Abstract

Objective

This study examined changes in the therapeutic alliance and in self-reported anxiety over the course of 16 weeks of manual-based family treatment for child anxiety disorders.

Method

86 children (51.3% female; aged 7.15 to 14.44; 86.2% Caucasian, 14.8% minority) with a principal diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and/or social phobia, and their parents, received family treatment for anxiety disorders in youth. Child, therapist, and parent ratings of therapeutic alliance and child ratings of state anxiety were measured each session. Latent difference score growth modeling investigated the interacting relationship.

Results

Therapeutic alliance change, as rated by the mother and by the therapist, was a significant predictor (medium effect) of latter change in child anxiety (with greater therapeutic alliance leading to later reduction in anxiety). However, changes in child-reported anxiety also predicted latter change in father- and therapist-reported alliance (small-to-medium effect). Prospective relationships between child-reported therapeutic alliance and child-reported symptom improvement were not significant.

Conclusions

Results provide partial support for a reciprocal model in which therapeutic alliance improves outcome, and anxiety reduction improves therapeutic alliance.

Keywords: Alliance, child anxiety, family treatment, process

Studies have reported that therapeutic alliance components can be predictive of a favorable treatment outcome in adults and youth across various treatment modalities (see Horvath & Symonds, 1991; Martin, Garske, & Davis, 2000; McLeod, 2011; Shirk, Karver, & Brown, 2011). In child therapy, current conceptualizations of therapeutic alliance find that a unidimensional model of therapeutic alliance—one that incorporates the affective bond and agreement/collaboration on tasks and goals—is developmentally applicable and supported by data (DiGiuseppe, Linscott, & Jilton, 1996; Faw, Hogue, Johnson, Diamond, & Liddle, 2005). Therapeutic alliance, as such defined, is viewed as a process that evolves across a course of treatment (e.g., Kendall et al., 2009). Across treatments for child disorders, therapeutic alliance has been found to be a modest predictor of treatment outcome (McLeod, 2011; Shirk et al., 2011), but at present the role of therapeutic alliance in symptom reduction within the treatment of child anxiety disorders specifically remains poorly understood.

A strong therapeutic alliance may be particularly important for successful treatment with youth (Chu et al., 2004; Elvins & Green, 2008; Kazdin, Witley, & Marciano, 2006; Shirk, Karver, and Brown, 2011). Therapy for youth is typically not self-sought, and many interventions are either advised or mandated by others. Children are often referred by a school, agency, court, or other social service provider for treatment of problems that they do not believe they have. A favorable therapeutic alliance may be needed to complete therapy tasks, such as the exposure tasks that have been deemed critical to improvement (Beutler & Harwood 2002; Kazdin & Weisz, 1998; Kendall et al., 2009). By definition, exposure tasks are distressing to the client and therefore trust and confidence in the therapist can be vital. That is, a strong therapeutic alliance—characterized by agreement/collaboration on tasks and goals in the context of a strong affective bond—may be essential to the child's ability and willingness to confront fears and eventually overcome them (Kendall, Chu, Gifford, Hayes, & Nauta, 1998; Ollendick & King, 1998). Therapeutic alliance has been linked to family treatment involvement and retention (Hawley & Weisz, 2005), increased treatment acceptability, and lower perceived barriers to care (Kazdin et al., 2005).

Regarding therapy for youth, an initial meta-analysis (Shirk & Karver, 2003) found an overall effect size of r = 0.21 between treatment outcome and the therapeutic relationship, which was roughly comparable to the pooled effect size reported in Martin, Garske, and Davis’ (2000) meta-analysis examining therapeutic alliance and outcome within the broad population of clients across the lifespan. Such effects are significant but small, as they explain only a modest portion of the outcome variance. Although this initial meta-analytic evidence supported the therapeutic relationship as a predictor of child symptom improvement, limitations precluded causal inferences. Most of the included studies employed cross sectional analyses, whereby treatment responders typically reported stronger therapeutic relationships than non-responders at post treatment. Moreover, most of the included studies did not examine therapeutic alliance per se, but rather the overall therapeutic relationship.

Recent empirical work has more consistently employed longitudinal designs in the study of therapeutic alliance and outcomes in child therapy (e.g., Chiu et al., 2009; Liber et al., 2010; McLeod & Weisz, 2005). McLeod (2011) recently meta-analyzed the relevant child therapy literature, which had grown by roughly 65% since the initial Shirk and Karver (2003) meta-analysis. Although most studies in Shirk and Karver examined the therapeutic relationship in general, rather than therapeutic alliance per se, McLeod’s more recent meta-analysis examined 38 studies investigating the link between therapeutic alliance and outcome across various modes of child therapy (e.g., individual, family, parent, multisystemic). McLeod found a small overall weighted association between therapeutic alliance and outcome (r = 0.14). Meta-analytic findings based solely on prospective studies that measured therapeutic alliance prior to outcome within the context of individual child therapy indicate a higher weighted effect size (r = 0.22), particularly for behavioral interventions (Shirk, Karver, & Brown, 2011).

To date, much of the prospective child therapy research on therapeutic alliance and outcome has relied on two-wave or three-wave approaches to longitudinal data (e.g., early vs. later session data; pre- vs. mid- vs. post-treatment data). Such work does not afford rich examination of trajectories across treatment, and the dynamic interplay between therapeutic alliance and outcome across time. Moreover, research has not ruled out reverse causation (see Crits-Cristoph, Gibbons, Hamilton, Ring-Kurtz, & Gallop, 2011), in which therapeutic alliance is simply a marker for improvements to-date (i.e., earlier symptom reductions, rather than therapeutic alliance, lead to subsequent symptom reductions). In the case of childhood anxiety, it is possible that treatment response (i.e., child anxiety reductions), in turn, leads to more favorable therapeutic alliance. The present study evaluates both timing effects and reverse causality in the examination of therapeutic alliance and anxiety measured each week across the course of therapy.

Regarding therapeutic alliance and anxiety, does one bring about change in the other? Many suggest that a strong therapeutic alliance can promote symptom response in the treatment of childhood anxiety (e.g., Chu et al., 2004), although research has yet to evaluate therapeutic alliance-outcome relationships with multiple perspectives reporting on therapeutic alliance. Initial reports suggested no relationship between therapeutic alliance and anxiety in the context of individual child therapy (Kendall, 1994; Kendall et al., 1997), although these studies used child-reported therapeutic alliance, measured at posttreatment rather than prospectively, which offered only a truncated range (mostly high) of therapeutic alliance ratings (see also Chu et al., 2004). In addition, recent analyses incorporating observational therapeutic alliance data have produced mixed findings. Chiu, McLeod, Har and Wood (2009) found that early therapeutic alliance predicted mid-treatment anxiety response, but not post-treatment anxiety response, and improvements in therapeutic alliance across the course of treatment predicted better post-treatment outcomes. In contrast, Liber and colleagues (2010) found minimal association between early therapeutic alliance and treatment response.

A challenge in this area is how to evaluate hypotheses regarding the dynamic interaction of therapeutic alliance and symptoms across therapy. Two-wave (i.e., early versus later) data analyses are insufficient to address such transactional relationships. One method for examining these processes over time is the latent difference score model (McArdle, 2001, 2009; McArdle & Hamagami, 2001), which affords examination of how one variable affects later change in another variable and vice-versa. Thus, we can determine the influence of therapeutic alliance on later change in anxiety and anxiety’s influence on later therapeutic alliance change.

The present study tested whether the therapeutic alliance—unidimensionally characterized by agreement/collaboration on tasks and goals in the context of a strong affective bond—predicts subsequent anxiety reduction, as well as whether anxiety reduction predicts subsequently improved therapeutic alliance, in a family-based treatment for childhood anxiety disorders. As Kazdin and Nock (2003) noted, such work involves using a repeated measures design to assess process and symptom variables at multiple time points throughout therapy to demonstrate both an association between therapeutic alliance and symptom change, and temporal precedence (e.g., that therapeutic alliance/anxiety change predicts subsequent anxiety/alliance change). Traditional two-wave (e.g., pre- vs. post-treatment) approaches are limited in the extent to which they can evaluate the shape of therapeutic alliance growth across treatment and assess nonlinear trajectories. Consistent with Barber, Connolly, Crits-Christoph, Gladis and Siquel and (2000), we evaluated changes within a treatment, rather than comparing across treatments (see Teachman, Marker, & Smith-Janick, 2008; Teachman, Marker, & Clerkin, 2010). Self-reported anxiety was assessed prior to each session, and therapeutic alliance was assessed following each session. This method permitted us to model the change trajectories for anxiety and therapeutic alliance, and then use structural equation modeling (SEM) to test whether change in therapeutic alliance predicted later changes in anxiety, and/or whether change in anxiety predicted later change in therapeutic alliance. Given previous literature, it was hypothesized that therapeutic alliance would predict later improvement in symptoms. We also expected a reciprocal relationship whereby improvement in anxiety symptoms preceded growth in therapeutic alliance.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 86 youths (51.3% female) whose ages ranged between 7.15 and 14.44 (M=10.19, SD=1.7), and their parents. They were referred to and obtained treatment from the Child and Adolescent Anxiety Disorders Clinic (CAADC) as part of a larger randomized clinical trial (RCT; Kendall et al, 2008). Children’s race/ethnicity was: 86.2% Caucasian, 7.2% African American, and 6.6% classified as Other. The yearly household income was as follows: 8.6% of the families earned less than $29,999; 22.4% earned between $30,000 and $59,999; and the other 61.8% earned $60,000 or greater. All of the referred youth met criteria for a diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and/or social phobia (SP) based on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children and Parents for DSM–IV (ADIS C/P; Silverman & Albano, 1996). Exclusionary criteria included (a) an IQ of below 80, (b) psychotic symptoms present during intake, or (c) prescription of antidepressant or anti-anxiety medication. Sixty-seven children lived with both their mother and their father, and 83 mothers and 54 fathers participated in the present study. In several cases, only one parent in two-parent families was available. Therapeutic alliance data from 5 children were not available, so these children were not included.

Measures

Diagnostic status

The ADIS-C/P (Silverman & Albano, 1996) is a semi-structured diagnostic interview that assesses child psychopathology according to DSM–IV criteria. The ADIS-C (child version) and the ADIS-P (parent version) were used to collect data on the child’s and parents’ reports of the child’s anxiety. Silverman and Ollendick (2005) noted that the ADIS-C/P is reliable, valid, and sensitive to change. The anxiety disorders section of the ADIS-C/P for DSM–IV has demonstrated strong concurrent validity (Wood, Piacentini, Bergman, McCracken, & Barrios, 2002). In age ranges comparable with those of the present sample, the interview has demonstrated good reliability for parent (ranging from .65 to .88) and child (ranging from .63 to .88) diagnostic profiles (Silverman & Ollendick, 2005; Silverman, Saavedra, & Pina, 2001).

Therapeutic alliance

The child’s perception of the therapeutic alliance was measured using a revised Therapeutic Alliance Scale for Children (TASC; Shirk & Saiz, 1992; adapted to assess the therapeutic alliance at each session). Items are consistent with original TASC items, with the exception that the time frame referred to “in the past week.” The revised Child TASC (TASC-r) is a 12-item scale completed by the child (e.g., “I liked spending time with my therapist,” “I felt like my therapist was on my side and tried to help me”). Items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Although initial TASC reports supported the use of three therapeutic alliance subscales (i.e., positive bond, negativity, task collaboration; Shirk & Saiz, 1992), recent applications and conceptualizations in child therapy find a unidimensional model of therapeutic alliance (which combines these three components) as more developmentally applicable and supported (DiGiuseppe, Linscott, & Jilton, 1996; Faw, Hogue, Johnson, Diamond, & Liddle, 2005). The items in the revised weekly TASC were summed for the present purposes (see also Kendall et al., 2009 and Creed & Kendall, 2005 for similar applications of the TASC-r). Children were informed that their ratings would be confidential and that their therapist would not see their responses. The child completed the TASC-r separate from the therapist at the conclusion of each session and deposited it in a sealed box.

In a sample of anxiety-disordered youths, the Child TASC-r total scores had high internal consistency at each session (child α from .88 to .92; therapist from .94 to .96; Creed & Kendall, 2005), supporting its use as a unidimensional measure. In the present study, alpha coefficients were very high across sessions for child-report and for therapist-report (α from .83 to .91, Mean α = .87). The quality of the therapeutic alliance is expected to fluctuate over time (Safran, 1993; Safran & Muran, 2006), and so retest reliability of the TASC reflects both true therapeutic alliance change and the measure’s consistency (14 day test-retest = .65 for children and .82 for therapist; Harrison, 2007). The goal then is to find a measure that is reliable, but also measures change over time. The therapist’s perception of the child-therapist alliance was measured with a therapist version of the TASC. The 12-question Therapist TASC-r has items parallel in content to those on the Child TASC-r. Parent perception of the child-therapist alliance was measured with a parent version of the TASC. The Parent TASC-r assessed the parent view of the child-therapist alliance at each session. Internal consistency of these parent-reports of the child-therapist alliance was strong in the present sample (αMother from .68 to .82, Mean αMother = .75; αFather from .72 to .89, Mean αFather = .83).

State Anxiety

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC; Spielberger, 1973). The STAIC is comprised of separate, self-report scales for measuring state anxiety (State form) and trait anxiety (Trait form). The STAIC is similar in conception and structure to the adult State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970) and is commonly used in treatment studies. In the original normative sample, the alpha coefficients for the STAIC was 0.82 for males and 0.87 for females. This study focused on child state anxiety (STAIC State form), which has a 6 month test-retest reliability of .47, suggesting that an adequate amount of change can be measured (Beidel, Fink, & Turner, 1996). For the present purposes, we administered an adapted version of the STAIC (State form) at the beginning of each session, with instructions for the child to report on their experience of anxiety during the past week. The time frame of these instructions differs from the original STAIC (State form), which has individuals report on their experiences in the moment. Applying a 1-week time frame for the State form of the STAI has been used successfully in previous research examining transient anxiety symptoms in youth (e.g., Biegel et al., 2009). In the present sample, internal consistency for this adapted STAIC (State form) was high (α from .65 to .97, Mean α = .89).

Procedures

Study procedures were conducted under approval of the Temple University IRB. Children were referred to the CAADC by parents, school personnel, and mental health professionals for anxiety treatment. Parents completed procedures of informed consent, and children provided assent. At intake, participants were administered the ADIS-C/P. For each child, separate diagnosticians conducted the parent and child ADIS interviews. Diagnosticians each conducted an approximately equal number of parent and child interviews to control for potential bias. Evaluation of agreement among diagnosticians revealed high inter-rater reliability (k = .80). Following the interview, each diagnostician independently assigned diagnoses (for details, see Silverman & Albano, 1996), resulting in three diagnostic profiles for each child: (a) child self-report diagnoses, (b) parent-report child diagnoses, and (c) composite child diagnoses (generated by integrating the independent diagnostic profiles using the “or” rule; see Comer & Kendall, 2004; Silverman & Albano, 1996). Using composite diagnoses, three overlapping groups were identified: children meeting criteria for SAD, for SP, and for GAD. As is typical (Verduin & Kendall, 2003), comorbidity among the anxiety disorders was high, with 60% of the participating youths meeting criteria for more than one of the three diagnoses. Thirty percent met criteria for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 14% met for oppositional defiant disorder, 10% percent met for major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder, and 1% met for conduct disorder.

All children from a larger RCT (Kendall et al., 2008) who participated in family treatment for child anxiety were included in the present study. Included children received either a manual-based family cognitive-behavioral treatment (FCBT; n = 47) or a manual-based family education, support, and attention condition (FESA; n = 39). Each treatment consisted of 16 sessions lasting 60 minutes per session, with an average of one session per week. Both treatments (1) focused attention on the child’s problems in a family context, (2) educated families about anxiety and emotions, (3) provided experience with an understanding and caring therapist, and (4) assigned homework. FESA participants learned about emotions and anxiety, and theories to explain anxiety (e.g., cognitive, behavioral, biological) were also offered. However, FESA participants did not receive CBT (e.g., no exposure tasks). Previous work has shown that the shape of therapeutic alliance growth across time did not differ across these two treatment groups (Kendall et al., 2009).

Treatment protocols were implemented by master’s-level therapists with 2–3 years of experience and doctoral-level psychologists (n = 16), with supervision by licensed doctoral-level psychologists with 6–7 years of experience in the community. All therapists for each condition studied written materials (manuals) and participated in training (typically two 3-hour workshops) before initiating supervised pilot experience. Workshops included didactic presentation, role-plays, trainee demonstration, videotape playback, and discussion. Following training, and continuing throughout, all therapists participated in weekly 2-hour supervision groups.

A CAADC staff member, other than the therapist, had the child and parent complete the TASC-r forms at the end of each session and then fold and insert the form in a sealed box. Therapists independently completed the TASC-r at the end of each session. Therapists, children, and parents were blind to all TASC-r ratings and study hypotheses. Details regarding the design of the larger RCT are provided elsewhere (Kendall et al., 2008).

Results

Descriptive statistics are listed in Table 1. Specifically, means and standard deviations are noted for the main assessment points for therapeutic alliance and state anxiety. The therapist providing treatment was not significantly associated with either the trajectory of anxiety symptoms (p = .58) nor the trajectory of the four therapeutic alliance outcomes (ps ranged from .17 to .96).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics (means with SD in parentheses) for the measures of anxiety and alliance.

| Treatment Session |

STAIC | Therapist’s Rating of Alliance |

Child’s Rating of Alliance |

Mother’s Rating of Alliance |

Father’s Rating of Alliance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32.77 (7.23) | 33.48 (7.64) | 38.86 (7.19) | 42.13 (3.82) | 41.35 (4.83) |

| 2 | 30.29 (6.62) | 35.64 (7.56) | 39.27 (8.51) | 42.86 (5.94) | 41.76 (5.72) |

| 3 | 30.25 (6.70) | 35.26 (8.03) | 40.80 (7.45) | 44.12 (4.64) | 43.33 (4.45) |

| 4 | 30.10 (7.30) | 36.50 (7.79) | 41.80 (6.36) | 44.91 (3.36) | 42.70 (6.18) |

| 5 | 30.06 (7.00) | 37.23 (7.78) | 41.33 (6.73) | 45.17 (3.39) | 42.64 (6.58) |

| 6 | 30.16 (7.43) | 36.15 (7.99) | 41.15 (6.88) | 44.96 (4.24) | 42.68 (6.59) |

| 7 | 30.00 (7.03) | 36.75 (8.13) | 41.65 (6.57) | 45.19 (4.07) | 43.45 (5.62) |

| 8 | 29.93 (7.64) | 36.76 (7.79) | 41.59 (7.41) | 45.63 (2.95) | 44.59 (4.10) |

| 9 | 30.06 (7.74) | 37.14 (8.46) | 41.41 (7.73) | 45.83 (2.97) | 43.84 (5.74) |

| 10 | 28.89 (7.19) | 36.15 (8.56) | 41.65 (6.71) | 45.22 (3.92) | 44.25 (3.86) |

| 11 | 28.25 (6.84) | 36.64 (8.50) | 41.43 (7.18) | 45.67 (3.11) | 43.98 (5.23) |

| 12 | 29.52 (7.79) | 36.90 (8.37) | 41.29 (7.49) | 45.58 (4.10) | 43.30 (5.54) |

| 13 | 28.97 (6.92) | 36.33 (8.30) | 41.11 (8.27) | 45.94 (3.43) | 43.58 (4.88) |

| 14 | 28.74 (6.83) | 36.76 (8.11) | 41.98 (7.25) | 45.75 (3.31) | 43.26 (4.86) |

| 15 | 28.95 (6.74) | 36.88 (8.62) | 40.95 (8.30) | 45.96 (3.77) | 43.80 (4.50) |

| 16 | 29.48 (7.06) | 38.88 (8.82) | 42.41 (7.90) | 45.61 (5.09) | 44.10 (4.90) |

Note. STAIC = State Anxiety Inventory for Children (State form)

A series of bivariate latent difference score (LDS) models evaluated how therapeutic alliance and anxiety interacted across the course of treatment. These models were used to examine whether one variable was a leading indicator of change in the other variable. Due to space limitations, a complete description of LDS models is not possible. Interested readers are referred to McArdle and Nesselroade (2002), McArdle (1988), and McArdle & Hamagami (2001). Readers interested in practical examples are referred to Hawley, Ho, Zuroff, and Blatt (2006; 2007), Teachman, Marker, and Smith-Janick (2008), and Teachman, Marker, and Clerkin (2010); for a review of LDS, see Ferrer and McArdle (2010). The LDS model is an alternative method for the structural modeling of longitudinal data that integrates features of latent growth curve models and cross-lagged regression models. LDS fits for examining the present questions because one can simultaneously model overall change across time and lagged relationships, allowing an estimate of whether change in therapeutic alliance predicts later change in anxiety symptoms, while controlling for overall change in both.

Prior to fitting the bivariate LDS models, univariate LDS models were tested to determine the best fitting pattern of change. The latent difference score models allow for many different models of change with different possible components: (a) an additive component, which represents a linear change; and (b) a proportional change component that allows nonlinear patterns to dampen or strengthen the linear slope. LDS models are typically specified as linear models. However, the accumulation of proportional change can result in distinct nonlinear trajectories. This result may be because, at each time, both the self-feedback and coupling parameters are multiplied by scores at the previous state, which can change over time. Thus, although the coefficients themselves can remain constant across all occasions, they are multiplied by changing values, resulting in effects that compound over time and fit a wide variety of trajectory patterns. The best fit for each variable was determined using a chi square difference test. Generally, the linear model provided the best fit of the data. In cases where the nonlinear model provided the best fit, the linear model had a similar enough fit to justify using the linear model across in the bivariate models. The linear model also has an added benefit in that it provides a parsimonious description of change. Both therapeutic alliance and anxiety changed across the course of treatment and provided justification to continue to the next step. Furthermore, correlations of the univariate models indicated that slopes of both variables were significantly correlated. Thus, it seems the change processes were related and the positive correlation provided justification to evaluate which variable was a leading indicator.1

The separate univariate latent models were then combined to create the bivariate latent difference score models2. The change process could go in either direction as therapeutic alliance could predict subsequent change in anxiety, or vice versa. We simultaneously estimated a parameter that predicted later change in the other variable (i.e., therapeutic alliance change as the predictor of change in anxiety and anxiety change as the predictor of change in therapeutic alliance). That is, we wanted to determine whether change was significant in either direction.

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) estimation was used for all analyses with Mplus software (Muthén & Muthén, 2010; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010). MCMC is a type of Bayesian estimation, which uses prior distributions on all parameters and simulation-based estimation is especially suited for small sample sizes and incomplete data. Furthermore, all models were also estimated with full information maximum likelihood estimation (Muthén & Muthén, 2008) and results were similar. These procedures estimate the model parameters using all available information rather than deleting cases with incomplete data (Enders, 2001). Thus, people who did not have all sessions completed were still used in the analyses. This decision was made to maximize power and to be conservative in our approach (by not only examining treatment completers). To help address the potential impact of attrition on the results, we conducted an analysis of incomplete data (see Little & Rubin, 2002). As part of this analysis, we examined variables that might predict patterns of missingness with new procedures in Mplus (based on Collins, Schafer, & Kam, 2001; Enders, 2010; Graham, 2003). Initial levels of therapeutic alliance and anxiety were not found to be significant predictors of incomplete data. Thus, we can assume that any pattern of missingness is missing at random.

Model 1: Therapist rating of therapeutic alliance and experience of anxiety

Model 1 examines whether therapeutic alliance change leads to later change in anxiety symptoms and/or whether symptom change leads to later change in therapeutic alliance.

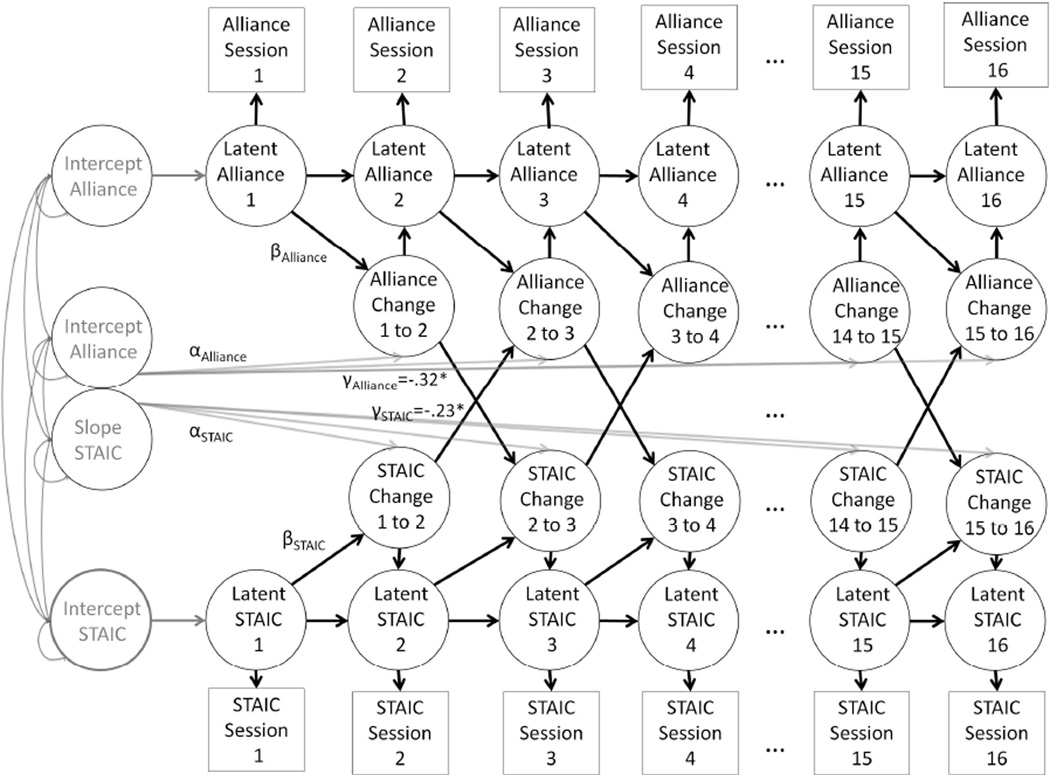

Figure 1 presents a diagram showing this relationship with the bivariate latent difference score model. This figure presents therapeutic alliance and anxiety measured at 16 occasions. At each occasion, a latent variable representing change in the true scores for each variable from the previous occasion is created (i.e., labeled STAIC change; Alliance change). Most arrows have parameters that are set to one (approach modeled from McArdle & Nesselroade, 2002), whereas the arrows labeled with the α (alpha) parameters are used to estimate the change in each variable over time. The β (beta) parameters are used to model proportional change. For the present purposes, the arrows from the change in one variable to the later change in the other variable are the most important. They represent relationships between variables (i.e., whether one variable predicts later change in the other variable). The α and γ parameters are constrained to be equal across time (i.e., we constrain the change process to be the same over time). In sum, the analysis addressed the specific question of whether one change process was a leading indicator of the other change process. As hypothesized, change in therapist-rated therapeutic alliance predicted later change in child anxiety (γalliance = −0.32; 95% C.I. = −0.12, – 0.48; p < .05; standardized coefficients). That is, the greater the therapeutic alliance improvement as reported by the therapist, the more reduction in symptoms seen later in therapy. Additionally, reduction in anxiety symptoms predicted later change in therapeutic alliance (γSTAIC = −0.23; 95% C.I. = −0.03, −0.44; p < .05). The amount of anxiety reduction predicted how much therapeutic alliance would be seen later in therapy.

Figure 1.

Bivariate latent difference score model of the State Anxiety Scale for Children (STAIC) and Therapist Alliance Scale for Children (TASC-R). Previous score on alliance is a significant predictor of later change on the anxiety. Additionally, previous score on anxiety is a significant predictor of later change on alliance.

Note. The role of the latent intercepts and slopes is to describe change in a manner similar to a latent growth curve model (i.e., to take into account the starting point and overall linear change process for each measure separately, as we look at our primary question of how the change processes across variables are predictive of one another). The α refers to alpha (estimate to model straight-line growth) and the β refers beta, which is a proportional change (allowing the trajectory to have a non-linear slope).

Model 2: Child rating of therapeutic alliance and experience of anxiety

A similar model to the above model was run with the child’s rating of therapeutic alliance change predicting change in anxiety symptoms (and vice versa). Change in the child-rated therapeutic alliance did not predict later change in anxiety symptoms (γalliance = −0.05; 95% C.I. = 0.08, - 0.18; p > .05). Reduction in anxiety symptoms did not predict later change in child-rated therapeutic alliance (γSTAIC = −0.09; 95% C.I. = 0.04, −0.22; p > .05).

Model 3: Mothers’ rating of therapeutic alliance and child anxiety

Additional models investigated mothers’ report of therapeutic alliance change predicting change in anxiety symptoms (and vice versa). Mother-reported therapeutic alliance change predicted later change in anxiety (γalliance = −0.28; 95% C.I. = -0.07, – 0.47; p < .05). This medium effect indicates that the steeper the growth of mother-perceived child-therapist alliance predicted anxiety reduction later in therapy. Reduction in child anxiety did not predict later change in mother-rated therapeutic alliance (γSTAIC = −0.19; 95% C.I. = −0.03, −0.40; p > .05).

Model 4: Fathers’ rating of therapeutic alliance and experience of anxiety

A model investigated fathers’ report of alliance predicting child anxiety reduction (and vice versa). Change in father-rated alliance did not predict later change in child anxiety (γalliance = −0.18; 95% C.I. = 0.02, – 0.38; p > .05). The amount of child anxiety change significantly predicted later change in father-rated therapeutic alliance (γSTAIC = −0.21; 95% C.I. = −0.01, −0.42; p < .05). This medium effect was in the hypothesized direction with lower anxiety predicting greater therapeutic alliance change.

Discussion

It has been suggested that a strong therapeutic alliance, characterized by a high affective bond and collaboration and agreement on therapeutic tasks and goals, has a significant role in the successful treatment of youth (e.g., Elvins & Green, 2008; Kazdin, Whitley, Marciano, 2006; McLeod, 2011). The present findings regarding family-based treatment of child anxiety are consistent with previous findings documenting a role for therapeutic alliance in prospectively predicting treatment response in child therapy (see Shirk, Karver, & Brown, 2011). However, to our knowledge this is the first empirical study to show evidence of a reciprocal relationship between therapeutic alliance and treatment response across treatment, whereby reduction in anxiety symptoms led to improved therapeutic alliance, and vice versa, according to multiple reporters. Specifically, therapist- and mother-rated therapeutic alliance showed a medium effect when prospectively predicting anxiety symptom reduction. At the same time, anxiety reduction had a small to medium effect when predicting later child-therapist alliance (as rated by therapist and by father). The present longitudinal design, with measurements at each session, improves upon previous two-wave designs, and permits examination of the timing and shape of therapeutic alliance and anxiety changes rather than affording just a simple correlation between the two.

Regarding the treatment of child anxiety, this is the first study to examine alliance-outcome relationships with multiple perspectives reporting on therapeutic alliance. Prior research used child report (and was characterized by a ceiling effect in child-rated therapeutic alliance) and did not support a relationship between child-perceived therapeutic alliance and outcome (e.g., Kendall, 1994; Kendall et al., 1997). Consistent with these previous findings, the present study found that child-perceived therapeutic alliance was unrelated to outcomes in the context of family treatment of child anxiety disorders. In the present study, child-perceived therapeutic alliance showed wider variability (i.e., standard deviations) than parent-perceived therapeutic alliance, and comparable variability to therapist-perceived therapeutic alliance (see Table 1). In addition, mean child-perceived therapeutic alliance ratings were lower than mean parent-perceived therapeutic alliance ratings which did show associations with symptom response. Collectively, these findings suggest that the absence of associations between child-reported alliance and symptom response was not simply due to a restricted range or ceiling effect for child-reported therapeutic alliance data.

In contrast, we found therapist- and mother-perceived child-therapist alliance were significant prospective predictors of subsequent improvements in child-reported anxiety. The strengths of these prospective associations were stronger than the alliance-outcome relationships identified in the prospective observational work of Liber, McLeod, Van Widenfelt et al. (2010) and Chiu, McLeod, Har and Wood (2009), the latter of which found that early therapeutic alliance predicted mid-treatment, but not post-treatment, anxiety response. The stronger relationships presently found may reflect important differences between treatment formats in alliance-outcome relationships (only 18 of 34 children in Chiu et al. received family-based treatment; all children in Liber et al. received either individual or group-based treatment), or may reflect key differences in what is assessed by self-report versus observational data collection methods. Meaningful therapeutic alliance elements related to outcome may be captured in mother- and therapist-perspective reports that are not captured by observational strategies. Similarly, it is possible that parent- and therapist-reports are subject to biases that do not affect observational data. Future work incorporating both observational and multiple-perspective reports of therapeutic alliance is needed in this area.

The prospective relationships between symptom change and subsequent therapeutic alliance change in the treatment of child anxiety have been understudied. In a rare exception, Chiu and colleagues (2009) did not find a reciprocal relationship with reduction of anxiety predicting later improvement in therapeutic alliance. In contrast, the present analyses found symptom improvement significantly predicted improvements in therapist- and father-perceived therapeutic alliance. Again, differences in the proportion of family-based treatment cases studied, or methodology differences in the measurement of therapeutic alliance, may explain the inconsistent results. In addition, differences in data analytic approaches may explain the discrepant findings. The latent difference score modeling conducted in the present report allows for the simultaneous modeling of change in one process influencing change in the other, whereas the use of multiple regression of change scores does not.

McArdle (2010) called for developmental researchers to model the dynamic processes that unfold over time. Similarly, treatment outcome researchers need to consider the way trajectories change over time, as well as critical factors in the change process. As Nesselroade (1991, 2000) described, it is important to model both the process in the individual, as well as the average effect of everyone. The modeling used in this report describes how an individual’s change process in therapeutic alliance affects his or her change in anxiety (and vice versa). The effects from the individuals are then aggregated to determine an average effect across individuals.

An advantage of the current study is the multiple reports of child-therapist alliance, although this method has been understudied. Although studies evaluating therapeutic alliance in family treatments have increasingly incorporated parent-therapist alliance measurements (e.g., Kazdin et al., 2006; Hawley & Weisz, 2005), measurement of parents’ perceptions of the child-therapist alliance remains rare. Parent perceptions of the child–therapist alliance can be important for optimizing treatment retention, and fostering engagement in treatment-related tasks in session and at home. Parents who perceive their child is not bonding or collaborating with their therapist may be less inclined to continue bringing their child to sessions or engage children out of session in treatment-related tasks.

Parent-child reporting discrepancies have been noted previously in the treatment of child anxiety disorders (e.g., Comer & Kendall, 2004). Although therapist and parent perceptions of the child-therapist alliance showed associations with changes in children’s reports of anxiety across treatment, the present analyses did not support an association between children’s perceptions of therapeutic alliance and treatment response in the family-based treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. This finding is consistent with previous work examining child perspectives of therapeutic alliance in the context of individual treatment of child anxiety (e.g., Kendall, 1994).

Although the present study addressed issues of temporal precedence (i.e., whether anxiety symptoms or therapeutic alliance changes first or whether either process is a leading indicator of change in the other), the study is not without limitations. The use of a single child-report measure to capture weekly anxiety change across treatment may be limited. Future work in this area may do well to complement child-reports of symptom change with weekly data drawn from parent-report, observational, and physiological measurements. In addition, it is not clear how the mid-to-high retest correlations associated with the TASC-r might have influenced the present findings. The quality of the therapeutic alliance is expected to evolve over time (Safran, 1993; Safran & Muran, 2006). Retest reliability of measures of constructs expected to evolve across time (e.g., therapeutic alliance) reflects both true change and the measure’s consistency. Without a multimodal evaluation of therapeutic alliance, the full extent to which therapeutic alliance change reflects true change versus measure inconsistency remains unclear. Moreover, given the number of therapists participating in the study, the sample size, and the relatively small number of cases treated per therapist, when we accounted for therapist differences in the analyses, the models did not converge. Future work with larger sample sizes and increased caseloads per therapist is needed to evaluate the relationships between therapeutic alliance and outcome after accounting for individual therapist effects. Finally, to fully investigate the causal mechanism of change, alternative explanations or ’third variables’ would need to be ruled out. Alternative explanations include but are by no means limited to (1) gender and cultural differences between client and therapist, and (2) readiness of client to change (not measured). Gender and ethnic differences were examined with no differences found. However, sample size limitations may have affected the power with which to find true differences.

Differences between the client and therapist can influence therapeutic alliance. For adults, a client-therapist mismatch in gender, race, and ethnicity, amongst other cultural differences may affect therapeutic alliance (e.g., Maramba, & Nagayama Hall, 2002; Sue, Fujino, Hu, Takeuchi, & Zane, 1991; Zane, Sue, Chang, Huang, Huang, Lowe, Srinivasan, et al., 2005). Such differences, not examined in the present work, require future attention.

A client’s (child’s) motivation to change may also need to be considered in future work examining the relationships between therapeutic alliance and anxiety reduction. As noted, youth are brought to treatment by parents or school officials and, not surprisingly, their motivational balance may be tipped against change. Chu and Kendall (2004) indicated that positive treatment outcome was related to how much a child was involved in therapy. Future work is needed in this area to evaluate child motivation for change in the context of therapeutic alliance and symptom improvements. The stages of change model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1992), includes pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Motivation and an adult client’s readiness to change have been identified as contributing to treatment outcome (Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003; Riemsma et al., 2002; Rubak, Sandbaek, Lauritzen, & Christensen, 2005).

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Despite emerging literature on the modest, but significant, role of therapeutic alliance in contributing to engagement in therapeutic tasks and symptom improvement, rigorous investigations evaluating the prospective relationships between therapeutic alliance and symptom improvements across time are limited. Given the importance practitioners often attribute to therapeutic alliance in determining outcome, this latter issue is critical to informing dissemination efforts of evidence-based practices. In a survey of 1,179 child mental health practitioners, Kazdin, Siegel, and Bass (1990) found over 90% of practitioners rated the relationship between the therapist and the child as “very much” or “extremely” related to change. In contrast, only 50% reported specific therapeutic techniques as related to change. Similarly, Boisvert and Faust (2006) found mental health practitioners provided a mean rating of 5.38 on a scale of 1–7 (7=full agreement), indicating the extent of their endorsement of the statement “The relationship between the therapist and client is the best predictor of treatment outcome.” In the present analysis, we found partial support for a prospective relationship between child-therapist alliance and child-reported symptom change, when therapeutic alliance was rated by therapists or by mothers. At the same time a prospective relationship was found between child-reported symptom change and child-therapist alliance, when therapeutic alliance was rated by therapists or fathers. Taken together, these findings suggest a dynamic interplay between symptom improvement and therapeutic alliance, and may be used to inform efforts to improve the uptake of evidence-based practices in community settings.

Specifically, given that the extent to which mental health practitioners are willing to adopt empirically supported treatments may be contingent on their beliefs about the impact that supported techniques may have on therapeutic alliance, it may be of value for dissemination efforts to emphasize for practitioners that supported techniques for improving symptoms may in turn improve therapeutic alliance.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clinical interviewers, therapists, and research assistants at the CAADC, as well as Matthew Carper and Jeremy Peterman for their assistance with the data. This research was supported by NIMH research grants MH64484 and MH63747 awarded to Philip C. Kendall and MH090247 awarded to Jonathan S. Comer.

Footnotes

A more complete discussion of these preliminary steps can be found in an appendix on the first author’s webpage.

The study included data from two different types of treatment, FCBT and FESA. Initially, a multigroup analysis was completed, in which the two treatment groups were allowed to vary in each of the bidirectional effects, but no significant differences between the groups were found, and overall the parameters were very similar. At baseline we did not see any significant differences in the groups in alliance measures nor the STAIC. Previous work (Kendall, Comer et al., 2009) on the same sample found no between-group differences in the alliance trajectories across treatment. Distribution of variables and analysis of missingness was also completed. We utilized estimation procedures that can handle deviations from normal distributions and missingness. Thus, we combined both treatments as to estimate the most reliable parameters of bidirectional effects.

References

- Ackerman S, Hilsenroth M. A review of therapist characteristics and techniques positively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23(1):1–33. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albano AM, Silverman WK. Clinical manual for the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Child Version. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Bayesian analysis of latent variable models using Mplus. Technical Report. 2010 Retrieved from http://statmodel.com/papers.shtml.

- Barber JP, Connolly MB, Crits-Christoph P, Gladis L, Siqueland L. Alliance predicts patients’ outcome beyond in-treatment change in symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:1027–1032. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, Wampold BE, Imel ZE. Untangling the alliance-outcome correlation: Exploring the relative importance of therapist and patient variability in the alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(6):842–852. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LE, Harwood TM. What is and can be attributed to the therapeutic relationship? Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2002;32(1):25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Beidel DC, Fink CM, Turner SM. Stability of anxious symptomatology in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24(3):257–269. doi: 10.1007/BF01441631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegel GM, Brown KW, Shapiro SL, Schubert CM. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:855–866. doi: 10.1037/a0016241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert CM, Faust D. Practicing psychologists’ knowledge of general psychotherapy research findings: Implications for science-practice relations. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2006;37:708–716. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London: Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(5):843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu AW, McLeod BD, Har K, Wood JJ. Child-therapist alliance and clinical outcomes in cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(6):751–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu B, Choudhury M, Short A, Pincus D, Creed T, Kendall P. Alliance, technology, and outcome in the treatment of anxious youth. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2004;11(1):44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chu B, Kendall PC. Positive association of child involvement and treatment outcome within a manual-based cognitive-behavioral treatment for children with anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:821–829. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam C. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:330–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Kendall PC. A symptom-level examination of parent-child agreement in the diagnosis of anxious youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:878–886. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000125092.35109.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed T, Kendall PC. Empirically supported therapist relationship building behavior within a cognitive-behavioral treatment of anxiety in youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:498–505. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Gibbons MBC, Hamilton J, Ring-Kurtz S, Gallop R. The dependability of alliance assessments: The alliance-outcome correlation is larger than you might think. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:267–278. doi: 10.1037/a0023668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Gibbons MBC, Hearon B. Does the alliance cause good outcome? Recommendations for future research on the alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43(3):280–285. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Perrin S, Yule W. Social desirability and self-reported anxiety in children: An analysis of the RCMAS Lie Scale. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:311–317. doi: 10.1023/a:1022610702439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRubeis RJ, Feeley M. Determinants of change in cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990;14:469–482. [Google Scholar]

- DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Young PR, Salomon RM, O’Reardon JP, Lovett ML, Gladis MM, Brown LL, Gallop R. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:409–416. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiuseppe R, Linscott J, Jilton R. Developing the therapeutic alliance in child—adolescent psychotherapy. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 1996;5:85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Elvins R, Green J. The conceptualization and measurement of therapeutic alliance: An empirical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1167–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. The performance of the full information maximum likelihood estimator in multiple regression models with missing data. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61:713–740. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Faw I, Hogue A, Johnson S, Diamond GM, Liddle HA. The Adolescent Therapeutic Alliance Scale: Development, initial psychometrics, and prediction of outcome in family-based substance-abuse prevention counseling. Psychotherapy Research. 2005;15:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Feeley M, DeRubeis RJ, Gelfand LA. The temporal relation of adherence and alliance to symptom change in cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:578–582. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer E, McArdle JJ. Longitudinal modeling of development changes in psychological research. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:20–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston L. The concept of the alliance and its role in psychotherapy: Theoretical and empirical considerations. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1990;27:143. [Google Scholar]

- Gaston L, Marmar CR, Thompson LW, Gallagher D. Relation of patient pretreatment characteristics to the therapeutic alliance in diverse psychotherapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:483–489. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston L, Thompson L, Gallagher D, Cournoyer L, Gagnon R. Alliance, technique and their interactions in predicting outcome of behavioral, cognitive, and brief dynamic therapy. Psychotherapy Research. 1998;8:190–209. [Google Scholar]

- Gelso CJ, editor. Working alliance: Current status and future directions: Editor's introduction. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43(3):257–257. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Adding missing-data-relevant variables to FIML-based structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2003;10(1):80–100. [Google Scholar]

- Green J. Annotation: The therapeutic alliance - a significant but neglected variable in child mental health treatment studies. Journal of Child Psychology , Psychiatry. 2006;47:425–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison T. Do changes in coping and the therapeutic alliance in CBT for youth anxiety disorders precede and predict subsequent symptom improvement? New Brunswick: Rutgers University-Graduate School; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley LL, Ho MHR, Zuroff DC, Blatt SJ. The relationship of perfectionism, depression, and therapeutic alliance during treatment for depression: Latent difference score analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:930–942. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley LL, Ho MHR, Zuroff DC, Blatt SJ. Stress reactivity following brief treatment for depression: Differential effects of psychotherapy and medication. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:244–256. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley KM, Weisz JR. Youth versus parent working alliance in usual clinical care: Distinctive associations with retention, satisfaction and treatment outcome. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:117–128. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Dauber S, Stambaugh LF, Cecero JJ, Liddle HA. Early therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in individual and family therapy for adolescent behavior problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:121–129. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO. The alliance in context: Accomplishments, challenges, and future directions. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43(3):258–263. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Symonds BD. Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1991;38(2):139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL, Comer JS, Kendall PC. Parental responses to positive and negative emotions in anxious and non-anxious children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:1–11. doi: 10.1080/15374410801955839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karver MS, Shirk SR, Handelsman JB, Fields S, Crisp H, Gudmundsen G, et al. Relationship processes in youth psychotherapy: Measuring alliance, alliance-building behaviors, and client involvement. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2008;16:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Nock MK. Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: Methodological issues and research recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1116–1129. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Siegel TC, Bass D. Drawing on clinical practice to inform research on child and adolescent psychotherapy: Survey of practitioners. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1990;21:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Weisz JR. Identifying and developing empirically supported child and adolescent treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:19–36. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Marciano PL, Whitley MK. The therapeutic alliance in cognitive-behavioral treatment of children referred for oppositional, aggressive, and antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:726–730. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Whitley M, Marciano PL. Child-therapist and parent-therapist alliance and therapeutic change in the treatment of children referred for oppositional, aggressive, and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:436–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC. Treating anxiety disorders in children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:100. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Chu B, Gifford A, Hayes C, Nauta M. Breathing life into a manual: Flexibility and creativity with manual-based treatments. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1998;5:177–198. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Comer JS, Marker CD, Creed TA, Puliafico AC, et al. In-session exposure tasks and therapeutic alliance across the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:517–525. doi: 10.1037/a0013686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Flannery-Schroeder E, Panichelli-Mindel SM, Southam-Gerow M, Henin A, Warman M. Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: A second randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:366–380. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hedtke KA. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxious Children: Therapist Manual. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: a randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Ollendick TH. Setting the research and practice agenda for anxiety in children and adolescence: A topic comes of age. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2004;11:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Safford S, Flannery-Schroeder E, Webb A. Child anxiety treatment: outcomes in adolescence and impact on substance use and depression at 7.4-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:276–287. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Southam-Gerow MA. Long-term follow-up of a cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety-disordered youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(4):724–730. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna MS, Kendall PC. Exploring the role of parent training in the treatment of childhood anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:981–986. doi: 10.1037/a0016920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knerr M, Bartle-Haring S. Differentiation, perceived stress and therapeutic alliance as key factors in the early stage of couple therapy. Journal of Family Therapy. 2010;32(2):94–118. [Google Scholar]

- Liber JM, McLeod BD, Van Widenfelt BM, Goedhart AW, van der Leeden AJ, Utens EM, Treffers PD. Examining the Relation Between the Therapeutic Alliance, Treatment Adherence, and Outcome of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Children With Anxiety Disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41(2):172–186. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Second edition. New York: John Wiley, Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb KL, Wilson GT, Labouvie E, Pratt EM, Hayaki J, Walsh BT, Agras WS, et al. Therapeutic Alliance and Treatment Adherence in Two Interventions for Bulimia Nervosa: A Study of Process and Outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(6):1097–1107. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macneil CA, Hasty MK, Evans M, Redlich C, Berk M. The therapeutic alliance: is it necessary or sufficient to engender positive outcomes? Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2009;21(2):95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Maramba GG, Nagayama Hall GC. Meta-Analyses of Ethnic Match as a Predictor of Dropout, Utilization, and Level of Functioning. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2002;8(3):290–297. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(3):438–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Dynamic but structural equation modeling of repeated measures data. In: Nesselroade JR, Cattell RB, editors. The Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology. New York: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 561–614. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Cudeck R, du Toit S, Sörbom D. Structural equation modeling: Present and future. A Festschrift in honor of Karl Jö,reskog. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2001. A latent difference score approach to longitudinal dynamic structural analysis; pp. 341–380. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Latent variable modeling of differences in changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:577–605. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Hamagami F. Latent Difference Score Structural Models. In: Collins L, Sayer A, editors. New methods for the analysis of change. Washington, D.C.: APA Press.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Nesselroade JR. Growth curve analysis in contemporary psychological research. In: Schinka JS, Velicer W, editors. Comprehensive handbook of psychology. volume 2 Research Methods in Psychology. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD. Relationship of the alliance with outcomes in youth psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:603–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. User’ guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles: Muthen &Muthen; 2010. Mplus: The comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers. [Google Scholar]

- Nesselroade JR. The warp and the woof of the developmental fabric. In: Downs R, Liben L, Palermo DS, editors. Visions of aesthetics, the environment, and development: The legacy of Joachim F. Wohlwill. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991. pp. 213–240. [Google Scholar]

- Nesselroade JR. Elaborating the differential in differential psychology. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2000;37(4):543–561. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3704_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, King NJ. Empirically supported treatments for children with phobic and anxious disorders: Current status. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:156–167. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto M, Hofmann S. Avoiding Treatment Failures in the Anxiety Disorders. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. Stages of Change in the Modification of Problem Behaviors. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rector NA, Zuroff DC, Segal ZV. Cognitive change and the therapeutic alliance: The role of technical and nontechnical factors in cognitive therapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1999;36(4):320–328. [Google Scholar]

- Riemsma RP, Pattenden J, Bridle C, Sowden AJ, Mather L, Watt IS, Walker A. A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions based on a stages of change approach to promote individual health behaviour change. Health Technology Assessment. 2002;6(24) doi: 10.3310/hta6240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CR. The Necessary and Sufficient Conditions of Therapeutic Personality Change, Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1957;21(2):95–103. doi: 10.1037/h0045357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubak S, Sandboek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of General Practice. 2005;55(513):305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran JD. Breaches in the therapeutic alliance: An arena for negotiating authentic relatedness. Psychotherapy. 1993;30:11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Safran JD, Muran JC. Has the concept of the therapeutic alliance outlived its usefulness? Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43(3):286–291. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Karver MS. Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:452–464. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Karver MS, Brown R. The alliance in child and adolescent psychotherapy. Psychotherapy. 2011;48:17–24. doi: 10.1037/a0022181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Saiz C. The therapeutic alliance in child therapy: clinical, empirical and developmental perspectives. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:713–728. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Child and Parent Versions. London: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Ollendick TH. Evidence-based assessment of anxiety and its disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:380–411. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Pina AA. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS for DSM-IV C/P): Child and parent version. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1973. Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI-C) [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RC, Lushene RE. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu L, Takeuchi DT, Zane NW. Community Mental Health Services for Ethnic Minority Groups: A Test of the Cultural Responsiveness Hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(4):533–540. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman BA, Marker CD, Smith-Janik SB. Automatic associations and panic disorder: Trajectories of change over the course of treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:988–1002. doi: 10.1037/a0013113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman BA, Marker CD, Clerkin EM. Catastrophic misinterpretations as a predictor of symptom change during treatment for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(6):964–973. doi: 10.1037/a0021067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasey MW, MacLeod C. Information-processing factors in childhood anxiety: A review and developmental perspective. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The Developmental Psychopathology of Anxiety. New York, NY: Oxford; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Verduin TL, Kendall PC. Differential occurrence of comorbidity within childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child Adolescence Psychology. 2003;32(2):290–295. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, McLeod BD, Sigman M, Hwang WC, Chu BC. Parenting and childhood anxiety: Theory, empirical findings, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:134–151. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, Barrios V. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Versions. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:335–342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zane N, Sue S, Chang J, Huang L, Huang J, Lowe S, Srinivasan S, et al. Beyond ethnic match: Effects of client-therapist cognitive match in problem perception, coping orientation, and therapy goals on treatment outcomes. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33(5):569–585. [Google Scholar]