Abstract

Rationale/Objective: In the context of increasing survivorship from critical illness, many studies have documented persistent sequelae among survivors. However, few evidence-based therapies exist for these problems. Support groups have proven efficacy in other populations, but little is known about their use after an intensive care unit (ICU) stay. Therefore, we surveyed critical care practitioners regarding their hospital’s practice regarding discussing post-ICU problems for survivors with patients and their loved ones, communicating with primary care physicians, and providing support groups for current or former patients and families.

Methods: A written survey was administered to 263 representatives of 73 hospitals attending the January 2013 annual meeting of the Michigan Health and Hospitals Association Keystone ICU initiative, a quality improvement collaborative focused on enhancing outcomes across Michigan ICUs.

Results: There were 174 completed surveys, a 66% response rate. Representatives included staff nurses, nursing leadership, physicians, hospital administrators, respiratory therapists, and pharmacists. Sixty-nine percent of respondents identified at least one issue facing ICU survivors after discharge. The concerns most commonly identified by these ICU practitioners were weakness, psychiatric pathologies, cognitive dysfunction, and transitions of care. However, most respondents did not routinely discuss post-ICU problems with patients and families, and only 20% had a mechanism to formally communicate discharge information to primary care providers. Five percent reported having or being in the process of creating a support group for ICU survivors after discharge.

Conclusions: Despite growing awareness of the problems faced by ICU survivors, in this statewide quality improvement collaborative, hospital-based support groups are rarely available, and deficiencies in transitions of care exist. Practice innovations and formal research are needed to provide ways to translate awareness of the problems of survivorship into improved outcomes for patients.

Keywords: critical illness, intensive care unit, recovery, support groups, disability

Intensive care units (ICUs) are organized around acute care and management of patients’ physiologic derangements and end-organ dysfunction. There is evidence of ongoing improvement in short-term mortality, particularly for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome and severe sepsis (1, 2), such that now a significant proportion of patients survive to discharge (3–6). This has been accompanied by evidence that many of these survivors face persistent physical debility, neuropsychiatric pathology, cognitive dysfunction, and decreased quality of life, collectively labeled “post intensive care syndrome” (PICS) (7–11).

There are no proven, widely implemented treatments for PICS, although there are recent promising initial results (8, 12–17). In the absence of specific therapies, many other patient populations routinely use peer support groups, often with evidence of efficacy (18, 19). Because such groups are potentially low-cost interventions that do not require specific licensing and are not typically billed in administrative databases, there is no population-based information about their availability or use.

Therefore, we surveyed critical care practitioners across the state of Michigan participating in the Keystone ICU statewide quality improvement collaborative. We asked about the existence of support groups for patients and their loved ones both during and after discharge from the ICU, along with how ICUs facilitate communication with primary care providers. We also asked critical care providers to list their top three concerns for ICU survivors after discharge. We hypothesized that there would be a lack of focus on the transition back to the outpatient setting and a paucity of support groups in existence, associated with a lack of awareness about PICS problems by providers.

Methods

Design

A written survey was administered to 263 representatives of 73 hospitals attending the January 2013 annual meeting of the Michigan Health & Hospital (MHA) Keystone ICU initiative, a quality improvement collaborative focused on enhancing outcomes across Michigan ICUs. The unit of analysis is the respondent, as participants cannot be reliably linked to their institution. Participants included physicians, nurse managers, staff nurses, clinical nurse specialists, nurse educators, hospital administrators, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, and other professionals, as self-identified by their role in the ICU. The 2013 survey was part of MHA Keystone’s ongoing quality improvement efforts to understand its members’ practices. The survey instrument was internally validated before administration via cognitive interviewing to ensure clarity of survey questions (20). The survey was administered before presentations during the annual meeting on family involvement in the ICU and ICU survivorship; however, such topics were known to be on the agenda and so could have primed clinician awareness of those topics. Analysis of the data for research purposes was approved by the University of Michigan Medical Center Institutional Review Board (HUM00079699).

Measures

In the context of a broader survey about a variety of ICU quality improvement practices, we asked respondents about the existence of support groups in their respective ICUs, communication practices about post–critical illness problems with patients and their primary care providers, and a free text entry about perceptions concerning ICU-related morbidity in survivors after discharge from the hospital. The survey did not define the term “support group.” Respondents were also asked about their professional role and the following unit characteristics: association with academic affiliations, unit size, and closed versus open model. The specific survey questions are available in the online supplement.

Analysis

Free text entries were aggregated into broad conceptual groups by two authors using iterative processes until consensus was achieved. Logistic regression was used to assess bivariable associations between listing any potential problems of ICU survivors and either the reported (1) routine discussion of such problems with patients, or (2) mechanisms to communicate with primary care providers. Because of the low prevalence of these outcomes, no multivariable testing was conducted. SAS 9.1.3 (Cary, NC) was used for data processing and Stata 13 (College Station, TX) for data analysis.

Results

There were 174 completed surveys, a 66% response rate. Characteristics of respondents and the represented ICUs are outlined in Table 1. Staff nurses and nurse managers made up the majority of the cohort, although a wide variety of practitioners were represented. Median ICU bed size was 18, and most ICUs had some form of academic affiliation. Forty-four percent of respondents reported working in either a closed unit or one with mandatory intensivist consultation, and 44% reported an open model.

Table 1.

Respondent and organizational characteristics

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Professional role | Staff nurse/manager: 112 (65) |

| Clinical nurse: 21 (12) | |

| RT/PT/OT/speech: 11(6) | |

| Physician/medical director: 11 (6) | |

| NP/PA: 3 (2) | |

| Other: 14 (8) | |

| Number of units represented by respondents | One unit: 112 (70) |

| More than one unit: 47 (30) | |

| Type of unit | Medical: 78 (45) |

| Surgical: 70 (40) | |

| Cardiac: 54 (31) | |

| Neuro: 34 (20) | |

| Trauma: 27 (16) | |

| Other: 64 (37) | |

| Beds | 1–10: 50 (29) |

| 11–25: 96 (55) | |

| 26–50: 17 (10) | |

| 50–100: 7 (4) | |

| Academic affiliation* | Medical school: 76 (44) |

| Residency: 105 (60) | |

| Fellows: 116 (66) | |

| Other: 13 (7) | |

| Unit model* | Closed: 40 (25) |

| Mandatory intensivist consult: 31 (19) | |

| Open: 72 (44) | |

| Other: 20 (12) |

Definition of abbreviations: ICU = intensive care unit; NP = nurse practitioner; OT = occupational therapy; PA = physician assistant; PT = physical therapy; RT = respiratory therapy.

With respect to unit model and academic affiliation, some crossover was noted as several ICUs fit into multiple categories.

Clinicians were asked in an open-ended format to list the three biggest issues facing ICU survivors after discharge; 69% of respondents identified at least one problem, and more than 50% listed three concerns (Table 2). These free text responses were then qualitatively analyzed and grouped into thematic areas. “Disability and weakness” was the most common response, with 30% of respondents citing this as their primary concern for ICU survivors. Psychiatric pathologies and cognitive dysfunction were the next most cited responses (12 and 11%, respectively). Other common themes were concerns regarding ongoing medical issues, readmissions, follow-up and continuity, and socioeconomic concerns.

Table 2.

Challenges facing intensive care unit survivors from practitioner perspective

| Category | % of Responses |

|---|---|

| Disability and weakness | 30 |

| Psychiatric pathologies | 12 |

| Cognitive dysfunction | 11 |

| Ongoing medical/nutrition issues | 10 |

| Follow-up and continuity | 8 |

| Readmissions | 7 |

| Socioeconomic concerns | 6 |

| Lack of education/understanding | 5 |

| General life change | 4 |

| Compliance | 4 |

| Other | 3 |

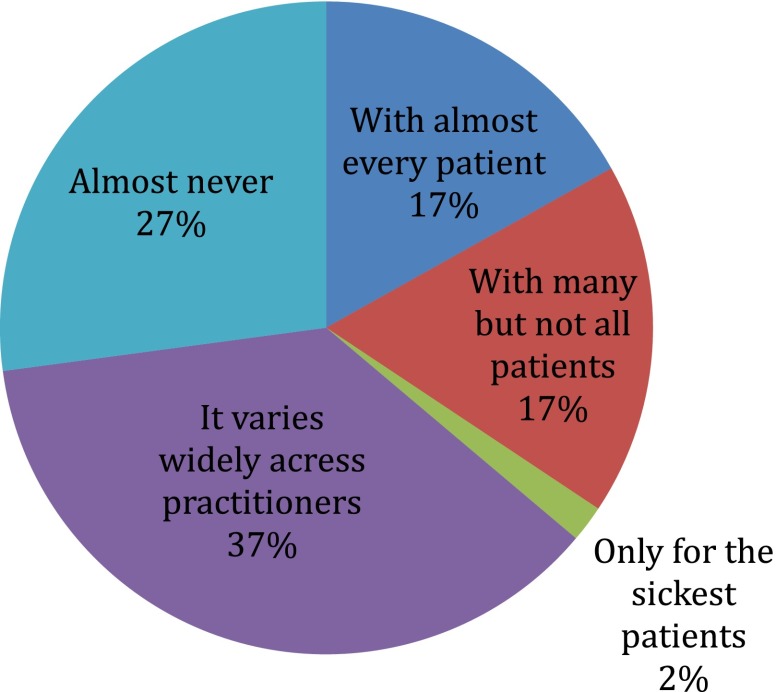

Only 34% of respondents reported having discussions with “almost every” or “many but not all” of their patients and loved ones about post-ICU challenges, whereas more than one-fourth reported that their ICU teams “almost never” communicated these issues to patients (Figure 1). Moreover, only 20% of respondents knew of formal mechanisms within their ICU to ensure communication about a patient’s ICU stay with that patient’s primary care provider. Providers who listed at least one concern were not significantly more likely (odds ratio, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.34–1.34; P = 0.26) to report discussions of these issues with most of their patients, nor were they more likely (odds ratio, 1.19; 95% confidence interval, 0.51–2.77; P = 0.69) to report having a formal mechanism in place to communicate with primary care providers.

Figure 1.

Response breakdown for, “Do medical teams in your ICU have formal discussions with patients or family members regarding challenges and changes to their lives after ICU discharge”? ICU = intensive care unit.

Support groups were reported to be quite rare across the cohort, both while the patient was admitted to the ICU and after discharge with respect to survivors (Table 3). Eighty-four percent of respondents did not have a support group for current patients’ loved ones, and 94% reported that they had no support group in place for patients themselves or for family and friends of ICU survivors after discharge.

Table 3.

Infrequent support groups for intensive care unit survivors

| Existence of support group while patient admitted to ICU |

% |

| Yes, currently in existence | 10 |

| Had group in past, but no group currently | 2 |

| In process of creating group | 4 |

| No | 84 |

| Existence of support group after discharge from ICU | |

| Yes, currently in existence | 2 |

| Had group in past, but no group currently | 1 |

| In process of creating group | 2 |

| No | 95 |

Definition of abbreviation: ICU = intensive care unit.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates a striking absence of support structures for survivors of critical illness and their loved ones in the wide range of hospitals across the state of Michigan. In contrast to our hypothesis, this void is present despite the concurrent finding of active awareness among respondents that critical illness has long-term consequences. Basic communication systems designed to facilitate transitions of care appear to be lacking in represented ICUs. This further highlights that although awareness of PICS has begun to disseminate, there are few mechanisms in place for providers to translate that awareness into direct action for patients.

Furthermore, the present study extends beyond within-ICU communication to identify potential deficits in communication with primary caregivers and in mechanisms to encourage peer support. Regarding the former, deficiencies in transitions of care from in-hospital to out-of-hospital settings are well substantiated by current literature (21, 22). Known challenges include discontinuity between inpatient and outpatient clinicians, complex hospital stays, and discharge summaries, which may be overwhelming or inadequate to outpatient clinicians. As a result of these shortcomings, patients suffer medical errors and adverse events at a significant rate (21, 22). These issues are particularly poignant in the critically ill, given the added complexity of their medical and functional pathologies, which only adds to the physical and psychological burdens felt by patients and their family members (23). Regarding peer support, support groups have known efficacy at ameliorating psychosocial pathologies in multiple other patient populations (18, 19, 24, 25). In fact, a small study in the early 1990s looked at these interventions in critically ill patients and their family members, with marginally improved anxiety levels (26). However, more research and practice innovations are required to develop a portfolio of effective, alternative approaches that can be optimized to specific hospital and patient needs.

Our study has limitations that constrain its interpretation. First, the sample of respondents was drawn from the MHA Keystone ICU annual meeting, which represents a motivated cohort (primarily of nurses) that would not be representative of ICU providers on a national level. However, this likely leads to an overestimation of the frequency with which PICS problems are discussed with patients in a group maximally likely to be aware of formal support group availability. Second, the data for this analysis were obtained from a survey, not from an audit of actual support group existence. Thus, nonresponse bias is a potential limitation, although our response rate compares favorably with the published literature (27). Third, it is possible that this patient population has comorbidities that allow them to access other support structures already in place that were not captured in our data. However, our survey did not specify ICU support groups but rather asked about support groups in general, whether or not they were optimized for critical illness. Fourth, we did not conduct multivariable analyses, particularly for the presence of support groups, because there were so few positive responses that a much larger sample would be necessary for valid statistical inference. Fifth, there were few physicians in the survey sample, and so further research on awareness and practice patterns by physicians is needed. Finally, we did not examine the levels of awareness among staff of the potential impact of critical illness on family members, not just patients—what has been called PICS-family.

The difficulties facing survivors of critical illness and their loved ones are numerous and span a wide range of issues, from physical to cognitive to psychosocial in nature. Our study demonstrates that there are likely substantial opportunities for improvement in the ICU regarding transition back to primary care and in developing support programs. Given the paucity of existing support structures, there is clearly no dominant single model to be tested or compared against in clinical trials or comparative effectiveness research on ways to improve post-ICU care. Instead, practice and research innovation are needed, possibly drawing on what has been learned in related fields, to develop novel approaches for these increasingly surviving patients.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Mark Mikkelsen and Giora Netzer for input in the design of the survey questions and Laetitia Shapiro for input in the preparation of the data.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants K08, HL091249 (T.J.I.) and Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development grant IIR-11-109 (T.J.I.).

The views expressed here are the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent the view of the U.S. Government or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: M.A.M., T.J.I. Data collection: M.A.M., S.R.W., R.C.H. Analysis and interpretation: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: S.G., M.A.M., T.J.I. Revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: S.R.W., R.C.H.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus DC, Wax RS. Epidemiology of sepsis: an update. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S109–S116. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dick A, Liu H, Zwanziger J, Perencevich E, Furuya EY, Larson E, Pogorzelska-Maziarz M, Stone PW. Long-term survival and healthcare utilization outcomes attributable to sepsis and pneumonia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:432. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elixhauser A, Friedman B, Stranges E.Septicemia in U.S. Hospitals, 2009. Statistical Brief #122. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zambon M, Vincent JL. Mortality rates for patients with acute lung injury/ARDS have decreased over time. Chest. 2008;133:1120–1127. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins RO, Suchyta MR, Farrer TJ, Needham D. Improving post-intensive care unit neuropsychiatric outcomes: understanding cognitive effects of physical activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:1220–1228. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1022CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H, Zawistowski C, Bemis-Dougherty A, Berney SC, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, Kahn JM. Population burden of long-term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1070–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwashyna TJ, Netzer G, Langa KM, Cigolle C. Spurious inferences about long-term outcomes: the case of severe sepsis and geriatric conditions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:835–841. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201109-1660OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Needham DM. Mobilizing patients in the intensive care unit: improving neuromuscular weakness and physical function. JAMA. 2008;300:1685–1690. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, Thomason JW, Schweickert WD, Pun BT, Taichman DB, Dunn JG, Pohlman AS, Kinniry PA, et al. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:126–134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O’Connor MF, Hall JB. Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1471–1477. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kress JP. Clinical trials of early mobilization of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:S442–S447. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6f9c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin UJ, Hincapie L, Nimchuk M, Gaughan J, Criner GJ. Impact of whole-body rehabilitation in patients receiving chronic mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2259–2265. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000181730.02238.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, Spears L, Miller M, Franczyk M, Deprizio D, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874–1882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilden JL, Hendryx MS, Clar S, Casia C, Singh SP. Diabetes support groups improve health care of older diabetic patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:147–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Ennis M, Koopmans J, Vincent L, Guther H, Drysdale E, Hundleby M, Chochinov HM, Navarro M, et al. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1719–1726. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sudman S, Bradburn NM, Schwarz N.Thinking about answers: the application of cognitive processes to survey methodologySan Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell CM, Brener SS, Gunraj N, Huo C, Bierman AS, Scales DC, Bajcar J, Zwarenstein M, Urbach DR. Association of ICU or hospital admission with unintentional discontinuation of medications for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2011;306:840–847. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297:831–841. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chui WY, Chan SW. Stress and coping of Hong Kong Chinese family members during a critical illness. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:372–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffiths KM, Calear AL, Banfield M. Systematic review on Internet Support Groups (ISGs) and depression (1): do ISGs reduce depressive symptoms? J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths KM, Mackinnon AJ, Crisp DA, Christensen H, Bennett K, Farrer L. The effectiveness of an online support group for members of the community with depression: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e53244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halm MA. Effects of support groups on anxiety of family members during critical illness. Heart Lung. 1990;19:62–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]