Abstract

Adaptive immune responses to inhaled allergens are induced following CCR7-dependent migration of pre-DC (precursor of DC)-derived conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) from the lung to regional lymph nodes (LN). However, monocyte-derived (mo) DCs in the lung express very low levels of Ccr7, and consequently do not migrate efficiently to LN. To investigate the molecular mechanisms that underlie this dichotomy, we studied epigenetic modifications at the Ccr7 locus of murine cDCs and moDCs. When expanded from bone marrow precursors, moDCs were enriched at the Ccr7 locus for trimethylation of histone 3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3), a modification associated with transcriptional repression. Similarly, moDCs prepared from the lung also displayed increased levels of H3K27me3 at the Ccr7 promoter compared with migratory cDCs from that organ. Analysis of DC progenitors revealed that epigenetic modification of Ccr7 does not occur early during DC lineage commitment because monocytes and pre-DCs both had low levels of Ccr7-associated H3K27me3. Rather, Ccr7 is gradually silenced during the differentiation of monocytes to moDCs. Thus, epigenetic modifications of the Ccr7 locus control the migration, and therefore the function of DCs in vivo. These findings suggest that manipulating epigenetic mechanisms might be a novel approach to control DC migration and thereby improve DC-based vaccines and treat inflammatory diseases of the lung.

INTRODUCTION

The migration of lung DCs to lymph nodes (LN) is critical for orchestrating adaptive immune responses against inhaled antigens or microbes (1–4). Mobilization of lung DCs to LN is dependent on the chemokine receptor CCR7 and its ligands, CCL19 and CCL21, which are produced in afferent lymphatic vessels and the T cell zones of LN (5). Under homeostatic conditions, CCR7-dependent migration of lung DCs to draining LN is important for the induction of regulatory T cells, which help maintain peripheral tolerance to innocuous environmental antigens (6). During infection or other inflammatory insults, migratory DCs become licensed to induce cytotoxic T cells or effector T helper cell differentiation (7). These effector T cells not only assist with pathogen clearance, but can also mediate maladaptive immune responses leading to inflammatory lung diseases such as asthma (3, 4, 8). Because migratory DCs play a central role in shaping immune responses in the lungs, manipulating Ccr7 expression is a potential strategy for either augmenting or suppressing adaptive immunity. However, such a strategy requires an improved understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible for regulating Ccr7 expression.

As in other nonlymphoid tissues, DCs in the lungs are comprised of two major lineages: conventional DCs (cDCs) and monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs)(9, 10). Lung cDCs arise from circulating progenitor cells referred to as pre-DCs (precursor of DCs), which descend from the common DC progenitor in the bone marrow (BM) via a pathway dependent upon Flt3 ligand (Flt3L) (11). In contrast, lung resident moDCs develop from emigrating peripheral blood monocytes independently of Flt3L (10). There is growing evidence that DC functional specialization is dependent upon their developmental lineage (12). In agreement with this, we recently reported that lung cDCs and moDCs differ significantly in their ability to express Ccr7 and migrate to regional LN (10). During steady-state conditions, Ccr7 is expressed at low levels in lung cDCs and is markedly up-regulated by microbial products, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid (poly I:C). By contrast, moDCs in the lung fail to express Ccr7, even after treatment with these microbial products. Consequently, cDCs, but not moDCs can efficiently ferry antigen from the lung to regional LN. These findings are in agreement with studies showing that moDCs from other peripheral tissues, such as the skin and gut, also express low levels of Ccr7 and migrate poorly to LN (13, 14). Taken together, these studies suggest that the capacity for peripheral DCs to express Ccr7 and migrate to LN is regulated in a lineage-specific manner.

The unique transcriptional profiles of DC subsets are likely important for dictating their functional and migratory properties. While the transcriptomes of DC subsets are clearly dependent upon lineage-specific transcription factors (15), epigenetic mechanisms are also essential for regulating gene expression during DC development (16). Epigenetic mechanisms, which include DNA methylation and posttranslational modifications of histone tails, regulate gene expression by governing chromatin accessibility to the transcriptional machinery (17). Although epigenetic modifications of multiple genes have been well-studied in the context of T helper cell differentiation (18–20), remarkably little is known of epigenetic mechanisms that might be expected to influence DC development or function (16). In the present study, we investigated whether epigenetic modifications at the Ccr7 locus influence the migratory properties of different DC subsets. We found that moDCs have increased repressive histone modifications at the Ccr7 locus, which was associated with decreased Ccr7 expression and a nonmigratory phenotype. Surprisingly, these repressive epigenetic marks are not established during lineage commitment within the BM, but rather during monocyte differentiation into moDCs in peripheral tissues. Our findings suggest that epigenetic modifications at the Ccr7 locus closely correlate with the migratory properties, and hence the functional roles, of nonlymphoid DC subsets. The transcriptional silencing of Ccr7 during moDC differentiation might also have implications for the development of effective DC-based vaccines for immunotherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6Jand OT-II (C57BL/6-Tg (TcraTcrb) 425Cbn/J) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Ccr7gfp reporter mice were generated in our laboratory and have been previously described (10). Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and used between 6 and 12 weeks of age in accordance with guidelines provided by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were incubated with a non-specific-binding blocking reagent cocktail of anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (2.4G2), and normal mouse and rat serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 5 min. For staining of surface antigens, cells were incubated with fluorochrome (Allophycocyanin (APC), APC-Cy7, Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 647, eFluor 450, eFluor 605 NC, FITC, PerCP-Cy5.5 or Phycoerythrin), or biotin-conjugated antibodies against mouse CD3ε (145-2C11), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (N418), CD14 (Sa2-8), CD19 (6D5), CD40 (1C10), CD49b (DX5), CD86 (GL1), CD88 (20/70), CD103 (M290), CD115 (AFS98), CD135 (A2F10), F4/80 (BM8), Ly-6C (AL-21), Ly-6G (1A8), MHC class II I-Ab (AFb.120), Sca-1 (D7), and TER-119 (BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA), BioLegend (San Diego, CA) and eBioscience (San Diego, CA)). Staining with biotinylated antibodies was followed by fluorochrome-conjugated streptavidin. Stained cells were analyzed on a 5 laser LSRII (BD Biosciences), or sorted on a 5 laser ARIA-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and the data analyzed using FACS Diva (BD Bioscience) and FlowJo (Treestar, Ashland, OR) software. Dead cells were excluded based on their forward and side scatter or uptake of 7-AAD. Only single cells were analyzed.

Generation and analysis of BM-elicited DCs

Marrow was collected from pulverized bones, and RBCs were lysed with 0.15 M ammonium chloride and 1 mM potassium bicarbonate. BM cells were then cultured in complete RPMI media (RPMI 1640, 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini, West Sacramento, CA), penicillin/streptomycin and 50 ng ml−1 β-mercaptoethanol) supplemented with either 100 ng ml−1 recombinant human Flt3L to generate FL-DCs; or 5 ng ml−1 GM-CSF and IL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) to generate GM-DCs. Recombinant human Flt3L was produced by the NIEHS Protein Expression Core Facility using previously described methods (21). Media was replaced every three days, at which time fresh cytokines were also added. In some experiments 100 ng ml−1 of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or 10 μg ml−1poly (I:C) (Invivogen, San Diego, CA) was added during the last 24 hours of culture to induce DC maturation. Cells were harvested on day 8 and stained with biotinylated anti-CD11c antibody (eBioscience) followed by incubation with streptavidin Microbeads (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA), and finally isolated with an automated magnet-activated cell sorter (MACS) to a purity of >90% CD11c+ cells. To assay T cell stimulating activity, BM-derived DCs were purified using MACS, and then cultured with naïve CD4+ OT-II cells (DC:T cell ratio = 1:2) in the presence of 10 nM OVA323–339 peptide (New England Peptide, Gardner, MA) as previously described (8). Proliferation was inferred from recovery of viable (trypan blue negative) T cells after 5 days of coculture. In some experiments, DCs were centrifuged onto glass slides and photographed using an Olympus BX51 microscope, DP70 digital camera, and DP software (Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

Preparation and analysis of lung DCs subsets

Lung DC subsets were isolated and purified by flow cytometry-based sorting as previously described (22). To induce activation of lung DCs in vivo, mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and given 0.1 μg LPS by oropharyngeal aspiration 16 hours prior to lung DC isolation. In some experiments, purified DC subsets were cultured in complete RPMI media containing 100 ng ml−1 LPS.

Purification of monocytes and pre-DCs from BM

Ly-6Chi monocytes (CD3− CD11b+CD11c− CD19− CD49b− CD115+F4/80hiI-A− Ly-6ChiLy-6G− Sca-1− TER119−) or pre-DCs (CD3− CD11b− CD11c+CD19− CD49b− I-A− CD135+Ly-6G− Sca-1− TER119−) from BM were enriched by MACS and then further purified by flow cytometry-based sorting. In some experiments, Ly-6Chi monocytes were cultured in complete RPMI media supplemented with 5 ng ml−1 GM-CSF and IL-4 to generate monocyte-derived DCs. Culture media was changed every three days with fresh cytokines added at that time.

Chemotaxis assays

LPS-matured, CD11c+ BM-elicited DCs (2 × 105) were added to the upper chamber of a Transwell® insert (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) with a 5 μm polycarbonate membrane. Various concentrations of CCL19 (R&D) were added to the bottom chamber. After a 2 hour incubation at 37°C, migrated cells were collected from the bottom chamber and enumerated by flow cytometry using Accucount Beads (Spherotech, Lake Forest, IL) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

cDNA amplification and analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells using an RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) or TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) and converted to cDNA with oligo dT and random hexamer primers using MuLV reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). PCR amplification was performed using primers listed in Supplemental Table 1 with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies) and an Mx3000P quantitative PCR (QPCR) system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The efficiency-corrected ΔCt for each gene was determined and normalized to Gapdh expression.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Native chromatin was prepared from cells by small scale micrococcal nuclease digestion as previously described with modification (23). Briefly, CD11c+ BM-elicited DCs (4 × 106) or sorted lung DCs (0.2–1 × 106) were washed and incubated in lysis buffer containing 0.4% NP40 for 10 minutes on ice. Nuclei were then washed and resuspended in digestion buffer containing 25 U/ml micrococcal nuclease (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ) and incubated at 37°C for 5 min to generate mono- and di-nucleosomes. The reaction was stopped by addition of 10 mM Tris-HCl pH8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM sodium butyrate, and samples were incubated overnight at 4°C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was harvested and Triton X 100 was added to a concentration of 1% (vol/vol). For BM-elicited DC samples, chromatin was pre-cleared with protein A-Sepharose / salmon sperm DNA (EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with 2.5 μg of either anti-trimethylated H3 lysine 27 (anti-H3K27me3, Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA), anti-acetylated H3 lysine 27 (anti-H3K27ac, Active Motif), or nonspecific anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX). After incubation with Protein A-Sepharose / salmon sperm DNA for 1 hour, immunoprecipitates were washed vigorously and DNA was purified. For lung DC samples, chromatin was immunoprecipitated with the above antibodies using the MAGnify™ ChIP System (Life Technologies) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Bound and input fractions were quantified by QPCR using an MxP3000p QPCR system (Agilent Technologies) with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies) and PCR primers listed in Supplemental Table 1. PCR reaction conditions were as follows: 10 min at 95°C; 15 sec at 95°C and 60 sec at 62°C for 40 cycles; and dissociation curve analysis to verify specific PCR product labelling. Analysis was performed using the efficiency-corrected ΔCt method, with amplification efficiency determined from a standard curve that was generated from genomic DNA. Data are presented as the signal from bound fractions normalized to the input fraction.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) or standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) as indicated. Statistical differences between groups were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test, unless indicated otherwise. P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

BM-elicited conventional DCs, but not monocyte-derived DCs, express functional CCR7

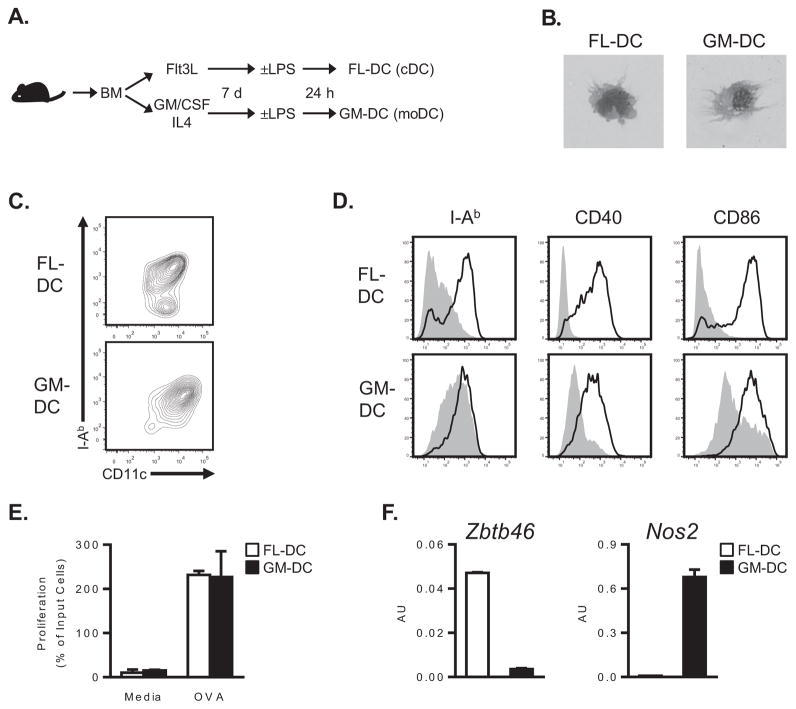

Lung DCs are rare compared to many other cell types in that organ. Accordingly, we first used different culture conditions to generate cDCs and moDCs from BM progenitors ex vivo (Figure 1A)(24). Because Flt3L is required for cDC development, we cultured BM progenitors in the presence of this cytokine to generate cDCs (FL-DCs). To generate moDCs, we cultured progenitors with GM-CSF and IL-4 (GM-DCs). Light microscopic and flow cytometric analyses revealed that both cultures contained CD11chiI-AbhiDCs having similar morphologies, including the presence of dendrites (Figures 1B–C). FL-DCs and GM-DCs were similarly responsive to maturation stimuli, as both up-regulated expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules following LPS treatment (Figure 1D). Furthermore, LPS treatment induced similar expression of Il6 and Il12b mRNA in FL-DCs and GM-DCs (data not shown). Importantly, LPS-matured FL-DCs and GM-DCs were equivalent in their ability to stimulate naïve T cells (Figure 1E). Thus, by these standard assays, FL-DCs and GM-DCs each displayed the characteristics of bona fide DCs. However, FL-DCs and GM-DCs differed considerably with regard to lineage-associated gene expression. Compared to GM-DCs, FL-DCs expressed significantly higher levels of mRNA for the cDC-specific transcription factor Zbtb46 (25, 26) (Figure 1F). In contrast, activated GM-DCs highly expressed Nos2, consistent with a moDC phenotype (27) (Figure 1F). Based on these observations, we concluded that FL-DCs and GM-DCs corresponded to cDCs and moDCs, respectively.

Figure 1. Culturing BM precursors with Flt3L or GM-CSF/IL-4 yields DCs that resemble conventional or monocyte-derived DCs, respectively.

(A) Schematic protocol for the generation and maturation of BM-elicited DCs using Flt3L (FL-DCs) or GM-CSF/IL-4 (GM-DCs). (B) Representative light micrographs of cytospin preparations of FL- or GM-DCs. (C) Representative cytograms depicting surface I-Ab and CD11c expression on FL- and GM-DCs after maturation with LPS. (D) Histograms depicting I-Ab, CD40 and CD86 expression on unstimulated (shaded histograms) or LPS-matured (bold lines) DCs. Data are from a single experiment, representative of two. (E) Stimulation of naïve CD4+ OT-II cells by LPS-matured FL- or GM-DCs in the presence or absence of OVA323–339 peptide. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.d. of viable T cells (duplicate samples). Data are from a single experiment, representative of two. (F) Zbtb46 and Nos2 mRNA expression by MACS-purified CD11c+ FL- and GM-DCs. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.d. of RNA amounts in arbitrary units (AU) after normalization to Gapdh mRNA. Data are from a single experiment, representative of two.

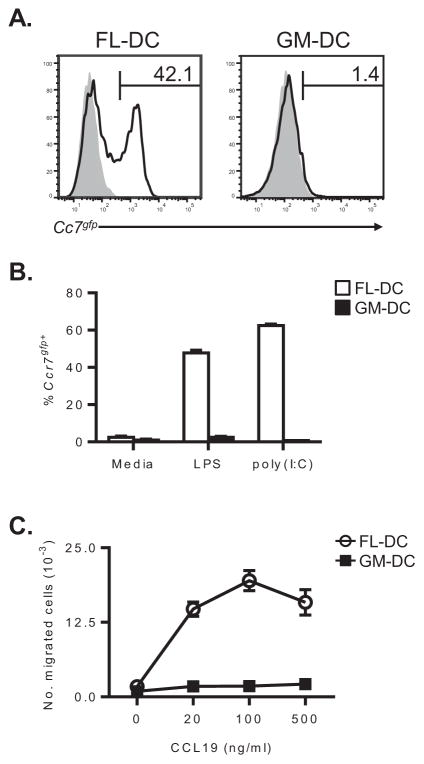

Ccr7gfp reporter mice are a convenient resource for assaying Ccr7 expression in DCs (10). Using these mice as a source of BM, we compared Ccr7gfp expression in FL-DCs and GM-DCs. Following LPS stimulation, FL-DCs rapidly up-regulated Ccr7gfp (Figure 2A–B). In contrast, GM-DCs expressed very low levels of Ccr7gfp following LPS treatment (Figure 2A–B). Similar results were observed when FL-DCs and GM-DCs were stimulated with the TLR3 ligand poly (I:C) (Figure 2B). To confirm that the GFP fluorescence correlated with functional CCR7 protein, we studied the abilities of FL-DCs and GM-DCs to undergo chemotaxis in response to CCL19. FL-DCs migrated very efficiently to various concentrations ofCCL19, confirming that they expressed functional CCR7 (Figure 2C). Conversely, GM-DCs migrated poorly to CCL19 (Figure 2C), which was consistent with their low expression of Ccr7gfp. Thus, although FL-DCs and GM-DCs were similar in many measures of DC function, only FL-DCs expressed functional CCR7 at high levels.

Figure 2. BM-elicited cDCs, but not moDCs, express functional CCR7.

(A) Analysis of Ccr7gfp fluorescence in CD11c+ FL- or GM-DCs generated from wild type (gray histograms) or Ccr7gfp reporter mice (bold lines) after LPS maturation. The percentage of cells expressing Ccr7gfp is indicated on each plot. (B) Comparison of Ccr7gfp expression by CD11c+ FL- or GM-DCs after stimulation with either media alone, 100 ng ml−1 LPS or 10 μg ml−1 poly (I:C) for 24 hours. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.d. of duplicate samples. Data are from a single experiment, representative of two. (C) Chemotaxis of LPS-matured FL- or GM-DCs in response to the indicated concentrations of the CCR7 ligand, CCL19. Symbols represent the mean ± s.d. of duplicate samples. Data are from a single experiment, representative of three.

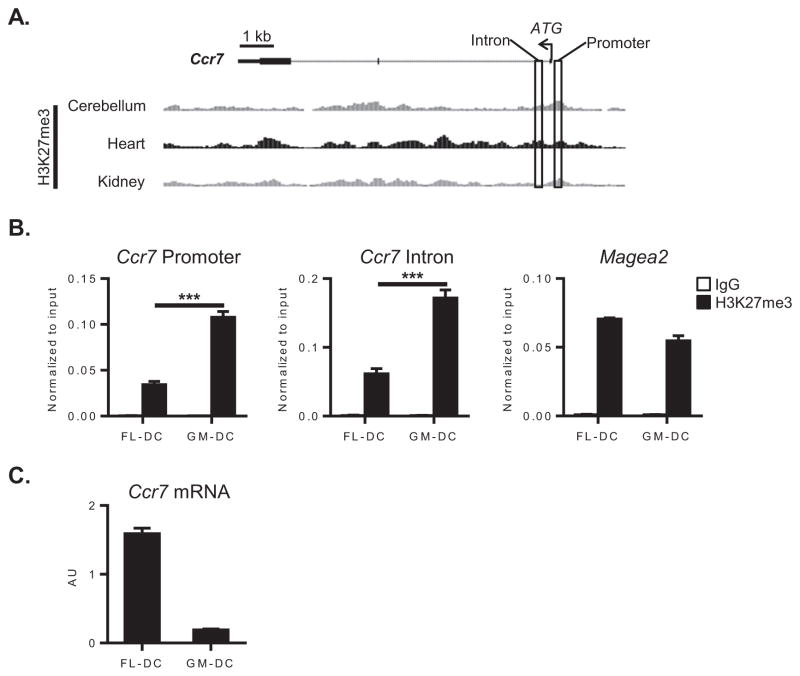

The Ccr7 locus is enriched for repressive histone modifications in BM-elicited moDCs

The inability of GM-DCs to express Ccr7 despite having otherwise normal responsiveness to LPS (Figure 1D) suggested that the Ccr7 locus in these cells might be inaccessible to transcriptional activators. It is well established that histone modifications help govern chromatin accessibility to the transcriptional machinery, thereby regulating gene expression (17). In particular, trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone 3 (H3K27me3), which is primarily mediated by the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), is associated with transcriptional repression in various cells including DCs and macrophages (28, 29). Analysis of available ChIP-sequencing data obtained from the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project (30) revealed that the Ccr7 promoter is enriched for H3K27me3 in tissues that generally lack CCR7 expression (Figure 3A), suggesting that H3K27me3 might also be associated with Ccr7 repression in moDCs. Therefore, using ChIP-QPCR assays, we investigated H3K27me3 modifications at the Ccr7 promoter in LPS-stimulated FL-DCs and GM-DCs. We found that the Ccr7 promoter is significantly enriched for H3K27me3 in GM-DCs, but not FL-DCs (Figure 3B). GM-DCs also had similar enrichment of H3K27me3 at the first intron of Ccr7. To exclude the possibility that our findings at the Ccr7 locus were due to a widespread, non-specific increase in H3K27me3 in GM-DCs, we studied a distant locus containing the Magea2 gene. No significant differences were seen in H3K27me3 at that locus, indicating that repressive histone marks were preferentially increased at the Ccr7 locus (Figure 3B). The level of H3K27me3 at the Ccr7 promoter was inversely related to Ccr7 mRNA expression, consistent with transcriptional repression of Ccr7 (Figure 3C). Similar differences in Ccr7-associated H3K27me3 were observed in unstimulated DCs, indicating that the repressive histone marks were established prior to DC activation (Supplemental Figure 1A). Because histone acetylation has been associated with transcriptional activation in human dendritic cells (28), we also analyzed H3K27 acetylation at the Ccr7 locus. We did not find significant differences in Ccr7-associated H3K27 acetylation between FL- and GM-DCs (Supplemental Figure 1B), suggesting that Ccr7 expression was predominantly regulated by repressive histone marks. Taken together, these findings suggest that lineage-specific repressive histone modifications help govern Ccr7 expression in BM-elicited DCs.

Figure 3. The Ccr7 locus is enriched for repressive histone modifications in BM-elicited moDCs.

(A) Structure of the Ccr7 locus, including relative amounts of H3K27me3 in chromatin from the indicated organs of adult C57BL/6 mice (available through the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project and analyzed using the UCSC Genome Browser website). The location of primers designed to amplify the Ccr7 promoter and first intron are indicated by rectangles. (B) ChIP-QPCR analysis of the Ccr7 promoter, Ccr7 first intron, or Magea2 locus in LPS-matured FL- or GM-DCs following immunoprecipitation with either anti-H3K27me3 (black bars) or nonspecific IgG (white bars) antibodies. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.d of triplicate samples after normalization to input DNA. Data are from a single experiment, representative of two. (C) Ccr7 mRNA in mature FL- or GM-DCs. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.d. of duplicate samples after normalization to Gapdh mRNA. Data are from a single experiment, representative of two. AU, arbitrary units. ***P<0.001.

Nonmigratory lung-resident moDCs have increased levels of Ccr7-associated H3K27me3

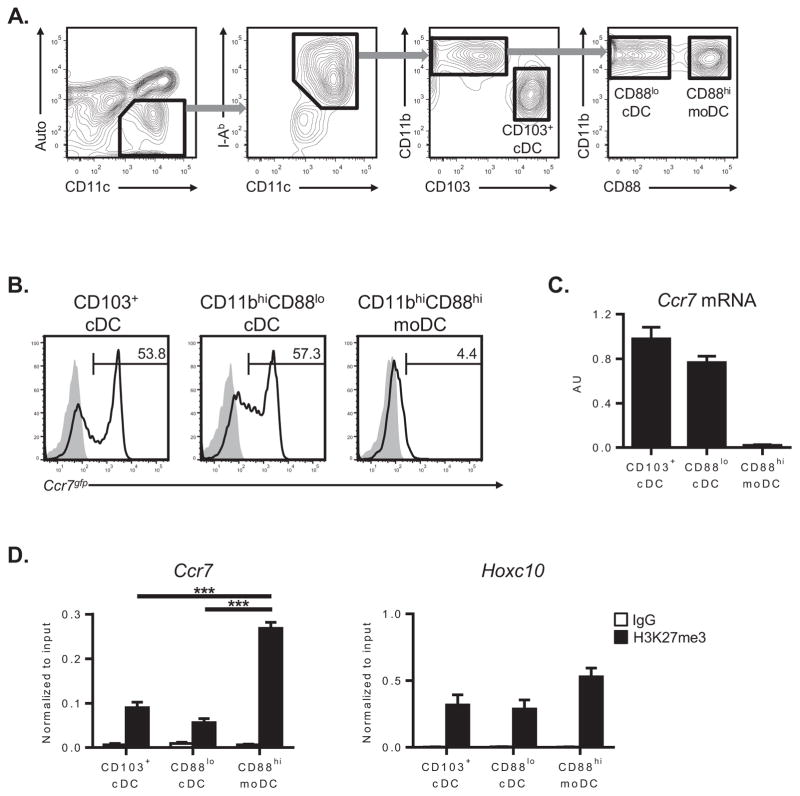

Having established that the Ccr7 locus is associated with repressive histone marks in moDCs expanded from BM progenitors, we next investigated if similar repressive histone marks are associated with Ccr7 in lung-resident moDCs. Lung-resident DCs can be phenotypically divided into CD103+or CD11bhi DCs. CD103+ DCs arise from pre-DC precursors and thus represent a pure population of cDCs (10). By contrast, CD11bhi DCs contain a mixture of Flt3L-dependentc DCs and Flt3L-independent moDCs, with the latter cells having a higher display level of CD14 (10). However, because some CD11bhi DCs express intermediate levels of CD14, this molecule cannot reliably distinguish cDCs from moDCs. CD64 expression is reported to discriminate between cDCs and moDCs (3, 31), but we recently found that display levels of a different marker, CD88, is a more reliable marker to distinguish CD11bhi moDCs fromCD11bhi cDCs (Nakano et al., submitted). To confirm that CD88can also distinguish nonmigratory moDCs from migratory cDCs, we isolated lung-resident DCs from Ccr7gfp reporter mice by flow cytometric cell sorting (Figure 4A). As expected, all lung-resident DC subsets expressed low levels of Ccr7gfp immediately after isolation from naïve mice (Figure 4B). Stimulation with LPS resulted in significant induction of Ccr7gfp in CD103+ and CD11bhiCD88loDCs (Figure 4B). In contrast, CD11bhiCD88hiDCs expressed very low levels of Ccr7gfp after activation, which is consistent with their monocytic lineage (Figure 4B). All lung DC subsets expressed high levels of CD86 after LPS stimulation (data not shown), indicating normal responsiveness to TLR4 ligands. Analysis of Ccr7 mRNA in wild type mice confirmed that this gene is more highly expressed in activated CD103+ cDCs and CD11bhiCD88locDCs compared with CD11bhiCD88hi moDCs (Figure 4C). Thus, CD88 display can identify nonmigratory, CD11bhimoDCs in the lung.

Figure 4. Nonmigratory lung-resident moDCs have increased levels of Ccr7-associated H3K27me3.

(A) Gating strategy for flow cytometry-based sorting of lung-resident DC subsets from wild type or Ccr7gfp reporter mice. (B) Analysis of Ccr7gfp expression on sorted lung-resident DCs before (shaded histograms) or after (bold lines) ex vivo stimulation with 100 ng ml−1 LPS for 24 hours. Data are from a single experiment, representative of two. (C) Ccr7 mRNA expression in lung-resident DCs isolated from mice 16 hours post-LPS inhalation. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.e.m. (after normalization to Gapdh mRNA) of combined data from two independent experiments. (D) ChIP-QPCR analysis of the Ccr7 promoter or Hoxc10 locus (reference gene) in lung-resident DCs after immunoprecipitation with either anti-H3K27me3 (black bars) or nonspecific IgG (white bars) antibodies. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.e.m (after normalization to input DNA) of combined data from three independent experiments. Auto, autofluorescence; AU, arbitrary units. ***P<0.001.

Using CD88 as a marker for moDCs, we purified migratory CD103+and CD11bhiCD88locDCs, as well as nonmigratory CD11bhiCD88himoDCs, from the lungs of LPS-treated mice. Chromatin was prepared from each DC subset and analyzed for Ccr7-associated H3K27me3. Compared to CD103+DCs and CD11bhiCD88locDCs, CD11bhiCD88hi moDCs had significantly elevated levels of H3K27me3 at the Ccr7 promoter (Figure 4D). The amount of Ccr7-associated H3K27me3 was inversely related to the expression of this gene, consistent with transcriptional silencing of Ccr7 in CD11bhiCD88hi moDCs (Figure 4C). Levels of H3K27me3 at a distant locus (Hoxc10) were similar among all DC subsets, confirming that the epigenetic differences seen at the Ccr7 promoter are not due to a nonspecific, genome-wide increase of H3K27me3 in lung moDCs (Figure 4D). Overall, these findings indicate that the nonmigratory status of lung-resident moDCs is associated with repressive histone modifications at the Ccr7 promoter.

BM monocytes have low levels of Ccr7-associated H3K27me3

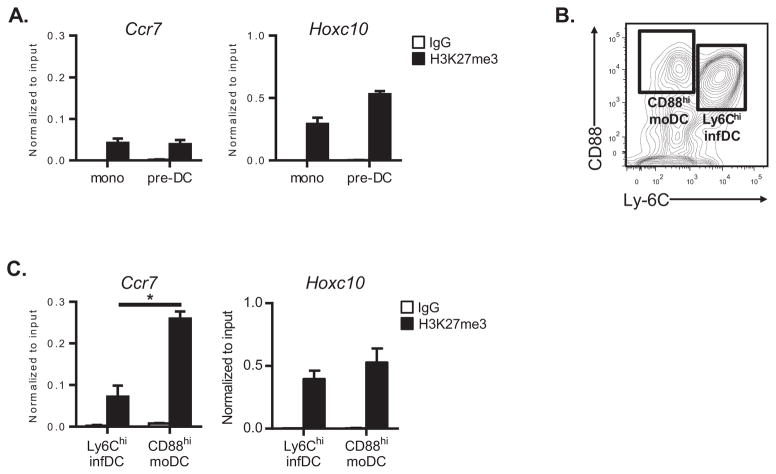

Our observation that cDCs and moDCs have disparate levels of Ccr7-associated H3K27me3 is consistent with lineage-specific epigenetic repression of Ccr7 expression. This prompted us to investigate whether the divergence in H3K27me3 at the Ccr7 locus in cDCs and moDCs occurs during lineage commitment. Monocyte-DC progenitors (MDPs) can give rise to both monocytes and pre-DCs (32). We therefore compared histone modifications in the latter two types of progenitor cells following their purification from BM. Unexpectedly, monocytes and pre-DCs had similar amounts of H3K27me3 at the Ccr7 promoter (Figure 5A), and these amounts were much lower than that seen for either BM-elicited or lung moDCs (Figures 3B and 4D). Thus, differentiation of MDPs to monocytes in the BM is not immediately accompanied by epigenetic repression of Ccr7.

Figure 5. Monocytes and their immediate progeny have low levels of H3K27me3 at the Ccr7 promoter.

(A) ChIP-QPCR analysis of the Ccr7 promoter or Hoxc10 locus (reference gene) in monocytes (mono) or pre-DCs following immunoprecipitation with either anti-H3K27me3 (black bars) or nonspecific IgG (white bars) antibodies. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.e.m (after normalization to input DNA) of combined data from three independent experiments. (B) Gating strategy for purifying lung-resident CD11bhiCD88hi moDCs and Ly-6ChiCD11bhi inflammatory DCs (infDCs) from LPS-treated lungs. The cytogram depicts CD88 and Ly-6C expression after gating on CD11chi Autofluorescence−I-AbhiCD11bhi lung cells. (C) ChIP-QPCR analysis of the Ccr7 promoter or Hoxc10 locus (reference gene) in Ly-6Chi infDCs or CD88hi moDCs. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.e.m (after normalization to input DNA) of combined data from three independent experiments. *P<0.05.

Epigenetic repression of the Ccr7 promoter is gradually established during monocyte differentiation into DCs

The similar amounts of H3K27me3 at the Ccr7 locus of monocytes and pre-DCs suggested that this epigenetic modification is acquired after monocyte senter peripheral tissues and differentiate into moDCs. We first investigated whether monocyte emigration into pulmonary tissues triggers epigenetic repression of Ccr7. Airway exposure to LPS results in the recruitment of Ly-6Chi monocytes to the lungs, which rapidly differentiate into Ly-6ChiCD11bhi inflammatory DCs (33). Inflammatory DCs also express CD88, but can be distinguished from lung-resident moDCs by their high-level expression of Ly-6C (Figure 5B). ChIP-QPCR analysis of inflammatory DCs revealed that they had significantly lower levels of Ccr7-associated H3K27me3 compared to lung-resident moDCs (Figure 5C). Indeed, inflammatory DCs and BM monocytes had similar low levels of H3K27me3 at the Ccr7 locus (Figures 5A and 5C). Thus, extravasation of monocytes into the lung parenchyma does not immediately result in epigenetic repression of Ccr7.

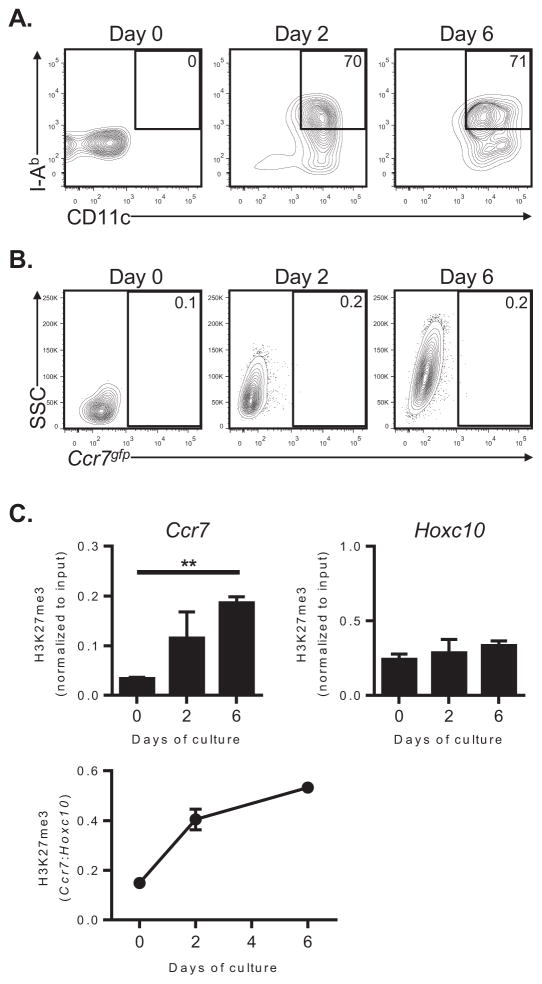

We next investigated whether epigenetic repression of Ccr7 is established during the later stages of monocyte differentiation into moDCs. We have previously shown that only a very small percentage of adoptively transferred monocytes enter the lungs and differentiate into resident moDCs (10). Therefore, it was not possible to accurately track the fate of large numbers of monocytes in the lung for an extended period. As an alternative approach, we purified Ly-6Chi monocytes from BM and followed epigenetic changes at theCcr7 promoter during ex vivo differentiation of these cells into moDCs (34). As expected, during six days of culture in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4, monocytes differentiated into CD11chiI-Abhi moDCs (Figure 6A). As we had seen previously with BM progenitors cultured under these same conditions, monocyte-derived cells failed to express Ccr7, even after their stimulation with LPS (Figure 6B). During ex vivo moDC differentiation, we observed a significant increase inCcr7-associated H3K27me3 (Figure 6C). In contrast, the level of H3K27me3 at the Hoxc10 locus remained stable during the culture period (Figure 6C), indicating the observed changes at the Ccr7 locus were not due to a genome-wide increase in H3K27me3. Consistent with this, we did not detect increased expression of the PRC2 core subunits EZH2, EED, SUZ12 and RbAp48 during moDC differentiation (Supplemental Figure 2). Overall, these findings suggest that epigenetic silencing of Ccr7 occurs in a specific and gradual manner during the differentiation of monocytes into lung-resident moDCs.

Figure 6. Epigenetic repression of the Ccr7 promoter is gradually established during monocyte differentiation to moDCs.

(A–C) Ly-6Chi monocytes sorted from the BM of wild type (A and C) or Ccr7gfp reporter mice (B) were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 for 6 days. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (A–B) or ChIP-QPCR (C) at the indicated time points. (A) Cytograms showing CD11c and I-Ab expression on monocytes at the indicated time points during culture. Data are from a single experiment, representative of two. (B) Cytograms depict Ccr7gfp expression by monocytes at the indicated time points during culture. Cells were treated with 100 ng ml−1 LPS for 24 hours prior to flow cytometric analysis. Data are from a single experiment, representative of two. (C) Quantification of H3K27me3 by ChIP-QPCR analysis of the Ccr7 promoter or Hoxc10 locus (reference gene) during monocyte differentiation into moDCs. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.e.m (after normalization to input DNA) of combined data from two independent experiments. The line graph depicts the mean ratio (± s.e.m) of Ccr7-associated H3K27me3 to Hoxc10-associated H3K27me3. **P<0.01.

DISCUSSION

The migration of DCs to lung-draining LN is critical for shaping nascent immune responses to inhaled antigens (1, 3, 10). Given that the DC network is comprised of populations with distinct functional roles, it is not surprising that only certain subsets possess the ability to express Ccr7 and migrate to regional LN. We have previously demonstrated that the developmental lineage of DCs is important for determining their migratory potential (10). In the current study, we investigated whether epigenetic mechanisms might contribute to lineage-specific Ccr7 expression. We found that in BM-elicited or lung moDCs, the Ccr7 promoter is enriched for the repressive histone mark H3K27me3. Consequently, Ccr7 induction is transcriptionally repressed in moDCs but not cDCs. The repressive histone modifications are not established during lineage-commitment in the BM, but are formed during monocyte differentiation into moDCs in the periphery. Our results suggest that a combination of lineage-specific epigenetic mechanisms and cues within the tissue microenvironment help determine the migratory capacity, and consequently the functional role, of lung DC subsets. The nonmigratory status of moDCs suggests that they do not function during antigen sensitization, which is thought to require DC migration, but rather during the effector phase of immune responses within the lung. Indeed, a recent report found that moDCs were largely responsible for antigen presentation and proinflammatory cytokine secretion in the lungs during allergen challenge (3). Whether lung moDCs are more efficient than cDCs at stimulating effector or memory T cells is an important question for future studies.

While there has been recent progress in identifying the transcriptional profiles of different DC subtypes (9, 12, 35), little is known regarding the epigenetic mechanisms regulating gene expression in DCs. This is in contrast to T helper cell differentiation, where epigenetic changes at lineage-specific genes have been well documented (36). Epigenetic mechanisms are likely responsible for regulating several aspects of DC immunobiology. For example, DCs treated with histone deacetylase inhibitors have altered expression of proinflammatory cytokines and costimulatory molecules, arguing that dynamic changes in histone modifications are important during DC maturation (37). Furthermore, heritable epigenetic changes have been shown to influence DC function during adaptive immune responses. Splenic DCs from offspring of allergen-sensitized mothers had altered genomic DNA methylation patterns, which was associated with a Th2-skewing phenotype when compared to DCs from pups of naïve mothers (38). The current study provides further insight into how epigenetic changes can influence DC function, specifically through regulation of their migration. By epigenetically silencing the Ccr7 gene, moDCs assume a nonmigratory phenotype within the lung.

Unexpectedly, we found that epigenetic repression of Ccr7 is not established early during DC lineage commitment, but rather during monocyte differentiation into moDCs. Using an ex vivo model for generating moDCs from BM monocytes, we observed a gradual but specific increase in H3K27me3 at the Ccr7 promoter. It is possible that ex vivo generation of moDCs from monocytes does not accurately reflect in vivo differentiation of moDCs in the lung. However, ex vivo-generated and lung-resident moDCs had comparable surface marker phenotypes and histone modifications at the Ccr7 locus, suggesting that they undergo similar differentiation pathways. Improvements in cellular fate-mapping and ChIP analyses using small cell numbers will help facilitate future epigenetic studies of lung-resident moDCs and other rare cell types.

Interestingly, we observed low levels of H3K27me3 at the Ccr7 locus in monocytes, implying that Ccr7 retains the potential to be expressed in these cells or their progeny. This might explain contradicting reports that monocyte-derived antigen presenting cells (APCs) in the colon can express Ccr7 and migrate to LN (39). Furthermore, epidermal Langerhans cells – which are derived from monocytes (40) – are reported to express Ccr7 and traffic to skin-draining LN (41). It is conceivable that tissue-specific factors can regulate epigenetic silencing of the Ccr7 locus in monocyte-derived APCs. While the identity of these factors is unknown, several cytokines can modulateCcr7 expression in activated DCs, including thymic stromal lymphopoietin (42), IL-33 (43), and type I interferons (44). Additionally, our studies with BM-elicited moDCs and ex vivo cultured monocytes suggest a role of GM-CSF and Flt3L in determining epigenetic modifications at the Ccr7 locus. The observation that GM-CSF may lead to epigenetic repression of Ccr7 in monocytes has significant implications for DC-based immunotherapies, as this cytokine is frequently used to generate DCs from peripheral blood monocytes in humans. Since LN-homing by DCs is considered necessary for optimal stimulation of antigen-specific T cells (45), understanding how GM-CSF and Flt3L influence the migratory potential of DCs will be essential for designing effective DC vaccines.

While our studies demonstrate that Ccr7-associated H3K27me3 increases during monocyte differentiation into moDCs, the mechanisms by which occurs are currently unclear. Because trimethylation of H3K27 is mediated by the chromatin modification complex PRC2, we studied expression of genes encoding its core subunits (EZH2, EED, SUZ12 and RbAp48) during monocyte differentiation to moDCs (46). We found that expression of these genes generally decreased during moDC development (Supplemental Figure 2), which is consistent with the previously reported decrease in Ezh2 expression during cellular differentiation (47). Therefore, it is likely that the increased Ccr7-associated H3K27me3 results from a selective recruitment of PRC2 to the Ccr7 locus by specific DNA-binding proteins or transcription factors (48). Identification of such factors should further our understanding of how the Ccr7 locus is regulated in moDCs.

Although our observations suggest that H3K27me3 leads to silencing of Ccr7 in moDCs, demonstrating direct causality is difficult. It is possible to inhibit H3K27me3 by targeting the histone methyltransferase EZH2, but this can affect multiple aspects of cell differentiation and survival (49). Not surprisingly, we found that the EZH2 inhibitor 3-deazaneplanocin A interfered with DC development from BM progenitors and monocytes, thus precluding any specific studies on Ccr7 expression (Moran, unpublished observations). Strategies that specifically inhibit EZH2 activity at the Ccr7 locus will be important for addressing this issue. It is also likely that H3K27me3 is but one of many mechanisms involved with regulating Ccr7 expression. Monocytes and monocyte-derived Ly-6Chi inflammatory DCs have low levels of Ccr7-associated H3K27me3, yet they do not expressCcr7 after stimulation with LPS (10 and Figure6A). This implies that in addition to a receptive chromatin configuration at the Ccr7 promoter, lineage-specific transcription factors are also necessary for driving gene expression. Several transcription factors have been reported to regulate Ccr7 expression, including nuclear factor kappa B (50), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (51), Runx3 (52), liver X receptor (53), and IFN regulatory factor 4 (54). The migratory properties of cDCs and moDCs may be dependent upon differential expression of these transcription factors. Additional epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation and noncoding RNAs, might also regulate Ccr7 expression. TheCcr7 promoter does not contain any CpG islands, but it is possible that DNA methylation in upstream enhancers or intronic regions may influence Ccr7 expression. Noncoding RNAs that inhibit CCR7production have been described in human T lymphocytes and breast cancer cells (55, 56), but not in APCs. Future studies will help clarify the relative contribution of lineage-specific transcription factors and other epigenetic marks to Ccr7 regulation.

Overall, our findings suggest that by controlling Ccr7 expression, lineage-specific epigenetic mechanisms can influence the function of specific DC subsets. Identifying the endogenous and cell-intrinsic factors that direct Ccr7-specific epigenetic changes will likely uncover pathways that can be targeted to modulate DC migration. In turn, the ability to manipulate the migratory properties of DCs represents a novel strategy for improving DC-based immunotherapies and for treating immune-mediated diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant #5 T32 AI 007062-34 and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the NIEHS.

We thank Carl Bortner and Maria Sifre with the NIEHS Flow Cytometry Center for help with cell sorting; the NIEHS Protein Expression Core Facility for production of recombinant human Flt3L; Ligon Perrow for mouse colony management; Komal Patel for technical assistance; Thomas Randall for bioinformatics consultation; and Michael Fessler and Harriet Kinyamu for critical review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used in this article

- BM

bone marrow

- cDC

conventional dendritic cell

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DC

dendritic cell

- Flt3L

Flt3 ligand

- H3K27me3

histone 3 lysine 27 trimethylation

- LN

lymph node

- moDC

monocyte-derived dendritic cell

- PRC2

polycomb repressive complex 2

- pre-DC

precursor of DC

- QPCR

quantitative PCR

References

- 1.Vermaelen KY, Carro-Muino I, Lambrecht BN, Pauwels RA. Specific migratory dendritic cells rapidly transport antigen from the airways to the thoracic lymph nodes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2001;193:51–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hintzen G, Ohl L, del Rio ML, Rodriguez-Barbosa JI, Pabst O, Kocks JR, Krege J, Hardtke S, Forster R. Induction of tolerance to innocuous inhaled antigen relies on a CCR7-dependent dendritic cell-mediated antigen transport to the bronchial lymph node. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:7346–7354. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plantinga M, Guilliams M, Vanheerswynghels M, Deswarte K, Branco-Madeira F, Toussaint W, Vanhoutte L, Neyt K, Killeen N, Malissen B, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Conventional and monocyte-derived CD11b (+) dendritic cells initiate and maintain T helper 2 cell-mediated immunity to house dust mite allergen. Immunity. 2013;38:322–335. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geurtsvan Kessel CH, Willart MA, van Rijt LS, Muskens F, Kool M, Baas C, Thielemans K, Bennett C, Clausen BE, Hoogsteden HC, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF, Lambrecht BN. Clearance of influenza virus from the lung depends on migratory langerin+CD11b- but not plasmacytoid dendritic cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:1621–1634. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forster R, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Rot A. CCR7 and its ligands: balancing immunity and tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:362–371. doi: 10.1038/nri2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broggi A, Zanoni I, Granucci F. Migratory conventional dendritic cells in the induction of peripheral T cell tolerance. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2013;94:903–911. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0413222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. Lung dendritic cells in respiratory viral infection and asthma: from protection to immunopathology. Annual review of immunology. 2012;30:243–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakano H, Free ME, Whitehead GS, Maruoka S, Wilson RH, Nakano K, Cook DN. Pulmonary CD103 (+) dendritic cells prime Th2 responses to inhaled allergens. Mucosal immunology. 2012;5:53–65. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satpathy AT, Wu X, Albring JC, Murphy KM. Re(de)fining the dendritic cell lineage. Nature immunology. 2012;13:1145–1154. doi: 10.1038/ni.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakano H, Burgents JE, Nakano K, Whitehead GS, Cheong C, Bortner CD, Cook DN. Migratory properties of pulmonary dendritic cells are determined by their developmental lineage. Mucosal immunology. 2013;6:678–691. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu K, Nussenzweig MC. Origin and development of dendritic cells. Immunological reviews. 2010;234:45–54. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, Mortha A. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annual review of immunology. 2013;31:563–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogunovic M, Ginhoux F, Helft J, Shang L, Hashimoto D, Greter M, Liu K, Jakubzick C, Ingersoll MA, Leboeuf M, Stanley ER, Nussenzweig M, Lira SA, Randolph GJ, Merad M. Origin of the lamina propria dendritic cell network. Immunity. 2009;31:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamoutounour S, Guilliams M, Montanana Sanchis F, Liu H, Terhorst D, Malosse C, Pollet E, Ardouin L, Luche H, Sanchez C, Dalod M, Malissen B, Henri S. Origins and functional specialization of macrophages and of conventional and monocyte-derived dendritic cells in mouse skin. Immunity. 2013;39:925–938. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy KM. Transcriptional control of dendritic cell development. Advances in immunology. 2013;120:239–267. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417028-5.00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HP, Lee YS, Park JH, Kim YJ. Transcriptional and epigenetic networks in the development and maturation of dendritic cells. Epigenomics. 2013;5:195–204. doi: 10.2217/epi.13.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondilis-Mangum HD, Wade PA. Epigenetics and the adaptive immune response. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2013;34:813–825. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee DU, Agarwal S, Rao A. Th2 lineage commitment and efficient IL-4 production involves extended demethylation of the IL-4 gene. Immunity. 2002;16:649–660. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avni O, Lee D, Macian F, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH, Rao A. T(H) cell differentiation is accompanied by dynamic changes in histone acetylation of cytokine genes. Nature immunology. 2002;3:643–651. doi: 10.1038/ni808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei G, Wei L, Zhu J, Zang C, Hu-Li J, Yao Z, Cui K, Kanno Y, Roh TY, Watford WT, Schones DE, Peng W, Sun HW, Paul WE, O’Shea JJ, Zhao K. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verstraete K, Koch S, Ertugrul S, Vandenberghe I, Aerts M, Vandriessche G, Thiede C, Savvides SN. Efficient production of bioactive recombinant human Flt3 ligand in E. coli. The protein journal. 2009;28:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s10930-009-9164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakano H, Cook DN. Pulmonary antigen presenting cells: isolation, purification, and culture. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 2013;1032:19–29. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-496-8_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carabana J, Watanabe A, Hao B, Krangel MS. A barrier-type insulator forms a boundary between active and inactive chromatin at the murine TCRbeta locus. Journal of immunology. 2011;186:3556–3562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Y, Zhan Y, Lew AM, Naik SH, Kershaw MH. Differential development of murine dendritic cells by GM-CSF versus Flt3 ligand has implications for inflammation and trafficking. Journal of immunology. 2007;179:7577–7584. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satpathy AT, Kc W, Albring JC, Edelson BT, Kretzer NM, Bhattacharya D, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. Zbtb46 expression distinguishes classical dendritic cells and their committed progenitors from other immune lineages. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209:1135–1152. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meredith MM, Liu K, Darrasse-Jeze G, Kamphorst AO, Schreiber HA, Guermonprez P, Idoyaga J, Cheong C, Yao KH, Niec RE, Nussenzweig MC. Expression of the zinc finger transcription factor zDC (Zbtb46, Btbd4) defines the classical dendritic cell lineage. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209:1153–1165. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patenaude J, D’Elia M, Cote-Maurais G, Bernier J. LPS response and endotoxin tolerance in Flt-3L-induced bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Cellular immunology. 2011;271:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tserel L, Kolde R, Rebane A, Kisand K, Org T, Peterson H, Vilo J, Peterson P. Genome-wide promoter analysis of histone modifications in human monocyte-derived antigen presenting cells. BMC genomics. 2010;11:642. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh T-Y, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K. High-Resolution Profiling of Histone Methylations in the Human Genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernstein BE, Birney E, Dunham I, Green ED, Gunter C, Snyder M. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlitzer A, McGovern N, Teo P, Zelante T, Atarashi K, Low D, Ho AW, See P, Shin A, Wasan PS, Hoeffel G, Malleret B, Heiseke A, Chew S, Jardine L, Purvis HA, Hilkens CM, Tam J, Poidinger M, Stanley ER, Krug AB, Renia L, Sivasankar B, Ng LG, Collin M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Honda K, Haniffa M, Ginhoux F. IRF4 transcription factor-dependent CD11b+ dendritic cells in human and mouse control mucosal IL-17 cytokine responses. Immunity. 2013;38:970–983. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fogg DK, Sibon C, Miled C, Jung S, Aucouturier P, Littman DR, Cumano A, Geissmann F. A clonogenic bone marrow progenitor specific for macrophages and dendritic cells. Science. 2006;311:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1117729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheong C, Matos I, Choi JH, Dandamudi DB, Shrestha E, Longhi MP, Jeffrey KL, Anthony RM, Kluger C, Nchinda G, Koh H, Rodriguez A, Idoyaga J, Pack M, Velinzon K, Park CG, Steinman RM. Microbial stimulation fully differentiates monocytes to DC-SIGN/CD209 (+) dendritic cells for immune T cell areas. Cell. 2010;143:416–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller JC, Brown BD, Shay T, Gautier EL, Jojic V, Cohain A, Pandey G, Leboeuf M, Elpek KG, Helft J, Hashimoto D, Chow A, Price J, Greter M, Bogunovic M, Bellemare-Pelletier A, Frenette PS, Randolph GJ, Turley SJ, Merad M. Deciphering the transcriptional network of the dendritic cell lineage. Nature immunology. 2012;13:888–899. doi: 10.1038/ni.2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanno Y, Vahedi G, Hirahara K, Singleton K, O’Shea JJ. Transcriptional and epigenetic control of T helper cell specification: molecular mechanisms underlying commitment and plasticity. Annual review of immunology. 2012;30:707–731. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bode KA, Schroder K, Hume DA, Ravasi T, Heeg K, Sweet MJ, Dalpke AH. Histone deacetylase inhibitors decrease Toll-like receptor-mediated activation of proinflammatory gene expression by impairing transcription factor recruitment. Immunology. 2007;122:596–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mikhaylova L, Zhang Y, Kobzik L, Fedulov AV. Link between epigenomic alterations and genome-wide aberrant transcriptional response to allergen in dendritic cells conveying maternal asthma risk. PloS one. 2013;8:e70387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zigmond E, Varol C, Farache J, Elmaliah E, Satpathy AT, Friedlander G, Mack M, Shpigel N, Boneca IG, Murphy KM, Shakhar G, Halpern Z, Jung S. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2012;37:1076–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merad M, Manz MG, Karsunky H, Wagers A, Peters W, Charo I, Weissman IL, Cyster JG, Engleman EG. Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nature immunology. 2002;3:1135–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohl L, Mohaupt M, Czeloth N, Hintzen G, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J, Blankenstein T, Henning G, Forster R. CCR7 governs skin dendritic cell migration under inflammatory and steady-state conditions. Immunity. 2004;21:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kitajima M, Ziegler SF. Cutting edge: identification of the thymic stromal lymphopoietin-responsive dendritic cell subset critical for initiation of type 2 contact hypersensitivity. Journal of immunology. 2013;191:4903–4907. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Besnard AG, Togbe D, Guillou N, Erard F, Quesniaux V, Ryffel B. IL-33-activated dendritic cells are critical for allergic airway inflammation. European journal of immunology. 2011;41:1675–1686. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parlato S, Santini SM, Lapenta C, Di Pucchio T, Logozzi M, Spada M, Giammarioli AM, Malorni W, Fais S, Belardelli F. Expression of CCR-7, MIP-3beta, and Th-1 chemokines in type I IFN-induced monocyte-derived dendritic cells: importance for the rapid acquisition of potent migratory and functional activities. Blood. 2001;98:3022–3029. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MartIn-Fontecha A, Sebastiani S, Hopken UE, Uguccioni M, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Regulation of dendritic cell migration to the draining lymph node: impact on T lymphocyte traffic and priming. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;198:615–621. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Meara MM, Simon JA. Inner workings and regulatory inputs that control Polycomb repressive complex 2. Chromosoma. 2012;121:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s00412-012-0361-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ezhkova E, Pasolli HA, Parker JS, Stokes N, Su IH, Hannon G, Tarakhovsky A, Fuchs E. Ezh2 orchestrates gene expression for the stepwise differentiation of tissue-specific stem cells. Cell. 2009;136:1122–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim J, Kim H. Recruitment and biological consequences of histone modification of H3K27me3 and H3K9me3. ILAR journal / National Research Council, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources. 2012;53:232–239. doi: 10.1093/ilar.53.3-4.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tan J, Yang X, Zhuang L, Jiang X, Chen W, Lee PL, Karuturi RK, Tan PB, Liu ET, Yu Q. Pharmacologic disruption of Polycomb-repressive complex 2-mediated gene repression selectively induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Genes & development. 2007;21:1050–1063. doi: 10.1101/gad.1524107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hopken UE, Foss HD, Meyer D, Hinz M, Leder K, Stein H, Lipp M. Up-regulation of the chemokine receptor CCR7 in classical but not in lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin disease correlates with distinct dissemination of neoplastic cells in lymphoid organs. Blood. 2002;99:1109–1116. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Angeli V, Hammad H, Staels B, Capron M, Lambrecht BN, Trottein F. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibits the migration of dendritic cells: consequences for the immune response. Journal of immunology. 2003;170:5295–5301. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fainaru O, Shseyov D, Hantisteanu S, Groner Y. Accelerated chemokine receptor 7-mediated dendritic cell migration in Runx3 knockout mice and the spontaneous development of asthma-like disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:10598–10603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504787102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Villablanca EJ, Raccosta L, Zhou D, Fontana R, Maggioni D, Negro A, Sanvito F, Ponzoni M, Valentinis B, Bregni M, Prinetti A, Steffensen KR, Sonnino S, Gustafsson JA, Doglioni C, Bordignon C, Traversari C, Russo V. Tumor-mediated liver X receptor-alpha activation inhibits CC chemokine receptor-7 expression on dendritic cells and dampens antitumor responses. Nature medicine. 2010;16:98–105. doi: 10.1038/nm.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bajana S, Roach K, Turner S, Paul J, Kovats S. IRF4 promotes cutaneous dendritic cell migration to lymph nodes during homeostasis and inflammation. Journal of immunology. 2012;189:3368–3377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim SJ, Shin JY, Lee KD, Bae YK, Sung KW, Nam SJ, Chun KH. MicroRNA let-7a suppresses breast cancer cell migration and invasion through downregulation of C-C chemokine receptor type 7. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2012;14:R14. doi: 10.1186/bcr3098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smigielska-Czepiel K, van den Berg A, Jellema P, Slezak-Prochazka I, Maat H, van den Bos H, van der Lei RJ, Kluiver J, Brouwer E, Boots AM, Kroesen BJ. Dual role of miR-21 in CD4+ T-cells: activation-induced miR-21 supports survival of memory T-cells and regulates CCR7 expression in naive T-cells. PloS one. 2013;8:e76217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.