Abstract

Background

A current proposal for the DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) definition is to remove fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and sleep disturbance from the list of associated symptoms, and to require the presence of one of two retained symptoms (restlessness or muscle tension) for diagnosis. Relevant evaluations in youth to support such a change are sparse.

Methods

The present study evaluated patterns and correlates of the DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms in a large outpatient sample of anxious youth (N=650) to empirically consider how the proposed diagnostic change might impact the prevalence and sample composition of GAD in children.

Results

Logistic regression found irritability to be the most associated, and restlessness to be the least associated, with GAD diagnosis. Fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and sleep disturbances—which have each been suggested to be nonspecific to GAD due to their prevalence in depression—showed sizable associations with GAD even after accounting for depression and attention problems. Among GAD youth, 10.9% would not meet the proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion. These children were comparable to GAD youth who would meet the proposed criteria with regard to clinical severity, symptomatology, and functioning.

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of youth with excessive, clinically impairing worry may be left unclassified by the DSM-5 if the proposed GAD associated symptoms criterion is adopted. Despite support for the proposed criterion change in adult samples, the present findings suggest that in children it may increase the false negative rate. This calls into question whether the proposed associated symptoms criterion is optimal for defining childhood GAD.

Keywords: Anxiety disorders, Children, Classification, Diagnosis, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5

Whereas GAD definitions across DSM iterations have historically been marked by particularly poor reliability and diagnostic specificity,1–5 the reliability of DSM-IV GAD has substantially improved and is now comparable to the reliability of depression.6 The reliability of DSM-IV GAD is particularly impressive in youth samples.7–9 Nonetheless, systematic efforts are currently underway to improve upon the reliability and validity of the DSM-IV GAD definition for the upcoming DSM-5.10

One key area for proposed GAD definition change concerns the associated symptoms criterion. To distinguish individuals with GAD from high worriers who may not merit clinical attention, the DSM-IV GAD definition includes a set of 6 associated symptoms—i.e., restlessness, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance. Adult DSM-IV GAD diagnosis requires the presence of three such symptoms, whereas child diagnosis only requires one. A current proposal for DSM-5 GAD is to remove fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and sleep disturbance from the list of possible associated symptoms, and to require the presence of one of only two retained symptoms (restlessness or muscle tension) for GAD diagnosis.10,11 The theoretical rationale and empirical basis for this proposal is three-fold:10 (1) reducing the number of required associated symptoms, or reducing the criterion altogether, has a negligible impact upon GAD diagnostic rates;12–14 (2) for maximal relevance, a revised definition should not include associated symptoms rarely present in GAD; and (3) following Kubarych et al.,15 the retained associated symptoms should be specific to GAD (i.e., not shared by neighboring conditions such as depression). Incorporating both symptom prevalence and symptom specificity into diagnostic decision-making simultaneously recognizes that the most prevalent symptoms among GAD cases may not necessarily have meaningful diagnostic value, whereas the associated symptoms most uniquely associated with GAD diagnosis may not be relevant to a meaningful proportion of GAD cases.

Before GAD definition changes are implemented, it is important to evaluate the prevalence of restlessness and muscle tension as associated symptoms among child GAD cases, as well as the extent to which these symptoms, relative to the other associated symptoms, overlap with other defined disorders. Although empirical work has shown some support for the proposed associated symptom criterion change in adult samples,10,16 relevant evaluations in youth are sparse, and have not necessarily supported the proposed associated symptoms change for DSM-5 GAD. Regarding the prevalence of the associated symptoms among GAD youth, previous child research using self-reports does suggest that restlessness may be one of the two most prevalent associated symptoms among GAD cases.17,18 However, other child-report research and/or research using parent-reports finds that irritability, trouble concentrating, or sleep difficulties—all currently under consideration for removal in the DSM-5 GAD definition—may be the most common associated symptoms among GAD youth.18,19 The particularly high prevalence of irritability among GAD youth, relative to the other associated symptoms, has been replicated across multiple samples. Moreover, research suggests that muscle tension, which is to be retained in the DSM-5 GAD definition proposal, may actually be the least prevalent associated symptom among child GAD cases.18,19

Regarding the specificity (i.e., distinctiveness) of associated symptoms to GAD, less empirical work with child samples is available. There is some evidence that restlessness has relatively high diagnostic value among adolescents, but trouble concentrating and sleep disturbance also have high diagnostic value across both children and adolescents.20 Using child self-reports in pre-adolescent samples, irritability and sleep disturbances have shown the highest diagnostic value—specifically, these two symptoms have been associated with 15 and 14 times the odds of meeting criteria for GAD, whereas restlessness was associated with 3 times the odds and muscle tension was not associated with any increased odds.20 Previous research also suggests that muscle tension may show particularly poor negative predictive power,18 with only one-third of youth without muscle tension actually not meeting criteria for GAD. It has been argued that fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and sleep disturbance each overlap with symptoms of depression and therefore should be removed for non-specificity to GAD, 10 although importantly no research has evaluated whether relationships between these symptoms and GAD diagnosis in youth meaningfully attenuate after accounting for depression. Similarly, difficulty concentrating may overlap with symptoms of child attention problems. However, no research has evaluated whether the relationship between this associated symptom and GAD diagnosis meaningfully attenuates after accounting for attention problems.

In short, it remains unclear whether the associated symptoms criterion change proposed for the DSM-5 definition offers incremental clinical relevance and diagnostic value with regard to youth. The largest evidence to date supporting the proposed associated symptoms change did not include youth below the age of 16.16 Research in this area with youth has not necessarily supported the proposed changes, but has been largely confined to relatively small samples,17–19 and has not been conducted with direct reference to GAD cases who would and would not meet the proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion change. Importantly, research to date with child samples has also not evaluated the extent to which each of the associated symptoms is linked with GAD diagnosis, even after accounting for depression and attention problems—a key analysis in the empirical consideration of the specificity of each associated symptom to GAD. In the absence of such data, removal of various symptoms due to an appearance of nonspecificity to GAD may be problematic.

The present study evaluated patterns and correlates of the DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms criterion in a large outpatient treatment-seeking sample of anxious youth to empirically consider how the proposed diagnostic change might impact the prevalence and sample composition of GAD in children. Specifically, we examined the correlates of the proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion change (presence of restlessness and/or muscle tension), relative to the DSM-IV associated symptoms criterion, as well as other potential constellations of associated symptoms not under current consideration. We also compared GAD youth who would and would not meet the proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion on a range of measures of clinical severity, symptomatology, and functioning.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 650 consecutive treatment-seeking youth meeting diagnostic criteria for a DSM-IV anxiety disorder, and their mothers, presenting for services at a university-affiliated center for the treatment of anxiety and related disorders in New England (2004–2010). Children (46.2% male) ranged in age from 5 to 19 years (Mage=12.14, SDage=3.26); 81.7% self-identified as non-Hispanic Caucasian. Families ranged in resources: 20.8% were at or below 300% of the national poverty line for their year (e.g., in 2007 $63,609 for a family of 4; $75,240 for a family of 5) whereas 13.2% of households earned at least 600% of the national poverty line at their year of assessment (e.g., in 2007 $127,218 for a family of 4; $150,480 for a family of 5). Parents of the majority of children were married or cohabitating (82.3%); 11.2% of children’s parents were previously but no longer married, and 2.9% were never married. Regarding psychotropic medications, 20.2% of youth were taking antidepressant medication, 8% were taking stimulant or other ADHD medication, 4.5% were taking a sedative or hypnotic medication, 4.3% were taking an antipsychotic medication, and 2.3% were taking a mood stabilizer.

Among the 650 youth, 239 met diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV GAD, either as a principal or sub-principal diagnosis (i.e., GAD youth), whereas 411 met diagnostic criteria for a DSM-IV anxiety disorder but did not meet criteria for GAD (i.e., AD youth). AD youth met diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV social anxiety disorder (SocAD; 28.7%), separation anxiety disorder (SepAD; 21.2%), panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (PDA; 15.6%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; 19.0%), specific phobia (SP; 27.0%), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; 1.7%) (group memberships across the ADs overlap due to comorbidity). Depressive disorders were also common (12.6%). Sub-principal comorbidities were high among GAD youth as well: 36.0% had SocAD, 18.8% had SepAD, 5.9% had PDA, 15.9% had OCD, and 20.5% had a depressive disorder.

Measures

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children and Parents for DSM-IV (ADIS-C/P)

The ADIS-C/P21 is a semistructured diagnostic interview that assesses child psychopathology in accordance with DSM–IV criteria, with particularly thorough coverage of the internalizing disorders. The ADIS-C (child version) and the ADIS-P (parent version) collect data on children’s and parents’ reports of child anxiety, respectively. Child and parent diagnostic profiles are integrated into a composite diagnostic profile using the “or rule” at the diagnostic level, in which a diagnosis is included in the composite profile if either the parent(s) or child endorsed sufficient diagnostic criteria for that disorder. Diagnoses are assigned a clinical severity rating (CSR) ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 8 (extremely severe symptoms), with CSRs of 4 or above used to characterize disorders that meet full diagnostic criteria and CSRs of 3 and below used to characterize subthreshold presentations. The ADIS-IV-C/P was also used to evaluate the presence of each of the associated symptoms.

The ADIS-C/P has been the most widely used diagnostic interview in clinical research evaluating child anxiety, likely due to its strong reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change.22,23 In age ranges comparable to those of the present sample, the interview has demonstrated good reliability for parent (κrange from 0.65-0.88) and child diagnostic profiles (κ range from 0.63 to 0.88).8,22 Diagnostic reliability was strong in the present sample (κ for all anxiety disorders ≥ .70).

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

The CBCL24 is a standardized instrument for assessing behavioral and emotional problems and competencies, demonstrating excellent psychometric properties. The instrument assesses 120 emotional, behavioral, and social problems reported by parents of children ages 6 to 18. Parents rate each item for the past 6 months as 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), or 2 (very true or often true). Empirically based syndrome scales, normed for age and gender, are generated, including three broadband dimensions: Internalizing Problems, Externalizing Problems, and Total Problems, as well as eight syndrome scales and six DSM-oriented scales. T-scores below 65 fall in the normative range. The following subscales have been linked to diagnosed anxiety disorders in previous empirical work,25–28 and accordingly were included in the present analysis: Internalizing Problems, Total Problems, Anxious/Depressed Symptoms, Somatic Complaints, and Social Problems. The Attention Problems subscale was included for analyses evaluating the specificity of associations between the DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms and GAD diagnosis. All subscales showed high internal consistency in the present sample (all Cronbach’s alphas ≥ .80).

Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI)

The CDI29 is a widely used self-rating scale of depressive symptomatology in children. For each item, the child is asked to endorse one of three statements that best describes how he or she has typically felt over the past 2 weeks (e.g., “I am sad once in a while,” I am sad many times,” or “I am sad all the time”). Each response is scored as either 0 (asymptomatic), 1 (somewhat symptomatic), or 2 (clinically symptomatic), contributing to an overall CDI score that can range from 0 to 54. The scale has demonstrated excellent internal consistency in both clinical and nonclinical samples (α > .80)30–32 and acceptable test-retest reliability identified in both clinical and nonclinical samples.29,33–35 Internal consistency was high in the present sample (α = .89). Research supports the use of the CDI as a continuous measure of depressive symptomatology in anxious youth.36

Procedure

Participants were recruited at Boston University’s Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders, a university-affiliated outpatient center for the treatment of emotional disorders in New England. Families completed an initial telephone screening as part of clinic procedures. Children were excluded with current psychotic symptoms, suicidal or homicidal risk requiring crisis intervention, 2 or more hospitalizations for severe psychopathology (e.g., psychosis) within the previous 5 years, or moderate to severe intellectual impairments. Children on psychotropic medications were required to be stabilized at least one month on current dose prior to participation. Participating families were administered the ADIS-C/P and mothers and children completed the CBCL and CDI, respectively, as part of a prescreening battery for treatment. After obtaining informed consent, a diagnostician conducted separate child and parent interviews, and then integrated diagnostic profiles using the “or rule” to generate a composite diagnostic profile. For each case, interview material was presented and reviewed at a weekly diagnostician staff meeting, during which time symptoms were reviewed and a team consensus on the diagnostic profile was obtained. Consistent with ADIS-C/P guidelines, diagnoses were generated in strict accordance with DSM-IV. Diagnosticians included a panel of 22 clinical psychologists, postdoctoral associates, and doctoral candidates specializing in the assessment and treatment of pediatric anxiety disorders. All diagnosticians met internal certification and reliability procedures, developed in collaboration with one of the ADIS-C/P authors: observing three complete interviews, collaboratively administering three interviews with a trained diagnostician, and conducting supervised interviews until achieving the reliability criterion (i.e., full diagnostic profile agreement on three of five consecutive supervised assessments). Demographic information was obtained from parent report. As in previous research,37 household income was used to compute a poverty index ratio (i.e., household income divided by U.S. poverty threshold in the interview year), resulting in four index ratio categories: <1.5; 1.5 < 3.0; 3.0 to < 6.0; and ≥ 6.0.

GAD youth sub-classification

Among GAD youth, children were further classified into one of two groups: (1) those meeting the proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion of showing restlessness and/or muscle tension, and (2) those not meeting the proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion.

Data analysis

First, we evaluated demographic differences between the GAD and AD youth via chi-square tests. We then computed the percentage of GAD and AD cases presenting with each of the DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms, as well as the total numbers of associated symptoms. Logistic regression analyses using the associated symptoms to predict GAD diagnosis were conducted, controlling for demographic correlates of group membership (age, race/ethnicity). To further evaluate the specificity of each DSM-IV GAD associated symptom to GAD, we conducted logistic regression analyses using associated symptoms to predict GAD diagnosis, controlling for both depression (CDI total score) and attention problems (CBCL attention problems), as well as the demographic correlates of group membership (age, race/ethnicity).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was conducted to evaluate the diagnostic utility of the DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms. ROC analysis can provide a depiction of a symptom domain’s specific link to diagnosis by demonstrating the limits of the symptoms to discriminate over the complete spectrum of symptoms (for a review of ROC analysis, see Zweig and Campbell).38 For each associated symptom, sensitivity was operationalized as the rate of GAD youth with that associated symptom, and specificity was operationalized as the rate of AD youth who do not have that associated symptom. For each associated symptom the positive predictive power was operationalized as the rate of youth with the symptom who in fact have GAD, whereas negative predictive power was operationalized as the rate of youth without that associated symptom who do not have GAD. For further descriptive purposes, for each associated symptom we computed odds ratios (ORs), as well as the overall correct classification rate—i.e., the percentage of overall cases who either (a) had GAD as well as that associated symptom, or (b) did not have GAD and did not have that symptom. Consistent with previous work,20,39–42 values ranging from .00 to .29 were considered low, values ranging from .30 to .69 were considered moderate, and values ranging from .70 to 1.0 were considered high.

Plotting all of the sensitivities and corresponding specificities at each particular cut score (i.e., number of associated symptoms required for diagnosis) provides a curve, the area under which ranges from 1.0 (perfect separation of associated symptom counts of the two groups) to .5 (no apparent distributional difference between the two groups on associated symptoms counts). This area under the curve (AUC) provides a quantitative estimate of diagnostic accuracy and, consequently, the overall utility of the GAD associated symptoms in distinguishing children with diagnosed GAD from children with other diagnosed anxiety disorders.

Finally, to evaluate the clinical impact of the proposed associated symptoms criterion change for DSM-5 GAD, t-tests were conducted comparing GAD youth who do and do not meet the proposed criterion change across various key clinical dimensions (i.e., total number of clinical diagnoses, GAD clinical severity, internalizing symptoms, anxious/depressed symptoms, social problems, somatic problems, and total problems).

Results

Differences between GAD and AD youth

GAD and AD youth did not differ with regard to age, parental marital status, or poverty/income ratio. Relative to AD youth, significantly higher proportions of GAD youth were female [59.4% vs 50.6%; χ2(1, N = 650)=4.72, p=.03] and minorities [23.0% vs. 15.6%; χ2(1, N =650)=5.59, p=.02]. Psychotropic medication treatment was comparable across the two groups. On average, GAD youth presented with more clinical diagnoses (average number of clinical diagnoses was 2.5 relative to 1.7 for AD youth), F(1, 648)=77.48, p<.001, and CBCL Internalizing Problems, F(1, 647) = 36.25, p<.001.

GAD youth showed a significantly greater number of the associated symptoms than AD youth, t(648)=13.6, p <.0001. Specifically, GAD youth exhibited an average of 4.6 DSM-IV associated symptoms (SD = 1.5), whereas AD youth exhibited an average of 2.4 associated symptoms (SD = 2.1). Among GAD youth, each associated symptom was present in at least 50% of cases (see Table 1). Irritability was the most common associated symptom (present in >90% of cases), whereas muscle tension was the least common. Muscle tension was also the least common associated symptom among AD cases. Logistic regression analyses, controlling for significant demographic correlates of group membership (i.e., gender and race/ethnicity), found significant correlations between each of the associated symptoms and GAD diagnosis (see Table 1). The largest association was found for irritability—after accounting for gender and race/ethnicity, the presence of irritability increased a child’s odds of having GAD, relative to another anxiety disorder, by roughly 10 times. After accounting for gender and race/ethnicity, restlessness showed the very lowest association with GAD diagnosis. Across potential quantities of associated symptoms required for diagnosis, the presence of 6 associated symptoms showed the largest association with GAD. Specifically, after accounting for gender and race/ethnicity, the presence of all six DSM-IV associated symptoms increased a child’s odds of having GAD, relative to another anxiety disorder, by about 6 times (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Number and percentage of cases with and without DSM-IV GAD meeting each of the DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms in a child anxiety treatment-seeking sample (N = 650)

| GAD (N=239) |

Non-GAD anxiety disorders (N=411) |

Significance testa | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Model | B | SE | Wald | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp (B) |

|

| Restlessness | 204 | 85.4 | 35 | 14.6 | 1 | −1.86 | .21 | 78.4*** | 0.2 | 0.1–0.2 |

| 2 | −1.82 | .25 | 52.4*** | 0.2 | 0.1–0.3 | |||||

| Feeling easily fatigued | 148 | 61.9 | 91 | 38.1 | 1 | 1.31 | .17 | 56.8*** | 3.7 | 2.6–5.2 |

| 2 | 1.29 | .21 | 38.0*** | 3.6 | 2.4–5.5 | |||||

| Difficulty concentrating | 199 | 83.3 | 40 | 16.7 | 1 | 1.69 | .20 | 70.6*** | 5.4 | 3.7–8.1 |

| 2 | 1.69 | .24 | 50.0*** | 5.4 | 3.4–8.7 | |||||

| Irritability | 218 | 91.2 | 21 | 8.8 | 1 | 2.30 | .25 | 85.8*** | 10.1 | 6.2–16.5 |

| 2 | 2.48 | .32 | 62.0*** | 12.0 | 6.5–22.2 | |||||

| Muscle Tension | 123 | 51.5 | 116 | 48.5 | 1 | 1.50 | .18 | 65.2*** | 4.3 | 3.0–6.2 |

| 2 | 1.47 | .22 | 46.5*** | 4.4 | 2.9–6.7 | |||||

| Sleep disturbance | 196 | 82.0 | 43 | 18.0 | 1 | 1.70 | .20 | 75.1*** | 5.6 | 3.8–8.2 |

| 2 | 1.80 | .24 | 54.8*** | 6.1 | 3.8–9.8 | |||||

| 1 DSM-IV GAD associated symptom | 12 | 5.0 | 25 | 6.1 | 1 | −2.72 | 1.0 | 7.05** | 0.1 | 0.0–0.5 |

| 2 DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms | 9 | 3.8 | 34 | 8.3 | 1 | −0.80 | .39 | 4.3* | 0.5 | 0.2–1.0 |

| 3 DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms | 24 | 10.0 | 43 | 10.5 | 1 | −0.03 | .27 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.6–1.6 |

| 4 DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms | 49 | 20.5 | 75 | 18.2 | 1 | 0.15 | .21 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.8–1.7 |

| 5 DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms | 69 | 28.9 | 58 | 14.1 | 1 | 0.88 | .20 | 18.8*** | 2.4 | 1.6–3.6 |

| 6 DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms | 76 | 31.8 | 30 | 7.3 | 1 | 1.8 | .24 | 56.9*** | 6.1 | 3.8–9.8 |

Note: Table shows number of subjects (n), percent (%) of patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and other anxiety disorders (non-GAD) reporting the six associated symptoms of GAD and a combination of them. The Table also depicts the results of logistic regression analyses using the associated symptoms to predict presence or absence of a GAD diagnosis, Model 1 controls for age, race/ethnicity; Model 2 controls for age, race/ethnicity, depression, and attention problems.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Diagnostic utility of existing and proposed GAD associated symptoms criteria

To evaluate the specificity of each of the associated symptoms to GAD diagnosis after accounting for symptom constellations that may share phenomenological overlap, logistic regression analyses, controlling for gender and race/ethnicity, as well as for depression and attention problems, were conducted (see Table 1, Model 2 for each symptom). After accounting for depression and attention problems, each of the 6 DSM-IV symptoms retained significant and sizable associations with GAD diagnosis. The largest association was still found for irritability even after accounting for depression and attention problems; the presence of irritability increased a child’s odds of having GAD by about 12 times. Fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and sleep disturbances—each of which have been suggested to be nonspecific to GAD due to their prevalence in depression—showed sizable associations with GAD diagnosis even after accounting for depression and attention problems (each still associated with increasing a child’s odds of having GAD by roughly 4–6 times).

Table 2 presents the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive power, and negative predictive power of each associated symptom—as well as each quantity of associated symptoms—for distinguishing GAD from AD youth. Base rates, kappa coefficients, odds ratios, and overall correct classification rates corresponding to each associated symptom are also reported. Irritability was the most sensitive associated symptom and muscle tension was the least sensitive, whereas muscle tension showed the greatest specificity to GAD and irritability showed the least specificity (muscle tension was the only associated symptom that did not show high sensitivity to GAD). Relative to the other DSM-IV associated symptoms, the proportion of children showing muscle tension had the highest rate of GAD (PPP). In contrast, the proportion of children not showing irritability showed the lowest rate of GAD (NPP). Overall correct classification rates were in the moderate to almost high range for each of the associated symptoms.

Table 2.

Diagnostic utility properties of the associated symptoms for distinguishing GAD (N=239) from non-GAD AD (N=411) youth

| Associated Symptom | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPP | NPP | Base rate | κ | OR | OCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restlessness | .854 | .523 | .51 | .86 | .615 | .33 | 6.39 | .645 |

| Feeling easily fatigued | .619 | .693 | .54 | .76 | .422 | .30 | 3.68 | .666 |

| Difficulty concentrating | .833 | .523 | .50 | .84 | .608 | .31 | 5.46 | .637 |

| Irritability | .912 | .494 | .51 | .91 | .655 | .35 | 10.13 | .648 |

| Muscle Tension | .515 | .803 | .60 | .74 | .314 | .33 | 4.32 | .697 |

| Sleep disturbance | .820 | .550 | .51 | .84 | .586 | .33 | 5.57 | .649 |

| 1 DSM-IV GAD associated symptom | 1.00 | .355 | .47 | 1.0 | .775 | .27 | -- | .592 |

| ≥ 2 DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms | .950 | .416 | .49 | .93 | .714 | .31 | 13.48 | .612 |

| ≥ 3 DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms | .912 | .499 | .51 | .91 | .652 | .35 | 10.33 | .651 |

| ≥ 4 DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms | .812 | .603 | .54 | .85 | .549 | .38 | 6.56 | .680 |

| ≥ 5 DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms | .607 | .786 | .62 | .77 | .358 | .40 | 5.66 | .720 |

| ≥ 6 DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms | .318 | .927 | .72 | .70 | .163 | .28 | 5.92 | .703 |

| GAD associated symptoms criterion | .891 | .293 | .88 | .32 | .864 | .19 | 3.39 | .803 |

| proposed for DSM-51 | ||||||||

Note: Sensitivity = % of GAD youth with each associated symptom; Specificity = % of AD youth who do not have that associated symptom; PPP = positive predictive power (% of youth with that associated symptom who in fact have GAD); NPP = negative predictive power (% of youth without that associated symptom who do not have GAD; Base Rate = % of GAD+AD youth showing associated symptom; κ= Kappa; OR = Ratio of odds of GAD diagnosis if symptom present to odds of no diagnosis if symptom not present; OCC = Overall Correct Classification.

Restlessness and/or muscle tension

Table 2 also presents the diagnostic utility estimates for each of six potential cut scores in the number of symptoms required for GAD diagnosis (i.e., 1 required symptom, 2 symptoms, 3 symptoms, 4 symptoms, 5 symptoms, or 6 symptoms). As the cut score increases, the rate of GAD youth showing that many associated symptoms (i.e., sensitivity) decreases, with indices ranging from 1.0 (when employing a cut score of 1 required associated symptom) to .318 (when employing a cut score of 6 associated symptoms). Alternatively, the rate of AD youth not showing that many associated symptoms (i.e., specificity) increases as the cut score increases, with indices ranging from .355 (when employing a cut score of 1 required associated symptom) to .927 (when employing a cut score of 6 associated symptoms). Children exhibiting all 6 of the associated symptoms also showed the highest rate of GAD diagnosis, but it was a cut score of 5 required symptoms that resulted in the highest percentage of overall cases who either (a) had GAD as well as that many associated symptoms, or (b) did not have GAD and did not have that many symptoms.

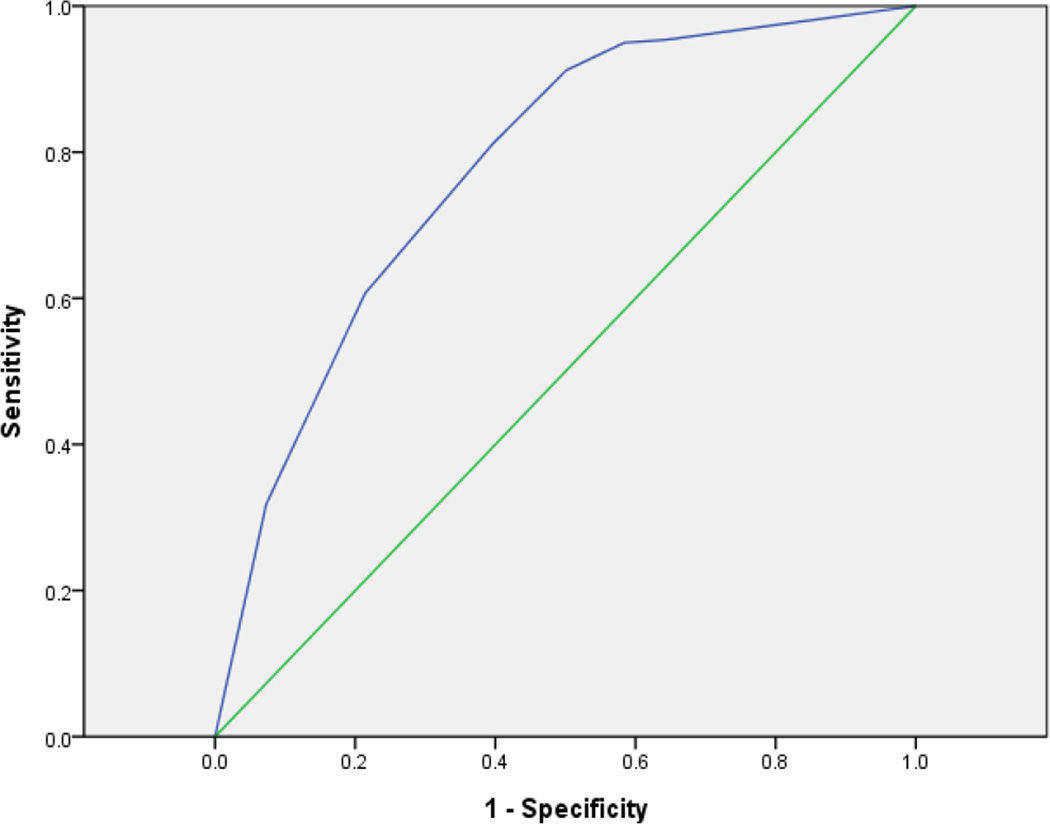

Figure 1 presents the ROC curve generated by plotting all of the sensitivities and corresponding 1-specificities at each potential cut score of required associated symptoms for GAD diagnosis. Across the entire range of cut scores, the associated symptoms demonstrated acceptable overall utility in distinguishing GAD from AD cases (AUC = .778, SD = .059). This AUC significantly differs from .5, or the null value that would indicate no apparent distributional difference between the two groups on the number of associated symptoms exhibited (p < .001).

Figure 1.

ROC plot of sensitivities and 1-specificities across the range of endorsed DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms in the prediction of GAD diagnosis

Analyses specifically evaluating the diagnostic utility of the proposed associated symptoms criterion change for DSM-5 GAD (i.e., presence of either restlessness or muscle tension) identified that this criterion showed higher sensitivity (.891) than any individual associated symptom, but lower sensitivity than a requirement that 1, 2, or 3 of the 6 DSM-IV symptoms be present. Specificity (.499) was lower than all individual associated symptoms except for irritability, but was higher than specificity associated with a requirement that 1 or 2 of the 6 DSM-IV symptoms be present. Positive predictive power associated with the proposed criterion change (.51) did not improve upon the PPP associated with any individual associated symptom, but was higher than PPP associated with a requirement that 1 or 2 of the 6 DSM-IV symptoms be present. Negative predictive power was high (.89) but not as high as NPP for irritability, nor a requirement that 1, 2, or 3 of the 6 DSM-IV symptoms be present.

Evaluating the proposed criterion relative to other pairwise combinations of associated symptoms

To evaluate whether the proposed associated symptoms criterion change for DSM-5 GAD shows more favorable diagnostic utility properties than other potential pairwise combinations of associated symptoms, sensitivity, specificity, PPP, and NPP were each computed for all possible criteria requiring one of two specific associated symptoms (with 6 symptoms, there are 15 possible pairwise combinations). Diagnostic utility indices reflecting the GAD associated symptoms changes proposed for DSM-5 are presented in Table 2. Across the 15 possible pairwise associated symptoms criteria, the proposed DSM-5 criterion ranked 11th in sensitivity, 3rd in specificity, 2nd in PPP, and 9th in NPP. The most sensitive pairwise combination was a requirement of restlessness or irritability (.950) and the combination with the highest specificity was a requirement of fatigue or muscle tension (.613). This latter combination also showed the highest PPP relative to other possible combinations (.52). Requiring either restlessness or irritability showed the highest NPP (.93).

Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with existing and proposed associated symptom criterion

Among GAD youth, 10.9% (N=26) would not meet the proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion. These children were comparable to the remaining GAD youth with regard to gender, race/ethnicity, poverty/income ratio, parental marital status, age, and total number of diagnoses in their diagnostic profile (all ps>.05). GAD youth who would not meet the proposed associated symptoms criterion for DSM-5 GAD showed comparable GAD clinical severity to GAD youth who would meet the proposed criteria (see Table 3). Groups also showed comparable levels of internalizing symptoms, anxiety/depression, social problems, somatic problems, and overall total problems.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical differences between DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) cases that do and do not meet the proposed DSM-5 associated symptom criterion in a child anxiety treatment-seeking sample (N = 239)

| DSM-IV GAD cases (N = 239) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases meeting proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion (n = 213) |

Cases not meeting proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion (n = 26) |

Significance test | |||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Child Gender | χ2(1, N =239) = 0.52, p=.47 | ||||

| Male | 106 | 49.8 | 11 | 42.3 | |

| Female | 107 | 50.2 | 15 | 57.7 | |

| Child Race/Ethnicity | χ2(1, N =239) = 0.74, p=.39 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Caucasian | 171 | 80.3 | 19 | 73.1 | |

| Minority | 42 | 19.7 | 7 | 26.9 | |

| Parent Marital Status | χ2(1, N =239)= 0.57, p=.45 | ||||

| Married/Cohabitating | 176 | 82.6 | 23 | 88.5 | |

| No longer/ never married | 37 | 17.4 | 3 | 11.5 | |

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Child Age | 12.3 | 3.2 | 11.6 | 3.4 | t (237)=1.05 ; p=.30 |

| Poverty Index Ratio | 4.5 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 1.8 | t (237)=1.56 ; p=.12 |

| Total # of clinical diagnoses | 2.5 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1.1 | t (237)=0.44 ; p=.66 |

| GAD CSR | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.3 | t (237)=0.19; p=.85 |

| CBCL-Internalizing | 70.5 | 7.7 | 71.8 | 6.3 | t (237)=0.83; p=.41 |

| CBCL-Anxious/Depressed | 74.1 | 9.4 | 74.7 | 7.3 | t (237)=0.32; p=.75 |

| CBCL-Social Problems | 59.6 | 8.0 | 59.8 | 6.2 | t (237)=0.12; p=.90 |

| CBCL-Somatic | 65.4 | 9.5 | 63.3 | 9.3 | t (237)=1.07; p=.29 |

| CBCL-Total Problems | 64.3 | 7.7 | 65.4 | 6.1 | t(237)=0.70; p=.48 |

Note: CSR = clinical severity rating; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory

Discussion

To evaluate the current DSM-5 proposal for changes in the GAD associated symptoms criterion, we evaluated patterns and correlates of the DSM-IV GAD associated symptoms in a large outpatient sample of anxious youth. Our results suggest that a substantial proportion of youth with excessive, clinically impairing worry about a number of events or activities may be left unclassified by the DSM-5 if the proposed GAD associated symptoms criterion is adopted. Whereas the majority of previous empirical work supporting the proposed GAD associated symptoms criterion change has come from adult samples,10,16 the present findings from a child treatment-seeking sample suggest that roughly 1 out of every 9 youth meeting criteria for DSM-IV GAD do not meet the proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion. These children show considerably elevated clinical severity, internalizing symptoms, and total problems, and at levels comparable to children meeting criteria for DSM-IV GAD who do meet the proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion.

The primary rationale for adopting the proposed associated symptoms criterion is to improve upon the sensitivity and specificity of the GAD definition.10 From a sensitivity standpoint, similar to previous GAD research with children17,18 there was strong support in the present sample for the inclusion of restlessness as an associated symptom. However, from a sensitivity standpoint there was weak support for the inclusion of muscle tension, which showed the lowest prevalence among GAD cases and the least favorable sensitivity properties across the DSM-IV associated symptoms. This is also consistent with findings from previous work with child GAD samples.18 In contrast, muscle tension did show high specificity, with 4 out of every 5 youth without muscle tension not meeting criteria for DSM-IV GAD.

In the present sample, it was irritabiltiy that demonstrated the most favorable overall properties of diagnostic value. Relative to the other associated symptoms, irritiabiltiy showed the highest prevalence among GAD youth, and the lowest prevealence among AD youth (9 out of every 10 GAD youth, versus less than 1 out of every 10 AD youth, showed irritability). Irritability also showed the highest sensitivity to GAD, the lowest negative predictive power, and having irritability placed a child at the highest odds of having GAD. Importantly, although irritabilty is linked with depression,39 irritabiltiy showed the highest association with GAD, relative to the other associated symptoms, even after accounting for depression. These findings are consistent with other research supporting the highly favorable diagnostic properties of irritability in the diagnosis of child GAD.18–20 Taken together, the DSM-5 GAD definition may do well to retain irritability as an associated symptom, at least for the diagnosis of GAD in youth.

It has been suggested that fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and sleep difficulties should be removed from the definition of GAD due to their overlap with symptoms of depression.10 In the present sample, associations between these symptoms and GAD diagnosis persisted even after accounting for depression, suggesting that symptom overlap may not be a problem with regard diagnosing GAD definition in youth. Efforts to improve the specificity of the GAD definition on these grounds by removing these three symptoms may be unnecessarily conservative with regard to diagnosing childhood GAD. It may be that overlapping symptoms between GAD and depression are less relevant to accurate diagnosis in youth populations. Relatedly, the DSM-5 GAD definition under consideration adds several new behavioral symptoms. Among these proposed symptoms are repeated reassurance seeking and procrastination in behavior or decision making, both of which are asosciated with depression.40 Prior to finalizing the DSM-5 GAD definition, research similar to the present study is needed to evaluate relationships between these new symptoms under consideration and GAD diagnosis after accounting for variance due to depression.

Current rationale for the proposed associated symptoms criterion change10 cites research showing the negligible impact of removing the criterion altogether as supporting evidence for criterion modification.12,14 Similarly, research in child samples finds that removing the associated symptoms criterion would have a negligible impact on rates of child GAD.13 Importantly, although such work may support the full removal of an associated symptoms criterion altogether, such work does not directly speak to the utility of the specific modification proposed. Although work with older samples has shown some support for the proposed criterion,16 in the present sample, the proposed criterion shows less favorable sensitivity and negative predictive power than the current DSM-IV associated symptoms criterion. Although the proposed criterion did show mildly improved specificity and positive predictive power than the current associated symptoms criterion, the present findings may nonetheless call into question the incremental value of the proposed criterion with regard to youth. That is, for the gain of modestly improved specificity (.499 vs. .355) and positive predictive power (.51 vs .47), 11% of chilren with GAD-IV—children who show no less clinical severity or problems than other GAD-IV cases—will no longer meet the GAD definition. In the DSM-5, these children would presumably receive a diagnosis of Anxiety Disorder Not Elsewhere Categorized (previously Anxiety Disorder Not Otherwise Specified, DSM-IV: 300.00).

Diagnostic assessment provides an important communication function. Hours of evaluation are often distilled into diagnostic labels and/or numeric codes as shorthands to succinctly convey key information to other providers, to payers, and to review panels charged with evaluating quality of care. Evidence-based treatment strategies vary in meaningful ways across the child anxiety disorders, including whether or not there is strong support for the use of SSRIs, which SSRI is most supported for which anxiety disorder, and what the specific focus of cognitive-behavioral therapy should entail.41–44 As such, a diagnostic label or code indicating that an anxiety disorder is not specified regrettably does little to communicate important information suggesting an indicated treatment course. Moreover, clinical trials for childhood anxiety typically require a DSM-specified anxiety disorder for study inclusion,45 and so evidence supporting how best to intervene with children presenting with common and interfering, but unspecified, symptom presentations lags behind evidence supporting treatments for DSM-specified disorders. As noted elsewhere,13 future iterations of the DSM will do well to reduce the proportion of anxious youth with marked impairments who are left unspecified by the diagnostic manual. The present findings suggest that the proposed associated symptoms criterion may further this problem among youth who excessively worry about a number of events or activities.

The present findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, because this research was conducted in an outpatient specialty clinic for the treatment of anxiety disorders, results may not generalize to the general child population, to other treatment settings where children receive mental health care, to outpatient specialty settings of different sociodemographic make-up, or to adult populations. Second, many youth in the sample were being maintained on psychotropic medications, which could have impacted observed symptom and diagnostic presentations. Future work in this area would do well to evaluate samples who are not managed on psychotropic medications. Third, although including a comparison group of youth with anxiety disorders informs our understanding of the high-level specificity of the GAD associated symptoms relative to youth with neighboring conditions, including a comparison group of non-anxious youth instead may have yielded different utility properties. Future work would do well to evaluate the diagnostic value of the associated symptoms among GAD youth in the context of non-affected community youth. Fourth, given that the ADIS-IV-C/P was developed for correspondence with DSM-IV, it was not possible in the present work to evaluate properties of the new behavior symptoms proposed for DSM-5 GAD (behavioral avoidance, marked time/effort preparing for possible negative outcomes, procrastination in behavior or decision making, and reassurance seeking). Finally, although the sample is appropriately powered to identify significant differences among all group comparisons, it is possible that some of the differences that did not reach statistical significance would have in the context of a sample larger than 650 participants.

Despite these limitations, the present analysis suggests that 11% of seriously impaired treatment-seeking children with DSM-IV GAD would no longer meet diagnostic criteria for GAD if the proposed associated symptoms criteria are included in the DSM-5 GAD definition. This suggests that the proposed changes would increase the false negative rate. The DSM-5 aims to incorporate an increased developmental focus into the revised psychiatric nomenclature,46 by integrating explicit descriptions of developmental manifestations of disorders into the manual, and including these descriptions as part of criteria for each disorder. At present, the only shifting developmental focus for the transition from DSM-IV to DSM-5 GAD is the removal of the DSM-IV distinction that children are only required to show 1 of 6 associated symptoms whereas adults are required to show at least 3 of 6. Despite support for the proposed DSM-5 associated symptoms criterion in adult samples,16 the present work calls into question whether the proposed associated symptoms criterion is optimal for defining childhood GAD. For example, irritability demonstrated the most favorable properties of diagnostic value across the DSM-IV associated symptoms. As such, at a minimum there may be reason to retain irritabilty as an associated symptom in the definition of childhood GAD.

The definition of GAD has shifted across DSM iterations—perhaps more so than the majority of common anxiety disorders. As such, our understanding of GAD may lag somewhat behind the other anxiety disorders. Given the relatively strong reliability of DSM-IV GAD,6–9 prudence would suggest definition revisions should be restricted to only the very minimum number of changes necessary to offer clear improvements over exiting criteria sets. The present analysis suggests that with regard to treatment-seeking youth, the proposed associated symptoms change may not offer a clear improvement.

Acknowledgments

Funding/support: This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) K23 MH090247 (Dr. Comer), R01 MH068277 (Dr. Pincus), and R01 MH078308 (Dr. Hofmann).

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: No authors have competing financial interests to declare.

References

- 1.Comer JS, Kendall PC, Franklin ME, Hudson JL, Pimentel SS. Obsessing/worrying about the overlap between obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in youth. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;664:663–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Nardo PA, O’Brien GT, Barlow DH, et al. Reliability of DSM-III anxiety disorder categories using a new structured interview. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:1070–1074. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790090032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Nardo PA, Moras K, Barlow DH, et al. Reliability of DSMIII-R anxiety disorder categories: using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Revised (ADIS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:251–256. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820160009001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ, Martin MS, et al. Reliability of anxiety assessment, I: diagnostic agreement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1093–1101. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810120035007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID): II. Multisite test-retest reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:630–636. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080038006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: implications for the classification of emotional disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyneham H, Abbott M, Rapee R. Interrater reliability of the anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent version. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(6):731–736. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180465a09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman W, Saavedra L, Pina A. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV : Child and parent versions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas C, Dulcan M, Schwab-Stone M. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews G, Hobbs M, Stanley M, et al. Generalized worry disorder: A review of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder and options for DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:134–147. doi: 10.1002/da.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Development. E-05 Generalized Anxiety Disorder Proposed Revision. 2012 Available at: http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=167.

- 12.Beesdo-Baum K, Winkel S, Pine DS, Hoyer J, Hofler M, Lieb, Wittchen HU. The diagnostic threshold of generalized anxiety disorder in the community: A developmental perspective. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:962–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comer JS, Gallo KP, Korathu-Larson P, Pincus DB, Brown TA. Specifying child anxiety disorders not otherwise specified in the DSM-IV. Depress Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.21981. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruscio AM, Chiu WT, Roy-Byrne P, et al. Broadening the definition of generalized anxiety disorder: Effects on prevalence and associations with other disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:662–676. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubarych TS, Aggen SH, Hettema JM, et al. Endorsement frequencies and factor structure of DSM-III-R and DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorders symptoms in women: implications for future research, classification, clinical practice and comorbidity. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005;14:69–81. doi: 10.1002/mpr.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews G, Hobbs M. The effect of the draft DSM-5 criteria for GAD on prevalence and severity. Aus New Zealand J Psychiatry. 2010;44:784–790. doi: 10.3109/00048671003781798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Layne AE, Bernat DH, Victor AM, Bernstein GA. Generalized anxiety disorder in a nonclinical sample of children: symptom presentation and predictors of impairment. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tracey SA, Chorpita BF, Douban J, Barlow DH. Empirical evaluation of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder criteria in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Psychol. 1997;26(4):404–414. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2604_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendall PC, Pimentel SS. On the physiological symptom constellation in youth with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17:211–221. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pina AA, Silverman WK, Alfano CA, Saavedra LM. Diagnostic efficiency of symptoms in the diagnosis of DSM-IV: generalized anxiety disorder in youth. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43(7):959–967. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverman WK, Albano AM. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silverman WK, Ollendick TH. Evidence-Based Assessment of Anxiety and Its Disorders in Children and Adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34(3):380–411. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, Barrios V. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Versions. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;31(3):335–342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kendall PC, Compton SN, Walkup JT, et al. Clinical characteristics of anxiety disordered youth. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S-J, Kim B-N, Cho S-C, et al. The prevalence of specific phobia and associated co-morbid features in children and adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(6):629–634. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pauschardt J, Remschmidt H, Mattejat F. Assessing child and adolescent anxiety in psychiatric samples with the Child Behavior Checklist. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(5):461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petty CR, Rosenbaum JF, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, et al. The child behavior checklist broad-band scales predict subsequent psychopathology: A 5-year follow-up. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(3):532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multihealth Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finch AJ, Saylor CF, Edwards GL. Children’s Depression Inventory: Sex and grade norms for normal children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:424–425. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ollendick TH, Yule W. Depression in British and American children and its relation to anxiety and fear. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:126–129. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smucker MR, Craighead WE, Craighead LW, Green BJ. Normative reliability data for the Children’s Depression Inventory. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1986;14:25–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00917219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finch AJ, Saylor CF, Edwards GL, McIntosh JA. Children’s Depression Inventory: Reliability over repeated administrations. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;16:339–341. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kazdin AE. Children’s depression scale: Validation with child psychiatric inpatients. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1987;28:29–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1987.tb00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson WM, Politano PM. Children’s Depression Inventory: Stability over repeated administrations in psychiatric inpatient children. J Clin Child Psychol. 1990;19:254–256. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Comer JS, Kendall PC. High-End Specificity of The Children's Depression Inventory in a Sample of Anxiety-Disordered Youth. Depress Anxiety. 2005;22(1):11–19. doi: 10.1002/da.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merikangas KR, Ames M, Cui L, et al. The impact of comorbidity of mental and physical conditions on role disability in the US adult household population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1180–1188. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zweig MH, Campbell G. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) plots: A fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine. Clin Chem. 1993;39:561–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fava M, Hwang I, Rush A, Sampson N, Walters E, Kessler R. The importance of irritability as a symptom of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:856–867. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joiner T, Metalsky G, Gencoz F, Gencoz T. The relative specificity of excessive reassurance-seeking to depressive symptoms and diagnoses among clinical samples of adults and youth. J Psychopath Behav Assess. 2001;23:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kendall PC, Hedtke KA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious children: Therapist manual. Third Edition. Armore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piacentini J, Langley A, Roblek T. Cognitive behavioral treatment of childhood OCD: It’s only a false alarm. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pincus DB, Ehrenreich JT, Mattis SG. Mastery of anxiety and panic for adolescents: Riding the wave, therapist guide. New York, NY US: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rynn M, Puliafico A, Heleniak C, Rikhi P, Ghalib K, Vidair H. Advances in pharmacotherapy for pediatric anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:76–87. doi: 10.1002/da.20769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Compton SN, Walkup JT, Albano AM, et al. Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS): Rationale, design, and methods. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Mental Health. 2010;4 doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pine D, Costello E, Zeanah C, et al. The conceptual evolution of DSM-5. Arlington, VA US: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2011. Increasing the developmental focus in DSM-5: Broad issues and specific potential applications in anxiety; pp. 305–321. [Google Scholar]