Abstract

The Affordable Care Act was intended to address systematic health inequalities for millions of Americans who lacked health insurance. Expansion of Medicaid was a key component of the legislation, as it was expected to provide coverage to low-income individuals, a population at greater risk for disparities in access to the health care system and in health outcomes. Several studies suggest that expansion of Medicaid can reduce insurance-related disparities, creating optimism surrounding the potential impact of the Affordable Care Act on the health of the poor. However, several impediments to the implementation of Medicaid’s expansion and inadequacies within the Medicaid program itself will lessen its initial impact. In particular, the Supreme Court’s decision to void the Affordable Care Act’s mandate requiring all states to accept the Medicaid expansion allowed half of the states to forego coverage expansion, leaving millions of low-income individuals without insurance. Moreover, relative to many private plans, Medicaid is an imperfect program suffering from lower reimbursement rates, fewer covered services, and incomplete acceptance by preventive and specialty care providers. These constraints will reduce the potential impact of the expansion for patients with respiratory and sleep conditions or critical illness. Despite its imperfections, the more than 10 million low-income individuals who gain insurance as a result of Medicaid expansion will likely have increased access to health care, reduced out-of-pocket health care spending, and ultimately improvements in their overall health.

Keywords: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Medicaid; health policy; insurance, health

Access to affordable and high-quality health care varies widely in the United States. Pervasive inequalities exist across multiple domains, including geographic regions, sex, racial and ethnic groups, and socioeconomic status. An important contributor to such inequalities is variability in health insurance coverage. In the absence of universal health care coverage or insurance, more than 47 million nonelderly Americans were without health insurance in 2012 (1).

Lack of insurance is a particularly important contributor to poor outcomes among patients who have pulmonary disease or those who develop critical illness. For example, relative to the insured, individuals who lack health insurance have a greater incidence of lung cancer, are often diagnosed at a later stage of disease, and experience worse survival (2). Similarly, among those with asthma, a lack of health insurance has been associated with markers of poor outpatient care, such as a lack of inhaled corticosteroid use and a decreased likelihood of admission to the hospital from the emergency department (3). Uninsured critically ill patients are less likely to receive potentially life-saving critical care procedures (4, 5), receive less postacute care during critical illness recovery (6), and have increased mortality compared with those with insurance (7–9).

To address the health inequalities that stem from a lack of insurance, President Obama signed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act into law in March 2010, the most significant and comprehensive health care reform since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. The Affordable Care Act created an individual mandate that requires most U.S. citizens and legal residents to have health insurance or face a tax penalty. To facilitate the mandated coverage of individuals who were previously uninsured, the legislation also provided several new policies expanding private insurance; however, the largest proportion of uninsured Americans is expected to gain health insurance coverage through Medicaid expansion. Several studies highlight the potential benefits of Medicaid expansion on health care access, health outcomes, and financial peace of mind for the poor. Yet, Medicaid is an imperfect program that may not reach the full potential of private plans. In this perspective, we describe the potential impact of Medicaid expansion on health care access; quality; and outcomes for patients with pulmonary, sleep, and critical care disorders, and discuss the inequities that will remain for individuals insured through Medicaid.

Medicaid Expansion: Promise versus Reality

Created by the Social Security Amendments of 1965, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program were designed as the nation’s health care safety net. Before the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program provided insurance coverage to nearly 18% of nonelderly Americans (10), including many low-income individuals, such as children, their parents, pregnant women, and those with disabilities. Although federal law required states to provide coverage for school-age children up to 100% of the poverty level, this was only mandated for those with incomes below an individual state’s 1996 welfare eligibility levels. Ultimately, two-thirds of states limited parental eligibility to less than 100% of the current poverty level (11), with individual states such as Alabama limiting the parental eligibility to as low as 23% of the federal poverty level in 2013 (10). Individuals without children have typically been ineligible for Medicaid coverage regardless of income, with only 9 states providing non-Medicaid, state-funded benefits to childless adults in 2009 (12).

The Affordable Care Act was designed to significantly expand Medicaid eligibility, particularly for adults. Under the proposed law, states would have been required to provide Medicaid for both parents and those without dependent children with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level (currently approximately $27,000 for a family of three). To offset the financial burden of covering more individuals, the Affordable Care Act stipulates that the federal government will cover the full cost of Medicaid expansion for each state, with a stepwise decrease in federal government cost sharing down to 90% in 2020. Anticipating that hospitals will be responsible for less uncompensated care as patients gain coverage, the Affordable Care Act also will concomitantly reduce the Disproportionate Share Hospital payments, federal payments that help hospitals offset the cost of providing care to low-income individuals. Initially slated to begin in 2014, but delayed until 2016 by the bipartisan budget act in December 2013, these reductions will start at 1.2 billion dollars annually for fiscal year 2016, increasing yearly to 4 billion dollars in 2020. The annual reduction each state will receive will vary and has yet to be determined (13).

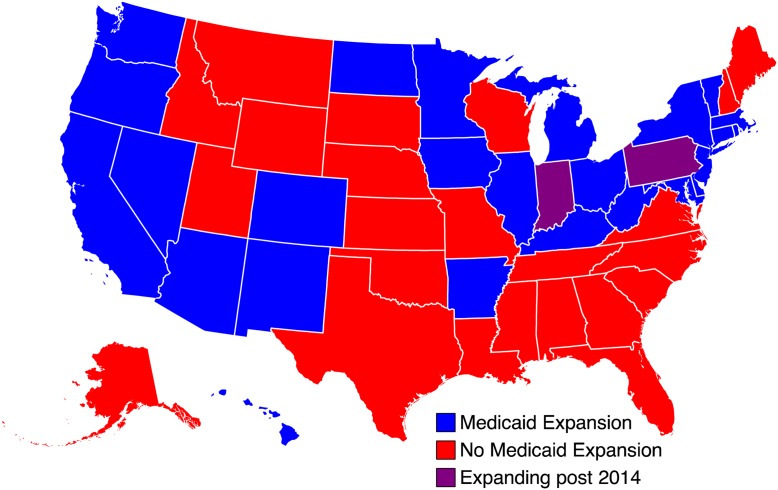

Under these new eligibility requirements, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that 17 million nonelderly adults would have gained coverage under Medicaid expansion (14). However, in June 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court found that states cannot be mandated to participate in the proposed Medicaid expansion, giving states the option either to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act or to keep their preexisting level of Medicaid benefits without risking loss of federal funding. As of February 9, 2014, 25 states indicated they would not participate in Medicaid expansion at this time (Figure 1) (15, 16). While the Congressional Budget Office anticipates that most states will eventually participate in Medicaid expansion despite initially declining, the revised enrollment estimates project 4 million fewer new enrollees by 2023, or approximately 25% fewer than initially anticipated under mandated Medicaid expansion (14).

Figure 1.

Medicaid expansion by state.

Consequences of Nonparticipation in State Medicaid Expansion

In states that fail to expand access to Medicaid there is a significant probability that millions of lower-income parents and childless adults will remain without health insurance. Paradoxically, many states choosing not to expand Medicaid coverage potentially have the most to gain as they have a relatively greater proportion of residents without health insurance (Table 1). Many uninsured individuals in these states are low-income, do not have access to employee-based coverage, and will remain ineligible for their state’s current Medicaid coverage after reform. Furthermore, their incomes will be too low (i.e., less than 100% of the federal poverty level) to qualify for health insurance premium credits, which would otherwise offset the expense of purchasing insurance coverage through state insurance exchanges. These individuals are left in a “coverage gap” where they are ineligible for both subsidies to facilitate the purchase of private insurance because their income is too low and ineligible for Medicaid because their income is too high. Although subsidies are not required to purchase insurance through the exchange, the cost of purchasing coverage without premium credits will likely remain prohibitive for those in this coverage gap, as the average premium for a 40-year-old adult is $224 per month for the most basic bronze plan (15).

Table 1.

2014 Medicaid expansion among states with highest and lowest rates of nonelderly uninsured

| State | Percentage Nonelderly Uninsured, 2011–2012* | Expanding Medicaid in 2014 | Percentage below 100% Poverty Level† | Life Expectancy at Birth (State’s Rank) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 17.9 | — | 15.0 | — |

| Texas | 26.8 | No | 17.4 | 32 |

| Nevada | 26.5 | Yes | 15.5 | 38 |

| Florida | 24.7 | No | 14.9 | 23 |

| New Mexico | 24.3 | Yes | 22.2 | 34 |

| Louisiana | 22.4 | No | 21.1 | 50 |

| Connecticut | 9.5 | Yes | 10.1 | 5 |

| Vermont | 9.3 | Yes | 11.6 | 8 |

| Hawaii | 9.1 | Yes | 12.1 | 1 |

| District of Columbia | 9.1 | Yes | 19.9 | 45 |

| Massachusetts | 4.4 | Yes | 10.6 | 6 |

Failure to expand access to Medicaid in these states may also have important consequences for insured patients who access care through the safety net. Those who fall into the coverage gap will likely continue to face barriers to nonemergency care with associated worse health outcomes and potentially serious financial hardships when they do seek care. Failure to expand Medicaid will likely have adverse effects on the health of indigent women: more than half of states that elected not to expand Medicaid have higher than average rates of women who lack health insurance (17). Safety net health service providers and hospitals in these states—systems that typically serve minority populations and the poor—are also likely to suffer from limitations in resources and reduced Disproportionate Share Hospital payments as they continue to shoulder the burden of uncompensated care costs. For example, safety net hospitals tend to have slower gains in the quality of care provided to patients with pneumonia and tend to be poorer performers relative to non–safety net hospitals (18, 19). Importantly, these deficiencies in care quality spill over to impact all of those served by safety net health systems, not just those who lack insurance. Without the infusion of resources from newly covered Medicaid patients, these disparities in quality will likely persist.

Will the Affordable Care Act’s Expansion of Medicaid Remedy Insurance-based Disparities?

One can gain insight into the expected impact of Medicaid expansion from prior observational and quasi-experimental analyses of health insurance expansion in the United States (20–22). Massachusetts initiated health insurance reform in 2006 in a comprehensive program that includes many provisions incorporated in the Affordable Care Act, including the majority of new insurance beneficiaries obtaining insurance through Medicaid expansion. In Massachusetts, health insurance reform was associated with an increase in primary care use (23), a decrease in use of the emergency department for low-severity conditions (24) and nonurgent conditions (25), and a concomitant decrease in overall hospitalizations for preventable conditions (23, 26). Massachusetts health insurance reform was also associated with an increase in outpatient surgical referrals among lower income racial/ethnic minorities in the postreform period (27). There was also a significant reduction in the number of critically ill patients without health insurance in Massachusetts after health insurance reform. Despite this reduction, intensive care unit use as measured by intensive care unit admissions per capita or intensive care unit admissions per hospitalization was unchanged, and there were no changes in mortality or use of post–acute care facilities among patients admitted to the intensive care unit (28).

Several states had expanded Medicaid benefits before the advent of the Affordable Care Act. Arizona, Maine, and New York significantly expanded Medicaid access to poor parents and childless adults between 2000 and 2005. Compared with neighboring states that did not undertake expansion, these states experienced a significant increase in Medicaid coverage and a concomitant decrease in the numbers of uninsured. States that expanded Medicaid also experienced a significant reduction in mortality compared with states that did not expand. Finally, Medicaid expansion was associated with increased rates of self-reported health status of “excellent” or “very good” (29).

Perhaps the most definitive study examining the impact of gaining Medicaid insurance was the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment. In 2008, Oregon offered Medicaid coverage to approximately 30,000 uninsured poor adults from a recruited waiting list of almost 90,000. Individuals selected for Medicaid coverage were chosen via lottery, effectively randomizing those on the wait list to either coverage or no coverage, setting up the largest randomized controlled trial of insurance expansion in history. Medicaid coverage was responsible for significant increases in preventive health care, including mammograms, cholesterol screening, and Pap smears, improvements in self-reported general health, quality of life, and reductions in depression. Although gaining Medicaid did result in greater use of diabetic medications for those with diabetes, it did not improve hemoglobin A1C levels. Other preventive health outcomes, such as blood pressure and cholesterol levels, were also unchanged, although residents of Oregon had significant lower rates of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia compared with national averages. The impact of gaining insurance on the care for patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease has not yet been reported. Access to, and use of primary care, prescription drugs, and preventive services were significantly improved among Medicaid beneficiaries. Medicaid also dramatically reduced Medical debt and the need to borrow money to pay for medical bills (30). In the year after health insurance acquisition, hospital admissions increased by 30% in one year for those who gained insurance (31). Similarly, those who acquired Medicaid insurance had a 40% relative increase in emergency department visits compared with control subjects (32).

Overall, these studies of prior state-level expansions suggest that individuals who gain Medicaid coverage experience greater access to the health system in general, greater access to preventive care, and discrete improvements in health outcomes while experiencing reduced financial strain from medical bills. Despite increased access to health services in Massachusetts, health insurance expansion did not significantly increase intensive care use, suggesting that at least in the short term, there may be similarly no increase in critical care use after national health care expansion. It is reasonable to anticipate that the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion provision will begin to address some of the insurance-related inequities in care in the United States.

Medicaid and Health Outcomes: Necessary but Not Sufficient

Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act represents an important and historic step toward mitigating health insurance–related disparities, likely improving access, reducing patient financial strain, and possibly improving health status. However, it is important to recognize that even if universally adopted at the state level, the availability of insurance does not guarantee that individuals will ultimately receive high-quality care. Even when insurance is available, patients must enroll and overcome deficiencies in access to covered services, clinicians and institutions, and deficiencies in access to high-quality primary care and specialty services (33). In this regard, Medicaid is typically underfunded compared with private insurance, leading to deficiencies that may curb its ability to eliminate insurance-related disparities.

Deficiencies in Essential Health Benefits Package

The Affordable Care Act includes an essential health benefits package, which establishes a comprehensive set of the minimum necessary services that a Medicaid expansion plan must provide (Table 2). The Affordable Care Act mandates coverage in the 10 essential health benefits categories. Coverage is thus assured for the majority of services commonly performed and billed by pulmonary and critical care providers. However, states ultimately have discretion to determine how many services within each of the 10 categories their Medicaid plans will cover, which may lead to significant state-to-state variability in benefits. Furthermore, newly eligible groups may not receive benefits as comprehensive as traditional Medicaid, provided they cover at least 1 service within each of the 10 categories (34).

Table 2.

Services required for an insurance plan to be considered compliant with the essential health benefits package

| The Essential Health Benefits Package | |

|---|---|

| Ambulatory patient services (e.g., initial and subsequent visits, procedures, pulmonary function studies) | Prescription drugs |

| Emergency services | Rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices (e.g., physical therapy) |

| Hospitalization (e.g., inpatient initial and subsequent visit, consultation, procedures, critical care, transplantation) | Laboratory services |

| Maternity and newborn care | Preventive and wellness services and chronic disease treatment (e.g., vaccination, smoking cessation) |

| Mental health and substance use services, including behavioral health treatment | Pediatric services including oral and vision care |

Variability among individual states’ interpretation and implementation of the essential health benefits when expanding Medicaid may have important consequences for patients with pulmonary disease, critical illness, or sleep disorders. The essential health benefits requirement for prescription drug coverage does not guarantee access to the range of necessary medications that could best meet a patient’s needs, but instead stipulates that patients must have access to a specific number of medications. Lung transplant recipients, for example, typically require at least three immunosuppressant medications, which are in the same class and category. Under the current essential health benefits health plans are only required to cover two drugs per class, potentially limiting access to these life-saving medications (35). The current prescription drug rule could also significantly impact providers’ ability to treat single- and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Combination therapies (e.g., fluticasone/salmeterol inhaler) are also not recognized under the current proposal, which may threaten the health of patients with cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, asthma, and pulmonary hypertension (35, 36). Tobacco cessation aids, which are consistently demonstrated to be more effective in combination (37), will also potentially be limited to one medication per class or category, thus limiting important therapeutic options for this vulnerable population (35, 36).

Beyond the limitations of the prescription drug benefit, the essential health benefits also fail to adequately address other services essential to the care of patients with pulmonary, critical care, and sleep disorders. In particular, the essential health benefits do not describe whether patients will have access to durable medical equipment such as ventilators, nebulizers, and continuous positive airway pressure machines, leaving open the possibility that patients will have to pay for these life-saving devices out of pocket (35). Last, diagnostic testing, evaluation, and treatment of sleep disorders, and patient–physician counseling regarding end-of-life and palliative care, are not included in minimum benefit standards under the current essential health benefits proposal such as that provided to current Medicaid or Medicare beneficiaries (35).

Cost Sharing among Medicaid Beneficiaries and Access to Necessary Services

In addition to the significant variability in Medicaid benefit benchmarks, the Affordable Care Act allows states to set cost-sharing limits for certain services. By requiring individuals to share in the costs of accessing the health care system, cost sharing is an effective means through which insurance plans can reduce unnecessary health care use. Several studies have demonstrated that for the poorest and sickest patients, cost-sharing plans worsen outcomes relative to free plans because cost sharing also decreases the likelihood that individuals will seek necessary care. Among the poor, patients with cost-sharing plans are also less likely to fill prescriptions for essential medications, and as a result experience increases in emergency department visits, and a greater likelihood of adverse health events (38).

States can set their own cost-sharing limits for nonemergency use of the emergency department for individuals with incomes greater than 150% of the federal poverty level. In reality, in many areas of the country, emergency departments are the only health care facilities continuously available for the treatment of urgent respiratory illness such as asthma (39). Cost-sharing in this context may be a significant deterrent to seeking timely care and could lead to worse outcomes for these patients. Patients who gain Medicaid insurance will also be required to share in the costs of preventive services, whereas individuals who are newly insured under a private-market insurance plan can receive preventive services and immunizations recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force without cost-sharing (36, 39). Cost-sharing is also proposed for tobacco cessation counseling and medications for all nonpregnant Medicaid recipients. Together, these cost-sharing policies have the potential to significantly impact the health of Medicaid beneficiaries (36).

Medicaid and Access to Specialty Care

Medicaid patients with pulmonary or sleep disorders may experience inequalities that result from individual providers and groups choosing not to accept patients with Medicaid insurance in their practices (40). Medicaid typically reimburses physicians at a lower rate than Medicare or private insurance, yet Medicaid patients often present with equally complicated medical illness in the context of social situations that complicate medical treatment. Recognizing this financial disincentive for providers to accept new Medicaid patients, the Affordable Care Act requires states to pay physicians Medicaid fees that are at least equal to Medicare’s for inpatient and outpatient evaluation and management services, including E/M codes (99,201 through 99,449). This group of E/M codes includes many of the services commonly performed and billed by pulmonary and critical care providers. However, there is no similar parity in physician fees for other subspecialty services, including but not limited to injection of omalizumab, procedures, or interpretation of pulmonary function tests and sleep studies. As such, some of the financial disincentives for pulmonary, allergy, sleep, and critical care providers to deliver care for Medicaid patients will persist. Even when providers do accept Medicaid insurance, access and outcome disparities will remain. At least one study demonstrated that children with Medicaid faced significant delays in accessing specialty care even when specialists accepted Medicaid, compared with those with private insurance (41). Similarly, although outcomes for those with Medicaid are generally better than for the uninsured, Medicaid beneficiaries continue to experience delays in diagnoses (lung cancer [2]) and increased mortality (cancer [2], critical care [28]) when compared with those with private health insurance.

Faced with decreasing reimbursements, specialty service providers will need to adopt innovative and creative approaches to sustain economic viability and ensure high-quality care. Potential options to support Medicaid expansion while mitigating expenses include distributing Medicaid patients proportionately across providers in the area, expanding the role for mid-level providers, and group clinic management for patients with chronic diseases.

Medicaid’s Reach Will Not Be Universal under the Affordable Care Act

Even if Medicaid expansion were fully implemented across all states, important segments of the population would remain marginalized under the current program. Undocumented immigrants, and lawfully present immigrants who have been in the United States for fewer than 5 years, remain ineligible for Medicaid. Access to coverage for women’s health established by the Affordable Care Act, particularly contraceptives, is mired in complex legal challenges (17). For lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered individuals the Affordable Care Act outlines provisions of nondiscrimination, and federal regulations stipulate that insurance marketplaces will recognize same-sex marriages and that tax credits will be based on couples’ income. The federal government has encouraged states to also recognize same-sex marriage for the determination of Medicaid eligibility; however, this decision ultimately lies with each state (42). These important inequalities in access to and delivery of health care represent complex policy issues that require a more comprehensive legislative response. Importantly, as Medicaid expands, and states bear greater responsibility for the costs of expansion, alternative safety net resources for those in coverage gaps may be further limited.

Conclusions

Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act is likely to provide an important step forward in addressing gaps in safety net coverage in the United States for low-income individuals, thereby providing an important remedy for health inequalities in the United States. Evidence from prior insurance expansions suggests that the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion will improve self-reported health, increase the use of preventive and primary care services, and decrease financial strain due to medical illness. Early reports confirm that 3 million new Medicaid enrollees of the 6.3 million eligible individuals nationally have enrolled through February 2014 from states that have adopted Medicaid expansion; fivefold higher compared with states that are not expanding Medicaid (43). Although Medicaid expansion is a promising first step in improving insurance-related health care disparities, studies in our specialty have shown consistent disparities in health outcomes for patients with Medicaid compared with private insurance (2, 7). Further, without national adoption of Medicaid expansion, and wide variation in income eligibility thresholds across states electing to expand, significant coverage gaps will exist for millions of Americans, potentially exacerbating health care disparities in these areas. Residents of states that accept the Medicaid expansion will still face challenges in accessing needed services due to important deficiencies in essential health benefits, financial strain resulting from cost-sharing provisions targeted at Medicaid beneficiaries, and decreased access to specialists relative to those insured with private insurance.

In addition to the impact for patients, Medicaid expansion will enhance the availability of providers and health systems to identify and address health disparities (44, 45). Among all the known contributors to health, access to health care plays a minor role. Until the United States definitively addresses inequities in those social and economic domains that are key to health, such as behaviors, education, income, and environment, inequalities in health will persist. In the interim, the immediate imperative for pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine practitioners, researchers, and their professional societies is to constructively support health insurance expansion under the Affordable Care Act. Additionally advocating for improving existing policies to expand patient access to pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine services while reducing barriers for providers, can secure the goal of facilitating access to timely outpatient and acute care services for all of our patients while improving health outcomes on both the individual and societal levels.

Footnotes

Supported by Mentored Clinical Scientist Research Career Development Award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08HS020672) (C.R.C.).

Author disclosures are available with the text of this perspective at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the UninsuredThe uninsured: a primer. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2013. [accessed 2014 Apr 18]Available from: http://kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-on-the-eve-of-coverage-expansions/

- 2.Slatore CG, Au DH, Gould MK American Thoracic Society Disparities in Healthcare Group. An official American Thoracic Society systematic review: insurance status and disparities in lung cancer practices and outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1195–1205. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-038ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferris TG, Blumenthal D, Woodruff PG, Clark S, Camargo CA MARC Investigators. Insurance and quality of care for adults with acute asthma. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:905–913. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.20230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas JS, Goldman L. Acutely injured patients with trauma in Massachusetts: differences in care and mortality, by insurance status. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1605–1608. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapoport J, Teres D, Steingrub J, Higgins T, McGee W, Lemeshow S. Patient characteristics and ICU organizational factors that influence frequency of pulmonary artery catheterization. JAMA. 2000;283:2559–2567. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lane-Fall MB, Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Benson NM, Kahn JM. Insurance and racial differences in long-term acute care utilization after critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1143–1149. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318237706b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyon SM, Benson NM, Cooke CR, Iwashyna TJ, Ratcliffe SJ, Kahn JM. The effect of insurance status on mortality and procedural use in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:809–815. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0089OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danis M, Linde-Zwirble WT, Astor A, Lidicker JR, Angus DC. How does lack of insurance affect use of intensive care? A population-based study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2043–2048. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227657.75270.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyle JJ., Jr Health insurance, treatment and outcomes: using auto accidents as health shocks. Rev Econ Stat. 2005;87:256–270. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the UninsuredMedicaid: a primer. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2013. [accessed 2014 Apr 18]Available from: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2010/0607334–05.pdf

- 11.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Medicaid eligibility for adults as of January 1, 2014. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2013 [accessed 2014 Apr 18]. Available from: http://kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaid-eligibility-for-adults-as-of-january-1–2014/

- 12.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Expanding Medicaid to low income childless adults under health reform: key lessons from state experiences. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2013. Available from: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8087.pdf Accessed April 5, 2014

- 13.Hatch-Vallier L.Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital programs. Ann Arbor, MI: Center for Healthcare Research and Transformation; 2014. [accessed 2014 Apr 18]Available from: http://www.chrt.org/assests/policy-papers/CHRT-Medicaid-and-Medicare-Disporportionate-Share-Hospital-Programs.pdf

- 14.Crowley RA, Golden W. Health policy basics: Medicaid expansion. Ann Intern Med. 2013;160:423–425. doi: 10.7326/M13-2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. The coverage gap: uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2013. Available from: http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/ Accessed April 4, 2014

- 16.Advisory Board Company. Where the states stand on Medicaid expansion. Washington, DC: Advisory Board Company;2014. Available from: http://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/resources/primers/medicaidmap Accessed April 4, 2014

- 17.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Health reform: implications for women’s access to coverage and care. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2013. Available from: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/7987–03-health-reform-implications-for-women_s-access-to-coverage-and-care.pdf Accessed April 5, 2014

- 18.Werner RM, Goldman LE, Dudley RA. Comparison of change in quality of care between safety-net and non–safety-net hospitals. JAMA. 2008;299:2180–2187. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.18.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayr FB, Yende S, D’Angelo G, Barnato AE, Kellum JA, Weissfeld L, Yealy DM, Reade MC, Milbrandt EB, Angus DC. Do hospitals provide lower quality of care to black patients for pneumonia? Crit Care Med. 2010;38:759–765. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c8fd58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Medicare spending for previously uninsured adults. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:757–766. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Use of health services by previously uninsured Medicare beneficiaries. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:143–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa067712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Health of previously uninsured adults after acquiring Medicare coverage. JAMA. 2007;298:2886–2894. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.24.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long SK, Masi PB. Access and affordability: an update on health reform in Massachusetts, fall 2008. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w578–w587. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smulowitz PB, Lipton R, Wharam JF, Adelman L, Weiner SG, Burke L, Baugh CW, Schuur JD, Liu SW, Sayah A, et al. Emergency department utilization after the implementation of Massachusetts health reform Ann Emerg Med 201158225–234.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller S. The effect of insurance on emergency room visits: an analysis of the 2006 Massachusetts health reform. J Public Econ. 2012;96:893–908. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolstad J, Kowalski A. The impact of health care reform on hospital and preventative care: evidence from Massachusetts. J Public Econ. 2012;96:909–929. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanchate AD, Lasser KE, Kapoor A, Rosen J, McCormick D, D’Amore MM, Kressin NR. Massachusetts reform and disparities in inpatient care utilization. Med Care. 2012;50:569–577. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824e319f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyon SM, Wunsch H, Asch DA, Carr BG, Kahn JM, Cooke CR. Use of intensive care services and associated hospital mortality after Massachusetts healthcare reform. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:763–770. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1025–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baicker K, Finkelstein A. The effects of Medicaid coverage—learning from the Oregon experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:683–685. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1108222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, Bernstein M, Gruber J, Newhouse JP, Allen H, Baicker K. The Oregon health insurance experiment: evidence from the first year. Q J Econ. 127:1057–1106. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjs020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taubman SL, Allen HL, Wright BJ, Baicker K, Finkelstein AN. Medicaid increases emergency-department use: evidence from Oregon’s health insurance experiment. Science. 2014;343:263–268. doi: 10.1126/science.1246183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenberg JMP, Power EJ. Transforming insurance coverage into quality health care: voltage drops from potential to delivered quality. JAMA. 2000;284:2100–2107. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broaddus M.Childless adults who become eligible for Medicaid in 2014 should receive standard benefits package. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2010. [accessed 2014 Apr 18]Available from: www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=322925

- 35.Kraft M.re: CMS-9980-P. In: Kathleen Sebelius, Department of Health and Human Services. American Thoracic Society Comments on the Department of Health and Human Service’s essential health benefits for health insurance exchanges. American Thoracic Society; 2012. [accessed 2014 Apr 25]. Available from: http://thoracic.org/advocacy/comments-testimony/index.php [Google Scholar]

- 36.Billings PG. re: CMS-9980-P [a letter from Paul G. Billings, Senior Vice President of the American Lung Association to Kathleen Sebelius, Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services], February 21, 2013. Available from: http://www.lung.org/get-involved/advocate/advocacy-documents/medicaid-ehb-cost-sharing-comments-2-21-13.pdf Accessed April 5, 2014

- 37.Zwar NA, Mendelsohn CP, Richmond RL. Supporting smoking cessation. BMJ. 2014;348:f7535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamblyn R, Laprise R, Hanley JA, Abrahamowicz M, Scott S, Mayo N, Hurley J, Grad R, Latimer E, Perreault R, et al. Adverse events associated with prescription drug cost-sharing among poor and elderly persons. JAMA. 2001;285:421–429. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kraft M.re: CMS-2334-P. Marilyn Tavenner, Acting Administrator, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; American Thoracic Society comments on the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services proposal for Medicaid and health insurance exchange eligibility. American Thoracic Society; 2013. [accessed 2014 Apr 25]. Available from: http://thoracic.org/advocacy/comments-testimony/index.php [Google Scholar]

- 40.Decker SL. In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1673–1679. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Auditing access to specialty care for children with public insurance. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2324–2333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1013285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ranji U, Beamesderfer A, Kates J, Salganicoff A.Health and access to care and coverage for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals in the U.S. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2013. Available from: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/8539-health-and-access-to-careand-coveragefor-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-individuals-in-the-u-s.pdf

- 43.Medicaid & CHIP.February 2014 Monthly Applications, Eligibility Determinations, and Enrollment Report [accessed 2014 Apr 21]Available from: http://www.medicaid.gov/AffordableCareAct/Medicaid-Moving-Forward-2014/Downloads/February-2014-Enrollment-Report.pdf

- 44.McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:78–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Booske BCAJ, Kindig DA, Park H, Remington PL.Different perspectives for assigning weights to determinants of health. 2010. Available from: http://uwphi.pophealth.wisc.edu/publications/other/different-perspectives-for-assigning-weights-to-determinants-of-health.pdf Accessed April 5, 2014

- 46.U.S. Census. POV46: poverty status by state 2011. Current Population Survey 2011. Available from: http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/cpstables/032012/pov/POV46_001_100125.htm Accessed April 5, 2014