Abstract

Introduction

Malignant pleural effusion can complicate most cancers. It causes breathlessness and requires hospitalisation for invasive pleural drainages. Malignant effusions often herald advanced cancers and limited prognosis. Minimising time spent in hospital is of high priority to patients and their families. Various treatment strategies exist for the management of malignant effusions, though there is no consensus governing the best choice. Talc pleurodesis is the conventional management but requires hospitalisation (and substantial healthcare resources), can cause significant side effects, and has a suboptimal success rate. Indwelling pleural catheters (IPCs) allow ambulatory fluid drainage without hospitalisation, and are increasingly employed for management of malignant effusions. Previous studies have only investigated the length of hospital care immediately related to IPC insertion. Whether IPC management reduces time spent in hospital in the patients’ remaining lifespan is unknown. A strategy of malignant effusion management that reduces hospital admission days will allow patients to spend more time outside hospital, reduce costs and save healthcare resources.

Methods and analysis

The Australasian Malignant Pleural Effusion (AMPLE) trial is a multicentred, randomised trial designed to compare IPC with talc pleurodesis for the management of malignant pleural effusion. This study will randomise 146 adults with malignant pleural effusions (1:1) to IPC management or talc slurry pleurodesis. The primary end point is the total number of days spent in hospital (for any admissions) from treatment procedure to death or end of study follow-up. Secondary end points include hospital days specific to pleural effusion management, adverse events, self-reported symptom and quality-of-life scores.

Ethics and dissemination

The Sir Charles Gairdner Group Human Research Ethics Committee has approved the study as have the ethics boards of all the participating hospitals. The trial results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at scientific conferences.

Trial registration numbers

Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry—ACTRN12611000567921; National Institutes of Health—NCT02045121.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Multicentre, randomised trial of indwelling pleural catheter versus talc pleurodesis in malignant pleural effusion.

The study compares the effects of intervention on total days patients spent in hospital, from any causes, until death or end of study follow-up—a meaningful and important end point for patients with advanced cancers, which has not been studied before.

The study includes centres from Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and Hong Kong.

Evaluation of the relative merits of IPC versus talc slurry pleurodesis in pragmatic, ‘real life’, clinical environments.

Patients with a malignant pleural effusion are a diverse group with a wide range of underlying cancers, demographics, comorbidity and prognosis.

Malignant pleural effusion is common and can complicate most cancers, including one-third of patients with lung and breast carcinomas1 2 and most (>90%) patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma.3 Malignant pleural effusions cause breathlessness and frequently require hospitalisation for invasive pleural drainage procedures. In Western Australia (population 1.8 million) alone, inpatient care cost for malignant pleural effusions is estimated to exceed US$12 million per year.

Malignant effusions often herald advanced cancers and limited prognosis. The average life expectancy for patients with this condition is 3 (for metastatic carcinomas) to 9 months (for mesothelioma). Minimising days spent in hospital to maximise time spent at home and/or with family is a high priority to patients.4 5 The ideal treatment approach should include effective long-term symptoms relief (especially dyspnoea), minimal hospitalisation and have the least adverse effects.6 Conventional management involves inpatient talc pleurodesis, which requires hospitalisation, often of 4–6 days in reported series.7 8

Talc pleurodesis also has a high failure rate, which necessitates further pleural interventions/drainages and hospital care. A randomised trial of 482 patients with malignant pleural effusions showed that talc pleurodesis, irrespective of whether delivered by thoracoscopic poudrage or talc slurry via tube thoracostomy, successfully controlled fluid recurrence in only ∼75% of patients at 1 month, and 50% by 6 months.9 Our recent study of pleurodesis in patients with mesothelioma also showed that 71% had fluid recurrence, and 32% required further pleural interventions.10

Talc pleurodesis is known also to have significant side effects.11 Pain and fever are common, and transient hypoxaemia in the several days following pleurodesis days has been reported. It is now recognised that pleurodesis with non-graded talc (still the only type of talc preparation available in many countries) can result in acute respiratory distress syndrome.12 In the study of Dresler et al,9 5.3% of 419 evaluable patients developed respiratory failure with a mortality rate of 2%.

Indwelling pleural catheters (IPCs) allow ambulatory fluid drainage and are free from side effects, the need for hospitalisation and costs of pleurodesis.13 IPC is increasingly employed for the management of malignant effusions.14 15 To date, two randomised studies have compared IPC with talc pleurodesis,7 16 and another with doxycycline pleurodesis.8 Davies et al7 randomised 106 patients with malignant effusions and showed that IPC offered equally good symptom relief (dyspnoea and quality-of-life scores were the key end points) compared with talc pleurodesis. Putnam et al8 randomised 144 patients and also found similar symptomatic benefits between IPC and doxycycline pleurodesis. Patients undergoing pleurodesis spend longer times in hospital for the initial procedure (median 4 vs 0 days as reported by Davies et al7 and 6.5 vs 1.0 days by Putnam et al8).

Whether the use of IPC or pleurodesis impacts on the subsequent need for hospitalisation in the patient's remaining lifespan has not been defined. Four comparisons of pleurodesis and IPC all found that patients undergoing pleurodesis were more likely to need subsequent pleural drainage procedures with a pooled failure rate of 22.1% (36/163), compared with 8.9% in IPC patients (21/236).7 8 17 18 On the other hand, IPC requires ongoing care and is known to have a different set of complications19 (eg, infection,20 blockage, symptomatic loculations, catheter track metastases,21 etc) which could trigger hospital care.

In a pilot, non-randomised patient-choice study, we found in 65 patients with malignant effusions that those who elected to have IPC management spent fewer days in hospital in their remaining lifespan in pleural-related as well as all-cause hospital stay compared with those treated with talc pleurodesis.17 The pleurodesis group spent 11.2% of their remaining life in hospital as opposed to 8.0% for the group with IPC (p<0.001). The AMPLE (Australasian Malignant Pleural Effusion) trial is designed to further evaluate the findings in a multicentred and randomised setting.

Methods and analysis

The AMPLE trial is a multicentred, prospective, randomised trial designed to compare IPC with talc pleurodesis for the management of malignant pleural effusion. The trial is registered on the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ACTRN12611000567921). The study is also registered on the West Australian Health Research Management System (ID: 2019). The trial will be conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and the National Statement.

The primary end point is the total number of days spent in hospital (for any cause of admission) from treatment procedure to death or end of study follow-up. The secondary research end points include:

Admissions (days and number of episodes) for pleural effusion-associated causes. This includes admissions for management of pleural effusion, associated symptoms, related procedures and/or their complications.

Survival and adverse events from enrolment to death or end of follow-up.

Breathlessness score and self-reported quality-of-life scores recorded at regular intervals from enrolment to death or end of follow-up.

Health cost assessment.

Need for further pleural interventions.

Setting

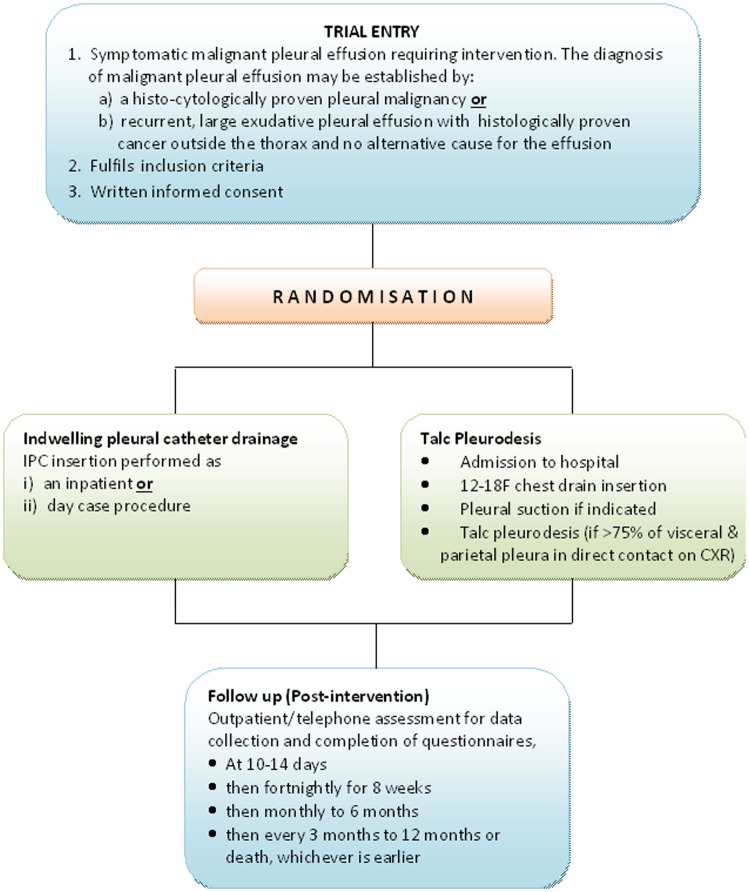

The study will recruit 146 patients with a malignant pleural effusion (see below for the inclusion criteria) requiring effusion management from the participating centres (see online supplementary appendix 1). Patients will be randomised to receive either IPC or pleurodesis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart (IPC, indwelling pleural catheter; CXR, chest X-ray).

Power calculation

In our pilot non-randomised study,17 those who chose to have IPC (n=34) for management of their malignant effusion spent a median of 6.5 days (IQR 3.75–13.0) in hospital compared with 18.0 days (IQR 8.0–26.0; p=0.002) in the talc group (n=31). The primary response data are likely to be highly skewed, and hence a non-parametric test would be more appropriate. To examine the potential benefit of reduction in hospital stay using IPC, we estimate 65 patients in each group are needed. The study will be able (with 80% power and α=0.05) to detect a difference of 5 or more days spent in hospital, based on preliminary estimates of 18 days in the pleurodesis group (from the pilot study17) and a SD of 9.3. Allowing for a lost-to-follow-up rate of 12%, 73 patients per group will be needed, to make a total recruitment target of 146. This is a conservative estimate as no patient was lost to follow-up in the pilot study.

Statistical plan—missing data

In common with many clinical studies, missing data may exist either in the form of total non-response (eg, attrition due to death or patient withdrawal) or item non-response (when some but not all the required information is collected from the patients). We will attempt to minimise the missing data due to item non-response. Throughout the duration of the trial, participants will have regular contact with the respiratory department, as well as with the research team. The patient will be asked to complete the forms while at clinic. This will maximise proper and complete data collection. The research team will document as accurately as possible the reasons for any non-completion or missing data, thereby minimising truly absent data. The expected dropout from patient death has been factored into the power calculation and is based on survival figures. The detail of the statistical analysis will be set out in the Statistical Analysis Plan.

Participant screening and selection

Potential participants will be recruited from the respiratory and/or oncology clinics of the participating centres. Patients with a known or likely malignant pleural effusion that requires management to control symptoms will be identified by the clinicians. The potential patient will be approached about the possibility of taking part in the study if they are at the point of requiring intervention for the management of their malignant pleural effusion. They will be given an explanation of the study by the doctor and then given the participant information and consent form (PICF) to read through and ask questions of the doctor. An informed consent will be obtained before study enrolment. As both treatment options are well established and approved therapies, one or the other would be employed irrespective of whether the patient decided to be enrolled in the study.

Individual centres will maintain a screening log of patients including those who did not enter the study.

Inclusion criteria

- Patients must have a symptomatic malignant pleural effusion requiring intervention. The diagnosis may be established by:

- Histocytologically proven pleural malignancy or

- Recurrent large exudative pleural effusion with histologically proven cancer outside the thorax and no alternative cause

Written informed consent

Exclusion criteria

Age under 18 years

Effusion smaller than 2 cm at maximum depth

Expected survival less than 3 months

Chylothorax

Previous lobectomy or pneumonectomy on the side of the effusion

Previous attempted pleurodesis

Pleural infection

Total blood white cell count less than 1.0×109/L

Hypercapnic ventilatory failure

Patients who are pregnant or lactating

Irreversible bleeding diathesis

Irreversible visual impairment

Inability to give informed consent or comply with the protocol

Informed consent

A doctor will confirm patient eligibility prior to consent being taken. Patients will be given the opportunity to consider the PICF and time to ask questions prior to written, informed consent being taken by the study doctor.

Randomisation

Patients will be randomly assigned (1:1) to either an indwelling ambulatory pleural catheter or talc pleurodesis for their malignant pleural effusion.

Randomisation will include minimisation for

Australasian centres versus centres outside Australasia (Singapore and Hong Kong). This is because of potential differences in patient ethnicity and distribution of cancer types;

Mesothelioma versus non-mesothelioma. This is because median survival is significantly longer in mesothelioma compared with metastatic pleural cancers.22 Also, the risk of catheter-associated subcutaneous tumour invasion may be higher with mesothelioma;

The presence versus absence of known trapped lung. The presence of a trapped lung is likely to reduce the likelihood of a successful pleurodesis.

To maintain allocation concealment, randomisation is performed in real time by a web interface (Filemaker Server Advanced, Filemaker Inc, Santa Clara, California, USA). Initially, a minimisation programme was used so that patients within Australia and New Zealand (Australasia) were allocated with a probability of 0.5–0.7 favouring the treatment that would minimise differences between groups on two key prognostic factors (mesothelioma and trapped lung). When Singapore was added as a site in early 2014, stratification by region (Australasia vs Singapore/Hong Kong) was added to account for any potential differences in baseline characteristics between patient and disease cohorts. The probability favouring the treatment that would minimise bias was increased to 0.8 accordingly to compensate for this added variable.23

Standard care

All patients will receive usual standard care, for example, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, as recommended by their attending clinicians. Patients requiring assistance from other services, for example, the surgeons, palliative care team or hospice will be referred when needed by the clinical team. Co-enrolment in other clinical trials will be discussed on an individual basis, but will be considered provided compliance with both protocols is possible.

Interventions

Talc slurry pleurodesis

Bedside talc pleurodesis is a commonly used treatment worldwide.3 Talc is delivered as a suspension in saline via a chest tube, which is clamped for a short time (usually 1–4 h). There are variations among most centres worldwide in the precise details as there is no evidence-based guideline to define the best administration protocols.24 As a pragmatic real-life study, the AMPLE trial allows each centre to perform the talc pleurodesis as per their usual practice, including the choice of the size of chest drain used, timing of talc instillation and chest drain removal.

Indwelling pleural catheter

IPC has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (USA) since the initial safety trials in the late 1990s.25 The catheter remains in situ as long as it is needed, but can be removed if fluid production stops, or if otherwise clinically indicated. All patients are given an information sheet with detailed instructions and contact details for support. Patients with IPCs have the support and care of the experienced community respiratory nurse and the attending clinical team, as per standard care. The attending clinician will decide on the details of aftercare most suitable for individual patients, including drainage frequencies, personnel performing the drainage, etc, as well as management of any complications.

Data collection and management

Clinical data will be collected at the randomisation visit. Patients will be asked to complete two quality-of-life questionnaires (modified EQ-5D and visual analogue scale (VAS) scores) at the baseline. Following the study intervention, patients will be asked to complete a daily VAS score for their breathlessness and one for quality-of-life every day for the following 14 days. A modified EQ-5D will also be completed by the patient on day 8 after the intervention. Follow-up visits will be undertaken at 10–14 days, and then every 2 weeks for 8 weeks, monthly for 6 months and every 3–12 months thereafter, provided it is feasible. Data will be collected on hospital admissions, details of any chemotherapy received and any adverse events. A clinical review will be conducted by the clinician in-charge. When patients are not, or cannot be, seen in clinic, they will receive a phone call from a study doctor or research nurse to enquire about symptoms at the intervention site. They will also complete the above questionnaires.

Primary outcome

The number of days spent in hospital (bed days) for any cause for all hospital admissions following intervention, until death or the end of the study follow-up. The primary end point is chosen as it is the most meaningful outcome for patients with cancer and their clinicians. Hospital admissions will be further categorised and the days of admissions directly attributable to the pleural effusion and/or its treatment will be recorded as ‘effusion-related’ (a secondary end point).

Given the impossibility of blinding, hospital admissions will be decided by the independent treating physicians, not by the investigators, wherever possible. The reason(s) for admission must be documented and satisfy at least one of the following criteria:

A procedure is required that cannot be performed in the outpatient setting because of the need for >2 h of close nursing or medical attention.

A coexisting or new medical problem requires inpatient therapy.

Cancer or effusion-related symptoms cannot be adequately controlled at home with community nursing, general practitioner and outpatient clinic support.

The number of days spent in hospital is defined as the number of nights the patient is an inpatient at midnight. Any hospital admission involving one or more days will be counted towards the primary outcome. Therefore day-case procedures including chemotherapy administration will not be included.

An independent assessor, not related to the clinical trial, will assess the validity of the hospital admissions for its justification and duration. Time-to-event analysis will be used to assess length of hospital stay (measured as time from the study intervention until discharge) using a competing risk model, where death is the competing risk.

Secondary outcomes

Admissions (days and number of episodes) for pleural effusion-associated causes. This includes admissions for management of pleural effusion, associated symptoms, related procedures and/or their complications.

Survival and adverse events from enrolment to death or end of follow-up.

Breathlessness (visual analogue) and self-reported quality-of-life scores at regular intervals from enrolment to death or end of follow-up.

Health cost assessment: direct clinical costs from local department coding data and other estimated community-based costs will be captured from patient data.

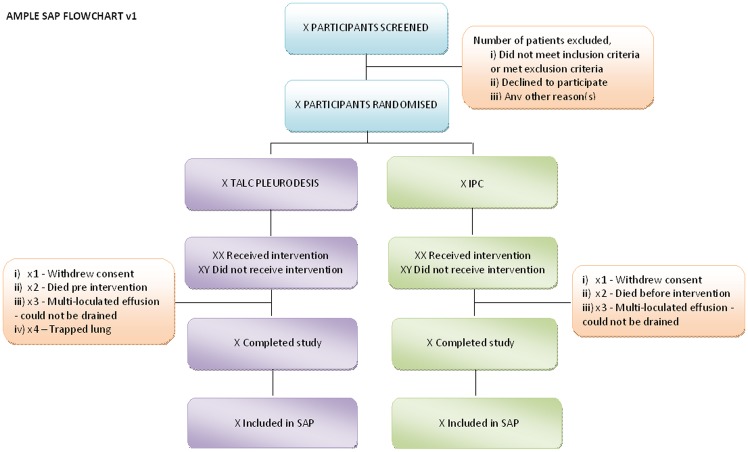

Statistical analysis plan

All outcomes will be analysed for superiority. Superiority analyses will be two-sided and considered statistically significant at the 5% level (figure 2). Unless otherwise stated, all analyses will be adjusted for the minimisation variables described above. Mean imputation will be used during analyses to adjust for missing values of baseline variables.

Figure 2.

Statistical analysis plan (IPC, indwelling pleural catheter).

All analyses will be conducted on an intention-to-treat and also per-protocol basis. The primary end point, that is, total bed days for all hospital admissions will be analysed initially using a Mann-Whitney non-parametric test to compare the two treatment arms. Subsequent supporting analyses will be carried out using a negative binomial model with adjustments made for actual length of follow-up (accounting for death and withdrawals) and important covariates. The total effusion-related bed days for hospital admissions will be analysed similarly to the primary outcome variable. Cox proportional hazards models will be used to analyse time to death, serious adverse events and further pleural intervention. Summaries and frequencies of serious adverse events will be compared between the intervention groups using Fisher’s exact tests. VAS scores will be analysed using linear mixed effects models, including fixed effects of time and time dependent covariates as appropriate and random effects of individual.

Changes to the protocol after the start of the trial

The trial details documented here are consistent with AMPLE trial protocol V.4 (date: 05/05/2014). A summary of the trial amendments can be found in online supplementary appendix 2.

Ethics and dissemination

The trial has been favourably reviewed by the following committees:

Sir Charles Gairdner Group Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) for WA Health hospitals (SCGG 2012-005);

St John of God Health Care Ethics Committee for Bunbury Hospital, WA (Ref: 670);

St Vincent's Health and Aged Care HREC for Holy Spirit, Northside Hospital, Queensland (HREC #13/01);

South Eastern Sydney Local Health District HREC for eastern state hospitals (HREC/13/POWH/110);

Health and Disability Ethics Committee for New Zealand hospitals (CEN/11/06/031/AM04);

National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board Approval for National University Hospital, Singapore (2013/00826);

Institutional Review Board of the University Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster for Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong (UW14-191).

Should a protocol amendment become necessary, the patient consent form and patient information form may need to be revised to reflect the changes to the protocol. It is the responsibility of the investigator to ensure that an amended consent form is reviewed and has received approval/favourable opinion from the ethics committee and other regulatory authorities, as required by ICH GCP and by local laws and regulations, and that it is signed by all patients subsequently entered in the study and those currently in the study, if affected by the amendment (see online supplementary appendix 2).

Monitoring

Data monitoring will be completed by study staff from the lead site. No interim analysis is planned.

Safety reporting

Data will be collected at each trial visit regarding any adverse events and serious adverse events (as defined by ICH GCP). All serious adverse events causally related to treatment procedures will be reported to the relevant HREC, the lead site and the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC).

Data safety

Prior to patient participation in the study, written informed consent must be obtained from each patient (or the patient's legally accepted representative) according to ICH GCP and to the regulatory and legal requirements of the participating country. Each signature must be personally dated by each signatory and the informed consent and any additional patient information form retained by the investigator as part of the study records. A signed copy of the informed consent and any additional patient information must be given to each patient or the patient's legally accepted representative.

The patient must be informed that his/her personal study-related data will be used by the principal investigator in accordance with the local data protection law. The level of disclosure must also be explained to the patient.

The patient must be informed that his/her medical records may be examined by authorised monitors or clinical auditors appointed by appropriate ethics committee members, and by inspectors from regulatory authorities.

Trial monitoring and oversight

The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) will be responsible for overseeing the progress of the trial and will meet at regular intervals. The TSC includes an independent chairperson, independent member, the chief investigator and the trial coordinators. It will review recommendations from the DSMC through their monitoring of adverse events and therefore determine whether or not there is a need for early trial cessation. The committee has a Standard Operating Procedure that defines the terms and conditions of the group. This is to be sent out to all named committee members.

The DSMC will ensure the safety of study participants through the monitoring of the trial procedure, adverse events, serious adverse events and impact on the trial from any relevant new literature. The committee has a Standard Operating Procedure which defines the terms and conditions of the group. This is to be sent out to all named committee members.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: YCGL and ETHF conceived the initial trial concept and conducted the pilot study. CAR is the trial manager and oversees the data collection and running of the trial. RT is the trial coordinator. ETHF, RT, CAR, NAS, EY, FCH, PL, BCHL, FP, RS, LAG, DCLL, AR, MB and YCGL developed the trial design and protocol. RT, YCGL and KM wrote the statistical analysis plan. YCGL is the chief investigator and takes overall responsibility for all aspects of trial design, the protocol and trial conduct. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This project has received funding support from the Cancer Council of Western Australia and the Dust Disease Board of New South Wales. YCGL has also received other research grant support from the Sir Charles Gairdner Research Advisory Council, National Health and Medical Research Council (NH&MRC), Lung Institute of Western Australia (LIWA) and Westcare. ETHF and RT received research scholarship support from NH&MRC; and RT from Western Australia Cancer and Palliative Care Network (WACPCN) and LIWA, Australia. NS has received funding support from the Health Research Council of New Zealand. PL has received funding through a Health Services Research grant from the Ministry of Health, Singapore.

Competing interests: YCGL was a co-investigator of the TIME-2 trial for which Rocket Ltd provided the indwelling catheters and supplies without charge. YCGL is an advisory board member for CareFusion and Sequana Medical Ltd. PL has received an honorarium/travel subsidy to attend Carefusion board meetings.

Ethics approval: Sir Charles Gairdner Group Human Research Ethics Committee (lead site).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Light RW, Lee YC, eds. Textbook of pleural diseases. London, UK: Hodder Arnold, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mishra E, Davies HE, Lee YC. Malignant pleural disease in primary lung cancer. In: Spiro SG, Huber RM, Janes SM, eds. European respiratory society monograph. European Respiratory Society Journals Ltd, 2009:318–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.West SD, Lee YC. Management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Clin Chest Med 2006;27:335–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heffner JE, Nietert PJ, Barbieri C. Pleural fluid pH as a predictor of pleurodesis failure: analysis of primary data. Chest 2000;117:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Thoracic Society. Management of malignant pleural effusions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:1987–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas R, Francis R, Davies HE et al. Interventional therapies for malignant pleural effusions: the present and the future. Respirology 2014;19:809–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the time2 randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012;307:2383–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putnam JB Jr, Light RW, Rodriguez RM et al. A randomized comparison of indwelling pleural catheter and doxycycline pleurodesis in the management of malignant pleural effusions. Cancer 1999;86:1992–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dresler CM, Olak J, Herndon JE II et al. Phase iii intergroup study of talc poudrage vs talc slurry sclerosis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2005;127:909–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fysh ET, Tan SK, Read CA et al. Pleurodesis outcome in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Thorax 2013;68:594–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies HE, Lee YC. Management of malignant pleural effusions: questions that need answers. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2013;19:374–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maskell NA, Lee YC, Gleeson FV et al. Randomized trials describing lung inflammation after pleurodesis with talc of varying particle size. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azzopardi M, Porcel JM, Koegelenberg CFN et al. Controversies in diagnosis and management of malignant pleural effusion. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015; In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee YC, Fysh ET. Indwelling pleural catheter: changing the paradigm of malignant effusion management. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:655–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tremblay A, Michaud G. Single-center experience with 250 tunnelled pleural catheter insertions for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2006;129:362–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demmy TL, Gu L, Burkhalter JE et al. Optimal management of malignant pleural effusions (results of calgb 30102). J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012;10:975–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fysh ET, Waterer GW, Kendall PA et al. Indwelling pleural catheters reduce inpatient days over pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2012;142:394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt BM, Farivar AS, Vallieres E et al. Thoracoscopic talc versus tunneled pleural catheters for palliation of malignant pleural effusions. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:1053–7; discussion 1057–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tremblay A, Mason C, Michaud G. Use of tunnelled catheters for malignant pleural effusions in patients fit for pleurodesis. Eur Respir J 2007;30:759–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fysh ET, Tremblay A, Feller-Kopman D et al. Clinical outcomes of indwelling pleural catheter-related pleural infections: an international multicenter study. Chest 2013;144:1597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas R, Budgeon CA, Kuok YJ et al. Catheter tract metastasis associated with indwelling pleural catheters. Chest 2014;146:557–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clive AO, Kahan BC, Hooper CE et al. Predicting survival in malignant pleural effusion: development and validation of the lent prognostic score. Thorax 2014. Published Online First. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McPherson GC, Campbell MK, Elbourne DR. Investigating the relationship between predictability and imbalance in minimisation: a simulation study. Trials 2013;14:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee YC, Baumann MH, Maskell NA et al. Pleurodesis practice for malignant pleural effusions in five English-speaking countries: survey of pulmonologists. Chest 2003;124:2229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boshuizen RC, Thomas R, Lee YC. Advantages of indwelling pleural catheters for management of malignant pleural effusions. Curr Respir Care Rep 2013;2:93–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.