Abstract

Lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) are a persistent and pervasive public health problem worldwide. Pneumonia and other LRTIs will be among the leading causes of death in adults, and pneumonia is the single largest cause of death in children. LRTIs are also an important cause of acute lung injury and acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Because innate immunity is the first line of defense against pathogens, understanding the role of innate immunity in the pulmonary system is of paramount importance. Pattern recognition molecules (PRMs) that recognize microbial-associated molecular patterns are an integral component of the innate immune system and are located in both cell membranes and cytosol. Toll-like receptors and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain–like receptors (NLRs) are the major sensors at the forefront of pathogen recognition. Although Toll-like receptors have been extensively studied in host immunity, NLRs have diverse and important roles in immune and inflammatory responses, ranging from antimicrobial properties to adaptive immune responses. The lung contains NLR-expressing immune cells such as leukocytes and nonimmune cells such as epithelial cells that are in constant and close contact with invading microbes. This pulmonary perspective addresses our current understanding of the structure and function of NLR family members, highlighting advances and gaps in knowledge, with a specific focus on immune responses in the respiratory tract during bacterial infection. Further advances in exploring cellular and molecular responses to bacterial pathogens are critical to develop improved strategies to treat and prevent devastating infectious diseases of the lung.

Keywords: lung, bacterial infection, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain–like receptors, inflammasome

Bacterial Lung Infections

Despite sophisticated advances in pulmonary medicine, lower respiratory tract infections remain a significant cause of morbidity, mortality, and health care costs in many countries regardless of socioeconomic status. The main bacterial pathogens causing bacterial lung infection in humans are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, group A Streptococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella pneumophila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (1). In the United States, bacterial pneumonia is common, with an incidence of 4 million adult cases per year, resulting in 1.1 million hospitalizations and 50,000 deaths annually despite the use of antibiotics and supportive care measures (1). Although antibiotics are the rational treatment for pneumonias, antibiotic-resistant S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. aureus, and M. tuberculosis have been isolated from patients suffering from lower respiratory tract infections. Because of the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria, understanding innate immune response to bacterial infection is a priority to ultimately formulate therapeutic strategies to augment host immune mechanisms to combat microorganisms.

The initial phase of a bacterial lower respiratory tract infection is characterized by neutrophil-mediated inflammation. Although neutrophil recruitment aids in the removal of bacteria, it also induces bystander injury to the lung parenchyma. When severe, this injury may lead to a clinical condition termed acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. The relative contribution of hematopoietic cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, versus nonhematopoietic cells (epithelial cells and endothelial cells) to neutrophil accumulation into the lung is dependent on the stimulus, because both are exposed to inflammatory components. In prior studies, it has been proposed that myeloid cells in the lung produce multiple neutrophil chemoattractants, such as keratinocyte-derived chemokine and macrophage inflammatory protein-2, to target lung resident cells, including epithelial cells and fibroblasts, to cause cytokine and chemokine expression. Neutrophils clear bacteria by phagocytosis followed by killing via proteases and reactive oxygen species. Both the activation of sentinel cells and the phagocytosis and killing by neutrophils are critically dependent on the recognition of pathogens by the innate immune system (2). As an additional mechanism, during inflammation, polymorphonuclear cells release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which are composed of DNA and cytosolic antimicrobial agents. NETs have been shown to confine pathogens, including bacteria (3). However, the importance of NETs in host defense against respiratory bacterial pathogens has been largely unexplored.

The large respiratory epithelial surface encounters a multitude of inhaled pathogens with every breath, and the epithelium has evolved multiple mechanisms to prevent infection (4). First, the epithelium constitutes an impermeable barrier made of intercellular tight junctions (5). Second, mucociliary clearance achieves physical removal of pathogens (6). Third, epithelial cells secrete diverse antimicrobial peptides, including lactoferrin, defensins, and cathelicidins, as well as collectins, which exert direct antimicrobial activity and function as regulators of the innate and adaptive immune systems (7). Epithelial-derived oxidants also possess antimicrobial and proinflammatory effects (8). Fourth, epithelial cells (as well as other sentinel cells) express pattern recognition molecules (PRMs) that recognize microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) in their vicinity. Finally, epithelial-derived neutrophil chemoattractants, such as CXCL5 and lungkine, contribute to the immune response to bacterial pathogens (9, 10).

PRM signaling can result in the production of antibacterial molecules, stimulate autophagy, and/or regulate programmed cell death (11). The MAMP ligands for specific PRMs are highly conserved “non-self” molecular motifs of microbial origin; examples include LPS, peptidoglycan, flagellin, and CpG nucleotides (11). PRMs can also interact with another set of molecular motifs known as damage (or danger)-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are endogenous (“self”) molecules emanating from stressed (dying/infected/cancerous) cells. This pulmonary perspective focuses on the structure and function of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs) and their importance in orchestrating the innate immune response to bacterial lung infections.

The NLR Family

After the discovery of membrane-bound Toll-like receptors (TLRs), it became clear that additional sensors were crucial for microbial surveillance in the cytoplasm. NLRs are cytosolic proteins that respond to diverse ligands ranging from bacterial and viral components to particulate matter and crystals. Intracellular pathogens or bacteria equipped with transmembrane secretion systems provide cytosolic MAMPs that may interact with NLRs (12, 13). In addition, extracellular gram-negative bacteria may shed membrane “blebs” that can be transported to the cytosol via lipid rafts to initiate NLR-dependent responses (14). Although it is well established that NLRs can sense a wide array of ligands, the exact mechanisms for the transmembrane delivery of these ligands to the cytosol, and whether they directly bind NLRs, are in many instances not well understood.

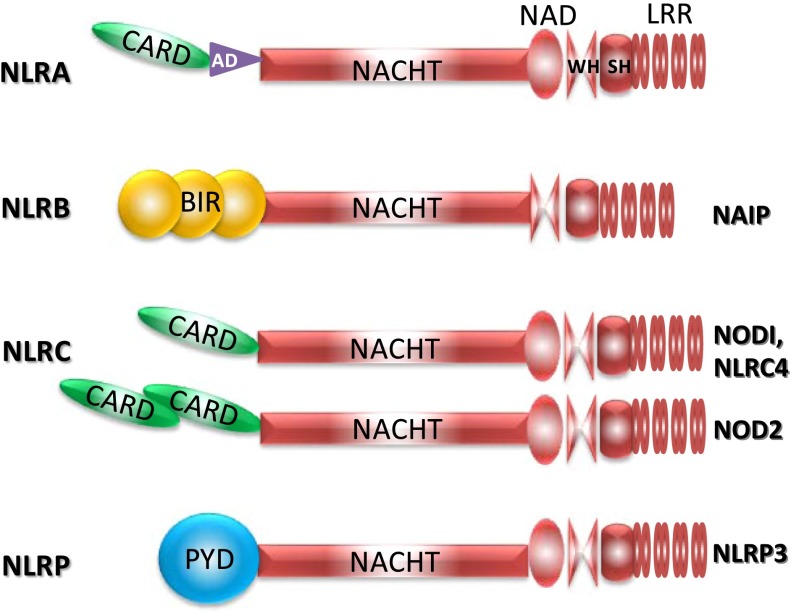

All NLR family members are characterized by a tripartite domain structure with a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain, a central NACHT (NAIP, CIIA, HET-E, TP1) NOD, and a variable N-terminal effector domain (15). NLRs are classified into four subfamilies based on the N-terminal effector domain they contain: NLRA members have transactivator activation domains (ADs); NLRBs have BIR (baculoviral inhibitor of apoptosis repeat) domains; NLRCs have CARD (caspase activation/recruitment domains), and NLRPs have PYD (pyrin domains) (16). Each domain of the NLR molecule has a unique function. The C-terminal LRR sensing domain recognizes a variety of cytosolic ligands. This is followed by oligomerization of NACHT domains leading to the formation of an N-terminal platform where diverse adaptor molecules and downstream effectors may bind (16). The variable molecular makeup at the N terminus ascribes a degree of structural heterogeneity that in part dictates the recruitment of adaptor molecules and the activation of downstream signaling pathways depending on the specificity of NLR and/or their ligands (Figure 1). The following sections highlight key structural differences among NLRs important in pulmonary inflammation and immunity.

Figure 1.

A schematic comparing molecular structures of various NOD (nucleotide-associated oligomerization domain)-like receptor (NLR) family members relevant to bacterial lung infection. All NLRs have a tripartite domain organization comprising a C-terminal LRR, middle NACHT, and a variable N-terminal domain. The variability of the N-terminal domains is the basis for the division of NLRs into distinct subgroups. AD = activation domain; BIR = baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis protein repeat; CARD = caspase recruitment domain; LRR = leucine-rich repeat; NACHT = NAIP, CIIA, HET-E, TP1; NAD = NACHT-associated domain; NAIP = NLR family apoptosis-inducing protein; PYD = pyrin domain; SH = superhelical domain; WH = winged helix domain.

NOD1 and NOD2

The cytosolic proteins NOD1 and NOD2 were the first NLRs discovered as pathogen sensors. Both NOD1 and NOD2 contain CARD domains at their N termini. Whereas NOD1 is expressed in a wide variety of cells and tissues, the expression of NOD2 is restricted to relatively few cell types including macrophages, dendritic cells, and lung epithelium (17). Principally described, bacterial ligands for NOD receptors are components of bacterial peptidoglycan. Specifically, m-DAP (l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-m-diaminopimelic acid) found in most gram-negative and some gram-positive bacteria binds NOD1 while the MDP (muramyl dipeptide) motif present in the peptidoglycans of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria binds NOD2 LRR (17). Peptidoglycan binding is followed by oligomerization of the central NACHT domains and recruitment of the cytosolic adaptor molecule receptor-interacting protein-2 (RIP2) at the N terminus by CARD–CARD interaction. RIP2 is then ubiquitinated, leading to the activation of downstream NF-κB signaling and up-regulation of genes involved in host defense and apoptosis (17).

Inflammasomes

On ligand recognition, some NLR proteins form distinct hetero-oligomeric structures known as inflammasomes. Inflammasomes are platforms for the recruitment of pro–caspase-1 zymogen by CARD–CARD interaction followed by its activation to caspase-1 by proteolytic cleavage. Caspase-1 protease in turn activates pro–IL-1β and pro–IL-18 to IL-1β and IL-18, respectively, inducing inflammation. Under certain conditions, caspase-1 can also mediate pyroptosis, which is a caspase-1–dependent form of inflammatory programmed cell death. The CARD in an inflammasome may belong to either a constituent NLR or to a CARD-containing adaptor protein, ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal CARD) (16). NLRC4 and NLRP3 are the two most extensively studied inflammasome-forming NLRs that orchestrate immune responses to an array of important human pulmonary pathogens.

NLRC4 and NAIPs

NLRC4 and NAIP (NLR family apoptosis-inducing protein) are two structurally dissimilar NLR proteins that together form the NLRC4 inflammasome. NAIPs exhibit tripartite protein structure with a C-terminal LRR, a central NACHT, and N-terminal BIR domains akin to other NLR family members (Figure 1). After activation, the central NACHT of NLRC4 proteins oligomerizes with NAIP, resulting in the formation of an inflammasome (18). NAIPs and NLRC4 functionally complement one another as inflammasome constituents, with NAIP-LRR acting as an MAMP sensor while NLRC4-CARD recruits and activates pro–caspase-1. The role of the BIR domains in the organization of inflammasomes, their downstream signaling, and their relevance to immune defense against bacterial pathogens remains to be elucidated, although it is proposed that all three BIR domains are necessary for MAMP-induced oligomerization of NLRC4 (19). Because NLRC4 is equipped with its own CARD domain, whether the ASC adaptor is necessary for NLRC4 inflammasome function is not fully established (18). The majority of in vitro studies assessing cytokine production via NLRC4 have been performed primarily in macrophages, and although NLRC4 expression has been documented in epithelial cells in other anatomic locations, its role in pulmonary epithelium is undefined (20).

When comparing experiments using murine models and human cell lines it is important to note that there are four NAIP paralogs in mice, namely, NAIP1, NAIP2, NAIP5, and NAIP6, whereas only one functional protein, hNAIP, has been detected in humans (21). The murine NAIP paralogs are proposed to be involved in differential ligand recognition. For example, NAIP5 LRR and NAIP6 LRR selectively recognize flagellin, NAIP2 LRR recognizes PrgJ (type III secretion system [T3SS] needle protein), and NAIP1 also recognizes T3SS needle protein (19, 22, 23). hNAIP and NAIP5 are both responsible for recognition of L. pneumophila flagellin and limiting growth of this bacterium within macrophages via assembly of the NLRC4 inflammasome (24). Interestingly, in human epithelial cells, hNAIP has been shown to inhibit L. pneumophila replication, despite the lack of NLRC4 expression in these cells, indicating the immune functions of NAIPs may extend beyond the NAIP/NLRC4 paradigm (24).

NLRP3

NLRP3 has been principally studied in human and murine macrophages; however, NLRP3 inflammasome constituents are also expressed in human and murine airway epithelial cells on bacterial challenge (25). The defining feature of NLRP3 is the N-terminal PYD that homotypically binds PYD of ASC. The NLRP3 inflammasome is also prototypical in its requirement for two distinct signals for activation. The preassembly “priming” signal comes from TLR activation that induces NLRP3 expression via NF-κB activation. Once the cytosolic amount of NLRP3 reaches a threshold, inflammasome assembly is initiated in response to a second signal originating from one or more NLRP3 ligands (26). The two-signal process may act as a cellular safeguard against hyperactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Although other inflammasomes may not depend on TLR signaling for synthesis of their constituent molecules, it should be noted that TLR signaling does contribute to increased cytosolic expression of pro–IL-1β, and production of mature IL-1β by other inflammasomes may be impacted by TLR activation (25).

NLRP3 ligands are a curiously heterogeneous group of compounds ranging from exogenous materials including bacterial MAMPs, ozone, asbestos, silicon, and particulate matter to endogenous alarmins such as uric acid from DNA damage, ATP, and mitochondrial contents (27–35). The ability of the NLRP3 inflammasome to respond to an array of structurally and chemically diverse signals points to convergence on a common subcellular event upstream of inflammasome assembly. The drop in the intracellular concentration of K+ (K+ efflux) has been shown to be a necessary and sufficient event that acts upstream of the ASC adaptor, resulting in assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome and activation of caspase-1 (36). K+ efflux is a common feature to the many cellular events such as membrane permeability or pore formation, lysosomal and mitochondrial damage, and reactive oxygen species production that are proposed to activate NLRP3 (36).

NLRs in Inflammation

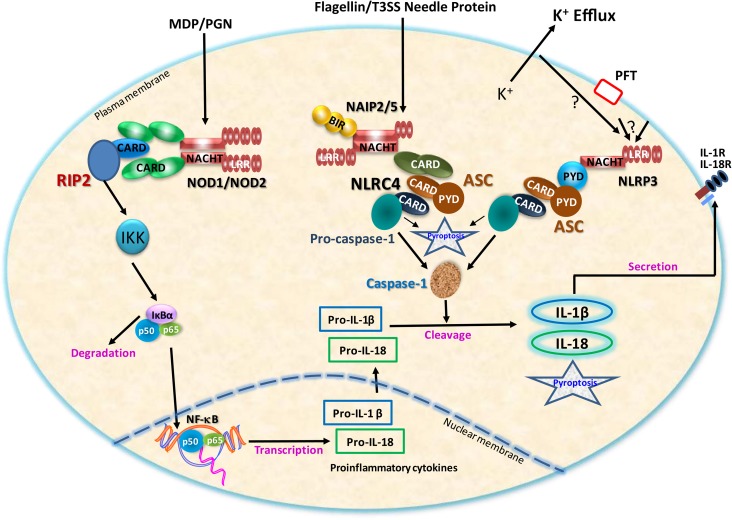

Most studies support a pivotal role for NLRs as PRMs that recognize bacterial pathogens and induce downstream molecular pathways to generate cytokines and chemokines that play important roles in the pathophysiology of bacterial infections (Figure 2). The NLRs and bacterial components or PRMs that are recognized by NLRs are listed in Table 1 regarding respiratory bacterial infection. Notably, in vivo correlates to assess leukocyte recruitment, bacterial clearance, or survival are either lacking or provide apparently discrepant results. For example, NOD1, NOD2, and/or RIP2 gene–deficient mice infected with C. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and L. pneumophila demonstrated reduced levels of pulmonary cytokines and chemokines and impaired neutrophil recruitment to the lungs (12, 37–39). Interestingly, C. pneumoniae–infected NOD1/2 and RIP2 gene–deficient mice had decreased bacterial clearance (38), S. aureus–infected wild-type and NOD2 gene–deficient mice showed similar pulmonary CFUs (37), while the pulmonary bacterial burden in NOD1/2 and RIP2 gene–deficient mice infected with L. pneumophila were enhanced (12, 39). In the human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293, activation of NF-κB after invasion by S. pneumoniae was dependent on NOD2 (40). Experiments using HEK293 and the A549 human respiratory epithelial cell line showed that peptidoglycan from the gram-negative pathogen H. influenzae stimulated NF-κB and production of IL-8 in a NOD1-dependent manner when cells were coincubated with an S. pneumoniae strain expressing the pore-forming toxin pneumolysin (41). The synergy between H. influenzae and pneumolysin of S. pneumoniae is an interesting model of NOD1 activation that may be relevant in cases of polymicrobial colonization of the respiratory tract (41). In response to Mycobacterium species, macrophages from NOD2 gene–deficient mice produced significantly less tumor necrosis factor-α as compared with wild-type control macrophages. In addition, human mononuclear cells harvested from patients homozygous for a frameshift loss of function mutation in NOD2 (3020insC) synthesized 65–80% less tumor necrosis factor-α than did homozygous wild-type mononuclear cells when challenged with M. tuberculosis (42).

Figure 2.

A schematic representation of NOD (nucleotide-associated oligomerization domain)-like receptor (NLR) signaling pathways. Cytosolic NLRs recognize bacterial components (microbial-associated molecular patterns) and activate downstream proinflammatory signaling cascades in the respiratory tract, resulting in host defense and/or excessive inflammation. ASC = apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal CARD; BIR = baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis protein repeat; CARD = caspase recruitment domain; IKK = I-κB kinase; LRR = leucine-rich repeat; MDP = muramyl dipeptide; NACHT = NAIP, CIIA, HET-E, TP1; NAIP = NLR family apoptosis-inducing protein; PFT = pore-forming toxin; PGN = peptidoglycan; PYD = pyrin domain; RIP2 = receptor-interacting protein-2; T3SS = type III secretion system.

Table 1.

Role of Nucleotide-Binding Oligomerization Domain–like Receptors in Respiratory Bacterial Infection

| Bacteria | MAMP | NLR | Phenotype* | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bordetella pertussis | CyaA | Unknown | Snd Nnd BB↑ | 61 |

| Inflammasome | BDnd (IL-R1–/– mice) | |||

| Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) pneumoniae | Unknown | Unknown | S↓ Nnd BB↑ BDnd | 62 |

| Inflammasome | (caspase-1–/– mice) | |||

| PGN | NOD1/NOD2 | S↓ N↑ BB↑ BDnd | 38 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Unknown | NLRC4 | S↓ N↓ BB↑ BD↑ | 49 |

| Unknown | NLRP3 | S↓ N↓ BBnd BDnd | 45 | |

| Legionella pneumophila | Flagellin | NLRC4 | Snd Nns BB↑ BDnd | 63 |

| PGN | NOD1/NOD2 | S↓ N↓ BB↑ BDnd | 12, 39 | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | mAGP | NOD2 | Sns Nns BBns BDnd | 64 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Flagellin/ExoUT3SS | NLRC4 | Sns Nnd BB↑ BD↑ | 46, 65, 66 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | MDP | NOD2 | Sns N↓ BBns BDnd | 37 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Pneumolysin | NLRP3 | S↓ Nns BBns BDns | 28 |

Definition of abbreviations: CyaA = adenylate cyclase toxin; ExoUT3SS = exoenzyme U type III secretion system; IL-1R = IL-1 receptor; mAGP = mycoarabinogalactan; MAMP = microbial-associated molecular pattern; MDP = muramyl dipeptide; NLR = NOD-like receptor; NOD = nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain; PGN = peptidoglycan.

Phenotype represents outcomes in gene-deficient mice after infection. ↓ = decreased; ↑ = increased; BB = bacterial burden in the lungs; BD = bacterial dissemination; N = neutrophil influx; nd = not determined; ns = no significant difference in gene-deficient mice compared with wild-type mice; S = survival.

Pneumolysin and other bacterial pore-forming toxins, such as streptolysin O (Streptococcus pyogenes) and α-hemolysin (S. aureus), also induce NLRP3 inflammasomes (27–29, 43, 44). Pneumolysin-expressing strains of S. pneumoniae stimulate IL-1β production via NLRP3 in both human and murine macrophages. In addition, NLRP3 activation is protective for mice infected with pneumolysin-expressing S. pneumoniae (28). For S. pneumoniae, virulence factor polymorphism may be the means by which certain clinically relevant strains lacking pneumolysin expression evade this important detection system, and are able to establish invasive infections (28).

P. aeruginosa stimulates NLRC4 (also known as IPAF) activation via a T3SS used to inject various virulence factors into the host cytosol. The P. aeruginosa strain expressing the exoenzyme U (ExoU) phospholipase was able to suppress caspase-1–mediated cytokine production via NLRC4 (46). Although less than one-third of P. aeruginosa clinical isolates express ExoU, these strains are associated with more severe disease; however, this may relate to functions of the ExoU virulence factor that are independent of NLRC4 (46). In addition to its T3SS, P. aeruginosa flagellin provides another means of detection via NLRC4. Interestingly, it appears that recognition of P. aeruginosa via NLRC4 may depend not only on expression of a T3SS or flagellin, but also on motility, because caspase-1 activation and IL-1β production were reduced in peritoneal macrophages and bone marrow–derived dendritic cells exposed to nonmotile P. aeruginosa (47). This finding may have broad implications because loss of bacterial motility is described in a number of diseases and is thought to favor persistence in the host. As an example, the temporal loss of P. aeruginosa motility has been described during chronic infections in patients with cystic fibrosis (48). Interestingly, K. pneumoniae, which expresses neither flagellin nor T3SS, also activates NLRC4, indicating that NLRC4 must recognize other ligands that remain to be characterized. Furthermore, the exact molecular pathway leading to the activation of NLRC4 by extracellular pathogens such as K. pneumoniae has not been delineated (49). In addition, a slow-growing mycobacterial agent, Mycobacterium kansasii, activates NLRP3 within human macrophages, and generation of IL-1β by NLRP3 was shown to restrict intracellular growth of M. kansasii (50).

NLRs in Pyroptosis

Pyroptosis is a caspase-1–dependent programmed cell death pathway that is downstream of inflammasome activation. Activated caspase-1 forms small cation-permeable pores in the cell membrane, allowing influx of calcium as well as cellular swelling and fluid imbalance, all of which ultimately contribute to cell death (51). However, inflammasome activation may not always result in pyroptosis. For example, human and murine macrophages incubated with K. pneumoniae generate IL-1β via NLRC4, although pyroptosis has not been observed in murine macrophages and neutrophils isolated from the lungs of K. pneumoniae–infected mice (49). In contrast, NLRC4-mediated pyroptosis occurs during infections with L. pneumophila and P. aeruginosa (46, 52). In experimental L. pneumophila infection pyroptosis appears protective, as caspase-1–mediated clearance of L. pneumophila in vivo was independent of IL-1β and IL-18 (52). In this model, cell lysis presumably liberates infectious agents into the extracellular space, where they may be more readily killed. However, as pyroptosis is inherently inflammatory, it may also contribute to morbidity in other models, as strong evidence for a protective role does not currently exist for all infectious inducers of pyroptosis.

How exactly cells modulate pyroptosis has largely remained elusive. In the case of NLRC4 differential expression of the adaptor protein ASC has some effect on pyroptosis, but plays a more pivotal role in cytokine production. NLRC4 inflammasomes can be formed with or without ASC, and activation of both structures is required for maximal production of IL-1β and IL-18 in macrophages infected with L. pneumophila (53). In contrast, NLRC4-NAIP–mediated pyroptosis is independent of ASC activity in this L. pneumophila model, and in ASC-deficient cells, pyroptosis is slightly enhanced (53). Similarly, ASC is required for maximal production of IL-1β via NLRC4 but is dispensable for pyroptosis in a P. aeruginosa infection model (46).

Evidence suggests pyroptosis may be controlled in part by autophagy. Autophagy is a programmed cellular pathway by which cells engulf portions of their own cytoplasm, membrane, and organelles. This process may function in nutrient recycling, as well as degrading toxic metabolites such as reactive oxygen species during times of cellular stress (51). The various cascades that connect NLRs to autophagy during bacterial infection give rise to a complex network. In murine macrophages infected with L. pneumophila NAIP5 and NLRC4 stimulated autophagosome turnover. In addition, stimulation of autophagy appeared to inhibit pyroptosis, as caspase-1–dependent cell death occurred more frequently in cells when autophagy was blocked pharmacologically (54). These studies demonstrate that NLR activation increases autophagy, and that autophagy may be an important negative regulator of inflammasomes. Indeed, autophagy has been shown to deplete cytosolic IL-1β and inflammasome constituents as well as suppress maturation of caspase-1 (55, 56). The prevailing paradigm from studies of autophagy and pyroptosis appears to be that autophagy decreases caspase-1 activation, but that increased levels of caspase-1 can also limit autophagy (51). Thus, if autophagy is effective in limiting caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis may be avoided; however, if caspase-1 prevails, inflammatory cell death occurs (51).

NLRs in Multifactorial Disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is primarily a cigarette smoke (CS)-related multifactorial disease in which chronic exposure to an inhaled irritant leads to airway remodeling, reduced mucociliary clearance, and destruction of the pulmonary parenchyma (57). Chronic ongoing inflammation contributes to disease progression and can be exacerbated by development of bacterial lung infections, which is favored because of compromised innate immune defenses.

CS-induced tissue damage can lead to formation of the NLRP3 ligands uric acid and calcium pyrophosphate, and in a model of acute CS inhalation, caspase-1 (now caspase-1/11) gene–deficient mice had reduced pulmonary inflammation, indicating inflammasome activation in response to CS challenge (57, 58). In a more recent publication, however, the degree of pulmonary inflammation after subacute CS exposure was independent of NLRP3 and caspase-1, but dependent on the IL-1 receptor type I. Both IL-1α and IL-1β were elevated in lung tissue and sputum samples from patients with COPD in this same study, indicating a potentially underappreciated role for IL-1α in COPD-induced inflammation (57). The discrepancies between these studies may in part reflect differences in time course, as CS may induce inflammation by alternative mechanisms during the course of disease. In addition, these studies do not account for innate immune stimulation by bacterial agents known to exacerbate COPD.

Nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHi) is the most important bacterial species responsible for acute exacerbations of COPD (25). Stimulation with NTHi induced NLRP3 inflammasome up-regulation in human and murine macrophages and human bronchial epithelial cells (25). Moreover, stimulation with NTHi led to caspase-1 induction and production of IL-1β and IL-18 in human lung tissue, indicating that NLRP3 may be an active player in acute inflammation during bacterial infections in patients with COPD (25).

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is another multifactorial disease caused by environmental stressors and bacterial infection in severely injured patients. Although the role of NLRs in VAP has not been explored, studies have shown the role of inflammasomes in ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). Although VILI is not infectious in nature, we reviewed some articles in this area because (1) VILI is an important pulmonary disease; (2) inflammation is associated with VILI; and (3) the findings from VILI may help our understanding of the mechanisms in the pathogenesis of VAP. Mechanical ventilation can contribute to the injury of both healthy and previously injured lungs, that is, VILI. Even when lower tidal volumes are used to reduce barotrauma, in lungs with existing injury some areas may be collapsed, while others are intrinsically prone to hyperinflation and injury (59). VILI causes release from dying cells of DAMPs including uric acid, ATP, and hyaluronan, all known inducers of the NLRP3 inflammasome (59). In this regard, mechanical ventilation up-regulated NLRP3 and ASC mRNA, caspase-1, and IL-1β in the lungs of mice and also increased NLRP3 expression in human and murine alveolar macrophages (59). VILI was reduced in the lungs of NLRP3 and ASC gene–deficient mice and in wild-type mice treated with an IL-1 receptor antagonist (59). Although these data strongly support a role for NLRP3 in VILI, the interplay between VILI, VAP, and NLRs is less clear. Although many of the pulmonary pathogens commonly isolated from VAP are known inducers of NLR activation, the combined impact of ventilator support and experimental infection needs to be explored in future studies.

Conclusions

Bacterial lung diseases are an important public health concern. Innate immune response to bacteria in the lung is a double-edged sword: an impaired response can result in life-threatening infection whereas an uncontrolled response can lead to life-threatening inflammatory disease. Although the importance of NLRs has emerged, much still remains to be learned, as new NLR family members, their ligands, and downstream signaling cascades are constantly being discovered. Molecular studies investigating cross-talk between TLRs and NLRs, and spatial association of NLR proteins with intracellular adaptors and autophagy machinery are needed for a more complete understanding of how antibacterial innate immune responses are integrated between immune sensors, and how these sensors bridge innate and adaptive responses. Understanding the connection between NLRs and autophagy is an exciting field in biology with many unanswered questions related to the molecular mechanisms that warrant future studies. The translational relevance of NLR research is most evident in the novel therapeutic targets it has identified. Caspase-1, IL-1β, and IL-1 receptor antagonists, and the uric acid inhibitors, uricase and allopurinol, have been tested in animal models with varied success in combating deleterious NLR-mediated inflammation (57–60). The next logical step for NLR research may incorporate environmental stressors (i.e., CS, ventilator support), with bacterial challenge, thus enhancing our understanding of NLR-mediated antibacterial immunity within a framework relevant to human disease. Moreover, the future challenge will be to apply our current understanding of NLRs to reducing excessive inflammation while augmenting host defense during respiratory bacterial infection.

Footnotes

Supported by a Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI) Young Clinical Scientist Award (FAMRI YCSA_092417) to R.K., and by Clinical Innovator Award CIA_113043 and National Institutes of Health Grant R01-HL 091958 to S.J.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201311-2103PP on April 7, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Jr, Musher DM, Niederman MS, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–S72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizgerd JP. Acute lower respiratory tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:716–727. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitsett JA. Intrinsic and innate defenses in the lung: intersection of pathways regulating lung morphogenesis, host defense, and repair. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:565–569. doi: 10.1172/JCI15209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallstrand TS, Hackett TL, Altemeier WA, Matute-Bello G, Hansbro PM, Knight DA. Airway epithelial regulation of pulmonary immune homeostasis and inflammation. Clin Immunol. 2014;151:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vareille M, Kieninger E, Edwards MR, Regamey N. The airway epithelium: soldier in the fight against respiratory viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:210–229. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00014-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grubor B, Meyerholz DK, Ackermann MR. Collectins and cationic antimicrobial peptides of the respiratory epithelia. Vet Pathol. 2006;43:595–612. doi: 10.1354/vp.43-5-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu W, Zheng S, Dweik RA, Erzurum SC. Role of epithelial nitric oxide in airway viral infection. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hippenstiel S, Opitz B, Schmeck B, Suttorp N. Lung epithelium as a sentinel and effector system in pneumonia–molecular mechanisms of pathogen recognition and signal transduction. Respir Res. 2006;7:97. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mogensen TH. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:240–273. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00046-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frutuoso MS, Hori JI, Pereira MS, Junior DS, Sonego F, Kobayashi KS, Flavell RA, Cunha FQ, Zamboni DS. The pattern recognition receptors Nod1 and Nod2 account for neutrophil recruitment to the lungs of mice infected with Legionella pneumophila. Microbes Infect. 2010;12:819–827. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miao EA, Warren SE. Innate immune detection of bacterial virulence factors via the NLRC4 inflammasome. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30:502–506. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9386-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaparakis M, Turnbull L, Carneiro L, Firth S, Coleman HA, Parkington HC, Le Bourhis L, Karrar A, Viala J, Mak J, et al. Bacterial membrane vesicles deliver peptidoglycan to Nod1 in epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:372–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koonin EV, Aravind L. The NACHT family—a new group of predicted NTPases implicated in apoptosis and MHC transcription activation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:223–224. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01577-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franchi L, Warner N, Viani K, Nunez G. Function of Nod-like receptors in microbial recognition and host defense. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:106–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Correa RG, Milutinovic S, Reed JC. Roles of NOD1 (NLRC1) and NOD2 (NLRC2) in innate immunity and inflammatory diseases. Biosci Rep. 2012;32:597–608. doi: 10.1042/BSR20120055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kofoed EM, Vance RE. NAIPs: building an innate immune barrier against bacterial pathogens. NAIPs function as sensors that initiate innate immunity by detection of bacterial proteins in the host cell cytosol. Bioessays. 2012;34:589–598. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kofoed EM, Vance RE. Innate immune recognition of bacterial ligands by NAIPs determines inflammasome specificity. Nature. 2011;477:592–595. doi: 10.1038/nature10394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu B, Elinav E, Huber S, Booth CJ, Strowig T, Jin C, Eisenbarth SC, Flavell RA. Inflammation-induced tumorigenesis in the colon is regulated by caspase-1 and NLRC4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21635–21640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016814108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endrizzi MG, Hadinoto V, Growney JD, Miller W, Dietrich WF. Genomic sequence analysis of the mouse Naip gene array. Genome Res. 2000;10:1095–1102. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.8.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Y, Yang J, Shi J, Gong YN, Lu Q, Xu H, Liu L, Shao F. The NLRC4 inflammasome receptors for bacterial flagellin and type III secretion apparatus. Nature. 2011;477:596–600. doi: 10.1038/nature10510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rayamajhi M, Zak DE, Chavarria-Smith J, Vance RE, Miao EA. Cutting edge: mouse NAIP1 detects the type III secretion system needle protein. J Immunol. 2013;191:3986–3989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinzing M, Eitel J, Lippmann J, Hocke AC, Zahlten J, Slevogt H, N’Guessan PD, Gunther S, Schmeck B, Hippenstiel S, et al. NAIP and Ipaf control Legionella pneumophila replication in human cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:6808–6815. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotta detto Loria J, Rohmann K, Droemann D, Kujath P, Rupp J, Goldmann T, Dalhoff K. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae infection upregulates the NLRP3 inflammasome and leads to caspase-1–dependent secretion of interleukin-1β—a possible pathway of exacerbations in COPD. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin C, Flavell RA. Molecular mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30:628–631. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harder J, Franchi L, Munoz-Planillo R, Park JH, Reimer T, Nunez G. Activation of the nlrp3 inflammasome by Streptococcus pyogenes requires streptolysin O and NF-κB activation but proceeds independently of TLR signaling and P2X7 receptor. J Immunol. 2009;183:5823–5829. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witzenrath M, Pache F, Lorenz D, Koppe U, Gutbier B, Tabeling C, Reppe K, Meixenberger K, Dorhoi A, Ma J, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome is differentially activated by pneumolysin variants and contributes to host defense in pneumococcal pneumonia. J Immunol. 2011;187:434–440. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iyer SS, Pulskens WP, Sadler JJ, Butter LM, Teske GJ, Ulland TK, Eisenbarth SC, Florquin S, Flavell RA, Leemans JC, et al. Necrotic cells trigger a sterile inflammatory response through the NLRP3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20388–20393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908698106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimada K, Crother TR, Karlin J, Dagvadorj J, Chiba N, Chen S, Ramanujan VK, Wolf AJ, Vergnes L, Ojcius DM, et al. Oxidized mitochondrial DNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome during apoptosis. Immunity. 2012;36:401–414. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shenoy AR, Wellington DA, Kumar P, Kassa H, Booth CJ, Cresswell P, MacMicking JD. GBP5 promotes NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and immunity in mammals. Science. 2012;336:481–485. doi: 10.1126/science.1217141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng F, Li Z, Potts-Kant EN, Wu Y, Foster WM, Williams KL, Hollingsworth JW. Hyaluronan activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome contributes to the development of airway hyperresponsiveness. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:1692–1698. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J. Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science. 2008;320:674–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nunez G, Schnurr M, et al. Nlrp3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, Mayor A, Martinon F, Tschopp J. Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1583–1589. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martinez-Colon G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Nunez G. K+ efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity. 2013;38:1142–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kapetanovic R, Jouvion G, Fitting C, Parlato M, Blanchet C, Huerre M, Cavaillon JM, Adib-Conquy M. Contribution of NOD2 to lung inflammation during Staphylococcus aureus–induced pneumonia. Microbes Infect. 2010;12:759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimada K, Chen S, Dempsey PW, Sorrentino R, Alsabeh R, Slepenkin AV, Peterson E, Doherty TM, Underhill D, Crother TR, et al. The NOD/RIP2 pathway is essential for host defenses against Chlamydophila pneumoniae lung infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000379. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berrington WR, Iyer R, Wells RD, Smith KD, Skerrett SJ, Hawn TR. NOD1 and NOD2 regulation of pulmonary innate immunity to Legionella pneumophila. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:3519–3527. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Opitz B, Puschel A, Schmeck B, Hocke AC, Rosseau S, Hammerschmidt S, Schumann RR, Suttorp N, Hippenstiel S. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain proteins are innate immune receptors for internalized Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36426–36432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ratner AJ, Aguilar JL, Shchepetov M, Lysenko ES, Weiser JN. Nod1 mediates cytoplasmic sensing of combinations of extracellular bacteria. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1343–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferwerda G, Girardin SE, Kullberg BJ, Le Bourhis L, de Jong DJ, Langenberg DM, van Crevel R, Adema GJ, Ottenhoff TH, Van der Meer JW, et al. NOD2 and Toll-like receptors are nonredundant recognition systems of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:279–285. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Munoz-Planillo R, Franchi L, Miller LS, Nunez G. A critical role for hemolysins and bacterial lipoproteins in Staphylococcus aureus–induced activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. J Immunol. 2009;183:3942–3948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Craven RR, Gao X, Allen IC, Gris D, Bubeck Wardenburg J, McElvania-Tekippe E, Ting JP, Duncan JA. Staphylococcus aureus α-hemolysin activates the NLRP3-inflammasome in human and mouse monocytic cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willingham SB, Allen IC, Bergstralh DT, Brickey WJ, Huang MT, Taxman DJ, Duncan JA, Ting JP. NLRP3 (NALP3, cryopyrin) facilitates in vivo caspase-1 activation, necrosis, and HMGB1 release via inflammasome-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol. 2009;183:2008–2015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutterwala FS, Mijares LA, Li L, Ogura Y, Kazmierczak BI, Flavell RA. Immune recognition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mediated by the IPAF/NLRC4 inflammasome. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3235–3245. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patankar YR, Lovewell RR, Poynter ME, Jyot J, Kazmierczak BI, Berwin B. Flagellar motility is a key determinant of the magnitude of the inflammasome response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 2013;81:2043–2052. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00054-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luzar MA, Thomassen MJ, Montie TC. Flagella and motility alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from patients with cystic fibrosis: relationship to patient clinical condition. Infect Immun. 1985;50:577–582. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.2.577-582.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cai S, Batra S, Wakamatsu N, Pacher P, Jeyaseelan S. NLRC4 inflammasome–mediated production of IL-1β modulates mucosal immunity in the lung against gram-negative bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2012;188:5623–5635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen CC, Tsai SH, Lu CC, Hu ST, Wu TS, Huang TT, Said-Sadier N, Ojcius DM, Lai HC. Activation of an NLRP3 inflammasome restricts Mycobacterium kansasii infection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LaRock CN, Cookson BT. Burning down the house: cellular actions during pyroptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003793. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miao EA, Leaf IA, Treuting PM, Mao DP, Dors M, Sarkar A, Warren SE, Wewers MD, Aderem A. Caspase-1–induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1136–1142. doi: 10.1038/ni.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Case CL, Shin S, Roy CR. Asc and Ipaf inflammasomes direct distinct pathways for caspase-1 activation in response to Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1981–1991. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01382-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amer AO, Swanson MS. Autophagy is an immediate macrophage response to Legionella pneumophila. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:765–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris J, Hartman M, Roche C, Zeng SG, O’Shea A, Sharp FA, Lambe EM, Creagh EM, Golenbock DT, Tschopp J, et al. Autophagy controls IL-1β secretion by targeting pro–IL-1β for degradation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9587–9597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi CS, Shenderov K, Huang NN, Kabat J, Abu-Asab M, Fitzgerald KA, Sher A, Kehrl JH. Activation of autophagy by inflammatory signals limits IL-1β production by targeting ubiquitinated inflammasomes for destruction. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pauwels NS, Bracke KR, Dupont LL, Van Pottelberge GR, Provoost S, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P, Lambrecht BN, Joos GF, Brusselle GG. Role of IL-1α and the Nlrp3/caspase-1/IL-1β axis in cigarette smoke–induced pulmonary inflammation and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1019–1028. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00158110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Churg A, Zhou S, Wang X, Wang R, Wright JL. The role of interleukin-1β in murine cigarette smoke–induced emphysema and small airway remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:482–490. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0038OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuipers MT, Aslami H, Janczy JR, van der Sluijs KF, Vlaar AP, Wolthuis EK, Choi G, Roelofs JJ, Flavell RA, Sutterwala FS, et al. Ventilator-induced lung injury is mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1104–1115. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182518bc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuipers MT, Aslami H, Vlaar AP, Juffermans NP, Tuip-de Boer AM, Hegeman MA, Jongsma G, Roelofs JJ, van der Poll T, Schultz MJ, et al. Pre-treatment with allopurinol or uricase attenuates barrier dysfunction but not inflammation during murine ventilator-induced lung injury. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dunne A, Ross PJ, Pospisilova E, Masin J, Meaney A, Sutton CE, Iwakura Y, Tschopp J, Sebo P, Mills KH. Inflammasome activation by adenylate cyclase toxin directs Th17 responses and protection against Bordetella pertussis. J Immunol. 2010;185:1711–1719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimada K, Crother TR, Karlin J, Chen S, Chiba N, Ramanujan VK, Vergnes L, Ojcius DM, Arditi M. Caspase-1 dependent IL-1β secretion is critical for host defense in a mouse model of Chlamydia pneumoniae lung infection. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berrington WR, Smith KD, Skerrett SJ, Hawn TR. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing-like receptor family, caspase recruitment domain (CARD) containing 4 (NLRC4) regulates intrapulmonary replication of aerosolized Legionella pneumophila. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:371. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gandotra S, Jang S, Murray PJ, Salgame P, Ehrt S. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain protein 2–deficient mice control infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5127–5134. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00458-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miao EA, Ernst RK, Dors M, Mao DP, Aderem A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa activates caspase 1 through Ipaf. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2562–2567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712183105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Franchi L, Stoolman J, Kanneganti TD, Verma A, Ramphal R, Nunez G. Critical role for Ipaf in Pseudomonas aeruginosa–induced caspase-1 activation. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:3030–3039. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]