absorb antigen-antibody complexes (Amersham Biosciences).

We separated immunoprecipitates or total cell lysates by SDS-PAGE and then blotted them on a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). We incubated the membranes with specific antibodies to PDGF-AA (1:2000), PDGF-BB (1:1000), p-PDGFRβ (Abcam, 1:2000, polyclonal), PDGFRβ (Santa Cruz, 1:1000, polyclonal), p-PI3K (Cell Signaling, 1:1000, polyclonal), PI3K (Cell Signaling, 1:1000, polyclonal), p-Akt (Cell Signalig, 1:1000, 193H12), Akt (Cell Signalig, 1:2000, 40D4), p-FAK (Santa Cruz, 1:500, Polyclonal), FAK (Santa Cruz, 1:500, Polyclonal), Sphk1 (Abcam, 1:500, Polyclonal) or β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, 1:10000, AC-15), and then developed the blots by an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Biosciences).

Measurement of S1P in conditioned medium

We processed conditioned media prepared as described above for mass spectrometry. We extracted S1P as previously described48. Briefly, we added 100 μl 3N NaOH into the medium (1 ml) with addition of C17-S1P (100 pmol; internal standard) for alkalization, then mixed with 1 ml CHCl3, 1 ml CH3OH, and 9 μl HCl. We centrifuged the mixture at 300 g for 5 min to separate the alkaline aqueous phase containing S1P. We re-extracted the organic phase with 0.5 ml methanol, 0.5ml 1N NaCl and 50 μl 3N NaOH. We acidified the collected aqueous phases with 100 μl concentrated HCl, and extracted the dephosphorylated sphingosine extracted twice with 1.5 ml CHCl3 each. We then dried the combined CHCl3 phases under vacuum and resuspended them in 200 μl CH3OH. We performed sample analysis using Voyager DE-STR mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems).

Assessment of osteogenic differentiation of MSCs

We seeded MSCs at a density of 5 × 103 cm−2 with serum-containing conditioned media from preosteoclast cultures. Serum-containing conditioned medium from monocyte/macrophage cultures served as a control. After 2 d of culture, we homogenized the cells, and assayed ALP activity by spectrophotometric measurement of p-nitrophenol release using an enzymatic colorimetric ALP Kit (Roche). After 3 weeks of culture, we evaluated the cell matrix mineralization by Alizarin Red S staining (2% of Alizarin Red S [Sigma-Aldrich] dissolved in distilled water with the pH adjusted to 4.2). Alizarin Red S staining was released by cetyl-pyridinium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) and quantified by spectrophotometry. To normalize protein expression to total cellular protein, an aliquot of the cell lysates was measured with the Bradford protein assay.

Statistical analysis

All error bars are s.d. Data presented as mean ± s.d. We used unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-tests for comparisons between 2 groups, and One Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons. All data demonstrated a normal distribution and similar variation between groups. For all experiments, P < 0.05 were considered to be significant and indicated by '*'; P < 0.01 were indicated by '**'. All inclusion/exclusion criteria were preestablished and no samples or animals were excluded from the analysis. No statistical method was used to predetermine the sample size. The experiments were randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by US National Institutes of Health grants DK 057501 and AR 063943 (to X.C.); and China National Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists grant 81125006 (to X.L.).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.X. conceived the ideas for experimental designs, conducted the majority of the experiments, analyzed data and prepared the manuscript. Z.C., L.W., Z.X. and Y.H. maintained mice and collected tissue samples, performed μCT analyses, conducted immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence, conducted cell culture and Western blot, and helped with manuscript preparation. L.X., C.L. L.X. and W.C. maintained mice and helped with Flow cytometry, cell culture and Transwell migration assay. J.C., M.W., G.Z., Q.B., B.Y. and M.P. provided suggestions for the project and critically reviewed the manuscript. T.Q. performed confocal imaging. L.T.D. and J.J.W. provided mouse models. X.L. and E.L. participated in experimental design and helped compose the manuscript. X.C. developed the concept, supervised the project, conceived the experiments and wrote most of the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

Supplementary Information includes 8 figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seeman E. Bone modeling and remodeling. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2009;19:219–233. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v19.i3.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teti A. Bone development: overview of bone cells and signaling. Current osteoporosis reports. 2011;9:264–273. doi: 10.1007/s11914-011-0078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eriksen EF. Cellular mechanisms of bone remodeling. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2010;11:219–227. doi: 10.1007/s11154-010-9153-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaidi M. Skeletal remodeling in health and disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:791–801. doi: 10.1038/nm1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Portal-Nunez S, Lozano D, Esbrit P. Role of angiogenesis on bone formation. Histol Histopathol. 2012;27:559–566. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandi ML, Collin-Osdoby P. Vascular biology and the skeleton. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:183–192. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusumbe AP, Ramasamy SK, Adams RH. Coupling of angiogenesis and osteogenesis by a specific vessel subtype in bone. Nature. 2014;507:323–328. doi: 10.1038/nature13145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramasamy SK, Kusumbe AP, Wang L, Adams RH. Endothelial Notch activity promotes angiogenesis and osteogenesis in bone. Nature. 2014;507:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature13146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sims NA, Martin TJ. Coupling the activities of bone formation and resorption: a multitude of signals within the basic multicellular unit. BoneKEy reports. 2014;3:481. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2013.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del Fattore A, Teti A, Rucci N. Bone cells and the mechanisms of bone remodelling. Frontiers in bioscience (Elite edition) 2011;4:2302–2321. doi: 10.2741/543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishii M, Saeki Y. Osteoclast cell fusion: mechanisms and molecules. Modern rheumatology / the Japan Rheumatism Association. 2008;18:220–227. doi: 10.1007/s10165-008-0051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang Y, et al. TGF-beta1-induced migration of bone mesenchymal stem cells couples bone resorption with formation. Nat Med. 2009;15:757–765. doi: 10.1038/nm.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xian L, et al. Matrix IGF-1 maintains bone mass by activation of mTOR in mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 2012;18:1095–1101. doi: 10.1038/nm.2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henriksen K, Karsdal MA, Martin TJ. Osteoclast-derived coupling factors in bone remodeling. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014;94:88–97. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9741-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Fattore A, et al. Clinical, genetic, and cellular analysis of 49 osteopetrotic patients: implications for diagnosis and treatment. J Med Genet. 2006;43:315–325. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.036673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SH, et al. v-ATPase V0 subunit d2-deficient mice exhibit impaired osteoclast fusion and increased bone formation. Nat Med. 2006;12:1403–1409. doi: 10.1038/nm1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henriksen K, et al. A specific subtype of osteoclasts secretes factors inducing nodule formation by osteoblasts. Bone. 2012;51:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baroukh B, Cherruau M, Dobigny C, Guez D, Saffar JL. Osteoclasts differentiate from resident precursors in an in vivo model of synchronized resorption: a temporal and spatial study in rats. Bone. 2000;27:627–634. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ochareon P, Herring SW. Cell replication in craniofacial periosteum: appositional vs. resorptive sites. J Anat. 2011;218:285–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang MK, et al. Osteal tissue macrophages are intercalated throughout human and mouse bone lining tissues and regulate osteoblast function in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:1232–1244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander KA, et al. Osteal macrophages promote in vivo intramembranous bone healing in a mouse tibial injury model. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1517–1532. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi IH, Chung CY, Cho TJ, Yoo WJ. Angiogenesis and mineralization during distraction osteogenesis. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:435–447. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.4.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Percival CJ, Richtsmeier JT. Angiogenesis and intramembranous osteogenesis. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2013;242:909–922. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chim SM, et al. Angiogenic factors in bone local environment. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24:297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pazzaglia UE, et al. Morphometric analysis of the canal system of cortical bone: An experimental study in the rabbit femur carried out with standard histology and micro-CT. Anat Histol Embryol. 2010;39:17–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.2009.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parfitt AM. The mechanism of coupling: a role for the vasculature. Bone. 2000;26:319–323. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(00)80937-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen WC, et al. Cellular kinetics of perivascular MSC precursors. Stem cells international. 2013;2013:983059. doi: 10.1155/2013/983059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bronckaers A, et al. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells as a pharmacological and therapeutic approach to accelerate angiogenesis. Pharmacol Therapeut. 2014 Mar 1; doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.02.013. pii: S0163-7258(0114)00052–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nassiri SM, Rahbarghazi R. Interactions of mesenchymal stem cells with endothelial cells. Stem cells and development. 2014;23:319–332. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, et al. Over-expression of PDGFR-β promotes PDGF-induced proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis of EPCs through PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. PloS one. 2012;7:e30503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiedler J, Etzel N, Brenner RE. To go or not to go: Migration of human mesenchymal progenitor cells stimulated by isoforms of PDGF. J Cell Biochem. 2004;93:990–998. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caplan AI, Correa D. PDGF in Bone Formation and Regeneration: New Insights into a Novel Mechanism Involving MSCs. J Orthopaed Res. 2011;29:1795–1803. doi: 10.1002/jor.21462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kreja L, et al. Non-resorbing osteoclasts induce migration and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109:347–355. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez-Fernandez MA, Gallois A, Riedl T, Jurdic P, Hoflack B. Osteoclasts control osteoblast chemotaxis via PDGF-BB/PDGF receptor beta signaling. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kubota K, Sakikawa C, Katsumata M, Nakamura T, Wakabayashi K. Platelet-derived growth factor BB secreted from osteoclasts acts as an osteoblastogenesis inhibitory factor. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:257–265. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakagami N, et al. Reduced osteoblastic population and defective mineralization in osteopetrotic (op/op) mice. Micron. 2005;36:688–695. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hellstrom M, Kalen M, Lindahl P, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development. 1999;126:3047–3055. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gelb BD, Shi GP, Chapman HA, Desnick RJ. Pycnodysostosis, a lysosomal disease caused by cathepsin K deficiency. Science. 1996;273:1236–1238. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5279.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen W, et al. Novel pycnodysostosis mouse model uncovers cathepsin K function as a potential regulator of osteoclast apoptosis and senescence. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:410–423. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brixen K, et al. Bone Density, Turnover, and Estimated Strength in Postmenopausal Women Treated With Odanacatib: A Randomized Trial. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013;98:571–580. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cusick T, et al. Odanacatib treatment increases hip bone mass and cortical thickness by preserving endocortical bone formation and stimulating periosteal bone formation in the ovariectomized adult rhesus monkey. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:524–537. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiang A, et al. Changes in micro-CT 3D bone parameters reflect effects of a potent cathepsin K inhibitor (SB-553484) on bone resorption and cortical bone formation in ovariectomized mice. Bone. 2007;40:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmer JT, et al. Design and synthesis of tri-ring P3 benzamide-containing aminonitriles as potent, selective, orally effective inhibitors of cathepsin K. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7520–7534. doi: 10.1021/jm058198r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao X, Guan JL. Focal adhesion kinase and its signaling pathways in cell migration and angiogenesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63:610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryu J, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate as a regulator of osteoclast differentiation and osteoclast-osteoblast coupling. Embo J. 2006;25:5840–5851. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pederson L, Ruan M, Westendorf JJ, Khosla S, Oursler MJ. Regulation of bone formation by osteoclasts involves Wnt/BMP signaling and the chemokine sphingosine-1-phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:20764–20769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805133106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lotinun S, et al. Osteoclast-specific cathepsin K deletion stimulates S1P-dependent bone formation. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:666–681. doi: 10.1172/JCI64840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roche B, et al. Parathyroid Hormone 1-84 Targets Bone Vascular Structure and Perfusion in Mice: Impacts of its Administration Regimen and of Ovariectomy. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1608–1618. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao Q, et al. Mice with increased angiogenesis and osteogenesis due to conditional activation of HIF pathway in osteoblasts are protected from ovariectomy induced bone loss. Bone. 2012;50:763–770. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shih TT, et al. Correlation of MR lumbar spine bone marrow perfusion with bone mineral density in female subjects. Radiology. 2004;233:121–128. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2331031509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seeman E, Delmas PD. Bone quality--the material and structural basis of bone strength and fragility. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;354:2250–2261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra053077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mackie EJ, Tatarczuch L, Mirams M. The skeleton: a multi-functional complex organ: the growth plate chondrocyte and endochondral ossification. J Endocrinol. 2011;211:109–121. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chatani M, Takano Y, Kudo A. Osteoclasts in bone modeling, as revealed by in vivo imaging, are essential for organogenesis in fish. Dev Biol. 2011;360:96–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Witten PE, Huysseune A. A comparative view on mechanisms and functions of skeletal remodelling in teleost fish, with special emphasis on osteoclasts and their function. Biol Rev. 2009;84:315–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seeman E. The periosteum - a surface for all seasons. Osteoporosis Int. 2007;18:123–128. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0296-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friedlaender GE, Lin S, Solchaga LA, Snel LB, Lynch SE. The role of recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB (rhPDGF-BB) in orthopaedic bone repair and regeneration. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:3384–3390. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319190005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Graham S, et al. Investigating the role of PDGF as a potential drug therapy in bone formation and fracture healing. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2009;18:1633–1654. doi: 10.1517/13543780903241607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Costa AG, Cusano NE, Silva BC, Cremers S, Bilezikian JP. Cathepsin K: its skeletal actions and role as a therapeutic target in osteoporosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:447–456. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boonen S, Rosenberg E, Claessens F, Vanderschueren D, Papapoulos S. Inhibition of cathepsin K for treatment of osteoporosis. Current osteoporosis reports. 2012;10:73–79. doi: 10.1007/s11914-011-0085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dossa T, et al. Osteoclast-specific inactivation of the integrin-linked kinase (ILK) inhibits bone resorption. J Cell Biochem. 2010;110:960–967. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saftig P, et al. Impaired osteoclastic bone resorption leads to osteopetrosis in cathepsin-K-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13453–13458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu X, et al. Inhibition of Sca-1-positive skeletal stem cell recruitment by alendronate blunts the anabolic effects of parathyroid hormone on bone remodeling. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhen G, et al. Inhibition of TGF-beta signaling in mesenchymal stem cells of subchondral bone attenuates osteoarthritis. Nat Med. 2013;19:704–712. doi: 10.1038/nm.3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Duvall CL, Taylor WR, Weiss D, Guldberg RE. Quantitative microcomputed tomography analysis of collateral vessel development after ischemic injury. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2004;287:H302–310. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00928.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang Y, et al. The hypoxia-inducible factor alpha pathway couples angiogenesis to osteogenesis during skeletal development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1616–1626. doi: 10.1172/JCI31581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qiu T, et al. TGF-beta type II receptor phosphorylates PTH receptor to integrate bone remodelling signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:224–U229. doi: 10.1038/ncb2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.