Abstract

Giant cell reparative granulomas (GCRGs) are lytic lesions that occur predominantly in the gnathic bones and occasionally in the small bones of the hands and feet. They are morphologically indistinguishable from, and are regarded as synonymous with, solid variant of aneurysmal bone cysts (ABC) in extra-gnathic sites. Identification of USP6 gene rearrangements in primary ABC has made possible investigating potential pathogenetic relationships with other morphologic mimics. USP6 gene alterations in giant-cell rich lesions (GCRG / ABC) of small bones of the hands and feet have not been previously studied. We investigated USP6 gene alterations in a group of 9 giant-cell rich lesions of the hands and feet and compared the findings with morphologically similar lesions including 8 gnathic GCRGs, 22 primary ABCs, 8 giant cell tumors (GCT) of bone and 2 brown tumors of hyperparathyroidism. Overall, there were 49 samples from 48 patients including 26 females and 22 males. Eight of the 9 (89%) lesions of the hands and feet showed USP6 gene rearrangements, while no abnormalities were identified in the 8 gnathic GCRGs, 2 brown tumors or 8 GCTs of bone. Thirteen of the 22 (59%) primary ABCs showed USP6 gene rearrangements. In conclusion, most GCRGs of the hands and feet represent true ABCs and should be classified as such. The terminology of GCRG should be limited to lesions from gnathic location. FISH for USP6 break-apart is a useful ancillary tool in the diagnosis of primary ABCs and distinguishing them from GCRGs and other morphologically similar lesions.

Keywords: USP6, Giant cell reparative granuloma, solid ABC

INTRODUCTION

Giant cell reparative granuloma (GCRG) was first described by Jaffe in 1953 as a benign non-neoplastic process related to intraosseous hemorrhage and limited to the gnathic sites, either mandible or maxilla.[1] In 1962, Ackerman and Spjut reported two lesions involving the phalanges which they termed ‘giant cell reaction’, defined as ‘a rare, benign, non-neoplastic lesion involving small bones of the hands’.[2] In 1980, Lorenzo and Dorfman, published the first larger series of 8 cases of ‘giant cell reparative granulomas of the short bones of the hand and feet’ and reported their recurrence potential, with 4 of 8 lesions recurring one or more times.[3] They also noted the morphologic similarity to other giant cell-rich lesions, such as aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) and GCRG of the mandible and maxilla and hypothesized that these lesions are related responses to intraosseous hemorrhage. Gnathic GCRGs have been also termed as central giant cell lesions or central giant cell granulomas.

The terminology of ‘solid aneurysmal bone cyst’ was introduced by Sanerkin et al.[4] in 1983, who reported 4 cases of a non-cystic lesion involving bone (three in the spine and one in the ethmoid), with morphologic features similar to that seen in ABC. They also noted the histologic overlap with other giant cell rich lesions, including GCRG. Ratner and Dorfman,[5] in 1989, reported additional 20 cases of GCRG of hands and feet and re-emphasized the difficult distinction of solid areas of ABC from GCRG. Subsequently, Bertoni et al.,[6] Oda et al.[7] and Ilaslan et al.[8] reported lesions with similar morphology in the long bones and designated them as solid ABC or extragnathic GCRG.

Cytogenetic abnormalities in ABC were first reported by Panoutsakopoulos et al. in 1999, with a recurrent chromosomal translocation t(16;17)(q22;p13) being identified in two cases.[9] Subsequently, Dal Cin et al. reported two additional cases of solid and extraosseous ABC with the same translocation.[10] In 2004, Oliveira et al. (add reference) identified the fusion gene partners as CDH11 (osteoblast cadherin 11), on chromosome 16q22 and USP6 (ubiquitin protease 6, a.k.a Tre2 oncogene), on chromosome 17p13. The CDH11-USP6 fusion transcript was identified only in primary ABC, but not in secondary ABC.[11, 12] Subsequently, additional variant translocations were identified in ABC, with USP6 being the common gene partner, whose transcription being upregulated by promoter swapping with other genes, inclusing ZNF9, COL1A1, TRAP150 and OMD.[13]

As GCRG and solid ABC cannot be distinguished morphologically, we sought to investigate if USP6 genetic alterations, a hallmark of primary solid and classic ABC, are also a feature of GCRG occurring either in the gnathic or small bones of the hands and feet.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Department of Pathology files were searched for cases with the diagnoses of ‘giant cell reparative granuloma’, ‘aneurysmal bone cyst’ and ‘giant cell rich lesions’, between 2000 and 2013. The criteria for selection included availability for non-decalcified tissue suitable for FISH analysis. The clinical, radiographic and microscopic findings were reviewed. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB# WA0151-13 MSKCC).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

FISH on interphase nuclei from paraffin embedded 4-micron sections was performed applying custom probes using bacterial artificial chromosomes (BAC), covering and flanking USP6 gene (Table 1). BAC clones were chosen according to USCS genome browser (http://genome.uscs.edu) and obtained from BACPAC sources of Children’s Hospital of Oakland Research Institute (CHORI; Oakland, CA; http://bacpac.chori.org). DNA from individual BACs was isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions, labeled with different fluorochromes in a nick translation reaction, denatured, and hybridized to pretreated slides. Slides were then incubated, washed, and mounted with DAPI in an antifade solution. The genomic location of each BAC set was verified by hybridizing them to normal metaphase chromosomes. Two hundred successive nuclei were examined using a Zeiss fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan, Oberkochen, Germany), controlled by Isis 5 software (Metasystems). A positive score was interpreted when at least 20% of the nuclei showed a break-apart signal. Nuclei with incomplete set of signals were omitted from the score.

Table 1.

BAC Clones for USP6 gene.

| Clones | Cytoband | Gene | GP-S | GP-E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP11-111I16 | 17p13.2 | T-USP6 | 4824242 | 4968438 |

| RP11-81A22 | 17p13.2 | T-USP6 | 4639600 | 4838930 |

| RP11-457I18 | 17p13.2 | C-USP6 | 5152461 | 5361124 |

| RP11-107P18 | 17p13.2 | C-USP6 | 5415499 | 5602992 |

| RP11-27E24 | 17p13.2 | C-USP6 | 5621843 | 5776426 |

RESULTS

Clinical and Radiographic Features

Clinical features are summarized in Table 2. Forty-nine samples from 48 patients (26 females and 22 male patients) were selected, including 17 lesions in the GCRG study group (9 from small bone of the hands and feet and 8 from gnathic sites) and 32 lesions in the control group (15 primary ABC from the long bones, 7 primary ABC from the flat bones, 8 GCT and 2 brown tumors of hyperparathyroidism).

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic Features and FISH Results.

| Case #* | Age | Sex | Site | Diagnosis | FISH for USP6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | F | finger | GCRG / solid ABC | POS |

| 2 | 26 | M | finger | GCRG / solid ABC | POS |

| 3 | 9 | F | finger | GCRG / solid ABC | POS |

| 4 | 13 | F | calcaneus | GCRG / solid ABC | POS |

| 5 | 16 | M | calcaneus | GCRG / solid ABC | POS |

| 6 | 38 | M | finger | GCRG / ABC | POS |

| 7 | 14 | M | finger | GCRG | POS |

| 8 | 19 | F | finger | GCRG / ABC | POS |

| 9 | 16 | M | finger | GCRG | NEG |

| 10 | 36 | F | mandible | GCRG | NEG |

| 11 | 54 | F | mandible | GCRG | NEG |

| 12 | 5 | M | maxilla | GCRG | NEG |

| 13 | 13 | F | maxilla | GCRG | NEG |

| 14 | 70 | M | maxilla | GCRG | NEG |

| 15 | 45 | F | maxillary sinus | GCRG | NEG |

| 16 | 45 | F | maxillary sinus | GCRG | NEG |

| 17 | 85 | F | mandible | GCRG | NEG |

| 18 | 56 | F | femur - distal | brown tumor | NEG |

| 19 | 33 | F | mandible | brown tumor | NEG |

| 20 | 4 | M | fibula | ABC | POS |

| 21 | 17 | M | femur | ABC | NEG |

| 22 | 32 | M | femur | ABC | NEG |

| 23 | 10 | M | ulna | ABC | NEG |

| 24 | 15 | M | humerus | ABC | NEG |

| 25 | 4 | F | fibula | ABC | POS |

| 26 | 3 | F | femur | ABC | NEG |

| 27 | 21 | M | radius | ABC | POS |

| 28 | 9 | F | tibia | ABC | POS |

| 29 | 15 | F | tibia | ABC | NEG |

| 30 | 3 | F | tibia | ABC | POS |

| 31 | 24 | F | tibia | ABC | NEG |

| 32 | 29 | F | ulna | ABC | POS |

| 33 | 22 | M | fibula | ABC | NEG |

| 34 | 17 | F | radius | ABC | POS |

| 35 | 27 | F | orbit | ABC | POS |

| 36 | 18 | M | pubis | ABC | POS |

| 37 | 14 | F | manubrium | ABC | POS |

| 38 | 54 | F | temporal bone | ABC | POS |

| 39 | 14 | F | clavicle | ABC | POS |

| 40 | 18 | F | clavicle | ABC | POS |

| 41 | 14 | F | ilium | ABC | NEG |

| 42 | 33 | M | tibia | GCT with secondary ABC | NEG |

| 43 | 16 | M | tibia | GCT with secondary ABC | NEG |

| 44 | 49 | M | patella | GCT with secondary ABC | NEG |

| 45 | 38 | M | femur | GCT with secondary ABC | NEG |

| 46 | 43 | M | femur | GCT with secondary ABC | NEG |

| 47 | 19 | M | sacrum | GCT with secondary ABC | NEG |

| 48 | 36 | M | finger | GCT | NEG |

| 49 | 51 | F | finger | GCT | NEG |

GCRG, giant cell reparative granuloma; ABC, aneurysmal bone cyst; GCT, giant cell tumor; POS – positive, NEG – negative;

Shaded region represents lesions involving the bones of the hands and feet.

The GCRG involving the hands and feet occurred in 9 patients, 5 males and 4 females, with ages ranging from 9-38 years (median – 16 years of age). Seven lesions involved the digits and two involved the calcaneus. On plain radiographs, all lesions had a lytic appearance and all except one showed cortical destruction. Periosteal reaction was seen in four cases. MRI images were available in 8 of the 9 cases, which showed a size range 1.3 - 4.8 cm (mean – 2.7 cm). The lesions were purely cystic in two cases, solid in two cases and mixed cystic and solid in 4 cases. Fluid-fluid levels were seen in all except two cases and extra-osseous extension was seen in all except one case.

Gnathic GCRG included 8 lesions from 7 patients (5 females and 2 males). The age at diagnosis ranged from 5-85 years (median – 45 years old). Five lesions from 4 patients involved the maxilla and 3 involved the mandible. CT findings were available in 6 of the 7 patients and showed destructive enhancing lesions involving the bone, ranging from 1.3 to 4.5 cm, and extending into the surrounding soft tissue. One of the 6 cases showed focal cystic change. Fifteen of the 17 lesions in the GCRG study group were primary lesions and two were recurrent lesions.

The ABCs of the long bones showed no gender predilection and occurred in patients with an age distribution from 3–32 years (median – 15 years), while those with ABCs of flat bones showed a 6:1 female to male ratio, and an age range at diagnosis of 14-54 years (median – 18 years). The sites of involvement of the ABCs included tibia (4), femur (3), fibula (3), humerus (1), ulna (2), radius (2), clavicle (2), orbit (1), pubis (1), manubrium (1), temporal bone (1) and iliac bone (1). Radiographically, most ABCs were composed of lytic, expansile masses with well-defined borders. MRI imaging highlighted the characteristic internal septa and fluid-fluid levels. The patients with GCT showed a male predilection, an age range at diagnosis of 16–51 years (median – 37 years), occurring in the femur (2), tibia (2), finger (2), patella (1) and sacrum (1). Radiographically, GCT showed an expansile growth, commonly involving the epi-metaphysis and occasionally extending into surrounding soft tissues. The two brown tumors occurring in the setting of documented hyperparathyroidism involved the mandible and the femur. Radiographically, both patients presented with multiple osseous lytic, expansile lesions involving the ribs and other long bones.

Pathologic Findings

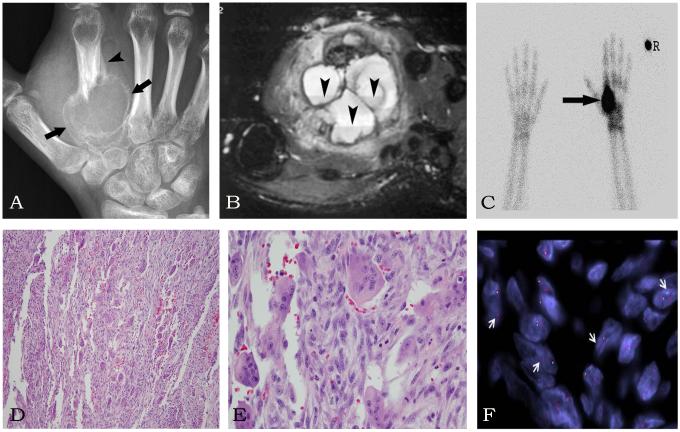

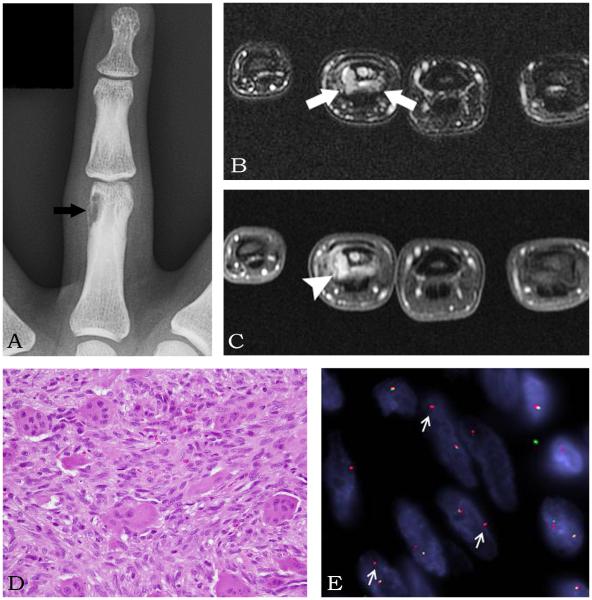

The GCRG occurring in the hands, feet or gnathic location shared with the two brown tumors an osteoclast-type giant cell-rich morphology associated with a spindle cell component within a variable fibrous stroma. Areas of hemorrhage and cyst formation were frequently noted. Few lesions showed reactive new bone formation. (Figures 1 and 2) No cytologic atypia or increased mitotic activity was noted.

Figure 1.

GCRG of second metacarpal bone in a 16 year-old-female (Case 1). The Anterior-Posterior (AP) radiograph (A) shows an expansile lytic lesion (arrows) with a Codman’s triangle (arrowhead) in a second metacarpal bone. (B) The MRI axial STIR image of the hand shows multiple fluid levels (arrowheads) in the expansile second metacarpal lesion mimicking an ABC. (C) The spot view of the bone scan shows intense radiotracer uptake (arrow) in the second metacarpal bone. (R – right) (D) H&E sections showing a giant cell-rich lesion (100x) which at higher power (E, 200x) reveals a mixture of bland spindle cells and osteoclast-like giant cells. (F) FISH for USP6 gene break-apart assay showing an unbalanced rearrangement (arrows) with deletion of the telomeric (green) signal. (red – centromeric signal)

Figure 2.

GCRG in the 4th proximal phalanx of a 38 year-old-male (Case 6). (A) Anterior-Posterior radiograph of the 4th finger shows an eccentric lesion (arrow) in the proximal phalanx. (B) MRI axial STIR image shows the lesion (arrows) eroding the bone. (C) MRI axial T1-weighted image shows an enhancing lesion (arrowhead) eroding the bone. (D) H&E section (200x) reveals lesional spindle cells with admixed osteoclast-like giant cells. (E) FISH showing an USP6 split apart signal (arrows) with associated deletion of the telomeric (green) signal. (red – centromeric signal)

The ABC lesions of the long and flat bones showed distinctive cystic hemorrhagic areas, with fibrous cyst walls composed of spindle to histiocytoid cells admixed with osteoclast-like giant cells and variable osteoid matrix deposition. Few lesions showed focally more solid areas, with morphology indistinguishable from the GCRGs.

The GCTs showed a uniform distribution of giant cells in a background of mononuclear cells. Areas of hemorrhage were frequently noted. Six of the eight cases showed presence of a secondary ABC component.

FISH Findings

FISH for USP6 was performed on all 49 cases in the study. (Table 2) Eight of the 9 (89%) lesions of the hand and feet showed rearrangements of the USP6 gene. (Figure 1 and 2) In contrast, none of the 8 gnathic GCRGs showed USP6 gene abnormalities. From the control group, USP6 gene rearrangements were identified in 13/22 (59%) ABCs from the long and flat bones. No gene abnormalities were identified in any of the brown tumors or the GCT of bone with or without secondary ABC changes. The pattern of USP6 gene abnormalities was similar in the lesions of the hands and feet and the primary ABCs from long and flat bones with the genetic abnormalities seen only in the spindle cells and not in the osteoclast-like giant cells.

DISCUSSION

The recent identification of recurrent chromosomal translocations involving USP6 gene in primary ABC has changed our understanding of this disease, from a a reactive, non-neoplastic process, possibly initiated by injury to the capillary network leading to an expansile destructive process, to a clonal, truly neoplastic lesion. The solid variant of ABC has been shown to harbour similar gentic events as the classic cystic lesions.

USP6 is a ubiquitin-specific protease, the gene of which has been localized to the short arm of chromosome 17 (17p13). The gene has been postulated to contribute to hominoid speciation.[14] The oncogenic mechanism by which USP6 –related gene fusion is involved is tumorigenesis, as studied in ABCs, is by promoter swapping wherein the juxtaposition of USP6 gene to a highly active CDH11 promoter leads to USP6 upregulation.[11] Apart from the bone lesions such as ABCs, other lesions wherein USP6 has been implicated in the pathogenesis include nodular fasciitis and a subset of myositis ossificans. [15, 16] Interestingly, both of these tumors have for long been reagarded as reactive lesions in the soft tissue.

The terminology related to the giant cell-rich lesions of the hands and feet has been long controversial, with designations including both GCRG and solid ABC, due to their signficant morphologic overlap. Given that ABC is a clonal process and GCRGs have always been considered a reactive, non-neoplastic process involving gnathic and extra-gnathic locations, the combined terminology of GCRG/solid ABC is ambiguous and does not shed light on the true biologic nature of the lesion. Furthermore, the morphologic similarities between gnathic and extragnathic GCRGs raise the question if lesions occuring at different sites share similar genetic alterations and biologic potential. In an attempt to address these issues, we investigated a series of lesions of the gnathic GCRGs and giant cell rich lesions of hands and feet in comparison with primary ABCs and giant cell tumors of long bones.

None of the 8 gnathic GCRGs in our study showed USP6 abnormalities. In contrast, eight of the 9 lesions from hands and feet showed rearrangements of the USP6 gene. These results indicate that the two groups have different genetic abnormalities, and that the so-called GCRG of the small bones of hands and feet are true neoplastic processes, in keeping with ABC. Thus we recommend that the terminology of GCRG of the hands and feet should be abandoned and replaced instead with either ABC or solid variant of ABC depending on the radiologic findings.

Our study also confirms that gnathic lesions are pathogentically different from the those occuring in extra-gnathic locations, even though they share significant morphologic overlap. The terminology of GCRG should be reserved mainly for lesions occuring in the gnathic location. USP6 rearrangements were identified in 59% of the ABCs in our study. This is in keeping with the reported rates of USP6 rearrangement (69%) as reported in the literature.[12] None of the GCT of bone showed USP6 rearrangements.

Brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism is a bone lesion occuring in the setting of primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism. Radiographically, these are lytic lesions. Histologically, they show giant cell rich areas with associated fibrosis and new bone formation and are indistinguishable form other giant cell-rich lesions such as solid ABC, GCRG or GCT of bone. Clinical history along with serum calcium, phosphorous and parathormone leves help in diagnosis of these lesions. None of the two cases in our study showed USP6 gene abnormalities, findings in keeping with the study by Sukov et al. who showed absence of USP6 abnormalities in 6 cases of brown tumors.[16]

In summary, most of the so-called GCRG of the hands and feet are truly solid ABCs and should be classified as such. In our opinion, the terminology of GCRG should be restricted to the gnathic lesions with this morphology and should be avoided in extra-gnathic sites. Our study also validates the usefulness of FISH analysis for USP6 gene rearrangements as an ancillary tool to separate ABCs from other giant cell rich lesions such as GCRG and giant cell tumor of bone, especially in the setting of lesions in small bones where it may difficult to distinguish these entities based on clinical, radiologic and morphologic findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lorraine Biedrzycki for preparation of composite figures and Milagros Soto for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE / CONFLICT OF INTEREST: None

REFERENCES

- [1].Jaffe HL. Giant-cell reparative granuloma, traumatic bone cyst, and fibrous (fibro-oseous) dysplasia of the jawbones. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1953;6:159–175. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(53)90151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ackerman LV, Spjut HJ. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Washington D.C.: 1962. Tumors of bone and cartilage. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lorenzo JC, Dorfman HD. Giant-cell reparative granuloma of short tubular bones of the hands and feet. The American journal of surgical pathology. 1980;4:551–563. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sanerkin NG, Mott MG, Roylance J. An unusual intraosseous lesion with fibroblastic, osteoclastic, osteoblastic, aneurysmal and fibromyxoid elements. "Solid" variant of aneurysmal bone cyst. Cancer. 1983;51:2278–2286. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830615)51:12<2278::aid-cncr2820511219>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ratner V, Dorfman HD. Giant-cell reparative granuloma of the hand and foot bones. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1990:251–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bertoni F, Bacchini P, Capanna R, Ruggieri P, Biagini R, Ferruzzi A, Bettelli G, Picci P, Campanacci M. Solid variant of aneurysmal bone cyst. Cancer. 1993;71:729–734. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3<729::aid-cncr2820710313>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Oda Y, Tsuneyoshi M, Shinohara N. "Solid" variant of aneurysmal bone cyst (extragnathic giant cell reparative granuloma) in the axial skeleton and long bones. A study of its morphologic spectrum and distinction from allied giant cell lesions. Cancer. 1992;70:2642–2649. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921201)70:11<2642::aid-cncr2820701113>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ilaslan H, Sundaram M, Unni KK. Solid variant of aneurysmal bone cysts in long tubular bones: giant cell reparative granuloma. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2003;180:1681–1687. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.6.1801681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Panoutsakopoulos G, Pandis N, Kyriazoglou I, Gustafson P, Mertens F, Mandahl N. Recurrent t(16;17)(q22;p13) in aneurysmal bone cysts. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 1999;26:265–266. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199911)26:3<265::aid-gcc12>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dal Cin P, Kozakewich HP, Goumnerova L, Mankin HJ, Rosenberg AE, Fletcher JA. Variant translocations involving 16q22 and 17p13 in solid variant and extraosseous forms of aneurysmal bone cyst. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 2000;28:233–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Oliveira AM, Hsi BL, Weremowicz S, Rosenberg AE, Dal Cin P, Joseph N, Bridge JA, Perez-Atayde AR, Fletcher JA. USP6 (Tre2) fusion oncogenes in aneurysmal bone cyst. Cancer research. 2004;64:1920–1923. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Oliveira AM, Perez-Atayde AR, Inwards CY, Medeiros F, Derr V, Hsi BL, Gebhardt MC, Rosenberg AE, Fletcher JA. USP6 and CDH11 oncogenes identify the neoplastic cell in primary aneurysmal bone cysts and are absent in so-called secondary aneurysmal bone cysts. The American journal of pathology. 2004;165:1773–1780. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63432-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Oliveira AM, Perez-Atayde AR, Dal Cin P, Gebhardt MC, Chen CJ, Neff JR, Demetri GD, Rosenberg AE, Bridge JA, Fletcher JA. Aneurysmal bone cyst variant translocations upregulate USP6 transcription by promoter swapping with the ZNF9, COL1A1, TRAP150, and OMD genes. Oncogene. 2005;24:3419–3426. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Paulding CA, Ruvolo M, Haber DA. The Tre2 (USP6) oncogene is a hominoid-specific gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:2507–2511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437015100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, Roth CW, Seys AR, Jin L, Ye Y, Lau AW, Wang X, Oliveira AM. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2011;91:1427–1433. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sukov WR, Franco MF, Erickson-Johnson M, Chou MM, Unni KK, Wenger DE, Wang X, Oliveira AM. Frequency of USP6 rearrangements in myositis ossificans, brown tumor, and cherubism: molecular cytogenetic evidence that a subset of "myositis ossificans-like lesions" are the early phases in the formation of soft-tissue aneurysmal bone cyst. Skeletal radiology. 2008;37:321–327. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0442-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]