Abstract

Background

There is a need for simple clinical tools that can objectively assess fall risk in people with dementia. Wearable sensors seem to have potential for fall prediction, however, there has been limited work performed in this important area.

Objective

To explore the validity of sensor-derived physical activity (PA) parameters for predicting future falls in people with dementia. To compare sensor-based fall risk assessment with conventional fall risk measures.

Methods

A cohort study of people with confirmed dementia discharged from a geriatric rehabilitation ward. PA was quantified using 24-hour motion-sensor monitoring at the beginning of the study. PA parameters (percentage of walking, standing, sitting, lying; duration of single walking, standing, and sitting bouts) were extracted using specific algorithms. Conventional assessment included performance-based tests (Timed-up-and-go test, Performance-Oriented-Mobility-Assessment, 5-chair stand) and questionnaires (cognition, ADL-status, fear of falling, depression, previous faller). Outcome measures were fallers (at least one fall in the 3-month follow-up period) versus non-fallers.

Results

Seventy-seven people were included in the study (age 81.8 ± 6.3; community dwelling 88%, institutionalized 12%). Surprisingly, fallers and non-fallers did not differ on any conventional assessment (p= 0.069–0.991), except for ‘previous faller’ (p= 0.006). Interestingly, several PA parameters discriminated between groups. The ‘walking bouts average duration’, ‘longest walking bout duration’ and ‘walking bouts duration variability’ were lower in fallers, compared to non-fallers (p= 0.008–0.027). The ‘standing bouts average duration’ was higher in fallers (p= 0.050). Two variables, ‘walking bouts average duration’ [odds ratio (OR) 0.79, p= 0.012] and ‘previous faller’ [OR 4.44, p= 0.007] were identified as independent predictors for falls. The OR for a ‘walking bouts average duration’ of less than 15 seconds for predicting fallers was 6.30 (p= 0.020). Combining ‘walking bouts average duration’ and ‘previous faller’ improved fall prediction [OR 7.71, p< 0.001, sensitivity/specificity 72%/76%].

Discussion

Results demonstrate that sensor-derived PA parameters are independent predictors of fall risk and may have higher diagnostic accuracy in persons with dementia compared to conventional fall risk measures. Our findings highlight the potential of telemonitoring technology for estimating fall risk. Results should be confirmed in a larger study and by measuring PA over a longer time period.

Keywords: fall prediction, body worn sensor, physical activity, dementia

INTRODUCTION

Falls are a significant cause of injuries, loss of confidence, institutionalization and mortality in all older people [1,2], but particularly in those with dementia [3,4]. Their risk of falling is 3-fold higher compared to cognitively intact subjects [5]. When falling, they have a 3- to 4-fold risk of severe fall-related injuries such as hip fractures [6]. People with dementia recover less well after a fall than those without dementia [7]. In view of the suffering caused by such falls, and the enormous cost of caring for people with dementia who have fallen, there is an urgent need to optimize the prevention of falls in this group.

Among various predictors for falls in the population with dementia (i.e., disease specific motor impairment, type and severity of dementia, behavioral disturbances, functional impairment, and neuroleptics [8]), physical activity (PA) level has been identified as one important and potentially modifiable fall risk factor [5,9,10]. Some studies have found higher levels of PA to be protective against falling [9] whereas others have reported dementia-specific PA characteristics (i.e., wandering, agitated behavior) as fall predictors [5,10]. Existing fall-prediction studies in people with dementia have used subjective questionnaire-based PA assessment [9,11] which may not allow accurate discrimination between ‘protective’ or ‘risk’ PA pattern. Objective monitoring of PA characteristics in person with dementia and exploration of their relationship with falling is needed to better understand and design effective interventions for this population [11].

In recent years, body wearable sensor technology based on electro-mechanical sensors has provided a new avenue for objectively detecting and monitoring body motion and PA of individuals under natural conditions [12,13]. Wearable sensors have the benefits of portability and low-cost, making these devices relevant to real-world fall risk assessment [14,15]. Since many falls occur in the home and community, where hazards are commonplace, it has been suggested to assess fall risk in these complex “natural” environments [16,17]. Further, there are significant concerns that people working in busy clinical settings do not have the time or equipment required to perform thorough objective fall risk assessments [18], and even where possible, these clinical settings do not emulate the natural home and community environment [16,17]. Additionally, fall risk assessment based on performance-based tests may be insensitive in those with cognitive impairment [19,20]. There is a need for simple clinical tools that can objectively assess fall risk in the rapidly growing population of cognitively impaired [18,21]. However, to date, there has been limited work performed in this important area [18,21,22].

A recent systematic review on wearable sensors-based fall prediction highlighted important shortcomings including (a) lack of prospective fall risk assessment, (b) lack of studies in more specialized high-risk populations such as those with dementia, and (c) lack of comparison between wearable sensor-based assessments and current clinical assessments for demonstrating benefits of the new sensor-based methods [22]. Importantly, the existing studies captured sensor data during in-clinic assessments such as the Timed-up-and-go test [23,24] or gait analysis [25] which require a specific test routine or laboratory setting. To our knowledge, no study explored the accuracy of sensor data captured in an everyday environment for prediction of future falls in people with dementia.

The aim of this study was to explore the validity of sensor-derived PA parameters quantified within a natural environment for predicting future falls in people with dementia. A second aim was to compare the validity of sensor-based fall risk assessment with conventional fall risk measures.

METHODS

Sample

Participants were recruited from rehabilitation wards of a geriatric hospital (AGAPLESION Bethanien-Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany) at the end of rehabilitation. In individuals who met inclusion criteria for cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Examination, MMSE [26], score 17–26), a dementia diagnosis was confirmed according to international standards [27,28]. Diagnosis was based on medical history, clinical examination, cerebral imaging, established neuropsychological test battery (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease [29]), and the Trail Making Test [30]. Further inclusion criteria were written informed consent; approval by the legal guardian (if appointed); aged 65 and older; no uncontrolled or terminal neurological, cardiovascular, metabolic, or psychiatric disorder. The study was approved by the Medical Department of the University of Heidelberg Ethics Committee in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Descriptive Measures

Age, gender, cognitive performance (MMSE) [26], activities of daily living (ADL, Barthel Index) [31], fear of falling (Falls Efficacy Scale-International, FES-I) [32], depression (Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia) [33], comorbidity (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, CIRS) [34], and previous falls (in the last year, retrospective documentation) as obtained by self-report.

Performance-based assessment of functional status

Performance-Oriented-Mobility-Assessment (POMA)

The POMA [35] is a reliable and valid clinical test to assess gait and mobility deficits in specified motor tasks, related to risk of falling (i.e., rising from a chair, standing balance, turning, initiating gait, sitting down) in older adults and patient populations [36]. The total score range is 0–28 with higher values indicating better performance. An experienced therapist instructed the participants how to perform the maneuvers, supervised the participants, and scored each participant’s performance.

Timed-up-and-go-test (TUG)

The TUG [37] was used to test participants’ basic functional mobility. The TUG is a reliable and valid clinical test to quantify mobility performance by timing participants with a stopwatch while rising from an armchair, walking 3 meters, turning, walking back, and sitting down.

5-chair stand

The 5-chair stand test is an established functional assessment in older adults, measuring the time required (in seconds) to complete 5 repeated chair stands [38]. Participants were asked to stand up five times from the initial sitting position as quickly as possible.

Physical activity assessment

PA was quantified during a 24-hour period by a motion-sensor (Physilog [13]) attached to the chest with an elastic belt. Patients were visited at home for attaching/detaching the sensor. All measures were conducted during a weekday. The Physilog system (BioAGM, CH) is a small (95×60×22mm), light (122g), long-term recording system containing inertial sensors (two accelerometers and one gyroscope) with software developed to identify postural positions and movements such as walking, standing, sitting, or lying [12,13,15]. A walking period was defined as an interval with at least 3 successive steps as described in the validation study of the Physilog [13]. Activities with less than 3 steps were considered as standing (e.g. working in the kitchen and moving less than 3 steps). The analysis algorithm is described elsewhere in detail [13]. It has proven to be sensitive (87–99%) and specific (87–99.7%) for detection of PA pattern in different samples of older adults and patients [12,13,15,39].

Nine PA parameters were calculated which represent characteristics of walking, standing, sitting and lying: 1) walking during 24 hours, %; 2) average duration of all walking bouts conducted during the 24- hour measurement (= walking bouts average duration), sec; 3) duration of the longest walking bout (= longest walking bout duration), sec; 4) variability of the duration of walking bouts as calculated by the coefficient of variation, CV, (= walking bouts duration variability), %; 5) standing during 24 hours, %; 6) standing bouts average duration, sec; 7) sitting during 24 hours, %; 8) sitting bouts average duration, sec; 9) lying during 24 hours, %.

Assessment of falls

All study participants were monitored for falls for 3 months after the initial baseline assessment. Fall calendars were sent to the participants with written instructions and a prepaid return envelope to return the calendar every month. Phone calls were used to remind the participants of missing calendar fall logs. A fall was defined as “an unexpected event in which the participants come to rest on the ground, floor, or lower level” [40]. Following a previous fall prediction study in people with dementia [19] the 3-month follow-up period was chosen in an attempt to be long enough to capture fall occurrences but not so long that the progression of the dementia could be a confounding factor.

Statistical analysis

Each participant was dichotomously categorized as a ‘non-faller’ or a ‘faller’ (at least one fall in a 3-month follow-up period). The means, SD and range were calculated, for non-fallers and fallers, for each of the variables reported in the present study. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate the validity of variables to discriminate between non-fallers and fallers due to non-normal distribution of several continuous variables. Chi-square tests were used for dichotomous variables.

Logistic regression analysis was employed to examine the relationship between each study variable and risk of falling. First, univariate logistic regression was employed to investigate the relationship of the test variables using ‘faller/non-faller’ as the dependent variable. This strategy reflects the exploratory character of the study. The odds ratio (OR) and coefficient of determination (R2) were calculated for each explanatory variable. All variables were treated as continuous except “previous faller” which was treated dichotomously (yes/no). Second, stepwise multivariate logistic regression, using the variables found to be significantly associated in the univariate analysis, was performed to investigate the independent effects of variables in predicting fallers. The receiver operating curve (ROC) and area under the curve (AUC) were calculated for different fall-prediction models. Sensitivities and specificities for different cut-off values were calculated for non-categorical variables shown to have an independent effect on predicting fallers. A two-sided p-value≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistics 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

One hundred and eighteen people were asked to participate in the study. Of these, 115 (97.5%) agreed to take part. The 3 (2.5%) who declined did so because they did not like the idea of wearing the activity sensor. Another 6 participants (5.2%) removed the activity sensor before the end of the 24 hours period and were excluded from the analysis.

Seventy-seven participants (67.0%) completed the study at 3 month. Three died (2.6%) and 29 (25.2%) did not complete the calendar-based fall documentation and were excluded from the analysis. The sample population comprised older adults (age 81.8 ± 6.3 years) with impaired cognitive (MMSE score 22.1 ± 3.2) and functional (Barthel Index score 82.7 ± 14.2; POMA score 21.0 ± 4.5) status. Participants had been discharged from a geriatric rehabilitation ward. Reasons for rehabilitation were: cerebrovascular diseases: 15.7%; lower limb fractures: 13.7%; other fracture: 11.8%; heart disease: 11.8%; miscellaneous diagnoses including genitourinary, digestive, neoplasm, respiratory: 47.0%. During the time of PA assessment, sixty-eight participants (88.3%) were living independently at home, partly with supportive care; 9 (11.7%) were institutionalized. Twenty-eight participants (36.4%) had fallen during the three month follow-up period.

Validity of variables to discriminate between fallers and non-fallers

Comparison of study variables between fallers and non-fallers are displayed in Table 1. Fallers and non-fallers did not significantly differ for age, gender, cognitive status, ADL status, depression, comorbidities, or living situation (community dwelling vs. institutionalized) (p= 0.069–0.991). Participants who fell during the 3-month observation period had significantly fallen more often in the last year (fallers: 75%, non-fallers: 42.9%, p= 0.006).

Table 1.

Differences between fallers and non-fallers for descriptive variables, performance-based tests, and physical activity parameters

| Variable | Fallers (n=28) |

Non-Fallers (n=49) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive variables | |||

| Age, years | 82.0 ± 7.1 | 81.8 ± 5.9 | 0.836 |

| Male, % | 21.4 | 34.7 | 0.221 |

| Mini Mental State Examination, score | 22.0 ± 3.4 | 22.1 ± 3.1 | 0.919 |

| Barthel Activities of daily living, score | 81.6 ± 16.4 | 83.2 ± 12.9 | 0.991 |

| Falls Efficacy Scale-International, score | 26.3 ± 8.6 | 27.0 ± 8.7 | 0.815 |

| Cornell Scale for Depression, score | 7.0 ± 4.7 | 5.3 ± 4.4 | 0.069 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, score | 24.0 ± 3.6 | 24.2 ± 3.4 | 0.682 |

| Previous fall (last year), % | 75.0 | 42.9 | 0.006* |

| Living situation, % | |||

| Community dwelling | 85.7 | 89.8 | 0.592 |

| Institutionalized | 14.3 | 10.2 | |

| Performance-based tests | |||

| Timed-up-and-go test, sec | 13.3 ± 5.9 | 14.3 ± 5.4 | 0.236 |

| Performance-Oriented-Mobility-Assessment, score | 21.0 ± 4.3 | 21.0 ± 4.7 | 0.928 |

| 5-chair stand, sec | 15.9 ± 6.9 | 15.2 ± 4.0 | 0.553 |

| Physical activity parameters | |||

| Walking | |||

| Walking during 24 hours, % | 4.1 ± 3.1 | 4.9 ± 2.8 | 0.117 |

| Walking bouts average duration, sec | 10.7 ± 2.3 | 13.5 ± 5.2 | 0.008* |

| Longest walking bout duration, sec | 89.9 ± 100.2 | 200.5 ± 281.7 | 0.009* |

| Walking bouts duration variability, CV, % | 87.1 ± 35.5 | 126.5 ± 80.1 | 0.027* |

| Standing | |||

| Standing during 24 hours, % | 14.0 ± 7.9 | 12.0 ± 6.1 | 0.403 |

| Standing bouts average duration, sec | 51.1 ± 30.4 | 40.8 ± 11.9 | 0.050* |

| Sitting | |||

| Sitting during 24 hours, % | 38.8 ± 14.4 | 39.5 ± 10.5 | 0.857 |

| Sitting bouts average duration, sec | 583.7 ± 309.6 | 618.4 ± 314.8 | 0.703 |

| Lying | |||

| Lying during 24 hours, % | 43.1 ± 10.2 | 43.7 ± 10.8 | 0.983 |

CV= coefficient of variation,

p-value≤ 0.05

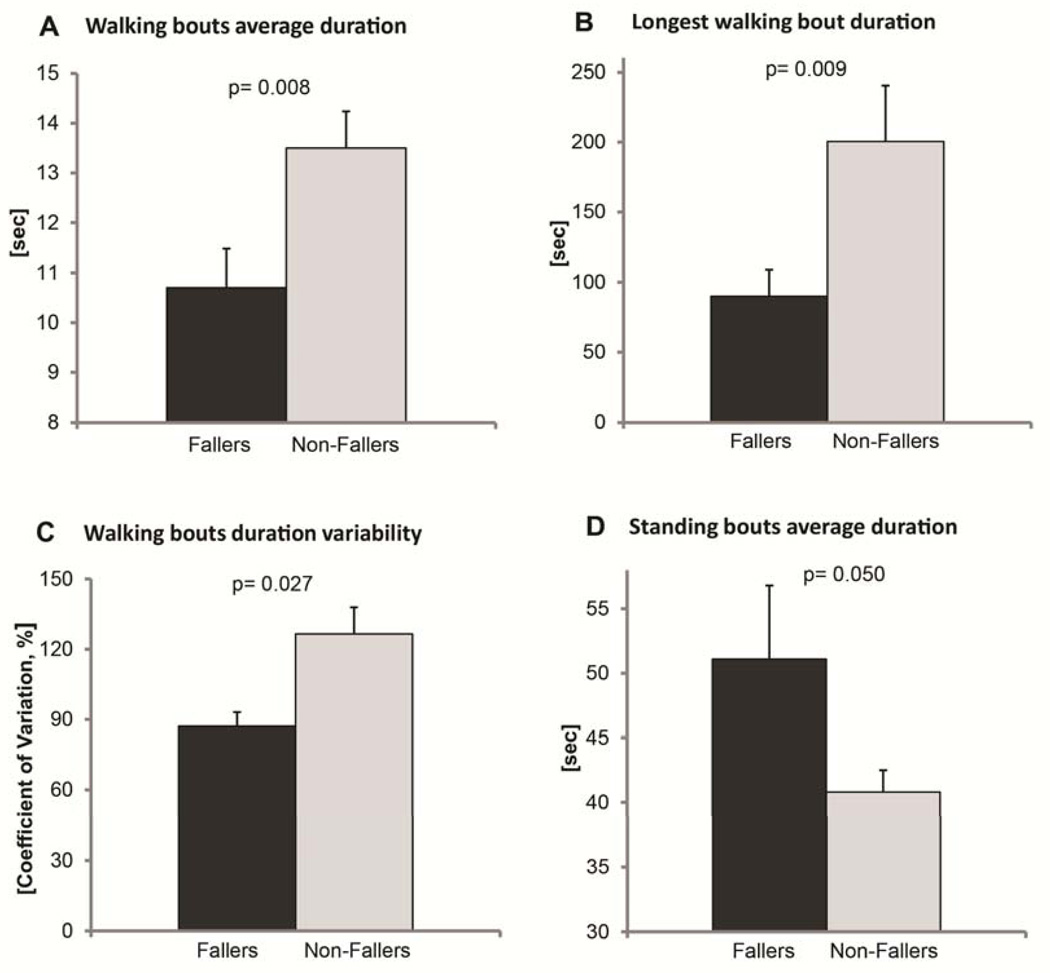

Surprisingly, no significant differences between fallers and non-fallers were obtained for performance-based tests (p= 0.236–0.928). In contrast, significant differences between both groups were obtained for sensor-based PA parameters related to walking and standing. The ‘walking bouts average duration’ was lower in fallers (mean: 10.7 ± 2.3 sec) compared to non-fallers (mean: 13.5 ± 5.2 sec, p= 0.008, Figure 1A). The ‘longest walking bout duration’ was shorter in fallers (mean: 89.9 ± 100.2 sec) compared to non- fallers (mean: 200.5 ± 281.7 sec, p= 0.009, Figure 1B). The ‘walking bouts duration variability’ was lower in fallers (CV mean: 87.1 ± 35.5%) compared to non-fallers (CV mean: 126.5 ± 80.1%, p= 0.027, Figure 1C). Interestingly, fallers had a higher ‘standing bouts average duration’ (mean: 51.1 ± 30.4 sec) compared to non-fallers (mean: 40.8 ± 11.9 sec, p= 0.050, Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Sensor-derived physical activity parameters related to walking (A, B, C) and standing (D) discriminated between fallers and non-fallers with dementia (mean ± standard error)

Predictor variables for falls

In the univariate regression analysis, four variables were significantly associated with the risk of falling in the next 3 months: ‘previous faller’, ‘walking bouts average duration’, ‘longest walking bout duration’ and ‘walking bout duration variability’ (Table 2). The best-fit model was found for ‘walking bouts average duration’ (R2 = 0.156).

Table 2.

Results of univariate logistic regression

| Variable | R2 | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.000 | 1.003 | 0.931–1.081 | 0.931 |

| Male, % | 0.027 | 0.513 | 0.175–1.508 | 0.225 |

| Mini Mental State Examination, score | 0.001 | 0.981 | 0.849–1.133 | 0.793 |

| Barthel Activities of daily living, score | 0.004 | 0.992 | 0.960–1.025 | 0.620 |

| Falls Efficacy Scale-International, score | 0.002 | 0.991 | 0.939–1.047 | 0.758 |

| Cornell Scale for Depression, score | 0.045 | 1.087 | 0.979–1.206 | 0.117 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, score | 0.001 | 0.983 | 0.860–1.123 | 0.800 |

| Previous fall (last year), % | 0.130 | 4.000 | 1.434–11.155 | 0.008 |

| Timed-up-and-go-test, sec | 0.011 | 0.966 | 0.883–1.056 | 0.442 |

| Performance-Oriented-Mobility-Assessment, score | 0.000 | 1.002 | 0.904–1.111 | 0.966 |

| 5-chair stand, sec | 0.005 | 1.023 | 0.937–1.118 | 0.612 |

| Walking during 24 hours, % | 0.024 | 0.905 | 0.762–1.075 | 0.255 |

| Walking bouts average duration, sec | 0.156 | 0.792 | 0.662–0.949 | 0.011 |

| Longest walking bout duration, sec | 0.112 | 0.995 | 0.991–1.000 | 0.041 |

| Walking bouts duration variability, CV, % | 0.129 | 0.987 | 0.975–.9998 | 0.022 |

| Standing during 24 hours, % | 0.220 | 1.044 | 0.975–1.119 | 0.220 |

| Standing bouts average duration, sec | 0.077 | 1.027 | 0.997–1.058 | 0.076 |

| Sitting during 24 hours, % | 0.001 | 0.994 | 0.952–1.038 | 0.798 |

| Sitting bouts average duration, sec | 0.004 | 1.000 | 0.998–1.001 | 0.637 |

| Lying during 24 hours, % | 0.001 | 0.995 | 0.952–1.040 | 0.831 |

CV= coefficient of variation

Two variables, ‘previous faller’ [adjusted OR 4.44 (95% CI 1.51–13.09; p= 0.007)] and ‘walking bouts average duration’ [adjusted OR 0.79 (95% CI 0.66–0.95; p= 0.012)] remained in the multivariate model (R2= 0.276) suggesting that these two variables are independent predictors. We checked the multivariate logistic regression analysis using the ‘methods = enter’ methodology and the results were similar, with no other variable having an independent significant effect in predicting fallers.

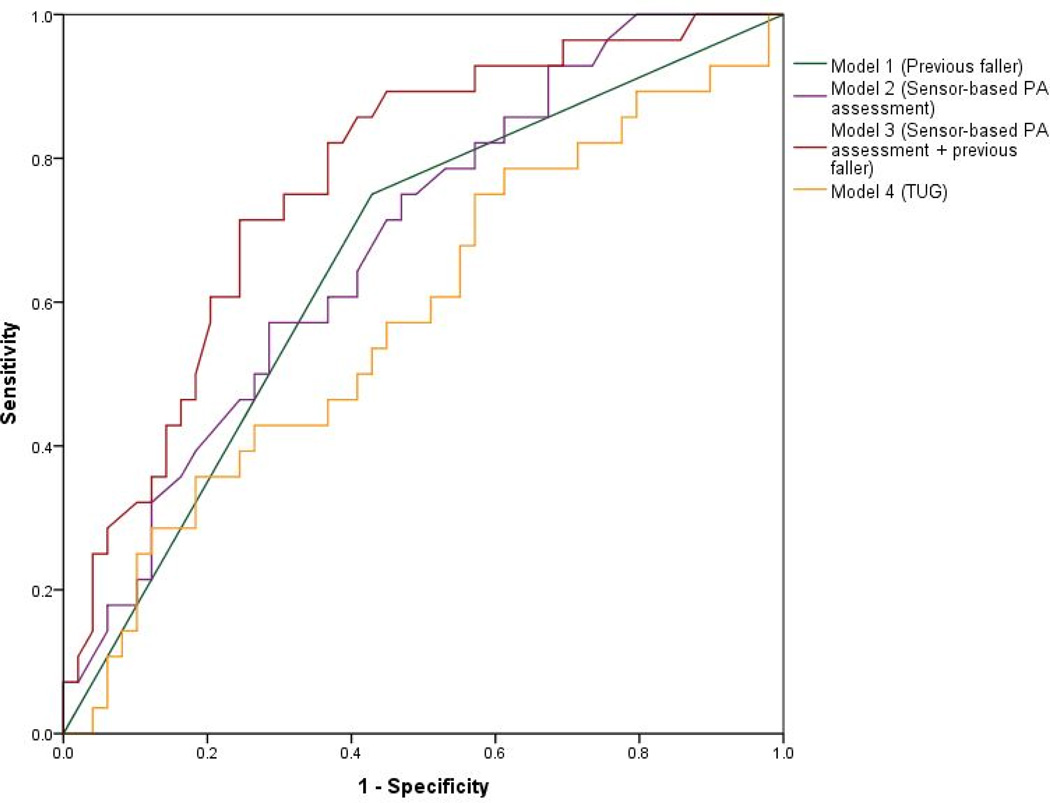

Four models for prospective fall prediction were calculated. Model 1 using ‘previous faller’, Model 2 using ‘walking bouts average duration’, and Model 3 using a combination of ‘previous faller’ and ‘walking bouts average duration’. Model 4 uses the TUG for comparing results of performance-based tests with the sensor-based fall risk assessment. The ROCs for the four models are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating curves of different models for predicting future falls in people with dementia. Model 1 uses ‘previous faller’ data (AUC 0.661). Model 2 uses the ‘walking bouts average duration’ obtained by the physical activity (PA) sensor (AUC 0.684). Model 3 combines ‘previous faller’ and ‘walking bouts average duration’ (AUC 0.771). Model 4 uses timed-up-and-go (TUG) results (AUC 0.582)

The AUC for Model 1 (‘previous fallers’) was 0.661 (95% CI 0.535–0.786; p= 0.020) with a sensitivity of 75.0% and specificity 57.1% for predicting future falls.

The AUC for Model 2 (“walking bouts average duration”) was 0.684 (95% CI 0.564–0.803; p= 0.008). The sensitivities and specificities for different cut-off values for Model 2 are displayed in Table 3. A cut-off of 15 sec gives 93% sensitivity, but low specificity (33%). A cut-off of 8 sec gives 93% specificity but the sensitivity is considerably reduced (14.3%). The OR for predicting fallers ranged between 1.96 and 6.30 depending on the cut off value (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sensitivities, specificities, odds ratios (+95% CIs) [p] of different cut-offs for the ‘walking bouts average duration’

| Cut-offs (sec) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 14.3 | 93.3 | 2.56 (0.53–12.36) [0.243] |

| 9 | 21.4 | 87.8 | 1.96 (0.56–6.77) [0.291] |

| 10 | 39.3 | 81.6 | 2.88 (1.01–8.20) [0.048] |

| 11 | 60.7 | 61.2 | 2.44 (0.94–6.32) [0.066] |

| 12 | 78.6 | 46.9 | 3.24 (1.12–9.39) [0.030] |

| 13 | 82.1 | 38.8 | 2.91 (0.95–8.97) [0.062] |

| 14 | 89.3 | 32.7 | 4.04 (1.06–15.4) [0.041] |

| 15 | 92.9 | 32.7 | 6.30 (1.33–29.91) [0.020] |

The highest AUC (0.771, 95% CI 0.664–0.878; p≤ 0.001) was obtained by Model 3 combining “previous faller” and “walking bouts average duration”.

Using a cut-off value for ‘walking bouts average duration’ of <15 sec combined with a previous history of falls the sensitivity was 71.5% and the specificity 75.5%. The OR for experiencing a fall in the following 3 month was 7.71 (95% CI 2.71–21.96, p< 0.001). The lowest AUC (0.582, 95% CI 0.447–0.716; p= 0.236) was obtained for Model 4 using the TUG.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the discriminative and predictive validity of sensor-derived PA parameters for identifying future falls in people with confirmed mild to moderate dementia. Present results suggest that traditional performance-based tests are insensitive predictors of fall risk, whereas PA parameters related to walking and standing are useful fall risk indicators. To our knowledge, this is the first study which used objective PA monitoring for predicting falls in people with dementia. Our findings suggest that analysis of everyday motions using wearable sensors can enhance accuracy of traditional fall risk assessment in high risk populations such as people with dementia.

Validity of variables to discriminate between fallers and non-fallers

None of the demographic data, performance-based tests, and questionnaires, except ‘previous fallers’, discriminated between future fallers and non-fallers. Our findings confirm results of a previous study in people with dementia in which only previous falls but not performance-based tests and demographic data did predict future falls (4-month follow-up period) [19]. Reliability of performance-based can be affected by dementia-associated symptoms such as impaired executive function, memory, and attention [20], which may explain insufficient validity of these measures for predicting falls. But even in cognitively intact older adults, performance-based tests such as TUG may have only poor to moderate accuracy for predicting future falls as highlighted in a recent systematic review [41].

Results of this study demonstrate that fallers and non-fallers differ in physical activity pattern. On the same note, the present results suggest that measuring the overall daily walking time is not an accurate parameter for discriminating between fallers and non-fallers. In contrast, specific walking characteristics such as the duration of walking bouts were found to be sensitive discriminators. Interestingly, some PA characteristics were protective (long walking bouts) whereas others increased risk of falling (long standing bouts). The longest bout walked during the 24-hour measurement was only half as long in fallers compared to non-fallers and a sensitive discriminator. On average, duration of walking bouts was significantly shorter in fallers compared to non-fallers.

PA behavior is affected by personal, social, and environmental factors [42]. We can only speculate about the factors accounting for the differences in PA characteristics between both groups. Differences were not related to socio-demographics or clinical status. Importantly, functional performances as quantified by the tests used in this study did not explain the differences in walking characteristics. A poor relationship between functional performances and PA level in older adults has been reported previously [43].

Our findings suggest that fallers had a more interrupted walking pattern, with short walking bouts rather than continuously long walking bouts. Results could indicate less direct and more inefficient travel pattern in fallers, potentially related to disorientation or wandering behavior (i.e., random travel, and pacing) as described in previous studies [44]. Also, dementia-associated dual-task deficits (i.e., limited ability to walk with a concurrent task [45]) may have accounted for shorter walking bouts found in fallers.

The lack of long walking bouts in the daily activity profile of fallers may also indicate limited outdoor walking. Fallers may have walked predominately in indoor spaces as indicated by shorter walking bouts. Results may suggest that more fallers were housebound when compared to non-fallers, potentially due to environmental barriers (i.e., inability to climb stairs) or lack of support for outdoor or longer range activities by a caregiver/relative. Being housebound and above the age of 75 has been previously identified as a risk factor of falling indoors [46].

The shorter walking bouts found in fallers in the present study could be related to previous falls. Future fallers had significantly more previous falls, as found in previous studies in people with dementia [9,19]. In the present study, previous falls may have caused changes in walking characteristics, potentially due to fear of falling. Since we did not find any differences in fear of falling between fallers and non-fallers based on self-report (FES-I), our results may indicate differences in self-report and observed functioning (walking) as reported in previous studies [47].

The variability in duration of all walking bouts in 24-hours was significantly higher in non-fallers compared to fallers and was identified as a sensitive discriminative parameter. The increased variability indicates that non-fallers had a more diverse PA pattern including both short and long walking bouts over the course of the day. A diversity of activities has been previously described as protective against falls [46].

Interestingly, fallers had significantly longer standing bouts compared to non-fallers. As per algorithm, standing includes phases of standing as well as walking less than 3 steps. Walking a few steps and standing again could indicate fidgety, restlessness and agitation as common dementia-associated behavioral symptoms, which have been linked to increased fall risk [8]. Subtle dementia-associated impairments in postural control [48], not detected by the performance-based test, may explain increased fall risk during phases of prolonged standing and fidgeting as obtained in the present study. Our results may indicate that such fall-risk related activity behavior could be quantified in an everyday environment using wearable sensors.

For individuals who are already fall-prone, increased activity may result in a greater risk of falling due to increased exposure to environmental hazards [49]. If walking is considered as the ‘exposure’ to fall risk in our study, results may indicate that fallers had less exposure and yet they still fell more. This may suggest that specific PA pattern such as short walking bouts or prolonged phases of standing are more sensitive indicators of fall risk, compared to estimating exposure by overall time of walking.

Predictor variables for falls

The results of the regression analysis suggest that, out of the various PA variables examined, the ‘walking bouts average duration’ performed the best in predicting falls in older adults with dementia. Each second of shorter ‘walking bouts average duration’ was associated with a 26% increased chance of becoming a faller. Someone with a ‘walking bouts average duration’ of more than 15 seconds is very unlikely to fall. Someone with a ‘walking bouts average duration’ of less than 15 seconds had a 6.3 times increased fall chance compared to someone above this threshold. Using this cutoff, the sensitivity is 93%, however, the specificity is only 33%, implying that it will predict most of the future falls, but will falsely predict falls in 77% of non-fallers. Thus, while this variable is not a standalone candidate for fall prediction, it could add precision to a fall index.

Combining the independent predictors ‘walking bouts average duration’ and ‘previous faller’ improved fall prediction to a clinically useful level. A ‘walking bouts average duration’ of less than 15 sec combined with a previous history of falls gave a sensitivity of 72% and a specificity of 76%. Intervening on these individuals would represent reasonable targeting as only 24% of people measured at high risk would not have subsequently fallen.

Only a few studies sought to prospectively predict falls using wearable sensors [23,24]. Marschollek et al. [24] followed-up 50 geriatric patients for one year after instrumented TUG and gait assessment. In that study, an AUC of 0.65 was reported based on accelerometer-derived parameters classified using logistic regression [24], which is comparable with our fall prediction Model 2 using sensor data only (‘walking bouts average duration’, AUC 0.68). Interestingly, in Marschollek et al’s. study predictive performance was increased when accelerometer data were combined with PA questionnaire data (AUC 0.72), whereas a high activity level was associated with low fall risk. Predictive validity of this combined model is comparable with our Model 3 combining sensor data and questionnaire data (‘previous faller’) (AUC 0.77).

Green et al. [23] reported a good validity (AUC 0.78) of instrumented TUG assessment for predicting future falls (2 years follow-up) in community dwelling older adults without cognitive impairment. Future studies need to investigate if similar results can be achieved in people with dementia.

In the present study, univariate analysis showed that some of the other PA variables (‘longest walking bout duration’, ‘walking bouts duration variability’) also had value in predicting falls, although they were inferior to the ‘walking bouts average duration’. The ‘walking bouts average duration’ includes elements of the other PA parameters studied. Someone walking long distances over the course of the day increases the ‘walking bouts average duration’ while walking both short distances and long distances increases the ‘walking bouts duration variability’. A high degree of correlation and co-linearity therefore would be expected between these PA parameters, which is why on multi-variable analysis, the other PA were no longer independent predictors.

Limitations and future directions

One obvious limitation of this study is the small sample size. However, we feel that this limitation does not invalidate our findings, given that the main aim of the study was to explore the association between PA pattern and future falling. Our proposed models must be validated in a larger sample size to evaluate their true predictive potential.

The battery life of the activity monitor used in the present study restricted the monitoring period to 24 hours. This assessment period did not cover day-to-day variability in PA, although PA behavior in older adults is less variable than in younger populations [50] and day-to-day reliability of PA assessment was high in a sample of older adults (> 60 years) [50]. The 24-hour monitoring in our study may therefore have been sufficient to document habitual PA because of low day-to-day variability. However, further research should address whether a longer period of monitoring increases the accuracy of fall prediction.

Increased standing bout duration was identified as a fall risk factor in the present study. As a limitation, the algorithm used in this study cannot discriminate between phases of quiet standing and walking very short bouts (< 3 steps). Further algorithm development could separate these phases to better understand their association with fall risk.

While we have identified novel objective fall-associated PA parameters, further studies are required to elucidate their bio-psycho-social interpretation in the context of fall risk assessment. Dementia-specific behavioral symptoms such as wandering or agitation should be assessed by standardized instruments [51,52] for examining their association with the fall-risk related PA pattern found in this study. More accurate assessments including spatio-temporal gait analysis [25] and dual-task assessment [45] should be used for measuring dementia-specific motor-cognitive deficits, potentially accounting for the fall risk related PA pattern found in this study (i.e., short walking bouts). Further, the association between fall risk related PA behavior and environmental barriers in the home and immediate outdoor environment need to be quantified in future studies, for instance by using the Housing Enabler instrument [53].

In our study accuracy of the reported level of fear of falling (FES-I) may have been influenced by difficulty in comprehending questions or reporting on subjective states, as discussed previously [54]. Future studies may use the Iconographical Falls Efficacy Scale using pictures as visual cues and previously validated in the cognitively impaired [54].

We observed a high rate of falling (36.4% of subjects) during a relatively brief follow-up (3 months). Future studies should investigate whether non-fallers as identified by the presented short-term fall prediction approach become fallers during a longer follow-up period.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that the combination of PA monitoring and fall history has potential to provide a clinically meaningful surveillance of people with dementia at high risk of falling. This information could be used to provide targeted fall prevention interventions. Present findings may help to design mHealth technologies using monitoring of everyday activities for the purpose of fall risk assessment in people with dementia.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by an STTR-Phase II Grant (Award Number 2R42AG032748) from the National Institute on Aging, a postdoctoral research fellowship of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the Baden-Wuerttemberg Stiftung, the Robert Bosch Stiftung, and the Dietmar Hopp Stiftung. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding institutions. We thank Marilyn Gilbert for critical revision of the manuscript (interdisciplinary Consortium on Advanced Motion Performance, University of Arizona).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Michael Schwenk, Prof. Klaus Hauer, Dr. Tania Zieschang, Stefan Englert, Prof. Jane Mohler, and Dr. Bijan Najafi report no conflict of interest or any financial support received.

Author Contributions: Michael Schwenk: Development of concept and design, study management, acquisition of participants, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript. Klaus Hauer: Development of concept and design, acquisition of participants, study management. Tania Zieschang: Acquisition of participants, study management. Stefan Englert: Statistical analysis. Bijan Najafi: Development of concept and design, analysis of physical activity data, statistical analysis. All authors including Jane Mohler contributed to interpretation of data, drafting the article, and final approval of the version to be published.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, Doucette JT. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA the journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273:1348–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinetti ME, Williams CS. Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. New England journal of medicine. 1997;337:1279–1284. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710303371806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris JC, Rubin EH, Morris EJ, Mandel SA. Senile dementia of the alzheimer’s type:. An important risk factor for serious falls. Journal of gerontology. 1987;42:412–417. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Doorn C, Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S, Richard Hebel J, Port CL, Baumgarten M, Quinn CC, Taler G, May C, Magaziner J. Dementia as a risk factor for falls and fall injuries among nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1213–1218. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchner DM, Larson EB. Falls and fractures in patients with alzheimer-type dementia. JAMA. 1987;257:1492–1495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord SR, Sherrington C, Menz HB. Falls in older people. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw FE. Falls in cognitive impairment and dementia. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2002;18:159–173. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(02)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Härlein J, Dassen T, Halfens RJ, Heinze C. Fall risk factors in older people with dementia or cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Journal of advanced nursing. 2009;65:922–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allan LM, Ballard CG, Rowan EN, Kenny RA. Incidence and prediction of falls in dementia: A prospective study in older people. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz IR, Rupnow M, Kozma C, Schneider L. Risperidone and falls in ambulatory nursing home residents with dementia and psychosis or agitation: Secondary analysis of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2004;12:499–508. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suttanon P, Hill KD, Said CM, Dodd KJ. A longitudinal study of change in falls risk and balance and mobility in healthy older people and people with alzheimer disease. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2013;92:676–685. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318278dcb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Najafi B, Armstrong DG, Mohler J. Novel wearable technology for assessing spontaneous daily physical activity and risk of falling in older adults with diabetes. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2013;7:1147–1160. doi: 10.1177/193229681300700507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Najafi B, Aminian K, Paraschiv-Ionescu A, Loew F, Bula CJ, Robert P. Ambulatory system for human motion analysis using a kinematic sensor: Monitoring of daily physical activity in the elderly. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2003;50:711–723. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2003.812189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aminian K, Najafi B. Capturing human motion using body-fixed sensors:. Outdoor measurement and clinical applications. Computer Animation and Virtual Worlds. 2004;15:79–94. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Najafi B, Aminian K, Loew F, Blanc Y, Robert PA. Measurement of stand-sit and sit-stand transitions using a miniature gyroscope and its application in fall risk evaluation in the elderly. Ieee Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2002;49:843–851. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2002.800763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lord SR, Menz HB, Sherrington C. Home environment risk factors for falls in older people and the efficacy of home modifications. Age and Ageing. 2006;35 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss A, Brozgol M, Dorfman M, Herman T, Shema S, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Does the evaluation of gait quality during daily life provide insight into fall risk? A novel approach using 3-day accelerometer recordings. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2013;27:742–752. doi: 10.1177/1545968313491004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shany T, Redmond SJ, Marschollek M, Lovell NH. Assessing fall risk using wearable sensors: A practical discussion. A review of the practicalities and challenges associated with the use of wearable sensors for quantification of fall risk in older people. Zeitschrift fur Gerontologie und Geriatrie. 2012;45:694–706. doi: 10.1007/s00391-012-0407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrell MK, Rutt RA, Lusardi MM, Williams AK. Are scores on the physical performance test useful in determination of risk of future falls in individuals with dementia? Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy. 2011;34:57–63. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0b013e318208c9b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauer K, Oster P. Measuring functional performance in persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:949–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shany T, Redmond SJ, Narayanan MR, Lovell NH. Sensors-based wearable systems for monitoring of human movement and falls. Sensors Journal, IEEE. 2012;12:658–670. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howcroft J, Kofman J, Lemaire ED. Review of fall risk assessment in geriatric populations using inertial sensors. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation. 2013;10:91. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-10-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greene BR, Doheny EP, Walsh C, Cunningham C, Crosby L, Kenny RA. Evaluation of falls risk in community-dwelling older adults using body-worn sensors. Gerontology. 2012;58:472–480. doi: 10.1159/000337259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marschollek M, Rehwald A, Wolf K, Gietzelt M, Nemitz G, Meyer Zu Schwabedissen H, Haux R. Sensor-based fall risk assessment-an expert’to go’. Methods of information in medicine. 2011;50:420. doi: 10.3414/ME10-01-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Senden R, Savelberg H, Grimm B, Heyligers I, Meijer K. Accelerometry-based gait analysis, an additional objective approach to screen subjects at risk for falling. Gait & posture. 2012;36:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease:. Report of the nincds-adrda work group under the auspices of department of health and human services task force on alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, Cummings JL, Masdeu JC, Garcia JH, Amaducci L, Orgogozo JM, Brun A, Hofman A, et al. Vascular dementia: Diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the ninds-airen international workshop. Neurology. 1993;43:250–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris JC, Mohs RC, Rogers H, Fillenbaum G, Heyman A. Consortium to establish a registry for alzheimer’s disease (cerad) clinical and neuropsychological assessment of alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:641–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oswald WD. Nuernberger altersinventar (nai) Goettingen: Hogrefe; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, Kempen G, Piot-Ziegler C, Todd C. Development and initial validation of the falls efficacy scale-international (fes-i) Age Ageing. 2005;34:614–619. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, Shamoian CA. Cornell scale for depression in dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23:271–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parmelee PA, Thuras PD, Katz IR, Lawton MP. Validation of the cumulative illness rating scale in a geriatric residential population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:130–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tinetti ME. Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb05480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kegelmeyer DA, Kloos AD, Thomas KM, Kostyk SK. Reliability and validity of the tinetti mobility test for individuals with parkinson disease. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1369–1378. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “up & go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guralnik J, Simonsick E, Ferrucci L, Glynn R, Berkman L, Blazer D, Scherr P, Wallace R. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. Journal of gerontology. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salarian A, Russmann H, Vingerhoets FJ, Burkhard PR, Aminian K. Ambulatory monitoring of physical activities in patients with parkinson’s disease. Biomedical Engineering, IEEE Transactions on. 2007;54:2296–2299. doi: 10.1109/tbme.2007.896591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hauer K, Lamb SE, Jorstad EC, Todd C, Becker C. Systematic review of definitions and methods of measuring falls in randomised controlled fall prevention trials. Age Ageing. 2006;35:5–10. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoene D, Wu SM, Mikolaizak AS, Menant JC, Smith ST, Delbaere K, Lord SR. Discriminative ability and predictive validity of the timed up and go test in identifying older people who fall: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:202–208. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benzinger P, Iwarsson S, Kroog A, Beische D, Lindemann U, Klenk J, Becker C. The association between the home environment and physical activity in community-dwelling older adults. Aging clinical and experimental research. 2014:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s40520-014-0196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicolai S, Benzinger P, Skelton DA, Aminian K, Becker C, Lindemann U. Day-today variability of physical activity of older adults living in the community. J Aging Phys Act. 2010;18:75–86. doi: 10.1123/japa.18.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martino-Saltzman D, Blasch BB, Morris RD, McNeal LW. Travel behavior of nursing home residents perceived as wanderers and nonwanderers. The Gerontologist. 1991;31:666–672. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.5.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camicioli R, Howieson D, Lehman S, Kaye J. Talking while walking the effect of a dual task in aging and alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1997;48:955–958. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.4.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bath PA, Morgan K. Differential risk factor profiles for indoor and outdoor falls in older people living at home in nottingham, uk. European journal of epidemiology. 1999;15:65–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1007531101765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feuering R, Vered E, Kushnir T, Jette AM, Melzer I. Differences between self-reported and observed physical functioning in independent older adults. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2013:1–7. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.828786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Franssen EH, Souren L, Torossian CL, Reisberg B. Equilibrium and limb coordination in mild cognitive impairment and mild alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:463. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb07240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tinetti ME. Prevention of falls and fall injuries in elderly persons: A research agenda. Preventive medicine. 1994;23:756–762. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rowe DA, Kemble CD, Robinson TS, Mahar MT. Daily walking in older adults: Day-to-day variability and criterion-referenced validity of total daily step counts. Journal of physical activity & health. 2007;4:434–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Algase DL, Beattie ER, Bogue E-L, Yao L. The algase wandering scale: Initial psychometrics of a new caregiver reporting tool. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias. 2001;16:141–152. doi: 10.1177/153331750101600301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Rosenthal AS. A description of agitation in a nursing home. Journal of gerontology. 1989;44:M77–M84. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.3.m77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iwarsson S, Slaug B. The housing enabler. An instrument for assessing and analysing accessibility problems in housing. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delbaere K, Close JCT, Taylor M, Wesson J, Lord SR. Validation of the iconographical falls efficacy scale in cognitively impaired older people. The Journals of Gerontology Series A. Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2013;68:1098–1102. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]