Abstract

Filippi syndrome is a rare, presumably autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by microcephaly, pre- and postnatal growth failure, syndactyly, and distinctive facial features, including a broad nasal bridge and underdeveloped alae nasi. Some affected individuals have intellectual disability, seizures, undescended testicles in males, and teeth and hair abnormalities. We performed homozygosity mapping and whole-exome sequencing in a Sardinian family with two affected children and identified a homozygous frameshift mutation, c.571dupA (p.Ile191Asnfs∗6), in CKAP2L, encoding the protein cytoskeleton-associated protein 2-like (CKAP2L). The function of this protein was unknown until it was rediscovered in mice as Radmis (radial fiber and mitotic spindle) and shown to play a pivotal role in cell division of neural progenitors. Sanger sequencing of CKAP2L in a further eight unrelated individuals with clinical features consistent with Filippi syndrome revealed biallelic mutations in four subjects. In contrast to wild-type lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs), dividing LCLs established from the individuals homozygous for the c.571dupA mutation did not show CKAP2L at the spindle poles. Furthermore, in cells from the affected individuals, we observed an increase in the number of disorganized spindle microtubules owing to multipolar configurations and defects in chromosome segregation. The observed cellular phenotypes are in keeping with data from in vitro and in vivo knockdown studies performed in human cells and mice, respectively. Our findings show that loss-of-function mutations in CKAP2L are a major cause of Filippi syndrome.

Main Text

Filippi syndrome (MIM 272440), also known as syndactyly type 1 with microcephaly and intellectual disability, belongs to the group of craniodigital syndromes. Affected individuals have short stature; microcephaly; a characteristic facial appearance with a bulging forehead, broad and prominent nasal bridge, and diminished alar flare; syndactyly; and intellectual disability as major phenotypic features.1 The first description of three of eight siblings born to healthy nonconsanguineous parents in an Italian family defined a previously unrecognized phenotype of facial dysmorphism, microcephaly, intellectual disability, cryptorchidism, pre- and postnatal growth retardation, speech impairment, syndactyly of the third and fourth fingers, clinodactyly of the fifth finger, and syndactyly of the second to fourth toes.2 Subsequent reported cases expanded the phenotypic spectrum to include visual disturbance, polydactyly, seizures, epilepsy, and ectodermal abnormalities, such as nail hypoplasia, long eyelashes, hirsutism, and microdontia.3–8 To date, a total of 28 affected individuals from 20 families have been reported worldwide.7–10 An autosomal-recessive mode of inheritance has been proposed on the basis of the similar number of affected male (19) and female (9) children observed in nonconsanguineous and consanguineous families.8,9 A range of investigations—including karyotyping, telomere analyses, fluorescence in situ hybridization for microdeletions at 22q11.2 and 16p13.3, and microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH)—did not reveal a specific genetic explanation.7,8,11,12 Recently, a female with a Filippi-like phenotype was reported with a heterozygous 10.4 Mb microdeletion in chromosomal region 2q24.3–q31.1.13 To our knowledge, a next-generation-sequencing-based approach has not been performed to elucidate the genetic cause of Filippi syndrome.9

Here, we report on a combined linkage and whole-exome sequencing (WES) approach applied to a Filippi-syndrome-affected family from Sardinia, an island with a long history of population isolation. Since the time of the first report on this family, a second affected child was born to the parents.8 The second child, also a boy, presents with a nearly identical phenotype to that of his older brother (Figure 1 and Table 1). Standard cytogenetic analysis, array CGH, and sequencing of GJA1 (MIM 121014) in the proband (FP1-1) did not reveal any genomic abnormalities.8 Hence, we performed genome-wide linkage analysis and WES to determine the genetic cause underlying the disorder in family FP1 after informed consent was given by the parents. We genotyped DNA from the proband, his brother, and his parents by using the Illumina HumanCoreExome-12 v.1.1 BeadChip according to the manufacturer’s protocol. We performed linkage analysis by assuming autosomal-recessive inheritance, full penetrance, consanguinity of second-degree cousins, and a disease allele frequency of 0.0001. Multipoint LOD scores were calculated with the program ALLEGRO.14 All data handling was done with the graphical user interface ALOHOMORA.15 We identified several regions of homozygosity by descent with a maximum parametric LOD score of 2.4 on chromosomes 1, 2, 5, 7, and 16 (Figure S1A, available online). At the same time, DNA samples of both children were subjected to WES. Enrichment, sequencing, read mapping, and variant calling were carried out as previously described.16 The fraction of target regions covered ≥30× for affected individuals FP1-1 and FP1-3 exceeded 82% and 87%, respectively. Filtering and variant prioritization were performed with the Cologne Center for Genomics Varbank database and analysis tool kit (see Web Resources). In particular, we filtered for rare homozygous variants shared by both affected individuals by using the filter parameter settings documented in Table S1. This resulted in a single autosomal variant, namely CKAP2L (RefSeq accession number NM_152515.3) frameshift mutation c.571dupA (p.Ile191Asnfs∗6), caused by an insertion of an additional adenine in exon 4 of CKAP2L. This is consistent with the linkage data given that CKAP2L is in a small linkage interval on chromosome 2 (Figure S1B). Haplotype analysis uncovered a shared homozygous region of 0.93 Mb (Figure S1C). The pathogenic nature of the protein-truncating mutation is further supported by its absence from dbSNP build 135, 1000 Genomes build 20110521, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project Exome Variant Server (EVS) build ESP6500, and our in-house database containing variants from >1,600 exomes. Moreover, segregation analysis of the mutation c.571dupA by Sanger sequencing of DNA samples from all available members of family FP1 confirmed an autosomal-recessive mode of inheritance (Figure S2A).

Figure 1.

Clinical Presentation of Filippi-Syndrome-Affected Individuals with Mutations in CKAP2L

Affected individual FP1-1 and his brother, FP1-3, are shown at the age of 3 years and 5 months. FP1-1 was reported previously as the first child born to an Italian family.8 Note the facial abnormalities and cutaneous syndactyly of the fingers and toes. Although the clinical presentation is very similar, the broad nasal bridge and underdeveloped alae nasi seem to be more pronounced in the younger brother (FP1-3), whereas the cutaneous syndactyly of the fingers is more severe in the older brother (FP1-1). In the bottom row, affected individual FP5-1 is shown at the age of 16 years. He is the first child of double first cousins of Pakistani origin and was reported previously at the age of 5 years and 4 months.7 Earlier in his life, he underwent a surgical intervention to release his cutaneous syndactyly of the third and fourth fingers of both hands. Parents provided written consent for the publication of photographs of their children.

Table 1.

Clinical Findings of Filippi-Syndrome-Affected Individuals with and without CKAP2L Mutations

|

Individual |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP1-1 (Brother of FP1-3) | FP1-3 (Brother of FP1-1) | FP2-1 | FP3-1 | FP4-1 | FP5-1 | FP6-1 | FP7-1 | FP8-1 | FP9-1 (Brother of FP9-3) | FP9-3 (Brother of FP9-1) | |

| Gender | male | male | female | male | male | male | male | male | female | male | male |

| Ancestry | Italian | Italian | Italian | Polish | European | Pakistani | Asian | Turkish | Asian | English | English |

| Consanguinity of parents | no | no | no | no | no | yes (double first cousins) | yes (second cousins) | yes (first cousins) | yes | no | no |

| CKAP2L mutations | c.[571dupA]; [571dupA] | c.[571dupA]; [571dupA] | no | no | no | c.[2T>C];[2T>C] | no | c.[554_555delAA]; [554_555delAA] | c.[157_485del]; [157_485del] | c.[78_79insTT]; [751delA] | not analyzed |

| Measurements | |||||||||||

| Prenatal IUGR | yes | yes | no | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Gestational age at birth | 34 weeks | 38 weeks | 41 weeks | 37 weeks | 39 weeks | 31 weeks | 36 weeks | 39 weeks | 35 weeks | 37 weeks | 38 weeks |

| Length at birth (SD) | −2.0 | NR | −2.0 | +0.9 | NR | NR | −2.0 | −1.3 | NR | NR | NR |

| Weight at birth (SD) | −2.0 | −2.0 | −0.7 | −0.5 | +1.8 | −1.4 | −2.0 | −2.0 | −3.5 | −3.6 | −2.8 |

| OFC at birth (SD) | −3.5 | NR | −1.8 | −2.3 | NR | −2.4 | −1.6 | −2.0 | −4.6 | NR | −2.9 |

| Age at examination | 2 years, 8 months | 3 years, 5 months | 12 years | 3 years, 6 months | 10 years, 6 months | 16 years, 3 months | 3 years | 1 years, 11 months | 10 years, 6 months | 2 years, 10 months | 1 years, 7 months |

| Height at examination (SD) | −5.5 | −1.4 | −3.3 | −0.5 | <−2.0 | −2.8 | −2.0 | −3.3 | −2.0 | −2.6 | −2.4 |

| Weight at examination (SD) | −5.5 | −2.0 | −1.6 | −1.9 | <−2.0 | −0.06 | −2.7 | −2.1 | −2.0 | NR | NR |

| OFC at examination (SD) | −10.0 | −4.0 | −2.0 | −2.8 | −3.8 | −7.0 | −1.4 | −4.1 | −5.5 | −2.9 | −3.0 |

| Neurological Features | |||||||||||

| Intellectual disability | severe | no | moderate | severe | mild to moderate | mild to moderate | moderate | moderate | mild to moderate | mild to moderate | mild to moderate |

| Speech impairment | severe | mild | moderate | severe | moderate | moderate | mild | moderate to severe | mild to moderate | mild to moderate | mild |

| Epileptic seizures | yes | no | yes | no | no | yes | no | no | no | no | no |

| Facial Dysmorphism | |||||||||||

| Broad nasal bridge or telecanthus | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | yes | no | yes | yes |

| Prominent nasal root or bridge | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | no | no | yes | no | no |

| Underdeveloped alae nasi | yes | yes | no | yes | no | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Hands and Feet | |||||||||||

| Syndactyly of fingers | bilateral 3 and 4 (cutaneous) | bilateral 3 and 4 (cutaneous) | bilateral 3–5 (cutaneous), bilateral 3 and 4 (osseous; distal phalanges) | sinistral 3 and 4 (cutaneous) | bilateral 3 and 4 (cutaneous) | bilateral 3 and 4 (cutaneous) | bilateral 3 and 4 (cutaneous) | no | bilateral 3 and 4 (cutaneous) | bilateral 3 and 4 (cutaneous) | no |

| Syndactyly of toes | bilateral 2–4 (cutaneous) | bilateral 2–4 (cutaneous) | bilateral 2 and 3 (cutaneous) | bilateral 4 and 5 (cutaneous), sinistral 1 and 2 (cutaneous) | bilateral 2 and 3 (cutaneous) | sinistral 2–5 (cutaneous), dextral 2–4 (cutaneous) | no | bilateral 2 and 3 (cutaneous) | bilateral 2–4 (cutaneous) | bilateral 2–4 (cutaneous) | bilateral 2 and 3 (cutaneous) |

| Hypoplasia and/or aplasia of phalanges | hypoplasia of fifth toes | hypoplasia of fifth toes | hypoplasias of fingers and toes (mainly middle and distal phalanges) | aplasias: sinistral second finger (middle and distal phalanges), sinistral third toe (total); hypoplasias: dextral toes (multiple phalanges) | no | hypoplasia of fifth toes | no | no | no | no | no |

| Clinodactyly | yes (fifth fingers) | no | yes (fifth fingers) | no | no | yes (fifth fingers) | no | yes (fifth fingers) | no | no | no |

| Ectodermal Abnormalities | |||||||||||

| Hair anomalies | no | double parietal hair whorl | thin | thin | coarse, different colors, abnormal growth pattern | hypertrichosis, abnormal frontal growth pattern | mild hypertrichosis | sparse hair, abnormal growth pattern | no | NR | NR |

| Hypodontia | no | no | yes (agenesis of roots) | no | no | yes | no | no | no | NR | NR |

| Small teeth or abnormally shaped teeth | small teeth | small teeth | no small teeth, abnormal crowns and color | small teeth | no | yes | no | no | abnormally shaped teeth, serrated incisors | NR | NR |

| Other | |||||||||||

| Genital anomalies | cryptorchidism | cryptorchidism | no | cryptorchidism | no | ambiguous genitalia (tiny phallus, hypospadias, flat scrotum) | no | cryptorchidism | NR | cryptorchidism | cryptorchidism |

Abbreviations are as follows: IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; NR, no report available; and OFC, occipital-frontal circumference.

We sequenced CKAP2L in eight additional Filippi-syndrome-affected families, one from Italy (FP2), one from Poland (FP3), one from Turkey (FP7), and five from the UK (FP4–FP6, FP8, and FP9) (Table 1). FP2, FP6, FP7, and FP8 have not previously been described; all others were reported previously.7,9,17 For Sanger sequencing of CKAP2L, primers were designed to encompass all exons and adjacent splice sites. Initially, we sequenced only the DNA of the index person of each family. When a mutation was found, all available family members were tested for this particular variant. We identified five additional mutations in four of the further eight families affected by Filippi syndrome. In the FP5 index individual, a boy born to consanguineous parents from Pakistan,7 we identified in the first codon of CKAP2L homozygous mutation c.2T>C (p.Met1?), which consequentially cannot be used as translational start site (Figure S2B). In FP7, a boy born as the second child of a healthy consanguineous Turkish couple was diagnosed with a Filippi-like syndrome. He showed pre- and postnatal growth reduction, moderate to severe speech impairment, sparse hair, cryptorchidism, and bilateral cutaneous syndactyly of the second and third toes, but interestingly no syndactyly of the fingers (Table 1). Sequencing of his DNA revealed a homozygous 2 bp deletion (c.554_555delAA) causing a frameshift (p.Lys185Argfs∗11) introducing a premature termination codon (PTC). Both parents are heterozygous for this mutation (Figure S2C). In family FP8, a girl born to consanguineous Asian parents, we identified a homozygous 329 bp deletion (c.157_485del) (Figure S2D). The affected individual showed pre- and postnatal growth retardation and speech impairment; she started walking at the age of 3 years and lacked cognitive skills. She had recurrent ear and chest infections requiring repeated treatment with antibiotics, but her hearing and vision were normal. On re-examination at the age of 8 years, she was relatively small and had skin syndactyly of the second, third, and fourth toes and third and fourth fingers. She had a prominent and abnormally shaped nose and serrated incisors. Her clinical data regarding height and weight are summarized in Table 1. Mutation c.157_485del deletes the 5′ end of exon 4, the largest exon of CKAP2L. Similar to the mutation described above for family FP1, the 329 bp deletion creates a frameshift (p.Thr53Tyrfs∗6) resulting in a severely truncated protein (Figure S2D). In family FP9, two affected male siblings were born to nonconsanguineous parents of British ancestry.17 Sequencing of a sample from the older boy identified two different heterozygous frameshift mutations (c.78_79insTT and c.751delA) predicted to result in PTCs in the N-terminal half of the protein (p.Gly27Leufs∗4 and p.Ser251Alafs∗6, respectively). The proband’s mother is heterozygous for one of the two mutations (c.751delA), confirming the compound-heterozygous status of her son (Figure S2E). By identifying six different deleterious mutations (Figure 2A) in five unrelated individuals with Filippi syndrome (Table 1), we provide compelling genetic evidence of a central role for CKAP2L in the etiology of Filippi syndrome. Only one of the six mutations, c.554_555delAA, is described in the NHLBI EVS. It was found in 3 out of 12,507 chromosomes but never in a homozygous state. The detection of carriers of recessive disease alleles in such a large sample size is not unexpected and might characterize c.554_555delAA as a founder mutation. All samples in this study were obtained with written informed consent accompanying the affected individuals’ samples. All clinical investigations were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board of the ethics committee of the University Hospital of Cologne approved the study.

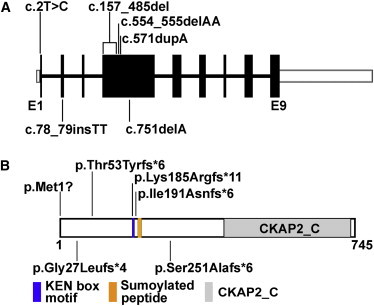

Figure 2.

Position of CKAP2L Mutations Identified in Filippi-Syndrome-Affected Families

(A) Genomic structure of human CKAP2L. The nine exons of CKAP2L are displayed by boxes, which are drawn to scale. The filled boxes represent the open reading frame, and the open boxes represent the UTRs of the transcript. The introns are drawn as connecting lines of arbitrary length. Vertical lines indicate the positions of the mutations. Heterozygous mutations are shown below the schematic, whereas all homozygous mutations are shown above.

(B) Domain organization of CKAP2L as predicted by the NCBI Conserved Domain Database. A peptide of 329 amino acids (residues 415–734) was recognized as cytoskeleton-associated protein 2 C terminus (CKAP2_C). The position of a KEN box motif (Lys-Glu-Asn) is highlighted in blue (residues 185–187). KEN box motifs are known to be a target sequence of APC/C protein CDH1 to initiate proteasomal degradation.18 The position of a nonconsensus sumoylated peptide identified by mass spectrometry is shown in yellow (residues 198–206).19

CKAP2L consists of nine exons and encodes a 745 amino acid polypeptide named cytoskeleton-associated protein 2-like (CKAP2L). It contains the cytoskeleton-associated protein 2 (CKAP2) C terminus domain (CKAP2_C superfamily [pfam15297]), encompassing 319 amino acids at its C terminus, and shares it with CKAP2 (Figure 2B). Recent studies have described the protein as Radmis (radial fiber and mitotic spindle protein) on the basis of its localization to the radial fibers (basal processes) and the bipolar mitotic spindle of dividing neural stem or progenitor cells in murine embryonic and perinatal brains.20 Further, CKAP2L was reported as a component of the human centrosome, where it was located at the spindle pole, the spindle, and the midbody.21 Blomster et al. identified a unique nonconsensus sumoylation site (amino acid positions 198–206 in CKAP2L) in which the lysine at position 198 was sumoylated.19 The level of CKAP2L is tightly regulated during the cell cycle by anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), which recognizes its substrates via a KEN box motif (Lys-Glu-Asn), also present in CKAP2L, and promotes their ordered degradation.18,20 Overexpression of CKAP2L with an altered KEN box in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells induced defective mitotic spindles, which resulted in monopolar and multipolar configurations. In vivo overexpression of wild-type CKAP2L resulted in apparently increased mitosis in the ventricular and subventricular zones (SVZs) of the embryonic mouse brain, whereas excess of CKAP2L with an altered KEN box reduced the proliferation rate of the neuronal progenitor cells and increased their cell-cycle exit. Abnormal differentiation or apoptosis of the neuronal progenitors might lead to the observed reduction of the embryonic SVZ in this model.20 This suggests that tightly regulated levels of CKAP2L are critical for the proper progression of cell division of neural progenitor cells. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that a deregulated level of this protein could directly affect the number of neurons generated during prenatal brain development. Consequently, the outlined findings strongly support CKAP2L as a candidate gene that when mutated might cause a human phenotype with reduced brain size or impaired neuronal function.

Five of the six identified CKAP2L mutations lead to PTCs in the N-terminal part of the protein and thus are likely to cause nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Residual amounts of altered translation products, if formed and stable, would be severely truncated and hence incompatible with normal functioning of the protein. To analyze the effect of absent and/or truncated CKAP2L at the cellular level, we studied Epstein-Barr-virus-infected lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) derived from both affected individuals with the c.571dupA mutation from FP1.22 For immunofluorescence, cells were fixed with prechilled methanol for 10 min at −20°C and blocked with 1× PBS with 5% BSA and 0.45% fish gelatin (PBG) for 15 min. After incubation with primary and respective secondary antibodies, images were obtained by confocal microscopy with a Leica LSM TCS SP5 confocal microscope equipped with a very sensitive hybrid detector (HyD).

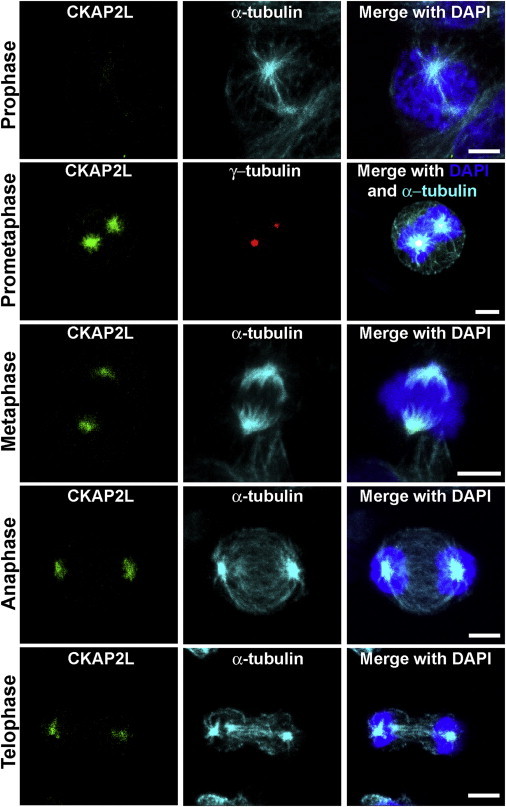

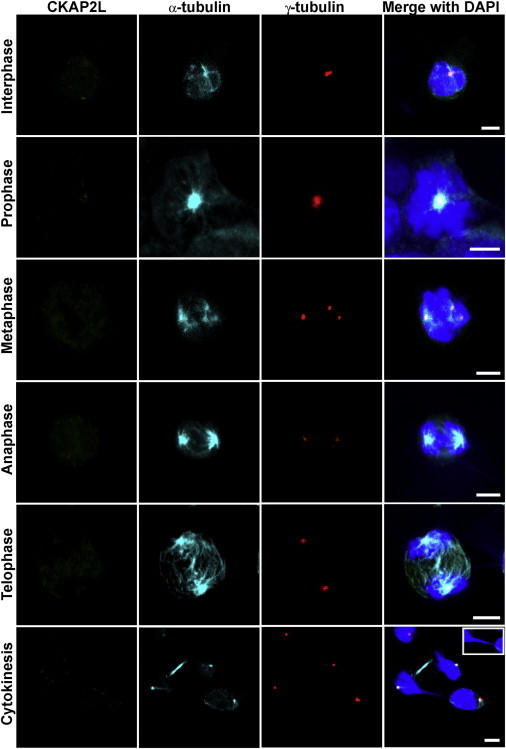

When studying the localization of CKAP2L throughout the cell cycle, we observed very strong CKAP2L staining on microtubules of the spindle pole throughout metaphase to telophase in wild-type cells. We did not detect CKAP2L staining in prophase or interphase (Figure 3). In contrast, CKAP2L was absent at the spindle pole in all dividing cells obtained from both Filippi-syndrome-affected individuals with the c.571dupA mutation. CKAP2L was also not detectable in interphase cells (Figure 4). Immunofluorescence studies were carried out in HaCaT cells. Interphase HaCaT cells did not show CKAP2L staining, but in dividing cells, CKAP2L was present at the spindle poles from prometaphase until telophase (Figure S3). This localization of CKAP2L in wild-type LCLs and HaCaT cells is in keeping with findings in HEK293 and Neuro2a cells.20 The absence of CKAP2L at the spindle pole of the affected individuals’ cells prompted us to analyze further cellular phenotypes associated with the c.571dupA mutation.

Figure 3.

Subcellular Localization of CKAP2L in Wild-Type LCLs

Wild-type LCLs were cultivated in RPMI-1640 (GIBCO, Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin). For analysis of spindle microtubules, the cells were incubated with tubulin-stabilization buffer23 before and after blocking with PBG. Primary antibodies specific to CKAP2L (NBP1-83450, Novus Biologicals, 1:300; green), γ-tubulin (GTU-88, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:300; red), and α-tubulin24 (YL 1/2, 1:20; turquoise) were used. Secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (A21206, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse IgG (A11004, Invitrogen), and Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rat IgG (A21247, Invitrogen) were used as appropriate, and DAPI (D9564, Sigma) was used for DNA detection. CKAP2L was detected at the spindle pole from prometaphase to telophase. Interphase cells did not show any CKAP2L staining. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

Figure 4.

Analysis of CKAP2L Localization, Spindle Morphology, Centrosomes, and DNA in LCLs from Affected Individuals Carrying the c.571dupA Mutation

Confocal-microscopy images of an affected individual’s LCLs, stained for CKAP2L (green), α-tubulin (turquoise), and γ-tubulin (red) and stained with DAPI (blue). Immunoreactivity of CKAP2L was not observed at the spindles or the spindle poles of dividing cells. Defective spindles (metaphase), supernumerary centrosomes (metaphase), and abnormal chromatin bridges (inset) between separating daughter nuclei during cytokinesis accompanied the absence of CKAP2L. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

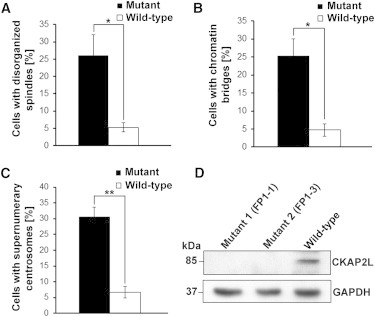

LCLs with c.571dupA (p.Ile191Asnfs∗6) showed severe cellular defects, including disorganized mitotic spindles, a long chromatin bridge between daughter nuclei, and supernumerary centrosomes. LCLs from both affected brothers exhibited disorganized spindle microtubules, which also seemed to be shorter in length. Staining for centrosomal (γ-tubulin) and spindle (α-tubulin) microtubules indicated abnormal multipolar spindles originating from multiple γ-tubulin-positive centrosomes (Figures 4 and S4). About 26% of cells from the affected individual had disorganized mitotic spindles, whereas only 5.33% of wild-type cells had this abnormality (Figure 5A). Given that mitotic spindles ensure proper chromosome segregation during cell division, we investigated the consequences of disorganized mitotic spindles in the LCLs from the affected individuals. Defective spindle microtubules were visible as abnormal connections (“chromatin bridges”) between separating daughter nuclei stained with DAPI in the LCLs from both affected individuals. This phenotype of chromosome lagging was observed during anaphase, telophase, and cytokinesis. Chromatin bridges were mainly observed during cytokinesis (Figure 4). Approximately 25.33% of cells from affected individuals were connected by lagging chromosomes, whereas only 4.66% wild-type cells were (Figure 5B). LCLs from the affected individuals had multiple γ-tubulin-stained centrosomes, and the majority (∼30.66%) of the mitotic cells had three or four centrosomes (which led to multipolar configurations), whereas only 6.66% of wild-type cells had supernumerary centrosomes (Figures 4, 5C, and S4). The level of CKAP2L was analyzed by immunoblotting. A protein of approximately 84 kDa, the predicted molecular weight of CKAP2L, was detected in cell lysates from wild-type LCLs, whereas no protein was observed in cell lysates from LCLs of both individuals with Filippi syndrome (Figure 5D), concordant with the immunofluorescence data.

Figure 5.

Statistical Analysis of Abnormalities of Spindles, Centrosomes, and DNA in LCLs from Affected Individuals

(A) Statistical data of disorganized spindle microtubules observed in wild-type and mutant LCLs from three different experiments (n > 50 cells per experiment). Error bars represent the SEM. p value = 0.0314 (Student’s t test).

(B) Statistical data of chromosome lagging observed between the daughter nuclei during cytokinesis in wild-type and mutant LCLs. A total of 150 cells during mitosis from three different experiments (n = 50 cells per experiment) were analyzed. Error bars represent the SEM. p value = 0.0143 (Student’s t test).

(C) Statistical data of supernumerary centrosomes observed during mitosis in wild-type and mutant LCLs from three different experiments (n > 50 cells per experiment). Error bars represent the SEM. p value = 0.0021 (Student’s t test).

(D) A representative immunoblot with cell lysates from control and mutant LCLs. Wild-type LCLs and affected individuals’ LCLs were harvested by centrifugation and lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer (R0278, Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with a proteinase-inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). After centrifugation, proteins in the supernatant were denatured at 95°C for 5 min in SDS sample buffer. Proteins were separated by 4%–12% SDS-PAGE (EC-890, National Diagnostics) and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane (PROTRANR, Germany). Protein detection was performed with goat polyclonal anti-CKAP2L as the primary antibody (sc-242448, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and GAPDH (G9295, Sigma-Aldrich) as the loading control. Anti-goat IgG peroxidase conjugate (A9452, Sigma) was used as the secondary antibody, and then the blots were developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence system. CKAP2L was not detected in lysates from mutant LCLs, whereas a predicted 84 kDa band was detected in wild-type lysates. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

In addition to microcephaly, syndactyly is a hallmark of Filippi syndrome. To investigate the role of CKAP2L in the etiology of syndactyly, we examined the presence of CKAP2L in mouse embryo tissues with a particular focus on the limb buds. For this, we used immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy as described elsewhere.20 Significant CKAP2L immunoreactivity was observed in the neural progenitor cells throughout the neural tube and in the myotome of an embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5) embryo (Figures 6A and 6B). In contrast, overall CKAP2L staining in the limb buds was weak. However, closer inspection of the developing mouse limb buds revealed that there was a substantial amount of CKAP2L at the spindle poles (arrows) of dividing mesenchymal cells (Figures 6C and 6D). When analyzing embryos at E12.5, the time at which the digits appear, we found that CKAP2L continued to be present in dividing progenitor cells in limb buds, including mesenchymal cells and formative chondrocyte cells of digit cartilage. Intriguingly, strong CKAP2L staining was also seen in the fine processes of myogenic progenitor cells (Figure 6E). These cells are known to be delaminated from the ventrolateral lips of the dermomyotome and to migrate to give rise to limb muscles.25,26 These findings indicate that CKAP2L is expressed at the right places to be involved in the formation of syndactyly, even though the mechanism remains unclear. It might be possible that CKAP2L deficiency impairs apoptosis in the interdigital spaces by virtue of its detrimental effects on mitosis and potential activation of mitotic checkpoints.

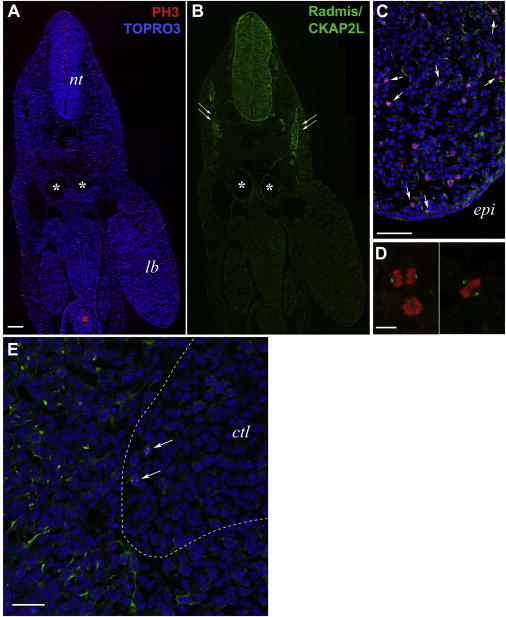

Figure 6.

Detection of CKAP2L in the Murine Embryonic Limb Buds

(A and B) A transverse section of an E10.5 whole mouse embryo coimmunostained for CKAP2L (affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody, 1:10,000; green, B) and the mitosis-specific marker phosphohistone H3 (mouse monoclonal IgG1, clone 6G3, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1,000; red, A). Nuclei were counterstained with TOPRO-3 (Life Technologies; blue). Robust immunoreactivity of CKAP2L was observed in the neural progenitor cells throughout the neural tube and the myotome (double arrows in B). The scale bar represents 100 μm. Abbreviations are as follows: nt, neural tube; and lb, forelimb bud. Asterisks indicate the dorsal aorta and vein.

(C) Higher magnification of the forelimb bud around the apical ectodermal ridge, stained for CKAP2L (green) and phosphohistone H3 (red). The immunoreactivity of CKAP2L was significantly lower in the connective tissues, including the limb buds, than in the neural tube, but close inspection clearly disclosed CKAP2L staining at the mitotic spindles (arrows) of dividing mesenchymal cells, which were loosely distributed in the developing limb bud. Note that the section shown is different from that in (A). The scale bar represents 75 μm. The following abbreviation is used: epi, epithelial ectoderm.

(D) Individual dividing cells in anaphase (left panel) and metaphase (right panel) within the limb bud mesenchyme. CKAP2L localized to the mitotic spindle and spindle poles of mitotic cells. The scale bar represents 50 μm.

(E) CKAP2L staining in an E12.5 forelimb bud. CKAP2L immunoreactivity (green) was detected in the dividing cells (arrows) at the boundary region between the protruding cartilage and the surrounding mesenchyme. These CKAP2L-positive cells might include the mitotic mesenchymal cells and the dividing chondrocyte progenitors. In addition, CKAP2L was detected in the fine processes of myogenic progenitor cells, which delaminated from the ventrolateral lips of the dermomyotome and migrated to give rise to limb muscles. TOPRO-3-stained nuclei are in blue. The scale bar represents 25 μm. The following abbreviation is used: ctl, developing cartilage.

We observed two different types of mutations in our families affected by Filippi syndrome. The majority were PTC-causing frameshift mutations consistent with loss of function. However, the loss of the translational start site, c.2T>C (p.Met1?), needs some more consideration. We could not investigate cells from FP5. Potentially, this mutation causes a redirection of the initiation complex of the translational machinery to another AUG codon further downstream from the original start codon, resulting in the loss of the first 165 amino acids of the primary polypeptide. Intriguingly, an entry in the Ensembl database suggests the existence of a protein starting only at the downstream AUG in exon 4 (ENSP00000438763). It would be interesting to find out whether it really represents a wild-type isoform and, if so, whether it would be functionally redundant to the longer version. In view of the phenotype displayed by individual FP5-1 (Table 1), this redundancy could only be a partial one.

We suggest that all mutations identified in CKAP2L result in a depletion of CKAP2L. At a cellular level, this loss causes defects in spindle organization and leads to multipolarity and disturbed chromosome segregation. Similar results of spindle disorganization, chromosome-segregation defects, and multipolar spindle organization were obtained upon knockdown of CKAP2L in NIH 3T3-13C7 cells.20 Also, CKAP2L depletion by in vivo knockdown, accomplished by in utero electroporation, disrupted the mitotic spindles and caused a catastrophe in chromosome segregation in neural stem or progenitor cells of the developing embryonic mouse brains.20

Together with the data reported recently by Yumoto et al.,20 our findings make CKAP2L, alias Radmis, a very interesting protein in developmental brain research. The presence of a sumoylation site on CKAP2L indicates its diverse role during embryonic development. Mouse CKAP2L is necessary for embryonic and adult neurogenesis to ensure proper brain development. CKAP2L localizes to the bipolar mitotic spindles and radial fibers of the dividing neural progenitors during embryonic and perinatal brain development. In the postnatal brain, CKAP2L localizes in the proliferative region of lateral ventricles and the SVZ that contains glial and neuronal precursors. CKAP2L also localizes to the mitotic spindles and the cellular processes in the dividing cells of the SVZ of the adult brain. Furthermore, electron microscopy visualized CKAP2L on the spindle microtubules and on the walls of paired centrioles in mitotic cells of the SVZ of the adult mouse brain. The presence of CKAP2L in actively dividing neural progenitor cells of prenatal, perinatal, postnatal, and adult brain highlights its role in brain development and might explain why it causes the prenatal and postnatal microcephaly observed in subjects with Filippi syndrome. Further, our findings are consistent with the mitotic-spindle disruption underlying other forms of inherited microcephaly, including mutations in WDR62 (MIM 613583) and ASPM (MIM 605481).27,28 Our observation of supernumerary centrosomes in LCLs of individuals with Filippi syndrome is in line with the data of multiple centrosomes observed in cells carrying mutations in PCNT (MIM 605925) and CEP152 (MIM 613529), which are implicated in the etiology of Seckel syndrome.29,30 The strong presence of CKAP2L in the fine processes of the myogenic progenitor cells of E12.5 mouse embryos also suggests a role in the formation of limb muscle. CKAP2L might play a role in the regulation of apoptosis, a critical and important step in the removal of webbing between the digits during development,31 which is reminiscent of the phenotype of cutaneous syndactyly observed in individuals with Filippi syndrome. The screening of a larger collection of individuals with Filippi syndrome revealed the genetic and clinical heterogeneity of this syndrome. All affected individuals in our study had microcephaly, short stature, characteristic facial features, syndactyly, and intellectual disability. However, intrauterine growth restriction, as well as significant microcephaly evident at birth, seems to be a feature that is characteristic of individuals with biallelic mutations in CKAP2L. All affected individuals with mutations in CKAP2L—but only one (FP6-1) of the four affected individuals without CKAP2L mutations—showed prenatal growth retardation.

In summary, having identified six CKAP2L mutations in five families, we have accumulated strong evidence that CKAP2L is associated with Filippi syndrome. The loss of CKAP2L function affects early development by compromising cell division of neural progenitors. Apparently, it also interferes with apoptosis to visibly affect the tissues between fingers and toes.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all family members for their participation. We are also thankful to Ramona Casper, Nina Dalibor, Elisabeth Kirst, and Yumi Iwasaki for their technical support. P.N. is a founder, CEO, and shareholder of ATLAS Biolabs GmbH. ATLAS Biolabs GmbH is a service provider for genomic analyses. This work was supported by grants from Köln Fortune (M.S.H.) and the Center for Molecular Medicine Cologne (P.N. and A.A.N.).

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

Ensembl Genome Browser, http://www.ensembl.org

NCBI Conserved Domains, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi

NCBI Map Viewer, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mapview/

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server, http://snp.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org

Varbank, https://varbank.ccg.uni-koeln.de

References

- 1.Meinecke P. Short stature, microcephaly, characteristic face, syndactyly and mental retardation: the Filippi syndrome. Report on a second family. Genet. Couns. 1993;4:147–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filippi G. Unusual facial appearance, microcephaly, growth and mental retardation, and syndactyly. A new syndrome? Am. J. Med. Genet. 1985;22:821–824. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320220416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orrico A., Hayek G. An additional case of craniodigital syndrome: variable expression of the Filippi syndrome? Clin. Genet. 1997;52:177–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1997.tb02540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woods C.G., Crouchman M., Huson S.M. Three sibs with phalangeal anomalies, microcephaly, severe mental retardation, and neurological abnormalities. J. Med. Genet. 1992;29:500–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walpole I.R., Parry T., Goldblatt J. Expanding the phenotype of Filippi syndrome: a report of three cases. Clin. Dysmorphol. 1999;8:235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams M.S., Williams J.L., Wargowski D.S., Pauli R.M., Pletcher B.A. Filippi syndrome: report of three additional cases. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999;87:128–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharif S., Donnai D. Filippi syndrome: two cases with ectodermal features, expanding the phenotype. Clin. Dysmorphol. 2004;13:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Battaglia A., Filippi T., Pusceddu S., Williams C.A. Filippi syndrome: further clinical characterization. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2008;146A:1848–1852. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabala M., Stevens S.J., Smigiel R. A case of Filippi syndrome with atypical limb defects in a 3-year-old boy and a review of the literature. Clin. Dysmorphol. 2013;22:146–148. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e3283645a30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandhu M., Malik P., Saha R. Multiple dental and skeletal abnormalities in an individual with filippi syndrome. Case Rep. Dent. 2013;2013:845405. doi: 10.1155/2013/845405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schorderet D.F., Addor M.C., Maeder P., Roulet E., Junier L. Two brothers with atypical syndactylies, cerebellar atrophy and severe mental retardation. Genet. Couns. 2002;13:441–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franceschini P., Licata D., Guala A., Di Cara G., Franceschini D. Filippi syndrome: a specific MCA/MR complex within the spectrum of so called “craniodigital syndromes”. Report of an additional patient with a peculiar mpp and review of the literature. Genet. Couns. 2002;13:343–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazier J., Chernos J., Lowry R.B. A 2q24.3q31.1 microdeletion found in a patient with Filippi-like syndrome phenotype: a case report. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2014;164A:2385–2387. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gudbjartsson D.F., Jonasson K., Frigge M.L., Kong A. Allegro, a new computer program for multipoint linkage analysis. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:12–13. doi: 10.1038/75514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rüschendorf F., Nürnberg P. ALOHOMORA: a tool for linkage analysis using 10K SNP array data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2123–2125. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basmanav F.B., Oprisoreanu A.M., Pasternack S.M., Thiele H., Fritz G., Wenzel J., Größer L., Wehner M., Wolf S., Fagerberg C. Mutations in POGLUT1, encoding protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, cause autosomal-dominant Dowling-Degos disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;94:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fryer A. Filippi syndrome with mild learning difficulties. Clin. Dysmorphol. 1996;5:35–39. doi: 10.1097/00019605-199601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfleger C.M., Kirschner M.W. The KEN box: an APC recognition signal distinct from the D box targeted by Cdh1. Genes Dev. 2000;14:655–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blomster H.A., Imanishi S.Y., Siimes J., Kastu J., Morrice N.A., Eriksson J.E., Sistonen L. In vivo identification of sumoylation sites by a signature tag and cysteine-targeted affinity purification. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:19324–19329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.106955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yumoto T., Nakadate K., Nakamura Y., Sugitani Y., Sugitani-Yoshida R., Ueda S., Sakakibara S. Radmis, a novel mitotic spindle protein that functions in cell division of neural progenitors. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e79895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jakobsen L., Vanselow K., Skogs M., Toyoda Y., Lundberg E., Poser I., Falkenby L.G., Bennetzen M., Westendorf J., Nigg E.A. Novel asymmetrically localizing components of human centrosomes identified by complementary proteomics methods. EMBO J. 2011;30:1520–1535. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCoy J.P., Jr. Handling, storage, and preparation of human blood cells. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 2001;Chapter 5:1. doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy0501s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussain M.S., Baig S.M., Neumann S., Peche V.S., Szczepanski S., Nürnberg G., Tariq M., Jameel M., Khan T.N., Fatima A. CDK6 associates with the centrosome during mitosis and is mutated in a large Pakistani family with primary microcephaly. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:5199–5214. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilmartin J.V., Wright B., Milstein C. Rat monoclonal antitubulin antibodies derived by using a new nonsecreting rat cell line. J. Cell Biol. 1982;93:576–582. doi: 10.1083/jcb.93.3.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buckingham M., Vincent S.D. Distinct and dynamic myogenic populations in the vertebrate embryo. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2009;19:444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bober E., Franz T., Arnold H.H., Gruss P., Tremblay P. Pax-3 is required for the development of limb muscles: a possible role for the migration of dermomyotomal muscle progenitor cells. Development. 1994;120:603–612. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.3.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholas A.K., Khurshid M., Désir J., Carvalho O.P., Cox J.J., Thornton G., Kausar R., Ansar M., Ahmad W., Verloes A. WDR62 is associated with the spindle pole and is mutated in human microcephaly. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:1010–1014. doi: 10.1038/ng.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bond J., Roberts E., Mochida G.H., Hampshire D.J., Scott S., Askham J.M., Springell K., Mahadevan M., Crow Y.J., Markham A.F. ASPM is a major determinant of cerebral cortical size. Nat. Genet. 2002;32:316–320. doi: 10.1038/ng995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalay E., Yigit G., Aslan Y., Brown K.E., Pohl E., Bicknell L.S., Kayserili H., Li Y., Tüysüz B., Nürnberg G. CEP152 is a genome maintenance protein disrupted in Seckel syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:23–26. doi: 10.1038/ng.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffith E., Walker S., Martin C.A., Vagnarelli P., Stiff T., Vernay B., Al Sanna N., Saggar A., Hamel B., Earnshaw W.C. Mutations in pericentrin cause Seckel syndrome with defective ATR-dependent DNA damage signaling. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:232–236. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jordan D., Hindocha S., Dhital M., Saleh M., Khan W. The epidemiology, genetics and future management of syndactyly. Open Orthop. J. 2012;6:14–27. doi: 10.2174/1874325001206010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.