Abstract

Background

Twenty percent of Latinos in the U.S. with HIV are unaware of their HIV status, 33% are linked to care late, and 74% do not reach viral suppression. Disparities along this HIV/AIDS care continuum may be present between various ethnic groups historically categorized as Latino.

Objective

To identify differences along the HIV/AIDS care continuum between U.S. Latinos of varying birth countries/regions.

Methods

A systematic review of articles published in English between 2002–2013 was conducted using MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Web of Science. Studies that reported on one or more steps of the HIV/AIDS care continuum and reported results by birth country/region for Latinos were included.

Results

Latinos born in Mexico and Central America were found to be at increased risk of late diagnosis compared with U.S.-born Latinos. No studies were found that reported on linkage to HIV care or viral load suppression by country/region of birth. Lower survival was found among Latinos born in Puerto Rico compared with Latinos born in mainland U.S. Inconsistent differences in survival were found among Latinos born in Mexico, Cuba and Central America.

Discussion

Socio/cultural context, immigration factors and documentation status are discussed as partial explanations for disparities along the HIV/AIDS care continuum.

Keywords: Latinos, Hispanics, health disparities, human immunodeficiency virus, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, country of birth

Introduction

Latinos bear a disproportionate burden in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic. Although they represented approximately 16% of the United States (U.S.) population in 2010,1 Latinos accounted for 20% of new HIV infections in the same year.2 In 2010, Latinos were infected with HIV at a rate of 20.4 per 100,000, compared with 7.3 among non-Latino whites.3 Additionally, the rate of death among persons living with HIV was 7.5 per 100,000 in Latinos compared with 3.5 in non-Latino whites.4

The HIV and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) care continuum is the sequence of stages of care including diagnosis of HIV/AIDS, linkage to/retention in care, prescription of antiretroviral therapy (ART), and viral suppression.5 Each stage on the HIV/AIDS care continuum affects individual and the public’s health. Early ART treatment is associated with a reduction in the number of HIV-related clinical events and the number of HIV transmission events due to decreased viral loads in the person receiving treatment.6 Early ART, however, is only possible through timely diagnosis of HIV, prompt linkage to care, and access to treatment.

Foreign-born Latinos living in the U.S. may not be fully benefiting from an effective HIV/AIDS care continuum. A systematic review of the literature by Chen and colleagues (2012) found that Latinos are at greater risk of delayed HIV diagnosis compared with non-Latino whites, particularly foreign-born Latinos.7 Immigrant Latinos are also at greater risk of late presentation into care compared with non-immigrants.8,9 In addition, although AIDS survival for Latinos compared with non-Latinos is similar, foreign-born Latinos experience shorter survival compared with US.-born individuals.7 Thus, disparities along the HIV/AIDS care continuum between foreign-born Latinos and U.S.-born individuals have been identified; however, additional disparities might exist among Latinos originating from the various regions of Latin America.

Latinos in the U.S. have been historically categorized as one large monolithic ethnic group; however, differences exist by country/region of birth.10 First, Latinos in the U.S. differ in lifestyles, cultural norms, and values. The Pew Research Center showed that 69% of Latinos in the U.S. believe that Latinos represent multiple cultures; 51% use their country of origin to describe themselves; and only 24% use Hispanic/Latino.13 Given the large number of Mexicans in the U.S. and the geographic vicinity, Latinos born in Mexico are able to retain a strong Mexican cultural identity.11 Second and third generation Mexicans are more likely to speak Spanish at home than their Cuban counterparts.12 Puerto Ricans, however, have been influenced more heavily by American culture.11 These cultural differences, as well as differential exposure to HIV in their home country may impact HIV knowledge, testing and healthcare seeking behaviors, and perceived stigma.14 In addition, Latinos also differ in HIV risk behaviors. Injection drug use is reported more frequently as a mode of HIV transmission among people born in Puerto Rico compared with Latinos born in other areas.15

Second, while 55% of Latinos immigrate to the U.S. for economic opportunities,13 such as many persons born in Mexico,16 others immigrate for political reasons, such as many Latinos born in Cuba. These differences in immigration rationale overlap with observed differences in socioeconomic status (e.g., education and income levels) among Latino groups in the U.S.10 Latinos in the U.S. who are born in Cuba and South American report higher levels of education and experience less poverty than those born in Mexico and Central America.17 For example, 32% of Colombians living in the U.S. have received a bachelor’s degree or higher compared with 13% of all Latinos, and only 13% live in poverty, compared with 25% of all Latinos. Conversely, only 9% of Latinos born in Mexico and living in the U.S. have a bachelor’s degree or higher, and 27% live in poverty.17

Third, access to health care can vary by birth country for U.S. Latinos. Cuban immigrants, along with their spouse and children, can become legal permanent U.S. residents and access government healthcare and social services similar to a native.18 Latinos born in Puerto Rico (a commonwealth of the U.S.) also have similar benefits to U.S. citizens. On the other hand, Latinos in the U.S. born in Mexico, Central and South America, and other Caribbean countries who arrive to the U.S. undocumented do not benefit from these policies. Forty-six percent of Salvadorians, 60% of Guatemalans and 68% of Hondurans living in the U.S. were undocumented in 2009.19 Fifteen percent of Puerto Ricans and 25% of Cubans in the U.S. lacked health insurance in 2010, while between 41% and 50% of Hondurans, Guatemalans, and Salvadorians were uninsured.17 Finally, differential health outcomes among Latinos by birth country/region also have been indicated for other diseases such as asthma,20 diabetes,21 and hypertension.22

Despite the diversity in the U.S. Latino population, few studies have evaluated the steps along the HIV/AIDS care continuum for Latinos by birth country/region.15,23–27 The current systematic review presents the published literature regarding diagnosis, linkage to and retention in care, prescription of ART and health outcomes for Latinos living with HIV/AIDS in the U.S by birth country/region. The objective of the review was to identify potential disparities along the HIV/AIDS care continuum between Latinos of varying birth countries living in the U.S. with HIV/AIDS. Based on previously outlined cultural/behavioral differences, socioeconomic status, and healthcare access between these groups, we hypothesized that Latinos born in Mexico, Central America, and Puerto Rico may have worse outcomes in comparison to their U.S., Cuban, and South American counterparts.

Methods

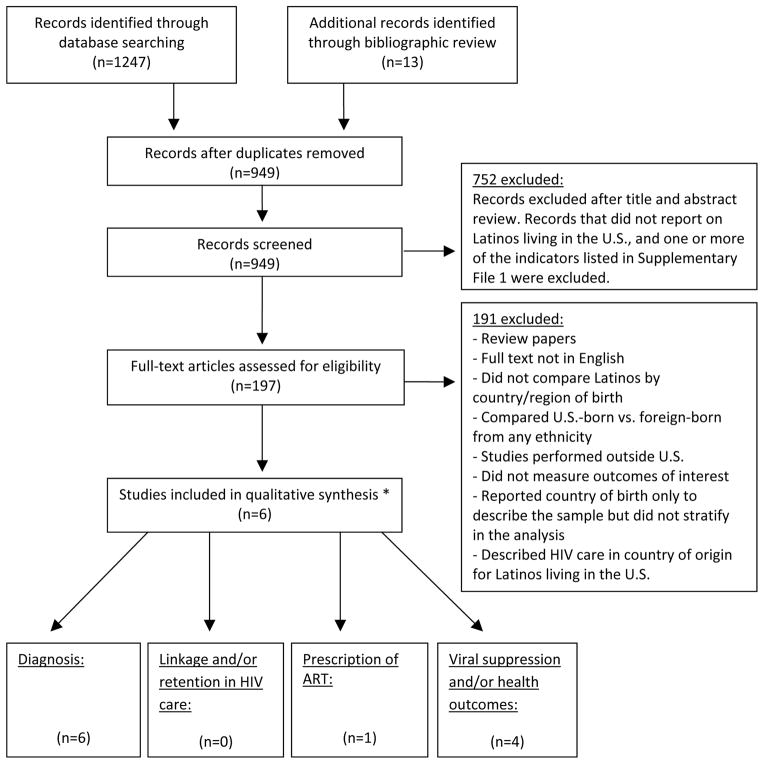

We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Web of Science for articles published between January 1, 2002 and September 1, 2013. The following search terms were used: “AIDS”, “acquired immune deficiency syndrome”, “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome”, “HIV”, “human immune deficiency virus”, or “human immunodeficiency virus” in the title. Additionally, a combination of key terms related to birth country and the HIV/AIDS care continuum was used (Supplementary File 1). Articles were reviewed that met the following inclusion criteria: 1) focused on Latinos living in the U.S., 2) included persons 13 years or older, 3) reported on pre-identified HIV/AIDS care continuum indicators, 4) were published in a peer-reviewed journal, and 5) were published in English. A comprehensive list of indicators for monitoring HIV care in the U.S. was identified by the authors by searching the literature for varying definitions and measurement methods used for each step in the HIV/AIDS care continuum in any population, and not only Latinos. Additional articles were identified through a bibliographic review of selected articles and relevant reviews. Review articles and studies that did not stratify the analysis by birth country/region were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search methods and selection of manuscripts

*Four articles presented data on more than 1 category

The following variables were extracted: 1) author and publication year, 2) study type, 3) data source, 4) study period, 5) location, 6) study population 7) sample size, 8) birth country classification, 9) outcome assessed, and 10) results. The first author conducted the initial review of the literature and data extraction. The second and third author reviewed both the tabulated results and the original articles to ensure that studies met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Two articles were excluded during this step because they examined only individuals born in Haiti. The authors followed the applicable PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews.28

Results

The above-mentioned search initially revealed 936 potentially relevant manuscripts, plus an additional 13 from bibliographic reviews. One hundred and ninety-seven articles were identified for full review. Six studies reported on Latinos by birth country/region for one or more stages of the HIV/AIDS care continuum.15,23–27 Four articles presented data on more than one care category. All articles reported on delayed diagnosis (Table 1),15,23–27 and one article reported on ART prescription (Table 2).26 No articles were identified which analyzed linkage to or retention in HIV/AIDS care, or viral load suppression for Latinos by birth country/region. However, four articles reported on other outcomes including opportunistic infections,26 mortality23 and survival,15,23,24,26 and are included in this review (Table 2).

Table 1.

Studies on diagnosis of HIV/AIDS for Latinos by country/region of birth

| First author, pub. year [ref. no.] |

Study type | Source of data, year, location, study population |

Total sample size |

Race/ethnicity/ country/region of birth classification |

Outcome related to continuum of care |

Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Espinoza, 2012 [24] |

Retrospective cohort | CDC national surveillance, 2006 – 2009, 40 states and Puerto Rico, all HIV cases among those Hispanic/Latinos and 13 years or older | 33,498 |

|

Short HIV-to-AIDS interval (AIDS less than 12 months after HIV diagnosis) | Short HIV-to-AIDS interval: | ||

| PR (95% CI) | APR*(95% CI) | |||||||

| U.S.-born Latino: | Referent | Referent | ||||||

| Foreign-born Latino: | 1.3 (1.24, 1.33) | 1.2† (1.16, 1.24) | ||||||

| *Adjusted for covariates | ||||||||

| † Differences in groups were considered significant if the 95% CI for the APR did not include 1.0. | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Espinoza, 2008 [15] |

Retrospective cohort | CDC national surveillance, 2003 – 2006, 33 states and U.S. dependent areas, all HIV cases among Hispanics/Latinos | 30,415 |

|

Short HIV-to-AIDS interval (AIDS less than 12 months after HIV diagnosis) | Short HIV-to-AIDS interval: | ||

| OR (95% CI) | AOR* (95% CI) | |||||||

| U.S.-born Latino: | Referent | Referent | ||||||

| Puerto Rico: | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | ||||||

| Cuba: | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.8 (0.7, 1.0) | ||||||

| Mexico: | 1.9 (1.6, 2.2) | 2.2† (1.8, 2.5) | ||||||

| Central America: | 2.2 (1.8, 2.7) | 2.5† (2.0, 3.2) | ||||||

| South America: | 0.8 (0.7, 1.1) | 0.8 (0.7, 1.0) | ||||||

| Other: | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | ||||||

| Unknown: | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.0) | ||||||

| *Adjusted for sex, age group, place of birth, and transmission category | ||||||||

| † Differences in groups were considered significant if the 95% CI for the AOR did not include 1.0. | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Hanna, 2008 [23] | Retrospective cohort | New York City HIV/AIDS reporting system, January, 2002 – June, 2005, NYC, NY, all New York City residents at time of AIDS diagnosis | 15,211 |

|

Concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnosis | Concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnosis: | ||

| Concurrent diagnosis (%) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born (any race/ethnicity): | 20.8 | |||||||

| Puerto Rico: | 19.5 | |||||||

| Other Caribbean/West Indies: | 38.3 | |||||||

| Central/South America: | 36.3 | |||||||

| Other countries: | 37.2 | |||||||

| Unknown: | 26.5 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Tang, 2011 [25] |

Retrospective cohort | California Office of AIDS, 2000 – 2006, California, all AIDS cases 13 years or older reported through November 1, 2007 | 28,382 |

|

Late HIV testing (HIV diagnosis within 12 months preceding AIDS diagnosis) | Late HIV testing adjusted for gender: | ||

| AOR* (95% CI) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born white: | Referent | |||||||

| U.S.-born Latino: | 2.0† (1.8, 2.1) | |||||||

| U.S.-born black: | 1.2† (1.1, 1.3) | |||||||

| U.S.-born other: | 1.6† (1.3, 1.9) | |||||||

| Foreign-born/other: | 2.1† (1.8, 2.3) | |||||||

| Mexico-born: | 3.4† (3.1, 3.7) | |||||||

| Foreign-born/Latino: | 2.1† (1.9, 2.4) | |||||||

| * Controlled for gender | ||||||||

| † P-value <0.001 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Wohl, 2009 [27] |

Population based, cross-sectional | Supplement to HIV/AIDS surveillance project, 2000 – 2004, Los Angeles County, CA, all AIDS cases 18 years or older | 383 |

|

Late HIV testing (first HIV diagnosis within 12 months of AIDS diagnosis) | Late HIV tester: | ||

| OR (95% CI) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born Latino: | Referent | |||||||

| Mexico: | 2.2 (1.3, 3.8) | |||||||

| Central America: | 3.0 (1.5, 5.9) | |||||||

| Other: | 1.7 (0.4, 7.3) | |||||||

| OR (95% CI) | AOR* (95% CI) | |||||||

| U.S.-born Latino: | Referent | Referent | ||||||

| Foreign-born Latino: | 2.4 (1.4, 4.0) | 0.9 (0.4, 2.0) | ||||||

| * Adjusted for age, county of birth, education, and IDU | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Wohl, 2003 [26] |

Medical records-based observational cohort | Adult/Adolescent Spectrum of HIV Disease Study, 1996– 2000, Los Angeles, CA, HIV infected patients from 2 large public HIV clinics, 1 private and 1 HMO | 803 |

|

Reason tested for HIV | Reason tested for HIV: | ||

| Illness (%) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born Latinos: | 32 | |||||||

| Mexican-born: | 25 | |||||||

| Central American-born: | 19 | |||||||

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; AIDS, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

PR, Prevalence Ratio; APR, Adjusted Prevalence Ratio; AOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; OR, Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval.

IDU, injection drug use.

U.S., United States; NYC, New York City; CA, California; HMO, Health Maintenance Organization.

Table 2.

Studies on HIV/AIDS outcomes for Latinos by country/region of birth

| First author, pub. year [ref. no.] | Study type | Source of data, year, location, study population | Total sample size | Race/ethnicity/country of birth classification | Outcome related to continuum of care | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Espinoza, 2012 [24] |

Retrospective cohort | CDC national surveillance, 2001 – 2005, 40 states and Puerto Rico, all HIV cases among those Hispanic/Latinos and 13 years or older | 41,680 |

|

Survival (12 and 36 months after AIDS diagnosis) | Survival: | |||

| 12 months % (95% CI) | 36 months % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born Latino: | 94 (93, 94) | 91 (90, 91) | |||||||

| Foreign-born Latino: | 91 (91, 92) | 88 (88, 89) | |||||||

| Central America: | 91 (90, 93) | 88 (87, 90) | |||||||

| Cuba: | 93 (92, 94) | 89 (88, 91) | |||||||

| Mexico: | 90 (89, 91) | 88 (87, 89) | |||||||

| Puerto Rico: | 92 (91, 92) | 88 (87, 89) | |||||||

| South America: | 96 (95, 97) | 93 (92, 94) | |||||||

| Other: | 94 (93, 95) | 90 (88, 91) | |||||||

| Unknown: | 95 (95, 96) | 93 (93, 94) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Espinoza, 2008 [15] |

Retrospective cohort | CDC national surveillance, 1996 – 2003, 33 states and U.S. dependent areas, all HIV cases among Hispanics/Latinos | 68,382 |

|

Survival (12 and 36 months after AIDS diagnosis) | Survival: | |||

| 12 months % (95% CI) | 36 months % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born Latino: | 87.4 (87.2, 87.6) | 80.8 (80.6, 81.0) | |||||||

| Puerto Rico: | 81.0 (80.7, 81.3) | 73.6 (73.4, 73.8) | |||||||

| Cuba: | 83.1 (82.8, 83.5) | 74.6 (74.3, 74.9) | |||||||

| Mexico: | 86.4 (86.2, 86.5) | 81.6 (81.4, 81.7) | |||||||

| Central America: | 87.8 (87.7, 88.0) | 83.4 (83.3, 83.5) | |||||||

| South America: | 88.5 (88.4, 88.7) | 84.0 (83.9, 84.1) | |||||||

| Other: | 86.2 (85.8, 86.6) | 80.6 (80.5, 80.7) | |||||||

| Unknown: | 92.8 (92.6, 92.9) | 88.2 (88.0, 88.3) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Hanna, 2008 [23] |

Retrospective cohort | New York City HIV/AIDS reporting system, January, 2002 – June, 2005, NYC, NY, all New York City residents at time of AIDS diagnosis | 15,211 |

|

HIV- related mortality (death occurring after AIDS diagnosis with underlying cause of HIV infection or opportunistic infection) | HIV-related death: | |||

| AHR* (95% CI) | |||||||||

| U.S.-born or unknown: | Referent | ||||||||

| Puerto Rico: | 2.5 (2.04, 3.15) | ||||||||

| Other Caribbean/West Indies: | 1.7 (1.47, 2.05) | ||||||||

| Central and South America: | 1.7 (1.29, 2.12) | ||||||||

| Other: | 1.1 (0.87, 1.43) | ||||||||

| *Adjusted for gender and borough of residence | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Wohl, 2003 [26] |

Observational cohort | Adult/Adolescent Spectrum of HIV Disease Study, 1996– 2000, Los Angeles, CA, HIV infected patients from 2 large public HIV clinics, one private and one HMO | 803 |

|

Prescription of ART Opportunistic infections |

Prescription of ART: | |||

| U.S.-born Latinos (%) | Mexican (%) | Central American (%) | |||||||

| HAART | 55 | 60 | 57 | ||||||

| Dual ARV | 11 | 9 | 14 | ||||||

| Other PI | 19 | 15 | 14 | ||||||

| Other NNRTI | 3 | 3 | 5 | ||||||

| Other | 4 | 5 | 5 | ||||||

| No regimen | 8 | 8 | 5 | ||||||

| Opportunistic infections: | |||||||||

| HR* (95% CI) | |||||||||

| Latino males and females | |||||||||

| U.S.-born vs. foreign-born: | 1.3(0.9, 1.7) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born vs. Mexican-born: | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born vs. Central American-born: | 1.6 (1.0, 2.5) | ||||||||

| Latino males only | |||||||||

| U.S.-born vs. foreign-born: | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born vs. Mexican-born: | 1.3 (0.9, 2.0) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born vs. Central American-born: | 0.8 (0.4, 1.6) | ||||||||

| Latino females only: | |||||||||

| U.S.-born vs. foreign-born: | 1.5 (0.8, 2.8) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born vs. Mexican-born: | 0.9 (0.4, 1.7) | ||||||||

| U.S.-born vs. Central American-born: | 2.9† (1.3, 6.5) | ||||||||

| *Adjusted for age, CD4 count, and HAART use prior to opportunistic infection | |||||||||

| † P-value = 0.012 | |||||||||

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; AIDS, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

AHR, Adjusted Hazards Ratio; HR, Hazards Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval.

HAART, Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy.

U.S., United States; NYC, New York City; CA, California; HMO, Health Maintenance Organization.

Diagnosis of HIV/AIDS

Among the six articles reporting on delayed diagnosis (Table 1), four defined delayed diagnosis by an HIV-to-AIDS interval of less than 12 months.15,24,25,27 Hanna et al. defined delayed diagnosis by a concurrent HIV and AIDS diagnosis,23 and Wohl et al. (2003) inferred delayed diagnosis from the reason for HIV testing, such as illness, new relationship, or surgery.26 Of these 6 studies, 4 reported on at least 3 birth places: U.S, Mexico, and Central America.15,23,26,27 Additionally, Tang and colleagues compared Mexico-born individuals with non-Latinos, U.S.- and foreign-born Latinos only.25 Espinoza et al. (2008) separated Cuba, Central, and South America for analysis.15 Hanna et al. analyzed Latinos born in the Caribbean (excluding Puerto Rico) and West Indies as one separate category.23

Odds ratios for a short HIV-to-AIDS interval were significantly higher across all studies for Latinos born in Mexico and Central America.15,25,27 Espinoza (2008) – the only study that reported odds ratios for Puerto Rico, Cuba and South America separately – did not find an elevated odds ratios for being born in these countries/regions and delayed HIV/AIDS diagnosis compared with U.S.-born Latinos.15 Hanna found a lower proportion of Latinos born in Puerto Rico diagnosed concurrently with HIV and AIDS compared with Latinos born in mainland U.S.; however, it is unclear if the difference is significant.23 Wohl (2003), the only study reporting a higher proportion of U.S.-born Latinos diagnosed late, used testing due to symptoms as an indicator of late testing.26 A larger proportion of U.S.-born Latinos were tested for HIV due to illness compared with Mexican- and Central American-born Latinos.26

Linkage to and retention in HIV/AIDS care

Our review did not identify articles reporting on linkage to/retention in HIV care for Latinos by birth country/region.

Prescription of ART

Wohl et al. (2003) reported on ART for Latinos with HIV by birth country/region (Table 2).26 A smaller proportion of U.S.-born Latinos were prescribed highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) compared with Mexican- and Central American-born Latinos; however, these differences were not statistically significant. A higher percentage of Mexican- and U.S.-born Latinos reported no ART prescription when compared with Central American-born Latinos, but statistical difference was not reported.

Viral suppression and health outcomes

No articles were found that reported measures of viral load suppression for Latinos by birth country/region. Four articles were identified on other health outcomes (Table 2).15,23,24,26 Of these four articles, Espinoza (2008 and 2012) reported on survival,15,24 Hanna on HIV-related mortality,23 and Wohl (2003) on opportunistic infections.26 All studies reported on several birth places including the U.S. and Central America.15,23,24,26 Only the studies by Espinoza and colleagues separated Cuba and Central America from South America,15,24 and only Hanna et al. separated Caribbean/West Indies during analysis.23

Findings for health outcomes by birth country/region for Latinos varied across studies. Espinoza (2012) found a significantly lower percentage of Latinos born in Mexico and Puerto Rico surviving at 36 months post AIDS diagnosis compared with Latinos born in the U.S. and South America.24 A lower percentage of Latinos born in the U.S. were alive at 12 and 36 months compared with Latinos born in South America. Espinoza’s earlier study published in 2008, however, showed significantly lower survival at 36 months among Latinos born in Puerto Rico and Cuba when compared with Latinos born in the U.S., Mexico, Central and South America.15 The study also found a lower percentage of U.S.-born Latinos alive at 12 months compared with Latinos born in Central and South America, and at 36 months compared with those born in Mexico, Central and South America. Based on 95% confidence intervals shown in table 2, both of these studies found a significantly higher percentage of U.S.-born and South American-born Latinos, as well as those with unknown country of birth, alive at 12 and 36 months after diagnosis compared with Latinos born in Puerto Rico. Hanna and colleagues found an increased risk of HIV-related death for Puerto Ricans, other Caribbean/West Indies, and Central and South Americans compared with U.S.-born Latinos.23

In contrast, Wohl (2003) showed that U.S.-born Latinos had an increased risk of opportunistic infections compared with foreign-, Central American- and Mexican-born Latinos, although not statistically significant after adjusting for age and CD4 count.26 However, when stratifying by gender, U.S.-born females had a statistically significant elevated risk of opportunistic infections compared with Central American-born Latinas (HR 2.9, 95% CI 1.3–6.5).

Discussion

Our findings indicate that Latinos born in Mexico and Central America are at an increased risk of late diagnosis compared with those born in the U.S., Puerto Rico, Cuba, and South America.15,23,25,27 Our review also found patterns of lower survival among Latinos born in Puerto Rico compared with U.S.- and South American-born Latinos.15,24 Risk of mortality was inconsistent across studies for Latinos born in Mexico, Cuba and Central America.15,24 Although no studies analyzed linkage to/retention in HIV care for Latinos by birth country/region, a representative study of general (not HIV/AIDS) healthcare utilization found that Latinos born in Mexico, Cuba, Central America/Caribbean and South America reported fewer ambulatory care visits than those born in Puerto Rico.29 Cubans and Puerto Ricans were less likely to spend the entire year uninsured. Those who were uninsured were less likely to use health services than those with private health insurance. Thus, future research is needed to examine whether these trends maintain across regions of origin for linkage to/retention in HIV care.

Disparities among Latinos by birth country/region may relate to: 1) socio/cultural context, and/or 2) immigration factors and documentation status. A higher percentage of Latinos born in Puerto Rico are infected through injection drug use (33%) compared with any other Latino group, and compared with Latinos as a whole (18%).15 Latinos infected with HIV through injection drug use experience lower survival than any other transmission category.15, 23 A qualitative study by Shedlin and Shulman found that Latino participants with HIV from countries with less HIV experience (e.g., Guatemala) attributed HIV infection with prostitution and homosexuality and that these beliefs negatively impacted their care-seeking behaviors.14 Participants also stated that poverty in their home country, pride, denial, shame and fear stopped them from seeking care. While many participants expressed high levels of stigma in their home country, few experienced discrimination in HIV care in the U.S., and most were satisfied with their healthcare provider. Individuals whose provider spoke Spanish experienced higher levels of satisfaction. Low levels of satisfaction with HIV care has been linked to poor ART adherence.30 Therefore, language proficiency may play a role in disparities in HIV/AIDS outcomes among Latinos, as South Americans are more likely to speak English fluently17 and may be more likely to effectively communicate with non-Spanish speaking providers.

Reasons for immigration (e.g. political, economic, familial), levels of educational attainment, and poverty all vary across birth countries of Latino immigrants. For example, Latinos born in Colombia, Peru and Cuba report higher levels of education and less poverty than those born in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.17 Studies have linked lower levels of education and higher levels of poverty to reduced HIV testing31 and increased risk of HIV-related death32 that may explain, in part, why Latinos born in Mexico and Central America are more likely to be diagnosed late compared with Latinos born in Cuba and South America. However, only Espinoza’s most recent study found that Latinos with HIV born in Mexico experience shorter survival after an AIDS diagnosis, while those born in Central America experienced similar survival compared with U.S.-born Latinos.24 Furthermore, Espinoza’s 2008 study found that Latinos born in Mexico and Central America have longer survival compared with U.S.-born Latinos.15 The same study found that Latinos born in Cuba have shorter survival than U.S.-born Latinos. These findings suggest that socioeconomic status is not an important predictor of AIDS survival among Latinos.

Differences in immigration laws for Latinos born in Cuba and Puerto Rico compared with Latinos born elsewhere can affect healthcare access differentially.18 Immigration laws, in part, lead to a larger percentage of Mexican- and Central American-born Latinos to be undocumented in comparison to their counterparts.19 Undocumented Latinos are less likely to have a primary care physician, and access to care and government services than all Latinos35 partly for fear of deportation and lack of health insurance.36 These barriers may be affecting access to care for Latinos born in Mexico and Central America more compared with Latinos from countries with opportunities for permanent legal U.S. residency that may be putting them at an additional risk for delayed HIV/AIDS diagnosis. Nevertheless, although Latinos born in Puerto Rico are not affected by immigration laws, our study found them to be at increased risk of mortality. Furthermore, Espinoza (2008) found Latinos born in Mexico and Central America surviving longer, and those born in Cuba surviving shorter after an AIDS diagnosis compared with U.S.-born Latinos.15 These findings suggest that documentation status might be impacting HIV testing but not survival.

In addition to socio/cultural context and immigration factors, the healthy migrant effect (i.e., the idea that those who immigrate are healthier than the native-born) and salmon bias (i.e., the idea that less-healthy immigrants return to their birth country) may play a role in disparities between U.S.-born and foreign-born Latinos.33 These theories may hold for Latinos born in certain countries/regions of birth and not others given differences in the reason for immigrating and the ability to travel back to their home country. Two of the studies identified found that U.S.-born Latinos had shorter survival than some foreign-born groups. A recent meta-analysis by Ruiz and colleagues found evidence for a Latino mortality advantage for healthy individuals and those with cardiovascular disease, but failed to find a mortality advantage for Latinos with HIV/AIDS.34 Ruiz’s findings suggest that Latinos with HIV/AIDS are not returning to their home country after becoming ill, and instead continue to utilize HIV/AIDS care resources throughout the course of their illness and be impacted by U.S. healthcare policies.

The studies identified have several limitations. Although the studies reported differences in the risk of delayed HIV diagnosis and health outcomes by birth country/region, they did not examine the specific demographic predictors for the varied ethnic groups. Predictors were instead reported for the whole Latino population. This limits our understanding and ability to report the specific factors that act as barriers or facilitators along the HIV/AIDS care continuum for each Latino ethnic group. In addition, only Wohl (2009) examined length of time in the U.S. and preferred language as a predictor of delayed HIV diagnosis for Latinos as a whole. 27 No study included measures such as documentation status, and perceived stigma and discrimination, factors that may differ by birth country/region. Finally, most of the studies identified controlled for variables such as sex, age, and transmission category but did not adjust for or stratify by socioeconomic status despite the differences among Latinos of varying origins. This is likely a function of the limitations of surveillance data, which does not collect individual level socioeconomic status.

Future research should attempt to maintain consistency in the stratification of Latinos when examining birth country/region differences to allow for comparison between studies. Although regions such as South and Central America are often investigated, cultural, political and socioeconomic differences within these regions may exist, and birth country should be used when possible. Future research should focus on studying the factors that differ between Latinos of varying birth countries as potential contributors to the increased risk of delayed diagnosis or linkage to care such as income, education, employment and insurance status. Additionally, studies investigating access to HIV/AIDS care and viral load suppression by birth country/region are needed as none were identified. Finally, in addition to birth country/region, research should also be focused on stratifying Latinos by characteristics like documentation status, English proficiency, and length of time in the U.S., as these may be important in the design of interventions and policy recommendations.

Our systematic review is not without limitations. First, the small number of studies found limits our ability to draw conclusions from our findings for some steps in the HIV/AIDS care continuum. Second, the geographic location of the studies varied and may differ significantly in availability of resources and culturally appropriate services for Latinos. A given study’s location may also impact perceived stigma and discrimination for Latinos in general, and for people living with HIV/AIDS.37 Third, although our methodology attempted to conduct a wide and comprehensive initial search, some studies may have been missed due to the relatively large number of outcome variables and ways to measure each step of the HIV/AIDS care continuum. Fourth, we searched the literature published in English since our focus was on Latinos living in the U.S. This strategy may have limited us in finding all relevant articles, particularly those published in Spanish. Finally, our study narrowed the search to articles published after 2002 in an effort to report data from the most recent 10-year period.

Nevertheless, our literature review has highlighted differences along the HIV/AIDS care continuum between Latinos of varying origins. Changes in documentation requirements for government health insurance and social services access should be considered to address factors that stem from documentation status, whether or not related to country/region of birth. In conjunction with policy changes, public health professionals must consider differences in socioeconomic patterns, sources of stigma and HIV risk behaviors between Latinos of varying birth countries when designing secondary and tertiary HIV prevention programs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Award Number [P20MD002288] and [5R01MD004002] from the National Institute on Minority Health & Health Disparities (NIMHD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ennis S, Rios-Vargas M, Albert N. The Hispanic population: 2010. United States Census Bureau; May, 2011. See http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report: diagnosis of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2010. 2012 Mar;22 See http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010report/pdf/2010_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_22.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Geographic differences in HIV infection among Hispanics or Latinos - 46 states and Puerto Rico, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(40):805–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCHHSTP Atlas. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Jan 15, 2014. See http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/NCHHSTPAtlas/main.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P, et al. Differences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(14):1337–44. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen NE, Gallant JE, Page KR. A systematic review of HIV/AIDS survival and delayed diagnosis among Hispanics in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(1):65–81. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9497-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelley CF, Hernandez-Ramos I, Franco-Paredes C, del Rio C. Clinical, epidemiologic characteristics of foreign-born Latinos with HIV/AIDS at an urban HIV clinic. AIDS Read. 2007;17(2):73–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy V, Prentiss D, Balmas G, et al. Factors in the delayed HIV presentation of immigrants in Northern California: implications for voluntary counseling and testing programs. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9(1):49–54. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivera FI, Guarnaccia PJ, Mulvaney-Day N, et al. Family cohesion and its relationship to psychological distress among Latino groups. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2008;30(3):357–78. doi: 10.1177/0739986308318713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guarnaccia PJ, Martinez I. Mental health in the Hispanic immigrant community: an overview. J Immigr Refug Serv. 2005;3:21–46. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alba R, Logan J, Lutz A, Stults B. Only English by the third generation? Loss and preservation of the mother tongue among the grandchildren of contemporary immigrants. Demography. 2002;39(3):467–84. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor P, Lopez ML, Martinez JH, Velasco G. When label’s don’t fit: Hispanics and their views of identity. Pew Research Center; Apr 4, 2012. See http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2012/04/PHC-Hispanic-Identity.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shedlin MG, Shulman L. Qualitative needs assessment of HIV services among Dominican, Mexican and Central American immigrant populations living in the New York City area. AIDS Care. 2004;16(4):434–45. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001683376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espinoza L, Hall HI, Selik RM, Hu X. Characteristics of HIV infection among Hispanics, United States 2003–2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(1):94–101. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181820129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Passel J, Cohn D, Gonzalez-Barrera A. Net migration from Mexico Falls to Zero- and perhaps less. Pew Research Center; Apr 23, 2012. See http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2012/04/Mexican-migrants-report_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motel S, Patten E. The 10 largest Hispanic origin groups: characteristics, rankings, top counties. Pew Research Center; Jun 27, 2012. See http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2012/06/The-10-Largest-Hispanic-Origin-Groups.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasem RE. Cuban migration to the United States: policy and trends. Congressional Research Service; Jun 2, 2009. See http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R40566.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenblum MR, Brick K. US immigration policy and Mexican/Central American migration flows: then and now. Migration Policy Institute; Aug, 2011. See http://www.migrationpolicy.org/pubs/rmsg-regionalflows.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis AM, Kreutzer R, Lipsett M, et al. Asthma prevalence in Hispanic and Asian American ethnic subgroups: results from the California Healthy Kids Survey. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):e363–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borrell LN, Crawford ND, Dallo FJ, Baquero MC. Self-reported diabetes in Hispanic subgroup, non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic white populations: National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2005. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(5):702–10. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zambrana RE, Ayala C, Pokras OC, et al. Disparities in hypertension-related mortality among selected Hispanic subgroups and non-Hispanic white women ages 45 years and older--united states, 1995–1996 and 2001–2002. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(3):434–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV, Sackoff JE. Concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnosis increases the risk of short-term HIV-related death among persons newly diagnosed with AIDS, 2002–2005. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(1):17–28. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Espinoza L, Hall HI, Hu X. Diagnoses of HIV infection among Hispanics/Latinos in 40 states and Puerto Rico, 2006–2009. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(2):205–13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824d9a29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang JJ, Levy V, Hernandez MT. Who are California’s late HIV testers? an analysis of state AIDS surveillance data, 2000–2006. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(3):338–43. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wohl AR, Lu S, Turner J, et al. Risk of opportunistic infection in the HAART era among HIV-infected Latinos born in the United States compared to Latinos born in Mexico and Central America. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17(6):267–75. doi: 10.1089/108729103322108148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wohl AR, Tejero J, Frye DM. Factors associated with late HIV testing for Latinos diagnosed with AIDS in Los Angeles. AIDS Care. 2009;21(9):1203–10. doi: 10.1080/09540120902729957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA Statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinick RM, Jacobs EA, Stone LC, et al. Hispanic healthcare disparities: challenging the myth of a monolithic Hispanic population. Med Care. 2004;42(4):313–20. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000118705.27241.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy DA, Roberts KJ, Martin DJ, et al. Barriers to antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected adults. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14(1):47–58. doi: 10.1089/108729100318127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez-Quintero C, Shtarkshall R, Neumark YD. Barriers to HIV-testing among Hispanics in the United States: analysis of the National Health Interview Survey, 2000. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19(10):672–83. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joy R, Druyts EF, Brandson EK, et al. Impact of neighborhood-level socioeconomic status on HIV disease progression in a universal health care setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(4):500–5. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181648dfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markides KS, Eschbach K. Aging, migration, and mortality: current status of research on the Hispanic paradox. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(Spec2):68–75. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruiz JM, Steffen P, Smith TB. Hispanic mortality paradox: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the longitudinal literature. Am J Public Health. 2013;10(3):e52–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berk ML, Schur CL, Chavez LR, Frankel M. Health care use among undocumented Latino immigrants. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19(4):51–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.4.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dang BN, Giordano TP, Kim JH. Sociocultural and structural barriers to care among undocumented Latino immigrants with HIV infection. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(1):124–31. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. Am Psychol. 2010;65(4):237–51. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]